Abstract

Recommender systems determine the content that users see and the offers they receive in digital environments. They are necessary tools to structure and master large amounts of information and to provide users with information that is (potentially) relevant to them. In doing so, they influence decision-making. The chapter examines under which circumstances these influences cross a line and can be perceived as manipulative. This is the case if they operate in opaque ways and aim at certain decision-making vulnerabilities that can comprise the autonomous formation of the will. Used in that way, they pose a danger to private autonomy that needs to be met by law. This chapter elaborates where the law of the European Union already adequately addresses these threats and where further regulation is needed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Recommender systems select the content that is being displayed to platform users and thereby shape user’s perception of available content, information, choice and – in a way – of the world. Some platforms consist almost exclusively of recommendations (Seaver 2019). There is a vivid debate about how recommender systems influence equality, societal discourse, polarization and democracy (Milano et al. 2020; Beam 2014; Susser et al. 2019a). Clearly, recommender systems do influence behavior (Calvo et al. 2020). Some concerns have been raised as to the manipulative potential of recommender systems and their negative effects for human autonomy.Footnote 1

This chapter looks at recommender systems from a civil law perspective, more precisely, from the perspective of European Private Law and private autonomy. It explores the question of whether and when recommender systems and their recommendations manipulate recipients’ decision-making in a commercial context. It further examines where the law of the European Union already prohibits such manipulative influences, where relevant regulations are emerging and where there is still a need for regulation.Footnote 2

After giving a brief introduction to the role of private autonomy and private law’s stance towards influence (6.2), the paper maps different recommendation settings relevant to the question asked above (6.3). It goes on to look at different philosophical concepts of manipulation (6.4). The non-legal concepts of manipulation serve to assess different features of recommender systems and under which circumstances recommender systems’ influences should be considered manipulative (6.5). Finally, the paper examines which of the manipulative settings identified in Sect. 6.5 are already subject to regulation and which issues should be further regulated to safeguard the autonomous decision of recommendation recipients (6.6).

2 Autonomy and Influence in Private Law

The term private autonomy describes the right of individuals to shape their legal relationships according to their own will (Flume 1979; BVerfG NJW 1994, 36). The idea of it derives from the image of mankind as naturally free that is the basis for all human rights and freedoms.Footnote 3 Private autonomy is a fundamental principle of European private law.Footnote 4 Within private law, this principle offers the basis for freedom of contract, including freedom of choice and the principle of will or intent (Study Group on a European Civil Code and Research Group on EC Private Law (Arquis Group) 2009: II. – 4:101 DCFR), i.e., that contracts are being formed because of a declared will. Private autonomy requires, on the one hand, that the state leaves citizens in principle free to shape their legal relationships (Busche 1999) and, on the other hand, that the state creates and secures conditions that enable them to exercise their rights (Study Group on a European Civil Code and Research Group on EC Private Law (Arquis Group) 2009). For constellations of obvious power imbalances, in which the stronger party can impose their will on the weaker, leaving no or little room for the weaker to exercise their autonomy, the state must limit one party’s autonomy to protect at least a minimum of autonomy for the other (Möllers 2018; Busche 1999).

Because humans live together in societies and form legal relationships with each other, private autonomy can never exist in absolute terms. It must necessarily be limited in order to guarantee the rights and freedoms of others as well as certain (public) values and principles (e.g., personal responsibility, fairness, legal certainty and others. See Riesenhuber 2003). Social coexistence must therefore be regulated to a certain extent. Being a principle, private autonomy can only be realized to a certain degree (Riesenhuber 2018). The enjoyment of autonomy by one person in comparison to the autonomy of another or with regard to other principles is the result of a balancing exercise and largely a value judgement. The results of these balancing exercises are by no means set in stone.Footnote 5 Each generation must determine which values, policies and principles should be given priority to and, in situations of colliding individual autonomy, whose autonomy to strengthen and whose to limit.Footnote 6 Even though private autonomy is a legal concept, the decisions about its scope and level of legal protection (in the light of other values and legal principles) is mainly a political decision, hence one that may change over time or in the face of technical developments, and is open to extra-legal influences.Footnote 7

An autonomous decision requires also that the decision-making process, the formation of the will, was sufficiently autonomous. European private law assumes that a decision is autonomous when it is informedFootnote 8 and free from certain types of influences (Cf. Study Group on a European Civil Code and Research Group on EC Private Law (Acquis Group) 2009: II. – 7:205 ff. DCFR).

When legal subjects communicate and establish legal relationships with each other, they (in principle legitimately) follow their own interests. They necessarily (try to) influence each other. Whoever wants to sell something needs to present the sales item in a good light. Whoever wants to conclude whatever kind of contract with someone else needs to convince the other to do so (Cf. also Köhler 2021: UWG § 1 Rn. 17). Obviously, not any form of influence on someone else’s decision can count as an interference with the other’s autonomy that is to be prevented or otherwise sanctioned by law. Usually, the following types of influences are considered undue influences: coercion, unlawful threat and deception (or fraud).Footnote 9 Where the conclusion of a contract was induced by such means, the contract can be voided.Footnote 10 European Unfair competition law prohibits commercial conduct that is contrary to the requirements of professional diligence, and is likely to materially distort consumers’ economic behavior,Footnote 11 especially when it is misleading (deceiving)Footnote 12 or aggressive (harassing, coercing, or unduly influencing in a way that is at least likely to significantly impair the average consumer’s freedom of choice or conduct).Footnote 13

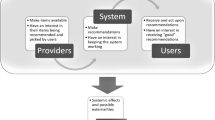

3 Recommender Systems and Their Influence

The EU Digital Services Act (DSA)Footnote 14 defines recommender systems as a “fully or partially automated system used by an online platformFootnote 15 to suggest in its online interface specific information to recipients of the service or prioritise that information, including as a result of a search initiated by the recipient of the service or otherwise determining the relative order or prominence of information displayed.”Footnote 16 While recommender systems normally are programmed to display information or offers that are likely to be of interest for the recipient (a platform user) (Ricci et al. 2012), that does not mean that the predicted interest is necessarily the only reason behind a recommendation (Seaver 2019). Recommender systems exist in different forms and contexts. One can roughlyFootnote 17 distinguish two categories of recommendations: related and unrelated recommendations.

‘Related recommendations’ are recommendations that are related to what the user is currently looking at or looking for. In this category fall recommendations that are being generated in reply to a specific user search query, e.g., the result list on Amazon when a user searches for a smartphone. The recommender system decides which offers are being displayed and in which order (ranking). Then there are recommendations that are related to a current user choice (maybe following a search query). For example, when a user clicks on one of the offered smartphones, the Amazon recommender displays similar items and/or accessories like display protections, earphones or cases. The newsfeeds in a social network made up of posts and shared content by “friends” or dynamic news websites are other examples of related recommendations. Recommender systems decide what content (which news or whose posts) to display, and these decisions sum up to lists of related recommendations: they are based on what the user is looking for when she visits a news page or social network.

‘Unrelated recommendations’ are recommendations that are not related to what the user is currently looking for. Many websites are financed through advertisement and recommender systems can be used to decide which advertisement is displayed to which user (Calo 2014). Those advertisements are usually unrelated recommendations, because the user is not looking for them but for other content on the website. That is the case e.g., of advertisements displayed in a social network’s newsfeed or news websites that users consult to see what content “friends” have posted and shared or to read news. Another form of unrelated recommendations are those being displayed in more or less fixed categories on many homepages of sales platforms. The recommendations may either address every userFootnote 18 or may be personalized for a specific user.Footnote 19 They might be triggered by earlier search queries of the user but are in any case not related to what the user is currently looking for. Unrelated recommendations are often a form of personalized or targeted advertising.

Recommendations can be based on or influenced by many different factors and filtering techniques (Ricci et al. 2012): Content-based recommender systems recommend items that are similar to those that a user has preferred in the past. Other recommender systems base their recommendations on demographic characteristics of the users. In “community-based”-filtering, recommendations are based on the preferences of the user’s “friends”. Collaborative filtering recommends items to the user that other users with similar preferences have liked in the past. These are just examples of common filtering techniques. Often, the different techniques are combined in hybrid models to overcome the weaknesses of some techniques.Footnote 20 Many recommendation techniques, e.g., basing recommendations on prior user behavior or demographic characteristic require some level of profiling.Footnote 21

Recommender systems decide, in any case, which options are being brought to a user’s attention. Recommender systems do not threaten or coerce users into any decisions. They are filtering tools that pick, usually from large pools of contents or offers, what to present to users. They influence the perception of available choices and thereby the users’ choices. Depending on how recommender systems are integrated into platforms, they might steer user attention in a certain direction. Is this manipulative, as some have claimed?

4 Manipulation

To understand what is behind the claims that recommender systems are manipulative and why manipulation is undesirable, it is helpful to take a brief look at the philosophical literature on manipulation. In philosophical discussions, the term “manipulation” is usuallyFootnote 22 used to describe influences that do not respect the autonomy of the influenced person (Susser et al. 2019b; Raz 1988). They are perceived as immoral or unfair precisely because they are thought to disrespect and harm the other’s autonomy (Sunstein 2016; Raz 1988; Susser et al. 2019b).

The value of autonomy is mostly undisputed in the western world (Rössler 2017; Raz 1988). Kant attributed the unconditional value of human dignity to human autonomy.Footnote 23 According to self-determination theory in psychology, autonomy is one of three basic psychological human needs (Ryan and Deci 2017). While the lack of it negatively influences health and wellbeing, autonomy improves human energy and motivation (Ryan and Deci 2017, 2000; Deci and Ryan 2008). Philosophers have understood autonomy as a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for a felicitous life (Rössler 2017; Dworkin 1988; Raz 1988). Individual autonomy is also an essential presupposition of democracy. “It is only because we believe individuals can make meaningfully independent decisions that we value institutions designed to register and reflect them” (Susser et al. 2019a). Autonomy is also recognized as a value from a more utilitarian perspective, and was for instance supported with the argument that economic systems based on self-determination have so far been the most successful systems for increasing general welfare (Lobinger 2007 arguing that because the improvement of one’s own living conditions regularly sought through autonomous action usually only succeeds if the needs of others are also satisfied). Whether it is thought in an instrumental way or not, autonomy is a value and manipulation is problematic because it is incompatible with this value.

From the perspective of autonomy, many acts can count as manipulative (Sunstein 2016). The term “manipulation” describes a targeted influence to control the behavior of others,Footnote 24 the “handling or managing of persons (Harper 2022).” In that sense, coercing someone to do something, for instance, would be an act of manipulation. However, in the philosophical debate, and often in ordinary language, the word manipulation is usually used to describe a more distinctive type of influence that is neither coercive nor persuasive (Noggle 2020; Faden and Beauchamp 1986). There is a considerable number of attempts in the literature to find a unitary concept of manipulation.Footnote 25 As I am not concerned with regulating manipulation in general, but only with assessing whether certain features of recommender systems can count as manipulative, I don’t need a conclusive definition of manipulation. It is sufficient to identify typical features of manipulative influences and criteria to distinguish unwelcome manipulative from benign i.e., non-manipulative influences.

Manipulative influences are often described as attempts of subverting rational deliberation or the capacity for conscious decision making, bypassing deliberation altogether or introducing non-rational influences in the deliberation process (Susser et al. 2019b; Noggle 2020; Faden and Beauchamp 1986). Raz claims that manipulation “perverts the way [a] person reaches decisions, forms preferences, or adopts goals” (Raz 1988). Drawing on the heuristic concept of the two systems of the mind (Kahneman 2011), in which system 1 is considered to be an “automatic, intuitive system, prone to biases and to the use of heuristics, while System 2 is more deliberative, calculative, and reflective”, Sunstein says that manipulators usually address system 1 and try to bypass system 2 (Sunstein 2016). Susser/Rössler/Nissenbaum speak of targeting and exploiting decision-making vulnerabilities (Susser et al. 2019a; cf. also Spencer 2020).

Only the introduction of non-rational influence cannot be sufficient to label an influence as manipulative. Many non-rational influences seem to be perfectly acceptable with a view to autonomy and are commonly considered benign (e.g., using perfume and dressing up for a date) (Noggle 2020; Sunstein 2016). Sunstein therefore suggests that an effort to influence someone’s choice should only count as manipulative when “it does not sufficiently engage or appeal to their capacity for reflection and deliberation” (emphasis added) (Sunstein 2016). This sufficiency criterion is context sensitive and allows one to take a number of other factors into account that seem to be relevant when judging whether an act or conduct is manipulative, e.g., the particularities of the context, the role of the influencer and the relationship with the influenced (cf. Sunstein 2016).Footnote 26

Another attempt to distinguish between manipulative and non-manipulative influences builds on the idea that manipulators intend to make others fall short of ideal behavior. According to Noggle, the common feature of manipulative acts is that they try to lead the victim astray (Noggle 1996). He claims, there are certain ideals to which we strive for when we form our beliefs, develop emotions and desires – such as the ideal that one should believe what is true, or focus on what is relevant and have emotions that are appropriate to given situations (Noggle 1996). Noggle observes that “[m]anipulative action is the attempt to get someone’s beliefs, desires, or emotions to violate these norms, to fall short of these ideals” (Noggle 1996). In his view, the ideal setting is not to be determined by “what the influencer thinks are the ideal settings for the person being influenced” (Noggle 1996). Drawing on Noggle’s concept, Barnhill suggests that manipulation is “directly influencing someone’s beliefs, desires, or emotions such that she falls short of ideals for belief, desire, or emotion in ways typically not in her self-interest or likely not in her self-interest in the present context” (Barnhill 2014). In this account, what is crucial is not what the influencer thinks about the ideal settings for the influenced person, but whether his act or conduct would typically benefit or not the self-interest of the influenced (Susser et al. 2019b). This is a more objective and verifiable criterion.

Faden/Beauchamp suggest that an influence is manipulative when the influence is either difficult to resist or when it attempts to cause the influenced to fail to substantially understand his action, the circumstances or the consequences (Faden and Beauchamp 1986). They analyze, amongst others, cases of manipulation through offering. This is particularly interesting in our context because recommender systems display offers. Faden/Beauchamp suggest that, as a rule, a welcome offer made while the influencee “is not simultaneously under some different and controlling influence causing acceptance or rejection of the offer” is compatible with the autonomy of the influenced (Faden and Beauchamp 1986). An unwelcome offer is compatible with autonomy “if it can be reasonably easily resisted” (Faden and Beauchamp 1986). They judge offered “mere goods” to be usually easy to resist and “generally more compatible with autonomous action than […] harm-alleviating goods” (Faden and Beauchamp 1986).

Manipulation is typically (but not necessarily (Sunstein 2016; Barnhill 2014; Klenk 2021)) covert,Footnote 27 in the sense that the target of manipulation “is not conscious of the manipulator’s strategyFootnote 28 while they are deploying it” and “couldn’t easily become aware of were they to try and understand what was impacting their decision-making process” (Susser et al. 2019a). In many accounts, deception – i.e., covertly influencing the decision-making process by causing false beliefs in the victim – is one case of manipulation (Susser et al. 2019a, b; Faden and Beauchamp 1986; Noggle 1996, 2020).

Despite the (smaller or bigger) differences in the various conceptualizations of manipulation, there is general agreement in some regards: Manipulation can have many different formsFootnote 29 and can address different levers: someone’s beliefs, desires, emotions, habits, or behaviors (Susser et al. 2019a, b).Footnote 30 Manipulative influence (i.e., influence that does not respect the other’s autonomy) is a controlling kind of influence (Faden and Beauchamp 1986; Noggle 1996);Footnote 31 manipulators treat people as “puppets on a string” (Wilkinson 2013; Sunstein 2016; Susser et al. 2019b).Footnote 32 Sunstein says: “[t]he problem of manipulation arises when choosers justly complain that because of the action of a manipulator, they have not, in a sense, had a fair chance to make a decision on their own” – that is, if due to the influence the decision was made without sufficiently assessing costs and benefits on the choosers’ own terms (Sunstein 2016). For an act to count as manipulative it requires the intention to manipulate (Susser et al. 2019a; Spencer 2020; Noggle 1996; Faden and Beauchamp 1986).

Where the influence fails and the influencer does not achieve his goal one cannot say that someone has been manipulated, but the influencing act itself can still count as manipulative.Footnote 33 Even an unsuccessful act of attempted manipulative influence disrespects the other’s autonomy. Considering this, it is convincing to say that an influence can be manipulative even when the influenced person would not have acted differently without the influence (Susser et al. 2019b; Calo 2014).

There remains one last question that needs to be answered here: Is manipulation always wrong? What if the manipulated person turns out to be very happy with the result of her manipulated choice? In Barnhill’s account, an act would not count as manipulative when the influence aims at the best interest of the influenced (Barnhill 2014). This is not convincing from the perspective of autonomy (Sunstein 2016). Autonomy includes the freedom to make unreasonable decisions and to act in ways that are not in one’s best interest (Raz 2009; Scanlon 1986).

But to be straightforward: Manipulation is not always wrong; it can be justified (Susser et al. 2019b). From a welfarist point of view, manipulation could be accepted if it makes the life of the manipulated or others better (for instance, Sunstein (2016) examines the welfarist perspective, pro and cons towards manipulation). There may be a convincing argument for this if the subject of the discussion is manipulation by the state’s democratically legitimized organs acting in the public’s interest (Thaler and Sunstein 2008) or maybe by parents who have a special duty to care for their children and to act in their best interest. However, if the question is about manipulation in impersonalFootnote 34 civil relations, this argument is questionable. In this realm, no one has a right to manipulate the other’s decision, though one can try to influence it in many ways. It is also hard to imagine that in this context manipulation happens for the mere good of the manipulated person,Footnote 35 even though the person might be happy with her decision (either because the result is good for her or because she never learned about better options). Private autonomy is limited by the rights of others but not by other’s opinions on what is good or in someone’s interest.

5 Recommender Systems and Manipulation

5.1 Recommendations in General

Recommending something is always an attempt to take influence, but not necessarily an attempt to manipulate and to disrespect the other’s autonomy. Filtering and ranking information is inevitable. Platform algorithms need to make a choice on what to display and in which order. Even if the filtering was not automatized, someone would need to fulfil this task in one way or another. Almost everything that we see in the world around us is based on a choice (hence a filtering) someone made. The shop owner needs to decide which goods to sell and where to place them, whether to highlight them etc. These decisions determine our options and how we perceive them. The mere fact that platforms use algorithms to fulfil the necessary task of deciding which options to present and which to highlight does not render the influence manipulative, even when some knowledge on the user plays a role in determining the recommender’s choice.

As a principle and result of private autonomy, platform owners are free in what they offer and what they highlight. If it is a commercial platform, it is obvious to users that commercial interests determine the platforms’ choices. The commercial interests do not need to clash with the user’s interests. When, for example, a platform’s recommender system manages to recommend relevant items to the user who consults the platform with the intention to conclude a contract of whatever kind, that benefits everyone. Recommendations can hardly be considered per se manipulative from the perspective of private autonomy. There are, however, certain aspects to consider.

A recommendation is in many situations understood as “a suggestion or proposal as to the best course of action.”Footnote 36 It follows that the addressee usually has certain expectations about the recommended something (action, good, service …), e.g., that it is of special quality, has a good price or is of interest (Peifer 2021). One asks for recommendations when one is looking for something that fulfils one’s needs or that one is likely to enjoy. One expects the recommender to base the recommendation on the knowledge of the recommended item and its specific features. In some cases, one might also expect the recommender to consider the specific needs of the addressee or his or her taste.

A search query on a platform is in a sense asking for recommendations. When users search for something on a platform and receive a list of results, they would usually have the expectation that the ranking is determined by some kind of quality criteria and that the results displayed at the top of the list are there because they are particularly relevant to the search and/or of a particular good quality (e.g., price-performance ratio). However, the platform providers may have all kinds of reasons to display and recommend certain products and program their recommender systems accordingly. They might for example have a special interest in selling some products more than others, might have received money in return for a better ranking or might display items that are overpriced to make the user accept the average price easily, or the like.

If recommendations are opaquely dominated by other factors than those that a user would reasonably expect in a given situation, it can be considered misleading or manipulative. Ranking an item high up in the search results induces the belief that it would be good for the user to choose this item because it was ranked well. That applies even though users are generally aware that the platform operator is pursuing commercial purposes, because that usually does not foreclose that an offeror acts also in the interest of her customers. If the decisive motive to rank the item high is a different one, the user is being induced to form a wrong belief and is led to make a decision that may not be in her best interest.Footnote 37 The user is being deceived and manipulated, because they are led to base their decision on a wrong assumption. They are being led astray, to speak with Noggle’s words, from the ideal to base a decision on true facts. If the unexpected recommendation-criteria are made transparent to the user, there is usuallyFootnote 38 no problem.

Pointing a user to other items that are somehow related to the one they were just looking at, does not raise concerns. Drawing a user’s attention to other similar items so they can compare and make the best choice for them or to look at other items that could be additionally useful cannot be considered as leading them astray, because first, the additionally given information is not irrelevant nor is it typically against their interest to look at further items. It may even be autonomy-enhancing. Apart from this, additional offers are usually easy to resist, and there is nothing irrational or covert about the influence.

5.2 Labelled Recommendations

In many cases, transparency regarding recommendation criteria will foreclose manipulation. But can the explicit reference to a recommendation criterion not be itself manipulative?

Often, recommendations (related or not) are based on experiences with other customers (Ricci et al. 2012). Some platforms label popular items as “bestseller” or headline a recommendation category as “popular on [platform name]”, “other customers also bought” or alike. The labelling draws attention to what other people do. One can suspect that this draws on the bandwagon effect, the human tendency to follow the crowd (Thaler and Sunstein 2008). Can this practice be considered manipulative?

Even though the impulse to follow the crowd may not be purely rational, it is also not fully irrational. Of course, the bandwagon effect may reinforce the success of already successful products. However, the fact that others have opted for something is at least an indication that a product may be good or useful (in some way), if some of the buyers have informed themselves about the product, were happy with it and recommended it privately.Footnote 39 Bestseller lists are long established, especially in the music and book trade. If the information is true (i.e., that an item is a bestseller or that other people, who bought the item the user is currently looking at, also bought a certain accessory), providing it is neither deceiving nor manipulative in some other way. Even though the information is also addressing the less reflective system of thinking (system 1), the capacity for reflection and deliberation (system 2) is still sufficiently engaged, especially considering that it is a longstanding and accepted practice. Merely informing (in a non-deceptive way) about a fact can usually not be considered manipulative, even if people tend to react to the information given in a certain way (expected and desired by the influencer) (cf. Sunstein 2016).Footnote 40

5.3 Unrelated Recommendations

5.3.1 In General

Unrelated recommendations address the user at a time when she is not looking for something, or rather, when she is looking for something else. They can divert the user’s attention away from what she was originally interested in. Are they manipulative?

Noggle and Barnhill would probably consider unrelated recommendations (and maybe most advertisement) as manipulative, because when a user is reading a news page or scrolling through his social media feed, the ideal for these situations would be to focus on the primary information sought and (ad-)recommendations that are placed in other contexts are intended to capture the attention and draw it away from the primary information.

However, unrelated recommendations are usually non-controlling. An advertisement that is not related to the context in which it is placed is socially accepted and, apart from its direct ends, serves the objective of financing services. This is not a new or special phenomenon in the online environment. Though most advertisements do not only address rational capacities for deliberation, it usually still sufficiently engages reflection. If one accepts Sunstein’s sufficiency criterion, one must be open to acknowledge that the addressee’s awareness of the role and purpose of the influencer matters. Seeing an advertisement that is recognizable as such, the viewer usually knows its motives and purposes. Unrelated recommendations are – welcome or not – offers that are generally easy to resist.Footnote 41 Internet users are accustomed to this practice and the brain is usually capable of filtering out information that it does not consider relevant in a given situation (Mik 2016) and that does not capture the attention due to special circumstances.Footnote 42 Of course, these kinds of recommendations may still leave a subconscious trace. Though this is a calculated effect, it is socially accepted and unrelated recommendations are not per se manipulative.

5.3.2 Targeted Recommendations

5.3.2.1 In General

Targeted unrelated recommendations are based on an analysis of the user’s data. The aim is to target a user with advertisements or offers that are likely to be of interest to her in order to increase the chance that she is going to react to it.

Targeted recommendations are likely to be harder to resist than a random advertisement. If the recommender system manages to display something to the user that really is of interest to her, she will feel more tempted to click on the add.Footnote 43 However, as I have said above, as a matter of principle the platform owner is free to display and offer what she chooses to, and the fact that the user is indeed interested in what is displayed to her does not render the recommendation’s influence controlling. Targeted advertisements do not generally engage rational deliberation less than other forms of advertisements and commercial speech.

The question under which conditions personal data may be used for targeted recommendations is a matter of data protection law. As a rule, data processing for this purpose is allowed if the user has consented to it.Footnote 44 In this case there is usually also no problem with a view to private autonomy, because the user has agreed to this kind of influence.

Targeted unrelated recommendations cannot in general be considered manipulative. They can, however, be manipulative under special circumstances. I suggest that this is the case either when they exploit vulnerable moments or when they are likely to play on certain fears of the influenced subject and present allegedly harm-alleviating offers.

5.3.2.2 Exploiting Emotions

It has been reported that platform algorithms can detect users’ feelings and emotions (e.g. insecurity, anxiety, stress, inattentiveness) in real time, based on the analysis of users’ posts, behavior, tone of voice or by measuring mouse or eye movement (Miotto Lopes and Chen 2021; Susser et al. 2019b; Calo 2014).Footnote 45 The information about a user’s current emotional state could be used to exploit vulnerabilities caused by it, to recommend items that the user might be more receptive to in her emotional state. A platform could for example show anti-stress items (meditation apps, anti-stress balls, books on time management etc.) to a stressed user or (overpriced) cosmetic items to insecure teenage girls.

Such practices would specifically target vulnerable situations in which the user is more likely to make less rational and more emotional decisions.Footnote 46 One can argue that, under these circumstances, the rational capacities for decision-making are not sufficiently engaged but rather attempted to be bypassed. Users are more likely to be lead astray from the ideal to first reflect before deciding. Of course, the success of such a strategy depends on the individual users. Some might impulsively buy books on stress management that they will never find the time to read (or they will read it and find it quite helpful) while others will still ignore the advertisement or notice it and decide to calmly research the possibilities of stress management later. Using emotion as a decisive criterion to target advertisement hints to the intention to manipulate, i.e., to exploit a vulnerable situation to provoke a decision in the advertiser’s favor. Exploiting emotions to target recommendations is manipulative especially when the situation is used to incentivize a decision that is likely not in the objective interest of the influenced, because she does not really need it or because she is offered something at a higher price.

Would the influence be of a different nature if the user was informed that the recommendation was based on her feelings? That depends on how much of the influence strategy would be revealed. Telling the user “we recommend this mascara to you because you feel insecure” or “we recommend the meditation app because you are stressed” would no doubt make her aware of the connection between the recommendation and her feeling, but would it help to overcome the decision-making vulnerability? Does that knowledge make her less vulnerable?Footnote 47 In my view, this would not be enough to foreclose manipulation in the case of emotion-based recommendations, because it does not uncover the manipulative mechanism. That would be different if the user was told e.g., “we show this mascara to you because we know that you are insecure about your appearance and we assume that this emotional state makes you more likely to spontaneously buy the mascara and accept the price we set”; or “we suggest the meditation app to you because you are stressed and in this moment probably so desperate for relief that you are willing to conclude a contract for 25 € per month.” It seems unlikely that a platform provider would want to fully disclose this underlying mechanism. Indeed, it is more likely that they would want to keep this strategy secret. This is a further hint of the manipulative nature on such strategies.

5.3.2.3 Addressing Fears Through (Allegedly) Harm-Alleviating Offers

Where the platform holds detailed profiles on their users, the data probably shows when a user suffers from or is under certain conditions (e.g., health issues, financial problems (Susser et al. 2019a)). When this knowledge is used to target recommendations with commercial offers on health products or credit-schemes in a context and at a time where the user is looking for something else, for example reading news, this seems problematic. By seeing recommendations on such products while looking for something else, the user is reminded of her condition in a situation where she intended to focus on something else (cf. Noggle 1996). Because the recommendation touches upon a sensitive issue, it is less likely that she can ignore it or that the brain subconsciously filters it out. To be confronted with one’s problems in an unexpected situation is likely to cause anxiety or other negative feelings, which may cause decision-making vulnerabilities.

When someone decides to inform herself on products related to her problems or health conditions, then she arms herself beforehand, and is prepared to deal with the issue. If confronted with the issue by surprise, that is probably less the case, which seems to make her more vulnerable for less rational decisions. Advertisements for credits and drugs – to stay with my examples – can be perceived as harm-alleviating offers, and it is generally harder to resist to them (Faden and Beauchamp 1986). Targeted harm-alleviating unrelated recommendations should be considered manipulative for the same reasons I have put forward regarding emotion-based recommendations.

5.4 Interim Conclusion: Recommender Systems, Manipulation and Private Autonomy

Recommender systems are not per se manipulative, but they can be used and programmed in a manipulative way. This is the case when recommendations are opaquely based on unexpected criteria or contradict the nature of a recommendation. Recommender systems also work in a manipulative way when they are programmed to use profiling to address fears and target commercialFootnote 48 (allegedly) harm-alleviating offers to users when they are not looking for it. It is further the case when recommender systems are programmed to base recommendations on real time emotion recognition to exploit decision-making vulnerabilities evoked by the emotional state.

This last statement, however, must be qualified. A problem with private autonomy does not arise when the user’s decision does not include any commitment and does not have any legal consequences. For example, the decisions within abo models such as Netflix or Spotify about which song to hear or which movie to watch is in no way binding and unconditionally revocable without any effort. If recommender systems on these platforms would base recommendations on users’ current emotions, this would not impact the formation of a legal relationship.Footnote 49 This is different when it comes to the formation of a binding legal contract. Though contracts concluded online can in many cases be revoked, this comes with further obligations and is conditioned.Footnote 50

It is difficult – if not impossible – to assess which impact recommender systems have, how many decisions they influence that otherwise would not have been taken in that way and what is the economic harm for users that results from such decisions. However, when they are programmed to exert manipulative influences, they pose a danger to the recipients’ autonomy that should be controlled (Calo 2014). The named cases in which recommender systems could interfere with the autonomous decision of users to form legal relationships should be regulated.

6 Regulation Regarding Recommender Systems

For a long time, recommender systems were not subject to explicit regulation. However, this does not mean that no rules applied to them. The deployment of recommender systems and the presentation of the recommendations by online platforms is part of their commercial communication to which all relevant civil law rules concerning commercial communication apply. The processing of personal data for the purpose of making recommendations must of course comply with data protection laws.

However, in recent years, recommender systems have increasingly come to the attention of European legislation. Several legislative instruments have been adopted or are on their way to be adopted that either directly or indirectly regulate recommender systems and targeted advertising. This part examines whether the existing and upcoming legal instruments in EU law are suited to foreclose the manipulative potential of recommender systems identified above.

6.1 Unexpected Recommendation Criteria

The EU Unfair Commercial Practices DirectiveFootnote 51 (UCP-D) prohibits unfair commercial practices, in particular misleading and aggressive commercial practices (article 5 UCP-D). From this general prohibition, it follows that statements accompanying recommendations must be true.Footnote 52 The information that a recommendation is based on other criteria than those to be expected for a recommendation is material for an informed decision and must be made transparent. Not making unexpected recommendation criteria transparent constitutes a misleading omission in the sense of article 7 (1) UCP-D (Peifer 2021).

A recently adoptedFootnote 53 new paragraph 4a of article 7 UCP-D makes this explicit: when platformsFootnote 54 provide consumers with the possibility to search for products and services offered by someone other than the platform itself, information “on the main parameters determining the ranking of products presented to the consumer as a result of the search query and the relative importance of those parameters, as opposed to other parameters shall be regarded as material”.Footnote 55 A new article 6a (1) lit. a in the Consumer Rights DirectiveFootnote 56 (CR-D) contains a correlating precontractual information obligation.Footnote 57 Furthermore, the provision of “search results in response to a consumer’s online search query without clearly disclosing any paid advertisement or payment specifically for achieving higher ranking of products within the search results” has been added to the UCP-D’s blacklist of unfair commercial practises (Annex No. 11a UCP-D).

These rules solve the problem of unexpected recommendation criteria for search result lists on platforms,Footnote 58 however, only in relation to consumers.Footnote 59 This gap is filled by the Digital Services Act (DSA)Footnote 60 that contains explicit rules for recommender systems and the application is not limited to consumer-to-business-relationships.

Article 27 (1) DSA requires providers of online platforms to explain in their terms and conditions the main parameters used in their recommender systems “as well as any options for the recipients of the service to modify or influence those main parameters.” Where several recommendation options are available,Footnote 61 platforms shall make it easy for recipients to choose and modify at any time the relevant recommendation settings.Footnote 62 Art. 38 DSA extends these obligations to very large search engines. It is unfortunate that the DSA only enforces the disclosure of the criteria in the terms and conditions and not more directly connected with the user interface visible with the recommendations.

The DSA further contains a transparency obligation for search unrelated advertisementFootnote 63 recommendations: article 26 (1) lit. d provides that platforms that display advertisement shall provide real-time information for each specific advertisement “about the main parameters used to determine the recipient to whom the advertisement presented and, where applicable, about how to change those parameters”. The information shall be “directly and easily accessible from the advertisement”.

6.2 Targeted Recommendations Exploiting Emotions or Addressing Fears

EU law does not prohibit personalized and targeted advertising. In the political discussion surrounding the DSA, it was debated whether the DSA should generally prohibit targeted advertising, however a full ban was not adopted.

Some limitation to targeted recommendations that exploit emotions or address personal fears or problems of the user derives from the General Data Protection RegulationFootnote 64 (GDPR). Article 9 (1) GDPR prohibits the processing of certain sensitive personal data, amongst others health data and “biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person”. Real time emotion recognition to be used for recommendations would either require the analysis of content the user has just posted or an analysis of specific movements or bodily functions. When detecting the latter (e.g. eye or mouse movement, tone of voice), biometric dataFootnote 65 can be collected in the process. (The voice for example is considered biometric data, Schild 2021). If this is not the case, because for example mouse movement does not allow to identify a person and the movement data is not set in connection with other personal data but used in an anonymized way, the GDPR does not apply.Footnote 66 It is conceivable that for displaying a recommendation based on emotions, the algorithm does not need to know who the user is and does not necessarily need to connect the finding on an emotion (e.g. that a user is stressed) with other data. The mere information about the emotional state could be sufficient information to target advertisement for stress remedies to that user.

The prohibition to process sensitive data does not apply when the person concerned explicitly consented to the processing for the specific purpose. The consent can be requested for several purposes at the same time (art. 9 (2) lit. a GDPR). As a result, the information about the processing purposes often results in long texts that have led to the well-known phenomenon that most internet users (almost necessarily, due to information overload)Footnote 67 click a consent button without reading and reflecting about what they are consenting to (cf. e.g., Ben-Shahar and Schneider 2014). The prohibition to process sensitive data furtherFootnote 68 does not apply to data which the data subject has made public (art. 9 (2) lit. e GDPR). When, for instance, a user publicly posts information about her disease or disability, a platform could use this information to target advertising for medication or other health products.

Article 9 (1) GDPR contains a conclusive list of what is considered sensitive data. Financial information or information on payment behavior is not included. Though the processing of non-sensitive personal data is not unconditionally lawful, it is less restricted. Apart from consent, art. 6 (1) lit. b GDRP offers a broad legal basis for the processing, that is, if it “is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is party or in order to take steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract”.Footnote 69

It can be concluded that the GDPR gives users the possibility to mostly prevent personalized and targeted recommendations by denying consent. In practice, however, this appears to be of limited effectiveness.Footnote 70 Whether, and to what extent, emotion-based recommendations can be prevented by data protection law is questionable (Miotto Lopes and Chen 2022).

One could consider whether targeted unrelated recommendations that exploit emotions or unfortunate personal circumstances for harm-alleviating offers could count as prohibited aggressive commercial practices (article 5 (1), (4) lit. b, 8 UCP-D). A commercial practice is aggressive inter alia if it takes undue influence that is at least likely “to significantly impair the average consumer’s freedom of choice or conduct with regard to the product and thereby causes him or is likely to cause him to take a transactional decision that he would not have taken otherwise” (article 8 UCP-D). In determining whether an influence is undue, several factors shall be considered, amongst others the timing (article 9 lit a UCP-D) and the exploitation “of any specific misfortune or circumstance of such gravity as to impair the consumer’s judgement, of which the trader is aware” (article 9 lit. c UCP-D). At first glance, this could stand in the way of exploiting emotions or personal hardships to target commercial offers. However, moods or emotions themselves are not specific circumstancesFootnote 71 of severe gravity, comparable to a misfortune and the platform is unlikely to know what circumstances caused the mood. Recommendations based on real time emotion recognition therefore cannot be considered an aggressive commercial practice. But articles 5 (1), (4) lit. b, 8 UCP-D also does not foreclose recommendations that address fears for harm-alleviating offers. Article 2 lit. j UCP-D defines undue influence as “exploiting a position of power in relation to the consumer so as to apply pressure […], in a way which significantly limits the consumer’s ability to make an informed decision”Footnote 72 (emphasis added). Simply displaying a certain product depending on the user’s mood or problems does not create pressure (Ebers 2018; Miotto Lopes and Chen 2022).Footnote 73

The DSA does not fully foreclose targeted advertising and recommendations based on emotion recognition or personal hardship. However, it establishes some restrictions beyond the information requirements on the targeting criteria as provided for by articles 27 DSA that alone do not eliminate the manipulative potential of recommendations based on emotions and addressing personal hardships or fears (Miotto Lopes and Chen 2022).

Minors may no longer be targeted with advertisement based on profiling, article 28 (2) DSA. Article 26 (3) DSA prohibits online platforms the targeting of advertisement based on profiling as defined in Article 4, point (4) GDPR using sensitive data (article 9 (1) GDPR). While the parliament’s proposal of the DSA foresaw a general prohibition for targeting and amplification techniques using sensitive data,Footnote 74 the final DSA version contains the insertion that sensitive data must not be used as input data for profiling for targeted advertisement. With this limitation Article 26 (3) DSA is hardly effective against recommendations exploiting emotions or addressing fears, because it does not prohibit targeting information based on sensitive data that was inferred from other non-sensitive data.Footnote 75 Large platforms often have enough user data to be able to draw conclusions, for example, about a user’s state of health or sexual orientation. They can draw conclusions from search queries and purchased products. The DSA’s rules hence do not put a full stop to targeted commercial recommendations based on health data. Emotion-based advertisement targeting is only prohibited as far as it requires the processing of biometric data for profiling.

Article 38 DSA requires at least providers of very large platforms and very large search engines as defined in article 33 DSA to give users the opportunity to choose a recommendation option that is not at all based on profiling in the sense of article 4 (4) GDPR. Platforms that have not been designated as very large do not have to meet this requirement.

The use of emotion recognition systemsFootnote 76 is addressed in the proposed Artificial Intelligence Act (D-AI Act).Footnote 77 A prohibition of emotion recognition for commercial or advertising purposes is not envisioned in the draft.Footnote 78 Emotion recognition operating on commercial platforms is also not considered a high-risk system.Footnote 79 Insofar, article 52 (2) s. 1 D-AI Act only provides for an information obligation: “[u]sers of an emotion recognition system or a biometric categorisation system shall inform of the operation of the system the natural persons exposed thereto.” This provision is intended to protect a person’s informed choice and recognizes the manipulative potential of emotion recognition systems.Footnote 80 But as said above, the mere information is not sufficient to foreclose manipulation in the here assessed cases.

6.3 Regulative Measures to Take Regarding Recommender Systems

The existing European legal instruments do not sufficiently foreclose manipulation through recommender systems to protect platform users’ private autonomy. European legislators should close the identified protection gaps. Not only users of very large platforms should mandatorily be given a choice against profiling-based recommendations. The principal information on recommendation criteria should not just be accessible through links to the terms and conditions but should be given in short right next to the recommendations or in catchwords with the recommendation, as it is required by article 26 DSA only for search unrelated advertisement recommendations. Further and more detailed information can and should be made accessible through links.

There should be clear rules that prohibit targeted recommendations based on real time emotion recognition that apply for all platforms. The exploitation of emotions with the intention to influence legally relevant decision making in a commercial context is highly manipulative. Even if a user would consent to the use of emotion recognition when registering on the platform this does not seem to be sufficient to maintain autonomy in the situation of influence.

Profiling-based harm-alleviating commercial recommendations also in the form of targeted advertising should be prohibited at least as a default setting, even if a user consented to the use of his personal data for advertisement purposes when registering on a platform. Only when a user explicitly opts-in to receiving harm-alleviating recommendations based on profiling the user’s autonomy is sufficiently preserved.

These regulatory measures would not unduly restrict the autonomy of the platforms. In principle, they would remain free to decide on their offerings, but they would not be allowed to influence user decisions in the ways described.

The existing contract law is not suitable to sufficiently compensate for the identified autonomy risks for users. A closed contract can only be avoided if a user can prove deception.Footnote 81 Deception could only be alleged against opaque unexpected ranking criteria, not against the other potential manipulative influences revealed in this paper, and only when the contractor is responsible for the deception. It is questionable whether the platform that uses the recommender system to recommend third party offers is acting as a representative of the contractual partner and whether a user could show that he would have acted differently without the given influence (Mik 2016). Apart from this, the user is likely to never learn that she has been manipulated.

For this reason, also the withdrawal rights provided by EU law for consumer contracts concluded on the Internet are not sufficient compensation. The withdrawal rights are limited in time and the consumer may incur return shipping costs.Footnote 82

7 Conclusion

Recommender systems are useful tools without which it would be impossible to cope with the flood of information available online. They influence decision-making because they decide about what comes to a user’s attention. In many settings, they facilitate choice. They can, however, be used in manipulative ways and be programmed to manipulate. This paper has shown that this is the case when unexpected recommendation criteria are not made transparent and where recommendations aim at certain decision-making vulnerabilities.Footnote 83 This should be prohibited by law. Especially in the amended Unfair Commercial Practices directive, the amended Consumer Rights directive and the Digital Services Act, the European legislator has already taken steps to regulate recommender systems, but there is a need for further legislative action.

Private platforms enjoy private autonomy, just like private platform users. It follows that platforms are in principle free to design their offers and services. If there are no additional circumstances (such as a dominant or significant market position),Footnote 84 they are basically free to decide what they present and offer to whom and on what terms. However, if platform operators try to manipulate legally relevant decisions of their users, it is appropriate to set limits to their freedom to protect the private autonomy of users. Even if the harm to autonomy in the individual case or decision might be small, the systematization and potential scale of this kind of manipulation are worrisome (Calo 2014). Principiis obsta (Susser et al. 2019b)!

Notes

- 1.

E.g. quite boldly: “Evidently, recommender systems deprive human users of liberty due to their controlling influences, and also often agency since human users do not usually provide informed consent when using recommender systems (users often lack the choice and are given a ‘take it or leave it’ option when accessing online services” (Varshney 2020); Calvo et al. have examined the potential influences of a recommender systems on human autonomy in spheres (levels) of life (Calvo et al. 2020; Ebers 2018; Mik 2016; Susser et al. 2019b).

- 2.

There is a more general debate on whether recommender systems decrease (e.g. because they cause humans to make less variant and diverse choices) or enhance overall human autonomy (e.g. by facilitating quick decision-making and saving time that can be used in a self-determined way), see for example Calvo et al. 2020. Albeit central, this question goes beyond the scope of this paper. The paper also does not examine legal problems concerning the relationship between platforms deploying recommender systems and those being recommended (either themselves, e.g. as employers on recruitment platforms or as potential partners on dating sites, or their products and services). These issues are being addressed by Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services (P2B Regulation). The paper is also not concerned with data protection issues regarding the collection of personal data.

- 3.

- 4.

This is true even if the conceptions and dogmatic justifications may be disputed in detail or vary in the different countries. In the DCFR, it is conceptualised as an underlying principle of European Private law, “Party autonomy” (Study Group on a European Civil Code and Research Group on EC Private Law (Acquis Group) 2009).

- 5.

Constitutions and fundamental rights do set certain limits but leave a wide margin for discretion.

- 6.

Cf. Bumke 2017: Autonomy in law must be rethought again and again.

- 7.

- 8.

Real autonomous decisions require that the decision-maker knows what she is doing and that she can (to a certain degree) foresee the consequences of a wilful action or declaration: cf. e.g. Annex I Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market, No. 7; see also CJEU joined cases C-54/17 and C-55/17: Judgment of the Court (Second Chamber) of 13 September 2018, AGCM v Wind Tre SpA and Vodafone Italia SpA, para 45. There is a broad consensus today that knowledge is a prerequisite for autonomous decision-making (Bumke 2017). To enable informed decision making, European Private Law establishes numerous information obligations for situations in which one party typically has superior knowledge than a potential contractual partner.

- 9.

Including fraudulent non-disclosure of relevant information, II – 7:205 DCFR.

- 10.

E.g. § 123 BGB (D) and articles 1130, 1131 Code civil (FR); cf. also II. – 7:205 DCFR. II. – 7:206 DCFR.

- 11.

Article 5 (1) + (2) Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market and amending Council Directive 84/450/EEC, Directives 97/7/EC, 98/27/EC, and 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, here: UCP-D).

- 12.

Article 6 and 7 UCP-D.

- 13.

Article 8 and 8 UCP-D.

- 14.

Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market For Digital Services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act), OJ L 277/1.

- 15.

The use by an online platform, however, is not really a defining criterion for a recommender system. This becomes obvious by article 38 DSA, which applies also to very large search engines. The mentioning of platforms in the definition of article 3 lit. s DSA can be explained with the fact, that the DSA originally should only be applied to platforms. The application was later extended to very large search engines. The fact that platforms continue to be mentioned in the definition of recommender systems is likely due to an omitted editorial correction.

- 16.

Article 3 lit. s DSA.

- 17.

In some cases, the line might be blurry.

- 18.

E.g. the homepage of booking.com displays photos of some elected cities that the user can click on to get to accommodation offers in that city or under the headline “Homes guest love” displays a choice of accommodation options in different places.

- 19.

E.g. on the Amazon homepage, one finds a number recommendations sorted in categories. When a user is logged in, some recommendation categories are based on prior user behaviour (e.g. “Keep shopping for” or “Buy again”), while others are not and seem to address everyone (e.g. “Top Deal” or “Amazon devices”).

- 20.

For example, collaborative filtering and community-based recommending cannot make statements about new products.

- 21.

Article 4(4) GDPR: “‘profiling’ means any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person, in particular to analyse or predict aspects concerning that natural person’s performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behaviour, location or movements.”

- 22.

Sometimes, however, the term is used in a broader sense. For example, Faden and Beauchamp use the term to describe any influence that is neither coercive nor persuasive and distinguish between manipulative influences that are controlling (incompatible with the autonomy of the influenced) and those manipulations that are non-controlling (compatible with the other’s autonomy) (Faden and Beauchamp 1986).

- 23.

Cf. Kant 2016: For autonomy, the human will, which permits a moral self-legislation that (according to the principle of the categorical imperative) is at the same time suitable as a universally valid legislation, is the condition for man to be able to regard himself and others as ends in themselves and not merely as means.

- 24.

See “manipulation” in Cambridge Dictionary; cf. also “Manipulation” in Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache, (accessed 13 January 2022).

- 25.

Sunstein expresses some doubt as to whether manipulation is a unitary concept after all and admits that his own account might not be exhaustive (Sunstein 2016); Ackerman describes manipulation as a term of combinatorial vagueness (with reference to Alston 1967) to which no enlisted condition is sufficient or necessary (Ackerman 1995).

- 26.

- 27.

For Susser et al. covertness is even the defining feature that makes manipulation distinctive (Susser et al. 2019b): “Strictly speaking, the only necessary condition of manipulation is that the influence is hidden; targeting and exploiting vulnerabilities are the means through which a hidden influence is imposed.” They argue that attempted covertness is crucial because when the decision-maker is aware of the influencers strategy that knowledge becomes part of the decision-making-process.

- 28.

What is typically hidden is not the “manipulative stimulus” but the “manipulative mechanism”, Spencer 2020: “For example, an actor trying to exploit the anchoring bias must make the anchor visible to the subject. This anchor is the stimulus, and it cannot be hidden. What is hidden from the subject, however, is the manipulative mechanism – the cognitive process that drives her estimate toward the anchor.”

- 29.

See for example Faden and Beauchamp 1986: Reducing or increasing options, making them more or less attractive, altering the understanding of a situation to modify the perception of options, and influencing “belief or behavior by causing changes in mental processes other than those involved in understanding,” can be ways to manipulate.

- 30.

Noggle identifies three levers that a manipulator can “adjust”: beliefs, emotions and desires (Noggle 1996).

- 31.

Noggle 1996: “It’s as though the manipulator controls his victim by ‘adjusting her psychological levers’.”

- 32.

Noggle writes: “The term “manipulation” suggests that the victim is treated as though she were some sort of object or machine” (Noggle 1996). Scanlon says: “An autonomous person cannot accept without independent consideration the judgment of others as to what he should believe or what he should do. He may rely on the judgment of others, but when he does so he must be prepared to advance independent reasons for thinking their judgment likely to be correct, and to weigh the evidential value of their opinion against contrary evidence” (Scanlon 1972).

- 33.

- 34.

To leave out for example family relationships with duties of care. In such personal or intimate relationships, a different assessment may be in order in the individual cases.

- 35.

- 36.

See the entry “recommendation” in the Lexico English Dictionary: https://www.lexico.com/definition/recommendation

- 37.

Which would usually be buying a good and relevant product for a fair price.

- 38.

- 39.

Sunstein finds that information on what other people do can be part of reflective deliberation (Sunstein 2016).

- 40.

Also Susser et al. do not consider merely informational nudges as manipulative (Susser et al. 2019b).

- 41.

See for exceptions below: 6.5.3.2.3. Addressing fears through (allegedly) harm-alleviating offers.

- 42.

See below: 6.5.3.2.3. Addressing fears through (allegedly) harm-alleviating offers.

- 43.

- 44.

Article 6 (1) lit. a GDPR.

- 45.

Of course, some of this information can only be used if the used devices record voce or eye-movement which usually requires that the user allows it or actively uses these functions (e.g., to speak with a “digital assistant” like Alexa, Siri etc.).

- 46.

Calo 2014: “[T]he concern is that hyper-rational actors armed with the ability to design most elements of the transaction will approach the consumer of the future at the precise time and in the exact way that tends to Guarantee a Moment of (profitable) Irrationality”.

- 47.

Doubting as well, Calo 2014.

- 48.

Including service for data offers.

- 49.

In this context, it is already questionable whether basing recommendations on emotions could count as manipulative, because taking a decision e.g. on music to hear according to one’s emotions is rather reasonable and in the users’ interest. There is no hidden strategy involved, when a platform recommends music, that the user is probably going to like in her emotional state.

- 50.

The right to withdrawal is limited in time (article 9 CR-D) and consumer need to return the received good on his own expense (article 14 CR-D).

- 51.

Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market and amending Council Directive 84/450/EEC, Directives 97/7/EC, 98/27/EC, and 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, here: UCP-D).

- 52.

E.g. if recommendations are headed with “customers who bought this item, also bought…”, this statement must be true; or when a recommended item is labelled as a “bestseller” it must be a bestseller.

- 53.

As a part of the “New Deal for Consumers” the European Parliament and the Council have delivered a new Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of 27 November 2019 amending the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Directive 2005/29/EC) to achieve a better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules. A consolidated version of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (2005/29/EC) as amended by Directive 2019/2161/EU is available under https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2005/29/2022-05-28. The new rules must be implemented into member states’ law and be applied from 28 May 2022 onwards.

- 54.

According to article 7 (4a) s. 2 UCP-D, “[t]his paragraph does not apply to providers of online search engines as defined in point (6) of article 2 of Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of the European Parliament and of the Council”.

- 55.

Platforms are not required to lay open their algorithms but rather to provide a general description on the default settings that determine the ranking, Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019, Rec. 22 ff. Article 85 German MStV contains a similar provision regarding media content.

- 56.

Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on consumer rights, amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directive 1999/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Council Directive 85/577/EEC and Directive 97/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council.

- 57.

Article 5 of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 (P2B Regulation) obliges platforms to make ranking criteria transparent towards businesses using the platform to market their products and services, so they know what they can do to achieve better rankings.

- 58.

In a way, they even go beyond what was necessary to protect consumers’ autonomous decisions when they also require platforms to lay open expected criteria. However, requiring transparency on all ranking criteria allows consumers to make more informed decisions without putting a heavy burden on the operators of the recommender system or the platforms. From this perspective, the transparency obligation is surely welcome. Search engines are regulated by Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services (P2B Regulation).

- 59.

In the online context, it becomes less and less obvious that only consumers need certain protection and not also agents acting in a commercial interest, e.g. as proxy for a small or medium-sized company. But this is a matter that goes beyond the scope of this paper. Apart from that, in practice it is likely that also commercially acting agents will sufficiently benefit from these transparency rules, at least, as long as they use the same platforms used also by consumers.

- 60.

Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market For Digital Services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act), OJ L 277/1.

- 61.

That means either, where the user can choose criteria for the relative order of the recommendations (on shopping sites such criteria are typically e.g. price, popularity, sustainability of the products, on travel booking sites criteria are typically price, location of hotels, in the case of travel by public transport, the number of intermediate stops or the duration of the trip) or where she can choose the method used, see footnote 20 ff.

- 62.

Article 27 (3) DSA.

- 63.

Art. 3 lit. r DSA defines advertisement as “information designed to promote the message of a legal or natural person, irrespective of whether to achieve commercial or non-commercial purposes, and presented by an online platform on its online interface against remuneration specifically for promoting that information”.

- 64.

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).

- 65.

Defined in article 4 (4) GDPR as “‘biometric data’ means personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic data”.

- 66.

The GDPR does not apply to anonymous data, rec. 26s. 6 GDPR.

- 67.

Considering that this decision must usually be taken several times a day on different platforms, websites and in apps.

- 68.

Article 9 (2) GDPR contains more exceptions for the prohibition to process sensitive date, but none of them would be applicable in the cases this paper is concerned with.

- 69.

The practice of personalized pricing shows that financial information is used by platforms (c.f. OECD 2018).

- 70.

Giving consent is usually just a click that users often undertake without real awareness of what exactly they are consenting to (c.f. also footnote 68) and also consent is not needed under all circumstances.

- 71.

Something that deviates from the normal course of events (Köhler 2021: UWG § 4a Rn. 1.89).

- 72.

Article 2 lit. j UCP-D.

- 73.

CJEU case C-628/17: Judgment of the Court (Fifth Chamber) of 12 June 2019, Presez Urzędu Ochrony Konkurencji i Konsumentów v Orange Polska S. A., paras 32, 46. The pressure must be of a kind that an average consumer is likely to not withstand it. That is the case if the average consumer assumes that he/she cannot escape the pressure and therefore considers behaving in the way the company wants, in order to avoid a threatened disadvantage (Köhler 2021: UWG § 4a Rn. 1.60).

- 74.

Article 24 (1b) Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 20 January 2022 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (2020/0361(COD)), P9_TA(2022)0014.

- 75.

For the distinction between input data for profiling and inferred data see Lorentz 2020.

- 76.

Article 3 (34) draft AI-A: “‘emotion recognition system’ means an AI system for the purpose of identifying or inferring emotions or intentions of natural persons on the basis of their biometric data”.

- 77.

Proposal COM/2021/206 final for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union legislative acts.

- 78.

Article 5 (1) li. a + b D-AI Act prohibits certain Ai deployments. But though recommender systems may fall under the AI definition and recommendations based on emotion recognition can be taken to be subliminal techniques, recommendations are unlikely to cause physical or psychological harm (Miotto Lopes and Chen 2022).

- 79.

According to article 6 D-AI-Act.

- 80.

See Proposal COM/2021/206 final for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union legislative acts, Explanatory Memorandum, 5.2.4.

- 81.

The other cases of avoidance do not play a role in connection with recommendation systems.

- 82.

See above footnote 50.

- 83.

One can put forward different reasons why personalised advertising should generally be prohibited, in particular one can have something against the underlying profiling. But from the perspective of private autonomy, targeted and personalized advertisement is only problematic if used in a manipulative way and is hence a danger to autonomy.

- 84.

Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act) contains a number of restrictions for “gatekeepers”, see especially Art. 6 (5).

References

Ackerman, F. 1995. The Concept of Manipulativeness. Philosophical Perspectives 9: 335–340. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2214225.

Aguirre, E., D. Mahr, D. Grewal, K. De Ruyter, and M. Wetzels. 2015. Unraveling the Personalization Paradox: The Effect of Information Collection and Trust-Building Strategies on Online Advertisement Effectiveness. Journal of Retail 91 (1): 34–49.

Alston, W.P. 1967. Vagueness. In The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. P. Edwards, vol. 8, 218–220. New York: Collier-Macmillan.

Barnhill, A. 2014. What is Manipulation? In Manipulation: Theory and Practice, ed. C. Coons and M. Weber. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199338207.001.0001/acprof-9780199338207-chapter-3.

Beam, M.A. 2014. Automating the News: How Personalized News Recommender System Design Choices Impact News Reception. Communication Research 41 (8): 1019–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0093650213497979.