Abstract

The aim of this study is to provide research performing organisations and research funding organisations (RPOs and RFOs) with practical advice on how to engage in an effective RRI institutionalisation. Therefore, we first looked at the most relevant drivers, challenges, and the most beneficial good practices potentially affecting RRI institutionalisation within RPOs and RFOs across Europe through a multi-step, multi-stakeholder consultation approach. The broad set of drivers, barriers and good practices identified at the consultation was methodologically divided into structural, cultural and interchange-related aspects. These aspects can theoretically exercise a positive or negative impact on the RRI institutionalisation, and their validity was tested in Living Labs by six organisations. By categorising these six implementers in terms of RRI readiness we were able to identify key factors and describe specific organisational circumstances conducive to a successful adoption and use of RRI principles and practices for three organisational types of RPOs/RFOs.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The main objective of the ETHNA project funded by the European Commission under the Horizon 2020 programme was to test the implementation potential of a novel governance, management and procedural system for Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI). This RRI governance systemFootnote 1 aimed to design and promote sustainable research and innovation practices respecting state-of-the-art ethical standards and other policies facilitating the adoption of RRI principles. The purpose was to develop a flexible system which can be adapted at as many research-performing organisations and research funding organisations (RPOs and RFOs) as possible.

Therefore, the envisaged concept defined only the broader competences, functions and structure of an ‘ideal’ RRI governance system with a proposed set of ethical management tools, and included good practices of various ethical management methods. The goal was to provide a truly practical guide of RRI institutionalisation, tailored to the vastly different circumstances, needs and requirements of RPOs and RFOs across Europe.

We define institutionalisation in practical terms, i.e., as the process of embedding RRI practices in a RPO or RFO in order to achieve some desirable organisational change where, at the very end of the process, RRI becomes an integral part of the organisation’s identity, structure and culture which is not dependent on the effort of specific people [1].

In order to enhance the practical usability of the conceptual RRI governance system, the most relevant drivers behind RRI institutionalisation and the most serious barriers hindering the adoption or successful use of RRI within RPOs and RFOs across Europe had to be explored and better understood. This was achieved by a multi-stakeholder consultation process consisting of several steps, also striving to identify good practices of RRI institutionalisation.

The identification and analysis of these drivers, barriers and good practices took place before the pilot implementation (test phase) of the RRI governance system with the aim of providing future pilot implementers with practical advice on how to mitigate the risk of potential challenges that could threaten the success of the RRI institutionalisation process (pre-pilot evaluation).

The pilot implementation was carried out within six Living Labs. A Living Lab is a social, physical and/or mental space for social innovation and experimentation where different actors – both internal and external to the implementing organisations – come together with the objective to deal with a complex problem, and to come up with new and better solutions through dialogue, testing and reflecting. In our specific case internal and external stakeholders in six RPOs and RFOs pulled their resources to co-create, experiment with and evaluate the feasibility of the conceptual ideas and implementation steps embedded in the envisaged RRI governance system.

The Living Lab test phase ended with an in-depth evaluation of the process and outcomes, highlighting also the necessary conditions required to initiate, manage and implement RRI institutionalisation in different RPOs and RFOs. This evaluation also considered the specific drivers, barriers and good practices of different Living Lab contexts (post-pilot evaluation).

In practical terms the pre-pilot evaluation provided us with a broad set of potential drivers of and barriers to RRI institutionalisation that might be valid for different RPOs and RFOs. This broad set of factors were subsequently validated during the concrete implementation steps of the Living Labs, i.e. by using a small sample of diverse RPOs and RFOs a post-pilot evaluation was carried out where, on the basis of an original methodological framework, the pre-pilot evaluation results were placed into a broader context.

The contextualisation involved the understanding of the specific organisational circumstances and characteristics related to the most relevant identified drivers of and barriers to RRI institutionalisation.

The aim of this study is to use this contextualised data in order to provide RPOs and RFOs with practical lessons learnt on the incentive factors and challenges of RRI institutionalisation, coupled with specific measures on how to overcome such hindrances in the most effective way. We strive to give recommendations that can be useful for different types of RPOs and RFOs looking into the possibilities of adopting RRI principles and practices.

2 The Multi-stakeholder Consultation - Process and Outcomes

As detailed in the Introduction, a draft concept for a RRI governance system was elaborated in the course of 2021, providing a first interpretation of the proposed competences, functions, structure and ethical management tools of the system. However, a more nuanced, evidence-based and practical guidance on how to foster RRI institutionalisation for the foreseen target group of RPOs and RFOs was missing from this draft.

In order to make the concept adaptable to different organisational circumstances, key organisational factors advancing or hindering the institutionalisation of RRI within European RPOs and RFOs had to be identified and evaluated. For this purpose, a multi-stakeholder consultation was set up and implemented, gathering detailed information from a broad range of stakeholders across Europe on the status of RRI institutionalisation, the relevant drivers and barriers concerning the adoption of RRI principles and practices, as well as on the related good practices and implemented measures.

2.1 The Process of the Multi-stakeholder Consultation

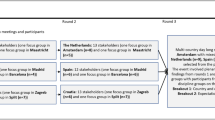

The multi-stakeholder consultation was conducted between January and October 2021 before the Living Lab pilot implementation, consisting of a preliminary phase and three subsequent phases, i.e., interviews, workshops and a global survey. Each stage focused on better understanding the relevant drivers, barriers and good practices concerning the adoption of RRI measures in RPOs and RFOs (Fig. 1).

The preliminary phase used a questionnaire to be answered until the end of January 2021 only by the six Living Lab implementers to assess their currently available and missing RRI tools, initiatives and aspects, and their future plans to deal with missing RRI dimensions. Importantly, the questionnaire helped evaluate the interdependencies between organisation types, research area(s), organisational structure and RRI uptake, which contributed to developing a future self-assessment method for ‘RRI readiness’ (RRI institutionalisation quadrants) and outlining the focus of the interviews and workshops.

In the first consultation phase 25 semi-structured interviews were conducted between April and June 2021 with mid- or high-level representatives of European RPOs and RFOs actively engaged in RRI governance or specific RRI keys. People familiar with key concepts of RRI and organisational or national adoption of RRI principles and keys were interviewed about their expertise and understanding of RRI, the organisational drivers and barriers of RRI institutionalisation, as well as good-practice examples or ideas.

We aimed to involve stakeholders from across as many countries, RRI keys and organisation types as possible, also striving to conduct interviews with persons working in research (or innovation) performing businesses and civil society organisations. Therefore interviews were made with representatives of the following ten countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Norway, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain. Altogether seven RFOs and 18 RPOs (including five businesses and two civil society organisations) were interviewed.

Their opinion was considered important as an input for the Living Labs that by definition aim to foster interactions of four stakeholder groups within the knowledge economy, namely academia, business, policy-makers and civil society [3,4,5].

Based on the responses of the interviews, five online workshops were organised per RRI keys with Living Lab implementers and external expert stakeholders (participant number ranging from 11 to 17) as a second consultation phase between July and September 2021. The workshop participants discussed in more detail the factors driving or hindering RRI institutionalisation in RPOs and RFOs.

The workshops aimed to obtain relevant observations and develop recommendations for the Living Labs with respect to the relevant drivers, incentives, barriers and organisational strategies and practices for RRI governance. Their main outcome was the ranking of drivers and barriers of RRI institutionalisation per RRI keys and organisational types, which was verified by an online survey in the third consultation phase.

The online survey was sent in October 2021 to a broad group (10.000 +) of potentially relevant expert stakeholders identified through a Web of Science database search with the aim of assessing the relevance of the identified drivers, barriers and good practices of RRI institutionalisation. Altogether 888 responses were received from 69 countries with a balanced gender representation, involving the opinion of mostly senior experts (55% having more than 15 years of experience)Footnote 2.

After filling out general demographic and organisational information, the respondents rated the perceived relevance of the RRI incentives, barriers and good practices that were the highest ranked at the end of the second consultation phase (using a Likert scale of 1–10). Thus, the survey confirmed the results of a smaller, unavoidably biased sample on a global scale with the support of RRI experts. These results are summarised in the next Section.

2.2 Lessons Learnt from the Multi-stakeholder Consultation

To present our findings, we chose to use as a basis the theoretical framework developed by [6] in the Horizon 2020 project RRI-Practice that was further refined in [7]. This framework was already utilised in the workshop phase when relevant RRI drivers and barriers, as well as potential organisational actions were divided into structural, cultural, and interchange perspectives. All three perspectives focus on different aspects within organisations (RPOs and RFOs) that might contribute to or hinder the institutionalisation of RRI or its keys.

The first perspective focuses on regulative and normative aspects that structure and standardise organisational behaviour. Structural aspects include formalised roles and positions, mandates, responsibilities, decision-making structures in the organisation, namely persons or units specifically tasked with RRI-related duties in RPOs and RFOs such as ethics boards or research integrity offers, and the related formal and informal documents, namely concepts, norms, standards, procedures and strategies, such as code of ethics, gender equality plans open science policy guidelines.

The second perspective focuses on cultural aspects and, consequently, deals with the informal and tacit organisational structures that influence the adoption of RRI standards and practices. These structures might explain the difference and the interconnected relation between policy goals and practical behaviour within organisations. Cultural aspects include organisational cultures, values, and identities, i.e. for the purposes of this article, the perceptions about RRI.

Third, the interchange aspects are based on the observation that organisations are not only influenced by their structure and culture but also by their interactions with other organisations in their broader environment. Thus, these aspects focus on drivers or barriers stemming out of but connected to the organisation, such as impacts of the broader policy landscape or research culture [7].

RRI governance was regarded throughout the consultation as a horizontal, cross-cutting dimension, which means it had gained an elevated role which was then reflected by Living Labs through their focus on the whole RRI governance structure. Table 1 summarises the aspects deemed most relevant by stakeholders in terms of adoption and successful use of RRI in their respective organisation. A more detailed analysis at the level of specific RRI keys may be of interest but is outside the scope of this article.

As regards the potential drivers for RRI, the stakeholders identified two key structural factors for a successful RRI institutionalisation process, namely a supportive (higher and mid-level) management, and support structures and practices that can take many forms within an organisation, including pilot programmes dedicated to certain RRI keys, organisational units or infrastructure dealing with specific RRI keys. A management keen on furthering RRI also should strive to adopt organisational mandates, regulations or strategies that prescribe concrete policy goals aimed at fostering RRI.

Such formalised drivers are more effective in an organisational environment aligned through values or identity with the overall concept and specific aspects of RRI. RRI should become part of the culture within an organisation when research activities at all stages take into consideration RRI keys, such as ethics and research integrity. Organisational ‘facilitators’, i.e. persons or units already engaged in RRI and willing to share their knowledge and skills with others, are perceived crucial by stakeholders to embed RRI both in the culture and mandate of a given organisation.

If internal incentives are not strong enough to facilitate the uptake of RRI, external drivers can gain in importance. More and more often research funders by mandate aim to ‘nudge’ RPOs to adopt RRI aspects through assessment criteria (compulsory gender equality plans), monitoring requirements or other policies. In addition, a proactive management might seek to voluntarily align organisational practices with national standards or international benchmarks in various RRI keys.

Nevertheless, potential barriers to RRI might counteract with the impact of these drivers. The majority of the stakeholders consider the lack of resources as the most influential barrier. This simply means that there are not enough employees to deal with RRI or researchers under constant pressure have no time to engage in RRI. The adequate funding is also often missing to compensate for such extra work.

This manifests in a lack of or underdeveloped support structures and practices when RPOs are not able to focus on RRI aspects in addition to their ‘core’ research activities. The root problem might be the lack of engagement from a managerial level but such a state might merely develop due to financial and time constraints in spite of the better efforts of the leadership.

Such management efforts might be also hampered by a lack of awareness or understanding of RRI and its keys. RRI as a concept is still not completely clear for many members of the research community, especially if they do not deal with EC research and innovation policies or projects. In many cases some RRI keys are present in the organisation but not perceived as part of the RRI concept. Knowledge is fragmented between units, teams and researchers resulting in a lack of explicit support for RRI in organisational values, standards and long-term vision.

The fragmentation might be exacerbated by confusing RRI-related policies, strategies or mandates of policy-makers or research funders in different research fields or countries that sometimes contradict each other or give no clear guidance. Such a state of affairs might demotivate even the most dedicated and diligent researchers.

The stakeholders described several organisational measures to combat such demotivation trends and foster RRI institutionalisation. Even though the aim of aligning the organisation – or its dedicated units – with the most important external standards and funding requirements might seem inconceivable in the short term, more practical steps at lower levels can be started to foster RRI uptake.

In order the decrease fragmentation of knowledge on RRI, the organisation should carry out knowledge pooling measures, e.g., by using internal information repositories to check what RRI-related documents are already available within the institution, or by implementing a work environment survey to gather data on the readily available institutional knowledge on RRI-related principles and measures.

Reflection spaces organised in formal or informal settings, such as dialogue sessions or workshops, with the aim of knowledge pooling might contribute to understanding how to build RRI concepts and practices into research activities. In addition to internal knowledge sharing, networking with external stakeholders within and outside of other RPOs might also facilitate knowledge transfer with regard to the identification of common problems and solutions in RRI issues.

The increased and less fragmented knowledge base should be compiled and disseminated in practical guides that also aim to reduce the lack of conceptual and terminology clarity of RRI. In order to raise awareness of RRI issues, motivate people to get engaged and gain top-down support, the benefits of RRI should be explained in a clear and understandable manner.

The sustainability of such measures can be ensured by a couple of good practices frequently mentioned by the stakeholders, such as practical training or more formal education opportunities offered to researchers and other employees, institutional or departmental awards or other recognitions given to individuals or teams raising awareness of or tackling RRI-related issues. Finally, revised performance metrics evaluating the progress of RRI uptake at organisational or departmental level would be crucial for ensuring sustainable positive changes.

Evaluating organisations through the lens of the aforementioned structural, cultural and interchange aspects provide a broad overview on the possible uses of RRI in RPOs and RFOs but their practical relevance could only be validated through the actual Living Lab implementation also taking into consideration the more theoretical findings of the multi-stakeholder consultation with the involvement of external stakeholders.

The above summarised results of the stakeholder consultation supported the Living Lab implementation in two significant respects. First, they contributed to the development of a practical toolbox to support implementation approaches and to provide Living Lab implementers with options to spark ideas on the potential challenges and ways to overcome those (while helping understand what drives the institutionalisation of RRI in the first place). Second, the results laid the groundwork for categorising the potential usefulness and adaptability of the concept in different organisational settings, which will be described in-depth in the next subsection.

2.3 The RRI Institutionalisation Quadrants

We found two critical factors to assess the given organisation’s readiness for RRI institutionalisation through the analysis of the initial results gained from the different phases of the multi-stakeholder consultation. Notwithstanding the fact that there are other relevant institutional factors influencing the chances of a successful adoption and use of RRI by RPOs and RFOs – such as among others size, country, research area, funding sources – two dimensions can be considered as essential for the institutionalisation of RRI: the leadership and the base (Fig. 2).

First, the leadership represents the commitment of the higher or mid-level management in terms of top-down support received by organisational stakeholders for RRI institutionalisation. The leadership might provide such top-down support in various ways ranging from a passive commitment to a more active involvement, such as the heightened awareness level of certain RRI-related issues, the prevalence of a clear vision on RRI, the willingness to adapt conditions or allocate the required – human or financial – resources for a better RRI institutionalisation.

Source: ZSI’s own rendition, taken from [9]

The RRI Institutionalisation Quadrants – Leadership and Base.

Second, the base means the strength of the organisational structures in the support of RRI institutionalisation that are launched and managed at various (lower) levels of the organisation. As opposed to the leadership dimension, these support measures are mostly started from bottom-up, enabled by the values, awareness, skills and knowledge of the research staff and other organisational stakeholders.

Applying leadership to the y-axis and the base to the x-axis results in a two-dimensional system with four quadrants that can be characterised as follows:

A strong leadership but weak base (top left quadrant) means that initiatives to drive the institutionalisation of RRI may already be under way but, generally, have not borne fruit yet, i. e. RRI norms and practices have not been broadly adopted by the base yet. However, the leadership is strong in terms of providing guidance on designing and implementing relevant activities. This guidance could be reflected in an increased awareness, sense of urgency, willingness, clarity of vision, leadership skills, resources, etc.

A strong base but weak leadership (bottom right quadrant) means that RRI initiatives can already be found in the organisation however the leadership is weak in terms of RRI institutionalisation. This weakness might entail that the management might not have heard about such initiatives, might not care, or might think that these initiatives are too specific or small to be transferred, scaled up, or adopted by all organisational units. In theory, the organisational focus should first lie on spreading RRI norms and practices locally, on building showcases, and on connecting to similar efforts – both internal and external ones – to build a critical mass and reach and engage the leadership.

A strong leadership and strong base (top right quadrant) means that both leadership and base are aligned in terms of RRI institutionalisation needs and efforts. Such organisations show advanced levels of RRI institutionalisation and might have a long tradition of reflecting and adjusting their research practices, of reacting to external normative efforts (e.g., the adoption of standards), and of building institutional support structures and mechanisms. The guidance in this case will focus on giving impulses with the aim of further refining the institutionalisation efforts and adopt an anticipatory perspective in terms of future developments [9].

The devised RRI governance system was designed to work for all quadrants, with the exception of the lower left quadrant, i.e., weak leadership in combination with a weak base. A major prerequisite for the RRI institutionalisation is that at least one dimension needs to be at least somewhat strong, otherwise there is nothing to build on. For a successful institutionalisation process, both dimensions need to become strong in the long run.

This RRI Institutionalisation Quadrants helped the Living Labs to gauge their strength and determine their level of commitment to the options provided by the RRI governance concept.

The next Section will give an overview on the Living Lab implementation, its evaluation process and the most relevant evaluation results that are summarised with the help of the above-described conceptual framework.

3 The Living Lab Implementation – Process and Evaluation

In order to test the practical applicability of the finalised RRI governance concept in different RPOs and RFOs, it was planned and implemented at six organisations based in five different European countries.

The following organisations participated in the Living Lab experiment: University Jaume I (UJI) [10], a large public university from Spain; the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), the largest public university in the country; the Education and Youth Board (Harno), a funding agency from Estonia; the Science, Technology and Business Park (ESPAITEC), a Spanish technology park; the Institute for the Development of New Technologies (UNINOVA) [11], a multidisciplinary, independent, and non-profit research institute from Portugal, and Applied Research and Communications Fund (ARC Fund) [12], a non-profit research and innovation policy institute from Bulgaria..

The implementation process followed the Living Lab methodology, and was divided into six stages (planning; construction; consultation; refinement; testing; review) lasting approximately one year (November 2021 – October 2022), with some institutions ultimately experiencing delays in certain process stages.

Since not much time has passed since the official end of the Living Lab experiment at the time of writing this studyFootnote 3 it is not yet feasible to assess the scope of the institutional changes induced by the implementation process as the actual impact will only become tangible in a longer timeframe. However, it is already possible to draw conclusions at a more practical level. Therefore, the evaluation process focused on the most common drivers and barriers of implementation, highlighting concrete actions and good practices emerging from the process, as well as outlining necessary conditions for supporting the organisational uptake of RRI in the six implementing organisations.

The evaluation took place between September and November 2022 and contained the following steps:

-

1.

DBT organised two rounds of two online, 3-h participatory evaluation workshops in September and October 2022. The first round of workshops was held with representatives of the project partners participating in Living Labs, while the second round of workshops involved internal and external stakeholders supporting the Living Lab implementation.Footnote 4.

The workshops were organised as semi-structured events focused on the added value of the RRI institutionalisation process in general, as well as the particular experiences encountered in the actual implementation process. The workshops employed a diversity of exchange formats to support mutual learning and feedback gathering as needed. This structure provided the participants with great flexibility to engage in dialogue and generate collective reflections on the insights and lessons learned from the implementation process.

The purpose of the workshops was to create a common space for the Living Lab stakeholders to critically reflect on their experiences with the implementation and directly share the matter-of-fact assessment of their hands-on experiences. As an end result, the workshops contributed to the elaboration of more specific evaluation questions about the methodology and process of the implementation.

-

2.

The in-depth evaluation questions were asked from the so-called Lab Managers, the key people responsible for the planning, coordination and facilitation of the Living Lab implementation process. Their responsibility ranged from implementing and monitoring all stages of the process through recruiting, engaging and supporting all relevant internal and external stakeholders to communicating and reporting to the organisational and project management.

Late October and early November 2022 the Lab Managers answered the questions in the form of an online self-evaluation questionnaire developed by ARC Fund. They had to give short but concise answer to a variety of questions introducing their organisation, explaining the reasons for their commitment to adopt institutional changes, and going into detail about the actual measures undertaken, also highlighting the participating internal and external stakeholders, as well as the barriers, drivers, good practices and potential sustainability of the induced changes.

-

3.

Building on the responses of the Lab Managers, a 2-day workshop dedicated for knowledge and experience transfer was organised by ARC Fund at the end of November 2022. On the first day the lessons and experiences of the six implementation cases were discussed in detail with the involvement of external experts, and on the second day a final evaluative workshop was organised under the guidance of ZSI on the emerging challenges and potential sustainable outcomes of the Living Labs.

This workshop was the first opportunity to bring together, in one physical location, all Living Lab implementers to discuss and rank the barriers to the implementation of the elaborated RRI governance system within organisations and the measures to react to them.

The work was done in break-out sessions with facilitators where one group included the Lab Managers, while two other break-out sessions involved the other internal and external Living Lab stakeholders to discuss the key enabling external factors (drivers) and the actions and strategies that could exercise an either positive or negative impact for RRI institutionalisation. After the end of the parallel break-out sessions the group work was discussed in a plenary setting involving all participants to draw conclusions and make recommendations.

3.1 Lessons Learnt from the Living Labs

By resorting to the drawn-up methodological framework dividing the six implementer organisations to three categories (quadrants) in respect of readiness for RRI institutionalisation we are able to put the evaluation results to a broader context and describe the specific organisational circumstances and characteristics relating to the identified drivers and barriers.

Each organisation has made a self-assessment in terms of the RRI institutionalisation quadrants at the second phase of the Living Lab evaluation (online questionnaire). UJI and Harno have indicated to belong to the ‘strong leadership, strong base’ category. UNINOVA and ESPAITEC were classified to the ‘strong leadership, weak base’ category. ARC Fund confirmed to have a strong base but a weak leadership. NTNU could not decide on a specific category but upon further investigation we have added the institution to the same category (For a longer description of Harno, UNINOVA, and UJI cases see, respectively, chapters 5, 6 and 7 in this same volume).

We add this additional layer of organisational diversity to the already established three types of RRI governance perspectives, i.e., the structural, cultural and interchange aspects to summarise our findings as follows:

In the ‘ideal’ scenario when there is both a supportive management and already established support structures and practices for RRI institutionalisation, many barriers have already been removed. Most importantly, the dedication of the management means a favourable position in getting the necessary extra funding and experts needed for RRI institutionalisation within the organisation. Managerial support and the previous good experience gained with RRI practices also increase the chances of a successful cooperation of internal and external stakeholders across several disciplines.

While structural barriers have lost their relevance in this case, cultural barriers might still need to be overcome: the theoretical support expressed by stakeholders should be turned into an active commitment with concrete contributions. In addition to a heavy workload, this reluctance might stem from a lack of knowledge and understanding of the complex RRI concept sometimes perceived as mandated by external parties.

Cultural drivers might help counteract such attitudes, aiming to embed RRI into organisational (soft) values and identity. A participatory and collaborative process was used to set up a truly open debate space to discuss how to achieve this goal. Such a process could benefit from a neutral organisational facilitator and definitely should involve external stakeholders.

In the concrete Living Lab implementation cases such a process consisted of an initial consultation and interviews about the knowledge of various RRI keys, internal working groups meetings, bilateral meetings and workshops with external stakeholders, also seeking synergies with broader initiatives of interests within the organisation.

The successful implementation of such open participatory processes is in itself a success but the Living Labs managed to adopt new codes of ethics and good practices in this short timeframe. Particularly important was the addition of a glossary of complex RRI concepts into the code drafted by UJI, which proved to be very useful for the interested research community. Such novel outcomes contribute to the dedicated objective of these Living Lab implementers to strengthen their frontrunner position in RRI and be recognised for this level of excellence (a cultural driver).

Living Labs with a committed (higher-level) management but a weak base were in a special situation because they are not ‘traditional’ RPOs: UNINOVA’s researchers are employees of other institutions and therefore subject to the host organisations’ RRI governance systems (in this sense UNINOVA can be seen as a federated ecosystem of researchers), while ESPAITEC is a science and technology park acting as a facilitator among all the innovation ecosystem agents (start-ups, spin-offs, entrepreneurs and university researchers).

Hence managers aimed to focus on complementary RRI aspects perceived as the most important or the most feasible to implement (e.g., gender in case of ESPAITEC). The managers wanted to promote excellent research and innovation practices to ‘change the organisational culture’ but were also motivated by interchange-related drivers, e.g., to comply with the contractual obligations towards the national research funding agency in terms of RRI.

As a first step, a knowledge pooling exercise was conducted to identify the achievable goals and priorities by recognising the weaknesses to overcome, the already available RRI knowledge and skills, and the best methods to adopt elements of RRI governance in a sustainable way.

Similar to Living Labs with a strong base and leadership, the scarce time available for researchers to spend on RRI issues proved a major barrier. To increase the awareness, understanding and motivation of researchers towards RRI institutionalisation, organisational ‘facilitators’ (a small but dedicated RRI team or external experts) planned a participatory process with as few formalities as possible to consult, refine and adopt practical RRI documents that also adapted RRI jargon to institutional reality. An important aspect is that external stakeholders were involved in this process through working sessions to offer valuable ideas, feedback and networking opportunities for an effective RRI institutionalisation.

The participatory process resulted in drafting key documents on various RRI aspects and in case of UNINOVA was complemented by actions with the aim to change organisational culture, such as a specific website section to raise awareness on RRI, or training sessions on RRI organised for young researchers and PhD students of the institute.

The implementation process progressed with the most difficulties in Living Labs where – opposite to the above-described scenario – the existing base was strong but leadership support was ambivalent or remained declarative in nature.

In both cases the base was strong: there were clear organisational mandates to conduct research in an ethical way, for the public benefit and support structures were already in place in the form of various documents and (advisory) bodies (even though scattered around in different departments or not explicitly referring to RRI). The researchers in both organisations were also quite well-versed in and motivated to deal with RRI or ethical issues, based on their disciplinary or project-related experience and professional interests. External drivers such as the requirement of funding programmes might have also played a facilitating role for RRI uptake.

Nevertheless, key structural barriers prevented these Living Labs from achieving tangible results in the relatively short implementation timeframe defined by the project. The usual culprit of lack of time and personnel available for RRI institutionalisation was worsened by the indecisive support and engagement rendered by (higher-level) senior managers. Thus, even the initial decision on the proper implementation level and planning caused unwanted delays. This was connected with the issue of size: NTNU is too big for a Living Lab and thus looked for a suitable department for implementation, while ARC Fund is too small and has very different foci around three thematic programmes (but in the end used RRI as a common frame).

The ambivalent support did not help convince the relevant stakeholders of the benefits of RRI institutionalisation: there was a general feeling among some researchers that this is an externally mandated process which aims to discuss again topics that have already been discussed and/or do not need solutions. The size of implementers played again a role here in different ways: the small team of ARC Fund researchers felt a sense of ‘fatigue’ towards the topics already encountered several times in many RRI-projects and NTNU has already possessed of similar RRI governance structures but at an organisational (not departmental) level.

In short, initial structural barriers exacerbated cultural barriers in turn. To remedy the situation a participatory process for RRI institutionalisation started but progressed slowly or were stuck in key moments. This process in both organisations successfully managed to assess the RRI-related situation, and identify important RRI aspects worthy of further discussion or endorsement but concrete supporting documents or bodies have not been adopted yet. The main tool used was different types of internal reflection spaces, such as semi-structured interviews, workshops and focus groups, however the engagement of external stakeholders was deemed problematic.

4 Conclusions

The ‘post-pilot’ evaluation confirmed the validity of some of the key findings of the ‘pre-pilot evaluation’, meaning that certain incentive factors and barriers need to be considered in specific organisational circumstances to ensure a successful organisational adoption and use of RRI.

Strong leadership, i.e., the active engagement and support of the higher-level management seems to be the most significant driver without which a genuine RRI institutionalisation is doomed to fail or at least progress slowly. If other key structural drivers are available, e.g., support structures (‘base’) and adherent organisational mandates, the RRI institutionalisation can progress steadily with the aim of introducing substantial changes in all RRI keys.

The existence of such supporting structure also stemming from bottom-up initiatives are particularly important for sustainability because it is true that the implementation may start as a top-down approach (even forced by external requirements e.g. from funding bodies), but its long-term impact ultimately relies on the bottom-up approach guaranteeing appreciation and motivation of relevant stakeholders.

This bottom-up approach is manifested in the co-creation process which lies at the heart of Living Labs aiming to reform the ‘business-as-usual’ approach to research in organisations. Co-creation can be in itself a challenge; e.g. regarding the involvement of external stakeholders, with which more implementers struggled – but it is also a rewarding endeavour where internal and external stakeholders from many disciplines participate in enriching discussions in various reflection spaces to improve the quality and relevance of the achieved results.

Co-creation is time and resource-intensive which is another barrier to take care of early on. In order to plan for feasible results with the available resources, Living Labs should start with the understanding of the broader (country) and local (organisational) context, i.e. available funding, personnel, time, prevailing and missing RRI aspects, the perspective and needs of stakeholders, preferably done by organisational ‘facilitators’ (proactive and committed employees with experience in RRI).

Living labs are context-bound, there are no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions but goals and actions should be aligned with national and institutional reality. The methodology developed in the project is considered to provide good ideas and inspiration but each organisation should develop its own path towards RRI-paved institutional change.

The results show that substantial RRI-related changes in such a short time frame could only be achieved by larger RPOs and RFOs that have already had a strong leadership and base (e.g., UJI, Harno). Implementers with no strong leadership but with a formidable base could only use this time for self-reflection and a better understanding of their situation. Implementers with no base but an engaged management could go one step further and look for complementarities, i.e., adopting RRI aspects perceived as the most important to the organisation, subsequently benefitting the use of other RRI keys.

While the long-term goal of all such Living Labs should be the change of culture, the impact of seemingly small-scale changes should not be underestimated. A shift in organisational culture might be achieved exactly by such actions, e.g., hands-on guides with an understandable terminology, awards given for considerable RRI-related achievements or practical training on various RRI aspects, changing the RRI-related attitudes and mindset of the next generations.

Such an incremental approach is not only beneficial due to the high variety in institutional settings but also because many barriers are interconnected and reinforcing. Living Labs should use a flexible and adaptable approach to find the right intervention points to tackle the RRI-related issues deemed most relevant by stakeholders with the appropriate measures available within the context-dependent conditions. Thus, the RRI institutionalisation process will not be seen as a ‘straitjacket’ but rather as an opportunity.

Notes

- 1.

Titled ETHNA System, a concept that was finalised under the guidance of the project coordinator Jaume I University (UJI), more details on the specific content of the system can be found in [2].

- 2.

See results at: https://zenodo.org/record/6616553#.ZBmaKXbMI2x.

- 3.

December 2022 - March 2023.

- 4.

More information on the format and results of the participatory evaluative workshops is available here: Alves, Elsa (2022). D5.4 Report on the ETHNA System Implementation Analysis & Alves, Elsa (2022). D5.5 Report on the difficulties found in the implementation processes. https://ethnasystem.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/5.5-Report-collecting-the-difficulties-found-in-the-implementation-processes-final_181222.pdf

References

Steen, M., Nauta, J., Gaasterland, R., Ogier, S.: Institutionalizing responsible research and innovation: case studies. In: Bitran, I., Conn, S., Huizingh, E., Kokshagina, O., Torkkeli, M., Tynnhammar, M. (eds.) Proceedings of the XXIX ISPIM Innovation Conference: Innovation, The Name of the Game (2018) ISPIM

González-Esteban, E.: The ETHNA system and support tools. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, Springer, Cham (2023)

Evans, P., Schuurman, D., Ståhlbröst, A., Vervoort, K.: Living Lab Methodology Handbook. European Network of Living Labs (2017). https://issuu.com/enoll/docs/366265932-u4iot-LivingLabmethodology-handbook. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Häberlein, L., Mönig, J.M., Hövel, P.: Mapping stakeholders and scoping involvement – a guide for HEFRCs. Project Deliverable, Ethics Governance System for RRI in Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres (2021). https://ethnasystem.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ETHNA_2021_d3.1-stakeholdermapping_2110011.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Popa, E., Blok, V., Wesselink, R.: Social Labs for Quadruple Helix Collaborations – A manual for designing and implementing social Labs in collaboration between industry, academia, policy and citizen. Project Deliverable, RiConfigure (2018). http://riconfigure.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/D01.2_Social-Lab-Methodology-Manual_v2.0.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Forsberg, E.-M., Ladikas, M.: Analytic framework and case study protocol. Project Deliverable, RRI-Practice (2017). https://www.rri-practice.eu/knowledge-repository/publications-and-deliverables. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Wittrock, C., Forsberg, E.-M., Pols, A., Macnaghten, P., Ludwig, D.: Introduction to RRI and the organisational study. In: Implementing Responsible Research and Innovation. SE, pp. 7–22. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54286-3_2

Szüdi, G., Lampert, D.: Blueprint for institutional change to implement an effective RRI governance. Project Deliverable, Ethics Governance System for RRI in Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7730729

González-Esteban, E., Feenstra, R., Calvo, P., Sanahuja, R., Fernández-Beltrán, F., García-Marzá, D.: Draft concept of the ETHNA System, Project Deliverable, Ethics Governance System for RRI in Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres (2021). https://ethnasystem.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/D4.2_ETHNA_final-concept.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Bernal-Sánchez, L., Feenstra, R.A.: Developing RRI and Research Ethics at University. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, volume 13875, Springer, Cham (2023)

Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Ferrada, F., Oliveira, A.I.: Implementing RRI in a research and innovation ecosystem. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, volume 13875, Springer, Cham (2023)

Hajdinjak, M.: Implementing RRI in a Non-Governmental Research Institute. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, volume 13875, Springer, Cham (2023)

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the European Project “Ethics Governance System for RRI in Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres” [872360], funded by the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Commission. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Szüdi, G., Lampert, D., Hajdinjak, M., Asenova, D., Alves, E., Bidstrup, M.V. (2023). Evaluation of RRI Institutionalisation Endeavours: Specificities, Drivers, Barriers, and Good Practices Based on a Multi-stakeholder Consultation and Living Lab Experiences. In: González-Esteban, E., Feenstra, R.A., Camarinha-Matos, L.M. (eds) Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13875. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33177-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33177-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33176-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33177-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)