Abstract

-

Building a strong connection with the target audience, by considering their concerns, priorities, experience and knowledge, is crucial for effective engagement of non-academics in climate change adaptation research.

-

Also important is tailoring the method of engagement to each audience and intended purpose; for example, creating visual representations of complex scientific data or undertaking co-creative art projects.

-

Considering appropriate and effective ways of measuring impact and benefit from the outset—perhaps co-developed with users—is key to quantifying the overall success of a climate service.

Lead Authors: Rachel Harcourt & Nick Hopkins-Bond

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

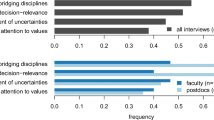

The UK Climate Resilience Programme (UKCR) aimed to deliver impact by responding to government priorities and opportunities, and by developing useful and usable research for end users. This book provides evidence of the wealth of outputs produced by the programme. Many UKCR projects also sought to achieve further impact by engaging directly with target audiences. The key learnings from the programme as to how best to do this are summarised in the infographic (Fig. 1) and explored further in the text below. The examples discussed are intended to be illustrative, rather than conclusive, to stimulate ideas and provide guidance for those planning research impact.

2 Ensure Regular Dialogue with End Users Throughout a Project to Ensure All Outputs Are Relevant and Usable

To achieve the key programme aim of developing policy relevant and usable outputs, researchers engaged in dialogue with central and local government partners to understand what ‘usable’ and ‘relevant’ means to them. For example, discussions with Bristol City Council as part of the ‘Meeting Urban User Needs’ project highlighted the need to make UK Climate Projections (UKCP18) data more easily digestible for a non-specialist. The council’s requirements were two-fold: to increase the use of UKCP18 in city-level adaptation planning and to create an output to help build risk awareness within the wider Bristol community. Establishing a key point of contact within the research team at an initial face-to-face meeting helped, as city stakeholders were hearing the ‘same voice’ throughout which nurtured trust. Regular light-touch follow-on meetings with users, interspersed with more in-depth conversations when required, created a continuous knowledge exchange. Through this process of co-development, the partnership produced the Bristol City Pack, an infographic style fact sheet combining simple messaging with an attractive style [1]. Based on feedback from Bristol City Council, this proved extremely successful in providing the required level of accessible and localised climate data. The ‘City Pack’ format has since been made available to 28 other UK cities with demand ongoing, plus requests for more detailed versions relating to a specific risk, such as heat related health risks in Manchester. This work has highlighted the importance of open dialogue to manage user expectations and communicate what is achievable with the resource and time available.

3 Develop a Detailed Timeline for Engagement and Dissemination Activities Capitalising on Periods of Heightened Subject Interest

When engaging government, it is essential to make use of moments of heightened policy focus. The five-year Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA), which is one of the central commitments of the UK 2008 Climate Change Act, receives significant media coverage upon publication. As well as detailing the latest understanding of UK climate risk, the CCRA sets out prioritisations for policy, directly informing the five-year National Adaptation Programme on how the government and others will prepare the UK for a changing climate. Its third iteration, CCRA3, was published in 2021 during the funding period of the UKCR programme, offering a significant opportunity for impact. UKCR researchers undertook a synthesis of UKCR-funded, peer-reviewed research to feed into the Technical Report [2] of the Independent Assessment Evidence Report for the CCRA3 [3]. Due to the protracted nature of the peer review process, it is noted that significant lead times are required to avoid the omission of relevant research from synthesis activities—particularly where it provides evidence for government policy. Factoring this into project timelines is key, and early conversations with publishers could result in special arrangements with regard to publication timescales.

4 Identify Ways of Measuring ‘Engagement’ and ‘Impact’ as Early in a Project as Possible

Both ‘engagement’ and ‘impact’ can be hard to define, quantify or provide evidence of, particularly during time limited research projects. Some UKCR projects addressed this by issuing feedback surveys and measuring website analytics, although these tend to measure participation rather than impact. Building solid relationships and maintaining dialogue throughout the project, as recommended elsewhere in this note, can facilitate the process of ongoing evaluation and learning. It is also possible to survey the collective impact of diffuse engagement efforts. For example, the UKCR-funded ‘RESIL-RISK’ project was a national survey of public perceptions of climate risks and adaptation. It found that UK residents are now much more aware of and concerned about the impacts of climate change and extreme weather events, particularly heat stress, in the UK compared with surveys taken only a few years ago. However, the survey did not investigate the likely multiple factors influencing this shift in public perception. Researchers, alongside project partners and intended audiences where possible, should agree success factors and measures of engagement and impact as the project plan is being developed. Although these may change as the project progresses, it is important that measuring impact should not be left to the end.

5 Summarise Findings into Bite-Size, Visually Appealing and Easily Relatable Formats

Usability of outputs was a key principle for the UKCR programme. Many policymakers and sector practitioners have no formal climate science training and often have little time to ingest complex climate change information; presentation is therefore vitally important and can be a barrier to impact, even if the information provided is relevant and needed. A UKCR project called ‘Communication of Uncertainty’ exploring non-experts’ responses to written and visual climate information, found that some factors facilitated understanding (e.g. use of colour, simple captions) while others hindered understanding (e.g. use of complex terminology and statistics) [4]. The research team used these findings to develop a set of ‘best practice’ design principles for communicating climate change information, which they summarised in best practice compliant infographics [4, 5]. The Met Office Communications and Knowledge Integration teams have adopted the guidance as standard practice when designing climate change communication materials, both for UKCR and more widely. The principles provide simple but useful guidance to climate science communicators using all mediums.

6 Build Solid Relationships with End Users to Help Disseminate Findings Directly to Target Audiences

There is a growing demand from many industries for information on current and future climate-related risks, effective adaptation strategies and climate services, driven by the reporting requirements of the UK Climate Change Act 2008, the UK government roadmap for mandatory adoption of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) [6], and ISO standards on adaptation to climate change [7]. One area of focus for UKCR was the UK agricultural sector, which is also responding to new legislation resulting from Brexit, changing expectations regarding land management and challenges due to climate change. This provided real opportunity for impact if UKCR researchers could develop and maintain relationships with those needing information to address this collection of issues. The ‘Multiple Hazards’ project looked at the risk of compound events (the combined effect of multiple hazards such as temperature and humidity) on the farming sector. From the outset, the research team engaged with government and farming agencies to understand key concerns and priorities, as well as to develop the outputs and types of communications needed. With parallels in many other industries, the relationships were built on the understanding that the agricultural partners brought unique knowledge of their land and experience of farming under variable weather. Building such relationships ‘opened doors’ to forums and spaces that resonated with the partner industry. In another example, the ‘CREWS-UK’ project developed a partnership with WineGB, the national association for the English and Welsh wine industry, which provided direct links and influence within the UK wine sector and ensured outputs were relevant to emerging sector priorities.

7 Adopt Creative and Community-Based Engagement Activities

Members of the public have essential roles to play in achieving increased national and local resilience by undertaking adaptive actions in their homes and daily routines, and by supporting adaptation initiatives from government and the private sector. However, climate resilience is a complex issue to communicate, and engaging people on what it means takes an emotional toll. While we are using ‘members of the public’ here for brevity, work by Climate Outreach [8] and others has shown that different sections of the UK public have very differing needs, interests and preferences. One means of addressing this is to bring creative climate communications into spaces where people already are. For example, the ‘Risky Cities’ project based in Hull drew the attention of city residents to local flood risks by exhibiting large-scale light and sound installations. In doing so, the project connected to its intended audience through the shared language of ‘Hull’ and used art to explore the city’s long history of living with water. In other examples, ‘Creative Climate Resilience’ worked with Manchester neighbourhoods to co-develop creative outputs that explored the temporal and geographical relevance of climate resilience to local communities, and another project, ‘Time and Tide’ conducted interactive performances on beaches and exhibitions in coastal communities. Researchers noted that these approaches can develop a sense of agency and ownership in the affected communities, while also bringing joyfulness and playfulness into a conversation which is often emotionally demanding. Chapters 3 and 6 provide further information on this topic.

References

Met Office. 2021. Bristol ‘City Pack’. [Online]. Available at: SPF City Pack_editable_template (ukclimateresilience.org).

Betts, R.A., Haward, A.B. and Pearson, K.V. (eds) 2021. The Third UK Climate Change Risk Assessment Technical Report. [Online]. Available at: Technical-Report-The-Third-Climate-Change-Risk-Assessment.pdf (ukclimaterisk.org).

Climate Change Committee. 2022. Independent Assessment of UK Climate Risk – Advice to Government for the UK’s third Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA3). [Online]. Available from: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/independent-assessment-of-uk-climate-risk/.

Kause, A., Bruine de Bruin, W., Fung, F., Taylor, A. and Lowe, J. 2020. Visualisations of projected rainfall change in the United Kingdom: An interview study about user perceptions. Sustainability 12(7), 2955.

Kause, A., Bruine de Bruin, W., Domingos, S., Mittal, N., Lowe, J. and Fung, F. 2021. Communications about uncertainty in scientific climate-related findings: a qualitative systemic review. Environmental Research Letters 16(5), 053005.

HM Treasury. 2020. A Roadmap towards mandatory climate-related disclosures. [Online]. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933783/FINAL_TCFD_ROADMAP.pdf.

International Organization for Standardization. 2021. ISO 14091:2021 Adaptation to climate change: Guidelines on vulnerability, impacts and risk assessment, Geneva: ISO.

Climate Outreach. The Seven Segments in Depth [Online]. Available from: https://climateoutreach.org/britain-talks-climate/seven-segments/.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following UKCR researchers for sharing their insights into delivering impact through their projects: Jenna Ashton, Richard Betts, Ed Brookes, Kate Gannon, Freya Garry, Helen Hanlon, Paul O’Hare, Claire Scannell and Corinna Wagner. Thanks also to George Burningham and Phoebe Wu for help with producing the infographic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Harcourt, R., Hopkins-Bond, N. (2024). Note on Delivering Impact. In: Dessai, S., Lonsdale, K., Lowe, J., Harcourt, R. (eds) Quantifying Climate Risk and Building Resilience in the UK. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39729-5_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39729-5_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-39728-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-39729-5

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)