Abstract

The UK was the birthplace of industrial-scale steelmaking, but the industry has faced significant challenges throughout its history. As the industry continues to advance, workers and their communities must be supported through that change to deliver a just transition. This chapter tells the story of the UK steel industry from the point of view of Community, the largest and leading trade union representing steelworkers in the UK. Beginning from the earliest history, and continuing to the present day, this chapter demonstrates the historic and continued importance of steel to communities in the UK. The chapter aims to provide a broad overview of the relationship between trade unions and steel industry. It highlights case studies where failure to act has led to the loss of steel making and discusses the importance of tripartite dialogue to protect and preserve communities and jobs, particularly during periods of social and technological transformation such as those discussed in this volume.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

I am grateful to Roy Rickhuss and Alasdair McDiarmid for their time in sharing their experiences of the steel industry. I would also like to thank Maya Ilany and Kate Dearden for fruitful discussions and comments that led to the completion of the chapter.

The UK steel industry supported 33,400 direct jobs in 2019, a number which has declined over time—there were over 320,000 jobs in the industry in 1971 (Hutton et al., 2021), yet the industry has remained of vital importance to the communities that depend on it. Steelmaking has roots in many regions across the UK: in Scotland, the Northeast, Wales, Yorkshire and the Humber, and the West Midlands. After years of under-investment, many sites have closed, especially those in Scotland and the Northeast, leaving their communities devastated.

This chapter sets out the story of the steel trade union, Community in the UK, from its earliest history to the present day, with a particular focus on the present day and the challenges of net zero and decarbonisation. The UK steel industry has faced successive waves of industrial change, weathering political changes as governments changed between the Conservative and Labour parties, and global changes including wars, climate change and a changing industrial landscape. The lessons of the UK steel industry have implications for national policy (and wider lessons for the UK and Europe) and in particular the approach to and importance of just transition, and the need for coordinated action to support industries and communities.

2 Early History

To turn iron ore into useful products like food packaging, bridges, and hospital beds, it must be transformed by skilled application of heat, carefully controlling the ration of iron, carbon, and waste material. For the earliest steelworkers, without technology to heat iron to melting point, the challenge was to incorporate carbon into the wrought iron they had smelted to make a stronger material. Evidence suggests they could already do so in the late Iron Age, Roman and early Medieval times (Lang 2017: 863). It took until the eighteenth century to take the first steps towards the European steel industry as we know it today. First, much higher temperatures were reliably achieved through the use of coking coal and with this development the challenge was inverted: how to take high carbon pig ironFootnote 1 and reduce the percentage of carbon. AdvancesFootnote 2 such as crucible steelmaking (Fabián 2018) gave greater precision over this balance, and allowed the creation of stronger and less brittle steel, with particular success in the city of Sheffield. A step change came in 1864 when the first Bessemer converter was used commercially, allowing steelworkers to inexpensively decarburize steel (the ‘Bessemer process’). These developments made industrial-scale blast furnace steelmaking possible from the middle of the nineteenth century.

As the sector industrialised the nature of work in the industry shifted. No longer could an individual craftsperson (or group of craftspeople) set up for themselves because of the capital required (Pugh, 1951: 9). Whilst work in the steel industry remained skilled the transition led to new demands for workforce organisation (Evans, 1998: 155). In the nineteenth century, the UK steel industry was world-leading, driving the industrial revolution. By 1875 the UK produced almost half of the world’s pig iron and 40% of the world’s steel (Coats, 2020, p. 35), much of it produced in the Yorkshire region. In this context, unions began to spring up, usually on a small scale. In 1842 an early unionist, John Kane, tried unsuccessfully to form a union of steelworkers (Pugh, 1951: 32). Kane was eventually to succeed at founding a trade union, the Amalgamated Malleable Ironworkers, 20 years later (Pugh, 1951: 11). Early unions were small and specialised and tended to wax and wane as strikes or wage negotiations took place (Pugh, 1951: 11). It was these early unions that were later to become the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation (ISTC).

Conditions in the early steel industry are described by Arthur Pugh where he reflects on his own first job in the industry in 1894, transferring an ingot from the furnace onto rollers:

‘… if by accident one of the narrow wheels of the bogie happened to slip between two of the iron floor plates, there would be a sudden stop, the ingot would fly off the bogie, up would go the handle, and unless the man at the end was smart he would be taken off his feet. The thing to watch was when the handle came back or you might get a bang on the head which, in the most lucky event, would leave a painful impression’ (Pugh 1951: 17)

He was paid 4 shillings 6d. a shift for this dangerous workFootnote 3 (Pugh 1951: 17). For people working in such conditions (and with the constant risk of wage rollbacks) unionisation was a necessity.

3 The Twentieth Century

A key challenge for the movement as the twentieth century dawned was inter-union competition. Despite typically specialising to represent specific types of workers, unions were regularly in conflict. This drove a desire for unions in the industry to unify. The first step towards this goal came in 1912 when the Steel Smelters’ Union and the National Amalgamated Society of Enginemen, Cranemen, Boilermen, Firemen and Electrical Workers fused together (Pugh 1951: 21). Then, in 1916, the British Steel Smelters, Mill, Iron and Tinplate Workers, the Associated Iron and Steel Workers of Great Britain, and the National Steelworkers Association, Engineering and Labour League carried out successful ballots to join into a confederation, known as the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation (ISTC), now Community.

The ISTC had an unusual structure whereby a central association, would exist in parallel to the founding unions. Requests for transfers to the central association were higher than anticipated, and new members—including those in roles that were not traditionally unionised, such as chemists—applied to join the union in significant numbers. By the end of December 1917, there were 49,166 members of the central association, of whom 26,808 were new members, and 22,358 had transferred (Pugh 1951, p. 263). Despite this success, the ISTC did not succeed in attracting all the unions it had wanted to. The Blast-Furnacemen’s federation pulled out of talks in 1916, and two other unions failed to secure the majority needed in the ballot.

Meanwhile, the steel industry was stretched by the war effort, facing the imperative to produce as much as possible. Output increased to 10,000,000 tonnes per year in 1918 (Pugh 1951, p. 264). The war also saw shortages of steelworkers as men were called up to the front and an increasing number of women entered into the workforce (Pugh 1951: 266). At that time trade unions were instrumental in improving conditions in the steel industry. A key example is the pathbreaking 1919 ‘Newcastle agreement’ which set out the principle of 8-hour shifts. The steel industry was unusual in that the higher paid men agreed to take a pay cut to meet the costs of the third shift being brought on board (Pugh 1951: 285). Debates about the 8-hour day continued throughout the 1920s, but though there were to be some rollbacks the principle was firmly established, and throughout its history the ISTC would continue to advocate for reasonable restrictions on working time (Upham 1997: 239).

As the war ended, demand for steel was reduced. During the 1920s the union and the industry both struggled. The UK steel industry was facing stiff competition, not least because the reparations that Germany was required to pay under the Treaty of Versailles included providing coal for free to France and Belgium (Peace Treaty of Versailles 1919), whose steel industries became significantly more competitive. Though wages in the steel industry were rising from 1921, unemployment was high. Of £112,926 of expenditure by the central association, in the 12 months to December 1920, £102,721 was unemployment benefitFootnote 4 (Pugh 1951: 318).

The ISTC participated in the 1926 national strike, in sympathy with locked out coalminers, perhaps reflecting that mining strikes hurt the coal-dependent steel industry. Though steelworkers felt a great deal of solidarity for the striking miners, the ISTC was critical of the leadership of the mineworkers’ union (Pugh 1951: 402–403). Government reaction to the strike was severe: the anti-trade union backlash culminated in the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act of 1927 (Novitz 2007: 494), later described by a Labour MP as ‘a vindictive Act, and one of the most spiteful measures that was ever placed upon the Statute Book’ (HC Deb (1931) cols 347–348). The act outlawed secondary strikes, made it a criminal offence to participate in unlawful strikes and placed limits on political levies collected by unions.

As the decade closed, the Labour government won a general election in 1929 and sought to rationalise the steel industry. An inquiry was carried out and a delegation visited France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, and Czechoslovakia. The conclusion was that ‘in general wages and conditions of employment were inferior in the countries visited’ (Pugh 1951: 456) but the committee sought to learn from best practice abroad. Before progress could be made with reorganisation, the pressures of the Great Depression caused the Government to collapse. A National Government, with representatives of all parties, was formed in its place and would remain in place until the outbreak of the Second World War.

Economic conditions improved over the 1930s, in part due to Roosevelt’s New Deal Policies in the USA. In 1934 ISTC membership was up a little, from 41,946 in 1931 to 54,540 (Pugh, 1951, p. 503) and a few years later in 1937 the steel industry appeared to be in good condition. However, even with relative prosperity, there were groups left out. In March 1937 an article in the steelworkers’ journal, Man and Metal, argued for the sharing of work in the tinplate trade, asserting that ‘every possible means of persuasion have been tried to make the men who are working in the fully occupied plants realise that the full employment they enjoy is only possible at the expense of their fellow Trade Unionists who are left derelict outside the closed works gates’ (Pugh, 1951, p. 505). Nevertheless, the spirit of partnership with industry for which the ISTC prided itself was demonstrated well in Sheffield in 1939, when the employer Firth-Vickers had visited the USA and been alarmed by the state of competition it would face in the stainless-steel industry. The employer called a meeting with union officials explaining what he had seen—it was reported that the union representatives offered ‘intelligent’ and ‘technical’ questions (Pugh, 1951: 543).

4 World War II and Beyond

The steel boom of the 1930s was in part in response to the evidence of Germany’s re-arming and fears of war. Consumption of steel was rising, particularly special steels from Sheffield which were used for plane engines (Pugh 1951: 542). The ISTC had 97,476 members by the end of 1940, (still short of peak membership of 124,000 in 1920) but certainly much improved on the depression years (Pugh 1951: 546). When war broke out, the steel industry was classed as essential and protected by reserved occupations. Essential works orders prevented affected workers from changing occupation but did provide them with a guaranteed wage (Pugh 1951: 558). Man and Metal expressed support for this policy and hope for what the post-war era would bring: ‘the opportunities the post-war world will offer for social advance will be unique in the history of mankind’ (Pugh 1951: 558).

By May 1942 confederation membership of the ISTC exceeded 115,500 (Pugh, 1951, p. 56). There were 15,000 steelworkers from the heavy section alone serving in the army and the steel industry was recruiting women to take on these roles (Pugh 1951: 562). These ‘women of steel’ remain a source of pride for Community. Questions addressed by the ISTC at the time included the question of whether workers in hot and thirsty jobs should be accorded extra sugar rations for their tea. There was a three-day strike at Llanelli because maintenance workers were not offered the supplementary sugar given to those on hot works (Pugh, 1951, p. 565)—quite the contrast from the subject matter of earlier disputes, but reflecting war-time concerns!

As the war ended, the trade union backed Labour Party won a landslide victory in the 1945 general election and in 1946 a proposal for the nationalisation of the steel industry was put forward. The incoming Labour government also finally repealed the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927, although it was not until 1951, when wartime regulations were finally lifted, that the status quo returned (Novitz 2007: 494). In 1949 the Iron and Steel Corporation of Great Britain was formed, nationalising the steel industry. Both union and industry were flourishing. The union was headed by a strong executive which alone could authorise strikes, and to whom officials reported. The most significant problem for the industry at this time was keeping up with demand, high both domestically and internationally (Upham 1997: 6).

From this time, a rather unusual dispute resolution mechanism was developed, which persisted for many years. A ‘neutral committee’ would be established containing two representatives for either side of the debate. None of the parties involved would work at the firm relevant to the dispute; such transparency quite regularly ensured swift resolution of issues (Upham 1997: 7). These structures, established under a nationalised industry, were retained as the industry came into and out of private hands, resulting in relatively strong and persistent industrial relations structures, in stark contrast to the oscillating ownership structure of the steel industry, which privatized in 1953 (Upham, 1997: 27) and renationalised in 1967. Unfortunately, failure to adequately invest in the industry characterised both models of ownership throughout the twentieth century, concerning steelworkers whose industry was facing increased competition from abroad.Footnote 5 Though industrial steelmaking was born in Britain, her dominance of the trade was by this stage long gone.

Roy Rickhuss, General Secretary of Community Union since 2013, argues that debates about the merits or demerits of nationalisation have long failed to account for the constant pace of investment and technological change required in the industry to maintain profitability. In a privatised industry, when the hard times come there are motives to get challenging businesses off the balance sheet. In the public sector, industry must compete for state investment with health and education.Footnote 6

5 Modern History

By the 1970s, the steel unions were negotiating from a position of strength with the British Steel Corporation. But the steel industry itself was not strong, running at a loss. Upham describes a ‘long agony of steel’ beginning at this time (Upham 1997: 2). In 1979 Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, bringing an end to the post-war consensus where political parties in the UK were largely in agreement on major issues such as close regulation of industry and the welfare state. Thatcherism advocated free markets, deregulation, privatisation, and sought to make labour markets more ‘flexible’ including through marginalising trade unions. Thatcher’s battles with the coal mining unions are well known in the UK, where there was a yearlong miners’ strike from 1984−1985, which was ultimately unsuccessful. Fewer people, however, are aware of her earlier conflict with steelworkers. Though there was a gathering threat to jobs in the steel industry (Upham 1997: 127), when the steel strike broke out it was about pay.

It was the view of the unions that the government had provoked the strikes. Government documents from January 1980 show that Bill Sirs of the ISTC had told the Prime Minister that it ‘seemed to him that the Prime Minister and Sir Keith Joseph (Secretary of State for Industry) were repeating BSC’s view of the dispute, so much so that it had seemed to him that there might have been a meeting between Ministers and the corporation’ (The National Archives (TNA) PREM19/308 f38, 1980). There was a widespread view that the pay offer, in the context of 17.99% inflation (Office for National Statistics, 2022) was deliberately and provocatively low. Many in the industry at the time believed that the Prime Minister herself was not looking for a strike, but that there were others in the Cabinet seeking to provoke action from steelworkers.Footnote 7

The steel strike lasted three months, but steelworkers suffered substantial hardship during that time. The timing of the dispute was not in the workers’ favour, as steel was stockpiled over the winter. It’s said that Bill Sirs, at the time General Secretary, was in his office in Gray’s Inn Road during a demonstration in London. Striking steelworkers, who believed that the union was not acting sufficiently to represent its members’ interests, barged into the office and confronted the General Secretary.Footnote 8 At the time questions of solidarity were central; no surprise given the interconnectedness of the steel industry and the mining industry. Whilst such political messages were of paramount importance to the ISTC’s staff and NEC (National Executive Committee), the level of importance to the lay steelworker was less significant.

The dispute around pay was eventually resolved with an 11% increase on gross earnings and a 4.5% minimum bonus guarantee (Upham, 1997, p. 147). However, Roy Rickhuss, a young steelworker during the dispute, argues that the conflict had always been more substantial than that, and was fundamentally about restructuring.Footnote 9 Though there was a theoretically successful resolution of the dispute, there were plant closures both before and after the strike. This cut the steel workforce dramatically, with deep human cost (Smith, 2018; Beebee, 2020).

The industry was privatised for the final time in 1988, with British Steel Corporation listing publicly as British Steel Plc (Upham 1997: 217–18). However, industrial relations remained broadly well-structured thanks to legacy institutions that continued despite privatisation. As well as strong Dispute Resolution committees, a ‘bible’ of agreements known as ‘The Heritage’ gathered together the dozens of agreements that had been made between the unions and the government. This set out a framework upon which industrial relations were conducted.Footnote 10

By the late 1980s, ISTC membership seemed to have stabilised at between 41,000 and 42,000 (Upham, 1997, p. 228), about a third of its peak. But the worst reductions in headcount were yet to come. In the winter of 1989, the first signs of trouble in the economy were sighted. In 1990 a spate of closures struck the industry across all regions including the steel and tube works at Clydesdale in Scotland, FH Lloyd Engineering Steel in the West Midlands, Raine and Co. in the Northeast, and Brymbo in Wales (Upham 1997: 235). Then, in May 1990 British Steel announced plans to shut the Ravenscraig hot strip mill in Scotland, which was once the largest such mill in Western Europe, would lead to a loss of 770 jobs in a steel-focussed community (Upham 1997: 236). However, events were advancing, and market forces placed the whole of the steelworks at threat. In 1992 the Ravenscraig works closed in its entirety (Upham 1997: 237). This was partly driven by the economic climate, but many in the ISTC saw this as punishment by Thatcher for the earlier strike. Ravenscraig represented the end of steelmaking in Scotland, and the loss, not only of livelihoods, but of an industry which engendered a deep sense of identity and pride (Moss, 2001).

Despite this challenging environment, there were some opportunities for the ISTC to grow, including through amalgamation. On the 22nd of February 1991, the Amalgamated Society of Wire workers formally merged with the ISTC following a successful ballot (Upham 1997: 233). The ISTC was also becoming more democratic. In 1993 Keith Brookman became the first General Secretary of the ISTC to be elected by a ballot of the membership (Upham 1997: 248). In 1997 the New Labour government swept into power. Whilst much legacy anti-trade union legislation was retained, the Blair government did not bring in further legislation and developed the revised Central Arbitration Committee (CAC) process through which recognition for trade unions could be secured (Simpson, 2007: 289) making it easier for workers to secure representation.

A key development at this time was the merger of British Steel Plc and Koninklijke Hoogvens, a Dutch company, in 1999 to form the Corus Group. The main disputes at this time were around plans to bring together the engineering and production teams. For the unions this caused two kinds of problems. First, management sought to impose headcount reductions, and second, the move created a recurrence of inter-union conflict.Footnote 11 Though there were multi-union collective bargaining arrangements, which continue to the present day, team working brought about significant conflict as members from the craft unions would be supplanting production workers under this model.

Other blows also struck the industry, especially in Wales. In 2001, the Heavy End at Llanwern closed for good and in 2002 Ebbw Vale steelworks closed (Stroud and Fairbrother 2012: 655). Though the remaining part of the Llanwern plant has survived, it has done so with a fraction of previous employment levels (Stroud and Fairbrother 2012: 655). A visitor to Ebbw Vale can immediately note the impact the steel industry has had on the town: even the houses were built by the British Steel Corporation. For Roy Rickhuss, without steel, it is ‘a town without a heart’.Footnote 12 However, some struggling businesses were rescued: for example, in 2003, Allied Steel and Wire, based in Cardiff, which had historically been a private company was bought out of receivership by CELSA, a Spanish company.

In response to plant closures, the Steel Partnership Training scheme was set up. Later renamed Communitas, this arm’s length body supported workers as they left traditional industries. The partnership retrained thousands of redundant steelworkers into everything from running their own businesses to horse dentistry. Alasdair McDiarmid, Community’s Operations Director, recalls that this approach represented the core of the ISTC’s values—even if members lost their jobs the union would not abandon them.Footnote 13 Match funding from the European Social Fund meant that the costs donated by companies through paid release from work could be doubled, facilitating high quality training. However, despite these positives, closures of traditional industries meant the loss of unionised jobs with strong collective bargaining frameworks. This innovative approach to the union’s learning work was part of the reason for the choice of union name when in 2004 the ISTC merged with The National Union of Knitwear, Footwear and Apparel Trades (KFAT) to create Community, a union which represented people not only in the workplace but also in their communities.

In 2007 Corus group was acquired by Tata who (many believed) overbid for the company in a brutal bidding war with CSN. Tata paid £6.2bn for the company (Bream and Leahy, 2007), valuing it at around 9 times annual earnings. Tata’s shares fell sharply when the news broke, with analysts fearing it would be overextended. Meanwhile, Corus shares boomed as investors expected Tata to deliver cost savings and improved profitability.

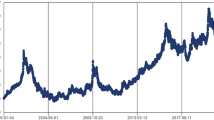

In the wake of the 2007 financial crisis, the steel markets were volatile. While the steel industry had always been cyclical, following 2008 business cycles that had previously been measured in years could change over the course of months.Footnote 14 This steel crisis left the industry in a state of instability that has not fully abated 14 years later. As a result, most steel companies attempted to restructure their businesses. Restructuring programmes with titles like ‘fit for the future’ and ‘weathering the storm’ resulted in extensive job losses.Footnote 15 To their credit, union reps managed to achieve the restructures without any compulsory redundancies. Instead, older members approaching retirement took the opportunity to leave on a voluntary basis.Footnote 16

A defining trend in recent years has been fragmentation, as the industry splintered through sell-offs. Whilst fragmentation was challenged at the time, it was apparent that employers were not willing to invest in plants that they did not see as part of their core businesses or strategic long-term vision. Given the pace of change in the steel industry, plants would quickly have become unprofitable without ongoing investment. For Alasdair McDiarmid (Operations Director, Community Union), divestment may realistically have been the only way for surviving plants to continue to get the investment they needed to be profitable.Footnote 17 In 2011, the fragmentation of Tata Steel UK began with the Redcar plant sold to SSI. The sale was seen as a hopeful step forward, as in 2009 the plant at Teesside had been mothballed. Rescue seemed secure when the plant was bought by the Thai company SSI, and production restarted.

Then in 2015, crisis hit Redcar. The plant’s owner disappeared as the business fell into liquidation and the plant was closed (Arnold 2020). The business model had entailed making steel in the UK and shipping it to Thailand to be rolled. Some commentators argued this was not a sustainable model from the start, but it had worked, for a time, until steel prices fell. Community argued that a rescue could have been attempted by separating the plant in the UK as a standalone and using rolling facilities in the UK. Estimates suggested that for a cost of about £20m the Conservative government could have secured the coke ovens and the furnace.Footnote 18 Instead, tragedy struck the community in Redcar in just the same way it had hit plants like Ravenscraig in the past. Steel unions have long warned that communities are devastated when a key employer is removed from an area.

The SSI crash was devastating, showing that even today communities remain dependent on steel. In Redcar, regional salaries fell dramatically—calculations based on ONS data show that median gross weekly earnings fell from £531 before the closure to £496 afterwards, a reduction from 4% below the national average to 15% below it. Serious harm was done to people’s mental health and there were many cases of family breakdown. The jobs that former steelworkers moved into were predominantly self-employment and service jobs, generally un-unionised, and significantly more insecure than the jobs left (Coats, 2020, pp. 42–46). This tragedy occurred despite significant efforts from the government to support workers in the sector—£80 million was invested in reskilling, retraining and redundancy payments (Coats, 2020, p. 46), and there was a good example of the principles of social partnership that unions like Community have been promoting.

Whilst it is not clear that the government fully learned the lessons from the collapse of the SSI site, there is evidence that it wanted to avoid lightning striking twice. Later, in 2016, the Scunthorpe-based long products business was sold to Greybull (British Steel 2020) and the engineering steels business in South Yorkshire was acquired by Liberty in 2017.Footnote 19 For the unions, this entailed moving into multiple sets of negotiations and industrial relations structures. But, when the same threat appeared in 2019 in Scunthorpe and it seemed the business was heading like Redcar towards liquidation, the government stepped in to provide an indemnity to the official receiver, which meant they were able to keep the business trading whilst a buyer was found. Eventually British Steel was acquired by the Chinese steel company Jingye (British Steel 2020).

Notably, the steel unions argued that the success of this rescue exposed the lie that no government intervention could have been attempted inFootnote 20Redcar. In subsequent years steel companies have continued to look for opportunities to divest assets, and the legacy of 2008 continues. Yet, for all it has faced in the past, the new set of challenges that the steel industry is facing today dwarf any that it has faced before i.e. decarbonisation.

6 Unions and Steel in the Net Zero Future

Community and the other steel unions have never shied away from acknowledging the urgency of the climate crisis (Community Union, 2021). Human-caused emissions are driving global temperatures up. To stop catastrophic global warming and climate change, it is imperative that the global community reduces its carbon emissions. Since its earliest days, the steel industry has been fuelled by carbon rich materials, charcoal in antiquity, coal since. Now dramatic changes in manufacturing methods are needed to make steel in a way which emits far less carbon.

At the same time, to manage the green transition the world will need steel. Steel will be an essential part of the supply chain for everything from electric automotives to wind turbines (Azevedo et al., 2022). Many of the green industries of the future can simply not be delivered without steel. Decarbonisation of the UK domestic steel industry is thus essential not least because of the emissions associated with transporting steel, the only alternative to domestic production. It has been estimated that transport costs alone meant that the carbon emissions associated with importing steel from China were fifty times that of steel produced in the UK (UK Steel, 2021: 6).

Significant investment is required to ensure that the industry reaches its net zero targets. The year 2021 represented a pivotal decision point for the UK government and for the steel industry as a whole. In March 2021 Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Kwasi Kwarteng resurrected the Steel Council, which had fallen into disrepute mainly because of a failure to agree on objectives amongst employers.Footnote 21 The resurrection gave steelworkers hope that the industry’s future would be taken seriously in a year where the UK government’s decision to host the COP26 conference placed its own climate policies in the international spotlight. COP itself also created an opportunity, disappointingly not seized, to set out a meaningful plan for the steel industry.

One of the areas of consensus is the importance of competitive energy prices to the future success of the steel industry.Footnote 22 Unions and industry argue alike that any of the technologies that will replace the existing technologies will require significantly more electricity than blast furnaces. For many years the UK steel industry has suffered a competitive disadvantage on electricity prices, sometimes paying double the price paid by producers in France or Germany.

Furthermore, the steel industry is the backbone of communities. Lessons learnt the hard way from Ravenscraig to Redcar show the tragic human consequences if steel is lost. The energy price surges of 2021−2022 have stretched the finances of both workers and steel companies to the limits, threatening the UK’s Net Zero targets. This is disappointing given that the transition has the potential to create and protect steel jobs. Newer technologies like Hydrogen and DRI (Direct Reduced Iron) steelmaking will require significant investment and strategic thinking about the direction for the UK (Spatari et al 2021). Yet underinvestment has characterised the history of the UK steel industry, so serious change must be made to achieve a result that supports future industrial success as well as protecting good jobs, and communities.

7 Conclusions

Reflecting on the number and variety of challenges UK steel workers have faced over the years, what is remarkable is their great resilience despite continued patterns of underinvestment and failure to protect and support the industry to adapt. As a trade union, we have been proud to put forward workers’ voices throughout that history, ensuring that government and employers recognise their impact on people and communities. Without the constant focus of unions on protecting their members, improvements to conditions in the UK steel industry would not have been achieved and efforts to help communities through industrial change would have been weaker.

As European steel industries continue to face substantial challenges, it’s imperative that a co-ordinated effort is directed towards achieving net zero. Lessons from the past must be learnt to ensure communities are not harmed as the economy transitions—no communities should face the fate of Ravenscraig or Redcar. It is more essential than ever that workers’ voices are heard, throughout this process and that governments, employers, and unions work together as the industry takes on perhaps the greatest challenge it has ever faced.

Notes

- 1.

Pig iron is so named because traditionally the liquid metal was run out into moulds carved into the sand, with a long channel and ingots at right angles to it which resemble a sow nursing her piglets (T. S. Ashton, Iron and Steel in the Industrial Revolution, quoted in Pugh 1951, 7).

- 2.

In Europe—crucible steelmaking was known in India from around the 1st millennium AD (Lang, 2017, p. 862).

- 3.

Worth approximately £18.46 in 2022s money.

- 4.

In return for their membership fees at this time, trade unionists could expect to receive a form of rudimentary social insurance, with the union paying benefits such as sickness and accident benefits.

- 5.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 6.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 7.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 8.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 9.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 10.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 11.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 12.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 13.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 14.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 15.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 16.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 17.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 18.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 19.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August, Oxford.

- 20.

Interview with R. Rickhuss, 11th August. Oxford.

- 21.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August. Oxford.

- 22.

Interview with A. McDiarmid, 20th August’. Oxford.

References

Arnold S (2020) SSI five years on: former Redcar steelworks site ‘now under full local control’. The Northern Echo. https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/business/18786656.ssi-five-years-former-redcar-steelworks-site-now-full-local-control/. Accessed 25 Jan 2022

Azevedo M et al (2022) The raw-materials challenge: how the metals and mining sector will be at the core of enabling the energy transition. https://www.mckinsey.com/. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/metals-and-mining/our-insights/the-raw-materials-challenge-how-the-metals-and-mining-sector-will-be-at-the-core-of-enabling-the-energy-transition?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hdpid=7236476e-7fa1-41ea-84f8-6f923bcde51b&hctk. Accessed 20 Jan 2022

Beebee M (2020) 2019 labour history review essay prize winner: navigating deindustrialization in 1970s Britain: the closure of Bilston steel works and the politics of work, place, and belonging. Labour Hist Rev 85(3):253–284. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/123869/Beebee_Navigating

Bill (2006) Ind Law J 36(4):492–495. https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwm034

Bream R, Leahy J (2007) Tata steel wins corus with £6.2bn offer, financial times. https://www.ft.com/content/e8191bda-b0d9-11db-8a62-0000779e2340. Accessed 22 Dec 2021

Coats D (2020) A just transition? managing the challenges of technology, trade , climate change and COVID-19. https://www.ferryfoundation.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=d3595d49-cb31-40c3-8a28-d6e7a4846866

Evans C (1998) A skilled workforce during the transition to industrial society: forgemen in the British iron trade, 1500–1850. Labour Hist Rev 63(2):143–160

Fabián O (2018) The legend of Benjamin huntsman and the early days of modern steel. MRS Bull 43(8):637–637. https://doi.org/10.1557/mrs.2018.195

HC Deb (22 January 1931) (1931). http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1931/jan/22/trade-disputes-and-trade-unions#column_458. Accessed 11 Feb 2022

Hutton G et al (2021) .UK steel industry: statistics and policy. House of Common Library. (7317). www.parliament.uk/commons-library

Lang J (2017) Roman iron and steel: a review. Mater Manuf Process 32(7–8):857–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2017.1279326

Moss S (2001) Life after steel. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/g2/story/0,3604,438063,00.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2022

Novitz T (2007) ‘The right to strike: from the trade disputes act 1906 to a trade union freedom

Office for National Statistics (2022) Retail prices index: long run series: 1947 to 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/cdko/mm23. Accessed 25 Jan 2022

Peace Treaty of Versailles (1919) League of nations. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/treaty_of_versailles-112018.pdf

Pugh A (1951) Men of steel by one of them. The Irons and Steel Trades Confederation, London

Simpson B (2007) Judicial control of the CAC. Ind Law J 36(3):287–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwm017

Smith T (2018) ‘Remembering Corby’s hot metal past’. Steel Times Int 42(3):76. https://www.proquest.com/openview/744b14356d65802bb4f41128a23af45a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1056347

Spatari M, McDonald C, Portet S (2021) Decarbonisation of the steel industry in the UK: towards a mutualised green solution. www.syndex.org.uk. Accessed 18 March 2021

British Steel (2020) Where we’ve come from. https://britishsteel.co.uk/who-we-are/where-weve-come-from/. Accessed 25 Jan 2022

UK Steel (2021) Maximising value: positive procurement of steel. www.makeuk.org/uksteel.

Stroud D, Fairbrother P (2012) The limits and prospects of union power: addressing mass redundancy in the steel industry. Econ Ind Democr 33(4):649–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X11425542

The National Archives (TNA) PREM19/308 f38 (1980) ‘Record of a meeting held at 10 downing street on monday 21 january 1980 at 10.30 AM to discuss the steel dispute. The National Archives. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/116071

Community Union (2021) Building a greener future. https://community-tu.org/who-we-are/what-we-stand-for/climate-change/

Upham M (1997) Tempered-not quenched. Lawrence and Wishart Limited, London

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mowbray, A. (2024). The History of the Steel Industry: A Trade Union Perspective from the UK. In: Stroud, D., et al. Industry 4.0 and the Road to Sustainable Steelmaking in Europe. Topics in Mining, Metallurgy and Materials Engineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35479-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35479-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-35478-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-35479-3

eBook Packages: Chemistry and Materials ScienceChemistry and Material Science (R0)