Abstract

Although there is some research on how very young children engage in mathematical activities, little is known about how teachers facilitate this engagement through digital tools. In this paper, the relationship between digital apps, kindergarten teachers’ facilitation and 18-month-old children’s mathematical engagement is explored. Artefact-centric activity theory was used to analyse video recordings of children and a kindergarten teacher engaging with three digital apps. The results show how children engaged with the mathematical activity of locating and that the teacher facilitated their engagement by following the children’s interests and adding verbal and body language to what the children did on the tablet they were using. The apps’ design supported the opportunities that the teachers had to facilitate children’s engagement with aspects of locating, to different degrees. The results provide information about the kinds of apps that could support the youngest children’s mathematical engagement, and how kindergarten teachers can facilitate young children’s digital explorations of locating.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Digital tools are becoming increasingly more common all over the globe, with young children encountering them at home as well as in early childhood education (Otterborn et al., 2019). Although there is some research on older children using digital tools, little is known about the youngest children, especially when it comes to mathematics. Yet digital tools receive a lot of political attention, with an OECD report stating that “linking the way children interact with ICT inside of school to the way they already use it outside of school can be a key to unlocking technology’s potential for learning” (Schleicher, 2019, p. 10). Similarly, a link between play and learning is commonly made in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) practice and research (Nilsson et al., 2018). For example, Lundtofte’s (2020) literature review of children’s tablet play found that children’s use of tablets is often connected to digital literacy and learning.

In this article, I investigate how two one-and-a-half-year-old children and a kindergarten teacherFootnote 1 engaged with playful digital apps together in a Norwegian kindergarten. Across the Scandinavian countries, digital practices are part of the national curricula for ECEC (Børne-og Socialministeriet, 2018; Ministry of Education, 2017; Skoleverket, 2018) and, consequently, teachers are expected to facilitate their use. In Norway, although kindergarten is voluntary for children aged 1–5 years old, in 2021, 87% of children between 1 and 2 years old attended kindergarten (SSB, 2022). Given that toddlers encounter digital practices in kindergarten and elsewhere, more research is needed to explore how this age group engages in digital activities, particularly those which facilitate very young children’s mathematical engagement. This article aims to construct knowledge about how the design of digital apps supports kindergarten teachers in doing this. Therefore, the research question is: in what ways can digital apps mediate the way kindergarten teachers support the youngest children’s engagement in the mathematical activity of locating?

Teaching in Digital Environments

Although digital tools such as mobile technologies have been around for some time, their entry into early childhood education remains contested, with opinions often divided into two groups: those who see digital tools as a threat, and those who think they can make the world better (Danby et al., 2018; Palaiologou, 2016). Given this contested space, it can be challenging for teachers to implement digital tools in their teaching. Vangsnes et al. (2012) suggested that teachers rarely bring the Nordic pedagogy of valuing play into digital game-playing, indicating that the digital tools’ entry into kindergarten might entail a risk of changing the children’s pedagogical environment to one with less focus on children’s play (Christiansen & Meaney, 2020). Fleer (2014) argued that that there is a need for further research to recognize new opportunities for play in digital settings.

Tablets with multitouch capabilities are often considered an intuitive tool suitable for children’s developing coordination skills. For example, Geist (2012) found that when toddlers use digital touch screens, they showed a high level of skills in using the screens independently, and explored options in similar ways to how they used other play materials such as building blocks. Nevertheless, digital apps for children are often given a strong learning focus, being marketed as “fun learning” (Kvåle, 2021). In apps with a linear build-up of tasks, children can often guess their way to the correct answer and seem to be motivated by the digital stardust or confetti they get for finding the right answer, rather than by learning ideas or concepts (Nilsen, 2018). Children can also change the purpose of digital activities from what was planned by teachers. Lafton (2019) found that children playing a digital memory game ignored the intended rules of the game, and instead created their own game with different rules. Digital apps with strong framing, those with clear control over the communication and the pace of the app, can sometimes limit children’s participation (Palmér, 2015). Lembrér and Meaney (2016) suggested that children’s agency could be strengthened by giving them control over the game, which could lead to them needing or wanting to explain what they were doing. This need could support children’s reflective mathematical thinking. Playful apps with a weak framing, where the app provides the children with control, could engage children in mathematical language and thinking when they played by themselves (Christiansen, 2022).

Theoretical Framework

This article is part of a wider study where I have used Bishop’s (1988) six fundamental mathematical activities to describe children’s mathematics. In this article, I focus on the mathematical activity of locating as this is mostly what these very young children engaged with when using digital apps. To investigate how digital apps mediate kindergarten teachers’ support, I use Ladel and Kortenkamp’s (2011, 2014) artefact-centric activity theory (ACAT) which has been developed to capture the complexity of children’s use of digital tools.

The Mathematical Activity of Locating

More than 30 years ago Bishop (1988) identified locating as one of six mathematical activities that are present in all cultures. In Norway, the curriculum known as the Framework Plan for Kindergartens (Ministry of Education, 2017) includes the learning area of quantities, spaces and shapes, which is based on Bishop’s (1988) activities (Reikerås, 2008). Researchers have also found that situations involving Bishop’s (1988) activities are present in children’s culture (for example, Helenius et al., 2016; Johansson et al., 2014).

Bishop (1988) described locating as more or less sophisticated activities connected to navigating and communicating about the environment which are closely linked to language as language develops through taking part in these situations. Lowrie (2015) found that video games for 5-year-old children required visuospatial skills similar to those needed in real life-situations, suggesting that digital games can provide opportunities to engage children in locating activities. Although verbal language can both make locating ideas easier to spot and focus the children’s attention on the mathematical aspects of a situation, children are also able to engage in the different mathematical activities without using verbal language (Flottorp, 2010; Meaney, 2016). Children’s engagement with locating ideas does not have to be done through verbal language. What remains unknown is how apps might mediate the kind of support, including the development of verbal mathematical language, that teachers could provide to increase young children’s opportunities to engage in locating tasks.

Artefact-Centric Activity Theory

Children’s engagement with multitouch screens such as tablets is complex. To deal with this complexity, Ladel and Kortenkamp (2011, 2014) developed artefact-centric activity theory (ACAT), based on Engeström’s (2015) activity theory. ACAT theorises the relationship between the child, the app, the mathematics and others who participate in the activity. ACAT describes how the app mediates the processes the children engage in, rather than assessing their learning outcomes (Ladel & Kortenkamp, 2014). In this theory, the artefact (in this case the digital app) is at the centre and is affected by and affects four components: subject, group, rules and object. The model describes how the interaction between the subject (child) and the object (mathematics) is mediated through the artefact (the digital app). By using ACAT, it is possible to show how the app’s design affects children’s mathematical involvement and to discuss how digital apps mediate the way kindergarten teachers support the youngest children’s mathematical engagement (Fig. 1).

ACAT from Ladel and Kortenkamp (2011, p. 66)

The ACAT model consists of two triangles. In the first triangle, the artefact (the digital app) is connected to the nodes for rules (how the app is designed) and the object (the mathematical content). The triangle describes how the mathematical object is internalized in the app and then externalized through the tablet’s design. The rules (the design principles of the app) describe how the mathematical object is presented in the app (what kind of activities and feedback are available).

In the second triangle, the focus is on how the artefact (the digital app) is used by the subject (the child who is playing) and the relationship to the group (the social group around the child). The focus is on what the subject internalizes from engaging with the app, and how the subject externalizes that engagement through their words and actions. The group influences the child’s engagement because it can facilitate or hinder, or be facilitated or hindered, by the way that the app presents the mathematical content (as a basis for what happens in the first triangle).

Methodology

As part of a wider project, video recordings were made of children engaging with digital tools at a Norwegian kindergarten over a 2-month period. For this article, I analyse 20 min of video, where two one-and-a-half-year-old children, Ole and Trine, played with three digital apps with a teacher.

Informants and the App

The teacher was informed about the wider project in a series of staff meetings before filming began. She gave her informed consent to be part of the project. The parents also gave written consent for their children’s participation after a parents’ evening was held to inform about the project. The children were given time to get to know the researcher before the video recordings began. The video recordings were carried out in the rooms the children usually used in the kindergarten, and they were always with one of their permanent teachers. There was an agreement to turn off the camera if the children seemed uncomfortable with being filmed. The two children were learning Norwegian as their first language. In the videos, the children engage with three different apps which they chose from what the kindergarten staff made available on the tablets. These apps were: My PlayHome, an app designed to excite and captivate children (My PlayHome, 2022); Toca Kitchen, an app designed for play (TOCA BOCA, 2022); and Crocro’s Friends Village, an app designed to “both entertain and encourage them [children] to learn, develop, and flourish” (Samsung, 2022). Both the children had previously tried all three apps.

Analysis

Transforming the video data into written text was the first step in the analysis. I started by transcribing verbal utterances and adding in screenshots of the actions connected to what was happening on the screen, inspired by Cowan (2014) (see Table 1). To identify how the app mediated the kindergarten teacher’s support of the children’s locating, I examined the transcripts from the videos carefully many times, and returned to the video if I was uncertain about something.

I then organized the analyses into two parts, each part focused on one of the triangles in ACAT. Everything related to how the children used the app to engage with the mathematical activity of locating (actions and vocabulary linked to locating and navigating in the virtual space of the app) was coded as part of the rules–object–artefact triangle.

Following earlier research on children engaging with apps (Christiansen & Meaney, 2020; Geist, 2012; Kvåle, 2021; Nilsen, 2018). I wanted to examine apps which did not have (mathematics) learning as a stated aim of the app. Therefore, the chosen video recordings did not include the children using apps that were described by their developers as educational.

After watching the children’s engagement, I identified locating as a mathematical object that was made available to the children through playing with the app. It may be that the teacher did not think that she was focusing on mathematics or locating when engaging with the apps with the children. However, this way of engaging in mathematics through playful participation is in line with the Norwegian framework plan which states that children should learn through play (Ministry of Education, 2017). In the video, the teacher appeared to focus on communicating about the children’s navigating, and communicating about the environment, which is in line with Bishop’s (1988) understanding of locating.

Everything related to how the child and the group around the child interacted with the app was coded as part of the subject–group–artefact triangle. In ACAT, the role of the teacher is not explicit, but the teacher is part of the “group” in the subject-group-artefact triangle. In the recordings, the children each had a tablet, but they mostly focussed on Ole’s screen. Therefore, I have made Ole the subject of the analysis. Trine and the teacher are part of the social group around Ole. The choices for this coding are discussed in more detail in the findings and discussion section.

Findings and Discussion

To answer the research question, I describe how the three digital apps supported the kindergarten teacher in facilitating the youngest children’s locating. I found that the pace of the apps appeared to have an impact on what kind of conversation the teacher and the children engaged in. If an app operated at a slow pace, there was an increase in opportunities for the teacher to facilitate children’s engagement with aspects of locating. Lembrér and Meaney (2016) had noted a similar result with preschool children using an interactive table and a balancing app.

Crocro’s Friends Village

The first triangle of ACAT focus on rules-object-artefact. In the video, I identified aspects of locating externalised through the app as a result of its design, especially the feedback provided to the child when they interacted with the app. Ole touched the screen on the sloth’s floor (see Fig. 2, left). The app provided feedback in that it zoomed into this floor of the building. Ole was then in the sloth’s virtual home. It was unclear if this was a deliberate move by Ole. The reaction of the app provided Ole with the opportunity to see how his actions allowed him to move between the outside and the inside of the building. This indicates two kinds of locating; a virtual one where Ole moved inside a building from being outside, and a physical one in which moving his finger around the screen changed what appeared on the screens. At this point, neither the teacher nor Trine made any comments verbally or with gestures about either aspect of locating.

On the next screen, there was a fishbowl in front of the sloth and fish were flying from left to right, over the sloth’s head, along with some boots (see Fig. 2, centre). Ole dragged his finger across the screen several times where the fish were flying, but the app did not respond. Ole seemed aware of the movement of the objects, suggesting that he had an opportunity to engage with aspects of locating such as moving from left to right. He also seemed to expect that touching the moving fish would result in something happening. The object flying over the app appeared to fly at a pace which required visuospatial skills beyond what Ole had at this time.

After a few seconds, Ole stopped touching the screen. The teacher asked, “What will happen if we press the apple?” and pointed to the apple at the bottom of the screen. In this way, the teacher supported Ole in locating other items which may have been difficult to see because of the many small items on the screen. Ole pressed the apple and the fishbowl was replaced with a salad bowl (Fig. 2, right), where different fruit and footballs appeared and disappeared. Ole tapped the fruit but again the app did not respond. Then the teacher suggested, “Maybe he wants to have it inside his stomach”? Ole dragged the fruit towards the sloth’s mouth: the sloth ate it, smiled and gave the ‘ok sign’. The design of the app provided feedback to Ole which supported him to see that feeding fruit to the sloth would make it respond, unlike tapping on the fruit. He then engaged with locating aspects of moving items around the virtual space. The actions of the sloth seemed to motivate Ole to continue exploring by pulling something else from the salad bowl. The screen changed back to the fishbowl. Ole went back to tapping the screen, which did not result in the sloth responding.

The second triangle focused on how the app (the artefact) was used by Ole (the subject) and his interactions with Trine and the teacher when playing with the app (the group). When the teacher suggested that “maybe he wants to have it inside his stomach” Ole was guided towards trying something new, and the teacher was able to focus on locating by asking, “Should he (the sloth) put it in his mouth?” Trine then put her finger inside her mouth and the teacher held her hand in front of her mouth. Trine did the same and the teacher said “Now we will be full up. In our stomachs” and rubbed her stomach. This exchange would have helped the children to understand about different parts of their own bodies, such as their mouth where food goes in, and their stomach where food ends up. Locating different parts of their bodies and knowing their names, such as stomach, are new and relevant aspects for many young children to learn.

In Crocro’s Friends Village, there was a lot of quickly-moving objects. Ole did not have the fine motor skills needed to navigate the app, and consequently he did not always get feedback from the app that supported his engagement with aspects of locating, apart from watching the items move from left to right and tapping on the fish on the screen. The teacher’s communication, even if it was not explicitly about aspects of locating, appeared to support Ole to keep exploring. However, it seemed as if the somewhat fast-moving items, and a large number of small items on the screen, made it challenging for the teacher to engage in a discussion about this with Ole.

Toca Kitchen

In Toca Kitchen there were also internalized possibilities to engage with locating. These possibilities were externalized through a virtual environment in which the children had a range of options. The feedback was different depending upon the choices made. When opening the app, the children could choose a boy, a girl or a monster (Fig. 3, left). Trine pressed the monster, but as had been the case with Ole’s choice of the sloth’s apartment when playing Crocro’s Friends Village, it is unclear whether Trine’s choice was deliberate. Nonetheless, once the monster was chosen, the app then showed a virtual kitchen. Pressing the monster showed the children how moving their fingers and tapping on the screen would lead to changes on the screen. Both aspects of locating to do with locating themselves in the virtual environment produced changes in the app.

Trine tapped the screen and a door opened showing a range of cooking implements, such as a saucepan and a blender (see Fig. 3, centre). Again, it seemed that Trine did this randomly. She then touched the middle of the screen and the door to the kitchen equipment closed. Ole stretched his finger towards the monster, slightly touching the fridge door which opened (Fig. 3, centre). The teacher said “He was hungry. He’s got a melon, a mushroom and some bread.” She pointed to each item. “What do you want to eat, Trine”? Trine said something inaudible and pressed the onion. After one wrong try, Trine pressed the onion which made it fall from the fridge onto the table. Similarly, Ole struggled to feed the monster, suggesting that the app was difficult to navigate. The aspects of locating were to do with dragging the food from the fridge to the monster’s mouth. At times, the feedback from the app did lead to the monster eating the food, but when unsuccessful led to the fridge door closing. Ole and Trine externalized locating through words and actions only to a small extent.

However, the teacher focused Ole and Trine’s attention on locating by adding words to the onion going into the monster’s mouth. Using language to discuss environments is, according to Bishop (1988), part of locating. The teachers’ support is also connected to supporting Ole and Trine in exploring the options available within the app. When the onion fell out of the fridge, the teacher opened the cooking menu and suggested that the children use it by asking “what do we have to do now”? However, when neither of the children responded to her invitation to explore the cooking options, she closed the menu.

In Toca Kitchen, opportunities for engaging in locating were externalized through the opportunities to move the objects, and because moving the object towards the monster’s mouth would result in the monster eating the food. Although this app moved at a slower pace than Crocro’s Friends Village, it appeared to be difficult for the children to navigate; for instance when one wrong tap would close the fridge. The children were interested in, and managed to give the monster food to eat, and the teacher and the children discussed how the food disappeared and went into the stomach, also by using gestures such as rubbing their stomach.

My PlayHome

In My PlayHome, locating is externalized through movable objects in the room and through the opportunity to navigate between the rooms by touching the arrows or dragging items toward the arrow (see Fig. 3). Ole tapped a dog, making it move around. The teacher said, “There it was a dog”, and Ole continued to tap the dog and make it move. Suddenly he also started moving a mirror hanging on the wall. The teacher then stretches in and said “You are moving the mirror. Here, can you move it”? The teacher thus focused the children’s attention on the movable parts in the app. Ole continued to tap the dog and say “tap woof-woof”. The teacher said: “Oh, you have to tap woof-woof, then he will move. Can you see him walking along”? The teacher traced her finger in the direction the dog had moved, focussing on how Ole changed the dog’s positioning in the app. Ole then repeated the teacher’s movement and instead of tapping the dog he dragged it along the screen making it move further than before. He did it again, and this time he moved it onto the wall. The teacher said “Oh, now he jumped”, and again she pointed to where the dog jumped from and where he jumped to. Ole said: “Oh, no. Go down” and tried to move the dog down from the wall by dragging his finger across the dog. Although Ole moved the dog further than planned, he experienced that he could drag items around in the room. The teacher focussed Ole’s attention on locating, by using words and gestures that describe how the dog moved in the virtual room.

Ole closed the app and opened it again, this time in a room with a chair and a grandfather. Ole said “Grandad sit there” and pointed to a chair. The teacher replied, guiding Ole to explore how he could get the granddad to sit: “Should he sit there? Then we have to move him. Can you tap on him”? Ole started tapping him, but switched to dragging. He dragged him up the ceiling at the top of the screen making him move one floor up into a bathroom (from bottom left to top left in Fig. 3). The teacher said “Oh, now he is in the bathroom” and Ole said “Into the shower” and tried to drag him into the shower but ended up dragging him into the bedroom next door (from top left to top right in Fig. 3).

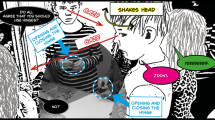

Ole ended up in a different virtual room with a bed. Ole dragged a baby onto the bed and pulled the blanket up (see Fig. 4). The teacher said “Oh, you pulled the blanket” and Ole replied “Oh no, baby!” sounding distressed. The teacher said “He’s gone. He’s gone. Where is he”? Ole said “There” while pointing at the bed. He pulled the blanket back, making the baby visible again, and this made Trine say something inaudible while sounding excited. Ole moved the baby off the bed, put it back, and continued to pull the blanket back and forth. Trine and the teacher were commenting on the baby appearing and disappearing.

When using My PlayHome, the children appeared to be interested in making things move, and both Ole and the teacher externalized language related to locating. The teacher’s language focused the children’s attention on locating, through using verbal language such as the baby being in the bed; the dog moving, jumping, walking along; the baby was gone and there. My PlayHome has the option of undoing actions. Unlike Crocro’s Friends Village and Toca Kitchen, where Ole and Trine only had the option of doing the same thing over again, in My PlayHome they could move items back and forth. Ole explored this option when he covered and uncovered the baby with the blanket, encouraged by his own reaction when the baby ‘disappeared’, the teacher’s question “Where is he?” and Trine’s excitement when the baby was still in the bed. Even if Ole navigated between rooms without doing so intentionally, this is a relatively slow-moving app where the children actively have to make something move by dragging it, although they sometimes make them move further than planned. The slow pace gave the children the opportunity to explore the virtual space at a slower pace than in the two previous apps, and this also provided space for the teacher to mediate the locating through active engagement around the app. The teacher not only voices what the children are doing, but also uses gestures to underline the locating, such as showing the children that they are moving the mirror and tracing the dog’s movement on the screen. The tracing of the dog’s movement appears to encourage Ole to try to drag items instead of just tapping them.

Conclusion

The findings show that the apps provide opportunities for engaging in locating. This is because they provide opportunities for users, such as Ole and Trine using their fingers to make things move in the app, and such as opening cupboard doors in Toca Kitchen. When Ole and Trine interact with the apps, they do so mostly through body movements, and sometimes using verbal language to express what they are doing or want to do. The locating in the virtual word can sometimes lead to discussing locating in the actual world, for instance when Trine put her finger in her mouth, showing where the food went. With the very young children, it seems that the teacher has a key role in mediating locating.

Although Ole did explored the apps to some degree, as Geist (2012) found toddlers can do, moving small objects in the virtual space required good fine motor skills and this has an impact on the aspects of locating that the children could engage with. In Crocro’s Friends Village, the need for fine motor skills was combined with fast-moving objects. In Toca Kitchen, many things were happening on the screen at the same time. These design features of the apps appeared to make it harder for the children to engage with the opportunities for exploring aspects of locating by playing with the app. When the children use My PlayHome, the pace is much slower. Although there is no built-in need for explanation such as Lembrér and Meaney (2016) suggest there should be when (older) children take part in the game, My PlayHome provides opportunities to discuss what is happening, especially when Ole pulls the blanket over the baby, and he can pull it back and forth many times to both see and discuss what is happening.

Although playful apps have been shown to engage older children in mathematical language and thinking when they play by themselves (Christiansen, 2022), these younger children did not use a lot of verbal language when they engaged with any of the three apps. As the digital apps did not provide any verbal input, the teacher was the only one providing models of mathematical language. It was the teacher who voiced what the children did in relationship to aspects of locating in the virtual environments. In fast-moving apps, it was harder for the teacher to focus the children’s attention on these opportunities, as something new is happening all the time. The teacher had a key role as the mediator of the mathematics; the mathematical object (locating) is externalized to the children through what is seen on the screen and how they use their fingers to interact with it, but also through the teacher’s verbalization. The differences in how the three apps provided opportunities for children’s interactions on the screen.

The teacher focused on the aspects of locating that the children were interested in and allowed the children to decide what to do and how to do it. For example, with My PlayHome, the teacher followed what the children did, rather than limiting their exploration so that they were guided towards solving tasks. The teacher appeared to value the play, both in that she did not insist that the children engage with apps with what Kvåle (2021) call ‘fun learning’, and because she let the children explore freely while she highlighted aspects of locating. The kindergarten teacher seizes the space for action that arises when the child faces digital challenges and use it as an opportunity to discuss the mathematical object of locating.

The teacher has an important role when young children engage with apps designed for play as the teacher becomes a mediator of the mathematical content in the app, just like the app itself. The teacher both highlights the mathematics in the app (in this case locating) and underlines the way the app externalizes the feedback, such as when she says to Ole that the dog is moving when he taps it. As the teacher has this key role as a mediator of the mathematical object, I suggest that the model of ACAT should be expanded by adding a third triangle where the connection between the group (in this case Trine and the teacher) is highlighted.

Figure 5 illustrates how ACAT can be expanded to include the teacher’s mediating role. The red arrows illustrate the relationship between the teacher and the mathematical content; the object designed in the app enables the teacher to focus on the mathematics, and the teacher focuses the children’s attention on the mathematical opportunities designed in the app.

Elaboration of the ACAT from Ladel and Kortenkamp (2011, p. 66)

In this study, I have shown that although digital apps have the potential to engage even very young children in locating and the teacher might have a key role as a mediator of the mathematical object. The design of apps which provide an open virtual environment for children to explore at their own pace can provide spaces where the teacher can focus the children’s attention on locating by adding words to what the children are engaged in. Of the apps that have been investigated in this study, the non-linear and slow-moving apps without verbal language appeared to provide the best opportunities for such spaces for verbal language contributions from the teacher, who provided a supportive environment for the children’s own explorations. Although ACAT was useful in helping me make sense of the data, it was clear that the teacher’s role was not sufficiently highlighted in supporting the children in engaging with the mathematical objects of learning. Theoretical models used to analyse children’s digital engagements need to recognize the importance of the teacher. For future research, I would suggest looking into how digital apps can support other mathematical activities and whether the design elements in other apps can support engagement with all of Bishop’s (1988) mathematical activities.

Notes

- 1.

Kindergarten teachers in Norway have a bachelor’s degree in kindergarten teacher education, and make up 42.3% of the staff in kindergarten (UDIR, 2022).

References

Bishop, A. J. (1988). Mathematical enculturation: A cultural perspective on mathematics education. Kluwer.

Børne-og Socialministeriet. (2018). Den styrkede pædagogiske læreplan: Rammer og indhold. Retrieved from: https://emu.dk/sites/default/files/2021-03/8077%20SPL%20Hovedpublikation_UK_WEB%20FINAL-a.pdf

Christiansen, S. F. (2022). Multilingual children’s mathematical engagement with apps: What can be learned from multilingual children’s mathematical and playful participation when interacting with two different apps? Conjunctions - Transdisciplinary Journal of Cultural Participation, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.2478/tjcp-2022-0009

Christiansen, S., & Meaney, T. (2020). Cultural meetings? Curricula, digital apps and mathematics education. Journal of Mathematics and Culture, 14(2), 71–90.

Cowan, K. (2014). Multimodal transcription of video: Examining interaction in early years classrooms. Classroom Discourse, 5(1), 6–21.

Danby, S. J., Fleer, M., Davidson, C., & Hatzigianni, M. (2018). Digital childhoods across contexts and countries. In S. J. Danby, M. Fleer, C. Davidson, & M. Hatzigianni (Eds.), Digital childhoods. Technologies and children’s everyday lives (pp. 1–14). Springer.

Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by expanding - An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Cambridge University Press.

Fleer, M. (2014). The demands and motives afforded through digital play in early childhood activity settings. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 3(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.02.012

Flottorp, V. (2010). Hvordan kommer matematisk meningsskaping til syne i barns lek? En casestudie. Tidsskrift for Nordisk barnehageforskning, 3(3), 95–104. https://journals.hioa.no/index.php/nbf/article/view/278/292

Udir. (2017). Framework Plan for Kindergartens – contents and tasks. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf

Geist, E. A. (2012). A qualitative examination of two-year-olds interaction with tablet based interactive technology. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 39(1), 26–35.

Helenius, O., Johansson, M. L., Lange, T., Meaney, T., Riesbeck, E., & Wernberg, A. (2016). When is young children’s play mathematical? In T. Meaney, T. Lange, A. Wernberg, O. Helenius, & M. L. Johansson (Eds.), Mathematics education in the early years: Results from the POEM2 conference 2014 (pp. 139–156). Springer.

Johansson, M., Lange, T., Meaney, T., Riesbeck, E., & Wernberg, A. (2014). Young children’s multimodal mathematical explanations. ZDM, 46(6), 895–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-014-0614-y

Kvåle, G. (2021). Stars, scores, and cheers: A social semiotic critique of “Fun” learning in commercial educational software for children. In M. G. Sindoni & I. Moschini (Eds.), Multimodal literacies across digital learning contexts (pp. 57–71). Routledge.

Ladel, S., & Kortenkamp, U. (2011). An activity-theoretic approach to multi-touch tools in early maths learning. The International Journal for Technology in Mathematics Education, 20(1), 3–8.

Ladel, S., & Kortenkamp, U. (2014). Number concepts—processes of internalization and externalization by the use of multi-touch technology. In Early mathematics learning (pp. 237–253). Springer.

Lafton, T. (2019). Becoming clowns: How do digital technologies contribute to young children’s play? Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949119864207

Lembrér, D., & Meaney, T. (2016). Preschool children learning mathematical thinking on interactive tables. In T. Meaney, O. Helenius, M. L. Johansson, T. Lange, & A. Wernberg (Eds.), Mathematics education in the early years: Results from the POEM2 conference, 2014 (pp. 235–254). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23935-4

Lowrie, T. (2015). Digital games, mathematics and visuospatial reasoning. In T. Lowrie & R. Jorgensen (Eds.), Digital games and mathematics learning: Potential, promises and pitfalls (pp. 71–92). Springer.

Lundtofte, T. E. (2020). Young children’s tablet computer play. American Journal of Play, 12(2), 216–232.

Meaney, T. (2016). Locating learning of toddlers in the individual/society and mind/body divides. Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education, 21(4), 5–28.

MyPlayHome. (2022). My PlayHome. Retrieved 19.01. from http://www.myplayhomeapp.com/

Nilsen, M. (2018). Barns och lärares aktiviteter med datorplattor och appar i förskolan [Doctoral degree, Göteborgs universitet]. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/57483/1/gupea_2077_57483_1.pdf.

Nilsson, M., Ferholt, B., & Lecusay, R. (2018). The playing-exploring child: Reconceptualizing the relationship between play and learning in early childhood education. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 19(3), 231–245.

Otterborn, A., Schönborn, K., & Hultén, M. (2019). Surveying preschool teachers’ use of digital tablets: General and technology education related findings. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 29(4), 717–737.

Palaiologou, I. (2016). Teachers’ dispositions towards the role of digital devices in play-based pedagogy in early childhood education. Early Years, 36(3), 305–321.

Palmér, H. (2015). Using tablet computers in preschool: How does the design of applications influence participation, interaction and dialogues? International Journal of Early Years Education, 23(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2015.1074553

Reikerås, E. (2008). TEMAHEFTE om antall, rom og form i barnehagen. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

Samsung. (2022). Kids’ first steps into the digital world with Samsung Kids. Retrieved 09.22 from https://www.samsung.com/hk_en/apps/samsung-kids/

Schleicher, A. (2019). Helping our youngest to learn and grow. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264313873-en

Skoleverket. (2018). Läroplan för förskolan, Lpfö 18. Stockholm. Retrieved from: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6bfaca41169863e6a65d5aa/1553968116077/pdf4001.pdf

SSB. (2022, 3. mars). Barnehager. https://www.ssb.no/barnehager

TOCA BOCA. (2022). Apps for play. https://tocaboca.com/

Udir. (2022). The Norwegian Education Window 2022. Utdanningsdirektoratet. Retrieved from: https://www.udir.no/in-english/the-education-mirror-2022/kindergarten/staff-in-kindergartens/

Vangsnes, V., Økland, N. T. G., & Krumsvik, R. (2012). Computer games in pre-school settings: Didactical challenges when commercial educational computer games are implemented in kindergartens. Computers & Education, 58(4), 1138–1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Christiansen, S. (2024). Supporting One-Year-Olds’ Digital Locating: The Mediating Role of the Apps and the Teacher. In: Palmér, H., Björklund, C., Reikerås, E., Elofsson, J. (eds) Teaching Mathematics as to be Meaningful – Foregrounding Play and Children’s Perspectives. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37663-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37663-4_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-37662-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-37663-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)