Abstract

This chapter focuses on the challenges of implementing mission-oriented policies (MOPs) in developing countries, with a particular emphasis on the Brazilian shipbuilding sector. The aim is to analyze the difficulties associated with setting MOPs and their impact on market creation and innovation. Despite the implementation of comprehensive institutional arrangements to foster technological and industrial development, the sector’s progress has been hindered by coordination uncertainties and high capability-building costs. The policies initially provided a boost, but the industry ultimately failed to catch up with international competitors. The article highlights the blurred boundary between policy expectations for market creation and the practical limitations of building a thriving industry.

I’m grateful for financial support from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) under grant number 486501/2012–4 as well as to the program Erasmus+ Staff Mobility 2022, and to Christian Sandström and Magnus Henrekson for their invitation, comments, and insights.

Selected content is from Author’s Doctoral Dissertation Industrial Organization Dynamics: Bounded Capabilities and Technological Interfaces of the Brazilian Shipbuilding and Offshore Industry at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Codes

Introduction

Innovation has long been acknowledged as the primary driver of economic development and prosperity, a concept that gained prominence through the contributions of Schumpeter. As a result, it is considered a top priority and often an ultimate objective for policymakers. Although innovation stems from the entrepreneurial endeavors of companies aimed at introducing valuable solutions to the market, firms do not exist in a vacuum. They are embedded social/market relations (Polanyi and MacIver 1957; Granovetter 1985) and institutions (North 1991), where governments have a direct and indirect influence on the rate of innovation and development that can be achieved. However, “getting institutions right” to foster development presents considerable challenges and is fraught with uncertainty.

In recent literature, there has been a growing recognition of the historical significance of governments in influencing the course of change and market dynamics through their role in fostering innovation. In this sense, governments should go beyond the regulation of markets and correction of “market failures,” but they can actively contribute to the creation and shaping of markets by implementing targeted policies that prioritize innovation-driven missions (Mazzucato 2013, 2015). However, the effectiveness of the employment of such government tools is open for debate (Ergas 1987; Brown and Mason 2014; Foray 2018; McKelvey and Saemundsson 2018).

This holds a particular significance for developing nations, as they prioritize innovation policies and investments in research and development (R&D) to enhance their overall sectoral capabilities within specific industries and markets, both established and emerging (Kim 1980; Kim and Nelson 2000). In these contexts, traditional sectors concentrate on an initial stage of catching up, which can potentially serve as a pathway for leapfrogging in the future (Lee and Lim 2001). The dual nature of innovation policies in developing countries creates ambiguous boundaries when it comes to market creation. However, this observation also sheds light on the challenges associated with mission-oriented policies and claims for the creation of markets. The question is, at what cost? In this chapter, it is argued that MOPs need to cope with the puzzle and impreciseness of both “building innovation capabilities for market creation” and “market creation for building innovation capabilities” (Alves et al. 2021).

Given bounded rationality and the inherent uncertainty in decision-making processes, it becomes challenging to anticipate the behavior of economic agents and the extent to which they can be trusted to build the required innovation capabilities. The inability to rationally convert policy innovation efforts into concrete packages of technological and operational capabilities that will produce the expected positive outcomes leads to an innovation paradox where developing countries often have negative returns on R&D and innovation investments (Cirera and Maloney 2017). This process also contributes to the stagnation of these nations into what is called the middle-income trap (Griffith 2011; Lee 2013).

This chapter examines and explores the key challenges associated with implementing effective mission-oriented policies in developing countries. To illustrate these challenges, I analyze the successes and limitations of a specific mission-oriented policy implemented in the Brazilian shipbuilding sector. This sector experienced a significant growth in recent years, supported by a comprehensive institutional framework aimed at technological catch-up, industrial development, and innovation. The policy gained a momentum in 2005 following the discovery of giant oil fields in the ultra-deep waters along the Brazilian coastline, known as the Pre-Salt region. Measured against such high expectations, the strategy cannot be said to have fully succeeded. While the set of policies put in place managed to mobilize a large number of actors and resources around the country in the pursuit of becoming a global player in this market, the industry ultimately failed to catch up and innovate.

From Institutions to Missions

Institutions and policy play a crucial role in setting the course of inventive and economic activity (Bush 1945; Arrow 1962; Langlois and Mowery 1996). They set the “rules of the game” by which economic agents make decisions (North 1991), but they are also often used to foster endeavors toward technological change, innovation, and the underlying production systems within an economic structure (Edquist 1997).

As an evolutionary process, institutions and the technological structure of regions co-evolve to produce comparative advantage (Nelson 1995), which creates potential windows of opportunity for technical and economic transformation (Lee and Malerba 2017). Yet, getting these institutions and policies right remains a major challenge (Williamson 2009), which often creates unintended consequences and unpredicted costs as they are based on optimistic views of complex and intractable problems (Morris 1980). These challenges may be even more critical in the context of emerging economies given the cruder estate of preexisting technological capabilities, internal market, and industrial and general institutions for innovation (Rodrik 2009). Mission-oriented policies (MOPs) have presented themselves as a potentially attractive policymaking vehicle to overcome the lack of appropriate institutions and complexities behind the implementation of industrial and innovation endeavors in emerging economies.

Mission-Oriented Policies and Industrial Innovation

The twentieth century, especially after the post-war period, has presented several mission-oriented programs. In the United States, this process has been notorious through endeavors such as the Apollo space program, research on cancer, and several other defense-related programs (Mowery 2010; Pisano and Shih 2012). Fisher et al. (2018) provide an extensive coverage and interpretation of mission-oriented policies with significant innovation results across various countries stressing the need for a mix of appropriate policy instruments, social approval, accountability, and a sense of urgency. The question lies in the continuation and sustainability of such initiatives without governmental incentives.

According to the mission-oriented policy advocates, different than the conventional economic approach of government whose intervention focuses on the regulation and correction of failing markets, mission-oriented policies (MOPs) look beyond by “creating new markets” as a result of the proactive state’s role in fostering innovation-led growth and development (Mazzucato 2013). The state’s role can create new markets through significant public procurement (Edquist et al. 2015). MOPs are also expected to achieve the specific goal by setting up institutions to promote education and skills, by building infrastructures to support innovation, and by shaping long-term behavior (Mazzucato and Penna 2015), as well as by giving governments a strategic role in providing the necessary finance for innovation (Mazzucato and Penna 2016).

However, successful MOPs require the strong buy-in and engagement of the private sector beyond governmental policy. While governments can create the right conditions, ultimately management decisions will determine what happens (Pisano and Shih 2012, p. 20). In this sense, it is argued that MOPs differ from the so-called old missions, which are said to be top-down policy decisions (such as the creation of government agencies such as NASA and major initiatives relating to national defense, space exploration, and public health). New missions, on the other hand, should encourage bottom-up stakeholder-based initiatives (Mazzucato and Penna 2015). Table 1 below brings forth some of the argued differences between types of missions.

Thus, it is understood that missions must be well-defined, comprise a portfolio beyond research and development (R&D) projects, involve different types of actors, and engage in joint policy decision-making (Mazzucato and Penna 2016). Policies should include specific targets, organization, evaluation and assessment, risk, and rewards (Mazzucato 2013, 2018; Fisher et al. 2018).

MOPs are expected to achieve specific goals by creating the necessary incentives to save and invest, setting institutions to promote education and skills, building infrastructures, and shaping a long-term behavior. To achieve such goals, MOP is based on a fourfold set of elements (Mazzucato 2018): it should (a) apply an ambitious challenge translated into routes and directions, (b) nurture organizational capabilities, (c) establish new forms of assessment, and (d) offer a better sharing of rewards and ease risk-taking so that innovation-driven growth can also result in inclusive growth. With this said, we explore some potential limits to market creation.

Can MOPs Really Create Markets?

One of the main claims for MOPs is the supposed capacity of creating markets rather than correcting for market failures (Mazzucato 2013). To understand this claim, it is important to first address what markets are and how they arise and work. Functioning markets presume the co-existence of producers and consumers that interact and exchange by means of economic transactions to supply and satisfy the needs of value. Hodgson (1988) maintains that the closest definition of a market is the one provided by Mises (1949, p. 257) where he states:

The market economy is the social system of the division of labor under private ownership of the means of production […] The market is not a place, a thing, or a collective entity. The market is a process, actuated by the interplay of the actions of various individuals cooperating under the division of labor.

Firms are the key players in this process as they, by means of transaction, are the direct interface to the consumer or buyer. As the main institutions of the economic system, firms and markets are inexorably inseparable or even considered alternative ways to organize the economic activity (Coase 1937). Thus, a workable market presumes, on the one hand, a relation of needs and demands to be satisfied by some economic agents and, on the other, the ability to fulfill those needs through production by other economic agents. Firms are only valuable as long as they are able to fill some market gap and, consequently, transact and profit from whatever solution it provides.

From the perspective of “transaction cost economics” (TCE), a hierarchical structure will “naturally” arise and grow until it inevitably meets with the market for buying or selling, in other words, where it can engage in transactions with other economic entities, such as other firms or consumers. Firm boundaries and ability to grow, therefore, arise from this techno-economic logic of mastering the same routines and capabilities (Nelson and Winter 1982), managing efficiently the allocation of a pull of resources (Penrose 1959) and specific assets (Williamson 1985), and relying on complementarities (Richardson 1972; Teece 1986) to solve problems efficiently and profitably. For “market creation” to be sustainable, it relies on the ability to create firms and capabilities to transact and profit from such a market. While innovation is perhaps the “purest” way to achieve market creation by firms, the question is: what is the role of governments and missions in the process and how?

According to Rodrik (2009), one way for governments to create a market is through the use of mechanisms such as local content policies, tax cuts, trade barriers, and special funding for production or even R&D. This results in a temporary reduction of transaction costs, letting economies internalize and make feasible formerly inexistent or economically impracticable capabilities. Such public incentives can work as “windows of opportunity” in laggard countries (Lee and Malerba 2017). Latecomers use such incentives to offset cost differences associated with the lack of capabilities. Geographic considerations in terms of technological and market proximities must also be considered to increase the chances of success (Orlando 2004). In countries behind the technological frontier, such types of markets are created for the sole purpose of catching up (Lee 2019).

However, windows of opportunity are always temporary, and the “artificial transformation” of marginal transaction costs is not sustainable in the long term without generating costs. To be able to take advantage of market entry incentives created by governments, latecomer economies must find faster ways to develop capabilities at the lowest possible cost. This also requires the absorptive capacities of economic agents to convert R&D output existing technologies into production, sales, and growth (Aldieri et al. 2018).

While, in theory, MOPs can be set to directly change and create new markets, fostering the conditions to build local capabilities that will support firms to populate the market is unavoidable. A precondition of market creation requires the building of capabilities that are often difficult to master and costly to develop. The mismatch between the positive expected intent and what is achievable based on the availability capabilities at any point in time creates a “fuzzy boundary” that often leads to the unsuccessful implementation of missions (Alves et al. 2021).

Capability-Building Costs in Catching up and Innovation

Catching-up theory postulates that backwardness learning provides an opportunity for fast growth from latecomer economies with lower costs (Abramovitz 1986). However, this process is dependent on previously existing conditions including knowledge, education across economic agents (firms and individuals), and managerial skills that when not present create high uncertainty and decrease the probability of success (Cirera and Maloney 2017). That’s where the intent for market creation becomes blurry. While policies, as stated in the MOP literature, can define the goal and direction of change, the unavailability of ex ante capabilities generates higher capability-building costs. These costs are hard to predict even with the best estimates as they depend highly on the speed of learning of firms in each context.

For instance, R&D investments are required to accelerate the learning of firms to both use freely available knowledge (Nelson and Winter 1977) and access a network of information (Rosenberg 1990). Adoption or imitation costs will vary dramatically based on the technological level achieved by firms in a country (excluding the costs of factors). This becomes even more problematic for less industrialized countries unless there is a window of opportunity to be exploited (Rip and Kemp 1998).

The ability to create a market and conduct transactions economically is undermined by the failure to master and coordinate various complementary competencies. Complexity in the knowledge and the number of technological interfaces can generate friction beyond transaction and production costs (Alves 2015). Some of these are technological transfer costs (Teece 1977). Others are related to coordination decisions such as suppliers switching costs (Monteverde and Teece 1982). Capability-building costs are similar to what Langlois (1992, p. 113) calls dynamic transactions costs, that is, the “costs of persuading, negotiating and coordinating with, and teaching others” or, simply, “the costs of not having the capabilities when you need them.” Capability-building costs are dynamic learning costs that must be taken into consideration by mission-oriented policies in emerging economies as they will influence the economic scope and the rate at which new industries can and will dynamically grow.

The “New” Mission Case: Policy for Innovation in the Brazilian Shipbuilding and Offshore Industry

The new mission for the resurgence of Brazil as a shipbuilding superpower was grounded on a window of opportunity and a wave of optimism coming from international growing markets before the 2008 financial crisis.

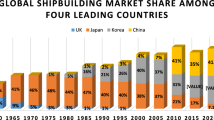

Brazil has a long history of shipbuilding, dating back to the sixteenth century. It experienced a significant growth during the 1950s. The establishment of the Merchant Marine Fund (FMM) and the National Development Bank (BNDES) aimed to rejuvenate the national fleet, reduce ship imports, and stimulate exports (Foster 2013). This led to substantial foreign direct investment and the establishment of major shipyards in Rio de Janeiro and international companies such as Ishibras and Verolme. By 1975, Brazil was the world’s second-largest shipbuilding nation. However, the industry faced a downturn in the following decades due to economic challenges, tight monetary policies, reduced subsidies, and strict local content requirements. This resulted in a decline in technological capabilities, delivery delays, cost overruns, and an inability to compete (Cho and Porter 1986).

A revival occurred in the 2000s after Brazil successfully addressed its fiscal deficit and rolled back inflation. With a stable economy, a new wave of confidence emerged fostering industrial private investment and growth. A key factor in this resurgence was the discovery of significant offshore oil reserves. This created a demand for advanced oil platforms and transportation vessels, providing a boost to the shipbuilding sector. The discovery of an estimated 15 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) positioned Brazil as one of the world’s top 10 oil producers. This development serves as a focal point in the subsequent narrative, emphasizing the industry’s re-emergence and its connection to the oil discoveries.

Routes and Direction: Setting Policy to Create the Market

The exploration of Brazil’s deep-sea oil reserves required advanced technologies. Petrobras, the state-owned oil company, played a leading role in deep-water exploration, employing complex strategies and developing new technologies. The operational depth increased from 410 feet in 1977 to over 8000 feet in 2010, necessitating the expertise of specialized professionals in engineering, geology, and geophysics.

These challenges generated enthusiasm and drew comparisons to the “space race” of the 1960s, as the pursuit of technological advancements and oil production created a demand for various vessels. However, high costs and waiting times in international shipyards led Brazil to build ships and oil rigs domestically. To accomplish this quickly, comprehensive public policy interventions were implemented, culminating in a mission-oriented approach (Alves et al. 2021).

In 2002, Petrobras announced the procurement of two offshore oil rigs, P-51 and P-52, from foreign companies. This sparked opposition from labor unions, arguing for domestic construction to create job opportunities. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva responded to these concerns by supporting domestic production of the platforms (Foster 2013). This decision set in motion a series of legislative acts and policy changes that took place in the following years presented in Fig. 1.

Chronology of policies targeting the Brazilian shipbuilding industry. Source: Alves (2015)

The creation of the National Program for Mobilizing the Oil & Gas Industry (PROMINP) through a legislative act was aimed to maximize the participation of national suppliers of goods and services to the oil and gas industry. PROMINP was responsible for mapping national capabilities and providing training in several related fields of shipbuilding to the oil industry. In 2007, the Brazilian government established the Program for Growth Acceleration and identified the shipbuilding industry as a key national strategic sector for wealth generation and job creation (De Negri and Lemos 2011). The same year, the National Oil Regulatory Agency created a resolution establishing minimum local content requirements.

In 2010, Petrobras announced a historic capitalization of USD 120 billion to fund the exploration, development, and production of the Pre-Salt fields. The company’s purchasing power was directed toward national shipyards to stimulate the national industry to develop a supplier base capable of meeting the demands for the renewal of their fleet of platforms, tankers, and support boats. In 2011, Petrobras, alongside other major construction companies, established Sete Brasil SA, a company responsible for the drilling operations of the Pre-Salt fields, which placed several orders for drill ships to various shipyards.

The demand for oil rigs, tankers, and support vessels primarily came from companies involved in offshore oil exploration and production activities, with Petrobras playing a central role in this endeavor. In 2007, the National Oil Agency (ANP) introduced the Local Content Resolution. According to this resolution, oil concessionaires operating in Brazilian offshore fields were required to procure a minimum of 70% of goods and services from national suppliers. The National Organization of the Oil Industry (ONIP) was tasked with certifying suppliers for participation. This local content policy aimed to create a reserved domestic market for national suppliers, providing incentives for the gradual development of capabilities and capacity. This, in turn, formed the basis for Brazilian legislation defining three exploration regimes: production sharing, concession, and transfer of rights regime.Footnote 1

Under the production sharing agreement, all oil from the Pre-Salt fields is owned by the state which was guaranteed participation in the exploration in all fields. The operating firm contracted through a public bid was responsible for exploration and extraction, bearing all operational expenses, in exchange for a portion of the oil field’s value assuming all costs and risks associated with the specific field. In the concession regime, the extracted oil belongs to the operating firm for the duration specified in the contract upon payment of taxes and royalties. Lastly, the transfer of rights agreement allows the government to grant Petrobras the rights to explore and produce in specific Pre-Salt areas, up to 5 billion barrels of oil and natural gas, at the company’s own expense and risk. This serves as compensation for Petrobras’ capitalization efforts to promote the supporting industry.

Local content requirements, along with incentives such as tax exemptions and financial support, provided a foundation for promoting domestic supply. By establishing contractual connections between oil-producing firms, national shipyards, and engineering, procurement, and construction firms (EPCs), a national market for shipping vessels and parts was created, facilitating capability building across the domestic supply chain. Complementary training programs involving universities and technical schools aimed to identify national suppliers and provide necessary training in various fields.

The comprehensive set of laws, resolutions, and incentives aimed at reducing the comparative cost disadvantages faced by existing Brazilian suppliers compared to foreign competition. They also stimulated the entry of new national players into the supply chain. Credit facilitation measures also enabled firms to secure loans at lower interest rates to invest in activities related to the shipbuilding industry. Table 2 presents the resolutions aimed at stimulating capability building and providing financial support for innovation.

From Market Creation to Building Production and Technological Capabilities

With the institutional conditions in place “creating the market,” Petrobras assumed the central role as the lead firm driving the sectoral development. Petrobras was assigned three key roles: securing demand, coordinating suppliers, and managing cross-sectoral investments. These responsibilities entrusted Petrobras with the task of ensuring a steady demand for products and services, organizing the network of suppliers and overseeing investments that spanned multiple sectors.

Petrobras held the responsibility for operational activities related to oil production and the procurement of platforms and support vessels. To handle transportation and storage operations for oil products, the company utilized its subsidiary Transpetro, which required a substantial fleet of crude carriers and LNG carriers. In 2011, a separate entity named Sete Brasil was established with a focus on exploration and drilling activities. Sete Brasil took charge of placing orders for drill ships. Table 3 provides an overview of the number and values of the order books as of 2012.

The sector’s re-emergence was characterized by the establishment of multiple shipbuilding sites along the Brazilian coastline in 11 major states, with employment in shipyards expected to reach 100,000 employees (SINAVAL 2014). While modern infrastructure and equipment were being implemented in these shipyards, technological capabilities were recognized as a crucial element for the sector’s successful resurgence. Partnerships for technology transfer aimed to bridge knowledge gaps, although not all intended partnerships were formally established through contracts.

The initial requirement for shipyard operators was to either have prior experience in the industry or demonstrate a partnership with an experienced international company. National companies without significant shipbuilding experience needed to demonstrate their engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) capabilities based on their track record in complex projects and commit to establishing technological partnerships with recognized shipbuilding firms to facilitate technology transfer. Technology partners from countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, and Singapore brought specialized know-how to Brazil.

The primary objective of the examined MOP was to establish a foundation for innovation throughout the shipbuilding industry. This entailed fostering innovation capabilities across the entire value chain, starting from the main contractor (Petrobras) and extending to the “last” supplier. Additionally, Petrobras and other operators were obligated by the National Petroleum Agency to invest 1% of their operating revenues in research providers within the country, further promoting research and development activities.

As an operator, Petrobras took on the responsibility of overseeing the contractual interfaces in the shipbuilding projects. To ensure compliance with technical requirements and delivery schedules, Petrobras deployed staff members to different shipyards. This was crucial for the smooth management of such a large-scale operation. The minimum local content requirements for various types of vessels, ranging from 45 to 70% of locally sourced materials and components, were determined based on factors such as technological complexity, availability, and the time required for local suppliers to master the necessary technologies.

The company conducted a thorough mapping of potential suppliers across Brazil for each specific technology, equipment, ship parts, and materials specified in the engineering projects. According to Petrobras president’s assessor for local content at the time, the company possessed a comprehensive understanding of the gaps within the national industry with detailed documentation in several publications outlining various technologies and their feasibility for implementation in Brazil. To further enhance their knowledge and keep abreast of potential suppliers, Petrobras conducts continuous surveys through its inspectors.

These efforts are complemented by studies conducted by other institutions, such as the Development Bank, on the competitiveness of the Brazilian industry. These combined initiatives contribute to a comprehensive assessment of the national industry and enable Petrobras to make informed decisions regarding local content requirements and supplier selection. Backed by a set of major institutional setups and financial prospects, planning for local content, the shipbuilding industry was able to rapidly emerge in Brazil under the strong coordination by Petrobras to develop and manage technological interfaces and contractual complexities (Alves 2015).

The Cost of a Mission-Oriented Policy: From Market Creation to Market Failure

Since its inception in 2005, the implementation of a mission-oriented policy in shipbuilding has sparked a series of transformations in Brazil’s industrial landscape, impacting areas such as infrastructure, the value chain, research and development, as well as capital and labor. This policy mobilized significant resources, leading to a notable growth in employment within the shipbuilding sector, which eventually became the second-largest industry in the country, trailing only behind the automobile industry.

For approximately a decade, there were high hopes and great expectations surrounding the mission-oriented policy’s establishment, aimed at fostering the development of Brazil’s shipbuilding industry. However, despite the intuitional mission-oriented incentives and extensive planning, over time, these expectations started to crumble. The industry’s employment trajectory tells a story of drastic shifts, from a state of near despair in the 1980s to a rapid rise in the 2000s. Employment within the shipbuilding sector reached its peak in 2014, with a total of 82,000 jobs (Fig. 2).

Despite the significant employment growth, the shipbuilding industry in Brazil faced major challenges in terms of productivity. The industry struggled to achieve substantial output growth and grappled with high construction costs, which hindered its ability to compete on the international stage. Moreover, a lack of competitiveness combined with corruption scandals, notably the “car-wash” investigations centered around Petrobras, dealt a severe blow to the industry. As a result, by the end of 2018, the number of employees in the shipbuilding sector had dwindled to just 29,539.

As a state-owned company, Petrobras participated in shipbuilding (EPCC), with variable involvement levels. It provided shipyards or firms with the General Technical Description (GTD) developed at CENPES. Two groups at CENPES collaborated on technical descriptions and engineering projects. The Research and Development in Engineering and Production group collected surveys and advanced technology, while the Basic Engineering in Exploration and Production group focused on fundamental requirements and sometimes created basic engineering projects. When Petrobras leased oil fields, it provided technical descriptions to the operating firm, which engaged national suppliers. Petrobras inspected vessels and participated in commissioning. As the primary operator, Petrobras had three contract approaches, yielding different cost and delivery results. “Charter” contracts with less Petrobras involvement had fewer issues. Increased Petrobras’ involvement in complex projects posed difficulties, including sudden changes and project reviews during production.

In Brazil, public bids for shipbuilding projects were predominantly won by a select few domestic companies. These firms specialized in civil engineering projects of a complex nature, such as roads, bridges, dams, and industrial complexes like refineries and petrochemical facilities. These companies possessed the necessary capabilities to mobilize large resources, including labor and materials. However, it is important to note that infrastructure projects have a distinct technological foundation compared to shipbuilding. The shipbuilding industry faced critical bottlenecks, including a shortage of engineering teams, inadequate systems and tools, a lack of local suppliers near shipyards (Pires et al. 2007), and frequent delays and re-work. Table 4 illustrates some of the most cited reasons, as mentioned by interviewees in the shipyard that hindered the capability-building process.

Frequent project changes, a lack of standards and adherence, high overhead costs, external pressures, and client demands all contributed to these challenges. Additionally, the industry lacked engineering capacities, and the institutional processes for licensing and permits were slow, further impeding progress. These factors resulted in cost escalation, making it difficult to build capabilities due to the need for constant project changes and the pressure to meet deadlines. The limited window of opportunity proved insufficient given the existing local capabilities. While mission-oriented policies generate high expectations for market creation and capability building, two factors make the transition from the current state to the desired new state uncertain.

First, the duration of the window of opportunity is challenging to predict due to changing competitive conditions. Brazil’s mission-oriented policy to build local shipbuilding capabilities capitalized on high demand from Petrobras and the fact that international shipyards had a long waiting list of orders and were unable to meet the desired timelines by the Brazilian oil company. However, after the 2008 crisis, the demand for cargo ships plummeted worldwide, significantly shortening Brazil’s window of opportunity.

Second, the speed of learning and the costs associated with transitioning from existing capabilities to new or more advanced ones were also difficult to anticipate. The complexity of coordinating various interfaces and acquiring technological and organizational capabilities hindered shipyards’ ability to reach full production capacity. Without reliable organizational capabilities, meeting market demand became a significant challenge. Despite having state-of-the-art facilities and necessary assets, mastering the required routines demanded extensive knowledge, skills, and organizational capabilities.

Ten years after the implementation of the policy, the cost of producing ships in Brazil still exceeded the costs of importing them. The lack of industry-specific knowledge necessitated numerous technological interfaces with other firms. This made it harder to orchestrate the necessary capabilities and control technology transfer costs, dynamic transaction costs, and supplier switching costs. Consequently, reaping the benefits of learning curves became more challenging. Uncertain challenges requiring dynamic problem-solving capabilities contradicted the need for stability to excel in routine operations.

The deficiency in technical and organizational capabilities led various stakeholders to act opportunistically, resulting in moral hazards and corruption scandals. Beyond technical and operational inefficiencies, the “car-wash” scandals served as evidence of institutional collapse. The highly anticipated “passport to the future” envisioned by the complex mission-oriented policy fell short. An unstable institutional framework coupled with government-driven personalistic maneuvers further exacerbated institutional instability.

In retrospect, the primary policy efforts focused on macroeconomic and institutional conditions rather than addressing the balance between macro- and micro-challenges. There was a relative lack of focused policies and programs aimed at developing strong technological and organizational capabilities. While markets were created through institutional and fiscal incentives, and local content policies reserved market shares, the complexity of mastering shipbuilding capabilities within the suddenly limited window of opportunity was underestimated by public authorities.

Concluding Remarks

Mission-oriented policies (MOPs) have primarily aimed to stimulate market creation and foster innovation (Mazzucato 2013). However, as Morris (1980) noted, good policy intentions often come at a high cost. While “new” MOPs emphasize the state’s role in directing change to tackle grand environmental and societal grand challenges, the Brazilian shipbuilding case brings insights into the difficulties associated with governmental efforts to market creation. Well-functioning markets rely on producers’ ability to meet the technical and economic requirements for delivering desired outcomes. The misalignment between policy intent and the real possibilities of market creation that considers the concrete availability of technological and organizational capabilities at any given time results in policy ambiguity that hinders the successful implementation of missions (Alves et al. 2021). Moreover, this unclear view of the gap between policy expectations and the technological and organizational requirements is riddled with uncertainty, leading to unanticipated costs.

Although the Brazilian shipbuilding mission-oriented policy exhibited important “success factors” outlined in the MOP literature – including a window of opportunity, ambitious technological goals, institutional incentives, significant public financing, extensive private sector investment and involvement, detailed planning, a sense of urgency, and social and national engagement (Mazzucato 2018), it failed to really create and sustain a market.

While in the short term, markets can be created through an active interventionist, real markets must be sustained in the long run through competitive transactions and technological innovation. A crucial requirement is matching current regional and national capabilities to be leveraged with those necessary for comparative and competitive advantage. The difficulty in quickly finding this balance can result in high costs and undermine the prospects of success. These costs encompass technology transfer, supplier switching, and dynamic transaction costs (Langlois 1992), which involve the efforts of persuading, negotiating, coordinating, and teaching others or simply the costs incurred by lacking necessary capabilities when needed.

Mission-oriented policies, through institutional frameworks (e.g., knowledge base, S&T system, business propensity and culture, supply chain, and regulation), may come as a tempting strategy in developing countries to escape the middle-income trap and build the foundations of viable markets. However, to fully capitalize on market entry incentives, latecomer economies must find faster and cost-effective ways to learn and develop capabilities or selectively choose specific packages that align with their technological levels and economic context.

Notes

- 1.

Lei 9.478/97 (Lei do Petróleo), Lei 12.351/10 (Lei da Partilha de Produção), Lei 12.304/10 (Lei da criação da PPSA), Lei 12.276/10 (Lei da Cessão Onerosa).

References

Abramovitz, M. (1986). Catching up, forging ahead, and falling behind. Journal of Economic History, 46(2), 385–406.

Aldieri, L., Sena, V., & Vinci, C. P. (2018). Domestic R&D spillovers and absorptive capacity: Some evidence for the US, Europe, and Japan. International Journal of Production Economics, 198(1), 38–49.

Alves, A. C. (2015). Industrial Organization Dynamics: Bounded Capabilities and Technological Interfaces of the Brazilian Shipbuilding and Offshore Industry. Doctoral Dissertation. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Alves, A. C., Vonortas, N. S., & Zawislak, P. A. (2021). Mission-oriented policy for innovation and the fuzzy boundary of market creation: The Brazilian shipbuilding case. Science and Public Policy, 48(1), 80–92.

Arrow, K. J. (1962), Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for R&D. In R. R. Nelson (Ed.), The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity: Economic and Social Factors (pp. 609–625). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Barat, J., Campos Neto, C. A. S., & Paula, J. M. P. (2014). Visão econômica da implantação da indústria naval no Brasil: Aprendendo com os erros do passado. In C. A. S. Campos Neto & F. M. Pompermayer (Eds.), Ressurgimento da Indústria Naval no Brasil (2000–2013) (pp. 31–68). Brasília: Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea).

Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2014). Inside the high-tech black box: A critique of technology entrepreneurship policy. Technovation, 34(12), 773–784.

Bush, V. (1945). Science: The Endless Frontier. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Campos Neto, C. A. S., & Pompermayer, F. M. (2014). Ressurgimento da indústria naval no Brasil 2000–2013. Brasilia: Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea).

Cho, D.-S., & Porter, M. E. (1986). Changing global industry leadership: The case of shipbuilding. In M. E. Porter (Ed.), Competition in Global Industries (pp. 539–568). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Cirera, X., & Maloney, W. F. (2017). The Innovation Paradox: Developing-Country Capabilities and the Unrealized Promise of Technological Catch-up. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Clarkson Research (2018). World Fleet Register. Clarkson Research Database. https://www.clarksons.net/wfr/

De Negri, J. A., & Lemos, M. B. (2011). O Núcleo Tecnológico da Indústria Brasileira. Brasília: Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea).

Edquist, C. (1997). Systems of Innovation. Technologies, Institutions, and Organizations. London: Printer.

Edquist, C., Vonortas, N. S., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M., & Edler, J. (2015). Public Procurement for Innovation. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Ergas, H. (1987). Does technology policy matter? In B. R. Guile & H. Brooks (Eds.), Technology and Global Industry: Companies and Nations in the World Economy (pp. 191–245). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Fisher, R., Chicot, J., Domini, A., Polt, W., Türk, A., Unger, M., Kuittinen, H., Arrilucea, E., van der Zee, F. A., Goetheer, J. D., & Lehenkari, J. (2018). Mission-Orientated Research and Innovation: Assessing the Impact of a Mission-Oriented Research and Innovation Approach. Final Report. Brussels: European Commission, DG Research and Innovation.

Foray, D. (2018). Smart specialization strategies as a case of mission-oriented policy—A case study on the emergence of new policy practices. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(5), 817–832.

Foster, M. G. (2013). Retomada da Indústria Naval e Offshore do Brasil 2003–2013–2020: Visão Petrobras. Rio de Janeiro: Petrobras.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Griffith, B. (2011). Middle-income trap. In R. Nallari, S. Yusuf, B. Griffith, & R. Bhattacharya (Eds.), Frontiers in Development Policy (pp. 39–43). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hodgson, G. M. (1988). Economics and Institutions: A Manifesto for a Modern Institutional Economics. Cambridge, MA and Philadelphia, PN: Polity Press and University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kim, L. (1980). Stages of development of industrial technology in a developing country: A model. Research Policy, 9(3), 254–277.

Kim, L., & Nelson, R. (2000). Technology, Learning, and Innovation: Experiences of Newly Industrializing Economies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Langlois, R. N. (1992). Transaction-cost economics in real-time. Industrial and Corporate Change, 1(1), 99–127.

Langlois, R. N., & Mowery, D. C. (1996), The federal government role in the development of the US software industry. In D. C. Mowery (Ed.), The International Computer Software Industry: A Comparative Study of Industry Evolution and Structure (pp. 53–85). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lee, K. (2013). Schumpeterian Analysis of Economic Catch-up: Knowledge, Path-Creation, and the Middle-Income Trap. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, K. (2019). The Art of Economic Catch-up: Barriers, Detours and Leapfrogging in Innovation Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, K., & Lim, C. (2001). Technological regimes, catching-up, and leapfrogging: Findings from the Korean industries. Research Policy, 30(3), 459–483.

Lee, K., & Malerba, F. (2017). Catch-up cycles and changes in industrial leadership: Windows of opportunity and responses of firms and countries in the evolution of sectoral systems. Research Policy, 6(2), 338–351.

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking the Public Vs. Private Myth in Risk and Innovation. London: Anthem Press.

Mazzucato, M. (2015). Innovation systems: From fixing market failures to creating markets. Intereconomics, 50(3), 120–155.

Mazzucato, M. (2018). Mission-Oriented innovation policies: Challenges and opportunities. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(5), 803–815.

Mazzucato, M., & Penna, C. (2015). Mission-Oriented Finance for Innovation: New Ideas for Investment-Led Growth. London and New York, NY: Policy Network and Rowman & Littlefield International.

Mazzucato, M., & Penna, C. (2016). The Brazilian Innovation System: A Mission-Oriented Policy Proposal. Report for the Brazilian Government Commissioned by the Brazilian Ministry for Science, Technology, and Innovation through the Centre for Strategic Management and Studies, (06/04/2016). https://www.cgee.org.br/the-brazilian-innovation-system.

McKelvey, M., & Saemundsson, R. J. (2018). An evolutionary model of innovation policy: Conceptualizing the growth of knowledge in innovation policy as an evolution of policy alternatives. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(5), 851–865.

Mises, L. von (1949). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Fox & Wickles.

Monteverde, K., & Teece, D. (1982). Supplier switching costs and vertical integration in the automobile industry. Bell Journal of Economics, 13(1), 206–213.

Morris, C. R. (1980). The Cost of Good Intentions: New York City and the Liberal Experiment, 1960–1975. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Mowery, D. C. (2010). Military R&D and innovation. In B. H. Hall & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Volume 2 (pp. 1219–1256). Amsterdam and New York, NY: North-Holland.

Nelson, R. R. (1995). Recent evolutionary theorizing about economic change. Journal of Economic Literature, 33(1), 48–90.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1977). In search of useful theory of innovation. Research Policy, 6(1) 36–76.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

North, D. С. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

Orlando, M. J. (2004). Measuring spillovers from industrial R&D: On the importance of geographic and technological proximity. Rand Journal of Economics, 35(4), 777–786.

Penrose, E. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. New York, NY: Blackwell Publishing.

Pires, F. C. M. Jr., Estefen, S. F., & Nassi, D. C. (2007). Benchmarking internacional para indicadores de desempenho na construção naval. Rio de Janeiro: COPPE/UFRJ.

Pisano, G. P., & Shih, W. C. (2012). Producing Prosperity: Why America Needs a Manufacturing Renaissance. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Polanyi, K., & MacIver, R. M. (1957). The Great Transformation. Volume 5. Boston: Beacon Press.

Richardson, G. B. (1972). The organization of industry. Economic Journal, 82(327), 883–896.

Rip, A., & Kemp, R. (1998). Technological change. Human Choice and Climate Change, 2(2), 327–399.

Rodrik, D. (2009). Industrial policy: Don’t ask why, ask how. Middle East Development Journal, 1(1), 1–29.

Rosenberg, N. (1990). Why do firms do basic research (with their own money)? Research Policy, 19(2), 168–174.

SINAVAL (2014). Information for candidates in the 2014 elections. http://sinaval.org.br/wp-content/uploads/Info-Candidates-2014.pdf

SINAVAL (2018). Agenda do SINVAL para as Eleições de 2018. http://sinaval.org.br/wp-content/uploads/Agenda-do-SINAVAL-Eleições-2018.pdf

Soete, L., & Arundel, A. (1995). European innovation policy for environmentally sustainable development: Application of a systems model of technical change. Journal of European Public Policy, 2(2), 285–315.

Teece, D. J. (1977). Technology transfer by multinational firms: The resource cost of transferring technological know-how. Economic Journal, 87(346), 242–261.

Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), 285–305.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York, NY: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (2009). Transaction cost economics: The natural progression. Nobel Prize Lecture, December 8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Alves, A.C. (2024). The Cost of Missions: Lessons from Brazilian Shipbuilding. In: Henrekson, M., Sandström, C., Stenkula, M. (eds) Moonshots and the New Industrial Policy. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 56. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49196-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49196-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-49195-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-49196-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)