Abstract

In today’s society, consumers expect products to be provided in packages. Nevertheless, this never used to be the case, and it is being argued that packageless alternatives will be developed more and more in the future. Utilizing the neo-institutionalist perspective, it is claimed that the package has been institutionalized in the extreme, thus making any thoughts of other alternatives almost impossible. However, it is asserted that packaging, as an institution, has started to be deinstitutionalized by sustainability-driven packaging-free consumption trends. This chapter reviews the essential functions and the history of packaging, the transformation of retailers due to the sustainability imperative, the zero-waste movement, and packaging-free retailing. It is then finalized with discussions on how packaging-free retailing was reborn, its obstacles, and suggestions for its future diffusion. It is concluded that an entirely packageless society would seem to be a utopia, while business-as-usual in packaging would be a bitter dystopia.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As we witness the “Anthropocene” era, the reversing of disastrous human impact becomes more vital. As one of the significant major challenges of this era, sustainable development requires the collaborative efforts of various stakeholders, including, more importantly than ever, businesses (Schaltegger et al., 2016), in order to decrease the negative impact of production and consumption (Tunn et al., 2019). Packageless consumption is gaining attention as regards building a more sustainable society. It is now clear that mainstream consumption and production patterns are energy- and resource-intensive (Mont, 2004). Backing precycling efforts, and thus creating the potential to decrease our dependence on recycling in the first place, packageless consumption has been considered to support waste reduction and minimization (Linn et al., 1994).

Although it is not new to view the consumer as the victim (Gabriel & Lang, 2006), recent editions of the well-established marketing management textbook position the consumer and the retailer face-to-face in the world of consumption as counterparties. Among all businesses, retailers occupy a specific position in fulfilling their duties with regard to noticing changes in consumer behavior and preferences, and market early on, as well as reflecting these changes in brands thanks to their position as an intermediary. Unlike in the past, retailers are no longer focusing solely on functionality, sales, and exchange. They are adding value to the products and services sold to consumers and offering these unique experiences. Thus, they are responding to changes and seizing opportunities in the marketing environment. As they perceive changes to consumers and markets, they also have the power to influence all the stakeholders along the value chain.

After the hard-to-repair damage humanity has inflicted on the world, the cry for sustainability has begun to be heard in all areas of life. “Packages are an inescapable part of modern life. They are omnipresent and invisible, deplored and ignored,” says Thomas Hine (1995 p. 2), the author of The Total Package. Packaging, which has become an essential part of products in the modern world, has also gained importance in sustainability efforts. These efforts include recyclable, biodegradable, or compostable packaging, packaging with less plastic waste, and packaging-free products, under appropriate conditions. The expectations and demands of both the consumer and the market, in this direction, have increased the interest being shown in new but old-fashioned packaging-free shopping options.

In modern society, consumers expect products to be provided in packages. Nevertheless, this never used to be the case, and we believe that packageless alternatives will be developed in the future. Employing a neo-institutionalist lens (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991), it is argued in this chapter that the package has become extremely institutionalized, thus making incongruence and any thoughts regarding alternative perceptions almost impossible. This chapter examines how packaging, which has become an institution over time, has started to be deinstitutionalized by sustainability-driven packaging-free consumption trends. It reviews the essential functions and history of packaging, the transformation of retailers due to the sustainability imperative, the zero-waste movement, and packaging-free retailing. We then finalize it with discussions on how packaging-free retailing was reborn, the obstacles it faces, and suggestions for its future spread. In short, we will try to explain how sustainability is leading us into returning to our grandparents’ tradition of packaging-free shopping.

Packaging: Concurrently Reveal and Conceal

Traces of packaging can be found in all marketing mix elements, fulfilling various functions and roles. A package is a container which is in direct contact with a product and which holds, protects, preserves, and identifies that product, facilitating its handling and commercialization (Ampuero & Vila, 2006). In the marketing literature, packaging is considered part of both the product and brand (Ampuero & Vila, 2006). Cochoy (2004, p. 213) explains packaging as “a screen that, while hiding what it shows, also shows what it hides.” Among other things, protection and communication are the main functions of packaging (Silayoi & Speece, 2007).

Packaging, with all its design elements, provides us with experiential, functional, and symbolic benefits (Underwood, 2003). It protects and contains the product; gains the attention of consumers; conveys a distinctive brand identity; transmits brand meaning; strengthens the consumer-brand relationship; communicates the brand’s features, quality, and value to consumers; and communicates brand personality via multiple structural and visual elements (Underwood, 2003). The package’s overall features underline the product’s uniqueness, originality, and quality (Silayoi & Speece, 2007). The package becomes the symbol that communicates implied meaning, favorable or unfavorable, regarding the product (Silayoi & Speece, 2007). Packaging is also a part of the competitiveness of a company in that it provides differentiation and positioning (Ampuero & Vila, 2006). Packaging can show products differently, but it teaches consumers more about these products than they could ever learn on their own (Cochoy, 2004).

Institutions impose one way of understanding the phenomenon, while blurring alternatives (Zucker, 1983). It may not be wrong to say that we are born, live, and die in some sort of package, making it a vital institution. Twede (2016, pp. 115–126) provides a thorough history of packaging over time by integrating both the retailer and consumer sides in a single narrative. For Twede (2016), the history of packaging, which dates back to ancient times, started with the earliest primitive packages made from leaves, skin, and gourds. Then, packaging moved from bulk shipping containers to household-sized packages (Twede, 2016). Between 1800 and 1890, new consumer packaging technologies emerged, such as glass bottles, wrappings, paperboard cartons, and cans (Twede, 2016). From 1890–1920, mechanization paved the way for mass production (Twede, 2016). Products started to be branded, and advertisements for packaged products emerged. Packaging was vital in changing the paradigm of consumption toward favoring national brands. Sales of packaged foods and beverages increased. Paper technology advanced and packaging became a strategic advantage. Between 1920 and 1940, packaging enabled brand owners to advertise and sell directly to consumers, and then the package turned into an advertisement (Twede, 2016). While Americans bought unbranded products by weight in those days, they started to buy branded products in boxes. Every sector of retail was affected by this revolution: The appearance and window display of the store changed, numbers of self-service retail stores increased, and the packaging supply industry emerged. World War II provided opportunities to improve food preservation and logistics (Twede, 2016). New flexible materials, such as aluminum foil and plastic film, were developed. By the 1950s, packaging was developing into a discipline and a profession, with related academic studies and educational activities increasing (Twede, 2016). Plastic became inexpensive enough to be used for packaging. The growing consumption of packaged products changed how people lived, and packaging regulations increased.

Packaging is viewed as a symbolic barrier limiting products’ naturalness (Szocs et al., 2021). In current image-laden societies, the package functions as a rhetorical tool for crafting brand myths (Kniazeva & Belk, 2007). Cochoy (2004) states that the packaged presentation of products has completely changed the relationship between consumer and product. As Twede (2016) explains, the 1950s and 1960s were the period of throw-away culture, consumerism, and style obsolescence. Post-1980s, materials became increasingly tailored for specific uses. Microwave-safe packaging was developed. Aseptic packaging was commercialized by TetraPak and adopted by the packaging industry. As a result, high-quality and convenient packaged food has come to dominate Western consumption. Packaging technology has also improved our ability to better serve segmentation and supply chain strategies. Sensors and electronics are leading to smart packaging. Consumer demand for packaged products is growing with economic development. The 1970s and 1980s marked the beginning of environmentally-conscious packaging. Packaging producers became more involved in waste management by designing for recycling (Twede, 2016, pp. 115–126). For the retail industry, the development of packaging is still an ongoing process through which innovative solutions are being offered on a regular basis.

Although its consequences can be debatable, recycling is continuously increasing, and packaging recycling is being found to be more economically feasible in Europe (Schyns & Shaver, 2021). But the share of packaging in the world’s plastic consumption is relatively high these days. The United States is one of the world’s largest plastic waste generators. For instance, in the US, supermarkets serve preshredded, grated, sliced or cut vegetables and fruit, convenient for consumers but also highly perishable and accompanied by a larger carbon footprint. Retailers are among the major contributors to packaging waste as they unnecessarily overpack their products. Therefore, packaging is one of the front and center issues when discussing waste management, how plastic harms the world, global warming, and the depletion of resources. As an institution, it can be claimed that various package properties have the potential to transform both the producer and the consumer. Despite all the functions it performs, packaging has evolved from a solution to a problem during its historical process. Moreover, in order to create a packageless society, it has even been argued that shopping as a practice has to be reinvented (Fuentes et al., 2019).

Retailers and Sustainability

Retailers are both individuals and organizations operating to deliver products and services to consumers, and to provide various benefits. Retailers have an important place in economic life. They offer diversified products and services, keep goods in stock on behalf of the consumer, exchange information between consumers and producers, sell products in small quantities, and provide extra services to consumers. In addition to all these functions, the retail industry’s sphere of influence is extensive when you consider its effects on other sectors. The retail industry, directly and indirectly, affects logistics, distribution, catering, cleaning, security, banking, construction, and storage services. Retailers, whose influence upon and place within economies is very significant, can potentially play a major role in ensuring the sustainability of consumption and production. Lai et al. (2010, pp. 15–22) clarify retailers’ role in sustainability using coordination theory. This theory explains how retailers implement sustainable and green retailing practices, outlining their distinctive role in greening their value chains. From this perspective, retailers provide an environmentally-friendly physical retail environment that facilitates interactions with customers: They transfer products from producers to consumers in an environmentally-friendly way, extending customers’ voices and providing feedback to suppliers, and promoting end-of-life product management. They also influence and support the entire value system. Similarly, Vadakkepatt et al. (2021) state that retailers are critical to a circular economy in which products undergoing their initial end-of-life stage are returned to the supply chain for continued use. Retailers can play a pivotal role in facilitating, propagating, and enforcing the retail supply chain’s practices of reduce, reuse, and recycle.

Sustainable and green retailing practices have been increasing. Pressure from customers, regulators, community groups, not-for-profit organizations, and NGOs pushes retailers into following green practices. Retailers must now be more environmentally-conscious than they have been in the past. They must embrace sustainability because consumers are more conscious of it and expect retailers to be sensitive to the environment, to cause minimal environmental harm and to bring about a positive social impact (Vadakkepatt et al., 2021).

It is asserted that global consumer capitalism has increased consumer vulnerability (Gabriel & Lang, 2006). Widespread greenwashing is depreciating consumer trust (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). However, retailers are attempting to be environmentalists in every imaginable area, from building environmentally-friendly stores to designing decor, materials, activities, suppliers, products, and promotions. In particular, large-scale retailers prefer environmentally-friendly suppliers, or they encourage suppliers to do less harm to the environment. They try to create distribution systems using sustainable products and packaging by collaborating with their suppliers and logistics businesses. In their retail activities, they try to cause as little harm to the environment as possible by using less energy and water, emitting less carbon, and using recyclable products. Some retailers try to show their sensitivity to this issue by building green retail stores that meet specific criteria regarding design, land use, water use, energy use, health and comfort, materials and resource use, operation, and maintenance. Retailers also try to do less harm to the environment and to protect it in their activities using the products they sell. By following the trend in consumer preferences, retailers are keeping increasing numbers of organic products on their shelves in their existing retail channels and opening new retail stores that sell only organic products. In this regard, some retailers prefer quickly biodegradable packages or bags, while others prefer environmentally-friendly packaging, or even unpackaged products. Green retailing and sustainability practices have several benefits to retailers: They provide the opportunity to attract consumers who want to buy environmentally-friendly products, also improving brand equity, building customer loyalty, attracting investment, cutting the cost of packaging, waste disposal, warehousing, electricity, and water, and, perhaps most importantly, offering a means of differentiation and competitive advantage (Vadakkepatt et al., 2021). Vadakkepatt et al. (2021, p. 63) define a sustainable retailer as one that goes beyond mere economic considerations and includes environmental and social considerations for the benefit of current and future generations, taking into account the long term. In short, retailers have much power and influence when it comes to making the market more sustainable, due to their position.

Zero Waste Movement: Packaging-Free Retailing

Although bulk sales in traditional bazaars in the underdeveloped and developing world are perceived as old-fashioned, packaging-free supermarkets, such as the “Original Unverpackt” in Berlin, resemble new avenues toward a packageless society (Scharpenberg et al., 2021). In addition to packaging-free supermarkets, innovative reuse models that can minimize package waste are on the rise in FMCG retailing (Muranko et al., 2021). Significant changes in societal norms and consumer attitudes are increasing businesses’ need to consider and integrate sustainability into their core strategies (Vadakkepatt et al., 2021). The zero-waste movement and zero-waste, or packaging-free retailers reflect this bilateral sustainability need. The number of sustainably-minded businesses is currently increasing. Many independent retailers also offer zero-waste products. The zero-waste retailer is one solution to the plastic crisis and packaging overheads.

Sustainable businesses aiming to reduce or eliminate packaging have various names, although no clear distinctions exist between them. These are; zero-waste or zero-packaging stores, packaging-free bulk product stores, packaging-free stores, packageless retailers, and unpackaged product stores. These new stores are the modern version of the traditional bulk store, but the zero-waste movement is more closely related to the sustaining of environmentally-friendly lifestyles. Packaging-free shopping is an example of an increasing joint initiative for pro-environmental behavioral change, focusing on removing unsustainable objects rather than “greening” existing products and objects (Fuentes et al., 2019). The key to packaging-free shopping is the notion that packages are problematic. It becomes clear that consumers are concerned about waste, viewing packaging as a waste problem (Fuentes et al., 2019).

While products begin their useful life when purchased, packages have usually completed their useful life then (Twede, 2016, p. 126). Therefore, zero-waste or packaging-free shops are trying to eliminate the need for single-use packages. “Packaging-free” means consumers can buy groceries unpackaged at the supermarket, from different dispensers (Scharpenberg et al., 2021). Packaging-free shopping is a retail system that sells unpackaged consumer goods by weight or volume, depending on whether these products are solid or liquid, in simplified store-provided packaging or in a customer-brought container (Louis et al., 2021). The working principle used by these stores generally entails consumers bringing their own containers, which can be washed and reused, refilled with whatever is needed, and then paid for according to weight or volume. Tap-like refilling stations are used by packaging-free, zero-waste retailers. Pasta, rice, grains, legumes and pulses, dried fruit, oils, milk, oat milk, peanut butter, mayo, vegan products, salt and spices, cleaning products, such as laundry and kitchen detergents, and personal care products can all be sold by these stores. Packaging-free retailers have inspired mainstream retailers. International retail giants, such as Aldi, Tesco, Trader Joe’s, Waitrose, Sainsbury’s, Asda, and M&S, are adopting new sustainability strategies by offering measures for decreasing the amount of packaging. They offer some zero-waste shopping at their stores. This offer can be in the form of a corridor section at a market, or just a refill station.

Packaging-free retailers bring the potential to reduce the environmental pressure caused by plastic packaging in the food industry. Packaging-free shopping may have the advantage of lower prices, customization, and reduced food waste. Moreover, packaging-free retailers generally support small start-up companies, women-led and women-owned businesses, grassroots charities serving their products, companies using ethically-sourced ingredients, minority-owned businesses, and more sustainable companies. One of the most critical aspects of packaging-free retailers is supporting local producers and businesses. Small packaging-free entrepreneurs create community hubs in the neighborhoods where they operate, which is quite similar to how it was in the past when sellers and buyers knew each other. Packaging-free retailers have a community-driven model that creates a community. It can be said that businesses operating according to this model are not only meeting the demands of many consumers in this regard, they are also undertaking the task of educating new consumers about this sustainable system.

As an intermediary between consumers and producers, retailers support consumers by offering less packaged products or completely unpackaged ones, making packages refillable and reusable, and reducing the frustration caused by packaging waste. On the other hand, they encourage manufacturers and suppliers to make innovative product designs that eliminate packages or make them reusable, and to make permanent packages ready for recycling (Vadakkepatt et al., 2021, p. 67). For example, on the understanding that less is more with regard to packages, the cosmetic brand Lush aims to present its products unpackaged; in the brand’s own words, naked. Sixty-five percent of Lush products, which can be used all year round, are unpackaged. The remaining Lush products are packaged using recycled and recyclable materials.

Re-Birth of Packaging-Free Shopping

First, we should acknowledge that going package-free is not easy, either for consumers or retailers. It is asserted that consumption practices are based on crystallized social understandings (Rapp et al., 2017). Although packaging-free shopping is being touted as a new sustainable consumption trend, or a new form of sustainable consumption, it is not new. As a child in the mid-80s, one of the authors used to visit his grandparent’s “bakkal” (i.e., a small convenience store in Turkey with historical and cultural connotations), where it was still possible to experience, multisensorially, packaging-free retailing. Packageless living is not a new concept. It is something that previous generations understood because they reused, repaired, and repurposed things. Packaging-free shopping is a way of getting things back to how they used to be. Surprisingly, this is not the first rebirth of the bulk product trend. Johnson (1984) states that the trend of marketing foods in bulk bins started in the 1960s, in small health food stores and food co-ops, then spreading to the entire supermarket industry.

Even though it is one of the oldest consumption patterns, packaging-free shopping is still one of the newest consumption trends, especially in developed countries. Before modern packaging, people used natural materials for food packaging to keep food fresh and delicious, and to preserve, protect and store it. These methods and materials differed culturally and geographically. Every culture has traditional food packaging methods that depend heavily on natural resources and these are creatively made by hand. In the Turkish food culture, cheese and similar foods were pressed into soil and animal leather pots. Salting, smoking, drying, canning, storing in honey or olive oil, and burying in soil or snow are various forms of traditional packaging and storage alternatives. In the past, many products, such as milk and dairy products, pulses, rice, pasta, cereals, flour, nuts, and spices, were also sold unpackaged in large containers. Then, packaged food products appeared on supermarket shelves and replaced packaging-free shopping. Packaged products have become an indicator of development and modernity. Consumers have begun to prefer the new order in which everything is in packages, compared to traditional shopping without packages. With the development of modern packaging, even prepeeled oranges, bananas, or avocado halves in plastic boxes can be found in supermarkets.

Currently, and without overpackaging, societies are trying to move away from packages that do not dissolve in nature. Old knowledge and traditional methods have the potential to create more sustainable consumption solutions. They may provide valuable information and inspiration regarding future sustainable practices. New practices can be created by combining traditional practices or products with new technologies. Rapp et al. (2017) found that consumers link packaging-free shopping to the past and tradition and a return to authenticity, recalling a neighborhood store that offers a seller–buyer relationship based on trust and familiarity.

Overcoming the Barriers to Packaging-Free Shopping

Consumers of packaging-free products are generally keen on recycling and protecting the environment, valuing these products’ convenience, healthiness, and origin (Rapp et al., 2017). Packaging-free shopping often requires consumers to adapt to a new way of shopping by giving up some of the convenience of regular shopping, and their old shopping habits. Moreover, removing packaging from the practice of shopping is problematic because of the functions it performs. Packaging-free shopping can be criticized because it transfers the functions of the packaging to consumers as an extra burden (Fuentes et al., 2019). The prime barriers to purchasing packaging-free products (Marken & Hörisch, 2019) are a lack of awareness of the existence of the offer, the unsuitability of the product range, impracticalities, and the inconvenience of making the purchase because consumers need to plan, carry reusable containers, and put more time into the shopping process.

Is the answer to a packaging-free society a different kind of packaging? Fuentes et al. (2019, p. 264) discuss the potential of packaging-free shopping as an emerging or re-emerging mode of shopping that is being threatened by easy-to-adapt, convenient sustainability strategies, such as environmentally-friendly packaging, normal shopping modes such as regular supermarkets, and more reasonable prices for regular shopping. Consumers are used to the convenience of prepacked foods, so retailers adopting a packaging-free business model should use technologies that facilitate the shopping process and create an enjoyable and nostalgic experience. Fuentes et al. (2019) found that, to be able to successfully remove a key artifact - packaging - from the practice of shopping, the practice itself must be reinvented. Developing packaging-free shopping thus requires; the reframing of the shopping practice by making it meaningful in a new way; the reskilling of the consumer by developing the new competencies needed for performance; and the rematerialization of the store by changing the material arrangement making this mode of shopping possible.

Institutions also have lifespans (Davis et al., 1994). The erosion or discontinuity of an institutionalized organizational activity or practice is called deinstitutionalization (Oliver, 1992, p. 564). Sustainability concerns gradually result in the deinstitutionalization of packaging. A narrative on the institutionalization of packaging-free consumption is the opposite of the historical institutionalization of the package (Table 8.1 vs. Table 8.2). It is self-evident that the process starts with environmentally conscious packaging. Future efforts in marketing should focus on what has been done, for packaging, for over a century. According to the characteristics of any grand challenge (George et al., 2016), this requires the collaborative and coordinated efforts of multiple stakeholders. Therefore, the retail industry should proactively address this issue.

Conclusion

Packaging-free shopping is a form of sustainable business model that meets the demands and needs of environmentally-sensitive consumers, reduces the harm that consumption causes to the environment, and contributes positively to a better world. It is impossible to avoid being a consumer, but there are ways to improve sustainable living. One consumer motivation when it comes to packaging-free consumption relates to not seeing the world as something that has been freely given. In contrast to many alternatives meeting consumer ambitions to be sustainable, packaging-free retailing supports the wellbeing of society and the world better. Packaging-free retailing and consumption not only protect the natural environment, they also enable local, small, sustainable businesses to exist within the economic system. Packaging-free retailing supports localization, one of the alternative ways of consuming that a sustainable world needs. This is a way of preserving heirloom seeds and plants and locally-grown products, as well as consumption traditions and culture, by passing these on to new generations. Packaging-free retailers also respond to consumer needs regarding nostalgia, intimacy, and being a part of the community. Therefore, when packaging, something which performs many functions for the product and creates many different meanings for the consumer, disappears, it takes on a brand-new function by creating completely different meanings.

Does packaging-free retailing offer a glimpse into the future of the packageless society? For us, an entirely packageless society would seem to be a utopia, while business-as-usual packaging would be a bitter dystopia. The deinstitutionalization of packaging requires complicated institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006) during which the disregarding of contextual dynamics may bring unexpected consequences. Apathy can cause various other sustainability issues, such as pollution and food waste, or even the collapse of the packaging industry, leaving many jobless. Images of the scattered plastic packages of well-known brands waiting to be burned at an uncontrolled facility harshly reflect how the burden is being transferred from developed countries to under-developed ones.

However, retailers must allow the conviviality of sustainable packaging, and packaging-free options are the probable future scenario for retailing. It is undeniable that retailers have an impact on all the supply chain participants, such as producers, wholesalers, and consumers, as well as the indirect participants along the value chain, and that retailers have the ability to make these actors more sustainable. Twede (2016, p. 127) explains the history of packaging as a story of adaptation, something which clearly indicates its future. On the other hand, several physical and behavioral barriers to the adoption and spread of packaging-free shopping do exist. Despite all its positive contributions, these obstacles prevent packaging-free retailing from being institutionalized and thus becoming a standard business model. It is suggested that retailers should strive to find ways of bringing together their supply chains and market demands regarding the sustainable future. They focus on areas that fit with their target customers and business models instead of engaging with all aspects of the sustainability discourse. Therefore, retailers are taking the dominant aspects of sustainability and turning them into market actions that can be taken within existing structures and can find sufficient support and acceptance among consumers in order to continue their businesses economically and sustainably.

References

Ampuero, O., & Vila, N. (2006). Consumer perceptions of product packaging. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(2), 100–112.

Cochoy, F. (2004). Is the modern consumer a Buridan’s donkey? Product packaging and consumer choice. In K. M. Ekström & H. Brembeck (Eds.), Elusive consumption (pp. 205–227). Berg.

Davis, G., Diekmann, K., & Tinsley, C. (1994). The decline and fall of the conglomerate firm in the 1980s: The deinstitutionalization of an organizational form. American Sociological Review, 59(4), 547–570.

Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87.

Fuentes, C., Enarsson, P., & Kristoffersson, L. (2019). Unpacking package free shopping: Alternative retailing and the reinvention of the practice of shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50(2019), 258–265.

Gabriel, Y., & Lang, T. (2006). The unmanageable consumer. SAGE Publications Ltd..

George, G., Howard-Grenville, J., Joshi, A., & ve Tihanyi, L. (2016). Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 1880–1895.

Hine, T. (1995). The total package. Little.

Johnson, S. C. (1984). Consumers’ attitudes towards shopping. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 15(1), 15–25.

Kniazeva, M., & Belk, R. W. (2007). Packaging as vehicle for mythologizing the brand. Consumption Markets & Culture, 10(1), 51–69.

Lai, K., Cheng, T. C. E., & Yang, A. K. Y. (2010). Green retailing: Factors for success. California Management Review, 52(2), 5–31.

Lawrence, T., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and institutional work. In T. Lawrence & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organization studies (pp. 215–254). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Linn, N., Vining, J., & Feeley, P. A. (1994). Toward a sustainable society: Waste minimization through environmentally conscious consuming. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(17), 1550–1572.

Louis, D., Lombart, C., & Durif, F. (2021). Packaging-free products: A lever of proximity and loyalty between consumers and grocery stores. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102499.

Marken, G., & Hörisch, J. (2019). Purchasing unpackaged food products. An empirical analysis of personal norms and contextual barriers. NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum, 27, 165–175.

Mont, O. (2004). Institutionalisation of sustainable consumption patterns based on shared use. Ecological Economics, 50(1), 135–153.

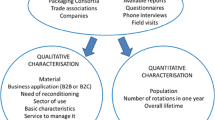

Muranko, Ż., Tassell, C., Zeeuw van der Laan, A., & Aurisicchio, M. (2021). Characterisation and environmental value proposition of reuse models for fast-moving consumer goods: Reusable packaging and products. Sustainability, 13(5), 2609.

Oliver, C. (1992). The antecedents of deinstitutionalization. Organization Studies, 13(4), 563–588.

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (Eds.). (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. The University of Chicago Press.

Rapp, A., Marino, A., Simeoni, R., & Cena, F. (2017). An ethnographic study of packaging-free purchasing: Designing an interactive system to support sustainable social practices. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(11), 1193–1217.

Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Hansen, E. G. (2016). Business models for sustainability: A co-evolutionary analysis of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and transformation. Organization & Environment, 29(3), 264–289.

Scharpenberg, C., Schmehl, M., Glimbovski, M., & Geldermann, J. (2021). Analyzing the packaging strategy of packaging-free supermarkets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 292, 126048.

Schyns, Z. O. G., & Shaver, M. P. (2021). Mechanical recycling of packaging plastics: A review. Macromolecular Rapid Communications, 42(3), 2000415.

Silayoi, P., & Speece, M. (2007). The importance of packaging attributes: A conjoint analysis approach. European Journal of Marketing, 41(11/12), 1495–1517.

Szocs, C., Williamson, S., & Mills, A. (2021). Contained: Why it’s better to display some products without a package. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1–16.

Tunn, V., Bocken, N., van den Hende, E. A., & Schoormans, J. (2019). Business models for sustainable consumption in the circular economy: An expert study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 212, 324–333.

Twede, D. (2016). History of packaging. In D. G. B. Jones & M. Tadajewski (Eds.), The Routledge companion to marketing history (pp. 115–130). Routledge.

Underwood, R. L. (2003). The communicative power of product packaging: Creating brand identity via lived and mediated experience. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 11(1), 62–76.

Vadakkepatt, L. B., Winterich, K. P., Mittal, V., Zinn, W., Beitelspacher, L., Aloysius, J., Ginger, J., & Reilman, J. (2021). Sustainable retailing. Journal of Retailing, 97(1), 62–80.

Zucker, L. G. (1983). Organizations as institutions. In S. B. Bacharach (Ed.), Research in the sociology of organizations (pp. 1–47). JAI Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ağlargöz, O., Ağlargöz, F. (2024). Toward a Packaging-Free Society: A Historical Journey of Institutionalization and the Way Forward. In: Bäckström, K., Egan-Wyer, C., Samsioe, E. (eds) The Future of Consumption. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33246-3_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33246-3_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33245-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33246-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)