Abstract

One of the stylized facts in the literature is that the level and quality of entrepreneurship is determined by institutional framework conditions—the so-called rules of the game. In this conceptual contribution, we show that this insight is also key to understand the massive surge in start-up activity after the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe. Our contribution draws on recent work analyzing who decided to start a venture in East Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In this previous work, it was found that many individuals who demonstrated commitment to the anti-entrepreneurial communist regime in the socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR) launched their own new ventures soon after German re-unification. We argue that the previous commitment to communism of post-socialist entrepreneurs reflects a tendency toward rent-seeking, which is a form of unproductive entrepreneurship. Once institutions changed radically, their entrepreneurial efforts were directed toward start-up activity. In the current contribution, we reflect on this evidence and discuss to which extent it can be generalized beyond the East German context.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

One of the most fascinating findings over the course of economic transition from communism to market economy was the massive surge in start-up activity across Eastern Europe (e.g., Smallbone and Welter 2001; Fritsch et al. 2022). Where did all these new entrepreneurs come from? Self-employment was prohibited in socialist planned economies, hardly allowing gaining experience necessary for running a venture (Earle and Zakova 2000). Furthermore, the social acceptance of entrepreneurial behavior was very low (e.g., Wyrwich 2015). This situation is at odds with the empirical observation that many people became entrepreneurs relatively soon after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

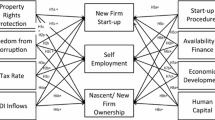

We try to better understand this puzzle by taking a Baumolian (institutional) view on the transition period. Our work also builds on previous own evidence, which shows that people who actively committed to the socialist regime had a particularly high likelihood of becoming self-employed (Sorgner and Wyrwich 2022). While this result may appear puzzling at first, it can be explained by applying Baumol’s argument according to which people allocate their entrepreneurial talent and effort to destructive, unproductive, or productive entrepreneurship depending on the institutional framework conditions. Consider the following train of thoughts:

Starting a firm is an example of productive entrepreneurship while activities such as rent-seeking and corruption are regarded as unproductive or even destructive. When viewing the economic transition through the Baumolian lens, then the massive institutional change should have also changed the attractiveness of different types of entrepreneurship. Starting a firm—productive entrepreneurship—became attractive over the course of economic transition. This increased incentives to re-allocate entrepreneurial effort toward starting a firm. Against this background, the question is what type of activities were these post-transition entrepreneurs involved in before the fall of the Iron Curtain. How did they make use of their entrepreneurial talent and effort before the transition, when productive entrepreneurial activities were not allowed? In Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022), we argue that, before the transition, post-transition entrepreneurs were already involved in unproductive entrepreneurial activities as indicated by their commitment to the socialist regime. This commitment often came along with material rewards, and therefore, it can be seen as a form of rent-seeking, which—according to Baumol—is a form of unproductive entrepreneurship. We observed this pattern for East Germany but did not analyze other Eastern European transition countries. This raises the question as to what extent the results can be generalized beyond the East German context. This question is justified, as the results for East Germany are partly conflicting with findings for other Eastern European countries (e.g., Ivlevs et al. 2021).

In this conceptual contribution, we discuss why the results for East Germany may be different and in how far these findings can be generalized beyond the East German context. We argue that the results can be reconciled by applying the Baumolian institutional perspective. In this respect, we examine different factors—and formulate propositions—that should be considered when explaining the emergence of entrepreneurship in transition economies other than East Germany.

The remainder of this contribution is as follows. In Sect. 2, we discuss the Baumolian perspective on entrepreneurship and summarize the empirical findings in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) for East Germany, while Sect. 3 is devoted to discussing the implications of the results for other transition economies. Section 4 concludes.

2 Institutional Change and Entrepreneurship: The East German Case of Transition from Socialism to Market Economy

The most important argument put forward by Baumol (1990) is that institutions determine how people make use of their entrepreneurial talent and how they direct their entrepreneurial effort. In this respect, market economies provide a fertile breeding ground for productive entrepreneurship (i.e., innovative start-up activity) with the quality of the market institutions being positively linked to the level of this type of entrepreneurship (e.g., Sobel 2008; Stenholm et al. 2013). In contrast, in institutional set-ups where markets played a less important role, like in Ancient Rome or in the early Middle Ages, entrepreneurial effort was more likely to be used for unproductive activities, such as rent-seeking (Baumol 1990). To understand the factors that facilitate such significant changes in the type of entrepreneurial effort, we incorporated Kirzner’s (1973) work into our conceptual framework. Kirzner (1973) argued that alertness is a key characteristic of entrepreneurs, which is defined as a cognitive capability that positively influences both opportunity identification (Kirzner 1973) and opportunity creation (Kirzner 2009) (for an extensive overview and reflection, see Korsgaard et al. 2016). Alertness as a characteristic of entrepreneurs is not specific to market economies. Therefore, alertness can be also applied to the context of institutional change, which helps to identify opportunities emerging from such a change (for details, see Sorgner and Wyrwich 2022).

In Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022), we make the case that the transition from communism to a market economy in Eastern Europe, and in East Germany in particular, is an ideal set-up to study the shift from unproductive to productive use of entrepreneurial talent and effort. While the institutions in communism inhibited productive forms of entrepreneurship, such as start-up activity, the transition to a market economy facilitated new firm formation. We demonstrate empirically that a significant number of new business owners in East Germany revealed strong commitment to the communist regime prior to German re-unification. This commitment can be considered as rent-seeking behavior, as it was associated with material benefits in the centrally planned economy of the communist GDR, which was plagued by shortages.

Assessing an individual’s commitment to the regime retrospectively is a challenging task. Participants in surveys may be reluctant to reveal this sensitive information during a time of change when the personal consequences of their responses are uncertain. For instance, in the context of the GDR, being affiliated with the secret police (Stasi) may have led to material benefits, but it is unlikely that people would openly admit to this, as surveillance activities had a negative impact on the well-being of East Germans and society at large (e.g., Neuendorf 2017; Lichter et al. 2021). Alternative measures, such as party membership or state and military employment, are less accurate indicators of regime commitment. On the one hand, ordinary party membership in the GDR did not necessarily imply high levels of regime commitment (Bird et al. 1998). State and military employment, on the other hand, required specific career decisions and professional specializations, and, thus, cannot be considered a generally accessible strategy for rent-seeking.

Previous literature has shown that telephone ownership can serve to identify individuals who were deeply committed to the communist regime (Bird et al. 1998). In the GDR, telephones were seen as a luxury item due to their scarcity, the hurdles that needed to be cleared to obtain them, and the access to exclusive resources that a telephone line provided (see Sorgner and Wyrwich 2022).Footnote 1 Thus, owning a telephone may have also indirectly facilitated rent-seeking behavior. It should be noted that the decision to grant a telephone line in the GDR was politically motivated (Economides 1997), making it unlikely that those not committed to the regime would become telephone owners. Telephone ownership should not be taken as a sign of general wealth in the GDR. It is important to note that income inequality was low in the GDR.Footnote 2 Thus, participation in rent-seeking activities was focused on obtaining specific, scarce material rewards, not on acquiring wealth.Footnote 3 Telephones were a highly coveted possession, and, thus, an indication of strong commitment to the regime.

At the same time, it should not be expected that all individuals who were committed to the regime and possessed a telephone became self-employed after the transition. Staunch supporters of the regime who sincerely believed in the communist ideology were unlikely to start their own venture after the fall of the Iron Curtain. In Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022), we find that telephone ownership was also prevalent among people who hold value priorities completely opposed to entrepreneurship. More precisely, there is a U-shaped link between telephone ownership and entrepreneurial values indicating that people with either low or high levels of entrepreneurship-facilitating values were more likely to own a telephone. Analogously, not every transition into self-employment should be seen as a shift from rent-seeking activities. Many people started their own businesses out of necessity, as the shock transition resulted in a significant economic decline and elevated unemployment rates (Lechner and Pfeiffer 1993; Brezinski and Fritsch 1995).

Our findings, reported in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022), confirm that participating in leisure activities that reflect regime commitment is positively correlated with telephone ownership. Moreover, we find that individuals who owned telephones in the GDR were more likely to establish a firm after the German re-unification in 1989. They earned higher incomes as entrepreneurs, and their start-ups had longer survival rates. This suggests that they were able to identify and take advantage of business opportunities arising from changes in the system. People with a personality profile conducive to entrepreneurship and a stronger value for autonomy were also more likely to own telephones. These findings remain robust even after controlling for factors such as human capital, wealth, and high-level positions in management or the Party. The key result from this study was that regime commitment beyond assuming a top-tier elite position was positively linked to start-up activity in the post-socialist era.

In sum, institutional change, such as the transition from the socialist to market economy, directs individual entrepreneurial efforts in a different channel. Entrepreneurial alertness seems to be a key characteristic of entrepreneurial individuals. As we have shown here, this holds true not just in market economies but also, for instance, in socialist economies, where it had found its expression in rent-seeking behaviors. Once the rules of the game have changed, entrepreneurial alertness helped these same individuals to start their own business ventures in a market-oriented economy.

3 Can the Evidence for East Germany Be Generalized? Implications for Other Transition Economies

The question arises as to whether the findings in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) are specific to East Germany or if they can be generalized to other transition contexts and even to other situations where disruptive institutional change has occurred. Although each country has its unique cultural, political, and institutional developments over the course of history, there might be similar trends that countries in transition share. In what follows, we will discuss several factors—and make propositions—that need to be considered when generalizing the results obtained for East Germany to other Eastern European transition countries. In doing so, we expand on the discussion that was initiated in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022).

The first factor that needs to be considered is the endogenous development of institutional change. This refers to the extent to which individuals who revealed entrepreneurial effort before the transition were able to shape institutional change. Entrepreneurs have been recognized as agents of change (Schumpeter 1912), and there is ample evidence that entrepreneurship in transition contexts leads to institutional change (Smallbone and Welter 2001; Ahlstrom and Bruton 2010; Douhan and Henrekson 2010; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2011; Zhou 2013, 2017; Kalantaridis 2014). For example, in Eastern Europe, the old top-tier elite could shape the transition process and institutional change to their personal advantage by securing monopoly power and subsidies (e.g., Aidis et al. 2008; Kshetri 2009; Du and Mickiewicz 2016). Many new firms in Eastern European transition countries were founded by the former elite, especially in the early period when the institutional framework was still in the formative stages. Smallbone and Welter (2001) argued that, based on Baumol (1990), these “nomenclature” start-ups can be regarded as unproductive entrepreneurship. An endogenous development of institutional change increases the likelihood of profitable rent-seeking opportunities for the former top-tier elite. Hence, the more the institutional change can be shaped by the nomenclature, the lower is the likelihood of a shift from unproductive to productive entrepreneurship. When trying to apply the findings for East Germany to other post-socialist contexts, it is therefore important to consider the extent to which entrepreneurially alert individuals were able to shape institutional change. In East Germany, this extent was rather low, as the readymade institutional framework of West Germany was introduced in the East (see Brezinski and Fritsch 1995, for details). Hence, the institutional change in East Germany was an exogenous shock, while endogenous institutional change can largely be ruled out. In other transition contexts, it is important to disentangle entrepreneurial opportunities emerging through endogenous institutional change from the opportunities picked up by individuals who had no influence on institutional change. This requires a focus on individuals who committed to the regime but were not in top-tier positions and who started firms in sectors with low interaction with government agencies. This rules out the possibility that network effects from the communist period distort the empirical analysis.

Proposition 1

Entrepreneurial opportunities resulting from an endogenous institutional change decrease the scope for productive entrepreneurship after transition.

The first factor partly links to the second factor which is the post-transition institutional quality. The theory on the role of institutional quality for the level of entrepreneurial activities (Sobel 2008; Stenholm et al. 2013; Chowdhury et al. 2019) predicts that the adoption of well-established high-quality institutions is positively associated with the level of new business formation. In the case of East Germany, the institutional framework of West Germany made starting a business more attractive compared to Eastern European countries where rent-seeking opportunities remained relatively profitable, partly due to the endogenous development of the institutional framework. Thus, controlling for the level of institutional quality would be important in a cross-country analysis including other transition countries. A low level of institutional quality may lead to different results as those found in our assessment of East Germany.

Proposition 2

Institutional change leading to the emergence of high-quality institutions increases the scope for productive entrepreneurship .

A third factor to consider is the historical context, namely pre-communist development. Considering the role of history is of particular importance, as it provides many examples of how institutional conditions shape entrepreneurship, as discussed by Baumol (1990). Historical development is pivotal for understanding institutional differences. In more general terms, Williamson (2000) argues that historical processes shape cultures, which in turn affect the formation and changes in institutional framework conditions. Apart from this long-term perspective, it might be worthwhile to examine the historical level of economic development in a region. The level of pre-war economic development across regions that became later part of the Eastern bloc varied strongly. Certain regions in Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and contemporaneous Poland were highly industrialized before World War II (Tipton 1976; Fritsch et al. 2021). Some of these regions also had high levels of entrepreneurship, and there still persist regional differences in start-up activities. The latter finding is relevant as previous research shows that this empirical phenomenon is explained by a persistence of an entrepreneurial culture that is pre-communist in nature and was not eradicated by several decades of anti-entrepreneurial indoctrinations and entrepreneurship-inhibiting regulations (e.g., Fritsch and Wyrwich 2019). An entrepreneurial culture can be defined as a “collective programming of the mind” (Beugelsdijk 2007, 190) and may endure despite long periods of anti-entrepreneurial policies.

The mechanisms behind the persistence of an entrepreneurial culture are largely unclear, but there are indications that historical success and the size of entrepreneurial households are decisive for shaping a collective memory that supports entrepreneurship (Fritsch and Wyrwich 2023). When the institutional framework becomes favorable for starting businesses, such as after the fall of the Berlin Wall, an existing entrepreneurial culture can facilitate the re-emergence of entrepreneurship. Re-activation of entrepreneurship by means of an entrepreneurial culture is likely to take place if there is an entrepreneurial tradition. Hence, the likelihood of shifting entrepreneurial effort from unproductive to productive activities might be also determined by the prevalence of an entrepreneurial culture that facilitates the re-emergence of high levels of new firm formation. Accordingly, there should be also differences across transition regions when it comes to the re-allocation of entrepreneurial talents and efforts. Hence, it is important to consider pre-socialist levels of economic development and entrepreneurship when conducting empirical assessments. The results found in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) may differ for other transition economies in that many East German regions had a strong pre-socialist industrial and entrepreneurial tradition.

Proposition 3

Pre-communist institutions , and particularly the presence of entrepreneurial culture, facilitate productive entrepreneurship after transition.

Another factor is the geographic and cultural proximity of East Germany to West Germany, which facilitated role model effects during the shift from communism to market economy. Role model effects are a known factor in promoting entrepreneurship (e.g., Bosma et al. 2012). In the case of East Germany, it might have already been relevant before the German re-unification. Slavtchev and Wyrwich (2023) find that East German regions that had access to West German TV had higher levels of entrepreneurship, and individuals being exposed to TV had a higher propensity to start firms. After re-unification, role model effects via direct contacts with West Germans may have also helped to become an entrepreneur. The entrepreneurship-facilitating role model effect due to proximity to West Germany made the re-allocation of entrepreneurial talent smoother. Another advantage of the proximity to West Germany was the access to resources (e.g., subsidies), compared to Eastern Europe countries where there was no unification with an established market economy. Proximity to West Germany also facilitated social capital formation.

Social capital is also a key factor for start-up success (e.g., Kim and Aldrich 2005). In the GDR, active commitment to the regime cultivated social capital that could have played a vital role in the success of ventures following the regime change. The joint exposure to an authoritarian regime, communist ideology, and the socialist command economy had a negative impact on various other factors that contribute to entrepreneurial success. Among the most affected characteristics, one could mention industry experience (Wyrwich 2013), the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship-relevant human capital (e.g., Fritsch and Rusakova 2012), and general entrepreneurial skills (e.g., customer orientation, financial skills, critical thinking). These factors required adaptation during the transition, for instance, because work routines in a state-owned company were vastly different from those in market economy firms including start-ups (Johnson and Loveman 1995). On the other hand, social capital might have played an important role. The findings in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) demonstrate that weak social ties (associational activity) were more important than strong social ties (friends and family) for obtaining a telephone. Hence, forming social capital through weak ties could be a possible channel through which rent-seeking behavior was eventually rewarded. Thus, telephone ownership reflects the ability to form weak social ties, which is another important factor for successful entrepreneurship (Kim and Aldrich 2005). Thus, social capital acquired in the socialist context may be an important channel for the link between telephone ownership in the GDR and successful start-up activity after 1989. In sum, proximity to West Germany could have facilitated the re-allocation of entrepreneurial talent and effort in post-socialist East Germany due to its positive impact on the formation of social capital.

Proposition 4

Geographic and cultural proximity of a post-socialist economy to an established market economy could be expected to predict the level of productive entrepreneurship after the transition.

The final component that needs to be considered when analyzing the re-allocation of entrepreneurial effort and talent in other transition contexts is the measurement of entrepreneurial effort during the communist period. Ivlevs et al. (2021) found that former communist party members who selected into entrepreneurship did so mainly out of necessity due to, for instance, blocked mobility (e.g., discrimination in the labor market). Often, they were less successful as entrepreneurs. This contrasts with our results, reported in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022), that people who were committed to the communist regime were more successful business founders. We believe that our findings are not in conflict with the results reported in Ivlevs et al. (2021). Our focus is not on party members, but on a stronger commitment to the regime as a form of rent-seeking behavior, which is reflected by access to material rewards, such as a telephone. Some party members may have joined the party for ideological reasons, making it unlikely that they will ever become self-employed. Furthermore, as Bird et al. (1998) point out, becoming a party member did not require a big deal of commitment. Our empirical measure—access to material rewards, such as a telephone—reflects a much stronger commitment than party membership. This does not mean that the same measure can be applied in other transition contexts. Depending on the country-specific context, there might be more suitable measures to capture regime commitment. It is an empirical challenge to find comparable measures in other transition economies that accurately capture this level and type of commitment to the regime. It might even be an impossible challenge to find a universally valid measure. It is important to replicate our analysis in other transition contexts and to compare the results with our findings for East Germany.

Altogether, there are several factors that need to be considered if we want to understand whether the results that we found for East Germany can be generalized to other transition countries. These factors include finding a comparable measure for commitment to the communist regime revealing rent-seeking behavior (unproductive entrepreneurial efforts), pre-socialist historical developments, post-socialist institutional quality as well as the degree to which post-socialist institutions emerged endogenously, and the geographic and cultural proximity of a transition economy to an established market economy. The case of East Germany is surely not a representative case for other East European transition countries regarding the factors mentioned above. Exogenous entrepreneurial opportunities, the geographic and cultural proximity of East Germany to West Germany, favorable pre-socialist conditions, and the quality of institutions after the transition are certainly the reasons for the results in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) to be an upper-bound estimate. Nevertheless, the considerations presented here may be helpful in explaining differences in the level and the quality of entrepreneurial activities among the East European transition economies.

4 Concluding Remarks

In this contribution, we analyze the conditions for the emergence of productive entrepreneurship in transition economies after an institutional change. We build on the seminal work by Baumol (1990), who proposes that entrepreneurial talent is bound to certain individuals who direct their effort to productive, unproductive, or destructive entrepreneurship depending on the institutional framework. This micro-foundation of his work received relatively little attention in the literature, which mostly focused on the macro-level implications of his theory (Sobel 2008; Stenholm et al. 2013; Chowdhury et al. 2019). Furthermore, the role of alertness to entrepreneurial opportunities (Kirzner 1973, 2009) in non-market economies was also largely ignored.

Our results in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) show that a material reward for committing to an anti-entrepreneurial regime—here, telephone ownership—is positively linked to launching an own venture after transition. This suggests that people with pronounced alertness to entrepreneurial-arbitrage opportunities immediately redirected their entrepreneurial efforts from rent-seeking in the GDR toward becoming their own boss in reunified Germany. Our results indicate that such start-ups were less likely to be driven by necessity and were more successful than other start-ups.

Against this background, the question emerges as to what extent the results can be generalized beyond the specific East German context. The aim of the present contribution is to highlight the context factors that need to be considered in any empirical assessment for other transition contexts in order to make the results comparable to the East German case. Thus, we make several propositions that could be tested empirically in the context of other transition economies. It is an empirical challenge to find a comparable measure for commitment to the communist regime that reveals unproductive entrepreneurial efforts, collect data on pre-socialist historical developments, post-socialist institutional quality, and the degree to which post-socialist institutions emerged endogenously. Finally, the geographic and cultural proximity of a transition country to an established market economy could facilitate the possibilities for reallocating entrepreneurial effort and talent into a more productive channel. Therefore, the results we find for East Germany in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) are surely an upper-bound estimate.

Apart from analyzing transition from a socialist to a market economy, as described in the previous section, future research should analyze other dramatic shifts in institutional environments that may have occurred in other countries. Another approach would be to study individual entrepreneurial behavior before, during, and after catastrophic events like civil wars that brought about an exogenous change to the environment (e.g., Paruchuri and Ingram, 2012; Bullough et al. 2014; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2017; Dimitriadis 2021). Another avenue for future research could be the influence of institutional structures on the link between individual characteristics and entrepreneurial outcomes (e.g., Boudreaux et al. 2018; Boudreaux et al. 2019; Schmutzler et al. 2019; Fritsch et al. 2019).

Our research highlights how individuals respond to a dramatic change in the institutional environment. There are several important research questions that emerge from our study. For example, how do institutional arrangements affect the type of entrepreneurial activity people choose? Future research could apply more narrow definitions of productive entrepreneurship, for example, related to innovation. Future research on institutions and destructive entrepreneurship would be of interest as well. Finally, further research on the impact of institutional change on entrepreneurial behavior across diverse contexts and historical periods will deepen our understanding of the link between institutions and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort and talent.

Notes

- 1.

In 1989, there were approximately 1.8 million telephone lines in the GDR compared with 30 million in the FRG (see Leister 1996).

- 2.

The average net income of individuals with a university degree was about 15 percent higher than that of blue-collar workers, compared to 70 percent in the FRG. Intersectoral income differences were minimal, too (Alesina, Fuchs-Schündeln 2007).

- 3.

These arguments notwithstanding, there are also several further aspects that need to be considered when using telephone ownership. For example, people in certain professions like medical doctors may have had a telephone for different reasons. We control for the occupation and the industry people were active in and run further robustness checks in Sorgner and Wyrwich (2022) to dispel concerns regarding the validity of our measure.

References

Ahlstrom D, Bruton G D (2010) Rapid Institutional Shifts and the Co–evolution of Entrepreneurial Firms in Transition Economies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34: 531–554

Aidis, R et al. (2008) Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: A comparative perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 23: 656–672

Alesina A, Fuchs-Schündeln N (2007) Goodbye Lenin (or not?): The effect of communism on people’s preferences. American Economic Review, 97: 1507–1528

Baumol W J (1990) Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98: 893–921

Beugelsdijk S (2007) “Entrepreneurial culture, regional innovativeness and economic growth”. Journal of Evolutionary Economics. 17(2): 187–210.

Bird E J et al. (1998) The income of socialist upper classes during the transition to capitalism: Evidence from longitudinal East German data. Journal of Comparative Economics, 26: 211–225

Bosma N et al. (2012) Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2): 410–424

Boudreaux C J et al. (2018) Corruption and destructive entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 51: 181–202

Boudreaux C J et al. (2019), Socio-cognitive traits and entrepreneurship: The moderating role of economic institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34, 178–196

Brezinski H, Fritsch M (1995) Transformation: The shocking German way. MOCT-MOST: Economic Policy in Transitional Economies, 5: 1–25

Bullough A et al. (2014) Danger Zone Entrepreneurs: The Importance of Resilience and Self-Efficacy for Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 38: 473–499

Chowdhury F et al. (2019) Institutions and Entrepreneurship Quality. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 43: 51–81

Dimitriadis S (2021) Social capital and entrepreneur resilience: Entrepreneur performance during violent protests in Togo. Strategic Management Journal, 42: 1993–2019

Douhan R, Henrekson M (2010) Entrepreneurship and second-best institutions: Going beyond Baumol’s typology. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 20: 629–643

Du J, Mickiewicz T (2016) Subsidies, rent seeking and performance: Being young, small or private in China. Journal of Business Venturing, 31: 22–38

Earle J S, Zakova Z (2000) Business Start-ups or Disguised Unemployment? Evidence on the Character of Self-Employment from Transition Economies. Labour Economics, 7: 575–601

Economides S (1997) Modernization of Telecommunications in the Former GDR. In Welfens P J J, Yarrow G (eds.) Telecommunications and Energy in Systemic Transformation International Dynamics. Deregulation and Adjustment in Network Industries, 143–152, Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg

Fritsch M, Rusakova A (2012) Self-Employment after Socialism: Intergenerational Links, Entrepreneurial Values, and Human Capital. International Journal of Developmental Science, 6: 167–175

Fritsch M et al. (2019): Self-employment and well-being across institutional contexts. Journal of Business Venturing, 34: 105946

Fritsch M, Wyrwich M (2019). Regional Trajectories of Entrepreneurship, Knowledge, and Growth—The Role of History and Culture. Cham: Springer

Fritsch M et al. (2021) Historical roots of entrepreneurship in different regional contexts—The case of Poland. Small Business Economics, 59: 397–412

Fritsch M et al (2022) The Long-run Effects of Communism and Transition to a Market System on Self-Employment: The Case of Germany. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, forthcoming

Fritsch M, Wyrwich M (2023) How is Regional Entrepreneurship Transferred over Time? The Role of Family Size and Economic Success. mimeo.

Henrekson M, Sanandaji T (2011) The interaction of entrepreneurship and institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7: 47–75

Ivlevs A M et al. (2021) Former Socialist party membership and present-day entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 57: 1783–1800

Johnson S, Loveman G (1995) Starting Over in Eastern Europe: Entrepreneurship and Economic Renewal. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press

Kalantaridis C (2014) Institutional change in the Schumpeterian-Baumolian construct: Power, contestability and evolving entrepreneurial interests. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 26: 1–22

Kim P H, Aldrich H E (2005) Social capital and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 1: 55–104

Kirzner I M (1973) Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Kirzner I M (2009) The alert and creative entrepreneur: a clarification. Small Business Economics, 32: 145–152

Korsgaard S et al. (2016) A tale of two Kirzners: Time, uncertainty and the “nature” of opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40: 867–889

Kshetri N (2009) Entrepreneurship in post-socialist economies: A typology and institutional contexts for market entrepreneurship. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 7: 236–259

Lechner M, Pfeiffer F (1993) Planning for self-employment at the beginning of a market economy: Evidence from individual data of East German workers. Small Business Economics, 5: 111–128

Leister R-D (1996) The Significance of Telecommunications for the Modernization of National Economies. Society and Economy in Central and Eastern Europe, 18: 56–77

Lichter A et al. (2021) The Long-Term Costs of Government Surveillance: insights from Stasi Spying in East Germany. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19: 741–789

Miller D, Le Breton-Miller I (2017) Underdog Entrepreneurs: A Model of Challenge–Based Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41, 7–17

Neuendorf U (2017) Surveillance and control: an ethnographic study of the legacy of the Stasi and its impact on wellbeing. Doctoral thesis

Paruchuri S, Ingram P (2012) Appetite for destruction: the impact of the September 11 attacks on business founding. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(1): 127–149

Schmutzler J et al. (2019) How Context Shapes Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as a Driver of Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Multilevel Approach. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 43: 880–920

Schumpeter J A (1912) Die Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot

Smallbone D, Welter F (2001) The distinctiveness of entrepreneurship in transition economies. Small Business Economics, 16: 249–262

Sobel R S (2008) Testing Baumol: Institutional quality and the productivity of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 23: 641–655

Sorgner A, Wyrwich M (2022) Calling Baumol: what telephones can tell us about the allocation of entrepreneurial talent in the face of radical institutional changes, Journal of Business Venturing, 37: 106246

Stenholm P et al. (2013), Exploring country-level institutional arrangements on the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Business Venturing, 28: 176–193.

Slavtchev V, Wyrwich M (2023) The effects of TV content on entrepreneurship: Evidence from German unification. Journal of Comparative Economics, forthcoming

Tipton F B (1976) Regional Variations of Economic Development of Germany During the Nineteenth Century. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press

Williamson O E (2000) The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38: 595–613

Wyrwich M (2013) Can socioeconomic heritage produce a lost generation with regard to entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 28: 667–682

Wyrwich M (2015) Entrepreneurship and the intergenerational transmission of values. Small Business Economics, 45: 191–213

Zhou W (2013) Political connections and entrepreneurial investment: Evidence from China's transition economy. Journal of Business Venturing, 28: 299–315

Zhou W (2017) Institutional environment, public-private hybrid forms, and entrepreneurial reinvestment in a transition economy. Journal of Business Venturing, 32: 197–214

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sorgner, A., Wyrwich, M. (2024). The Re-allocation of Entrepreneurial Talent During Transition from Socialism to Market Economy: Some Conceptual Thoughts. In: Günther, J., Jajeśniak-Quast, D., Ludwig, U., Wagener, HJ. (eds) Roadblocks to the Socialist Modernization Path and Transition. Studies in Economic Transition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37050-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37050-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-37049-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-37050-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)