Abstract

A broad range of literature discusses the link between pretend play and learning. More specifically, the close link between pretend play and mathematics highlights the urge to develop the mathematical thinking of children through pretend play activities. In this case, collective play-related thinking (CPRT) is used as a tool to promote awareness on the mathematical aspects of a pretend play activity. The aim of this case report is to investigate the practices used by a preschool teacher to seize mathematical teaching opportunities during a CPRT. Results suggest the use of four practices by the teacher: guiding a two-level intersubjectivity, fostering the development of an imaginary situation, raising awareness on challenges, and creating meaning between symbolization in the play and symbolization in a cultural tool. The study contributes to our understanding of the dialectic between play-related thinking and mathematical thinking through a CPRT.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

From an historico-cultural perspective, pretend play holds an important place and is thought to create a zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1966/2016). In fact, when children play, they “jump above the level of [their] normal behavior” (Vygotsky, 1966/2016, p. 18) by taking advantage of the degrees of freedom to manipulate and explore their environment (van Oers, 2014). Vygotsky (1966/2016) suggests that during pretend play, children create an imaginary situation in which they substitute objects meaning, take roles, and define rules associated with these roles. Furthermore, pretend play constitutes the leading activity for children aged between 3 and 7 (Vygotsky, 1966/2016). Meaning that even if children do not engage most of their time in pretend play activities, it is thought to drive their development.

Pretend play is associated with the development of different cognitive and socio-affective competencies, some of which are associated in particular with the development of mathematical thinking (Amrar & Clerc-Georgy, 2020). During free play, more than half of the play time is devoted to the exploration of mathematical concepts (Seo & Ginsburg, 2004). During pretend play, a wide range of mathematical activities are explored (van Oers, 1996). According to van Oers (1996), when mathematical activities initiated by children are seized by the teacher, they become mathematical teaching opportunities. Together, these studies show the importance of scaffolding the pretend play components dialectically with the mathematical activities initiated by children during play.

However, many preschool teachers restrain from intervening during child-initiated activities, by fear of interrupting the children’s play. As a result, many opportunities to sustain the development of children are overlooked, which could explain the dichotomy between play and learning amongst teachers and children. Pyle and Danniels (2017) identify two preschool teacher’s profiles depending on whether the play is investigated or seen as separate from learning. Clerc-Georgy et al. (2020) propose an alternative view to overcome this dichotomy. In their paper, the authors support the idea of a dialectical relation between play and learning, highlighting that scaffolding should be directed towards the development of play and curriculum at the same time. Scaffolding interventions promote learning and can take place either inside or outside the play (Fleer, 2015, 2017b; Wassermann, 1988). To date, few studies have investigated what preschool teachers do when they seize dialectically mathematical teaching opportunities and pretend play. This will be the focus of this case report describing the practices used by a teacher during a CPRT which takes place in the aftermath of a children-initiated pretend play activity.

Pretend Play and Mathematics From an Historico-Cultural Perspective

Pretend play and mathematics are both cultural and semiotic activities. According to Ernest (2006), a semiotic activity involves the use of signs, the use of rules associated with these signs and the attribution of meaning to the signs. Mathematics share all the component of a semiotic activity as signs are used continually during a mathematical activity (Dijk et al., 2004). Regarding play, Vygotsky points out: “Play is the main path to cultural development of the child, especially for the development of semiotic activity” (Vygotsky, 1930/1984, p. 69, as cited in van Oers, 1994). However, Vygotsky (1966/2016) highlights the need to be cautious with the comparison between pretend play and mathematics through the lens of signs. Indeed, the signs used in play are not specific and identical across the play of children, however, in mathematics, a consensus around the use and meaning of signs has been reached across a community of mathematicians. Hence the importance of not intellectualizing children’s play when considering their relation to semiotic activities.

The change in the meaning of objects and actions is specific to the substitution component of pretend play and is used as an indicator of the maturity of the play (Bodrova & Leong, 2012). The role of the teacher is to sustain the development of this component bearing in mind to decrease the mount of support, allowing the children to take responsibility for this change in meaning (Kravtsov & Kravtsova, 2010). Furthermore, the substitution component of pretend play is the best predictor of performances in mathematics and reading (Hanline et al., 2008). More specifically, results of this study have shown that the more the children are able to substitute objects and actions while pretending, the higher their mathematical performances will be when they reach the age of 8. The hypothesis of the authors is that both activities engage the use of signs. This result shows the importance of developing the substitution component of pretend play, considering the long-term effect associated with the maturity of this component.

The close link between pretend play and mathematics makes it a particularly interesting activity to sustain the development of the mathematical thinking of children. In a study by van Oers (1996), teachers were supposed to ask semiotic questions to children (e.g., “Are you sure?”, “How could you be sure?”) in order to stimulate the mathematical actions of children during a pretend play activity based on a shoe shop scenario. The results show that children initiated different types of mathematical actions such as classification, 1–1 correspondence, measuring, and schematizing. Another result of this study is that teachers can use semiotic questions to seize the mathematical activities of children, which then become mathematical teaching opportunities. This study is of particular interest as it shows that teachers can sustain the mathematical actions during pretend play.

These studies highlight the semiotic nature of the link between pretend play and mathematics. They also reveal the fundamental role of the teacher in seizing opportunities to scaffold mathematical actions and pretend play activities initiated by children. However, they do not take into account how teachers can scaffold dialectically the development of pretend play and the mathematical actions initiated by children simultaneously.

Scaffolding During Pretend Play

According to Wood et al. (1976), scaffolding is the process at stake when a teacher supports a student during the completion of a task too difficult to be solved by the student alone. The three main components of scaffolding are: transfer of responsibility, contingency and fading (van de Pol et al., 2010). Scaffolding refers to the progressive transfer of the amount of responsibility to perform a task that is gradually transferred from the teacher to the student. Meaning that scaffolding is aimed at progressively giving ownership of the task completion to the student. Contingency refers to the adjustment of the support to the current level of the student. According to the clues provided by the students’ answers, the teacher will elaborate an idea on the current understanding of the student and adapt the scaffolding. Fading refers to the decreasing amount of support provided by a teacher to a student. When scaffolding fades, the assistance provided is progressively lessened to allow the student to succeed without support. In order to be characterized as scaffolding, an interaction needs to bring into play these three components (van de Pol et al., 2010).

Scaffolding techniques can be used during an interaction aiming at communicating about the play. It has been shown in the work of Wassermann (1988) and Truffer-Moreau (2020). In the Play-Debrief-Replay (PDR) model, Wassermann (1988) holds the view that play is an area of explorations which can be shared and expanded during a debriefing session. During play, different groups of children explore a scientific material proposed by the teacher. The explorations carried out by the children are used as the basis for the debriefing part. After the debriefing session, a replay session takes place where children can play again, bearing in mind the information discussed during the debriefing. The debriefing session share characteristics with the CPRT described by Truffer-Moreau (2020). A CPRT is a reflexive interaction between a teacher and a group of children, elaborating on the scientific concepts investigated during a child-initiated activity. The author highlights that the CPRT “acts as a pivot between children-initiated activities and adult-initiated activities” (Truffer-Moreau, 2020). The CPRT focuses on scientific concepts explored by children during a free play activity. Compared to the PDR model, the material and the group of children are not restricted during the play activity and the replay session does not necessarily take place directly at the end of the debriefing session. A teacher can decide to set up a CPRT at any time during the play. Thus, the teacher is required to be sensitive to children activities as well as to the dimensions of the curriculum associated with the scientific concept explored. During a CPRT, the teacher scaffolds children’s thinking on the basis of what happened during the children-initiated activity. The teacher guides an interaction involving the group of children based on the scientific concepts explored during the play activity. The CPRT is part of a broader systemic structure called pedagogical structure including training activities and two leading activities, which are play activity and learning activity (Elkonin, 1999; Vygotsky, 1935/1995). In the pedagogical structure, the knowledge holds a central place as it constitutes the core and the binder of all the structure’s components. In the PDR model, a replay session takes place directly after the debrief session. The aim is to allow children to replicate their findings or to test other hypothesis discussed during the debriefing. In the CPRT model, play is included in a broader structure. The teacher can thus decide to put in place a structured activity on the scientific concept seized during the CPRT shortly after the CPRT.

Research Question

The studies presented thus far provide evidence that pretend play constitutes a central activity for children’s development during which mathematical contents appear. These contents can be seized by the teacher to foster their appropriation through scaffolding techniques such as CPRT. However, little is known about the teacher’s practices at stake during a CPRT dealing dialectically with a pretend play activity and a mathematical content seized by the teacher. The aim of this research is to explore in terms of scaffolding the practices used by a teacher who seize mathematical teaching opportunities from pretend play activities during a CPRT. The research question is: What are the practices associated with scaffolding used by a teacher during a CPRT in order to seize mathematical teaching opportunities?

Data

The data are part of a larger study exploring the mathematical teaching opportunities arising from children-initiated activities. This extract has been selected as it is considered to be a CPRT. The classroom is situated in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. The teacher has 7 years of experience in teaching. Eleven children aged between 5 and 6 took part in the activity. The teacher and all of the children’s parents signed the ethic form and the data were recorded according to ethical considerations. For ethical reasons, fictitious names are used in this case report. The researchers acted as observers and did not interact with the children.

Before the free play activity begins, the teacher provided materials (e.g., X-ray pictures, fabrics, big jigsaw pieces made of foam, paper, pens...). During a free play activity, the children initiated a hospital pretend play. They undertook different roles (e.g., receptionist, doctors, patients) and recreated different areas in the classroom (e.g., reception, patient’s house, waiting room). The teacher acted as the doctor and moved between being inside and outside of the play. After approximately 1 h, the teacher gathered the children to do a CPRT. She placed an A3 paper-sheet on the floor in front of the children. In Fig. 1, the drawing of the plan of the hospital partly recreated during the CPRT based on the hospital play activity initiated by children is shown.

Methodology and Analysis

In this case report, a qualitative approach will be used based on the interaction analysis of Jordan and Henderson (1995) and the scaffolding framework analysis by van de Pol et al. (2010). The interaction analysis investigates the orderliness and projectability through the decomposition into units of coherent interactions. This method is particularly useful in studying interactions in a school context as it allows the identification of the different practices at stake during teaching/learning interactions. Derry et al. (2010) suggest focusing on “a particular pedagogical or subject content”. In this case report, a CPRT focusing on the elaboration of the plan of the hospital created by children during a pretend play activity is analyzed. Jordan and Henderson (1995) highlight the importance of identifying the beginning and the end of the interaction to analyze. The definition of a CPRT is used to identify the boundaries of the interaction analyzed. The beginning of the activity takes place when all the children sit down together. The end of the activity takes place when the modality of the activity changes from a collective to an individual activity. The interaction has been transcribed including the gestures of the teacher and the children prior to the analysis.

Results

The analysis reveals four practices used by the teacher to seize mathematical teaching opportunities during a CPRT, which will be detailed below: (1) guiding a two-level intersubjectivity, (2) fostering the development of an imaginary situation, (3) raising awareness on challenges and (4) creating meaning between symbolization in the play and symbolization in a cultural tool.

Guiding a Two-Level Intersubjectivity

At the beginning of the CPRT, the teacher guides a two-level intersubjectivity in order to create a common understanding: an intersubjectivity between the teacher and the children (Björklund et al., 2018), and an intersubjectivity between the children themselves. At the teacher-children level, the teacher is responsive to the children’s answers and ensures that a sufficient intersubjectivity emerges. At the children-children level, the teacher guides the interactions to allow children to share their perspectives, mutualize their knowledge, and reach a common understanding. This two-level intersubjectivity (teacher-children; children-children) is directed towards the adjustment of all of their perspectives on the discussed play activity. The teacher makes room for perspectives to be expressed and orchestrates the discussion to establish a sufficient intersubjectivity at these two-level.

Excerpt: “location of the waiting room”

13 | Teacher: | And then we said that there is the waiting room. The waiting room, where it is? |

14 | John: | [points in the direction of the waiting room in the classroom]. |

15 | Teacher: | Yes, you are right, it is here. So, I will mark it here [delineates with a dark pen a rectangle representing the waiting room on the paper sheet]. So, here, it is the waiting room. |

16 | Children: | Yes. |

17 | Teacher: | Ok. Here, [points the dark rectangle] it will be the waiting room. |

In this excerpt, the teacher asks questions about the location of the hospital’s waiting room created by the children and documents the plan by drawing a rectangle on the paper sheet. This is done systematically for each area every time an agreement is reached. The teacher asks about the location of the waiting room. John points in the direction of the area dedicated to the waiting room during the play activity. As all the children agree, the teacher adds the delineation of the waiting room on the plan. In this excerpt, the plan supports the two level intersubjectivity as it contains information on what is agreed on between the teacher and the children but also between the children themselves.

Fostering the Development of an Imaginary Situation

The second practice requires fostering the imagination of the children while reflecting on the play. To expand the learning at stake, the teacher builds the CPRT on the basis of what happened during the play activity and fosters the imagination of children to encourage them to go further. While doing this, the teacher creates a bridge between play activity and learning (Fleer, 2017a).

Excerpt: “adding a school to the hospital”

40 | Veronica: | And after, me, I know. I know what we are going to do [raises her hand]. Over there, over there [points in the direction of the back of the classroom], it is the classroom, over there over there in the classroom. |

41 | Teacher: | There is a school. But is it part of the hospital or is it another area? |

42 | Veronica: | It’s part of the hospital. |

43 | Teacher: | There is a school in the hospital. |

44 | Veronica: | Yes. |

45 | Oscar: | No. |

46 | Tom: | Yes. There is a school to make the children for example I fell at ski and they are going to teach you how to ski better so that you won’t hurt again. |

47 | Teacher: | Oh ok. [takes a pen to delineate the school area on the paper sheet] |

In this excerpt, Veronica adds a school in the hospital. During the play activity, the children did not create a school which could explain Oscar’s objection. Instead of asking if the school was set up during the activity, the teacher encourages Veronica to give more information about the school. Tom makes a link between the function of a hospital and a school to make a case for Veronica’s proposition. Once the agreement is reached, the teacher adds the new area of the hospital on the plan. The plan thus becomes more complex and supports children as they create meaning. The teacher fosters the imagination of the children by being responsive to their propositions and by encouraging them to capitalize on their knowledge to explore further through imagination.

Raising Awareness on (Potential) Challenges That Can be Resolved Using Mathematical Tools

The third practice used by the teacher while talking about the imaginary situation, is to make children aware of (potential) challenges that can be resolved using mathematical tools. The teacher can also mention an event experienced by the children during the imaginary situation, and discuss the challenges through a mathematical perspective.

Excerpt: “shed light on a challenging situation”

122 | Teacher: | You see now me I can remember well because we just did it now. But the next time, now we will have to tidy the classroom. Next time, if I want to do the same hospital again, how will I do to remember that this was the twine area, this was the reception? |

123 | Charlotte: | So we write. |

124 | Teacher: | Oh. You would like to write. Do you have the place to write re-ce-ption. (insisting on the syllables, showing the place it would take to write the word on the paper sheet) |

125 | Child: | No! |

126 | Charlotte: | So, above it. |

127 | Leo: | Up! Up! |

128 | Teacher: | Ok. Could we draw instead of writing something to remember that this was the reception? |

129 | Children: | Yes! |

In this excerpt, the teacher anticipated the difficulty that children would face when trying to match an area on the plan and its corresponding area in the classroom, when rebuilding the complex hospital they created, if they do not add a coding system to the plan. The teacher raises the awareness on the limit of memory span and the need to find a strategy. Charlotte suggests writing it down and the teacher raises another challenge related to the space required to write down long words. Charlotte insists by saying that it is possible to write above the delimited areas on the plan. Finally, the teacher suggests making drawings associated to each delimited area on the plan. All the children agree with this solution. In this excerpt, the teacher raises awareness on a potential challenge and guides the discussion towards the use of symbolization. The teacher takes the responsibility to shed light on a challenging situation and suggests a solution involving the use of a mathematical tool: symbolization.

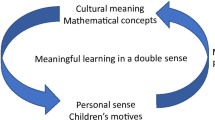

Creating Meaning Between Symbolization in the Play and Symbolization in a Cultural Tool

This practice requires the creation of meaning between symbolization in the play and symbolization in a cultural tool. During pretend play, children substitute the meaning of objects and actions to assign them a new meaning. During the CPRT, the teacher guides the interaction toward the creation of meaning between the substitution during play and the use of symbols in a cultural tool. Children are encouraged to reflect on the symbols they used in the play and expand their abstract thinking to symbols used in cultural tools. Here, the CPRT acts as a bridge between symbolization in the play and symbolization in a cultural tool.

Excerpt: “finding symbols to represent areas on the plan”

130 | Teacher: | What could we draw then? [pointing to the square associated with the reception on the plan] |

131 | Maya: | A computer. |

132 | Teacher: | Oh. Draw a computer. |

133 | Diego: | And a chair. [pointing to the reception area: a chair, and a keyboard on a table] |

134 | Teacher: | And to remember… And a chair. And to remember this? We’ve said that it was the waiting room. |

135 | Emily: | A bed or a chair. |

136 | Teacher: | For example, chairs. |

In this excerpt, the teacher encourages children to find symbols that could be drawn on the plan to remember the function associated with each area delineated on the plan. The teacher asks questions to make the children aware of the challenges that need to be resolved collectively and transfers the responsibility of creating the symbols to the children. The teacher guides the children to move from symbolization in the play to symbolization in the plan. For different areas, children suggested the props used in these specific play areas. To represent the reception area, Maya suggests drawing a computer. Diego adds a chair as there is a chair in front of the table with the keyboard. On the plan, a keyboard and a computer mouse have been drawn to represent the reception (pink). When the teacher asks about the waiting room, Emily suggests a bed or a chair as they created beds and used chairs from the classrooms to represent the waiting room area during the play activity. As beds are already used to represent the patients’ room (yellow), the teacher repeats “chairs”. In the Fig. 1, we can see some iconic signs sharing characteristics with props used in the play. For example, the waiting room is represented by a chair and a table (black). When the teacher creates meaning between symbolization in the play and symbolization in a cultural tool, it scaffolds symbolization.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to identify the practices used to seize mathematical teaching opportunities during a CPRT. The results suggest that the teacher used four different practices sustaining dialectically mathematical and play-related thinking of children during a CPRT taking place after a pretend play activity. The teacher ensures that a sufficient intersubjectivity emerges at two level creating a common understanding of the subject at stake: between the teacher and the children and between the children themselves. The teacher fosters the development of the imaginary situation and raises awareness on challenges. The fourth practice is used to create meaning between symbolization in the play and symbolization in a cultural tool.

During the CPRT, children were encouraged to reflect on the imaginary situation created at a metacommunicative level and using a mathematical perspective. During a CPRT, the teacher undertakes the role of the expert and guides the children through the appropriation of cultural tools while leading a reflexive discussion, which maintains the link between imaginary situation and learning. In this CPRT, the teacher starts a plan of the hospital created by children during a pretend play activity by delineating the areas imaginated by children and then let them individually draw a symbol representing an area. Dijk et al. (2004) found that the first signs used by children often represent a real object. This result highlights the importance of introducing symbolization activities in the early years as they play an important role in the development of the abstract thinking of children. This is in line with the idea stated by Vygotsky (1966/2016) that learnings occur at a social level before being internalized at the individual level. During a CPRT, the teacher guides a discussion to create this dynamic using different practices.

In our study, the findings suggest a role for the teacher in sustaining and scaffolding dialectically pretend play and mathematical activities initiated by children in order to build a cognitive structure (van de Pol et al., 2010). Children’s cognitive structure will build upon the pretend play and mathematical explorations they initiated, as well as the reflexive interactions guided by the teacher. This article adds to the growing body of research highlighting the need to scaffold dialectically pretend play and the scientific concepts explored during an imaginary situation (Fleer, 2017b). The specificity of this study is that a pretend play activity initiated by children could provide the basis for a mathematical reflection guided by the teacher beyond the play activity.

The major limitation of this study lies in the fact that the findings come from a case study. Thus, other practices could exist, which have not been found in our analysis. There is, therefore, a definite need for further studies to explore the practices used by teachers to sustain dialectically the imaginary situation and the mathematical content initiated by children in a larger corpus of CPRT. Although the current study is a case study, the findings suggest that different practices can be used by teachers to seize mathematical teaching opportunities during a CPRT taking place outside of a pretend play activity. The practices found in this article could be used for the initial training of teachers, guiding them through the appropriation of CPRT as a useful tool to foster children’s learnings.

References

Amrar, L., & Clerc-Georgy, A. (2020). Le développement des compétences mathématiques précoces dans le jeu de faire-semblant: le rôle de compétences cognitives et socio-affectives spécifiques. A.N.A.E., 165, 194–201.

Björklund, C., Magnusson, M., & Palmér, H. (2018). Teachers’ involvement in children’s mathematizing – beyond dichotomization between play and teaching. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(4), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2018.1487162

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2012). Le soutien aux gains développementaux des enfants d’âge préscolaire. In E. Bodrova & D. J. Leong (Eds.), Les outils de la pensée: l’approche vygotskienne dans l’éducation à la petite enfance (pp. 211–244). Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Clerc-Georgy, A., Martin, D., & Maire-Sardi, B. (2020). Des usages du jeu dans une perspective didactique. In A. Clerc-Georgy & S. Duval (Eds.), Les apprentissages fondateurs de la scolarité. Enjeux et pratiques à la maternelle (pp. 33–51). Chronique Sociale.

Derry, S., Pea, R. D., Barron, B., Engle, R. A., Erickson, F., Goldman, R., Hall, R., Koschmann, T., Lemke, J. L., Sherin, M. G., & Sherin, B. L. (2010). Conducting video research in the learning sciences: Guidance on selection, analysis, technology, and ethics. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19(1), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508400903452884

Dijk, E. F., van Oers, B., & Terwel, J. (2004). Schematising in early childhood mathematics education: Why, when and how? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 12(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930485209321

Elkonin, D. B. (1999). Toward the problem of stages in the mental development of children. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 37(6), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405370611

Ernest, P. (2006). A semiotic perspective of mathematical activity: The case of number. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 61(1), 67–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-006-6423-7

Fleer, M. (2015). Pedagogical positioning in play – teachers being inside and outside of children’s imaginary play. Early Child Development and Care, 185(11–12), 1801–1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1028393

Fleer, M. (2017a). Play in the early years. Cambridge University Press.

Fleer, M. (2017b). Scientific playworlds: a model of teaching science in play-based settings. Research in Science Education, 49(5), 1257–1278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-017-9653-z

Hanline, M. F., Milton, S., & Phelps, P. C. (2008). A longitudinal study exploring the relationship of representational levels of three aspects of preschool sociodramatic play and early academic skills. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 23(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540809594643

Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis: Foundations and practice. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 4(1), 39–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2

Kravtsov, G. G., & Kravtsova, E. E. (2010). Play in L. S. Vygotsky’s nonclassical psychology. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 48(4), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.2753/rpo1061-0405480403

Pyle, A., & Danniels, E. (2017). A continuum of play-based learning: The role of the teacher in play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Education and Development, 28(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1220771

Seo, K. H., & Ginsburg, H. P. (2004). What is developmentally appropriate in early childhood mathematics education? Lessons from new research. In D. H. Clements & J. Samara (Eds.), Engaging young children in mathematics: Standards for early childhood mathematics education (pp. 91–104). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Truffer-Moreau, I. (2020). Dans la perspective d’une didactique des apprentissages fondamentaux: “La structure pédagogique”, un dispositif au service d’une pédagogie des transitions. In A. Clerc-Georgy & S. Duval (Eds.), Pratiques enseignantes et apprentissages fondateurs de la scolarité et de la culture (pp. 53–69). Chronique Sociale.

van de Pol, J., Volman, M., & Beishuizen, J. (2010). Scaffolding in teacher–student interaction: A decade of research. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9127-6

van Oers, B. (1994). Semiotic activity of young children in play: The construction and use of schematic representations. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 2(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502939485207501

van Oers, B. (1996). Are you sure? Stimulating mathematical thinking during young children’s play. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 4(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502939685207851

van Oers, B. (2014). Cultural-historical perspectives on play: Central ideas. In L. Brooker, M. Blaise, & S. Edwards (Eds.), The Sage handbook of play and learning in early childhood (pp. 56–66). Sage.

Vygotski, L. S. (1930/1984). Orudie i znak v razvitii reb6nka. [Tool and sign in the development of the child]. In L. S. Vygotsky (Ed.), Sobranye Sochinenij Collected works Tome 6 (pp. 6–90). Pedagogika.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1935/1995). Apprentissage et développement à l’âge préscolaire. Société Française, 2(52), 35–45.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1966/2016). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 7(2), 3–25.

Wassermann, S. (1988). Teaching strategies. Childhood Education, 64(4), 232–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.1988.10521542

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 17, 89–100.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the teacher and the children who participated in this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Amrar, L., Clerc-Georgy, A., Dorier, JL. (2024). Preschool Teacher Practices During a Collective Play-Related Thinking: Dialectic Between Pretend Play and Mathematics. In: Palmér, H., Björklund, C., Reikerås, E., Elofsson, J. (eds) Teaching Mathematics as to be Meaningful – Foregrounding Play and Children’s Perspectives. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37663-4_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37663-4_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-37662-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-37663-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)