Abstract

This chapter begins with a short presentation of the historical and biographical context of Bronfenbrenner’s research, which is followed by a description of his theory of an ecology of human development. This idea is presented both as a theory of child development and a theory of collaboration, as it is often the latter form that is applied in research on cooperation between early childhood education and care (ECEC) and parents/caregivers. The discussion addresses the ways in which Bronfenbrenner’s theory is currently applied in research on ECEC-family cooperation. In concluding remarks, the applications of the theory in relation to the understanding of more-than-parental involvement are presented in Chap. 1.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Short Context of the Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–2005), as a Jewish, Russian-born psychologist whose family escaped to the United States in his early years, acquired lived experience of how one’s societal surroundings can change the social trajectory of a family and the individuals that create it. After graduating from the developmental psychology department at Harvard, he started a PhD project at the University of Michigan, where his focus was on children’s development in the context of their peer groups. This relational and contextual focus on human development became the core thread of his further academic work and political activism. Bronfenbrenner was invited to the US Congress and a diverse array of governmental expert groups, where he managed to challenge the established view of biological/genetical determinism and provide American society with a wider, more contextual explanation of why the American Dream is not achieved by every individual, and how there are ecological reasons for why some children end up poor, homeless, or at risk of other adverse experiences. Reflection on the diverse developmental paths that arise as consequences of events happening in different settings directly impacting the child, as well as the interactions and relations between those settings within a broader context of socio-economy and cultural norms, brought Bronfenbrenner to develop the ecological model of environment “as a set of nested structures, each inside the next, like a set of Russian dolls” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 3). Among these “nested structures,” he underlined the roles of both the actors and settings that directly interact with the child (e.g., the family, pre-school, and peers), as well as the types of relationships that exist among these actors and settings.

Ecology of Nested Structures as a Theory of Human Development

Analogical to the cultural-historical wholeness approach presented in the first chapter, ecological systems theory highlights the social context and complexity of the relationships that contextualise and constitute a child’s life and development. The “set of nested structures, each inside the next” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 3) draws a model of bigger and bigger circles of influence surrounding the child. None of the systems (micro-, meso-, exo, etc.) operates in a vacuum, but is instead interconnected with all the others. In such an ecology (of nested structures), a human being becomes. The process of becoming entwines the individual and the social surroundings in a dialectics of accommodation. As Bronfenbrenner (1979) put it,

The ecology of human development involves the scientific study of the progressive, mutual accommodation between an active, growing human being and the changing properties of the immediate settings in which the developing person lives, as this process is affected by relations between these settings, and by the larger contexts within which the settings are embedded. (p. 21)

Bronfenbrenner also underlines how the larger contexts change over time, which again are interrelated with the child, her development, and the conditions that allow for it, as well as the (developmental) changes that happen over time in the child herself. All of these factors have their own impacts on the surroundings. It is thus possible to say that Bronfenbrenner (1975) focused on “how environments change, and the implications of this change for the human beings who live and grow in these environments” (p. 439).

The different ecological environments, “each inside the next,” are systematised by Bronfenbrenner in the following way:

-

The microsystem(s) includes the people and elements of the environment that have direct contact with the child (e.g., parents, siblings, teachers, ECE, school, and peers), who influence the child’s life, and whose lives may be changed/influenced through interacting with the child.

-

The mesosystem, also called the system of microsystems, is the system that encompasses the interactions between a child’s microsystems, referring directly to the collaboration between ECE and parents as the main microsystems of a young child’s life.

-

The exosystem relates to the larger formal and informal social structures that the child does not participate in directly, but that still have an impact on the child’s life, well-being, and development. This layer includes the parents’ workplaces and their schedules, networks, friendships, and so on.

-

The macrosystem is the general socio-cultural context that includes the legal framework, cultural values, customs, and principles. This layer also includes the infrastructure of ECE, as well as the diverse types of economic and social support for parents in different life situations.

-

The chronosystem includes both the timing and ageing of the life of the child and family, as well as historical changes in the socio-cultural environment.

The idea of looking at the child through her closest social surroundings and relationships (microsystems) was present in psychological research before Bronfenbrenner. However, his reach beyond the micro and mesosystem indicates his intent to seek less transparent connections and influences on the child’s life, “such as decisions made by the manager of a setting, the quality of the parents’ workplace, social media and informal social networks” (Halpenny et al., 2017, p. 16). These are included in the exosystem, which, in more indirect ways, shapes the everyday lives of a child and a parent. The length of parental leaves, the availability of ECEC services, and the existence of family networks, as well as parental working hours and the presence of neighbours and the local community, are the significant elements of the exosystem, which are again connected to the macrosystem with the power of its legal apparatus and redistribution of economic resources that enable or limit diverse solutions and interconnections in the life of a family and an ECEC setting.

What is important to highlight is that both the macrosystem and exosystem, as well as the mesosystem, microsystem, and the individuals participating in them, change over time. The time aspect is included in the chronosystem and shows how the appearance of a child’s daily life may have changed over time, and that the childhood of our grandparents was completely different than hours, both in terms of access to ECEC, toys, and technologies, but also in terms of the people we spent time with during the first years of our lives.

As this is a theory of human development, Bronfenbrenner places the child at the centre. This positioning is supposed to demonstrate that the child, to a great degree, is influenced by her context; however, it also highlights the child’s agency and potential influence. Such a model makes the child a subject and agent and not a passive “product” of her own surroundings, thus providing conditions for intellectual, emotional, social, and moral development:

A child requires participation in progressively more complex reciprocal activity on a regular basis over an extended period in the child’s life, with one or more persons with whom the child develops a strong, mutual, irrational, emotional attachment and who is committed to the child’s well-being and development, preferably for life. (Bronfenbrenner, 1991, p. 2)

This quote becomes the basis for the following famous phrase in Bronfenbrenner’s speeches: Every child needs at least one adult who is irrationally crazy about him or her. This irrationally crazy engagement shall also, however, characterise interconnections at the level of the mesosystem. This focus on the interconnections makes the ecological systems theory, a theory of collaboration that enables us to see and operationalise the “crazy engagement” of diverse institutions involved in the child’s life and in different socio-cultural settings, but which also enables us to spot the insufficient level of influence, leading to disadvantaged biographical paths.

Ecology of Child Development as a Theory of Collaboration: A Focus on Linkages

The “crazy engagement” of diverse institutional partners in the child’s well-being and well-becoming relates to the concept of linkages. Bronfenbrenner describes linkages as interactions between at least two actors from different microsystems, such as the family and the ECEC setting, or the ECEC setting and the future school of the child. The interactions are constitutive for the second level of influence at the mesosystem; however, their quality can differ, and not each of them can be characterised as a form of “crazy engagement.” Nevertheless, each will be interlocking and intermeshing the interacting partners. This means that the interactions in the mesosystem have a mutual influence on the practices in each of the interacting microsystems, which effectively makes the child’s transitions between the microsystems smoother.

The theory itself allows to capture all kinds of linkages and reflect on how the diverse actors and institutions involved in the child’s development can either strengthen or counteract each other’s influence, as well as how they can either strengthen or resist the effect of exo- and macrosystems on the child’s (well-)being and (well-)becoming. A mesosystem consisting of efficient inter-locked microsystems has indeed the potential to neutralise inequalities generated at the exo- and macrosystem in different ways.

Parental involvement is unmasked as a practice that strengthens the asymmetries and inequalities generated at the level of exo- and macro-systems in research showing the white middle-class premisses underlying the established expectations of parents in this context (Eliyahu-Levi, 2022; Sengonul, 2022; Uysal Bayrak et al., 2021). However, there are also examples of programmes that help families develop the competences and resources expected by educational institutions (Gedal Douglass et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2021) and create diverse arenas of involvement that are accessible to all parents. Another way of mitigating inequalities consists of opening up educational institutions to incorporate the families’ lingual, cultural, spiritual, and intergenerational resources and transforming institutional practices into ones more responsive to families’ cultures and needs (McKee et al., 2022; Warren & Locklear, 2021). This, in turn, allows the children/families to become resourceful participants who have a lot to share and can thus flourish (Ejuu & Opiyo, 2022). Nevertheless, just participation may require “equipping for inclusion” and “enabling access” before engagement and the negotiation of the terms of participation are even possible (Fenech & Skattebol, 2021).

Discussing Applications of Bronfenbrenner’s Theory – A Scoping Literature Review

Even though the theory of ecological systems can be related to the diverse linkages and collaborations between micro-, meso-, macro-, and exosystems, it is not guaranteed to be employed in this way. To identify the various applications of the theory, I conducted a scoping literature review of research on parental involvement in (early childhood) education that includes works on ecological systems theory published in the form of academic journal articles within the last 20 years (i.e., since 2002).

The review was initiated on the EBSCOhost Research Databases interface, through which the following databases were accessed: ERIC, Teacher Reference Centre, and Academic Search Elite. The key words:

-

+ Bronfenbrenner or ecological system*.

-

+ parent* or family* or mother* or father*.

-

+ involvement or engagement.

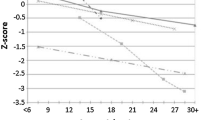

As presented in Fig. 4.1, the total number of hits was 26, three of which were duplicates and were removed from the search. Three of the papers turned to use Bronfenbrenner’s theory in children’s medicine and were excluded by me. All of the 20 included articles were retrieved and screened. During the first screening, it turned out that only 3 of the articles were related to ECEC. The other however were relevant for discussion on how the theory is applied. The 20 articles were then divided into 3 overlapping groups. The first applied the theory as a theory of child development (n = 11), the other as a theory of collaboration (n = 8), and the third comprised articles directly related to ECEC (n = 3).

Applying Bronfenbrenner’s Theory of Child Development

In 11 of the articles, ecological systems theory was applied as a theory of child development, with the intention of verifying more nuanced connections, linkages, and causalities that collaborations at the mesosystem can have on one or another aspect of a child’s development. The aim of finding more nuanced causalities led the authors to narrow the child’s development and operationalise it, for example, as academic outcomes (Day & Dotterer, 2018), academic achievement (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017), early language and literacy skills (Kim & Riley, 2021), risk/protective factors for bullying (Espelage, 2014; Hong & Espelage, 2012), bullying involvement (Hong et al., 2021), intrapersonal intelligence of girls (Sheoran et al., 2019a), musical intelligence (Sheoran et al., 2019b), mental health (Ziaei & Hammarström, 2021), mental health in war (Diab et al., 2018), and children’s music lives (Ilari et al., 2019). These diverse aspects of child development were presented as the focus of the research, with a connection being made to both the research gap in a particular academic field and Bronfenbrenner’s theory.

However, with the use of ecological systems theory, the way in which diverse studies conducted in different cultures and countries narrowed/operationalised child development is worthy of attention. The meanings, values, and rules of the exo- and macrosystems make different aspects of child development important, and worthy of academic focus, so that correlation between particular conditions for development and development of a particular ability/skills could be proven. These studies, however, did not use Bronfenbrenner’s theory to justify their own focus on a particular aspect of development, but to generally justify their search for the connection between a specific aspect of child development and a characteristic of a microsystem (Diab et al., 2018; Sheoran et al., 2019a, b), mesosystem (An & Hodge, 2013; Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017; Holt et al., 2008; Iruka et al., 2020; Keyes, 2002; McBrien, 2011), or macrosystem (Ziaei & Hammarström, 2021).

The potential blind spots in such applications of the theory lie in the narrow focus of these studies. These blind spots are not only in the operationalisations of the child’s development, but also in the choices of staying at the microsystem level. One can ask how ecological it is to relate one aspect of the development, such as interpersonal intelligence, musical intelligence of girls, and mental health in war, to parenting styles (Sheoran et al., 2019a, b), parents’ depressive symptoms, peer relations, or particular teacher practices (Diab et al., 2018) without realising the mesosystem in which all of the actors communicate, negotiate, and (dis)harmonise their influence on the children. An intriguing application of the Bronfenbrenner’s theory to challenge the established methodologies of measuring human development is presented by Koller et al. (2020). The authors create ecological engagement methodology that emphasizes the individual’s interactions with people, objects and symbols as crucial and measurable aspects of development.

Applying Ecological Systems as a Theory of Collaboration

When classifying the various implementations of Bronfenbrenner’s theory as a theory of collaboration, I used the criterion of active involvement based on the mesosystem perspective in the research. As the mesosystem is about relationships and partnerships between institutions constituting the child’s different microsystems, I chose research that embraced the relationship between two such institutions/organisations, which reduced the number of analysed articles to eight. This will say that articles such as the one of Kulik and Sadeh (2015) on fathers’ involvement in childcare as a phenomenon depending on the occupation and working hours of the mothers, rural/urban context of the family living, fathers’ experiences from own childhood and the child’s temperament were not included, as they focus on sharing the care task in the parental team (and not on partnerships between diverse institutions constituting the mesosystem). The included articles encompassed both home and an institutional settings of education/care involved in the child’s daily life. Even though the collaboration between the institutions was connected to the child, the analysed articles varied in ways they included the child perspective.

One article (Yngvesson & Garvis, 2021) included the child as a central subject and actor in the collaboration between home and pre-school. Other articles focused on particular activities undertaken by the mesosystem’s actors (Kim & Riley, 2021) or on the characteristics of the relationships between them (An & Hodge, 2013; Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017; Holt et al., 2008; Iruka et al., 2020; Keyes, 2002; McBrien, 2011), and the eventual influence of these relationships on the child’s development (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017; McBrien, 2011).

In trying to find more linkages mediating the (far too) simple causality between parental involvement and children’s academic outcomes, the researchers engaged with different nests of Bronfenbrenner’s model. Some invented and verified more variables at the mesosystem, such as parental satisfaction with the school, which turned out to mediate their involvement in it (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017). Others (McBrien, 2011) searched for explanations at the exo- and mesosystem levels when observing that the same parental strategies of getting involved with the school (e.g., school-based or home-based involvement) undertaken by parents representing diverse minorities led to different/opposite effects in children’s academic socialisation and thus academic outcomes.

In a study on very young children (Kim & Riley, 2021), the academic outcomes were adjusted to the developmental level of the child and interpreted as a base for future academic outcomes. Even though the focus on school performance is anchored in the culture and traditions of ECEC (Bennett, 2010), the study did not relate to the macrosystem at all. Nevertheless, it explored the effect of a particular form of home-based involvement on early language and literacy skills. A particular method (i.e., dialogical reading) was introduced to the early years’ teachers, who again communicated it to the parents and gave them an assignment, which consisted of reading for the children at least three times per week. The measurements taken in the intervention and control groups revealed that dialogical reading significantly affected the four components of language and literacy skills, regardless of the family’s characteristics. Even though the researchers concluded by proving Bronfenbrenner’s hypothesis on the benefits of parental involvement, it is also important to mention that inducting such a one-sided knowledge transfer (from academics to teachers, or from teachers to parents) and introducing particular activities at the children’s homes is also a way of overlooking diverse homes’ cultures and assuming that they are not stimulating enough. The very narrow focus of this study, both in terms of the child’s development in language and literacy and parental involvement narrowed to a particular home-based activity, allows to identify a new causality (that Bronfenbrenner encouraged us to find), but it also ignores the different values of early childhood education, as well as different understandings of early childhood and the character of the relationships between parents and ECEC settings.

The relatively narrow focus of this study contrasts other kinds of studies, which assumed the mesosystem’s effect on the child (based on ecological systems theory) and focused on gaining deeper insight into what is happening in the mesosystem and how the different actors involved perceive it. An and Hodge (2013) used phenomenological inquiry to explore parental involvement in physical education for children with developmental disabilities and drew a complex picture of themes important for the parents when advocating for their own child in communication at school, becoming a team with other parents of children with disabilities, and collaborating with diverse organisations for children/families with disabilities. Studies like this one do not discover or prove new, more nuanced casualties between or among the systems, but allow us to understand the complexity and richness of this level in different local contexts, with the intent of having an impact on policies facilitating learning opportunities for all children.

A focus on children’s early learning opportunities is also presented in a study of rural contexts and the characteristics of the nested systems within them (Iruka et al., 2020). By using Bronfenbrenner’s model as a matrix, the researchers studied 10 rural school districts and re-constructed the diverse resources (and lacks), as well as networks and collaborations (that should be enabled, maintained, or strengthened), to provide the children with the best developmental opportunities.

A very interesting way of understanding the home-pre-school collaboration is provided in the article by Yngvesson and Garvis (2021), where the child is not only included in terms of developmental indicators, but as a perspective that is equally important as the ones collaborating at the mesosystem level. As this paper is one of the three related to early childhood education, it will be described in more detail in the next section.

Ecological Systems Theory in the Field of Early Childhood Education

The three articles using ecological systems theory in their research on parental involvement in ECE represented different aims and research designs. The first one (Liu et al., 2020) applied Bronfenbrenner’s theory as a matrix for a literature review, thus justifying the search for studies on parental involvement/engagement in educational settings for infants and allowing generalisations to be made with the use of other theoretical models. The second report (Kim & Riley, 2021) on an experimental study picked a very specific aspect of child development (early language and literacy) and tested how a particular form of home-based involvement on the part of the parents (dialogical reading) influences this aspect of development. The third one (Yngvesson & Garvis, 2021) assumed the child to be an important actor in the collaboration taking place at the mesosystem level and aimed to explore the three primary perspectives involved in the home-(pre)school collaboration (i.e., child, teachers, and parents), but also articulated the ambition of making the child’s voice “visible in the world of adult noise” (p. 1735). By drawing the story constellations and showing the harmonies and disharmonies between the three involved perspectives, the authors show what home-(pre)school collaboration means for the child, but also give the child – the centre of the theoretical model – a voice. A voice and not a variable identifying a particular developmental change.

The” developing person” is thus not included in terms of particular developmental indicators, but in terms of their own opinions, views, and stories on the home-(pre)school collaboration. The child’s stories, being seen in constellations with the parents’ and teachers’ stories, unmask a huge, rich landscape of adult stories that disharmonise with the child’s perspective, which can inform both the practices and policies of the mesosystem. Yngvesson and Garvis’s (2021) application of Bronfenbrenner’s theory reflectively extends the relationships at the mesosystem by showing that collaborating “about” the child does not need to exclude the child as an important actor.

Conclusion

As shown above, ecological system theory is applied in very different kinds of studies and in a variety of different ways. On the one hand, the theory allows researchers to assume a set of influences (like the home-(pre)school relationships influencing the child), which allows for deeper insight to be obtained into the diverse actors’ perspectives (An & Hodge, 2013; Iruka et al., 2020; McBrien, 2011; Yngvesson & Garvis, 2021), or to test and verify new causalities and influences within the theory-defined systems (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017; Kim & Riley, 2021).

Building on a general framework that defines influences and linkages, such studies adapt Bronfenbrenner’s ideas to various local contexts. The adaptation can expand the model (i.e., when considering several macro- and exosystems, as in the study on minority parents by McBrien, 2011), but it can also narrow it (i.e., when operationalising the child’s development and parental involvement into very specific skills and activities).

In other words, this theoretical model opens a pathway for other discourses (e.g., cultural, political, or historical) to decide which actors and the collaborations between them will be valued as worthy of inquiry. This means that the theory creates space for research on both the efficiency of established forms of parental involvement and the search for new linkages. While Yngvesson and Garvis (2021) point out the importance of the child as a figure extending the ECEC-parent collaboration into the more-than-parental, Oropilla et al. (2022; Oropilla & Ødegaard, 2021) argues for collaborations with institutions that would establish intergenerational relationships between small children and elderly adults. The model itself does not assign any additional value to any of the potential actors involved in the good life of the child; however, it also does not limit any new linkages that could be created.

Regardless of the fact that collaborations in mesosystems are undefined and open, it is clear that actors from the microsystems shall be involved in them. The family – as it is with its siblings, grandparents, the whole kindship, or just a single parent – shall be fully acknowledged as a first teacher and participant in creating environments that facilitate children’s well-being and well-becoming. This implies that ecological system theory supports the involvement of more-than-parents, depending on the shape of the microcosmos.

By including time (chronosystem) in the model, Bronfenbrenner (1979) made the model changeable over time. In my view, these changes could embrace tensions to a greater degree rather than interpret them as layers of influence. In a world of increasing complexity, diversity, and speed, embracing spaces that allow for contradicting forces, agonism, and the sharing of diverse voices seems to be of great importance.

Overview over Articles Included in Scoping Literature Review

An, J., & Hodge, S. R. (2013). Exploring the meaning of parental involvement in physical education for students with developmental disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 30(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.30.2.147

Day, E., & Dotterer, A. M. (2018). Parental involvement and adolescent academic outcomes: Exploring differences in beneficial strategies across racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(6), 1332–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0853-2

Diab, S., Palosaari, E., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2018). Society, individual, family, and school factors contributing to child mental health in war: The ecological-theory perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect, 84, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.033

Espelage, D. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947216

Hampden-Thompson, G., & Galindo, C. (2017). School-family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people. Educational Review (Birmingham), 69(2), 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1207613

Holt, N. L., Tamminen, K. A., Black, D. E., Sehn, Z. L., & Wall, M. P. (2008). Parental involvement in competitive youth sport settings. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(5), 663–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.08.001

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Hong, J. S., Hunter, S. C., Kim, J., Piquero, A. R., & Narvey, C. (2021). Racial differences in the applicability of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model for adolescent bullying involvement. Deviant Behavior, 42(3), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1680086

Ilari, B., Perez, P., Wood, A., & Habibi, A. (2019). The role of community-based music and sports programmes in parental views of children’s social skills and personality. International Journal of Community Music, 12(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.12.1.35_1

Iruka, I. U., DeKraai, M., Walther, J., Sheridan, S. M., & Abdel-Monem, T. (2020). Examining how rural ecological contexts influence children’s early learning opportunities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 52, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.09.005

Keyes, C. (2002). A way of thinking about parent/teacher partnerships for teachers Le partenariat parent/enseignant: Un autre point de vue Una forma de reflexionar sobre la asociacio’n Padre/Maestro para maestros. International Journal of Early Years Education, 10(3), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976022000044726

Kim, Y., & Riley, D. (2021). Accelerating early language and literacy skills through a preschool-home partnership using dialogic reading: A randomized trial. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(5), 901–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09598-1

Koller, S., Raffaelli, M., & Morais, N. A. (2020). From theory to methodology: Using ecological engagement to study development in context. Child Development Perspectives, 14(3), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12378

Kulik, L., & Sadeh, I. (2015). Explaining fathers’ involvement in childcare: An ecological approach. Community, Work & Family, 18(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2014.944483

Liu, Y., Sulaimani, M., & Henning, J. E. (2020). The significance of parental involvement in the development in infancy. Journal of Educational Research & Practice, 10(1), 161–166.

McBrien, L. (2011). The importance of context: Vietnamese, Somali, and Iranian refugee mothers discuss their resettled lives and involvement in their children’s schools. Compare, 41(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2010.523168

Sheoran, S., Chhikara, S., & Sangwan, S. (2019a). Analyzing musical intelligence of young adolescent girls’ with regard to their human ecological variables. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 10(4–6), 126–128.

Sheoran, S., Chhikara, S., & Sangwan, S. (2019b). An experimental study on factors influencing the musical intelligence of young adolescents. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(2), 96–99.

Yngvesson, T., & Garvis, S. (2021). Preschool and home partnerships in Sweden, what do the children say? Early Child Development and Care, 191(11), 1729–1743. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1673385

Ziaei, S., & Hammarström, A. (2021). What social determinants outside paid work are related to development of mental health during life? An integrative review of results from the Northern Swedish Cohort. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–2190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12,143-3

References

Bennett, J. (2010). Pedagogy in early childhood services with special reference to Nordic approaches. Psychological Science and Education, 3, 16–21.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1975). Reality and research in the ecology of human development. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 119(6), 439–469.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1991). What do families do? Institute for American Values, Winter/Spring, p. 2.

Ejuu, G., & Opiyo, R. A. (2022). Nurturing Ubuntu, the African form of human flourishing through inclusive home based early childhood education. Frontiers in Education (Lausanne), 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.838770

Eliyahu-Levi, D. (2022). Kindergarten teachers promote the participation experience of African Asylum-Seeker families. International Migration. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13037.

Fenech, M., & Skattebol, J. (2021). Supporting the inclusion of low-income families in early childhood education: An exploration of approaches through a social justice lens. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(9), 1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1597929

Gedal Douglass, A., Roche, K. M., Lavin, K., Ghazarian, S. R., & Perry, D. F. (2021). Longitudinal parenting pathways linking Early Head Start and kindergarten readiness. Early Child Development and Care, 191(16), 2570–2589. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1725498

Halpenny, A. M., O’Toole, L., & Hayes, N. (2017). Introducing Bronfenbrenner. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646206

McKee, L., Murray-Orr, A., & Throop Robinson, E. (2022). Preservice teachers engage parents in at-home learning: “We are in this together!”. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v16i1.6849

Oropilla, C. T., & Ødegaard, E. E. (2021). Strengthening the call for intentional intergenerational programmes towards sustainable futures for children and families. Sustainability, 13(10), Article 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105564

Oropilla, C. T., Ødegaard, E. E., & Quinones, G. (2022). Kindergarten practitioners’ perspectives on intergenerational programs in Norwegian kindergartens during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring transitions and transformations in institutional practices. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2022.2073380

Sengonul, T. (2022). A review of the relationship between parental involvement and children’s academic achievement and the role of family socioeconomic status in this relationship. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 12(2), 32–57.

Uysal Bayrak, H., Gözüm, A. I. C., & Özen Altinkaynak, S. (2021). Investigation of the role of preschooler parents as teachers. Bulletin of Education and Research, 43(1), 155–179.

Warren, J. M., & Locklear, L. A. (2021). The role of parental involvement, including parenting beliefs and styles, in the academic success of American Indian students. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 2156759X2098583. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20985837

Wright, T., Ochrach, C., Blaydes, M., & Fetter, A. (2021). Pursuing the promise of preschool: An exploratory investigation of the perceptions of parents experiencing homelessness. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(6), 1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01109-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sadownik, A.R. (2023). Bronfenbrenner: Ecology of Human Development in Ecology of Collaboration. In: Sadownik, A.R., Višnjić Jevtić, A. (eds) (Re)theorising More-than-parental Involvement in Early Childhood Education and Care. International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development, vol 40. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38762-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38762-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-38761-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-38762-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)