Abstract

Temporary labour migration is known to be one of the most important livelihood options used by the poorest sectors of society in a variety of contexts, in developing countries, including India. Using large-scale data from the Indian National Sample Survey, 2007–2008, this chapter tries to explain the structure and flow of temporary labour migration, and its relationship with caste. The results suggest that the highest share of temporary labour migrants is found among rural to urban migrants (63%), and that there is a dominance of inter-state migration, particularly from the under-developed states of Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh. Our analysis corroborates earlier studies and shows that temporary labour migration rates are higher at the national level among the most disadvantaged social groups, namely the Scheduled Tribes (STs) and the Scheduled Castes (SCs) (45 and 24 per 1000 respectively) compared to Other Backward Classes (19 per 1000) and Others (12 per 1000). Our analysis shows that temporary labour migration rates were twice as high among the poorest of the poor as any other caste group. The findings point to a strong link between caste and temporary migration in India.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

As the foremost motive behind migration is employment, several theories have been put forwarded to understand the diverse economic, geographical and social factors behind this (Harris & Todaro, 1970; Massey et al., 1993; Todaro, 1976). It is well established that temporary labour migration is one of the most significant livelihood strategies adopted by the poorest sections of the society across a variety of developing country contexts, including India (Rajan, 2011; Asfaw et al., 2010; Brauw, 2007; Deshingkar, 2006; Deshingkar & Grimm, 2005; Ha et al., 2009; Keshri & Bhagat, 2013; Lam et al., 2007; Pham & Hill, 2008). It has been given various nomenclatures, for instance, circular migration, short-term migration and seasonal migration (Rajan & Sumeetha, 2020; Coffey et al., 2015; Deshingkar & Farrington, 2009; Haberfeld et al., 1999; Hugo, 1982). The recent outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by lockdown driven migration crisis which affected temporary migrants bitterly (Bhagat et al., 2020; Rajan et al., 2020b). It really enhances the need to understand the different aspects of labour migration which can help sensitise policy makers and government agencies towards the problems of migrants, which really had no hint of the magnitude of migrant labours staying in the urban areas.

Several studies have delved into the factors which are associated with temporary labour migration, such as age, sex, educational attainment, caste/social-group, religion, size of land possession and poverty in different parts of India (Coffey et al., 2015; Dodd et al., 2016; Keshri, 2019; Sucharita, 2020). In the Indian context social factors, especially, caste is very important determinant of any kind of migration as economic condition is determined by the caste of the person. The origin of caste system is assumed to be more than 2000 years ago. A caste is an endogamous social group in India that governs the status of an individual born into it. It has been evolved out of the four-fold Varna categories with Brahmins at the top followed by Kshathriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras at the bottom (Bhagat, 2006). Understanding the historical injustice experienced by the Sudras and Adivasis (tribal communities) after independence, the Indian Constitution designated some castes and tribes at the bottom of the caste hierarchy as Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), and after 1990, a group of castes whose position was better than the SCs and the STs, but worse than the others were designated as Other Backward Classes (OBCs). Reservations and quotas in education and employment are available to all of them as a kind of affirmative actions. Several studies have looked into the relationship between income disparity and caste divisions using large scale survey data (Deshpande, 2011; Desai & Dubey, 2011; Subramanian & Jayaraj, 2006; Zacharias & Vakalubharanam, 2011; Rajan et al., 2020a, b). For instance, despite absence of reliable data on caste Deshpande (2011) tried to dig out facts using the National Sample Survey and the National Family Health Survey shown that how the social identity matters in the private sector jobs and relationship between caste and wage gaps in the urban areas.

In various research, caste has been demonstrated to be a key factor in determining migration patterns (Abraham & Subramanian, 1974; Chandrasekhar & Mitra, 2018; Kumar et al., 2009; Vartak & Tumbe, 2020). Some village-level studies have also attempted to comprehend the caste-migration relationship (Fuller & Narasimhan, 2008; Jain & Sharma, 2019; Rogaly et al., 2001; Srivastava, 1989; Vartak, 2016). Deshingkar and Farrington (2009) found in their study that the caste-based discrimination is one of the important push factors which force migrants from rural India. Kunduri (2018), further, adds other domain of caste and migration relationship based on her field work that SCs cannot get better jobs due to their caste identity even after migrating to cities and they have no choice but to do the menial jobs of sweepers and cleaners. In addition to this, in a recent study based in the Indian capital city Delhi, Agarwal (2022) has found that migrants could not escape discrimination in their urban destination too as due to its presence they face lot of difficulties in accessing the benefits of welfare schemes of Government. In their regional migration survey in Eastern Uttar Pradesh and Northern Bihar, which was based on more than 4000 households, Roy et al. (2021) found caste as a significant predictor of migration and the prevalence of seasonal migration in population was found disproportionately higher among SCs than other caste groups, though OBCs and general caste people had comparatively higher percentage as far as permanent and international migration were concerned.

Nonetheless, we cannot identify a recent study that has used nationally representative large-scale survey data to analyse temporary labour mobility through a caste lens. Using large-scale data from the Indian National Sample Survey, this chapter attempts to explain the pattern and flow of temporary labour migration, as well as the relationship between caste and temporary labour migration, at the national and state levels in India.

2 Data and Methods

The present study employed the Unit Level Data of the 64th round (2007–08) of the Indian National Sample Survey (NSS). This large-scale nationally representative household survey was conducted in all the States and Union Territories during 2007–2008, which is the only recent national and state level survey on temporary labour migration available. The survey covered a sample of 1,25,578 households and 5,72,254 persons. The ‘Employment & Unemployment and Migration Particulars’ Schedule was used to collect data on several different aspects of migration (National Sample Survey Office, 2010).

Information regarding temporary labour migrants was collected by enquiring whether a household member had stayed away from the village/town, during the last 365 days, for employment or in search of employment for a period of 30 days to 6 months. We identified temporary labour migration streams (rural to rural, rural to urban, urban to urban, and urban to rural) by looking at the destination for the longest spell (a spell was defined as a period of staying away from the village/town for 15 days or longer). The destination could be in the same district (rural or urban), in the same state but in a different district (rural or urban), or in a different state (rural or urban). Migration rates were calculated to study the intensity of migration. Migration rates for any specific category of people was estimated by dividing the number of persons migrating of that specific category from that region and during the specified period of time by 1000 persons of the specific category in that region.

The main independent variable –caste,Footnote 1 has been categorised into Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Others, following the definitions used in the earlier studies (Bhagat, 2006; Zacharias & Vakalubharanam, 2011). The information on monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE) has been used to understand the association between economic status and temporary labour migration disaggregated by caste. For all the analyses, the working age group (15–64 years) has been considered and we have used Stata 12 statistical package for this.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Pattern of Temporary Labour Migration

Streams of temporary labour movement across key states are provided in this section to help understand migration patterns and flows (Table 7.1). Overall, the rural to urban stream has the biggest proportion of temporary labour migrants (63 percent), and the rural-to-rural stream the second most important stream of migration (with 30 percent of the migrants), while the urban to rural and urban to urban streams have a small share of migrants (2 percent and 5 percent respectively). The vast majority of migrants seeking a better life in cities came from the rural hinterland (Agarwal, 2016) and they work in the informal sector in cities, such as construction sites, brick kilns, transportation, and as casual labour, whereas rural to rural migrants work in agriculture, plantations, quarries, and fishing (Chandrashekhar & Mitra, 2018; Deshingkar & Akter, 2009; Rogaly et al. 2002).

The break-up of temporary labour migrants by streams of migration across the states shows large deviations from national average in several states. For example, in Chhattisgarh, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh, more than three-fourth of the temporary labour migrants belong to rural to urban stream (82%, 81%, and 80% respectively). In Assam, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal, the share of rural to urban stream is higher than the national average of 62 per cent. The plausible explanation of such kind pattern is that most of these states are backward and less urbanized which leads to seasonal unemployment (Datta, 2023; Kumar & Bhagat, 2017; Sucharita, 2020). On the other hand, in Kerala and Odisha, minor differences are found in rural to rural and rural to urban streams, while in Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat almost equal proportion of migrants are found in both the streams. Interestingly, in some southern states, namely, Tamil Nadu and Kerala more than 10 per cent of the temporary labour migrants belong to urban-to-urban migration stream, which is at variance with the general pattern. This may be due to higher level of urbanization in these states.

As we know that temporary labour migrants generally travel short distances for work, however, if there are already established social networks then they do not hesitate to migrate to longer distance destinations and even to the other states. Therefore, we have tried to comprehend the within state and out of state flow of temporary labour migration by place of residence which is presented in Table 7.2.

Among the underdeveloped states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh, out of state migration is more than two-third of the total temporary labour migrants (83%, 74%, and 61% respectively), while in Chhattisgarh and Punjab, out of state migration is slightly more than half (56% and 57% respectively). On the other hand, in most of the developed states, namely, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, more than three-fourth of temporary labour migrants circulate within the state (97%, 84%, 77%, 73%, and 70% respectively). However, Assam may be an exception as it is a backward state with roughly similar results (83%). In rural areas the results are almost identical to the overall figures, yet in urban areas some deviations can be observed. This pattern is supported by the fact that inter-state temporary labour migration, which is mostly a livelihood strategy and governed by the economic development and variations in the demographic transition of states (Srivastava et al., 2020). Also, among the states, migration is more prevalent among the developed states which have ample employment opportunities in the cities for their migrants.

3.2 Caste as a Determinant of Temporary Labour Migration

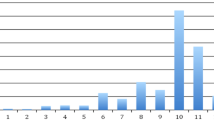

Results suggest that high temporary labour migration rates are observed at the national level among the most disadvantaged social groups, namely the Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes (45 and 24 per 1000 respectively) while it is comparatively lower among the Other Backward Classes (19 per 1000) and the Others (12 per 1000). In rural areas steep differences across caste have been observed, which are absent in urban areas mostly because the intensity of this kind of migration is less in urban areas, and also because caste is less important in urban life (Fig. 7.1).

Moreover, variations across the states are noteworthy. To elaborate, in Gujarat, the temporary labour migration rate is 160 migrants per thousand among STs, which is the highest in any of the Indian states (Table 7.3). This high rate is due to the presence of some hilly and tribal districts in Gujarat which are historically known for the seasonal migration (Breman, 2007). It suggests that even after many decades of independence of India tribal population is living in abject poverty even in economically developed state like Gujarat. It is followed by similar migration rates among the STs in Madhya Pradesh (71) and West Bengal (58). Further, there is a high migration rate among SCs in Jharkhand (65), Bihar (58), Madhya Pradesh (45), Rajasthan (35), and Chhattisgarh (32). In Bihar, earlier studies have also found a similar pattern of migration among SCs as these people use migration as a strategy to break away from the oppressive caste system (Deshingkar, 2006; Kumar & Bhagat, 2017; Datta, 2023). It is also worth noting that the OBCs have a substantially high migration rate in Bihar, with 51 migrants per thousand. Bihar has a typical pattern of seasonal out-migration, in which non-land-holding OBCs’ living conditions are very bad due to the tiny scale of the agriculture economy, due to which they travel to different regions of the country for better livelihood (Kumar & Bhagat, 2017; Roy et al., 2021).

Furthermore, variations due to place of residence could also be observed across the states (Table 7.3). Results suggest that among STs, temporary migration rate is the highest in the rural areas of Gujarat (176), which is more than twice the migration rate of the second ranking state Madhya Pradesh (75). It is followed by West Bengal (62), Andhra Pradesh (44), and Jharkhand (43). Among SCs the highest migration rate is observed in rural Jharkhand (73) which is followed by Bihar (61), Madhya Pradesh (56), and Rajasthan (41).

Interestingly, among the OBCs, higher migration rate is noted in rural Bihar with 56 migrants per thousand respectively, which are comparatively higher than that of the other states. Other states with high migration rate among OBCs in rural areas are Jharkhand (40), Madhya Pradesh (29), West Bengal (29), and Gujarat (23). Among others, the highest migration rate is observed in Bihar (43), Chhattisgarh (40), West Bengal (38), and Jharkhand (24). In urban areas migration rate is relatively very low in all the social groups in most of the states with some exceptions like, Assam where the migration rate is 29 migrants per thousand among OBCs and almost 15 migrants per thousand among each of the STs and others. This pattern could be explained by the fact that in urban areas migrants mostly migrate on permanent or semi-permanent basis rather than temporary basis.

We also tried to figure out how caste and migration relate to gender, and the results are intriguing. Despite the fact that female participation in temporary migration is lower, ST women and girls are three times more likely to migrate than the other social categories, indicating the deprivation of the former (Fig. 7.2). It could also be explained by the fact that women who do not own any agricultural land migrate more (Heyer, 2016), which is a regular occurrence in tribal areas. It has also been discovered that the majority of women from the SCs and STs engage in circular migration (Mazumdar et al., 2013).

To further investigate the trade-off of income with migration, we have used MPCE quintiles as a proxy for the indicator of income. The prevalence of temporary labour migration among the impoverished social groups of STs is nearly two times greater than the other social groups among lower income categories, especially the lowest and lower quintiles (Fig. 7.3). The gradient of change in prevalence, on the other hand, is not very steep in the medium, higher, and highest quintiles. It once again emphasises the relevance of caste in migratory decisions.

4 Discussion and Conclusion

Internal labour migration has remained inevitable despite the recent impact of globalization and enhancement of transport facilities between countries. It is entrenched that temporary labour migration is one of the most significant livelihood strategies adopted by the poorest sections in developing countries including India (Rajan, 2020a, b; Keshri & Bhagat, 2012; Keshri & Bhagat, 2013). Several village-level studies have established that temporary labour migration is rural in nature and caste is one of the important determining factors as far as rural areas are concerned, however we do not find any recent study which has attempted to understand temporary labour migration through a caste lens at the national level. Therefore, this chapter is an important contribution towards this aspect of migration research. Overall, the rural to urban migration stream has the biggest proportion of temporary migrants, indicating a lack of employment possibilities in India’s undeveloped regions, particularly the forested, hilly, and tribal areas, from which people are forced to migrate to other states in quest of work. It is also reflected in the results from the underdeveloped states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh, out of state migration is more than two-third of the total temporary labour migrants (83%, 74%, and 61% respectively). Roy et al. (2021) have found that temporary labour migrants from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, apart from push factors at origin, also find some support from their existing social networks in form of their friends and relatives who are already settled in the destination states, it really helps them in deciding their first move.

Higher prevalence of temporary labour migrants are observed at the national level among the most disadvantaged social groups, namely the STs and SCs (45 and 24 per 1000 respectively) while it is comparatively lesser among OBCs (19 per 1000) and Others (12 per 1000). Among the major states in Bihar temporary labour migrants was highest among SCs (58.2 per 1000) similar kind of results have been observed in a recent study from Bihar (Datta, 2023; Roy et al., 2021). Even in industrialised states like Gujarat, the situation of STs in rural areas is poor, as they are forced to relocate within the state in quest of work. This is found mostly hilly and tribal districts in Gujarat which are historically known for the seasonal migration (Breman, 2007). It suggests that even after many decades of independence of India tribal population is living in abject poverty even in economically developed state like Gujarat. It is important to note that in rural areas caste is found to be an important determining factor but in urban areas we do not find any significant deviation on the prevalence of temporary labour migration as far as caste is concerned. Among women, overall temporary labour migration is less but among STs women it is significantly higher as compared to women of other castes. It is noteworthy that among the poorest of the poor section of the society, temporary labour migration is twice that of any other caste group. Results suggest an obvious predominance of caste as a determining factor for migration in India.

These results can be useful for policymakers particularly during formulation of the social protection schemes for temporary labour migrants in urban areas. As we already know that the recent outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by lockdown driven migration crisis which affected temporary migrants bitterly (Bhagat et al., 2020; Rajan et al., 2020b). It has been found that measures of social protection and rehabilitation schemes during COVID-19 did not reach to the needy, even the portability of ration card in the developed states like Delhi could not be implemented as found in a recent study in Delhi (Agarwal, 2022). Several studies have found that temporary migrants have suffered in the urban areas during the lockdown and particularly the poorest of the poor and people belonging to disadvantaged caste groups (Mishra et al., 2020; Rajan et al., 2020b).

Notes

- 1.

Due to the way that the NSS data are organised, under caste we include not only the four varna castes but also the Schedule Castes which includes Dalits as well as the Scheduled Tribes which are technically not included in the caste hierarchy.

References

Abraham, M. F., & Subramanian, R. (1974). Patterns of social mobility and migration in a caste society. International Review of Modern Sociology, 4(1), 78–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41420512

Agarwal, S. (2016). Urban migration and social exclusion: Study from Indore slums and informal settlements. Available at SSRN 2771383.

Agarwal, P. (2022). State-Migrant relations in India: Internal migration, welfare rights and COVID-19. Social Change, 52(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/00490857221094351

Asfaw, W., Tolossa, D., & Zeleke, G. (2010). Causes and impacts of seasonal migration on rural livelihoods: Case studies from Amhara region in Ethiopia. NorskGeografiskTidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography, 64(1), 58–70.

Bhagat, R. B. (2006). Census and caste enumeration: British legacy and contemporary practice in India. Genus, 62, 119–134.

Bhagat, R. B., R.S., R., Sahoo, H., Roy, A. K., & Govil, D. (2020). The COVID-19, migration and livelihood in India: Challenges and policy issues: Challenges and policy issues. Migration Letters, 17(5), 705–718.

Brauw, A. D. (2007). Seasonal migration and agriculture in Vietnam. ESA Working Paper No. 07–04. Rome: Agricultural Development Economics Division: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO – ESA).

Breman, J. (2007). Labour bondage in West India: From past to present. Oxford University Press.

Chandrasekhar, S., & Mitra, A. (2018). Migration, caste and livelihood: Evidence from Indian city-slums. Urban Research & Practice, 12(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2018.1426781

Coffey, D., Papp, J., & Spears, D. (2015). Short-Term Labor Migration from Rural North India: Evidence from New Survey Data. Population Research and Policy Review, 34, 361–380.

Datta, A. (2023). Migration and Development in India: The Bihar Experience. Routledge.

Desai, S., & Dubey, A. (2011). Caste in 21st century India: Competing narratives. Economic and Political Weekly, 46(11), 40–49.

Deshingkar, P. (2006). Internal migration, poverty and development in Asia. Briefing paper. Overseas Development Institute.

Deshingkar, P., & Akter, S. (2009). Migration and human development in India. Published in: Human Development Research Paper (HDRP) Series, Vol. 13, No. 2009.

Deshingkar, P., & Farrington, J. (2009). Circular migration and multilocational Livelihood strategies in rural India. Oxford University Press.

Deshingkar, P. & Grimm, S. (2005). Internal migration and development: A global perspective. Paper prepared for International Organization for Migration (IOM). Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Deshpande, A. (2011). The Grammar of caste: Economic discrimination in contemporary India. Oxford University Press.

Dodd, W., Humphries, S., Patel, K., Majowicz, S., & Dewey, C. (2016). Determinants of temporary labour migration in southern India. Asian Population Studies, 12(3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2016.1207929

Fuller, C. J., & Narasimhan, H. (2008). From Landlords to Software Engineers: Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 50(1), 170–196. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27563659

Ha, W., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2009). Inequality and internal migration in China: Evidence from village panel data. Human Development Research Paper. United Nations Development Programme.

Haberfeld, Y., Menaria, R. K., Sahoo, B. B., & Vyas, R. N. (1999). Seasonal migration of rural labour in India. Population Research and Policy Review, 18, 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006363628308

Harris, J., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment, and development: A two sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60, 126–142.

Heyer, J. (2016). Rural Gounders on the move in western Tamil Nadu: 1981–2 to 2008–9.

Hugo, G. J. (1982). Circular migration in Indonesia. Population and Development Review, 8(1), 59–83.

Jain, P., & Sharma, A. (2019). Super-exploitation of Adivasi Migrant Workers: The Political Economy of Migration from Southern Rajasthan to Gujarat. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 31(1), 63–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0260107918776569

Keshri, K. (2019). Temporary labour migration. In S. I. Rajan & M. Sumeetha (Eds.), Handbook of internal migration in India (pp. 140–152). SAGE India.

Keshri, K., & Bhagat, R. B. (2012). Temporary and seasonal migration: Regional pattern, characteristics and associated factors. Economic & Political Weekly, 47, 81–88.

Keshri, K., & Bhagat, R. B. (2013). Socioeconomic determinants of temporary labour migration in India: A regional analysis. Asian Population Studies, 9, 81–88.

Kumar, N., & Bhagat, R. B. (2017). Interaction between migration and development: A study of income and workforce diversification in rural Bihar. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 8(1), 20–136.

Kumar, R., Kumar, S., & Mitra, A. (2009). Social and Economic Inequalities: Contemporary Significance of Caste in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 44(50), 55–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25663890

Kunduri, E. (2018). Between Khet (field) and Factory, Gaanv (village) and Shehar (city): Caste, Gender and the (Re)shaping of Migrant Identities in India. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 19, 1–39.

Lam, T. Q., John, B. R., Chamratrithirong, A., & Sawangdee, Y. (2007). Labour migration in Kanchanaburi demographic surveillance system: Characteristics and determinants. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 16, 117–144.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population & Development Review, 19, 431–466.

Mazumdar, I., Neetha, N., & Agnihotri, I. (2013). Migration and Gender in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 48(10), 54–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23391360

Mishra, S. V., Gayen, A., & Haque, S. M. (2020). COVID-19 and urban vulnerability in India. Habitat International, 103, 102230.

National Sample Survey Office. (2010). Migration in India. Report No. 533 (64/10.2/2), 2007–2008, National Sample Survey Organisation. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

Pham, B. N., & Hill, P. S. (2008). The role of temporary migration in rural household economic strategy in a transitional period for the economy of Vietnam. Asian Population Studies, 4, 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730801966683

Rajan, S. I. (2011). India Migration Report 2011: Migration, Identity and Conflict. Routledge.

Rajan, S. I. (2020a). Migrants at a crossroads: COVID-19 and challenges to migration. Migration and Development, 9(3), 323–330.

Rajan, S. I. (2020b). COVID-19-led migrant crisis. A critique of policies. Economic & Political Weekly, 55(48), 13–16.

Rajan, S. I., & Sumeetha, M. (2020). Handbook of Internal Migration in India. Sage.

Rajan, S. I., Zachariah, K. C., & Kumar, A. (2020a). Large-scale migration surveys: Replication of the Kerala model of migration surveys to India migration survey 2024. In S. Irudaya Rajan (Ed.), India migration report 2020: Kerala model of migration survey, chapter 1 (pp. 1–22). Routledge.

Rajan, S. I., Sivakumar, P., & Srinivasan, A. (2020b). The COVID-19 pandemic and internal labour migration in India: A ‘Crisis of Mobility’. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(4), 1021–1039.

Rogaly, B., Biswas, J., Coppard, D., Rafique, A., Rana, K., & Sengupta, A. (2001). Seasonal migration, social change and migrants' rights: Lessons from West Bengal. Economic & Political Weekly, 36, 4547–4559.

Rogaly, B., Coppard, D. Safique, A. Rana, K., Sengupta, A, & Biswas, J. (2002). Seasonal migration and welfare/illfare in Eastern India: A social analysis. The Journal of Development Studies, 38(5), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331322521

Roy, A. K., Bhagat, R. B., Das, K. C., Sarode, S., & Reshmi, R. S. (2021). A report on causes and consequences of out-migration from Middle Ganga Plain. Department of Migration and Urban Studies, International Institute for Population Sciences.

Srivastava, R. (1989). Interlinked modes of exploitation in Indian agriculture during transition: A case study. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 16(4), 493–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066158908438404

Srivastava, R., Keshri, K., Gaur, K. Padhi, B., & Jha, A. (2020). Internal migration in India and the Impact of Uneven Regional Development and Demographic Transition across States: A Study for Evidence-Based Policy Recommendations. A Study Report prepared for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Institute of Human Development.

Subramanian, S., & Jayaraj, D. (2006). The distribution of household wealth in India. Paper prepared for UNU-WIDER project meeting, Helsinki, May 4–6.

Sucharita, S. (2020). Socio-economic Determinants of Temporary Labour Migration in Western Jharkhand, India. Millennial Asia, 11(2), 226–251.

Todaro, M. P. (1976). Internal Migration in developing countries: A review of theory, evaluation, methodology, and research priorities. International Labour Office.

Vartak, K. (2016, June). Role of Caste in Migration: Some Observations from Beed District, Maharashtra. Social Science Spectrum, 2(2), 131–144.

Vartak, K., & Tumbe, C. (2020). Migration and caste. In S. Rajan & S. M. (Eds.), Handbook of internal migration in India (pp. 252–267). SAGE Publications Pvt Ltd.

Zacharias, A., & Vakulabharanam, V. (2011). Caste stratification and wealth inequality in India. World Development, 39, 1820–1833.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rajan, S.I., Keshri, K., Deshingkar, P. (2023). Understanding Temporary Labour Migration Through the Lens of Caste: India Case Study. In: Rajan, S.I. (eds) Migration in South Asia. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34194-6_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34194-6_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-34193-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-34194-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)