Abstract

In this chapter, we use the Children’s Worlds database to investigate how ICT affects children’s subjective well-being in Europe, and whether its use crowds out other activities, which could have an impact on how satisfied children are with their own lives. The survey queries 8-, 10-, and 12-year-old children regarding their daily routine and activities, use of time, and the extent to which they agree with several statements. The questionnaire also includes information on their social, economic, and demographic background and, most importantly for our research, their self-assessed well-being and thoughts on ICT usage. First, we find that a higher frequency of playing electronic games, using social media, and having Internet access and/or a mobile phone is positively associated with overall subjective well-being. Second, we find no evidence of any crowd-out effects—that is children who spend more time with digital devices do not report that they devote any less time to other activities. Finally, we document the fact that the use of digital technologies is positively related to satisfaction with the amount of free time they have and with their use of time. These results are generally not consistent with the main takeaways from causal studies which highlight the importance of further research on this area.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Information and communications technologies (ICT)

- Subjective well-being

- Children’s Worlds database

- Crowd-out

- Electronic games

- Social media

- Internet access

- Life satisfaction

- Time satisfaction

- Use of time

Introduction

In recent decades, technology has been gaining in importance across the world. Children and young people are today growing up in a closely connected world, surrounded by digital devices. In fact, according to the European Union—Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), in 2019, about 97% of the European Union’s households have Internet access and about 96% of them have access to a computer.Footnote 1 However, not all children benefit equally from online experiences, which is referred to as the ‘third-level’ digital divide (van Deursen & Helsper, 2015).Footnote 2 Consequently, research on digital exclusion has shifted its focus from merely examining Internet access, skills, and usage (‘first- and second-level’ digital divide) to exploring tangible outcomes (e.g. using the Internet to search for employment opportunities could increase the likelihood of finding a better job). Van Deursen and Helsper (2015) acknowledge the complex relationship between Internet usage and other types of advantages or disadvantages. However, they point out that there is a deficiency of established measures to broadly comprehend which groups are prone to gain the most from Internet access. Research evidence shows that in Europe, on average 20% of 9–10-year-olds had negative experiences online in 2019, such as cyberbullying, and that 8–17% of 9–16-year-olds encountered online harmful content (Smahel et al., 2020). In a comparative study covering seven European countries (Greece, Spain, Poland, Germany, Romania, the Netherlands, and Iceland), Tsitsika et al. (2014) explore the prevalence of which Internet addiction experienced among adolescents and find substantive variation across countries—ranging from 23% of adolescents in Spain to 8% in Iceland. The risks arising from digital technologies also include sleep, learning, and attention deficit problems, as well as breaches of privacy and confidentiality (Bruni et al., 2015; Livingstone et al., 2011). Nonetheless, the literature also documents the fact that digital technologies can offer the digital generation benefits in terms of health, socialization, knowledge, and, most importantly, well-being (Hamm et al., 2014; Chassiakos et al., 2016; Chiong & Shuler, 2010).

Here, we use the Children’s Worlds database (https://isciweb.org/) to investigate how ICT affects children’s subjective well-being in Europe, and whether its use crowds out other activities, which could have an impact on how satisfied children are with their own lives. The survey queries 8-, 10-, and 12-year-old children regarding their daily routine and activities, use of time, and the extent to which they agree with several statements. The questionnaire also includes information on their social, economic, and demographic background and, most importantly for our research, their self-assessed well-being and thoughts on ICT usage. Our analysis focuses exclusively on children aged 10 and 12 years living in Europe, who participated in the third wave of the survey—that is 32,179 children.

First, we find that a higher frequency of playing electronic games, using social media, and having Internet access and/or a mobile phone is positively associated with overall subjective well-being. Second, we find no evidence of any crowd-out effects—that is children who spend more time with digital devices do not report that they devote any less time to other activities. Finally, we document the fact that the use of digital technologies is positively related to satisfaction with the amount of free time they have and with their use of time.

The rest of this chapter is organized as follows. Section “Literature Review” reviews the existing literature on the connection between children’s outcomes and their access to and use of ICT. We devote particular attention to those studies that exploit some source of random variation to estimate causal effects. Section “Data” presents the Children’s Worlds database and discusses how we construct our working sample. Section “Results”, in which we provide the most important findings of this study, first analyses the association between ICT use and children’s overall subjective well-being; second, it explores whether ICT crowds out other activities of interest to children; and third, it examines the effect of the use of different new technologies on children’s satisfaction with their leisure time and with how they use their time. Section “Conclusions” includes a closing discussion and a conclusion.

Literature Review

ICT and Children’s Well-Being

Studies exploring the causal effects of new technologies on children’s well-being are relatively few and far between.Footnote 3 One exception is McDool et al. (2020), which investigates the extent to which access to faster broadband has had a causal impact on the way English children feel about different life domains. Like many studies in this strand of literature, the authors assume that broadband speed proxies Internet use. Using an instrumental variables (IV) estimation, the authors find that more intensive Internet use harms subjective well-being, particularly concerning children’s feelings about their appearance. However, they do not find any effect on how children feel about life as a whole.

In another study for the UK, McNamee et al. (2021) combine fixed effects and matching to find similar evidence for the prolonged use of social media: they show that using social media for more than four hours a day results in poorer emotional health and more behavioural difficulties among children. Moreover, they document the fact that the intensive use of social media is particularly harmful in terms of self-perception. However, their findings also suggest that limited use of social media (less than three hours a day) does not damage well-being and may even have a positive effect on socialization with friends—we discuss this finding below while reviewing the crowd-out effects of new technologies. Recent descriptive studies also seem to support the idea that children and adolescents who spend long periods on social networks tend to show lower levels of well-being and have a higher risk of suffering depressive symptoms (cf. Frith, 2017; Gunnell et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2018; Woods & Scott, 2016). Intensive use of social media in early adolescence is also associated with lower levels of well-being in later adolescence, particularly among females (Booker et al., 2018).

Further evidence of the causal impact of social media on well-being comes from Braghieri et al. (2022), who studied how the staggered introduction of Facebook across US colleges in the mid-2000s affected the mental health of adolescents and young adults. They show that the roll-out of Facebook triggered a decline in the state of mental health of those college students exposed to it. Furthermore, the roll-out fostered the take-up of depression-related mental healthcare services and influenced the academic performance of students exposed to Facebook. The authors also shed some light on why social media might damage mental health: the main mechanism seems to be consistent with the idea that Facebook enhances people’s ability to engage in unfavourable social comparisons. Experimental evidence for adolescents and young women (Fardouly et al., 2015; Kleemans et al., 2018) and descriptive evidence for students (Chou & Edge, 2012; Tandoc Jr. et al., 2015) also support this explanation.

ICT and Crowd-Out Effects

In what follows, we cover the existing evidence on crowd-out effects. The ‘crowding-out’ hypothesis can help to explain why the extensive use of new technologies could hamper children’s well-being. This hypothesis suggests that intensive Internet use reduces the time children spend on other activities that are positively related to subjective well-being—for example the time they spend with their families or friends, or studying or enjoying non-digital entertainment.Footnote 4 Here, we provide an overview of the existing causal evidence of new technologies crowding out other activities pursued by children. We begin by discussing McDool et al. (2020), who provide a good introduction to the topic, as they discuss how new technologies affect a vast number of well-being domains. We then move to quasi-experimental studies exploring crowd-out effects on education, which is the well-being domain on which the bulk of the evidence on crowd-out effects concentrates. Finally, we round off this section by looking at the causal evidence on whether new technologies crowd out socialization among children.

McDool et al. (2020) investigate whether more intensive Internet use (proxied by broadband speed) has led children in England to sacrifice some of the time they devote to other activities. They find that, as Internet use increases, children on average feel worse about their schoolwork, their appearance, their friends, and the school they attend. The effects are particularly striking in terms of how children feel about their appearance and their schoolwork. In addition, more Internet use is found to crowd out face-to-face social interactions. In particular, more time spent online reduces the total number of activities that the child undertakes per week, including playing sports, engaging in face-to-face interaction with friends and family, doing extracurricular activities, going to organized events, or volunteering. They find no effect on how children feel about their families. These findings are generally consistent with those of earlier descriptive studies (cf. Helliwell & Huang, 2013; Moreno et al., 2013; Sabatini & Sarracino, 2018; Wallsten, 2013).

Several causal studies have explored whether the more intensive use of new technologies crowds out education and time spent doing homework. Suziedelyte (2015) tests the effect of electronic games on learning. She uses data from the Child Development Supplement of the US Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Her fixed-effect estimates suggest that, on average, gaming improved children’s ability to solve problems. It is, however, important to stress that the estimated effect decreases with the number of hours spent gaming. She also finds evidence of the complementarity between video games and other sources of learning, as the estimated effect is larger in families that invest more resources in children. Descriptive studies tend to show a positive relationship between heavy gaming and poor academic performance (Fiorini, 2010; Rideout et al., 2010).

Further evidence on this matter comes from the ‘one laptop per child’ programme run in various countries. Studies evaluating this intervention tend to show that it increases computer and Internet proficiency (Angrist & Lavy, 2002; Malamud & Pop-Eleches, 2011; Malamud et al., 2019; Mo et al., 2013). Evidence on student academic performance is, however, more mixed, especially in developing countries (cf. Angrist & Lavy, 2002; De Melo et al., 2014; Malamud et al., 2019; Mo et al., 2013). In Europe, Mora et al. (2018) combined fixed-effects estimation and matching and found a negative impact on language proficiency and mathematics among Spanish students. Similarly, Malamud and Pop-Eleches (2011) used a regression discontinuity design to evaluate the programme in Romania. They found that those students who just qualified to benefit from the programme had significantly lower grades at school than those who just failed to qualify. Moreover, they found that the computer voucher also led to a reduction in the time children spent doing homework and reading. As for the mechanisms behind these results, Vigdor et al. (2014) point out that access to home computers is associated with academic achievement only in households with more effective parental monitoring. The style of parental supervision could compromise some of the gains of the programme. Specifically, Malamud and Pop-Eleches (2011) showed that parental rules governing computer use limited any positive effects on computer skills without doing anything to improve academic performance. Finally, Malamud et al. (2019) also show that there is a pronounced drop in the use of subsidized computers over time and that the main category of computer use is entertainment.

We close this discussion of studies into the crowd-out effects of new technologies on education by reviewing existing causal evidence on the effect of Internet access on children’s educational achievement. Sanchis-Guarner et al. (2021) evaluate the effect of high-speed Internet at home on the national test scores of 14-year-old English students. Their results show that a 1 Mbit/s increase in the broadband speed raises test scores by 1.37 percentiles. They interpret this as the net effect of Internet speed on education and argue that the positive impact of higher Internet speed is felt in the form of greater productivity, better educational opportunities, and learning improvements, and that this more than compensates for the negative impact of unproductivity and distraction. Their study cannot, however, explain the mechanisms driving this positive relationship between broadband speed and better test grades.

Finally, a group of studies has looked at the crowd-out effects of new technologies on socialization. McNamee et al. (2021) find that limited use of social media has a positive effect on children’s socialization skills. In a large experimental study that subsidized home computers in the US, Fairlie and Kalil (2017) also found evidence pointing in the same direction. Their results show a slightly positive effect of computers on children’s social development: children in the treatment group were more likely to spend time on social media, but also in communicating and interacting with their friends in person.

Data

We use data from the third wave of the Children’s Worlds surveyFootnote 5 to explore how the use of ICT affects children’s subjective well-being in Europe and to see whether the use of ICT crowds out other activities. This could have an impact on how satisfied children are with their own lives. Children’s Worlds is an international survey designed to investigate children’s well-being, and its database covers 35 countries/federal regions across 4 continents in 3 separate waves (2011–12, 2013–14, and 2016–19). The survey asks children aged 8, 10, and 12 years questions about their daily lives and activities; their use of time; the extent to which they agree with several statements; their socio-demographic and economic characteristics; and—most importantly for the DigiGen project—their opinions about their well-being and the use of ICT. For more information on the questionnaire topics, please see Table 5 in the Appendix.

Our analysis is based solely on the third wave of the Children’s Worlds survey. There are several reasons behind that decision. First, it should be noted that the Children’s Worlds survey is not very well suited to exploring changes over time in how ICT affects children’s subjective well-being. Many of the questionnaire items regarding the use of ICT have altered from wave to wave: for instance, the second wave only asked children how frequently they spent time on a computer, whereas in the third wave, children were asked how often they spent time playing electronic games and using social media. Second, inconsistencies across waves also affect questions regarding time spent on other activities: our analysis requires such information, to allow us to explore crowd-out effects. The first and second waves, for example, did not ask children about the amount of time they spent with their family or friends. Finally, the pool of European country participants in the Children’s Worlds survey has also varied across the waves. Half of the European countries that have participated only joined in the third wave, while only three have been involved since the start. And so, we have restricted our analysis to the latest wave, which allows us to explore the relationship between ICT and children’s well-being using the most up-to-date information available.

In all waves, three separate questionnaires were used—one for each age group. This allows the questionnaires to be adapted to the child’s age. The questionnaires for children aged 10 and 12 are thus longer and more comprehensive than the one used for 8-year-olds. As well as their length, they also differ in the wording and format of the questions. For example, in the version for 8-year-olds, a scale that employs emoticons is used to gather information from children on their satisfaction and happiness items (Casas, n.d.). Finally, the different questionnaires also differ in terms of their rate of non-response: for instance, about half of all 8-year-olds failed to answer most of the questions regarding the use of ICT. We thus opted to focus our analysis on the two older cohorts—children aged 10 and 12. Other studies that have used the Children’s Worlds survey have also followed this approach (cf. Savahl et al., 2021).

It is worth noting that, in many of the participating countries, the results are not representative of the entire national territory, as the surveys are only conducted in specific regions. Table 6 in the Appendix shows the participation of countries/federal regions, as well as the number of children surveyed in each wave.

Thus, our final sample includes those children aged 10 and 12 years who were living in Europe and who participated in the third wave—that is 32,179 children.Footnote 6 Table 1 presents our sample summary statistics. As indicated, 49.9% of the sample were boys. Regarding access to the Internet and technological devices, 96.7% and 84.7% of all those questioned reported having Internet at home and their mobile phone, respectively. Moreover, 65.1% had more than two computers at home, while 32.9% had one or two and 2% had none; 88.6% were living in a household with one or two bathrooms; and 6.7% said their families lacked a car. Regarding children’s use of time, 35.9% played electronic games every day and 45.5% used social media daily; 10.4% stated that they never spent time relaxing, talking, or having fun with their family, and 25.4% said that they never saw their friends outside school. Only 24.4% helped around the house each day, while 26.4% practised sports daily.

In terms of subjective well-being, the questionnaire included a single question regarding overall life satisfaction (OLS): ‘How satisfied are you with your life as a whole?’ Children could answer from ‘0’ (not at all satisfied) to ‘10’ (totally satisfied). Such a measure of life satisfaction is often used as a proxy for the overall concept of children’s subjective well-being (Savahl et al., 2021). Many large-scale surveys, such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), include OLS measures in their questionnaires. The recent psychometric literature, however, considers children’s subjective well-being to be a three-dimensional concept that is better captured through multiple-item scales measuring the different components of subjective well-being (Casas, 2017; Savahl et al., 2021).Footnote 7 The third wave of the Children’s Worlds survey allows researchers to build such multiple-item scales, and we thus include them later on in our analysis. In our sample, 80.8% of children reported being ‘almost totally’ or ‘totally’ satisfied with their lives (9 or 10 on the OLS measure).

We proceed by computing an index of ICT use that summarizes the use of new technologies. We obtain this index by applying a principal component analysis (PCA) technique.Footnote 8 In our application, we take the four variables that refer to the use of new technologies (i.e. how often the child plays electronic games; how often she uses social media; whether she owns a mobile phone; and whether she has access to the Internet) and apply principal components. We keep the first component, which explains most of the information.Footnote 9 We transform the obtained component into a categorical variable, which increases in line with the use of ICT. As Table 1 shows, 4.4% of the children had a very low or low score on the ICT use index. All children in this category lacked a mobile phone and Internet access, and the vast majority of them never spent time playing computer games or using social media. Note also from Table 1 that most of the children have high ICT use scores: 83.5% had either a high or a very high ICT use index. This is consistent with the descriptive statistics for each new technology.

Results

In this section, we present the most important findings of our analysis. As mentioned above, our results refer to children in the second (aged 10) and third (aged 12) cohorts. First, we discuss our findings regarding children’s overall subjective well-being by showing how this indicator varies across European countries. We then move on to discuss our results in terms of the association between the use of new technological devices and OLS, devoting special attention to exploring this relationship across European country clusters.Footnote 10 Second, we look at whether the use of ICT crowds out other activities that could potentially bring children greater life satisfaction. Finally, we close the section by examining the effect of the use of different new technologies on children’s satisfaction with the amount of free time they have and their use of time.

Children’s Use of New Technologies and Overall Subjective Well-being

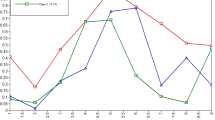

Figure 1 shows the overall levels of subjective well-being across the European countries in our sample. As the graph shows, children tend to report very high levels of overall life satisfaction throughout Europe. The average value for the set of countries covered by the database is 9.13. More interestingly, Fig. 2 shows the percentage of children who report low overall life satisfaction—that is an OLS score of below five. In the UK, 6.74% of children say they have low levels of life satisfaction, whereas in Greece the figure is 0.48%. Poland, Finland, France, and Estonia have percentages of around 3%; Malta, Hungary, Croatia, Italy, and Germany—of around 2%. In Spain and Romania, the proportion is relatively small: almost all children report medium–high levels of overall life satisfaction.

In what follows, we discuss our findings concerning the association between the use of new technologies and OLS. In particular, the results are the outcome of a series of linear regressions, where standardized overall satisfaction with life is regressed against the index of ICT use, and then on each new technology. Standard errors are clustered at the school level. The effect of new technologies on other indicators of subjective well-being is provided in Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10 in the Appendix.

As Table 2 shows, we first include a baseline specification that only considers country and questionnaire fixed effects. We then add a set of covariates that seek to control for the gender and the socio-economic background of the child (which might confound the effect of ICT use on well-being), such as the number of bathrooms, cars, and computers (as reported by the children themselves). We start by discussing the overall effect of ICT use on OLS for children, which is shown in the first two columns of Table 2. For the ICT use index, we find that higher frequencies of ICT use are positively associated with overall well-being. In particular, we find that as children use new technologies more often, so their overall well-being increases vis-à-vis those who have very low ICT use scores.Footnote 11 For the ICT use index, this is illustrated in the second column, which expands the specification by controlling for socio-economic background. Once we include controls in the regression, the estimated association decreases by around 15%. This is because, in our application, socio-economic indicators are positively correlated with both the outcome and the variable of interest. It is noteworthy that the shape of the association remains, even when we introduce the socio-economic variables as controls.

In the remaining four columns of Table 2, we explore the effect of each technology on OLS. All the models include country and questionnaire fixed effects and control for the gender and the socio-economic background of the child. For both time spent playing electronic games and time spent on social media, we find that higher frequencies of use are positively associated with overall well-being, with diminishing returns for daily users. Well-being seems to peak at five or six occasions per week when overall satisfaction with life is about 0.096 (0.117) standard deviations higher than among children who never play electronic games (use social media). Daily users do, however, report the lowest levels of overall well-being.Footnote 12 The last two columns of Table 2 provide the effect of the other two indicators on new technologies present in the Children’s Worlds survey: (1) having a mobile phone and (2) having Internet access at home. Note that for these two indicators, the database registers not the time spent using the item, but whether or not the children have the item. We find that owning a mobile phone or having Internet access is positively associated with children’s overall well-being. In particular, children who have a mobile phone have, on average, OLS scores that are 0.068 standard deviations higher than children who do not have such a device. In a similar vein, having access to the Internet at home is associated with quite a substantial increase in children’s well-being, of about 0.380 standard deviations. The effect found for each new technology is consistent with other indicators of subjective well-being—see Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10 in the Appendix.

We close this section by exploring the relationship between the ICT use index and OLS across European clusters (see Fig. 3). Both the Eastern and Baltic and the Northern and Continental European country clusters show a stronger relationship between the use of ICT and overall subjective well-being. In these two clusters, about 15% of those children who have very low ICT use scores report being ‘very dissatisfied’ or ‘dissatisfied’ with life in general. Conversely, in these two clusters, more than 95% of those children with very high ICT use scores report being ‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ with life in general. For Southern European countries, however, there is a less pronounced association between the use of new technologies and overall subjective well-being for children, driven by the composition of subjective well-being on the lowest levels of ICT use (see Fig. 3). In particular, while children in the Southern European cluster who have very high or high ICT use scores tend to show levels of subjective well-being that are consistent with those from the Eastern and Baltic and the Northern and Continental European countries, a different picture emerges for low and very low ICT users. In the Southern European cluster, only 5.12% of those children with very low ICT use scores report being very dissatisfied or dissatisfied with life in general. In other words, among children with very low ICT use, the proportion of those in the Southern European countries with poor subjective well-being is only a third of the figure for the Eastern and Baltic and the Northern and Continental European countries. Finally, the UK shows a distinct path in the relationship between the ICT use index and OLS. Specifically, children in the UK with very high ICT use report being less satisfied with life in general than do those with medium ICT use scores.

Does Children’s ICT Use Crowd Out Other Activities?

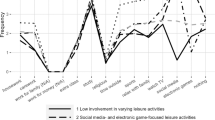

In this section, we explore whether the use of new technologies crowds out other activities. The results are obtained by regressing each activity, such as time spent relaxing with family members or seeing friends, on the ICT use index. A negative association between the greater use of new technology and time allocated to other activities would provide evidence of crowd-out effects. To keep the discussion concise, all the results provided below already account for the set of covariates considered in previous tables. Standard errors are clustered at the school level. The crowd-out effects of each separate technology are available in Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14 in the Appendix.

Table 3 provides the main findings. In general, they refute the hypothesis of substitution effects: there is no evidence that children who use ICT more intensively spend less time on other activities. In the case of both time spent relaxing, talking, or having fun with the family and time spent seeing friends, we find a significantly positive association: the more intensive their use of new technologies, the more time children spend with their family or seeing friends. This would suggest that there are no crowd-out effects on these activities. Moreover, it should be noted that heavy users of ICT report allocating considerably more time to their families and friends than those who have very low ICT use scores.Footnote 13 A similar (yet weaker) pattern is observed for time spent playing sports or doing exercise. As for time spent doing homework, there seems to be no difference across the various levels of electronic game use. Finally, the estimated coefficients for time spent helping around the house are not statistically significant. These patterns are generally consistent with that obtained by considering each technology separately in Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14. One exception worth mentioning is that we do find evidence of crowd-out effects on helping around the house among children who play computer games every day.

Children’s ICT Use and Satisfaction with Their Free Time and Their Use of Time

We now explore how using different new technologies influences children’s satisfaction with the amount of free time they have and with the way they use their time. The findings are shown in Table 4, where we look at the effect of the index of ICT use on each outcome. All the models include controls. In the first model, we observe that using new technologies is positively associated with being satisfied with how much free time one has: children who, on average, use new technologies more often are more satisfied with how much free time they have. That would imply that children enjoy using ICT in their free time. This association also holds across each of the ICT use levels. The largest associations are found for having access to the Internet and playing electronic games. Conversely, the effect of owning a mobile phone on children’s satisfaction with their level of free time is fairly small (results available in Table 15 in the Appendix).

The second model in Table 4 shows the effect of using new technologies on children’s satisfaction with how they use their time. We find that higher levels of ICT use are also positively associated with children’s satisfaction with their use of time. Note, however, that the effect of the ICT intensity index on children’s satisfaction with their use of time is relatively weaker than the effect on their satisfaction with the level of free time. This pattern is consistent with the effects found for each new technology, which also show that greater intensity of use or access to ICT devices is associated with higher levels of satisfaction with the use of time—see Table 15. Caveats remain in terms of the causal interpretation of the coefficients reported.

Conclusions

Here, we use the database covering the third wave of the Children’s Worlds survey to investigate how the use of ICT affects children’s subjective well-being in Europe; whether the use of ICT crowds out other activities; and how the use of such technologies affects children’s satisfaction with how much free time they have and with their use of time. First, we find that there is a positive association between the use of new technologies and children’s well-being: the more frequently children use new technologies, the greater the increase in their overall well-being. We also find that this association holds across different technologies and in all European clusters. Second, we find no evidence of crowd-out effects: those children who spend more time using digital devices do not report devoting less time to other activities. And finally, we show that ICT is positively related to satisfaction among children with the amount of free time they have, as well as with their use of time.

It is quite challenging to discuss whether these results are aligned with those from causal studies since there are some important methodological differences between our study and the current literature. First and foremost, our database directly asks children about their subjective well-being. This stands in sharp contrast to most of the causal studies reviewed. Hence, we are studying a dimension of children’s well-being for which there is no direct well-defined reference point. Second, when studying crowd-out effects, asking children directly might raise questions about whether children are consistent in terms of their time organization. Third, our intensity measures of ICT use are not very granular. That is, asking children how many days a week they play electronic games or use social media might not be enough to detect excessive use of new technologies. For instance, a child might well play computer games every day, but only for a short period.

Bearing these caveats in mind, the first two findings of this study are generally not consistent with the main takeaways from the causal studies reviewed. We believe that it is not possible to assess the validity of our third result based on existing causal studies. We start with our first finding. Only McDool et al. (2020) have explored the impact of new technologies on overall subjective well-being. Their study shows that more Internet use does not affect overall subjective well-being. Although we do not have a measure of Internet intensity use, their results would indirectly invalidate ours, since Internet use ultimately relates to social media and some forms of gaming. Second, most of the existing causal studies covered tend to contradict our findings on crowd-out effects. One exception is Sanchis-Guarner et al. (2021), who find that better Internet access has a positive impact on test scores. As for time spent with family, with friends, or playing sports, however, the existing causal studies tend to show that new technologies do substitute for such activities. McDool et al. (2020), for instance, show that more intensive Internet use reduces the total number of activities that the child undertakes per week, including the three mentioned above. This would run counter to the results of our study. One possible explanation could be that our intensity measure is not very granular, as already stated. Indeed, McNamee et al. (2021) find that the crowd-out effect of social media on time spent with friends depends on how intensively children use social media. Finally, for the crowd-out effect on education, McDool et al. (2020) also find that as Internet use increases, children tend to feel, on average, worse about their schoolwork and the school they attend. Their study also reports that more time spent on the Internet reduces the time children spend on extracurricular activities, which thus affects the positive spillovers for learning that children are thought to experience from such activities. Again, the time devoted to new technologies would seem to be a key factor in whether education is crowded out. Suziedelyte (2015), for instance, finds that a moderate amount of time spent playing video games improves children’s problem-solving abilities. Similarly, causal studies assessing the ‘one laptop per child’ programme point to parental supervision and the time limits placed on the use of new technologies as key drivers in overcoming poorer educational performance.

Notes

- 1.

Yet, it must also be acknowledged that, in 2019, 5.4% of children in Europe lived in a household that could not afford a computer and/or lived with adults who could not afford internet access (Ayllón et al., 2023).

- 2.

The literature on the digital divide encompasses three different levels: the ‘first-level’ digital divide is regarded as a binary classification of physical access (or lack thereof) to digital devices; the ‘second-level’ digital divide includes digital competencies and use; and the ‘third-level’ digital divide focuses on digital outcomes (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019; Hargittai, 2002; Ronchi & Robinson, 2019; van Deursen & Helsper, 2015).

- 3.

In contrast, there is a large body of observational studies that examines the relationship between new technologies and children’s well-being (see, for instance, Orben & Przybylski, 2019a, 2019b). Readers interested in exploring this research further are referred to a recent meta-analysis by Livingstone et al. (2021).

- 4.

In media and communication studies, this is often referred to as the ‘social displacement hypothesis’ (see, for instance, Valkenburg & Peter, 2007).

- 5.

For more information, visit: https://isciweb.org/

- 6.

The list of countries that our sample includes is as follows: Belgium (Flanders), Croatia, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy (Liguria), Malta, Poland, Romania, Spain (Catalonia) and the United Kingdom (England and Wales). We indicate in parentheses if the results come from only part of a country.

- 7.

This literature has operationalized children’s subjective well-being based on three main components (Diener et al., 1999). The first two refer to cognitive aspects of life satisfaction. Context-free life satisfaction is the first of these cognitive components, and includes aspects such as satisfaction with life as a whole. Definitions of domain-based life satisfaction instead capture other aspects of life satisfaction that are more domain specific, such as satisfaction with the people one lives with, or safety in the area where one lives. The last component is affective in nature and measures positive and negative affects, as, for example, how often a child feels happy or stressed. While our results in the main text refer to overall satisfaction with life, all the results regarding the rest of the definitions can be found in Appendices A2 and A3.

- 8.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a powerful statistical technique developed to summarize the most important features and relations of several variables. PCA reduces the dimensionality of the original dataset by computing a new set of variables, the principal components, as a linear combination of the original variables, ordered in terms of variance. In other words, PCA rearranges our variables in an information-equivalent, but more convenient, layout, where the variables are sorted according to the amount of information they can explain. For the interested reader, our implementation of PCA takes advantage of the ordinal structure of the variables we seek to summarize (see Kolenikov & Angeles, 2009).

- 9.

The correlation between the ICT use index and each new technology is remarkably high.

- 10.

Since we lack data from several European countries, we consider four relatively large country clusters: Southern European countries (Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain), Eastern and Baltic European countries (Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Poland and Romania), Northern and Continental European countries (Belgium, Finland, France and Germany) and the UK.

- 11.

These results should be treated with caution, however, as in no way can they be interpreted as causal, given that we cannot control for other unobserved factors that might affect the true effect of ICT use on children’s well-being.

- 12.

Even though the point estimate is smaller among daily users, differences with the rest of the categories are not statistically significant in the case of electronic games, while most are in the case of social media use.

- 13.

This pattern aligns with the Matthew effect or the amplification model observed in the digital divide literature. This phenomenon implies that those who are already socially connected and have access to digital technologies are more likely to benefit from them, while those who are socially isolated may become further marginalized without access to such resources.

References

Angrist, J., & Lavy, V. (2002). New evidence on classroom computers and pupil learning. The Economic Journal, 112(482), 735–765.

Ayllón, S., Holmarsdottir, H. B., & Lado, S. (2023). Digitally deprived children in Europe. Child Indicators Research, 16, 1315–1339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-10006-w

Booker, C. L., Kelly, Y. J., & Sacker, A. (2018). Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10–15 year olds in the UK. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–12.

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social media and mental health. American Economic Review, 112(11), 3660–3693. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20211218

Bruni, O., Sette, S., Fontanesi, L., Baiocco, R., Laghi, F., & Baumgartner, E. (2015). Technology use and sleep quality in preadolescence and adolescence. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(12), 1433–1441.

Casas, F. (2017). Analysing the comparability of 3 multi-item subjective well-being psychometric scales among 15 countries using samples of 10 and 12-year-olds. Child Indicators Research, 10(2), 297–330.

Casas, F. (n.d.). Objectives and methods of the Children’s Worlds project. https://isciweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Session1-ChildrensWorlds.pdf

Chassiakos, Y. L. R., Radesky, J., Christakis, D., Moreno, M. A., & Cross, C. (2016). Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics, 138(5), e20162593.

Children’s Worlds. (n.d.). International survey on children’s well-being. https://isciweb.org/

Chiong, C., & Shuler, C. (2010). Learning: Is there an app for that? Investigations of young children’s usage and learning with mobile devices and apps. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Chou, H. T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121.

De Melo, G., Machado, A., & Miranda, A. (2014). The impact of a one laptop per child program on learning: Evidence from Uruguay. IZA Discussion Paper No. 8489, Institute of Labor Economics. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2505351.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

Eurostat. (2019). Households – Level of internet access. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_ci_in_h&lang=en

Eurostat. (2022). Being young in Europe today – Digital world. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Being_young_in_Europe_today_-_digital_world&oldid=528990

Fairlie, R. W., & Kalil, A. (2017). The effects of computers on children’s social development and school participation: Evidence from a randomized control experiment. Economics of Education Review, 57, 10–19.

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38–45.

Fiorini, M. (2010). The effect of home computer use on children’s cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Economics of Education Review, 29(1), 55–72.

Frith, E. (2017). Social Media and Children’s Mental Health: A review of the evidence. Education Policy Institute.

Gunnell, D., Kidger, J., & Elvidge, H. (2018). Adolescent mental health in crisis. British Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2608

Hamm, M. P., Shulhan, J., Williams, G., Milne, A., Scott, S. D., & Hartling, L. (2014). A systematic review of the use and effectiveness of social media in child health. BMC Pediatrics, 14(1), 1–15.

Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills. First Monday, 7(4).

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2013). Comparing the happiness effects of real and on-line friends. PLoS One, 8(9), 1–17.

Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C., & Sacker, A. (2018). Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine, 6, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.12.005

Kleemans, M., Daalmans, S., Carbaat, I., & Anschütz, D. (2018). Picture perfect: The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychology, 21(1), 93–110.

Kolenikov, S., & Angeles, G. (2009). Socioeconomic status measurement with discrete proxy variables: Is principal component analysis a reliable answer? Review of Income and Wealth, 55(1), 128–165.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: The perspective of European children: Full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9–16-year-olds and their parents in 25 countries. EU Kids Online. https://www2.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/research/research-projects/eu-kids-online

Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2021). The outcomes of gaining digital skills for young people’s lives and wellbeing: A systematic evidence review. New Media and Society, 25(5), 1176–1202. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211043189

Lorenz, T., & Kapella, O. (2020). Children’s ICT use and its impact on family life. DigiGen Working Paper Series No. 1.

Malamud, O., & Pop-Eleches, C. (2011). Home computer use and the development of human capital. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(2), 987–1027.

Malamud, O., Cueto, S., Cristia, J., & Beuermann, D. W. (2019). Do children benefit from internet access? Experimental evidence from Peru. Journal of Development Economics, 138, 41–56.

McDool, E., Powell, P., Roberts, J., & Taylor, K. (2020). The internet and children’s psychological well-being. Journal of Health Economics, 69(102), 274.

McNamee, P., Mendolia, S., & Yerokhin, O. (2021). Social media use and emotional and behavioural outcomes in adolescence: Evidence from British longitudinal data. Economics and Human Biology, 41(100), 992.

Mo, D., Swinnen, J., Zhang, L., Yi, H., Qu, Q., Boswell, M., & Rozelle, S. (2013). Can one-to-one computing narrow the digital divide and the educational gap in China? The case of Beijing migrant schools. World Development, 46, 14–29.

Mora, T., Escardíbul, J. O., & Di Pietro, G. (2018). Computers and students’ achievement: An analysis of the One Laptop per Child program in Catalonia. International Journal of Educational Research, 92, 145–157.

Moreno, M. A., Jelenchick, L. A., Koff, R., Eickhoff, J. C., Goniu, N., Davis, A., & Christakis, D. A. (2013). Associations between internet use and fitness among college students: An experience sampling approach. Journal of Interaction Science, 1(1), 1–8.

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019a). Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: Evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychological Science, 30(5), 682–696.

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019b). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behavior, 3, 173–182.

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds, Menlo Park. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Ronchi, E., & Robinson, L. (2019). Educating 21st century children: Emotional well-being in the digital age. OECD Publishing.

Sabatini, F., & Sarracino, F. (2018). Keeping up with the e-Joneses: Do online social networks raise social comparisons? Economics Discussion Paper No. 2018-43.

Sanchis-Guarner, R., Montalbán, J., & Weinhardt, F. (2021). Home broadband and human capital formation. CESifo Working Paper No. 8846.

Savahl, S., Casas, F., & Adams, S. (2021). The structure of children’s subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(650), 691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.650691

Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Olafsson, K. L., & Hasebrink, U. (2020) EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries, EU Kids Online. The London School of Economics and Political Science.

Suziedelyte, A. (2015). Media and human capital development: Can video game playing make you smarter? Economic Inquiry, 53(2), 1140–1155.

Tandoc, E. C., Jr., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is Facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146.

Tsitsika, A., Janikian, M., Schoenmakers, T. M., Tzavela, E. C., Olafsson, K., Wójcik, S., George Florian Macarie, G. F., Tzavara, C., The EU NET ADB Consortium, & Richardson, C. (2014). Internet addictive behavior in adolescence: A cross-sectional study in seven European countries. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(8), 528–535. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0382

Valkenburg, P., & Peter, J. (2007). Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1169–1182.

van Deursen, A. J., & Helsper, E. J. (2015). The third-level digital divide: Who benefits most from being online? In L. Robinson, S. R. Cotten, J. Schulz, T. M. Hale, & A. Williams (Eds.), Communication and information technologies annual (pp. 29–52). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2010). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media and Society, 13(6), 893–911.

van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2019). The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media and Society, 21(2), 354–375.

Vigdor, J. L., Ladd, H. F., & Martinez, E. (2014). Scaling the digital divide: Home computer technology and student achievement. Economic Inquiry, 52(3), 1103–1119.

Wallsten, S. (2013). What are we not doing when we’re online? NBER Working Paper No. 19549.

Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 41–49.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Data

Children’s Use of New Technologies and Overall Subjective Well-Being

Does Children’s ICT Use Crowd Out Other Activities?

Children’s ICT Use and Satisfaction with Their Free Time and Their Use of Time

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ayllón, S., Brugarolas, P., Lado, S. (2024). ICT Use and Children’s Self-reported Life Satisfaction. In: Holmarsdottir, H., Seland, I., Hyggen, C., Roth, M. (eds) Understanding The Everyday Digital Lives of Children and Young People. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46929-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46929-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-46928-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-46929-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)