Abstract

Nutrition and hydration are fundamental aspects of healthcare, especially in the care of older people, particularly those in hospitals or in long-term care facilities. Worldwide, nurses are ‘best-placed’ coordinators of interdisciplinary nutritional management and care processes. Even so, it is essential that nurses collaborate with other healthcare specialists as an interdisciplinary team to provide high-quality care that reflects patients’ needs for assessment, intervention, and health promotion. When an interdisciplinary team work collaboratively, care is more successful, improves patient outcomes, and reduces the risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality.

The care process begins with screening and monitoring of the nutritional status and fluid intake of all older people within 24 h of admission. In the case of positive screening, comprehensive assessment and involvement of other team members should undertake to understand the underlying problem. Appropriate food and appealing meals, snacks, and drinks should be available and offered with recommended amounts of energy, protein, vitamins, minerals (particularly calcium), and water. This should be complemented with supplementary drinks if intake is not adequate. The prescription of vitamin D and calcium should be discussed.

Patient-centred and evidence-based information should provide and interventions in the case of end-of-life care should be appropriate discussed. Educating, informing, and involving patients and families increases their level of health literacy. Malnutrition and/or dehydration management should be included in the discharge plan.

The aim of this chapter is to increase awareness of nurses’ responsibility, within a multidisciplinary team, for assessment and intervention of nutrition and hydration, examine the issues pertaining to nutrition and fluid balance in older people and outline the nature, assessment and interventions relating to malnutrition and dehydration.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

11.1 Introduction

At the ESPEN congress in Vienna 2022, an international declaration to recognise nutritional care as a human right was agreed [1, 2]. Especially in the care of older people, particularly those in hospitals or in long-term care facilities, nutrition and hydration are a fundamental aspect of care. Many older people do not eat and drink adequately during hospital stays and, following hip fracture, many patients achieve only a half of their recommended daily energy, protein, and other nutritional requirements [3, 4]. This leads to poor recovery, diminished health status and physical and functional ability, mortality, and a higher risk of other complications. Optimal nutrition and hydration are central to preventing and managing falls, osteoporosis, fragility fractures, chronic and acute health conditions, and frailty as well as recovery and rehabilitation following injury, fractures, and surgery. If nutritional care is optimised, all other aspects of care are likely to result in better outcomes.

Across global settings, nurses are ‘best-placed’ coordinators of interdisciplinary nutritional management and care. It is essential, however, that nurses bring other healthcare specialists together as a team to collaboratively provide high-quality care that reflects patients’ needs for assessment, intervention, and health promotion. When an interdisciplinary team (orthogeriatric collaboration) work together care is more successful, improves patient outcomes, and reduces the risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality.

The aim of this chapter is to increase awareness of nurses’ responsibilities, within a multidisciplinary team, for assessment and intervention for nutrition and hydration, examine the issues pertaining to nutrition and fluid balance in older people and outline the nature, assessment, and interventions relating to malnutrition and dehydration.

11.2 Learning Outcomes

At the end of the chapter, and following further study, the practitioner will be able to:

-

Identify those at risk of malnutrition and dehydration.

-

Prevent complications of poor nutrition and dehydration through effective intervention and health promotion.

-

Identify the nurse’s role in coordination of the interdisciplinary team to best meet patients’ needs.

Box 11.1:Malnutrition in Older People: A Case Example

Michael is a 78 year-old wine maker living at home with his wife. Fit and healthy in his younger years, Michael gained a lot of weight after he handed over the vineyard to his son. This was most likely from a combination of reduced physical activity, more regular visits to the local marketplace to purchase baked goods as a substitute for smoking, and his longstanding love of beer as well as wine. Michael now tends to avoid eating meat and his favourite fresh fruits due to poor dentition. In his early 70s, he was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Type II diabetes. He is weight stable with a BMI of 37. More recently, his wife had been making some jokes about his very thin ‘chicken’ legs and expanding waistline. It was these same thin legs that could not balance his weight when he slipped on a wet pavement on his way to the market and fell, breaking his hip.

Consider:

Michael is a typical example of people with health problems in middle- and high-income countries. Patients in low-income countries may have nutritional issues depending on local culture and social conditions. Therefore, caregivers must be aware that health problems are often influenced by social and financial factors, but that having a higher income does not necessarily mean that malnutrition is less likely.

11.3 A Healthy Diet for Older Adults

As individuals and populations age, what people eat changes in response to lifestyle, appetite, and health-related factors. Regardless of age, in developed countries, people are now consuming more food high in energy, fats, sugars, and salt than in previous decades. While undernutrition leads to a higher risk for health-related problems, obesity also contributes to increased morbidity and mortality from diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.

A key factor for healthy aging is the selection and preparation of healthy food. This can support the prevention of malnutrition in every form. When considering what is ‘healthy’, it is important to consider an individual’s intake, uptake, and requirements for nutrients. For the case example in Box 11.1 above, an age-related change in appetite combined with dentition problems negatively influenced the intake of protein, essential vitamins, minerals, and fibre. This was further compounded by malabsorption associated with poorly controlled diabetes, and the increased requirements of chronic lung disease, resulting a dual diagnosis of undernutrition and obesity. A careful assessment would identify that Michael has a dual diagnosis of undernutrition and obesity, resulting from high fat and sugar intake, inadequate protein intake, increased nutritional requirements of disease, and reduced uptake of nutrients associated with poorly controlled diabetes [5].

It is essential that healthcare professionals identify the determinants of malnutrition, whether related to deficiencies or excesses in nutrient intake, imbalance of essential nutrients, or impaired nutrient utilisation [6]. Campaigns have been launched in previous years in Europe, the USA, and other countries [7,8,9,10], for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) global initiative on the Implementation of Nutrition Action [11]. All these campaigns have had the goal to increase the awareness that nutritional care as a human right is fundamental to improving the quality of care for patients across different settings and stages of life [1, 2].

It is important to focus on the different levels of action that may be taken:

11.3.1 Actioning a ‘Healthy’ Diet that Is Relevant to Age and Stage

Increasing age, physiological, psychological, and lifestyle changes increase the incidence of chronic diseases, fractures, and disabilities. This is not only a result of changing metabolism or physical circumstances, but also due to lack of knowledge regarding appropriate strategies to prevent and manage malnutrition. This may require a shift in approach regarding what is ‘healthy’ over time. For example, a low saturated fat, high fibre, energy-deficient diet may have been helpful to promote healthy weight loss for Michael in his 60s; however, optimising nutrition intake towards a nutrition-rich diet should be considered a higher priority with his inadequate protein and micronutrient intake, malnutrition, and recent hip fracture [12].

While the requirement for some nutrients (e.g. carbohydrates and fats) decreases with older age, the requirement for protein, vitamins, and minerals remains stable or increases for protein and vitamin D [13, 14]. Most fragility fracture patients, like Michael, are over the age of 60 years when admitted to hospital where it is essential that patients receive a diet with an appropriate amount of energy, and which is rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals. In the case of suspected weight loss, acute disease or increased requirements to support recovery from fractures and surgery, a diet higher in energy is also often necessary. Moving into rehabilitation and recovery phases, dietary changes should be adapted to the needs of the patient, for example, to decrease the risk of falls, fractures, and osteoporosis, support recovery and healing, and manage comorbidities.

11.3.2 Healthy Nutritional Guidelines for Healthy Older Adults

At the individual level, practitioners should have knowledge about healthy diets for every age group. A rudimentary approach to intake and distribution of macronutrients (carbohydrates, fat, and proteins) considers the following recommendation as an orientation for healthy adults [15]:

Carbohydrates | Fats | Proteins |

|---|---|---|

45–65% | 20–35% | 10–35% |

However, the requirement for macronutrients and micronutrients should be adjusted depending on the individual condition of the patient. According to the WHO recommendations, a healthy diet for healthy adults contains the following key aspects [16]:

-

Eat at least 400 g (5 portions) of fruits and vegetables per day.

-

Eat less than 10% of total energy intake from free sugars (equivalent to 50 g for a person of healthy body weight consuming approximately 2000 calories per day).

-

Eat less than 5 g of salt per day, and preferably iodised salt.

-

Eating unsaturated fats (e.g. from fish, avocado, nuts, olive oil) is preferable to saturated fats (e.g. in fatty meat, butter, palm, and coconut oil).

11.3.3 Energy, Protein, and Fluid Requirements

Although the calculation of energy intake for older people varies between countries, it often includes two steps:

-

(a)

Calculation of baseline energy needs, which depends on age, gender, and general health aspects.

-

(b)

The physical activity level (PAL) of the person. The PAL in older adults in hospitals is estimated to be between 1.2 and 1.4.

An estimate of recommended baseline energy intake for older people is 30 kcal/kg/bodyweight per day. These minimum requirements are increased for those who are malnourished or with raised requirements associated with increased metabolic requirements or malabsorption. The minimum recommended intake of protein per day is at least 1g/kg/ bodyweight [17]. So, an older person with a bodyweight of 70 kg needs an energy intake of about 2100 kcal and 70 g protein per day. Older people, especially those recovering from fracture and surgery, have fluctuating metabolic needs and practitioners must ensure that sufficient energy and other nutrients are available for recovery and wound healing. Where differences in individual requirements are likely, or if patients need more detail nutritional support, other members of the interdisciplinary team should be involved, such as dieticians. Nurses are often responsible for coordinating the multidisciplinary team in deciding the appropriate amount of energy and protein intake based on the specific condition of each patient. Complex patients like Michael (see Box 11.1) will need additional professional support from a dietician or dietetics expert.

The recommended daily fluid intake for people over the age of 65 years is 2250 mL. This consists of approximately 60% direct fluid (from drinking) and 40% indirect fluid (from food and oxidation) [18]. In the case of kidney or heart disease or other health problems that necessitate restriction of fluid intake, a physician should be involved in estimation of the appropriate amount of daily fluid required. Practitioners must use this baseline information to educate patients and carers about healthy eating and fluid intake.

11.4 Calcium and Vitamin D

Two crucial factors in bone health are calcium and vitamin D; vitamin D is essential for the uptake and absorption of calcium. The daily amount of calcium intake required for people over 65 years depends on country-specific recommendations but should be a minimum 1000 mg [20, 21]. Table 11.1 shows the main sources of calcium with minimum amounts of 250 mg and 100 mg calcium. Other good sources of calcium are milk, salmon, and tofu [21]. If a patient is not able to meet the needs for calcium from their food, they should be prescribed calcium supplements.

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that is vital for calcium uptake to bone, especially important in later life. Food contains only a small amount of vitamin D; the main source is sunlight. The production of vitamin D (specifically vitamin D3) takes place in the skin under the influence of ultraviolet (UV-B) light. The production of vitamin D is limited where sunshine is depleted, such as in northern Europe and northern North America, particularly during wintertime. The capacity to produce vitamin D decreases in older age by four times, resulting in lower levels [22]. To achieve the recommended amount of Vitamin D it is advised that the hands, arms, and face should be exposed to sunlight for approximately 5–25 min per day [23]. At the same time, age, geographic latitude, air pollution, and other factors influence the appropriate production of Vitamin D in the skin. The blood level of Vitamin D should be checked regularly and, if necessary, supplemented as part of a comprehensive therapy plan. The recommendation for adequate supplementation of vitamin D intake for older people is 800–1000 IU per day [24]. With the reduction of the risk of hip fracture and other fractures in mind, older patients benefit from a combination of Vitamin D and calcium if the level of Vitamin D is low and the intake of calcium is poor [25, 26].

Although nutrition is important in preventing fragility fractures, it is also essential for maintaining the positive effects of weight-bearing activity and exercise training on bone density [27]. Regular physical activity of 30 min per day promotes calcium resorption and supports muscle growth and bone density [28]. Following hip fracture, patients should be encouraged to participate in daily activity as part of their discharge plan, supported by inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation programmes. If patients are independent in activities of daily living and do not suffer from other health problems or disabilities which limit physical activity, additional information about specific exercises and activities should also be provided (see Chap. 8).

11.5 Definitions of Malnutrition and Dehydration

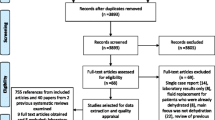

To identify and treat patients with malnutrition or dehydration, practitioners need to know how malnutrition and dehydration are defined. According to NANDA [29], malnutrition is: ‘Intake of nutrients insufficient to meet metabolic needs’. A recent consensus-based definition for the diagnosis of malnutrition (GLIM) comes from the global initiative of clinical nutrition societies [30]. The group defined weight loss, low BMI, and reduced muscle mass as phenotypic criteria and reduced food intake or problems with assimilation and disease burden/inflammation as etiologic criteria. The definition of malnutrition contains at least one phenotypic and one etiologic criterion to be positive (see Fig. 11.1). In the final step, the severity must be measured based on phenotype criterion. The group recommended within a diagnostic process the following procedure for clinical settings:

The GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition [30]

The definition of dehydration is more complex as it can refer to both loss of body water and volume depletion following the loss of body water; it is suggested [31] that it is defined as a complex condition resulting a reduction in total body water. This can be related to both total water deficit (‘water loss dehydration’) and combined water and salt deficit (‘salt loss dehydration’) due to both too low intake and excessive/unbalanced excretion.

11.6 Prevalence, Determinants, and Symptoms of Malnutrition and Dehydration

The prevalence of malnutrition in care facilities differs widely depending on location, for example, in geriatric wards the prevalence is higher than on coronary wards [32]. The estimated number of patients admitted to acute hospitals being at risk of malnutrition is approximately 35% with 20–50% [33].

The reported prevalence of dehydration also varies and depends on which definition of dehydration and which research methods are used. It is estimated that 40% of people newly admitted to hospital are dehydrated and 42% of patients who were not dehydrated at admission were dehydrated 48 h later. Because people who live in residential institutions are often very frail, dehydration is estimated to be 46% in these settings [31].

The risk factors for malnutrition vary between clinical settings and patient groups. A theoretical framework for the aetiology of malnutrition does not exist. The European Knowledge Hub ‘Malnutrition in the Elderly (MaNuEL)’, developed a model for ‘Determinants of Malnutrition in Aged Persons’ (DoMAP) in a multistage consensus process with multiprofessional experts in geriatric nutrition (see Fig. 11.2) [34].

-

The main etiologic mechanisms are placed in the middle of the model (level one, dark green).

-

The factors in the light green triangle (level two) are the determinants which directly lead to one of the main factors, for example, as hyperactivity leads directly to high requirements.

-

The third level (yellow) contains determinants which indirectly lead to one or more central mechanisms through factors in level two. For example, a side effect of medication may lead to poor appetite and to a lower intake.

-

Around the pyramid are typical age-related factors, which additionally influence the process of malnutrition. Some factors, such as hospitalisation or polypharmacy, might be starting points for developing malnutrition.

Determinants of Malnutrition in Aged Persons (DoMAP) [34] (reproduced with permission)

Other factors like frailty or multimorbidity may progressively worsen the nutritional status of older adults. The symptoms of malnutrition vary and may manifest as weight loss, low energy levels, lethargy, low mood, depression, cognitive decline [35], delayed wound healing, diarrhoea, limited/reduced muscle tone (sarcopenia), and/or lack of interest in, or aversion to, eating/drinking [36].

The signs of dehydration are seen earlier than malnutrition; common symptoms include increasing heart rate, diminished urine output, nausea, dry lips, spasm, unexplained mental confusion [37] and, sometimes, pale mucosa [38].

11.7 Screening and Assessing for Malnutrition

Screening and assessment for malnutrition should be conducted with a validated instrument. Examples of validated instruments are [39, 40]:

-

3-min nutrition screening (3MinNS).

-

Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002).

-

Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA).

-

Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST).

-

Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST—cut off >2).

-

Unwanted weight loss (more than 5% in the last 3 months).

The selection of an appropriate and validated screening instrument should be made according to the clinical setting and with common underlying health issues in mind. Multidisciplinary teams should also be collaboratively involved in the decision and implementation process to increase the rate of acceptance and use of the selected instruments.

The implementation of screening and assessment should lead to a structured process of identification of those at risk of malnutrition. The process should follow two steps:

1. Screen everyone within 24 h of admission to identify those at risk or with the diagnosis of malnutrition.

2. Assess all those identified as at risk to provide a comprehensive understanding of the problem to enable planning of appropriate interventions.

If a patient is at risk of malnutrition, or already malnourished, the information obtained from screening and assessment should be used to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the individual issues as part of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) process (see Chap. 6) to facilitate an individualised plan for avoiding or treating malnutrition.

Regarding Michael’s situation, the following steps should be undertaken (see case study Box 11.1):

-

Involvement of his wife and other carers to understand and assess his nutritional status and needs.

-

Collaboration with members of the interdisciplinary team such as dieticians, physicians, dentists, or physiotherapist.

-

Discuss with Michael, his wife and other carers about nutritional-related goals and development of an individualised intervention plan.

-

Set a follow-up appointment to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention plan

-

Other general actions may include:

-

In case of end-of-life care, the application of artificial nutrition should be discussed in respect to the principles of bioethics including beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice with full consultation the patient, his relatives, and the interdisciplinary team (Chap. 17)

-

Ensure continuity of nutritional care throughout hospital, rehabilitation, and home care.

11.8 Evidence-Based Interventions to Prevent and to Treat Malnutrition

Malnutrition, or risk of malnutrition, should be approached as a multifactorial problem. It is important that interventions to prevent malnutrition begins with recording a nutrition history and monitoring the patient’s food intake during the first days after admission. The ESPEN guideline for clinical nutrition and hydration in older persons provides evidence-based recommendations for preventing and/or treating malnutrition and dehydration [17]. The treatment of malnutrition involves several specific aspects:

11.8.1 Arrangements for Food and Meals

-

Meals in hospitals and, particularly, in long-term care facilities, are often tasteless. To improve the taste, practitioners should liaise with those responsible for the cooking of meals.

-

Changes in the nature and variety of food or the use of flavoursome sauces are simple and cheap ways to improve taste.

-

As well as the usual timed meals, snacks should be offered by staff or, as self-service, made easily accessible for patients over 24 h. Food should reflect the patient’s preferences.

-

For those with physical or psychological difficulties with eating, assistance should be provided with the use of appropriate aids (e.g. large handles on cutlery, coloured glasses for visually impaired patients) to help increase independence.

-

Where there are specific problems such as difficulty swallowing or poor dentition, other professionals should be involved as physicians, speech therapists, and dentists to address the problem [41].

11.8.2 Dietary Supplementation

-

Patients with difficulties eating adequate amounts of food should be offered multi-nutrition supplements with at least 400 kcal/day including 30 g or more of protein/day [17].

-

Dietary supplements (enteral nutrition) are liquid foods that are used to improve nutritional intake [42]. This is particularly important in frail older people in the perioperative period as there is evidence that dietary supplements, especially for older patients with hip fractures, have a positive effect on quality of life and help to reduce complications [17, 43, 44].

-

To support muscle strength gain during recovery and rehabilitation, high-protein supplements should be combined with muscle resistance training exercise with the physiotherapy team (Chap. 8)).

-

Patients should be informed about the reason for supplementation and be asked about their preferences in the taste or temperature of the supplement.

-

If patients have intolerances or problems eating and drinking because of the taste, a dietician should be involved.

-

Physicians should be reminded of the need for vitamin D supplementation.

-

Providing information material about healthy diet and fluid intake in older age, particularly about the requirement for minerals and vitamin D, is essential during discharge management.

11.8.3 Interaction during Mealtimes

-

Patients are often highly dependent on the help of nurses and other care givers, especially those with cognitive or functional decline who are already at risk of malnutrition. Practitioners must, therefore, consider individual needs for support with eating.

-

Creating a culture in which mealtimes are periods of calm with as few interruptions as possible can increase the likelihood of adequate intake [45]. It is also important that enough help is available at mealtimes to support eating and that families are encouraged to be involved.

11.8.4 Environmental and Personal Requirements

-

The environment in hospitals and residential facilities can be unfamiliar and impersonal. Mealtimes are important human interaction opportunities normally conducted in pleasant, comfortable surroundings conducive to appetite.

-

Nurses and other practitioners should involve support workers, volunteers, and families in creating a pleasant environment for eating, considering issues such as adequate table decoration adapted to the seasons to help patients to be more orientated, feel more comfortable, and increase the likelihood of them eating adequately [46].

11.8.5 Education, Support, and Guidance

-

Patients and families can be unaware of the risk of malnutrition, malnutritional diagnosis, and the consequences of malnutrition.

-

Education, information, support, and guidance are important in engaging patients and carers in eating well. Information needs to be individualised and can be provided in a variety of ways. Some people prefer written information (e.g. leaflets, visual aids, or posters), while others prefer technological approaches such as apps on smartphones and/or Internet-based information.

-

A good source for evidence-based information are the websites of the country-specific nutritional societies (e.g. nutrition care in accreditation or clinical care standards/comprehensive care standards) [47].

11.8.6 Medication Review

-

The medical doctor should regularly check the medical management of conditions adversely influence nutrition, for example, nausea, vomiting (see Chap. 6, CGA).

11.8.7 Quality Management

-

Hospitals, and specific units where care is provided to older people, should review their structures and processes of nutrition management in order to identify neglected aspects.

-

The implementation of high-quality nutritional management in a hospital should be based on well-evaluated nutritional programs [48].

-

The process of implementation and evaluation of the nutritional program can be supported by a hospital wide quality improvement system along the PDCA process (‘Plan, Do, Check, Act’).

11.9 Hydration and Dehydration

Dehydration is common among hospitalised older adults with significant adverse consequences. The screening of those at risk of dehydration is challenging because of the unspecific symptoms and how rapidly it develops. Box 11.2 lists the main risk factors for dehydration.

11.9.1 Screening and Assessing Patients with Dehydration

To identify people at risk of dehydration, practitioners should follow the same procedure as for the risk of malnutrition. However, unlike malnutrition, there are no validated screening tools, so nurses need to use their knowledge and skills to make individualised assessments by:

-

1.

Screening all patients within 24 h of admission to identify risk factors for dehydration.

-

2.

Assessing all patients at risk to enable a comprehensive understanding of the problem and plan appropriate measures.

Box 11.2: Risk Factors for Dehydration

-

Low BMI

-

Depleted thirst

-

Dependent on care

-

Cognitive impairment

-

Frailty and comorbidities

-

Neurological deficits such as hemi- and paraplegia

-

Dysphagia

-

Constipation, diarrhoea, vomiting, and incontinence

-

Fear of incontinence and reluctance to drink

-

Taking potassium-sparing diuretics

As well as considering the risk factors identified in Box 11.2, criteria for positive risk screening of people for dehydration may include [40]:

-

Fatigue and lethargy

-

Not drinking between meals

-

BIA (bioelectrical impedance analysis) resistance at 50 kHz (BIA assesses electrical impedance through the body commonly from the fingers to the toes and is often used to estimate body fat)

Additional screening tests with limited diagnostic accuracy include:

-

Decreasing drink intake

-

Diminished urine output

-

High urine osmolality

-

Low axilla moisture (dry armpits)

11.9.2 Assessment and Further Action

If the patient is dehydrated, or at risk of dehydration, screening should achieve a comprehensive understanding of the underlying issues and generate a care plan of appropriate measures to treat or prevent dehydration. This should include:

-

Close monitoring and recording of both fluid intake and urinary and other fluid output such as vomiting or wound drainage.

-

Ensure toileting facilities are easily accessible, and if not, or patient’s physical activity is limited, use aids such as urine bottles or commodes. Patients who have difficulty reaching the toilet are more likely to restrict their fluid intake.

-

Involvement of the patient and family/carers in the assessment and plan of care, including encouraging fluid intake of approximately 2.0 L/day for women and 2.5 L/day for men of all ages (from a combination of drinking water, beverages, and food) if not contraindicated.

-

Involvement of other members of the team such as physicians and ensuring that the whole of the nursing team, including support workers/carers, are aware of the risks and the need to closely monitor fluid intake and supplement as required.

-

Discuss with patients and their family/caregivers the risks, plan of care and aims of care in terms of volume of fluid required and engage family in supporting the aims.

-

Ensure the problem is included within the discharge plan.

11.9.3 Evidence-Based Interventions to Prevent and Treat Dehydration

Patients’ oral fluid intake is often inadequate, especially early in the patient pathway while fasting and undergoing perioperative preparation. It is essential to closely monitor and document fluid intake and output and to supplement intake, where necessary, with intravenous fluids.

Prevention aims to ensure the availability of drinks that are pleasant to drink and that patients and families understand the necessity to drink. Support and help are needed to facilitate adequate intake of oral fluids with the following advice in mind [49]:

11.9.3.1 Availability of Drinks

Drinks should be constantly and easily available. Frequent regular drinks ‘rounds’ should take place; to support nurses and other care givers, volunteers, or assistants may be given responsibility for this activity. Care giving activities can act as prompts to support patients with drinking oral fluids such as during medication rounds.

11.9.3.2 Drinking Pleasure

Taking pleasure in drinking depends on individual preferences including types of fluid, temperature, and flavour. Asking patients/families about preferences and considering factors that can support fluid intake such as reminders to drink and social interaction can be useful.

11.9.3.3 Support and Help to Drink

Offering individualised support to patients to help them to drink can encourage adequate fluid intake. This should be done in a friendly, unhurried, and calm manner using appropriate drinking aids such as straws and special cups or with bottle-clipped systems. Families often feel helpless but may be able to help with drinking so that they feel involved and useful. Family members can be offered information including how to recognise dehydration and how to help with drinking.

11.9.3.4 Monitoring and Understanding of the Necessity to Drink

Nurses and other care givers should provide appropriate information so that patients understand the benefit of adequate fluid intake. Accurately monitoring and recording intake and asking patients/families about the baseline daily fluid intake are essential. All involved the need to be aware of the outward signs of dehydration such as:

-

Diminished urine output and concentrated urine.

-

Dry lips, mucous membranes, diminished skin turgor.

-

Muscle weakness, dizziness, restlessness, headache.

Summary of Main Points for Learning

-

The care process begins with screening and monitoring of the nutritional status and fluid intake of all older people within 24 h of admission.

-

In the case of a positive screening, a comprehensive assessment and involvement of other team members should undertake to understand the underlying problem.

-

Appropriate food and appealing meals, snacks and drinks for older people should be available and offered with recommended amounts of energy, protein, vitamins, minerals (particularly calcium), and water; this should be complemented with supplementary drinks if intake is not adequate.

-

The prescription of vitamin D and calcium should be discussed with the patient’s physician.

-

Patient-centred and evidence-based information should provide and interventions in the case of end-of-life care should be appropriate discussed.

-

Educating, informing, and involving patients and families increases their level of health literacy.

-

Malnutrition and/or dehydration management should be included in the discharge plan.

11.10 Suggested Further Study

Access and read the following review paper. Make some notes about ways in which the paper’s conclusions could impact on your practice and that of your team:

-

Sauer A et al. (2016) Nurses needed: Identifying malnutrition in hospitalized older adult. Nursing Plus Open https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.05.001

Use the following open access book as a reference guide for your further study of this topic:

-

Geirsdóttir, Ó.G., Bell, J.J. (eds) Interdisciplinary Nutritional Management and Care for Older Adults. Perspectives in Nursing Management and Care for Older Adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63892-4_1

Find out what nutritional guidelines are available in your own region. Read them carefully and think about how these could be used to develop simple strategies for improving diet and fluid intake in your patients and discuss this in your team.

Undertake an audit of nutrition and fluid charts of patients who are at risk of malnutrition or dehydration. Discuss with the team, including a dietician, whether you are adequately recording intake and output. Reflect on its implications, and what you could do to improve this practice.

Develop an information leaflet for patients/families about why and how patients can make sure they get enough to eat and drink. Discuss this within the team.

Talk with patients/carers/staff about the things they feel that prevent good diet and fluid intake for patients. Reflect on what these conversations suggest about how practice might be developed to improve patient’s nutrition and hydration status.

11.11 How to Self-Assess Learning

To identify learning achieved and the need for further study, the following strategies may be helpful:

-

Examine local documentation of nursing care regarding nutrition and hydration and use this to assess your knowledge and performance.

-

Seek advice and mentorship from other expert clinicians such as dietician and seek their help to keep up to date on new evidence and disseminate to your team.

-

Peer review with colleagues can be used to assess individual progress and practice but should not be too formal.

-

Therefore, modern methods of education like training on the job or training near the job should be used. Staff are able to learn more easily within this non-formal environment new expertise in certain topics. Furthermore, these training methods support an environment in which an open discussion is possible.

-

Weekly case conferences regarding patients like Michael with nutrition or hydration problems are also good options to identify nurse-focused issues and enable the exchange of expertise. Expertise is conveyed to the various members of the multidisciplinary team by educational initiatives and by fostering a culture where all the patients’ problems are considered.

-

The implementation of a quality improvement system helps to identify neglected areas of action. The systems support the work along patient-related processes.

References

Cárdenas D, Correia MITD, Ochoa JB et al (2021) Clinical nutrition and human rights. An international position paper. Clin Nutr 40:4029–4036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.02.039

Cárdenas D, Toulson Davisson Correia MI, Hardy G et al (2022) Nutritional care is a human right: translating principles to clinical practice. Clin Nutr 41:1613–1618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.03.021

Bell J, Bauer J, Capra S et al (2013) Barriers to nutritional intake in patients with acute hip fracture: time to treat malnutrition as a disease and food as a medicine? Can J Physiol Pharmacol 91:489–495. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2012-0301

Duncan D, Murison J, Martin R et al (2001) Adequacy of oral feeding among elderly patients with hip fracture. Age Ageing 30:22

Bell JJ, Pulle RC, Lee HB et al (2021) Diagnosis of overweight or obese malnutrition spells DOOM for hip fracture patients: a prospective audit. Clin Nutr 40:1905–1910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.09.003

WHO Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_1. Accessed 06 Nov 2022

DeSilva D, Anderson-Villaluz D (2021) Nutrition as We Age: Healthy Eating with the Dietary Guidelines. https://health.gov/news/202107/nutrition-we-age-healthy-eating-dietary-guidelines

European Nutrition for Health Alliance (2021) EAN Guideline: Promoting well-nutrition in elderly care. https://european-nutritionorg/good-practices/ean-guideline-promoting-well-nutrition-in-elderly-care/. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

The European Ageing Network EAN Guideline: Promoting well-nutrition in elderly care. https://european-nutrition.org/good-practices/ean-guideline-promoting-well-nutrition-in-elderly-care/. Accessed 06 Nov 2022

ODPHP (2021) Nutrition as We Age: healthy eating with the dietary guidelines. https://health.gov/news/202107/nutrition-we-age-healthy-eating-dietary-guidelines. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

WHO (2012) Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA). https://extranetwhoint/nutrition/gina/. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

European Food Information Council (2016) New dietary strategies for heathy ageing in Europe (NU-AGE). http://www.eufic.org/en/collaboration/article/new-dietary-strategies-for-healthy-ageing-in-europe. http://www.eufic.org/en/collaboration/article/new-dietary-strategies-for-healthy-ageing-in-europe. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

Nordic Council of Ministers (2014) Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012: integrating nutrition and physical activity. Nordic Council of Ministers, s.l

Ahmed T, Haboubi N (2010) Assessment and management of nutrition in older people and its importance to health. Clin Interv Aging 5:207–216. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s9664

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020) Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Make Every Bite Count With the Dietary Guidelines. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2023

World Health Organization (2015) Healthy diet. Factsheet No 394. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs394/en/. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T et al (2019) ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr 38:10–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024

Gesellschaft für Ernährung e. V. (2017) Wasser (Water). http://www.dge.de/wissenschaft/referenzwerte/wasser/. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

Better Health Channel (2021) Calcium. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/calcium#good-sources-of-calcium. Accessed 11 Nov 2022

Warensjö E, Byberg L, Melhus H et al (2011) Dietary calcium intake and risk of fracture and osteoporosis: prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 342:d1473. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d1473

IOF (2019) Calcium: A key nutrient for strong bones at all ages. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/sites/iofbonehealth/files/2019-12/Patient_calcium-factsheet.pdf

Cashman KD, Dowling KG, Škrabáková Z et al (2016) Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: pandemic? Am J Clin Nutr 103:1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.120873

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung (2012) Ausgewählte Fragen und Antworten zu Vitamin D. https://www.dge.de/wissenschaft/faqs/vitamin-d/. Accessed 11 Nov 2022

Dachverband Osteologie e.V. (2014) Osteoporose bei Männern ab dem 60. Lebensjahr und bei postmenopausalen Frauen: Leitlinie des Dachverbands der Deutschsprachigen Wissenschaftlichen Osteologischen Gesellschaften e.V. http://www.dv-osteologie.org/uploads/Leitlinie%202014/DVO-Leitlinie%20Osteoporose%202014%20Kurzfassung%20und%20Langfassung%20Version%201a%2012%2001%202016.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

Bouillon R, Manousaki D, Rosen C et al (2022) The health effects of vitamin D supplementation: evidence from human studies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 18:96–110. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00593-z

Mulligan GB, Licata A (2010) Taking vitamin D with the largest meal improves absorption and results in higher serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res 25:928–930. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.67

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2017) Osteoporosis exercise for strong bones. https://www.nof.org/patients/fracturesfall-prevention/exercisesafe-movement/osteoporosis-exercise-for-strong-bones/

Office of the Surgeon General (US) (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the surgeon general, Rockville (MD)

NANDA International (2011) Nursing interventions for imbalanced nutrition less than body requirements. http://nanda-nursinginterventions.blogspot.co.uk/2011/05/nursing-interventions-for-imbalanced.html

Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia MITD et al (2019) GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr 38:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.002

Thomas DR, Cote TR, Lawhorne L et al (2008) Understanding clinical dehydration and its treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 9:292–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2008.03.006

Meijers JMM, Schols JMGA, van Bokhorst-de Schueren MAE et al (2009) Malnutrition prevalence in The Netherlands: results of the annual Dutch national prevalence measurement of care problems. Br J Nutr 101:417–423. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114508998317

Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC (2011) Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8:514–527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020514

Volkert D, Kiesswetter E, Cederholm T et al (2019) Development of a model on determinants of Malnutrition in aged persons: a MaNuEL project. Gerontol Geriatr Med 5:2333721419858438. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721419858438

Blondal BS, Geirsdottir OG, Halldorsson TI et al (2022) HOMEFOOD randomised trial - six-month nutrition therapy improves quality of life, self-rated health, cognitive function, and depression in older adults after hospital discharge. Clin Nutr ESPEN 48:74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2022.01.010

Nursing Times (2009) Malnutrition. https://www.nursingtimes.net/archive/malnutrition-20-05-2009/. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

El-Sharkawy AM, Sahota O, Maughan RJ et al (2014) Hydration in the older hospital patient - is it a problem? Age Ageing 43:i33–i33. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu046.1

Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Attreed NJ et al (2015) Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD009647 2015:CD009647. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009647.pub2

Poulia K-A, Yannakoulia M, Karageorgou D et al (2012) Evaluation of the efficacy of six nutritional screening tools to predict malnutrition in the elderly. Clin Nutr 31:378–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.017

Lim SL, Ang E, Foo YL et al (2013) Validity and reliability of nutrition screening administered by nurses. Nutr Clin Pract 28:730–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533613502812

Abbott RA, Whear R, Thompson-Coon J et al (2013) Effectiveness of mealtime interventions on nutritional outcomes for the elderly living in residential care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 12:967–981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2013.06.002

Nieuwenhuizen WF, Weenen H, Rigby P et al (2010) Older adults and patients in need of nutritional support: review of current treatment options and factors influencing nutritional intake. Clin Nutr 29:160–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.09.003

Gunnarsson A-K, Lönn K, Gunningberg L (2009) Does nutritional intervention for patients with hip fractures reduce postoperative complications and improve rehabilitation? J Clin Nurs 18:1325–1333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02673.x

Milne AC, Avenell A, Potter J (2006) Meta-analysis: protein and energy supplementation in older people. Ann Intern Med 144:37–48. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00008

Young AM, Mudge AM, Banks MD et al (2013) Encouraging, assisting and time to EAT: improved nutritional intake for older medical patients receiving protected mealtimes and/or additional nursing feeding assistance. Clin Nutr 32:543–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2012.11.009

Nijs K, de Graaf C, van Staveren WA et al (2009) Malnutrition and mealtime ambiance in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 10:226–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2009.01.006

NSQHS Comprehensive Care Standard. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/comprehensive-care-standard. Accessed 06 Nov 2022

Bell JJ, Young AM, Hill JM et al (2021) Systematised, interdisciplinary Malnutrition program for impLementation and evaluation delivers improved hospital nutrition care processes and patient reported experiences - an implementation study. Nutr Diet 78:466–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12663

Godfrey H, Cloete J, Dymond E et al (2012) An exploration of the hydration care of older people: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 49:1200–1211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roigk, P., Graeb, F., Geirsdóttir, Ó.G., Bell, J. (2024). Nutrition and Hydration. In: Hertz, K., Santy-Tomlinson, J. (eds) Fragility Fracture and Orthogeriatric Nursing . Perspectives in Nursing Management and Care for Older Adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33484-9_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33484-9_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33483-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33484-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)