Abstract

The article deals with ethics governance systems in the field of research and innovation at the organisational level, both for organisations performing and funding research and innovation activities. In particular, it proposes and argues for a system called ETHNA System. Informed by a deliberative and participatory concept of ethics governance, as well as by the dimensions of responsibility in research and innovation – anticipation, inclusion, reflection and responsiveness – it proposes a modular design of ethics governance based on four mechanisms: a responsible research and innovation (RRI) Office(r); a Code of Ethics and Good Practices in research and innovation (R&I); an ethics committee on R&I and an ethics line. Moreover, to ensure continuous improvement, a system for monitoring the process and the achievement of results is provided. The system also offers specific details of the implementation process paying attention to four issues: research integrity, gender perspective, open access and public engagement.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- ethics governance

- responsible research

- university

- RRI Office (r)

- Code of Ethics and Good Practices

- Ethics Committee

- Ethical Line

- monitoring indicators

1 Introduction

The ETHNA System (Ethics Governance System for Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) in Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres) has been designed as a governance system that enables the ethical self-regulation of the research activity. It has been designed as a governance structure which should be ethical and effective at the organisational level.

The ETHNA System consists of a foundation block (an ETHNA Office or Officer) and three column blocks (or ethical tools) with a monitoring block. Together, these blocks align the spaces of research and innovation with the highest ethical standards of RRI.

Competences of the ETHNA System are linked to the R&I space of the university institution, promoting good practices aligned with the values, needs and expectations of their internal and external stakeholders. Its main responsibility is to promote ethical responsibility through self-regulation, while following the current legislative framework, but without resulting in a new bureaucratic compliance process [1].

The ETHNA System addresses a commitment that goes beyond professional self-regulation in the area of research ethics, demanding the self-regulation of the organisations that carry out or fund R&I so that they live up to ethical standards and to society’s needs and expectations while respecting the existing legislative framework. As several authors point out, “self-regulation and behavioural norms within research communities alone have not prevented all sorts of fraudulent behaviour in research” [2] so the presence of structures in these organisations that will ensure a culture and environment inclined towards ethical excellence is necessary in the 21st century. In Chapter 1 of this book [3], it has already been argued that this system follows a meta-governance model that implies the governance of self-regulation.

As will be seen in the following sections, this proposal for the governance of self-regulation of processes and practices in Research Performing Organisations (RPO’s) and Research Funding Organisations (RFO’s) is informed by a deliberative and participatory concept of responsibility and the governance of research. In morally pluralistic societies it is necessary to discover what values, principles and good practices could be accepted as correct or just, as there are no closed lists or unique codes to attend to. On the one hand, in these morally pluralistic contexts, discursive processes are required to facilitate the inclusion of those affected (in the present and the future) when determining the shared values and principles. On the other hand, given the complex organisations, as well as deliberating when there are conflicts of interest [4, 5]. The proposed system and its accompanying elements have been designed using this co-creation methodology, based on living-labs that have involved the participation of internal and external stakeholders (see [6,7,8,9]).

2 The “Ethics Governance” Concept that Informs the ETHNA System

Science and Technology Studies (STS) have given a good account of the shift in governance from self-regulation to external regulation in the late 1970s and 1980s. This includes a shift of who advises on governance: “First, those with scientific, technological expertise, with their input being guided by legal expertise; second, those with ‘ethic-legal’ expertise; and third, those included as part of ‘public participation’” [10]. At that time, three styles of science and technology governance were present.

In the “technocratic” style of governance, a specific format for decision-making is dominant. This style implies two aspects of technical regulations: scientists and technologists as assessors of acceptable risk; law and lawyers as framers of governance procedures in order to, for example, make suggestions for changes to legal frameworks, self-regulation or new regulations.

In the “applied ethics” style of governance, the ensuing approaches were based on input from ethical experts from the fields of applied ethics and bioethics, as well as socially engaged scientists with specific experience and interest in ethical issues related to science and technology. Ethics in the governance of science and technology arguably has an influence in an advisory capacity on the moral issues that are intrinsically connected to science and technology, but also as a mediator regarding the outline of debate platforms in terms of the triple helix of transparency, democracy and trust.

In the “public participation” style of governance, from the late 1970s onwards, more proactive approaches to governance were developed to directly involve citizens in decision-making on science and technology, be it for surveying public opinion, consultation, or direct democratic decision-making. These included citizen juries, citizen panels, consensus conferences, planning cells, deliberative polling, focus groups, consensus building exercises, surveys, public hearings, open houses, citizen advisory committees, community planning and referenda [10].

Landeweerd et al. [10] argued that RRI fitted in with the idea of moving from “governing” to “governance”; rather than locating the authority of decision at the policy-making level, governance aimed to embed decision-making processes into practice itself. Where the public and or citizen participation is the key.

The foreseen perils were that this framework would potentially damage not only the autonomy of the expert communities involved, but also the sovereignty of the public bodies (politicians, policy-makers) that ought to guarantee the public legitimacy of the choices made. In this case, although cooperation between public and private may seem to enhance the embedding of R&I in society, it may actually render public funding and public interest sub-service to private interests. Increasing the extent to which these interests serve both public and private goals may be a positive development, but does not mean that a voice for public interest is no longer needed. According to Landeweerd and colleagues [10], RRI can only be successful if it develops strategies to prevent publicly delegated sovereignty from eroding.

There are several implications to consider in an ethics governance system of RRI in the RPO’s and RFO’s. First, approaches to governance need to move beyond the idea of governance as “quick fixes” to ethical issues of science and technology. It needs to be acknowledged that nothing is clear-cut or well-defined. Not only is there a complexity of problems and uncertainty scenarios, but also a kaleidoscope of ethical, social, legal and technical issues requiring reflection and multidisciplinary work. Second, “acknowledging complexity means that governance should be less about defining clear-cut solutions and more about making explicit the political issues that are at stake in science and technology” along with the ethical issues that require inclusion and open deliberation. Third, new more hybrid styles of governance emerge, in which the role of expert knowledge is explicitly acknowledged, but the range of relevant forms of expertise broadens [10].

2.1 Toward Discursive Ethics Governance

The governance of science and technology is dominated by a risk-safety-and precaution discourse. Responsibility in governance has historically been concerned with “products” of science and innovation, in particular impacts that later become unacceptable or harmful to society or the environment. This approach doesn’t encourage debate and reflection on frameworks for justice, welfare standards for marginalised groups, politics of exclusion, privacy, etc. Its responsibility approach is retrospective, to use the terminology used in [3, 10, 11].

This ethical paradigm suggests that conceptions of responsibility should build on the understanding that science and technology are not only technical, but also social, political and ethical. In this vein, governance processes also imply identifying “in advance many of the most profound impacts that we have experienced through innovation” [11]. Debate and controversies often surround science and technology and should be involved in governance. As Stilgoe and colleagues [11] argue “Such controversies have demonstrated that public concerns cannot be reduced to questions of risk, but rather encompass a range of concerns relating to the purposes and motivations of research, joining a stream of policy debate about the directions of innovation. Yet, despite efforts at enlarging participation, current forms of regulatory governance offer little scope for broad ethical reflection on the purposes of science or innovation” [12]. This paradigm thus points to a prospective or forward-looking conception of responsibility where procedural ethics plays a relevant role.

The literature review argues that the consequentialist model of the ethics governance of research and innovation should move toward another model. Dissatisfaction with “risk-based regulation has moved attention away from accountability, liability and evidence toward those future-oriented dimensions of responsibility – care and responsiveness – that offer greater potential to accommodate uncertainty and allow reflection on purposes and values” [11, 13, 14].

The discourse that emerged from the European Commission (EC) at the start of the past decade used this ethics governance to focus on aligning R&I to the values, needs and expectations of society, and to move toward an ethical paradigm of the governance of science and innovation. It is an approach that is making great progress but still evolving, in what is now being called Open Science, but maintaining the requirements of RRI [15, 16].

In this approach, the EC attempts to strongly emphasise “societal grand challenges” that have been defined as six keys or the policy agenda. The problem today is, as many authors show in the literature on RRI [17], that for the EC these keys are used as the RRI framework and not as challenges that the RRI framework should tackle.

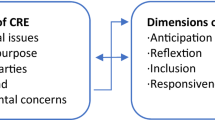

The ETHNA System considers that the ethics governance of the RRI model should be designed in the RPO’s and RFO’s, such as universities, technological parks, innovation centres, etc., to provide an answer to the four dimensions of the RRI process (anticipation, inclusion, reflection and responsiveness) in which the six keys or the policy agenda will be issues or societal grand challenges. These issues or keys do not constitute all the aspects to be addressed by a RPO or RFO, but the political agenda has identified them as relevant demands and social requirements for which knowledge has begun to be mobilised and the European research space has begun to be transformed around. RPO’s and RFO’s must therefore consider themselves open to other topics that may be relevant in their social or community environment. When faced with these, research centres should institutionalise anticipation, inclusion, reflection, and action processes.

2.2 Discourse Ethical Paradigm: RRI as a New Social Contract

RRI is the reflection of a new social contract between science, innovation and society in general [18] which involves a change in the division of moral labour in R&I [19] aimed primarily at research governance [20]. As Stahl remarks, “RRI is concerned with creating a new mode of research governance that can transform existing processes with a view to ensuring a greater acceptability and even desirability of novel research and innovation outcomes” [21]. Von Schomberg stresses that the product and process dimensions are naturally interrelated. Where “products should be evaluated and designed with a view to these normative anchor points: with a high level of protection to the environment and human health, sustainability, and societal desirability” and where the challenge of the process dimension “is to arrive at a more responsive, adaptative, and integrated management of the innovation process” [14].

Until the mid-20th century, the social contract implied “freedom, social licence and funding to invent, innovate and pursue scientific endeavours” that have been exchanged for the promise, and sometimes expectation, of knowledge, understanding, and value (economic, social or otherwise). By including the expectations that existing norms, laws and standards of conduct are adhered to, there is a long-standing history of responsibility in the research integrity context in this regard. This contract has been re-evaluated, especially for the often unintended and unforeseen impacts [21], and to form complex interactions with, and transformative consequences for, society. This is a symptom of what Hans Jonas described as the “altered nature of human action”, mediated through technology and innovation [13].

2.3 Models or Mechanisms to be Used to Manage this New Social Contract

The literature categorises them as two main models: Old models of governance characterised by being centralised and having a regulatory centre; modern models whose central feature is that they are decentralised, with open-ended governance and soft governance, operating in new places: markets, networks and partnerships, as well as conventional policy and politics [11, 22]. These new models include multi-level, non-regulatory forms of science and innovation governance combined with old models. There is a combination and complementation with policy instruments such as normative codes of conduct, standards, certifications and accreditations that run alongside expert reports, technology assessments and strategic roadmaps. They have attempted to open up science and innovation to a wider range of inputs, notably by creating new spaces of “public dialogue” [12, 23, 24].

As Stilgoe et al. explain [11], the conventional model focuses on technological product questions meanwhile ethics governance and research integrity move into processes and autonomy and well-being of human volunteers and animals involved in experimentation. The new social contract is in the uncertainty scope. It moves in a scenario where the answers are not given, they are open and have to be defined.

The limitations of the old models of governance to responsibility is evident especially if we focus on R&I because regulatory and governance forms do not exist in this area. Then the key question is how to build a democratic governance mechanism of the intention without biasing the innovation process at the beginning of the procedure, in line with the previous section.

The answer is an ethics governance of RRI that ought to be democratically inclusive. That is to say, RRI that will reflect on its intentions and will be aware of the future that we want and that concerns us, whose challenges we wish to face. And this kind of RRI should respond to a mixed ethics governance model where the value-oriented and culture approach of self-governance will take pre-eminence over the compliance or regulatory approach [25]. The implementation of RRI activities through research governance measures can employ widely shared principles of research governance, such as the integration of democratic principles into research, the precautionary principle, the principle of regulatory parsimony [20] and the discourse ethics principle [26].

In our understanding, the ETHNA System is a suitable option to shift research performance towards ethics governance using the modern governance style. Following this ethics governance relevant organisations will adopt RRI as a component of their strategic framework and will aim to ensure all R&I activities cover all (or most) RRI components: the dimensions and key issues or areas. From this point of view, ethics governance of RRI is not just about compliance and a centralised model. It is about a set of aspirations related to a continuing commitment to be proactive, inclusive, reflexive and responsive with the ethical challenges that R&I has to face. Then ethics governance of RRI in RPO’s and RFO’s should pre-eminently be a deliberately decentralised self-governance model.

3 A Model for the Ethical Self-regulation of Research for Universities Based on the RRI Framework: Generating Open Science

The key issue is addressing the ethical concept lying beneath RRI and its institutionalisation through a government system. It is an ethical concept that needs a critical meaning, and not merely a conventional one. We will then be able to take account of both backward-looking and forward-looking responsibility [27]. It is also necessary to design ethical management systems of RRI dimensions (anticipation, inclusion, reflection, responsiveness) in institutions and organisations that can provide answers in key areas (integrity research, gender perspective, open access, public engagement, among others) when organisations generate or fund R&I [28, 29].

RRI emerged in Europe and was driven by European institutions. The ELSA (Ethical, Legal and Social Aspects of Emerging Sciences and Technologies) framework was the forerunner of the current concept. Initially, the aim was to lay down some guidelines in the research used as regulatory frameworks to be considered in developing European R&I [17, 19, 30, 31].

In 2011, in an expert group context, the European Union (EU) presented the RRI concept, defined in 2012 as follows: “Responsible Research and Innovation means that societal actors work together during the whole research and innovation process in order to better align both the process and its outcomes, with the values, needs and expectations of European society. RRI is an ambitious challenge for the creation of a Research and Innovation policy driven by the needs of society and engaging all societal actors via inclusive participatory approaches” [32].

This definition catches up a new approach in the RRI concept driven by the EU since 2011, that has been an “anticipatory governance”, a guideline for R&I activity. Anticipatory governance aims to create a research atmosphere in which all present and future scenarios that can help to minimise possible risks to decision-making by providing feasible alternatives can be highlighted. Moreover, the integration of social science and humanist perspectives is important as a control, and also because it creates opportunities for dialogue and more reflexive decision-making [33, 34]. Additionally, this “anticipatory governance” entails a “democratic governance” that promotes interaction among the several agents integrating heterogeneous values, concerns, intentions and purposes [35]. The underlying idea is that research and innovation need to be democratised and must engage with the public to serve the public [14, 36].

RRI becomes an EU requirement so that the scientific community and society can work together to make the processes and results of science respond not only to the expectations, values and reflection of researchers, but also to those of citizens [29]. RRI can therefore be claimed to be a concept that comes from EU scientific legislators and institutions in a top-down process [29, 37]. However, at the same time, the RRI concept and its implied practice are also a bottom-up process in which existing experiences should be taken into account, as well as encouraging mutual learning [38].

It should be noted that some studies show how researchers and the scientific community recognise RRI traits and identify responsible R&I features with the same relevant issues [39]. Yet, at the same time, these scientists affirm that some practical barriers hinder RRI which could be tackled with a range of strategies at different levels. Recent studies have shown that: “These constraints included barriers likened to time, funding, reward systems, training, expectations of scientific production and the moral division of labour” where some are at an individual level but others are institutional [39].

As noted, the ETHNA System has been designed to be a way how RRI practices can be taken root in organisations that fund or carry out R&I. The aim is to drive ethical R&I using the double loop of “top-down” and “bottom-down” processes and, in parallel, as a means to overcome some obstacles for RRI and to promote it. The ETHNA System attempts to do so by working at an institutional level to promote RRI at an individual level, as both levels are interrelated or intertwined.

3.1 Three Complementary Discourses Behind the RRI Framework

The RRI concept then arises as a path to three discourses: democratic governance, responsiveness and responsibility that arises [12, 15, 16, 40]. The first discourse emphasises the democratic governance of R&I purposes and their orientation towards the “right impacts”. Discourse on democratic governance is linked to reflection on the purposes and motivations for the products of science and innovation made in accordance with democratic governance. The RRI discourse asks “how the targets for innovation can be identified in an ethical, inclusive, democratic and equitable manner” [40]. Its purpose is therefore to democratically open up and materialise new areas of public value for science and innovation where the principle of participation plays an important role. The early definition shows the need to share values in which R&I are anchored. Then the next question is “What are the ‘right impacts’ of R&I?”, and what values should these be anchored to?” [41, 42]. As previously mentioned, there are several proposals as to where the correct impacts can be defined (European Treaty, Human Rights Declaration, SDG among others), as well as different methodologies to be able to recognise them.

The second discourse focuses on responsiveness by emphasising the integration and institutionalisation of established approaches of anticipation, reflection and deliberation in and around R&I, influencing their direction and the associated policies.

Discourse on responsiveness involves reflection on R&I consequences and implications, intended and unintended impacts – anticipation, reflection and inclusive deliberation – on policy- and decision-making processes. It leads to the integration and institutionalisation of established mechanisms of reflection, anticipation and inclusive deliberation in and around R&I processes. And this reflection should be made on underlying purposes, motivations and potential impacts, what is known and what is not known, associated uncertainties, risks, areas of ignorance, assumptions, questions and (ethical) dilemmas. There is a need to inclusively open up such reflection to broad, collective deliberation through processes of dialogue, engagement and debate by inviting and listening to wider perspectives from public and diverse stakeholders. Thus, RRI is concerned with the democratic governance of intent.

The third area concerns the framing of responsibility itself within the R&I context as collective activities with uncertain and unpredictable consequences. There are different subjects with responsibility: scientists, universities, innovators, businesses, policy-makers and research funders. Funders play a leadership role in establishing a framework for RRI, but they must also lead by example. Consequentialist models of responsibility are problematic when we analyse the responsibility of innovation. In this context, other categories have been proposed as being more appropriate, such as care or responsiveness [18, 40], the definition of positive benefits or right impacts [14] and the legitimate interests of those affected [26, 43].

3.2 Procedural Ethics Governance with Four Dimensions for Approaching Ethical and Social Demands

In this section we look at the transition from theoretical to practical frameworks. That is, from the why to the how with a RRI operationalized. The ETHNA System has been designed to generate organisational processes that encourage responsible R&I following the RRI framework proposed by Owen, Stahl and Stilgoe, thus “entailing an ongoing commitment to be anticipatory, reflective, inclusively deliberative and responsive” [18]. Based on these institutionalised processes in RPO’s and RFO’s and using the building blocks, it is proposed to create the agenda of issues to be addressed and to which a response must be given in order to meet society’s demands and requirements and to involve it in the very process of creating research and innovation. Specifically, the ETHNA System proposes the topics of integrity, gender, open access and public engagement, because it is necessary to begin by thematising aspects to be covered within the ethics governance system. And these issues have received much more attention in the European Union’s research space, marked by the agendas of scientific policy and society. But, as has been pointed out, these issues were initially considered but there is room for identifying and dealing with further issues also based on stakeholder dialogue.

These four dimensions are not entirely new as they have their own background and roots. However, what is new in the RRI framework is that they can be used theoretically and practically as a procedural framework to guide R&I under conditions of uncertainty and ignorance. Moreover, “this redrawing will need to be done in a way that allows the constructive and democratic stewardship of science and innovation in the face of uncertainty toward futures we agree are both acceptable and desirable: this is a collective responsibility” [18]. The four dimensions of RRI could be described as a methodological process that implies their interrelation. The following is a brief account of these four dimensions and how they are covered by the ETHNA System [11, 18].

Anticipation [anticipatory].

This focuses on describing and analysing the intended and potentially unintended impacts that might arise whether they be economic, social, environmental, or otherwise. It is supported by methodologies that include foresight, technology assessment and scenario development, among others. The anticipation method has been used to design the ETHNA System itself, holding panels with experts concerning both ethical and RRI governance, as well as stakeholders from inside and outside the research practice. It is also proposed as one of the processes to be strengthened within good practices in research, within the Code of Ethics and Good Practices.

Inclusion [deliberative and engaging].

This aims to inclusively open up visions, purposes, questions and dilemmas to broad collective deliberation through processes of dialogue, engagement and debate by inviting and listening to wider perspectives from public and diverse stakeholders. This is a part of a search for legitimacy and for generating trust in science [44]. This could include small-group processes for public dialogue: consensus conferences, citizens’ juries, deliberative mapping, deliberative polling and focus groups. Inclusion and deliberation are argued as a “moral obligation” to identify the desirable outcomes of science and technology for society [45], and also as a way to accommodate new claims in discourse [46, 47]. Here we find important critics on effectiveness and its benefits. While there has been resistance shown to attempts to proceduralise public dialogue for fear that it becomes another means of closure or technocracy, efforts have been made to develop criteria that aim to assess the quality of dialogue as a learning exercise (see [6]).

Reflection [reflective].

This consists of reflecting on underlying purposes, motivations and potential impacts; what is known (including areas of regulation, ethical review, or other forms of governance that may exist) and what is not known; associated uncertainties, risks, areas of ignorance, assumptions, questions and dilemmas. There is a demonstrated need for institutional reflection in governance [26, 48]. The ETHNA System endorses four mechanisms designed to promote reflection through dialogue: the Code of Ethics and Good Practices in R&I, Ethics Committee on R&I and the Ethics Line. With this structure, RPO’s and RFO’s are promoting the adoption of standards, and may build this second-order reflection by drawing connections between external value systems and scientific practice [49].

Responsiveness [responsive or active].

This should be an iterative, inclusive and open process of adaptive learning with a dynamic capability. Responsible innovation requires the capacity to change shape or direction in response to stakeholder and public values, and changing circumstances. In order to generate ethics governance of research in RPOs and RFOs that respond to this dimension, the ETHNA System proposes to monitor the construction of governance structures (RRI Office(r), Code of Ethics and Good Practices, ethics committee on R&I, ethics line) with indicators of progress and performance. With its structures, it also establishes the processes for responding to the expectations and values that a RPO or RFO is expected to meet. On the one hand, it means to respond and, on the other hand, it means to react and to answer.

The ETHNA System is coherent with the procedural dimensions described [50]. Achieving this depends on scientific awareness, as well as on continuous and iterative processes that require the institutionalisation of governance [17].

3.3 Building an Open Agenda of Topics

The ETHNA System has been designed so that each RPO or RFO can address the issues that it considers an institutional priority. However, as a result of the collaboration within the European-wide Horizon 2020 project, not only has the design of the Ethics Governance processes been addressed, the aspects that could or should be covered have also been considered based on the four key points considered central by the RRI frameworks promoted by the EC. These are integrity research, gender perspective, open access and public engagement.

With its support tools, the ETHNA System offers an entry point to these issues that can be helpful for beginning deliberation and internal and external participation on how to define such issues, as well as thematising the demands that internal and external stakeholders are making towards RPO’s and RFO’s in order to trust their research, both as a process and as a result.

The outcomes regarding the issues are based on research carried out from 2020 to 2022 as part of the ETHNA System Project. This study involved a review of the scientific literature and previous European projects focused on RRI in different types of RPO’s and RFO’s, 23 in-depth interviews at European level with RRI and ethics governance experts, and a consultation based on semi-structured interviews and international workshops on different themes, as well as an online European survey covering internal and external stakeholders following the quadruple helix model [51]. The conceptualisation of these four issues after the study was defined as follows.

Research integrity is understood in the terms expressed by the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity [52], which notes integrity in a series of basic principles, such as honesty, reliability, responsibility and respect. These principles concern the entire research process, from the initial approach to its execution to its dissemination, bearing in mind that quality research cannot take place if it does not meet scientific integrity criteria. Aspects that were shown to be important included authorship in research (publications and patents), originality, peer review, conflicts of interest and collaborative working.

The gender perspective in research is understood to promote the gender perspective at organisational level and at researcher and individual level in terms of any policies the organisation may have to promote equality and potential good professional practices among its members. Without attempting an exhaustive list, the ETHNA System identifies some core issues that should help institutions improve governance in terms of effective equality between men and women, as well as aspects such encouraging the equal participation of men and women in research teams at all levels; including experts sensitive to gender balance in the assessment process for R&I funding projects; and rewarding gender-sensitive research and innovation in the configuration of teams when applying for funding.

Open access in research and innovation is defined based on the policies and good practices an organisation can develop in terms of research results, data management, administration, management of intellectual property rights, and patents. Here, hot topics include data management and administration, storage and preservation, and results protection management.

Finally, public engagement shows commitment to citizen science and to science open to participation and deliberation from its audiences from the beginning of the research design to the end, including development. In this sense, the essential issues are the processes for involving internal and external stakeholders particularly in research, taking into account the specific nature of vulnerable groups that may find it difficult to have a voice in research processes.

4 Description of the ETHNA System and Its Support Tools

This section presents a summary of the ETHNA System. First, it summarises the compass criteria that guide it and provide a basis for it, as well as the managerial principles that should guide its implementation in a RPO or RFO. Second, it shows that we are looking at a flexible system that starts from the material and leadership resources available to the organisation. Thus, the result of the implementation of the ethics governance system will take different forms, depending on how robust these two variables are in the organisation. Third, the three levels of commitment to which the organisation can adhere are presented. The process that backs the implementation of these levels is accompanied by support tools provided by the ETHNA System. Finally, the building blocks or basic ethics governance structures offered by the system are briefly described. Its implementation is understood based on the philosophy of continuous improvement.

4.1 Compass Criteria and Core Implementation Principles

The ETHNA System has two normative compass criteria that guide it and at the same time support it, and six managerial or pragmatic implementation criteria.

These two compass criteria guiding the ETHNA System are ethical and effective criteria. The ethical criterion, informed by Habermas’ theory of communicative action [53,54,55], provides a compass to qualify the governance structure, based on the “all-affected principle”, as more or less just. From the ethical foundation of this discourse, an ethics governance system is defined as one that promotes and facilitates (i) the inclusion of those immediately affected by it (i.e. R&I actors) in processes of discursive justification of the way in which the governance system is organised, and (ii) the inclusion of stakeholders (citizens, end-users, non-governmental organisations, business representatives, policy-makers) in processes of critical examination and discursive justification of possible scenarios and potential impacts generated by research and innovation processes. As can be seen, the ethical criterion is normatively based on the ETHNA System approach and, critically, on the four dimensions of RRI (anticipation, inclusion, reflection and responsiveness).

Moreover, the effective criteria, informed by governance theory on public innovation [56,57,58], refers to one that accommodates and facilitates the form that R&I activities often take, namely the form of networks. The networks are deliberative when defining the goals and objectives, highly autonomous in their working purpose and highly dynamic in their work processes.

The uptake of the flexible ethics governance ETHNA System compass by these two compass criteria needs core principles to help the implementation process. The core implementation principles that have been informed by the literature review and the process of interviews with experts that took place during the year 2020 following the “de facto governance” view are [19, 59]: flexibility, adaptability, integrity, responsiveness and proactivity, networking and directness. Briefly, these principles can be understood as follows in the ETHNA System:

-

Flexibility: the ETHNA System establishes a structure, protocol and an entry point and the organisation decides the level of commitment it wants to make to the ETHNA System.

-

Adaptability (evolvability): the ETHNA System provides a guide to define and engage the organisation’s stakeholders related to the R&I activities. The guide considers the plurality and diversity of the R&I ecosystem but not all the scenarios, so the ETHNA System should be adapted to each RPO or RFO.

-

Integrativity: the ETHNA System promotes the integration of the R&I initiatives, procedures and structures running in the organisation related to the RRI dimensions and keys or issues.

-

Responsiveness and proactiveness: the ETHNA System encourages the avoidance of bad practices or misconduct in R&I practices and relationships and promotes good practices.

-

Networking: the ETHNA System endorses networking following the Quadruple Helix Method (QHM) and sustained collaboration with its internal and external stakeholders.

-

Directness: the ETHNA System seeks to be direct and reduce the complexity a self-regulation system taking into account stakeholders and using the QHM could have.

4.2 An ETHNA System to be Built

As stated, the ETHNA System is a flexible ethics governance system that enables ethical self-regulation of the research activity at RPO’s or RFO’s. It has been designed as a meta-governance structure that is ethical and effective at an organisational level.

The ETHNA System offers four building blocks that incorporate a process for monitoring implementation and performance progress: a foundation block (RRI Office(r)) and three column blocks (Code of Ethics and Good Practices, Ethics Committee on R&I, Ethics Line). Together, these blocks align the research and innovation spaces with the highest ethical standards of RRI because they are designed to allow for anticipation, inclusion, reflection, and responsiveness in the institution's R&I space.

The procedural and formal structure of ETHNA System promotes the alignment of resources and processes already existing in the institutions, as well as the institutionalisation of new resources and processes, in order to implement a system of ethics governance of research (Fig. 1).

This shows a figure consisting of the different components of the ethics governance system (ETHNA System). Elements of the figure can be chosen and implemented in a flexible self-governance by RPO’s and RFO’s.

To further increase its adaptability, the ETHNA System regards two relevant factors as essential for the institutionalisation of RRI: the leadership, including the support it provides, on the one hand and the base on the other hand, i.e., the organisation’s research staff with their values, awareness, skills, knowledge, and practices already in place. The latter may vary, depending on the organisational unit and research or innovation field. Both axes need to become strong in the long run. For further information on those institutional factors and the adaptability provided by them in order to build the ETHNA System (see [60]).

4.3 Levels of Commitment to the ETHNA System and Support Tools to Achieve Them

Based on the analysis of the leadership and base, the organisation can also define its level of institutional commitment, depending on the capabilities and willingness of its leadership. The ETHNA System shows three levels of commitment, each one always incorporating a monitoring system with progress and performance indicators, which can be found in the support tools.

-

Level 1. The organisation appoints an RRI Office(r) and supports its activity. Moreover, the progress and performance indicators that monitor the institutionalisation of this building block are incorporated into the management governance.

-

Level 2. The organisation implements the RRI Office(r) or foundation block and some of the column blocks, incorporating one or more RRI keys or issues (research integrity, gender perspective, open access and or public engagement).

-

Level 3. The organisation designs and implements the RRI Office(r) and implements the three columns. The organisation applied a proactive attitude in all the RRI key areas: research integrity, gender perspective, open access, public engagement or any other area or issue that has been identified as a priority for the organisation after participation and deliberation with its stakeholders.

The ETHNA System offers, in open access, a set of support tools that make it easier for any organisation to make the appropriate decisions for the configuration of its personalised ethics governance system. These ready-to-use guides show, step by step, the decisions that the organisation should adopt so that each RPO or RFO builds its ethics governance system paying attention to its base and its leadership. The organisation with the support tools provides an example that can serve as an entry point for the institution to work through co-creation following the proposed ETHNA Lab methodology and designing its own. These examples are illustrated with good practices and examples that are the result of the experiences provided by experts and organisations that address ethics governance and RRI, either in their different dimensions or in the themes selected by the ETHNA System. It is therefore a starting point to be able to begin the path to reach the proposed level.

In short, ETHNA System offers any organisation a step-by-step Guide for the Implementation of the ETHNA System, as well as support tools [51].

4.4 The Building Blocks in a Monitored Continuous Improvement System

The fundamental objective of the basic structures and functions of these elements making up the organisation’s ethics governance of research, as understood in the ETHNA System, is given below. For space reasons, it is not possible to go into detail about each of these elements, nor was it possible to go into depth in Sect. 3.3. on the aspects that could be covered and that would provide the themes to be worked on with content. The following is a summary of some of the key points detailed in the public reports that can be found in the results of the ETHNA System project, which are openly accessible [51].

RRI Office (R)

The ETHNA Office is called the RRI Office or RRI Officer. This is because it may take the form of an administrative structure with an ethics officer as a leader who coordinates the tools (column blocks) and promotes the alignment of the existing resources by means of the ethics governance of research and innovation aligned with RRI. Although the existence of this role would be advisable, if it does not exist there is a need to establish who assumes these responsibilities – a possible option would be the ethics committee.

Having a formal Ethical Office of Research and Innovation with a high-level executive position leading an ethical infrastructure in an organisation would be very helpful in guiding professional and institutional moral performances [61]. The creation and maintenance of such structures will show a deep commitment to the promotion of ethical and responsible behaviour in research and innovation.

Code of Ethics and Good Practices in R&I

This is a self-regulatory document that explicitly outlines the principles, values, and good practices that should guide the activity of the people involved in R&I processes, as well as the organisation’s policies and programmes.

Ethics Committee on R&I

This is an internal consultation and arbitration body that acts as a forum for participation, reflection, and dialogue between the organisation’s different stakeholders on R&I matters.

Ethics Line

This is a communication channel that allows all stakeholders to easily and safely send the organisation suggestions, warnings, complaints, and reports.

ETHNA System has been designed as a continuous evolution system towards RRI. For this reason, it is recommended that the results measured by the indicators (progress and performance) and the adequacy of the indicators themselves have an annual or biannual review integrated into the RRI Action Plan. The RRI Office(r) will be responsible for reviewing these indicators and making progress visible, both internally and externally. This will allow the improvement of the construction, reinforcing both the base and the organisation’s leadership [51].

5 Summary and Final Remarks

ETHNA is a flexible ethics governance system designed to be implemented in RPOs and RFOs, in different contexts, i.e., universities, organisations funding research and innovation, research and development centres or innovation ecosystems. It follows two compass criteria: the ethical criteria of the “all-affected principle” and the effective criteria of “de facto governance”. In this way, it responds to the four procedural dimensions of anticipation, inclusion, reflection and responsiveness of the RRI framework. It also provides a starting point on how four of the multiple agendas and key research topics can be specified in the ETHNA System, namely: research integrity, the gender perspective, open access and public engagement.

The ETHNA System offers ethics governance structures based on a system of flexible blocks that can be adapted to the needs and particular features of each organisation and their available resources. The ETHNA System allows organisations to build their own ethics governance structure for knowledge-generation and innovation processes, and make progress by continuously improving them over time.

As has already been indicated, one of the aspects to continue working on within this sustained improvement model is to address other issues with this same system, such as environmental sustainability or social justice in R&I, among other agendas or issues shown to be demands or requirements of society. In short, where research and innovation should be open to continue addressing these and other issues, together with society. In our view, the ETHNA System allows for this continuous openness to the values and social and ethical expectations of its stakeholders through its ethics governance system.

References

Horn, L.: Promoting responsible research conduct: a south african perspective. J. Acad. Ethics 15(1), 59–72 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9272-8

Hoecht, A.: Whose ethics, whose accountability? a debate about university research ethics committees. Ethics Educ. 6(3), 253–266 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2011.632719

Moan, M.H., Ursin, L., de Grandis, G.: Institutional governance of responsible research and innovation. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, 13875. Springer, Cham (2023)

Cortina, A., García Marzá, D., Conill, J. (eds.): Ashgate, Aldershot (2008)

Habermas, J.: Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics. Polity Press, Boston (1993)

Häberlein, L., Hövel, P.: Importance and necessity of stakeholder engagement. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, 13875. Springer, Cham (2023)

Hajdinjak, M.: Implementing RRI in a non-governmental research institute. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, 13875. Springer, Cham (2023)

Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Ferrada, F., Oliveira, A.I.: Implementing RRI in a research and innovation ecosystem. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, 13875. Springer, Cham (2023)

Bernal-Sánchez, L., Feenstra, R.A.: Developing RRI and research ethics at university. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, LNCS, 13875. Springer, Cham (2023)

Landeweerd, L., Townend, D., Mesman, J., Van Hoyweghen, I.: Reflections on different governance styles in regulating science: a contribution to ‘responsible research and innovation.’ Life Sci., Soc. Policy 11(1), 1–22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40504-015-0026-y

Stilgoe, J., Owen, R., Macnaghten, P.: Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 42(9), 1.568–1.580 (2013) https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2011.632719

Stilgoe, J., Owen,R., Macnaghten, P., Stilgoe, J., Macnaghten P., Gorman M., et al.: Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 42(9), 1,568–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

Jonas, H.: The Imperative of Responsibility. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1984)

Von Schomberg, R.: A vision of responsible research and innovation. In: Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M. (eds): Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, pp. 51–74. John Wiley & Sons Inc., Chichester, West Sussex (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118551424.ch3

Owen, R., von Schomberg, R., Macnaghten, P.: An unfinished journey? reflections on a decade of responsible research and innovation. J Responsible Innov. 8(2), 217–233 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.1948789

Von Schomberg, R., González-Esteban, E., Sanahuja-Sanahuja, R.: Ethical challenges and limits of RRI for improving the governance of research and innovation processes. Recer Rev Pensam i Anàlisi. 27(2), 1–6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.6035/recerca.6750

Owen, R., Pansera, M.: Responsible innovation and responsible research and innovation. In: Simon D., Kuhlmann S., Stamm J., Canzler W. (eds): Handbook on Science and Public Policy, pp. 26–48. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA (2019), https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715946.00010

Owen, R., Stilgoe, J., Macnaghten, P., Gorman, M., Fisher, E., Guston, D. A framework for responsible innovation. In: Owen R., Bessant J., Heintz M., (eds.): Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 27–50 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118551424.ch2

Rip, A.: The past and future of RRI. Life Sci. Soc. Policy 10(1), 1–15 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40504-014-0017-4

Stahl, B.C., Eden, G., Jirotka, M., Coeckelbergh, M.: From computer ethics to responsible research and innovation in ICT. The transition of reference discourses informing ethics-related research in information systems. Inf. Manag. 51, 810–818 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.01.001

Beck, U., Ritter, M.: Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage Publications, London (1992)

González-Esteban, E.: Ética y gobernanza: un cosmopolitismo para el siglo XXI. Granada, Comares (2013)

Irwin A. The Politics of Talk: Coming to Terms with the “New” Scientific Governance. 36, Social Studies of Science, pp. 299–320 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312706053350

Schuijff, M., Dijkstra, A.M.: Practices of responsible research and innovation: a review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26(2), 533–574 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00167-3

Godecharle, S., Nemery, B., Dierickx, K.: Heterogeneity in european research integrity guidance: relying on values or norms. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 9(3), 79–90 (2014)

González-Esteban, E.: ¿Qué tipo de reflexividad se necesita para fomentar la anticipación en la RRI? una visión ético-crítica. In: Rodriguez Zabaleta, H., Ureña López, S., Eizagirre Eizagirre, A., Imaz Alias, O. (eds.) Anticipación e innovación responsable: la construcción de futuros alternativos para la ciencia y la tecnología, pp. 229–249. Minerva Ediciones, Barcelona (2019)

Habermas, J., The Idea of the University: Learning Processes. New Ger Crit. 1987; (41, Special Issue on the Critiques of the Enlightenment), pp. 3–22

García-Marzá, D.: From ethical codes to ethical auditing: an ethical infrastructure for social responsibility communication. El Prof la Inf. 26(2), 268–276 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.mar.13

García-Marzá, D., Fernández Beltrán, F., Sanahuja, R.: Ética y Comunicación en la gestión de la investigación e innovación responsable (RRI). El papel de las unidades de cultura científica y de la innovación (UCC+I). Castellón de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I (2017). https://doi.org/10.6035/Humanitats.2017.52

Flipse, S.M., van der Sanden, M.C.A., Osseweijer, P.: The why and how of enabling the integration of social and ethical aspects in research and development. Sci. Eng. Ethics 19(3), 703–725 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-012-9423-2

Özdemir, V.: Towards an ethics-of-ethics for responsible innovation. In: von Schomberg R., Hankins J., (eds): International Handbook on Responsible Innovation: A Global Resource. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 70–82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784718862.00011

European Commission. Responsible Research and Innovation. Europe’s ability to respond to societal challenges, p. 4 (2014). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2be36f74-b490-409e-bb60-12fd438100fe

Guston, D.H.: Understanding “anticipatory governance.” Soc Stud Sci. 44(2), 218–242 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312713508669

Guston, D.H., Sarewitz, D.: Real-time technology assessment. Technol Soc. 24(1–2), 93–109 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-791X(01)00047-1

Eizagirre, A.: Investigación e innovación responsables: retos teóricos y políticos. Sociol Probl e Práticas. 2017(83), 99–116 (2016). https://journals.openedition.org/spp/2713?lang=pt

Braun, R., Griessler, E.: More democratic research and innovation. J. Sci. Commun. 17(3), 1–7 (2018). https://jcom.sissa.it/article/pubid/JCOM_1703_2018_C04/

Burget, M., Bardone, E., Pedaste, M.: Definitions and conceptual dimensions of responsible research and innovation: a literature review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 23(1), 1–19 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9782-1

Forsberg, E.-M., Shelley-Egan, C., Ladikas, M., Owen, R.: Implementing responsible research and innovation in research funding and research conducting organisations—what have we learned so far? In: Governance and Sustainability of Responsible Research and Innovation Processes. SRIG, pp. 3–11. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73105-6_1

van Hove, L., Wickson, F.: Responsible research is not good science: divergences inhibiting the enactment of RRI in nanosafety. NanoEthics 11(3), 213–228 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-017-0306-5

Owen, R., Macnaghten, P., Stilgoe, J.: Responsible research and innovation: from science in society to science for society, with society. Sci. Public Policy 39(6), 751–760 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs093

Von Schomberg, R.: Towards Responsible Research and Innovation and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg (2011). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/60153e8a-0fe9-4911-a7f4-1b530967ef10

Von Schomberg, R.: Prospects for technology assessment in a framework of responsible research and innovation. In: Dusseldorp M., Beecroft R., editors. Technikfolgen abschätzen lehren: Bildungspotenziale transdisziplinärer Methode. Springer, Wiesbaden, pp. 39–61 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93468-6_2

García-Marzá, D., Fernández Beltrán, F., Sanahuja, R., Andrés, A.: El diálogo entre ciencia y sociedad en España. Experiencias y propuestas para avanzar hacia la investigación y la innovación responsables desde la comunicación. Castellón de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I (2017). https://doi.org/10.6035/FCT.16.11124.2018

Stilgoe, J., Lock, S.J., Wilsdon, J.: Why should we promote public engagement with science? Public Underst Sci. 23(1), 4–15 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662513518154

Von Schomberg, R.: From the ethics of technology towards an ethics of knowledge policy & knowledge assessment. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg (2007). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/aa44eb61-5be2-43d6-b528-07688fb5bd5a

Honneth, A.: The Critique of Power: Reflective Stages in a Critical Social Theory. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (1991)

Gianni, R.: Choosing freedom: ethical governance for responsible research and innovation. In: von Schomberg, R., Hankins, J., (eds): International Handbook on Responsible Innovation: A Global Resource. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 49–69 (2019). https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784718862.00010

Wynne, B.: Public uptake of science: a case for institutional reflexivity. Public Underst Sci. 2, 321–337 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/2/4/003

Taebi, B., Correljé, A., Cuppen, E., Dignum, M., Pesch, U.: Responsible innovation as an endorsement of public values: the need for interdisciplinary research. J. Responsible Innov. 1(1), 118–124 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2014.882072

ETHNA System Project. https://ethnasystem.eu/about-ethna/the-project/

González-Esteban, E., et al.: The ETHNA system – a guide to the ethical governance of RRI in innovation and research in research performing organisations and research funding organisations. Deliverable 4.2 Draft concept of the ETHNA System. ETHNA Project [872360] Horizon (2020). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6532789

European Science Foundation, ALLEA – All European Academies. The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, pp. 1–20 (2011). https://allea.org/code-of-conduct/

Habermas, J.: The Theory of Communicative Action, vol. 2. Beacon Press, Boston (1987)

Stahl, B.C.: Morality, ethics, and reflection: a categorization of normative is research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 13(8), 636–656 (2012). https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00304

Rehg, W.: Discourse ethics for computer ethics: a heuristic for engaged dialogical reflection. Ethics Inf. Technol. 17(1), 27–39 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-014-9359-0

Sorensen, E.: The metagovernance of public innovation in governance networks. In: Paper presented at the Policy and Politics Conference in Bristol (2014)

Sorensen, E., Torfing, J.: Making governance networks effective and democratic through metagovernance. Public administration. Public Adm. 87(2), 234–58 (2009). https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/sps/migrated/documents/sorensonthemetagovernanceofpublicinnovation.pdf

Kooiman, J.: Social-political governance: overview, reflections and design. Public Management and international journal of research and theory. Public Manag Int. J. Res. Theory. 1(1), 67–92 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037800000005

Hovdal Moan, M., Ursin, L., González-Esteban, E., Sanahuja Sanahuja, R, Feenstra, R., Calvo, P., et al.: ETHNA system: literature review and state of the art description. Mapping examples of good governance of research and innovation (R&I) related to responsible research and innovation (RRI), in Higher Education, Funding and Research Organisations (HEFRCs) (2022). https://ethnasystem.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ETHNA_Report_state-of-the-art.pdf

Szüdi, G., Lampert, D., Hajdinjak, M., Asenova, D., Alves, E., Bidstru, M.V.: Evaluation of RRI institutionalisation endeavours: specificities, drivers, barriers and good practices based on a multi-stakeholder consultation and living lab experiences. In: Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice, Springer, Cham (2023)

Adobor, H.: Corporate ethics officers. In: Poff, D.C., Michalos, A.C., (eds): Encyclopedia of Business and Professional Ethics. Springer Nature, Switzerland (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23514-1_66-1

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the European Project “Ethics Governance System for RRI in Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres” [872360], funded by the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

González-Esteban, E. (2023). The ETHNA System and Support Tools. In: González-Esteban, E., Feenstra, R.A., Camarinha-Matos, L.M. (eds) Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13875. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33177-0_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33177-0_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33176-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33177-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)