Abstract

This study delves into the relationship between the subject and things by regaining the anthropological and cultural values that have become embedded in objects already theoretically investigated by other disciplines (philosophy, literature, history of art, cinema) but here presented together with the works of designers that from the 19th to the 21st century managed to give a voice to things. This presentation springs from multi-annual research undertaken by the author at the universities of Bologna and Parma. After selecting twenty-four everyday objects (like mirror, ring, chair, table, telephone, suitcase, door), the research carried out for each one an analysis of its symbolic and cultural values and required students to create a graphic concept map to be intertwined with other maps, therefore with other objects, in more complex structures. This essay focuses on one object, the mirror, in order to explain thoroughly the survey method. Delving into the cultural values of objects gives the material landscape that surrounds us a critical perspective, which is essential to the comprehension and the project.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 “Psychological Reaction” Objects

“The transformation of objects into things (which also includes them becoming symbols, as occurs with an arrow or a cross) also presupposes a developed ability to reawaken memories, re-create contexts, be told stories and practice both «closed nostalgia» that isolates itself in the regret of what has been lost and «open nostalgia» able to positively cope with grief and loss” [1]. The closed nostalgia Remo Bodei writes about arises when objects behave as a Proustian madeleine enabling memories to resurface and the Freudian repressed world to reveal itself. Differently, open nostalgia appears when “things are not subordinated to the implacable desire to go back to an irretrievable past anymore […] but they have become vehicles of a journey to discover a past charged with a possible future.” [1]. According to this definition, things become essential tools know the past and imagine, invent, build the future.

The research focuses on the relationship between the subject and things regaining anthropological and cultural values that have become embedded in objects already theoretically investigated by other disciplines (philosophy, literature, history of art, cinema) but here presented together with the works of designers that from the 19th to the 21st century managed to give a voice to things. The originality of the work lies in recognizing consolidated functional categories, here systematized, which are associated with other values to be able to interpret the objects of the current industrial design everyday reality, too often observed from the perspective of function, shape and attractiveness, in the light of these considerations. The result is a more conscious way to look at objects considering their cultural values, and not just functional or formal values.

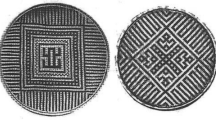

This presentation springs from multiannual research conducted by the author at the universities of Bologna and Parma. After selecting twenty-four everyday objects (like mirror, ring, chair, table, telephone, suitcase, door), the research carried out for each one of them an analysis of its symbolic and cultural values collected during a series of seminars. Each student was asked to create a graphic concept map for each object (Fig. 1) and then to design a thematic project that could be intertwined with the other maps, therefore with the other objects, in more complex structures. The second phase was implemented together with Professors Stefano Ascari and Andrea Borsari of the integrated course of Design Aesthetics. In this second phase, students had to collect different objects connected to a common theme and create their own personal collection.

This working method explains the anthropological contents of an object and significantly varies from one student to the other. Some students created the map in chronologic order as a timeline highlighting the mutations of the object through the centuries; others created the map as a flow chart or with a hierarchical structure assigning different values to different points. This type of research connects theoretical contents with creative activity and is a preliminary method to the creation of the design object.

The nexus of data and anthropological and psychological considerations was achieved on purpose in order to make tangible the complexity of references intrinsic to the object. Systematization is not meant to be exhaustive, but sufficiently representative to be a support to the analysis and the project about everyday objects.

2 Functions and Meanings

In Freud’s and Lacan’s reflections, the mirror takes on the specific function of amplifying the sensorial potentialities of the viewer and becomes an almost active tool, or maybe the reification of the Delphic oracle “know thyself”. In his intense essay On mirrors written in 1985, Umberto Eco questions the semiosic nature of reflected images and eventually writes that “The mirror in the world of signs becomes a ghost of itself, caricature, mockery, memory.” [2]. According to Umberto Eco, the catoptric universe of the mirror is the threshold of the tangible or semiosic one and the two of them do not have any connection. Therefore, the leap Through the mirror made by Lewis Carrol’s Alice holds the symbolic value of a passage to a virtual and oneiric world. And in the dimension of dream, or better of hallucination lies Borges’ Library of Babel where he writes: “… I prefer to dream that burnished surfaces are a figuration and promise of the infinite” [3]. These are just a few examples of the numerous mirrors studding literature and the collective imagination: Narcissus, Snow White, the numerous Venuses intent on gazing at their earthly vanities and the Picture of Dorian Gray, reflection of his dissolute owner’s black soul.

2.1 Recognise and Discover Oneself

Before the advent of the mirror as an object, sheets of water used to reflect images. Ovid (subject) freezes this ritual in the myth of Narcissus, the handsome and cruel young man who disdains with tenacious arrogance anyone falling in love with him [4]. As divine punishment, he becomes infatuated with his image reflected in a sheet of water and dies of consumption by the lake. Caravaggio portraits Narcissus while looking at his reflection in the spring water with desire. The arching arms generate the composition geometry of the painting and complete, with their double, a circular embrace representing the research of an impossible completion, the physical contact with his own reflection. Ovid refers to a closed and shaded environment, a perfect Caravaggesque backdrop from which the figure and the deceit of his double can emerge.

The mirror is the allegory of the exact vision and is used to know oneself. It is not a coincidence that the verb “reflect” has a double meaning: “to throw back an image” and “meditate, think deeply about something”. Playing with words, Jean Cocteau states «Mirrors should reflect a little before throwing back images» [5].

The Mirror Stage is one of the first contributions Jacques Lacan [6] gave to Freudian psychoanalysis in 1936 and then in a conference in 1949. From the age of six months, when the infant is still unable to talk and walk, he produces before the adult’s eyes the “startling spectacle of the infant in front of the mirror” recognizing his own image. The mirror stage is “an identification in the full sense that analysis gives to the term: namely, the transformation that takes place in the subject when he assumes an image”. The natural fragmentation of the body of the subject (Je) in the vision of the infant is put back together for the first time in the mirror which show a unified image (Moi). The split between these two images on both sides of the mirror accompanies the subject throughout all his life.

In the traumatic transition from childhood to adolescence the mirror becomes a tool to control the continuous changes the body undergoes, especially the female body. The Girl at mirror by Norman Rockwell looks at herself disappointed comparing her own image with the image of the movie star in the magazine on her lap. At her feet, there are a comb, a brush and make-up, tools of a woman’s transformation that she has maybe stolen from her mother. The mirror as a tool to compare oneself with the aesthetic models imposed by the society of image is an extremely topical issue, especially when one thinks of the endemic use of the digital mirror, the selfie, among teenagers. Rockwell’s mirror is leaning against a chair and this dressing table feels like improvised in an unused space, maybe an attic or a storage closet, an “other place”, a heterotopia where the transition to adulthood can take place away from the world. A doll cast aside in a corner represents the end of childhood (Fig. 2).

The song Silvia by Vasco Rossi deals with the same topic. It is a ballad about the discovery of one’s body and sexuality (see Lacan) in front of the mirror.

“Silvia si veste davanti allo specchio E sulle labbra un po’ di rossetto Andiamoci piano però con il trucco Se no la mamma brontolerà Silvia, fai presto che sono le otto Se non ti muovi, fai tardi lo stesso E poi la smetti con tutto quel trucco Che non sta bene, te l'ho già detto Silvia non sente oppure fa finta Guarda lo specchio poco convinta Mentre una mano si ferma sul seno È ancora piccolo, ma crescerà Silvia ora corre oltre lo specchio Dimenticando che sono le otto E trova mille fantasie Che non la lasciano più andar via” | “Silvia gets dressed in front of the mirror And on the lips a bit of lipstick But take it easy with make-up Otherwise, mum will grumble Silvia, hurry up it is 8 o’clock If you don’t hurry, you’ll be late anyway And stop it with all that make-up It does not suit you I already told you that Silvia cannot hear or pretends not to She looks at the mirror insecure While a hand stops on her breast It is still small, but it will grow Silvia now runs beyond the mirror Forgetting it is already 8 o’clock And finds a thousand fantasies That won’t let her go”. [7] |

There is an object that perfectly depicts this potential of the mirror connected to the discovery of sexuality and changes in one’s body and to the comparison with dominant aesthetic models. It is Milo, designed by Carlo Mollino in 1937 and today produced by Zanotta. The mirror portrays the silhouette of the renowned Venus de Milo displayed at the Louvre Museum in Paris made in crystal with stainless steel latch for the attachment to the wall. The reflected image in this mirror inevitably compares itself with the silhouette of the goddess of beauty and love, a timeless model that is immutable to trends. The statue is already deprived of arms, yet Mollino adds further mutilations to define the shape of the mirror, reducing it to a torso. What remains is the elegant and sensual movement of the bust, an attitude rather than a shape which is free from the prescriptive restrictions of a comparing image rich in details as the glazed photograph of the movie star in Rockwell’s painting (Fig. 2).

An important scientific discovery occurred in the Nineties of the 20th century has further developed the understanding of the functioning of our nervous and motor system: mirror neurons “have revealed the existence of an understanding mechanism through which actions made by others, detected by sensorial systems, are automatically transferred to the motor system by the viewers enabling them to have a motor copy of the observed behaviour as they were the ones to display it”. The neurons that carry out such transformation of the action from a sensorial format to a motor one have been called mirror neurons.” [8].

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s work investigates the cognitive functions of the mirror and our inner mirrors. Among his first works in the Sixties stand out the “mirror paintings” in mirror-polished steel dealing with the core themes of the discourse of art as perspective, therefore space, time, the inclusion of the audience in the work. Referring to these works the artist says: «I am sure there is always a relationship between past and present because the present inevitably reflects the past. With my Mirror paintings I completely opened perspective. Before us we see all the things that exist. Differently, in the mirror we also see the rest, what lies behind us. My discovery was a double perspective. During the Renaissance, there was only frontal perspective, but now with the mirror painting perspective looks back in space and time. To me, the past meets the present to create the future». [9]. The past is given by the photography of one or more figures that are static in the work whereas the present is composed by the living reflections of people observing and interacting with the mirror.

2.2 Double – Splitting

According to the popular superstition, breaking a mirror and consequently the image results in bad luck: maybe because it tangibly translates the fragmentation of the identity, therefore the crisis. Reflex’s mirror Impact has a deep crack repaired with gold as in the Japanese tradition of kintsugi. This ancient technique is in perfect balance between craftmanship and meditation exercise. In this technique broken pottery is repaired with a golden binder making the flaw precious instead of hiding it. Transferring this technique to a mirror seems to be suggesting that the obsession for physical perfection, therefore conformity, makes one neglect elements of uniqueness that should be enhanced, which is to say the flaws.

In his writings about the Double, Freud investigates the boundaries of the diurnal, familiar, aware context that he defines as Heimlich and its opposite Unheimlich, the Uncanny, what should remain hidden in a process of repression and yet comes to light. The uncanny manifests itself when before our eyes appears something familiar that has been repressed and the boundary between fantasy and reality becomes blurred, but only rarely degenerates into neurosis.

This happens more often in cinema. Psycho is an example of that. Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is divided between his own identity and his mother’s. He is not the only double character of Alfred Hitchcock’s drama: the female protagonist Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals from the company she works for in order to run away with her lover. However, while trying to reach him she stops at the Bates Motel to sleep and has a crisis of conscience. The two protagonists meet in a mirror in the reception of the hotel, and this is the first subtle hint of the ambiguous and dual nature of the ordinary, shy guy Norman Bates seems to be. The audience already knows Marion’s dark side. Yet, in a moment she inextricably bonds with Bates’ guilty and immoral half. Locked in her room, Marion counts money and, even if she is torn, decides to give it back while the mirror is reflecting her double, the two possibilities for her life in that moment: running away towards happiness (maybe) or going back living a modest yet honest existence. Both possibilities, that have become images, crumble with the violent death of the character.

Worried about her sister, Lila Crane (Vera Miles) looks for the elderly mysterious woman roaming in Bates’ house. She sees her image reflected in a double mirror and gets scared because she thinks she has seen somebody behind her. Psycho is an incessant play of mirrors: eventually Bates’ mask wins, his double, and what remains alive in him is his mother’s personality.

Hitchcock’s mirrors reveal the characters’ dark side. As Virginia Woolf writes, maybe: “People should not leave looking-glasses hanging in their rooms any more than they should leave open cheque books or letters confessing some hideous crime.”.

2.3 Door to Fantasy

Alice’s mirror is the door to an oneiric and imaginary place, Wonderland, that represents our parallel world, the subconscious. Alice passes through the mirror and finds a system of overturned rules and fascinating nonsense as happens in dreams and elaborate memories. Lewis Carroll’s texts and its sequel, Alice through the Looking-Glass, [10] open up to endless possible interpretations even if the imaginative potential offered by the mirror as door to another world is always connected to the object (Fig. 3).

An example of that is the luminous mirror Ultrafragola designed by Ettore Sottsass Junior in 1970. The sinuous silhouette resembles long and wavy hair, and the translucent pink colour evokes the female world and a delicate skin. The mirror belongs to the Mobili Grigi series of complete bedroom and living room furnishings designed by Sottsass for Poltronova in 1970. In Italy and throughout the world, those were the years of struggles for female emancipation and sexual liberation. This rose-coloured and fairy-tale object does not evoke a “gender” childhood with dolls. On the contrary, the mirror offers its interpretation to the viewer. It is the same size as a door and when the mirror is turned on in the dark it creates the illusion to be able to pass through it and enter another world, make a subversive and radical gesture as the one made by brave and insolent Alice.

Jean Cocteau takes inspiration from this topic of imaginary literature to include in his film Le sang d’un poète (1930) [11] a scene where the poet goes through the mirror, maybe metaphor of the artist’s inability to adapt to the real world and his tragic and resolute choice to escape from it.

Other freestanding mirrors directly or indirectly evoke the door: this is the case of Caadre by Philippe Starck for FIAM framed in curved glass or Mirage by Alain Gilles for Buzzi, arch-shaped trompe-l’œil with perspective illusion of depth painted in black.

2.4 Vanitas

“Mirror mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” For the evil Queen of Snow White, the mirror is a sort of a dark conscience. In the film version Snow White and the Huntsman (2012), the mirror personifies and becomes a shape enveloped by a reflecting golden cape as a sort of an alter ego of the Queen. The mirror with build-in light by Philippe Stark allusively called La Plus Belle (2019) takes inspiration from the Queen’s question. Who is the fairest of them all? The Queen symbolizes criminal vanity able to commit the most atrocious crimes in order to continue being the most beautiful woman despite the limitations of age.

The comedy of vanity (1934) by Elias Canetti depicts a dystopic society with dictatorial regime, sad picture of the Germany of the time. The regime bans mirrors and generates an abnormal proliferation of adulation leading people to admire themselves in the words of others. Any reflecting surface becomes smuggle good, banned yet desired to see and recognize oneself. After losing their image, therefore their identity, the characters of the play wander like shadows looking for the body that has generated them.

In a specific moral popular tradition, the mirror can have diametrically opposed values: on one hand, it is a demoniac object leading to perdition, on the other, it is an instrument to meditate about the caducity of life observed while passing on one’s body. The first value includes a detail of The Garden of Earthly Delights (1480–1490) by Hieronymus Bosch. In the lower right part of the panel of Hell there is a young, unconscious woman seated with a toad on her chest and grasped by a demon with reptile paws. The lady and her satanic predator are reflected in a black convex mirror, which is the bottom of another demon. Probably this position of the mirror evokes a popular French tradition saying: Le miroir est le vray cul du Diable [12]. The mirror is a deceptive and demoniac object: maybe the girl has spent too much time looking at herself in the mirror and this is the punishment.

In the second family of vanitas with mirrors belong the numerous penitent saints like The penitent Magdalen (1639–1643) by Georges de La Tour, traditionally portrayed with the features of the meditation about time passing by and beauty vanishing: the skull, the candle and the mirror. A similar and more recent representation is the Girl at the Mirror (1921) by Otto Dix, a young woman seeing her own skeleton reflected in the mirror.

An author managed to include in his product the features of the mirror-vanitas and to update its meaning, even if his work is still a cryptic object: Man Ray. In 1938, he makes a large mirror where he writes Les Grands trans-Parents by hand. Since 1971, a smaller version has been produced for Cassina and continues representing an enigmatic domestic object leading to reflection (in both senses). Genius of titles, with this object, Man Ray reflects our image reminding us that what is “large” is “transparent”, in other words, the most important things are often neglected or taken for granted, paraphrasing the Little Prince’s “what is essential is invisible to the eye”. Moreover, grand-parents in French means grandparents, therefore our past. This is a personal, biographical reference, a reference to time that goes by inexorably. This mirror can be considered as a contemporary vanitas because it forces us to look at tangible things, namely our reflection in front of us to find something more profound and essential.

2.5 Mirror and Soul

The connection between mirror and soul is the origin of the typical features of demoniac creatures. According to a significant popular and literary tradition, some of these creatures (including vampires) do not reflect their image because they have no conscience. In Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker the inhuman nature of the Count is revealed through the mirror, which does not reflect his image. This episode was also portrayed in the numerous screen adaptations of the novel.

The mirror is connected to the eye and sight as instruments to know the outside world and to reflection as a tool to know the inside world. For this reason, it is often connected to the iconographies of Truth and Prudence represented while holding and contemplating this object. A contemporary mirror depicts an eye, evoking a long tradition: this is Eyeshine Mirrors (2015) by designer Anki Gneib for Thonet.

A curious object is the Psyche or Psyché, a swinging mirror that becomes popular in the 19th century and that reaches its peak in France during the Second Empire. It is assembled on a structure with two side feet and a pivot to adjust the orientation: in this way it is possible to frame the whole figure including when the distance from the mirror and the height of the person change. This is why it is used in bedrooms and tailor’s shops. In Apuleius’ tale, Psyche (in Greek: soul) is a beautiful woman in love with Cupid and the myth represents the reconstruction of a unity through sentiment.

Some the most significant models of Psyche are Thonet’s ones as 9951 [13], characterized by sinuous floral lines of the Franco-Belgian art nouveau and number 9953 [14], more like the rigorous and geometrically-inspired lines of the Vienna Secession, both included in the 1904 catalogue of the company. The model 9951 appears in the film Landru (1962) by Claude Chabrol based on real-world crimes that took place during the First World War. In some frames one can only see the reflection of the ruthless French serial killer as if Psyché could show the duplicity of that fascinating bearded man and to separate the soul, which has become image, from the body.

According to the same metaphor, eyes themselves are popularly referred to as “the mirrors of the soul” because they reflect- or betray – the character, the mood and the intention of a person. If the gaze is pointed towards oneself, self-contemplation leads to narcissism and vanity (in Latin vanitas). And we are back to Narcissus.

2.6 Mirror and Sexuality

Katoptronophilia [15] (from the Greek katoptron, mirror + philia, love) is the sexual attraction towards the observation of one’s image in the mirror during sexual activities. This paraphilia frequently coincides with a narcissist profile. To satisfy it, rooms surrounded by mirrors or reflecting surfaces covering the whole house are often designed.

There are numerous stories about fetish in cinema as The Dreamers (2003) by Bernardo Bertolucci and American Psycho (2000) by Mary Harron. In the latter, there is a scene where the protagonist Patrick Bateman, performed by Christian Bale looks at himself in the mirror while he is having sex with two prostitutes that cannot distract him from his reflected image that has become, as for Narcissus, the real unattainable object of desire.

3 Techniques

3.1 Double Mirror – Multiplication or “Mise en Abyme”

Las Meninas (The Ladies- in- waiting, 1656) is a painting oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez. The mirror in the centre of the image shows what is happening outside the image portrayed in the canvas exactly where the viewer is. The vision catoptric machine produces a space-time absurd, projecting the viewer into the canvas in a different time captured by the magnetic look of the painter who is actually looking at a mirror to portray himself. Therefore, it is assumed that in this room there are two mirrors facing each other, at least during the pose. As a result, the viewer is fascinated by this play of multiple reflections.

The same mechanism can be found in a common domestic object that tickles children’s imagination: the double wardrobe with mirrors inside the two doors. By opening it, one finds itself catapulted into a long corridor filled with endless copies of oneself perfectly moving in unison as a harmonious corps de ballet. It is a “mise en abyme”, a story in the story, or an image in the image reproducing itself potentially infinitely. There are numerous good examples of this literary figure both in photography and cinema. Orson Welles uses it in Citizen Kane (1941): in the scene leading to the epilogue the protagonist Kane, performed by Welles himself, stands in between two mirrors and repeated infinitely as a robot or a cog in the wheel, literally sank into the abyss of an eternal reproduction of the same.

3.2 In photography and Cinema

As noted with regard to Psycho, among the masters of the use of mirrors in cinema Alfred Hitchcock stands out. In The Wrong Man, 1956, Henry Fonda looks at himself in a broken mirror in the moment of truth and pain when he finds out his wife is seriously ill. In the film Vertigo, 1958, the director uses the mirror to create a composition able to anticipate the splitting of characters that create fictions, masks and replacements throughout the movie until they disintegrate their identities in a criminal kaleidoscope culminating in tragedy.

In both cases mirrors are real. However, in theatre and cinema there are illusory mirrors too. Actors stand in front of the audience or camera but act and observe themselves as if they were in front of a mirror actively engaging the audience. There are numerous examples of illusory mirrors in Quentin Tarantino’s works, especially in Pulp Fiction (1994) and in Fight Club (1999) by David Fincher.

Whenever directors use real mirrors, they, their camera or any other equipment or stage light could appear in the framing. Despite this, they run the risk because by multiplying images they can convey the sense of an intimate dichotomy, an incurable identity break affecting characters. There are two recent films where protagonists live their existential tragedy in front of the mirror. The first is Black Swan (2010) by Darren Aronofski with an Oscar-worthy performance by Natalie Portman as a ballet dancer dancing Swan Lake. From the beginning, mirrors fragment her image blending it with the image of the other dancers of the corps de ballet. When she gets to the dressing room of the prima ballerina the split between the white swan and the black swan intensifies. The two swans represent her split personality until the mirror breaks marking the tragic ending. The second film is Joker (2019) by Todd Phillips. The protagonist studies himself in the mirror and through the image finds his real identity and progressively transforms into the ruthless and cynic noir mask as a painter who has chosen to paint his own self-portrait on the skin rather than on canvas.

3.3 Deforming Mirrors

The Hall of Mirrors.

The Hall of Mirrors in Versailles marks the culmination of the season when great representative galleries in royal apartments were extremely popular. It was designed by court architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart to celebrate the splendours of the Sun King. It was decorated in a Rococo style and illuminated by three-thousand candles that used to reflect themselves in the mirrors creating the illusion of finding oneself in a golden magical lantern. The technologies of the time made the production of large-sized mirror surfaces difficult and expensive. In the eyes of the visitors of that time, this would make the opulence of the hall and the magnificence of the king even greater.

The success of the Hall of Versailles in the late 17th century generates a large number of emulators like Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Rome embellished with a Gallery of mirrors coming from Venice. One can imagine how expensive it was in terms of money and means of transport to move such mirrors at the beginning of the 18th century.

The optic effects in these aristocratic galleries are image multiplication, distortion and fragmentation. The result generates the “wonder” that is well suited to the Baroque sensitivity but that has found a new strength also in the current popular tradition of this typology: the gallery of deforming mirrors at the circus or in themed amusement parks. Today, what is even more popular is the system of filters on the phone for selfies to modify one’s image as a deforming mirror. Thanks to its nature or to specific weather conditions, glass can also become a deforming mirror and transform the forest of skyscrapers of modern cities into a sort of open-air Galerie des Glaces. The most common deforming mirrors are wavy, concave or convex: these two latter types of mirrors are so fascinating that merit more specific detail.

Concave Mirror.

The convex mirror tends to deform images with the fish-eye effect. Differently, the concave mirror reverses and compresses them, but above all acts on the luminous radiation and converges the rays that it reflects to one point.

The historically best-known example of functional use of the concave mirror is the one carried out by Archimedes in 212 B.C. when the Romans besieged the city of Syracuse during the Second Punic War. To defend it by sea and by land, Archimedes uses a series of machines he invented, he specifically positions concave mirrors along the shore or more likely a series of flat mirrors arranged in such a way as to behave as a concave burning mirror and concentrates solar rays on the enemies’ wooden ships until they catch fire [16]. This episode is not described by the historians of the time, but it appears in late narrations. Combined with other recent scientific simulations, this suggests that it partially is the result of a reconstruction a posteriori. Anyway, the fascination of the burning mirror is such as to raise the interest of scholars from different fields and ages, from Leonardo da Vinci to the engineers of the MIT.

Whether it can actually start fire or not, the concentration of solar rays in one point generates large amounts of heat. For this reason, concave mirrors are used to build the solar kitchen, mostly in the warmest third world countries and refugee camps. The solar oven uses solar energy with the same system of the burning mirror but in this case the result one expects is making dinner, not burning it. Moreover, thanks to this device it is possible to sterilize water to make it drinkable. There are two types of solar oven: box cookers, called kyoto boxes, which are easy to make at home with cardboard covered in aluminium foil, reach low temperatures, and have a long cooking time and parabolic cookers composed by a parabolic mirror that can cook rice for eight people in 25 min. Numerous websites explain how to make a solar cooker or sell them in different sizes, including portable camping cookers with solar and electrical power source (in the event of bad weather) [17]Footnote 1.

The restaurant Solar Kitchen [18] is an experiment resulting from the genius of the Catalan designer Martí Guixé and the Finnish chef Antto Melasniemi. It is an itinerant project that follows the sun throughout Europe building every time an outdoor solar kitchen surrounded by customers’ tables. The menu changes according to the weather: if the sky is cloudy, one shall be content with a salad, but this teaches to rediscover flexibility and rethink one’s own rhythms according to nature and respecting it.

Convex Mirror.

The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) by Jan van Eyck portraits on the back wall a convex mirror that reflects and deforms the scene showing what the cinema would define the reverse shot of the scene. In the Fifties, the Italian artist Piero Fornasetti (1913–1988) makes the mirror Van Eyck with a black wood moulded frame literally reproducing the frame of the painting [19]. He replaced the miniatures on the frame with small convex mirrors, a recurring motif in his rich production called “bolla” (bubble). The prototype used to include a convex reflecting surface at the centre too. Differently, the following re-editions, currently still in production, include a flat mirror: the fascinating object of the flaming painting has become an everyday utensil, but it has maintained a powerful imaginative feeling. On several occasions, Fornasetti re-elaborates the drawing of the mirror Van Eyck in his sketches transforming the shape into an oval or a rectangle. Probably, this ongoing re-interpretation feeds the works of those years. He produces numerous round mirrors with brass frames, secured with nails or long ribbons of coloured velvet. The surface is convex or flat but decorated with convex bubbles. His mirrors Collier, framed by a golden pearl necklace, and Raggi di sole with a golden radial frame, are iconic too. The image reflected by the mirrors with bubbles is fragmented and deformed in a self-mocking mosaic possibly representing the impossibility to limit the individual to a unitary and flat image as Lacanian mirror stage intended and offering as unique dimensions “no one and one hundred thousand” (Figs. 4 and 5).

Now, let’s go back in time and let’s move to Rome. The inventory drafted for a requisition in 1605 testifies the presence of two mirrors in Caravaggio’s atelier: a large flat mirror he used for self-portraits, to check the composition or direct natural light towards the object and a small convex mirror, probably used to converge rays uniformly on the models including when the position of the sun changed [20]. We find this mirror, or a similar one, portrayed in the painting Martha and Mary Magdalene (1598).

To explain his classes about perspective at the Royal Academy, William Turner produces a series of drawings depicting the reflections on a single and double metal sphere. The drawing exercise borders on virtuosity and reflects a diffuse interest in convex reflecting surfaces. It is no coincidence that his friend and architect John Soane positioned numerous circular convex mirrors in his London museum-house specifically in arches and in the lowered ceiling of the Breakfast Room. Deceptive reflections seem to produce voids and dematerialize the load-bearing elements of the architecture itself resulting in an atmosphere of extreme levity.

3.4 “Functional” Mirrors

There are numerous mirrors that are used in scientific instruments as telescopes, microscopes, laser rays and astronomical observatories or to increase road visibility, send Morse signals or, as Archimedes showed us, start fire.

Traffic Mirror.

Differently from the rear-view mirror, which is flat, the traffic mirror is slightly convex so it can improve the visibility even when it is low reflecting a large field of vision in a small space. Yet, it must be positioned at the adequate height and according to an accurate incline in order to be really useful otherwise it is just a deforming mirror.

Rear-view Mirror.

Perseus managed to behead Medusa by looking at her reflection in the shield used as a mirror to avoid being turned to stone. He put the head in a bag and used it as a weapon before giving it to his protector Athena that placed it on her shield. In the Harry Potter saga a dreadful serpent, the basilisk, infests Hogwarts castle and kills whoever looks at it directly in the eye and petrifies who sees its reflection. Any reflecting surface can be a rear-view mirror. In this sense, one cannot forget the renowned framing in Kill Bill (2003) by Quentin Tarantino where Uma Thurman looks at the blade of her katama sword to study her enemies behind her and to hit them with confidence, as if she had eyes in the back of her head. If used properly, a mirror surface can expand the operating scope of our visual organs to protect us from dangers that otherwise we could not perceive. The rear-view mirror of our car acts as a shield (reversing Perseus’ equation shield-mirror). Many sculptors use mirrors to check their works from different perspectives and, after finishing, the hairdresser gives us a compact mirror to check if our hairstyle is perfect including where we cannot see it: mirrors enhance the action of our eyes.

4 Conclusions

The connection between subject and things can become a bond of identity as the one between ancient gods and their symbol (Zeus-thunderbolt, Neptune-trident, Apollo-lyre…) or between saints and their instruments of martyrdom or prayer (Saint Catherine- wheel, Saint Sebastian-arrows, Saint James-shell). However, at the same time it is also an instrumental or prosthetic relationship like the one between surgeon and scalpel, tennis player and racket, office worker and computer.

Thinking about the profound values of objects entails a critical perspective on the material landscape surrounding us, which is essential to the comprehension and the project. Concept maps can help students to develop an integrated design method enabling them to create new objects knowing their meanings and values: objects that are ready to turn into things.

References

Bodei, R.: La vita delle cose, 1st edn. 2009, p. 55. Laterza, Roma-Bari (2019)

Eco, U.: Sugli specchi. In: Sugli specchi e altri saggi, pp. 9–37. Bompiani, Milano (1985)

Borges, J.L.: La biblioteca de Babel (The Library of Babel), short story included in the collection El jardin de senderos que se bifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths). Sur, Buenos Aires (1941)

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book III, 8 B.C., vv. 339–510. (8 AD); Editio princeps Baldassarre Azzoguidi, Bologna (1471)

Cocteu, J.: Le Sang d’un poète, surrealist movie, 49’, Charles de Noailles, Paris (1930)

Lacan, J.: The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I, Ecrits, orig. ed. 1966, pp. 1–7, Tavistock Publications, London (1977)

Rossi, V.: Silvia, published as a single in 1977 and included in the album...Ma cosa vuoi che sia una canzone... in 1978

Entry “Mirror neurons” of the Italian encyclopaedia Enciclopedia Treccani online (Consulted on 3 January 2023 and translated by Mariachiara Girelli). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/neuroni-specchio_%28XXI-Secolo%29/

Cipriani, C.: Pistoletto: è nell'arte la vera rigenerazione sociale, Il Quotidiano di Puglia, Saturday 26 Oct 2019. https://www.quotidianodipuglia.it/cultura/carmelo_cipriani_la_venere_degli_stracci_non_e_soltanto_una_delle_opere-4822133.html. Consulted on 3 January 2023 and translated by Mariachiara Girelli

Carroll, L.: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Macmillan, London (1865)

Carroll, L.: Through the Looking-glass, and What Alice Found There. Macmillan, London (1871)

Baltrušaitis, J.: Lo specchio: rivelazioni, inganni e science-fiction (orig. ed., Le miroir: révélations, science-fiction et fallacies, 1981), pp. 19–56. Adelphi, Milano (2007)

Thonet, Thonet bentwood & other furniture: the 1904 illustrated catalogue, p. 77, nr. 9951, Dover Publications, Mineola, NY (1980)

Catalogue Thonet 1904, p. 128, no. 3

Meredith, G.F.: Worthen, Sexual Deviance and Society: A Sociological Examination. Routledge, New York (2016)

Vacca, G.: Sugli specchi ustori di Archimede, Bollettino dell’Unione Matematica. Italia, serie II, a. III, n. 1, Bologna (1940)

http://www.herbangardener.com/2010/07/15/how-to-build-a-solar-oven/ https://gosun.co/collections/solar-ovens. Consulted on 3 January 2023

http://solarkitchenrestaurant.fi/ http://www.guixe.com/projects/Solar_Kitchen/Lapin_Kulta_Solar_Kitchen.html. Consulted on 3 January 2023

Casadio, M., Fornasetti, B. (eds.) Imageries allo specchio, in Id., Fornasetti, 286–305, Electa, Milano (2009)

Missing references in the text:

AA.VV. Specchio, in L’uomo e i simboli, Enciclopedia tematica aperta, pp. 367–371. Jaca Book (2002)

Biedermann, H.: Enciclopedia dei simboli (orig. ed., Knaurs Lexicon der Symbole, 1989). Garzanti, Milano (2011)

Dolto, F., Nasio, J.D.: L’enfant du miroir. Payot, Paris (2002)

Guillerault, G.: Le miroir de la psyché. Gallimard, Paris (2003)

Macchi, G.: Lo specchio e il doppio: dallo stagno di Narciso allo schermo televisivo. Fabbri, Milan (1987)

Marchis, V.: Lo specchio. In: Id., Storie di cose semplici, pp. 85–108. Springer Verlag, Berlin (2008)

Melchior-Bonnet, S.: Storia dello specchio, foreword by Jean Delumeau, Bari, Dedalo (2002) (orig. ed. Histoire du Miroir, Paris, Imago, 1994)

Phay, S.: Les vertiges du miroir dans l’art contemporain. Les presses du réel, Paris (2016)

Roussillon, R.: Le transitionnel, le sexuel et la réflexivité. Dunod (2009). https://doi.org/10.3917/dunod.rous.2009.01

Simeone, E.C., Tateo, A., Guglielmi, M.G.: Lo specchio e il doppio tra pittura e fotografia, Aracne (2009)

Thévoz, M.: Le miroir infidèle, Les Editions de Minuit, col. Critique (1996)

Vidler, A.: Il perturbante dell'architettura. Saggi sul disagio nell'età contemporanea, Turin, Einaudi (2006) (orig. ed. 1992)

Webster, R.: The cult of Lacan: Freud, Lacan and the mirror stage (2002)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Berselli, S. (2024). Through the Mirror. Concept Maps to not Lose (One’s Way Between) Objects. In: Zanella, F., et al. Multidisciplinary Aspects of Design. Design! OPEN 2022. Springer Series in Design and Innovation , vol 37. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49811-4_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49811-4_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-49810-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-49811-4

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)