Abstract

This chapter aims to outline some of the future goals for fragility fracture care and to offer some thoughts on how some of the more significant challenges need to be approached. The increase in the prevalence of fragility fractures is a growing challenge. Globally, fragility fractures have a varied impact. In resource-rich nations, approximately 10–20% of patients move to residential care after a hip fracture, with accompanying financial and socioeconomic costs. Where healthcare services are less well resourced, much fragility fracture care takes place in the patient’s place of residence or that of their family; placing significant stress on their ability to cope. There is also a chronic worldwide shortage of nurses and, in specialties such as orthogeriatrics and fragility fracture management, there is also high patient acuity and high demand for expert care, often resulting in failure to meet patient and community needs. Care is complex and time and staff intensive, demanding staffing flexibility. Nursing care is likely to be missed when staffing ratios are low and when staffing flexibility is lacking. Inordinate energy must be spent in trying to provide care that meets constantly changing patient needs. Clinicians must also engage with governments, policy makers, leaders, employers, and communities to present evidence, lobby and negotiate for their own working conditions, and the care priorities of those for whom they provide care.

This chapter focuses on several aspects of the future development of fragility fracture and orthogeriatric care. This includes highlighting the need for new ways of working and nursing role development along with ensuring that care is provided by nurses who not only understand the injury and the acute care needs related to the fracture, but who also recognise the specific and complex needs relating to the frail older person with multiple comorbidities. Clinicians must also be skilled in chronic condition management, especially concerning osteoporosis and other comorbidities.

The evidence base for orthogeriatric and fragility fracture nursing is considered throughout this book. Expert care needs a specific and broad body of evidence that identifies exactly what its actions are and what its value is. Hence, the development, conduct, translation, and application of nursing research for the care of patients with fragility fractures is essential and needs to be developed with a global perspective.

Education is the foundation of transforming care and services so that patient outcomes following fragility fracture can be optimised and future fractures prevented. Even though nursing education is paramount in achieving optimum patient care, acknowledging that orthogeriatric and fragility fracture care is, by necessity, interdisciplinary is essential. The benefits of multidisciplinary approaches to care, supported by interdisciplinary education are considered here.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Orthogeriatric care

- Fragility fracture care

- Workforce

- Resources

- Nursing roles

- Chronic condition management

- Dignity

- Compassion

- Evidence base

- Education

18.1 Introduction

This book has explored the central concepts of orthogeriatric and fragility fracture care. It has taken a lead from the first edition but explored some aspects in more detail and updated the background and literature. While the focus has been on nursing care, the clinical role of other allied health professionals who collaborate with nurses as part of the interdisciplinary approach has also been outlined in recognition of the developing interdisciplinary approach so important to effective management and care—even though much clinical practice globally is not yet as collaborative as it ought to be. Some new topics have been incorporated along with updated ideas, theory, and evidence. The authors include clinical nurses, educators, and researchers from the complete patient journey with collaboration and additional input from colleagues who are physiotherapists, dietetic practitioners, psychologists, physicians, and surgeons, reflecting the acute, surgical, rehabilitation, and secondary prevention aspects of the care pathway.

Although this book is aimed at nurses working in any setting around the globe where people with fragility fractures receive care, we have tried to broaden the audience for the book to other health professionals who are part of the orthogeriatric/fragility fracture interdisciplinary team. Throughout ‘practitioners’ are referred to, capturing the diversity of roles in orthogeriatric and fragility fracture teams. However, because nurses make up such a large proportion of the workforce working with patients with fragility fractures, specific nursing aspects are discussed throughout the book. Nurses are active across the complete pathway with potential to significantly and positively influence care outcomes.

Practice, resources, attitudes, and culture vary around the world and practitioners in different localities face different challenges. For nurses and their interdisciplinary team colleagues to provide evidenced-based, high-quality care they need to not only have an understanding of their own roles but also the roles and value of their team colleagues and how each impact on patient outcomes throughout the pathway.

The role of nurses and other practitioners in orthogeriatric care and fragility fracture management and care (definitions are provided in Chap. 1) is as broad and complex as are the characteristics of the older people with whom they work, in the community and hospital, in times of acute need and throughout their lifespan following a first fragility fracture.

This final chapter aims to outline some of the future goals for fragility fracture care and to offer some thoughts on how some of the more significant challenges need to be approached.

18.2 The Future Impact of the Fragility Fracture Epidemic

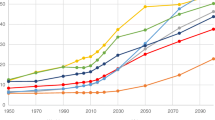

The rising incidence of fractures, particularly fragility fractures, is a global public health issue [1]. As the global population continues to age, it is anticipated that the world will see an increase, not only in the number of people presenting with a fragility fracture, but also in the complexity and frailty of those with the fracture. It has been estimated that there is one fragility fracture worldwide every 3 s, equating to 25,000 per day [2] almost always resulting in attendance at an emergency department and either admission to hospital or a general practitioner or clinic visit. This places unprecedented and constant pressure on every aspect of health and social care services in every country.

Veronese et al. [3] explored the epidemiology of fragility fractures and their social impact, outlining both the costs of healthcare and the devastating social costs of fractures, particularly those of the hip and vertebrae. They illustrated how hospital costs for hip fracture are similar to other diseases requiring high hospitalisation rates (e.g. cardiovascular disease, stroke) but are dwarfed by social costs and impacts because of the onset of new comorbidities, sarcopenia, fraility, loss of function and independence, poor quality of life, disability and mortality following fractures.

The ageing of the population and the associated increase in the prevalence of fragility fractures is a growing challenge for healthcare services, placing pressure on resources and ongoing social care demands because of the negative impact on quality of life, functional ability, and independence. While all fragility fractures have a varied impact, the significant impact on those falling and fracturing their hip has been explored by Dyer et al. [4] who identified that, in resource-rich nations, approximately 10–20% of patients move to residential care after a hip fracture, with accompanying financial and socioeconomic costs. Although in middle- and low-income countries, these issues have yet to be explored as data is more difficult to collect, it can be hypothesised that where healthcare services are less well resourced, most fragility fracture care takes place in the patient’s place of residence or that of their family; placing significant stress on their ability to cope in a setting where surgery might not be available and creating a situation in which outcomes for the person suffering the fracture are very poor.

For all members of the orthogeriatric/fragility fracture interdisciplinary team, it is essential to embrace the values (vision and mission) of the Fragility Fracture Network (https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/) (see Box 18.1) so that prevention and management of fragility fractures everywhere in the world can move in a positive direction. The following sections illuminate some of the considerations in achieving these bold plans.

Box 18.1 The Fragility Fracture Network Values [5]

Vision

A world where anybody who sustains a fragility fracture achieves the optimal recovery of independent function and quality of life, with no further fractures.

Mission

To optimise globally the multidisciplinary management of the patient with a fragility fracture, including secondary prevention.

18.3 Workforce and Resource Challenges

There is a chronic worldwide shortage of nurses: the World Health Organization [6] has estimated that the global shortage of nurses is in the region of 5.9 million; with the greatest gaps being in the poorest parts of the world, including countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America. There is a strong interdisciplinary relationship between nurses, doctors, and allied health professionals and, although the nursing shortage is undoubtedly a crisis, it is not in isolation. The World Health Organization has also identified a projected global shortage of ten million health workers by 2030, mostly in low- and low-middle income countries [7]. In specialties such as orthogeriatrics and fragility fracture management, however, where there is high patient acuity and high demand for expert care, this shortage of nurses and other team members results in failure to meet patient and community needs, making this a critical crisis.

The nursing shortage is due to a variety of factors including an ageing population, political ideologies for healthcare, education and resourcing problems, a decrease in the numbers entering the nursing profession, and a high nurse turnover rate. This has a direct impact on the quality of patient care; when there are insufficient nurses and other practitioners to care for patients, there is a longer wait for care and patients receive less care that is more likely to be of poor quality with a resultant effect on care outcomes. ‘Missed care’ or ‘care rationing’ occurs when nurses are unable to complete all care activities for patients because of scarcity of time and resources. Rationing of care or missed care negatively correlates with patient safety incidents and higher risk of complications and death for patients [8]. It has been shown that an increase in a nurses’ workload by one patient, from eight to nine patients per qualified nurse, increases the likelihood of an inpatient dying within 30 days of admission by 7% [9].

Given the nature of hip fractures, for example, and associated complexity of needs, care can be time and staff intensive, demanding staffing flexibility. A literature review [8] has highlighted that nursing care is more likely to be missed when staffing ratios are low and when staffing flexibility is lacking. Staffing flexibility involves the ability to provide additional staff with the right skills when needed, based on patient care needs.

The full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing work and recruitment and retention is currently unknown. During the pandemic, many services have had to adapt to meet the demands of the service; many elective services were halted; and nurses and other healthcare professional have worked in new ways including moving to unfamiliar areas of clinical practice. This has demonstrated the best of nurses and nursing, showing their resilience and desire to fulfil the fundamentals of nursing even when working under extreme conditions. Virginia Henderson [10] recognised that:

‘… the unique function of nurses in caring for individuals, sick or well, is to assess their responses to their health status and to assist them in the performance of those activities contributing to health or recovery or to dignified death that they would perform unaided if they had the necessary strength, will, or knowledge and to do this in such a way as to help them gain full of partial independence as rapidly as possible’.

For nurses, moving to an unfamiliar clinical area challenges them to perform tasks and activities for which they feel ill prepared, and it is important to recognise how these new and extremely challenging situations will have affected the nurses as individuals and professionals. Studies have shown that there have been significant levels of burn out for nurses working through the pandemic [11]; the impact this will have on ongoing recruitment and retention is likely to have a detrimental effect on health services’ ability to provide care long into the future. Orthogeriatric and fragility fracture services will need to develop approaches to this problem that will ensure quality of care is maintained and that outcomes continue to improve.

On a positive note, since the pandemic there have been reports of increased interest in pre-graduate applications for nursing courses and an increase in applications for entry to nursing. This is thought to be due to the positive portrayal of nurses and nursing during the pandemic. Although this will not resolve the nursing shortage, made worse by the pandemic, it means that recruitment of staff to orthogeriatric and fragility fracture services could improve in the future providing these services adapt to the needs of the new generation of nurses and ensure they are attractive places to work from the perspective of working conditions and education.

Nurses working in high acuity areas such as orthogeriatrics and fragility fracture care find themselves in a challenging situation. They must expend inordinate energy to provide care that meets patient needs and constantly have to adapt to the changing needs of patients, their families and communities. At the same time, they must also engage with governments, policy makers, leaders, employers, and communities to present evidence, lobby, and negotiate for their own working conditions and the care priorities of those for whom they provide care.

18.4 New Ways of Working and Nursing Role Development

The fundamental roles of nurses in the care of patients following fragility fractures are threefold:

-

Clinical care in the acute clinical episode.

-

Specialist advanced care throughout the patient pathway of care, from the first fragility fracture to, potentially, end of life care.

-

Care coordinators of orthogeriatric/fragility fracture interdisciplinary care.

For those working in orthogeriatric/hip fracture units, orthopaedic wards, inpatient rehabilitation units, or at home while restoring health and function, this book has tried to provide a comprehensive review of the fundamental knowledge and skills required to look after patients well in any of these settings. Nursing care of patients with fragility fractures is best provided by nurses who not only understand the injury and the acute care needs related to the fracture, but also recognise the specific and complex needs relating to the frail older person with multiple comorbidities.

The focus of interventions is to reduce the impact of the fracture and optimise recovery and subsequent outcomes. Demonstrating the positive impact of nursing care involves identifying those actions that are specifically related to nursing and finding ways to identify measurable nurse-sensitive indicators of care quality [12]. This will enable nurses and nursing to demonstrate its value despite the complexity of nursing activity.

The nursing role in fragility fracture care has been discussed throughout this book. It focuses on:

-

Pain management, by assessment and interventions such as administering medication, positioning/repositioning and comfort measures.

-

Optimising nutrition and hydration.

-

Identifying and treating delirium.

-

Prevention strategies for:

-

Venous thromboembolism.

-

Healthcare-associated infections.

-

Subsequent falls and injuries.

-

Skin damage and promoting wound healing.

-

Postoperative and opioid induced.

-

-

Assisting in early remobilisation and rehabilitation.

-

Integrating rehabilitation goals into all care activity.

-

Planning coordinating and implementing optimum discharge from hospital.

In the clinic/community/primary care setting, and after patients’ discharge from the hospital, the role of the nurse encompasses:

-

Continuing rehabilitation and optimisation of function.

-

Optimising adherence to osteoporosis treatment and other activities to prevent secondary fractures.

-

Falls prevention.

In some localities, care is enhanced by nurses working in advanced practice roles. These roles vary depending on the location, the local health system, local and national policy and guidance, and the culture, education, and empowerment of nurses in individual countries. Such roles often encompass advanced/specialist clinical practice, leadership, and education and can carry various titles that may include the following:

-

Nurse practitioners and Advanced Practice Nurses.

-

Hip fracture nurse specialists/advanced practitioners.

-

Fracture liaison nurse specialists or coordinators.

-

Osteoporosis nurse specialists.

-

Elderly/elder/older person care and frailty nurse specialists.

-

Trauma nurse coordinators.

These roles are usually undertaken by nurses, but not exclusively and may be performed by other allied health practitioners. The role of the advanced practitioner is to lead, participate in, and monitor the provision of high-quality care to optimise patient outcomes. Each advanced practitioner will deliver additional/enhanced interventions depending on their expertise and scope of practice and reflecting the needs of the service/patients. This may include, for example, carrying out diagnosis through advanced patient assessment, initiation of treatment plans, initiation of tests and investigations, and prescribing treatment including medication.

The fundamental role of advanced practitioners, however, is coordination. The sharing of care between orthopaedic, geriatric, and other medical specialties, such as anaesthetists, endocrinology, and rehabilitation physicians, can become fragmented and less effective if the care pathway is not coordinated effectively. Nurses in advanced practice roles are well placed to facilitate liaison between medical specialties as well as patients, their families or carers, and other services. Their focus needs to be on monitoring care, ensuring high standards of evidence-based care, while facilitating interdisciplinary team working throughout the continuum of care from fracture to rehabilitation to discharge and successful secondary fracture prevention.

The centrality of communication and coordination is also reflected in secondary fracture prevention roles such as Fracture Liaison Coordinators where the clinical coordinator case-finds patients who have had a fragility fracture, initiates treatment plans (either independently or through the family physician/GP/osteoporosis specialist) and, crucially, communicates with patients and their families and carers, monitoring treatment outcomes and concordance. The value of this role in fracture prevention has been frequently discussed in this book and we hope that this may inspire more practitioners to instigate and engage in local discussions about the development of new services across the globe as encouraged by the IOF ‘Capture the Fracture’ programme (https://www.capturethefracture.org/).

The true value of advanced practice roles in orthogeriatric and fragility fracture care is starting to be evaluated and the results so far demonstrate positive outcomes in terms of cost, length of hospital stay, and functional outcomes [13]. Optimal management and prevention of fragility fractures for a global population that will continue to age dramatically is essential. It is not an option to accept provision of sub-optimal care even when resources are limited. Because nurses are the largest and most adaptable workforce, their role needs to develop to support the ever-increasing demand for care. In countries where advanced practice roles are established, this is a valuable career progression option that keeps the best nurses clinically focused on direct patient care while taking advantage of the skills of advanced practitioners. In many countries, however, nurses are not currently empowered to develop and extend their roles so they need to be supported by other members of the interdisciplinary team in positions of greater power, such as surgeons and physicians, in developing opportunities to extend their clinical skills and education.

18.5 Chronic Condition Management

As the earlier chapters of this book have demonstrated, fragility fractures are linked with chronic health problems; not just osteoporosis, but the many comorbidities that affect older adults including frailty and sarcopenia, and concomitant chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Consequently, all members of the interdisciplinary team need skills in chronic disease management.

Most fragility fractures occur as a result of low energy trauma in the presence of osteoporosis, and it is the occurrence of the first fragility fracture that leads to a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Unfortunately, there are still far too few people around the world who are screened for fracture risk, investigated for osteoporosis, and started on appropriate treatment. This is known as the ‘treatment gap’, and this is a global problem that is as much the responsibility of the nursing community as it is the rest of the interdisciplinary team. The treatment gap (percentage of eligible individuals not receiving treatment with osteoporosis drugs) in a group of European countries is estimated to be 73% for women and 63% for men; an increase of 17% since 2010 [14].

Initial treatment and investigation to prevent further fracture most often occurs in secondary care, through coordinated structured programmes such as fracture liaison services. In these services, nurses take an active role that includes coordinating the service, making sure that vigorous and proactive case finding is implemented, and treatment and education are provided. A cost analysis showed that, when case finding and treatment are initiated and monitored as part of an FLS, the impact is not only fracture reduction, but cost saving [15].

Osteoporosis is a chronic disease that involves treatment over the remainder of the individual’s life. Understanding and adjusting to this knowledge can be difficult for individuals and their families, especially as the problem is not visible externally until a fracture happens. A diagnosis of osteoporosis and adherence with treatment needs continuing support. Nurses are experts in supporting patients, so it makes sense that they are best placed to do this, proving they have the knowledge and skills needed to do this effectively. Nurses working within FLS teams have a unique opportunity, as they are likely to be involved with the patient following a fragility fracture over a long period of time, often several years. Their role as health educators is critical to the success of medicines management and concordance alongside health promotion and health improvement. The success of nurses in these roles relates to their ability to educate the patient and their families and to promote behavioural change that improves bone health and prevents fractures. These skills are also relevant to supporting patients in managing other chronic conditions that relate to their overall health and well-being, reducing the risk of falls and associated injuries as well as improving outcomes following fractures.

18.6 Dignity and Compassion in Care

Much of this book has been focused on providing nurses and allied health professionals with the knowledge and skills to provide evidence-based physical and psychological care. But providing compassionate care is about much more than simply doing what the evidence says is best. Very few people following fragility fracture are cared for in specialist orthogeriatric units by an interdisciplinary team with expertise in both orthopaedic and older adult care. As leaders in providing compassionate, dignified care, nurses must foster an environment and culture that reflects the needs of older adults with acute care needs, ensuring that the core values of compassion, empathy, dignity, and respect are an integral part of the care provided and are not an afterthought. Providing compassionate, respectful care is a whole-system attitude and, although much has been achieved over the last few decades, there are still ageist attitudes prevalent in many healthcare systems. This has been widely demonstrated in the Covid pandemic, when many countries had policies in relation to hospital admission or treatment plans for people based upon their age, not their individual health status, most often as a means to ration access to care [16, 17].

The care provided for patients with fragility fractures in every setting needs to represent best practice, but also needs to be patient centred. Kindness, respect, and dignity mean different things to different people. Among other factors, patient-centred care requires practise to be collaborative, coordinated, and accessible. The right care being provided at the right time and the right place as well as focused on physical comfort and emotional well-being [18]. Patient and family preferences, values, cultural traditions, and socioeconomic conditions need to be considered and involvement of patients and their carers in care planning and decision-making is integral.

18.7 Evidence-Based Orthogeriatric and Fragility Fracture Nursing

There is a vast and continuously expanding body of research and evidence that directs orthogeriatric and fragility fracture care. A search of the literature will reveal that many aspects of fragility fracture care have been researched from the perspectives of acute care and rehabilitation, secondary fracture prevention, and policy [19]. Most of this research has been led by clinical researchers who are surgeons, physicians, rehabilitation specialists, and other allied health professionals. However, even though the largest proportion of fragility fracture practitioners are nurses, only a fraction of this research has been conducted or led by nurses. This is problematic; nursing care has significant potential to optimise patient outcomes following fragility fracture, as has been repeatedly identified in this book. But, unless nursing care has a specific and broad body of evidence that identifies exactly what its actions are and what its value is, its influence will be limited. This, unfortunately, restricts the ability of nursing members of the interdisciplinary team to influence the resources allocated to nursing and, consequently, prevents them from providing optimum care.

A global strategy is, therefore, needed that drives the development, conduct, translation, and application of nursing research for the care of patients with fragility fractures so that the benefits of nursing approaches can be explored and promoted alongside those of the rest of the interdisciplinary team.

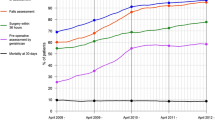

In many countries, it is now unmistakable that evidence is being applied to clinical care, as shown by audit, especially for patients with hip fractures for whom some aspects of care have improved over the last few decades [20]. Even so, much of the data collected in hip fracture audits is focused on aspects of clinical management and care that do not specifically identify the impact of effective, evidence-based nursing care on outcomes.

This is not to say that nurses should conduct research in isolation. It is important that the agenda for future research is led by priorities that reflect the needs of patients with fragility fractures as well as all members of the interdisciplinary team who provide their care. The research priorities for orthogeriatrics and fragility fracture practice need to be based on an understanding of the shared interests and concerns of patients, their families, communities, and healthcare professionals [21]. Fernandez et al. [21] conducted a study in the UK to identify key research priorities by involving multiple stakeholders including patients, family and friends, carers, and healthcare professionals. A summary of the key priorities is listed in Box 18.2:

Box 18.2 A Summary of UK Research Priorities in Fragility Fractures of the Lower Limb and Pelvis [21]

-

1.

Physiotherapy/occupational therapy in hospital and following discharge.

-

2.

Thromboembolism prevention.

-

3.

Information for patients and carers.

-

4.

Mobilisation and weight-bearing following fractures.

-

5.

Priorities for patients.

-

6.

Prevention and management of delirium.

-

7.

Pain management.

-

8.

Rehabilitation pathway for adults with dementia/cognitive impairment.

-

9.

Preventing surgical site infection.

Although the priorities summarised in Box 18.1 are specific to the country in which the research was conducted, the research questions identified are likely to be relevant in many other places and the study provides an example of good practice in relation to interdisciplinary collaboration in the research agenda. Even so, there is limited focus on nursing-specific priorities. If care is interdisciplinary, then research also be interdisciplinary. Interdisciplinary research in orthogeriatrics and fragility fracture care must involve all members of the team at the outset, including patient and care involvement. Nurse leaders may need to support nurses who possess research skills to seek to be more involved in this agenda so that they can be more certain that their role is represented.

Mixed methods studies are increasingly common and are an ideal opportunity for nurses to influence research since mixed methods approaches are more flexible in answering multifaceted questions about clinical care, and this provides an opportunity for nurses to ensure studies involve nursing care issues, especially of care activities that are nursing specific and can impact significantly on outcomes. Mixed methods studies also have the potential to foster interdisciplinary collaboration in the clinical research agenda as well as in practice.

18.8 Orthogeriatric and Fragility Fracture Nursing Education

The purpose of health professional education is to foster excellence in practice through supporting practitioners in developing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to make clinical decisions based on the best available evidence [22]. Education is the foundation of transforming care and services so that patient outcomes following fragility fracture can be optimised and future fractures prevented. The success of the Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) Call to Action (CtA) [23] is partially, but significantly, dependent on educating all health professionals involved in the management, care, and prevention of fragility fractures. Any approach to education will also need to accommodate geographical, political, and cultural differences to facilitate successful learning. The need for education is universal, crossing geographical, cultural, and professional boundaries. Global organisations such as the Fragility Fracture Network (https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/), and International Osteoporosis Foundation (https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/) as well as regional networks such as the Asia Pacific Fragility Fracture Alliance (https://apfracturealliance.org/) are bringing together face-to-face and virtual networks of practitioners, experts, leaders, and researchers from all parts of the globe. These networks, and the existence of many options for communication and sharing of knowledge and best practice examples, offer significant potential for interprofessional, professional community-led education.

The education needs of nurses and other health professionals vary depending on their existing knowledge and skills, the level of their practice, and their global location. Health professional education varies significantly from one country to another—often in tandem with how empowered nurses, for example, are to develop their practice and take control over their own professional education. Even in higher income countries, nurses do not usually receive pre-qualifying or post-qualifying education to prepare them to provide care to patients with fragility fractures—creating a gap between their knowledge and skills and patient needs. Just as the need for improvements in the care of patients with fragility fractures is global, so the need for nursing education to facilitate such improvements is an international challenge. The nursing community needs to develop a strategic plan for the leadership, planning, and delivery of education for optimum nursing and interdisciplinary care of patients with fragility fractures. This book, perhaps, can be viewed as a blueprint for a global plan for orthogeriatric and fragility fracture nursing education. Even so, education is much more than dissemination of the written words in a book, and it will take planning and effort to integrate knowledge into practice across the globe.

Even though nursing education is paramount in achieving optimum patient care, acknowledging that orthogeriatric and fragility fracture care is, by necessity, interdisciplinary is essential. The benefits of multidisciplinary approaches to care, supported by interdisciplinary education are well documented [24].

The task of facilitating learning of individuals and teams of fragility fracture practitioners at a global level requires careful consideration of how learning might be delivered in a manner that accommodates different cultures, learning needs and styles, and available resources. The mode of delivery is an important consideration. Face-to-face delivery of education is now a luxury in a world where online education is increasingly valued. It is wise, therefore, for global, regional, country, and local fragility fracture education strategies to be based on the online approach where and when possible. Ultimately, a blended approach (where online and face-to-face delivery are mixed) would be preferable, but the costs and logistic issues need to be carefully considered.

Any education programme must have a clear and workable strategy for evaluation. This needs to be much more than simply focused on learner written feedback but needs to focus on the impact of the learning on each clinician’s skills as well as the ultimate purpose of delivering optimum care as well as consideration of how this reflects the patient/carer/family perspective and how it can include the patients’ experience of their condition. Such a strategy would need consideration of different cultural aspects globally.

18.9 Conclusion

This concluding chapter has explored some of the considerations for the future of orthogeriatric and fragility fracture care from the perspective of nurses and other practitioners. The demand for care in some parts of the world will continue to escalate in the coming decades. This means that the right resources and skills need to be in place for fracture prevention to ameliorate as much of the rise in incidence as possible, and for post-fracture care to be optimised. Without such a focus, services will be overwhelmed. Orthogeriatric and Fragility Fracture Care teams need to work collaboratively with leaders and policy makers to ensure the best evidence-based care can be implemented.

The agenda that supports this important goal includes attention to workforce resources as well as the development of the roles of practitioners with particular attention to the skills needed to care for older people following acute injury as well as in health improvement and prevention of future fractures. Significant effort is also needed in the research agenda that can support future optimum practice and education of the workforce to provide this optimised care that is compassionate and person centred.

Summary of Main Points for Learning

-

The role of nurses and other practitioners in orthogeriatric care and fragility fracture management and care (definitions are provided in Chap. 1) is broad and complex.

-

The rising incidence of fractures, particularly fragility fractures, is a global public health issue placing unprecedented pressure on service.

-

Care of patients with fragility fractures is best provided practitioners who recognise the specific and complex needs of frail older people with multiple comorbidities.

-

In some places care is enhanced by nurses working in advanced practice roles that encompass advanced/specialist clinical practice, leadership, and education.

-

All members of the interdisciplinary team need skills in chronic disease management.

-

Care provided for patients with fragility fractures needs to be compassionate and patient centred.

-

Interdisciplinary research in orthogeriatrics and fragility fracture care must involve all members of the team with nurses more involved in the conduct of research.

-

The task of facilitating learning of individuals and teams of fragility fracture practitioners at a global level requires careful consideration of how learning might be delivered in a manner that accommodates different cultures, learning needs and styles, and available resources.

References

GBD 2019 Fracture Collaborators (2021) Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev 2(9):e580–e592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00172-0

IOF (2023) Epidemiology of Osteoporosis International Osteoporosis Foundation. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/facts-statistics/epidemiology-of-osteoporosis-and-fragility-fractures Accessed 26 Mar 2023

Veronese N, Kolk H, Maggi S (2021) Epidemiology of fragility fractures and social impact. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D (eds) Orthogeriatrics. Practical issues in geriatrics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48126-1_2

Dyer SM et al (2021) Rehabilitation following hip fracture. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D (eds) Orthogeriatrics. Practical issues in geriatrics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48126-1_12

Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) (2023) Fragility Fracture Network Values https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/. Accessed 26 Mar 2023

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) The state of the world’s nursing 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279. Accessed 27 Mar 2023

World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) Health workforce https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce#tab=tab_1. Accessed 27 Mar 2023

Fitzgerald A, Verrall C, Henderson J, Willis E (2020) Factors influencing missed nursing care for older people following fragility hip fracture. Collegian 27(4):450–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2019.12.003

Aiken L et al (2014) Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 383(993):1824–1830

Henderson V (2006) The concept of nursing. 1977. J Adv Nurs 53(1):21–31; discussion 32–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03660.x

Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D (2021) Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 77(8):3286–3302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14839

MacDonald V, Maher AB, Mainz H, Meehan AJ, Brent L, Hommel A, Hertz K, Taylor A, Sheehan KJ (2018) Developing and testing an international audit of nursing quality indicators for older adults with fragility hip fracture. Orthop Nurs 37(2):115–121. https://doi.org/10.1097/NOR.0000000000000431

Allsop S, Morphet J, Lee S, Cook O (2021) Exploring the roles of advanced practice nurses in the care of patients following fragility hip fracture: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 77(5):2166–2184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14692

Borgström F, Karlsson L, Ortsäter G, Norton N, Halbout P, Cooper C, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Kanis JA (2020) International osteoporosis foundation. Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos 15(1):59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-0706-y

McLellan AR, Wolowacz SE, Zimovetz EA et al (2011) Fracture liaison services for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture: a cost-effectiveness evaluation based on data collected over 8 years of service provision. Osteoporos Int 22:2083–2098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1534-0

Fraser S et al (2020) Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society’s response say about us? Age Ageing 49(5):692–695. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa097

Lytle A, Levy SR (2022) Reducing ageism toward older adults and highlighting older adults as contributors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Soc Issues 78:1066–1084. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12545

Anon (2017) What is patient centred care? NEJM Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559. Accessed 28 Mar 2023

Marsh D et al (2021) The multidisciplinary approach to fragility fractures around the world: an overview. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D (eds) Orthogeriatrics. Practical issues in geriatrics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48126-1_1

Johansen A, Boulton C, Hertz K, Ellis M, Burgon V, Rai S, Wakeman R (2017) The National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD)—Using a national clinical audit to raise standards of nursing care. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 26:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijotn.2017.01.001

Fernandez MA, Arnel L, Gould J et al (2018) Research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open 2018(8):e023301. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023301

Lehane E et al (2019) Evidence-based practice education for healthcare professions: an expert view. BMJ Evid Based Med 24(3):103–108

Dreinhöfer KE, Mitchell PJ, Bégué T et al (2018) A global call to action to improve the care of people with fragility fractures. Injury 49(8):1393–1397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.06.032

Santy-Tomlinson J, Laur CV, Ray S (2021) Delivering interprofessional education to embed interdisciplinary collaboration in effective nutritional care. In: Geirsdóttir ÓG, Bell JJ (eds) Interdisciplinary nutritional management and care for older adults. Perspectives in nursing management and care for older adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63892-4_12

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hertz, K., Santy-Tomlinson, J. (2024). Orthogeriatric and Fragility Fracture Care in the Future. In: Hertz, K., Santy-Tomlinson, J. (eds) Fragility Fracture and Orthogeriatric Nursing . Perspectives in Nursing Management and Care for Older Adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33484-9_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33484-9_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33483-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33484-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)