Abstract

The study examines whether information security behaviour (ISB) in an organisation providing critical infrastructure improved after systematic efforts to improve information security culture (ISC) through the implementation of an information security management system (ISMS). The data are based on quantitative surveys before (N = 323) and after (N = 446) efforts to improve ISC in the organisation. Qualitative interviews were also conducted before (N = 22) and after (N = 12). The study finds that the organisation has managed to improve its ISC through systematic efforts over a two-year period (2014–2016), and that this also has led to improvements in ISB among the personnel in the organisation. Multivariate regression analyses indicate that ISC is the most important variable influencing ISB, while ISMS measures is the most important variables influencing ISC. Thus, our results indicate that it is important to work with ISMS and ISC to increase IS in our increasingly digitalised society, especially in organisations providing critical infrastructure.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

10.1 Introduction

10.1.1 Background

One of the key aspects of increased digitalisation of society’s functions, especially those related to critical infrastructure, is that it introduces new vulnerabilities, indicating the need for new types of protection. An important insight in this respect is the critical importance of human and cultural factors for the security level of critical infrastructure. According to Lim et al. [1], security is becoming more challenging in today’s business because people are both a cause of information security (IS) incidents as well as a key part of the protection from them. In this context, physical and technological measures provide an insufficient strategy for protection. Several studies indicate the critical importance of information security behaviour (ISB) for IS in organisations, suggesting that these behaviours often reflect more general patterns of information security culture (ISC) in the organisations [1–3].

We define ISBs as behaviours that are relevant to IS. IS is often defined as protection against breaches of confidentiality, integrity and accessibility. This applies to information that is oral, written or electronic. Confidentiality refers to ensuring that only those who are authorised to access information, accesses it. Integrity refers to protecting the accuracy and entirety of information and processing methods. Accessibility refers to ensuring that authorised users have access to the information and associated equipment when necessary. We define ISC as shared and information security relevant ways of thinking or acting that are (re)created through the joint negotiation of people in social settings.

According to Chen et al. [2], previous studies have paid little attention to the important influence of ISC on ISB. Additionally, Chen et al. [2] state that there is little research on the relationship between comprehensive efforts to manage IS and ISC. We may also refer to such efforts as an information security management system (ISMS), which defines policies and procedures to ensure, manage, control and continuously improve IS in an organisation. One of the most prevalent ISMS is the ISO 27001 standard, which involves systematic efforts to ensure confidentiality, integrity and accessibility.

10.1.2 Aims

In this chapter, we address the research gap identified by Chen et al. [2] by studying whether the implementation of an ISO 27001 compliant ISMS (and additional measures) has led to changes in ISC and subsequently IS in an organisation providing critical infrastructure.

The aims of the study are to:

-

(1)

describe the organisation’s efforts to improve ISC through the implementation of an ISMS;

-

(2)

compare ISC in the organisation before (2014) and after (2016) the efforts to improve ISC, and examine factors influencing ISC in the organisation;

-

(3)

compare ISB in the organisation before (2014) and after (2016) efforts to improve organisational ISC, and examine factors influencing ISB in the organisation.

We compare implementation and effect in the six departments of the organisation.

10.1.3 Previous Research

10.1.3.1 Information Security Management System

An ISMS consists of formal routines and measures that enable the organisation to work systematically to avoid breaches of confidentiality, integrity and accessibility, by establishing formal safety policies and goals, establishing important roles and responsibilities, conducting risk analyses systematically gathering information on incidents and dangers, developing countermeasures, monitoring the effects of these and adjusting measures if necessary (cf. Mitsch et al. [4]).

Other key elements in an ISMS are role descriptions with responsibilities, reporting systems, risk assessments, security training, security procedures, etc. The security policy states security goals and how these are to be achieved via ISMS. The procedures for achieving the goals are documented, along with who is responsible for doing what.

Although the implementation of an ISMS, e.g., ISO 27001, is often cited as an important way of establishing an ISC, there seems to be few studies which have actually examined this relationship (cf. [2]). The relationship between management systems and culture is, however, well established in the research on safety culture [5].

10.1.3.2 Information Security Culture

While an ISMS refers to the formal aspects of IS management (“how things should be done”), as it is described in procedures, manuals, etc., the informal aspects of IS management generally refer to ISC (“how things are actually done”) [6]. ISC is often studied using various concepts and models of organisational culture [1]. Although Ruighaver et al. [7] note that the organisational security culture concept has gained recognition, they also underline the lack of consensus on definitions and concepts (cf. [8]). Additionally, they assert that in spite of a large amount of research on organisational security and how it should be improved, this research only focuses on certain aspects of security, and not how these aspects can be analysed as part of a larger organisational culture [7]. Based on this understanding, they choose to draw on organisational culture research in their analysis of ISC. This approach is similar to that applied by scholars studying organisational safety culture, who analyse safety culture as a focused and safety-relevant aspect of the larger organisational culture (e.g., [6]). Based on this, we may also analyse ISC as “security-relevant” aspects of the larger organisational culture, defined and conceptualised using models of organisational culture. When studied qualitatively, ISC refers to common frames of reference that form the basis for interpretations of actions, hazards and our own identity, and which motivate and legitimise behaviour that affects IS (cf. [6, 9]). Such common frames of reference arise through interaction in groups. When studied quantitatively, ISC is measured as the way IS is valued in the organisation by managers and employees and their perceptions of the ISMS, or “the way things actually are done” when it comes to IS.

10.1.3.3 Information Security Behaviour

Lim et al. [1] cite several studies indicating that IS problems in organisations have been linked to employee behaviour. These behaviours are typically different types of violations and non-compliance with IS procedures, indicating that it is not sufficient to have a formal system in place, if it is not supported by the ISC [1]. This indicates the importance of viewing IS behaviours as part of a larger ISC context.

10.1.3.4 Theoretical Model and Hypotheses

Based on previous research, we have developed the following theoretical model and hypotheses:

-

(1)

Hypothesis 1: implementation of ISMS measures will lead to improvements in ISC;

-

(2)

Hypothesis 2: the departments with the best ISMS implementation will have the best ISC improvements;

-

(3)

Hypothesis 3: improvement in ISC has led to improvement in ISB.

10.2 Methods

10.2.1 Qualitative Interviews

We used a semistructured and relatively open interview guide, focusing on security work in the organisation since 2014. The interviews were built up around the following main topics: (a) IS measures since 2014 and ISMS implementation, (b) follow-up of the 2014 ISC survey and (c) managers and employees’ perceptions of IS rules and measures.

10.2.2 Quantitative Survey

10.2.2.1 Survey Items

The survey contains a set of background questions (e.g., gender, age, experience, education). The survey also includes questions measuring ISMS measures and implementation, e.g., questions about each department's follow-up of the survey results in 2014 and information about specific IS issues over the past two years (e.g., passwords, security policy for mobile units, policies for strangers in the premises) (cf. Sect. 3.1.2).

In this study, we choose to reformulate one of the few existing universal organisational safety culture scales, the GAIN scale [10] for safety culture, into an organisational security culture scale. The questionnaire contains 24 questions concerning, e.g., respondents’ perceptions of management’s and employees’ focus on information security, reporting of information security issues. Respondents can rate the questions from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). Thus, a security culture index with a minimum value of 24 (1 × 24) and a maximum value of 120 (5 × 24) can be compared across companies and sectors.

We have one question measuring ISB: “When I am asked for information, I always think carefully about whether the information can be used for purposes other than its intended purpose”.

10.2.3 Samples

We compare the results of two surveys done over a period of just over two years; the first in the spring of 2014 and the second in the autumn of 2016. Response rates are provided in Table 10.1.

10.3 Results

10.3.1 IS Management System Implementation

10.3.1.1 Qualitative Results

The study organisation is a provider of critical infrastructure in Norway. As a provider of critical infrastructure, it is obliged to follow the requirements of the Safety Act (“Sikkerhetsloven”) when it comes to preventive safety work, which includes safety analyses, securing objects, IS and safety drill.

The study organisation decided to map and analyse its ISC in 2014, due to its legal obligations, work activities and engagement. The organisation used the measurement of ISC in 2014 as an indicator of the IS level in the organisation and as a basis for identification of critical areas (related to attitudes, knowledge, practices) in need of improvement. Based on this, future goals for improvement were established, both at a general level and at a more specific level. A score of 87 or higher on the ISC index was established as a general goal for all departments. The 2014 survey identified needs when it comes to, e.g., increasing IS knowledge, attitudes and engagement among the personnel.

Several measures were taken to improve IS. Department managers were given the task of presenting the results from the 2014 ISC survey to their employees, discuss the results and measures that could be implemented to improve the status on the specific challenges discussed. A number of actions were taken: digital and on-site intrusion test, strengthened physical access control in the facilities, access card pin codes, new password policy, VPN dashboard and stronger fire wall policy (including strengthened fire wall and two-factor authentication), new routines for use of access card and visitor registration, internal training on password handling, handling of physical documents in field operations, photography and social media, office and document access in-house and information on possible consequences of negligent information leaks relating to security critical objects.

Second, the organisation started to establish a basic safety organisation in 2014, describing roles and responsibilities, as well as principles and guidelines related to IS. This was developed in accordance with the ISO 27001 principles. The implemented ISMS is particularly linked to the administrative department’s responsibilities, the role of security coordinators and systematic risk analyses on all processes and goals relating to IS. A security coordinator was appointed, with a special responsibility to provide systematic training of the personnel in IS issues, to coordinate and train security coordinators in each department and to further develop IS protocols and instructions. The organisation reviewed all information related to security critical objects, crisis plans, security certifications and critical ICT systems, defining information into three categories: (a) open, (b) internal, (c) sensitive and graded. Additionally, new policies were developed for personal information, graded information, acceptable use of information and security policy for mobile units. The organisation developed a security declaration for employees to sign, documenting that they had received all the required training and information. A new system for recording and dealing with non-conformities was developed. The organisation also started to arrange an annual security month, and information security became a mandatory theme in each manager meeting. In spite of all these measures, interviewees agreed that challenges remained and that there were needs for improvement and maturing of the ISMS.

10.3.1.2 Quantitative Results

We asked the respondents three questions about the follow-up of the ISC measurement in 2014. We introduced the questions with the text: “We want to know a little about what actions your immediate supervisor has taken in your department/section after the evaluation of the ISC in 2014”.

The head of my department/section has gone through the results of the evaluation with us

My department/section has taken steps to improve the ISC (e.g., focus on passwords and security-critical information) based on the results of the evaluation

I am satisfied with how my department/section has worked on IS over the past two years

We also asked the respondents three questions related to whether they have received useful information over the past two years that has increased their knowledge and awareness of IS. These questions measure training in IS:

During the past two years I have received useful information (e.g., from security coordinator, manager, intranet) about what a secure password is

During the past two years, I have received information (e.g., from security coordinator, manager, intranet) that made me more aware of strangers in our premises

During the past two years, I have received information (e.g., from the security coordinator, manager, intranet) that has given me more insight into what security-critical information is

We made two indexes based on these six questions (cf. Table 10.2). The first on follow-up, the second on training. All the questions include six response options: 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree and 6 = have no knowledge about this. When we created the indexes, we removed the sixth response option.

Table 10.2 indicates the highest levels of follow-up in department 6, 1 and 5, and the highest levels of training in department 6, 5 and 1.

10.3.2 Improvements in ISC

We have combined the 24 statements with five response options on the five different aspects of IS in an ISC index. The indexes for the departments correspond to the average scores for the respondents. The minimum score is 24 (24 × 1), and the maximum score is 120 (24 × 5) (Table 10.3). Cronbach’s Alpha for the 24 questions in the index was 0.913 in 2014, which means very good agreement between the questions and that the index is very good.

We see that the Department 6 (again) had the highest score in 2016 and 2014, followed by Department 2 and Department 1. All the departments saw an improvement on the ISC index in 2016, especially Department 1, which increased by 12 points on the index. The average improvement for all the departments from 2014 to 2016 was 9 points. This change is statistically significant at the 1% level. The differences between the departments are significant at the 1% level, both in 2014 and 2016.

GAIN [10] defines different types of culture, based on the scores of the index. The limits for “positive culture” range from 88 to 120 points on the GAIN index. The moderate culture scale goes from 47 points to a maximum of 87 points, and scores below 46 points correspond to a poor culture. If we are to transfer the GAIN scale values from safety culture to ISC, we see that none of the departments had a positive ISC in 2014. However, in 2016 we find that Department 6, Department 2 and Department 1 were within the part of the scale that we refer to as a positive culture.

10.3.2.1 Which Factors Influence ISC?

In Table 10.4, we examine the variables influencing respondents’ ISC. We include variables measuring ISMS implementation and background variables.

Table 10.4 indicates two main results. The first is that the follow-up index is the strongest predictor of respondents’ ISC. We see that the department variable ceases to contribute significantly from Model 4 to Model 5, when the follow up variable is included. This indicates that this variable is related to follow-up, i.e., that this department has a higher score on the ISC index, due to the follow-up of the 2014 survey of ISC. The second main result is that the training index also contributes significantly and positively, indicating that IS training is related to a higher score on the ISC index. The Adjusted R2 value in Model 6 is 0.641, indicating that the model explains 64% of the variation in the dependent variable.

10.3.3 Improvements in Information Security Behaviour

Table 10.5 shows results on the question: “When I am asked for information, I always think carefully about whether the information can be used for purposes other than its intended purpose”, in 2014 and 2016.

Table 10.4 indicates the highest level of improvement in Departments 6 and 5, followed by Departments 4 and 1.

10.3.3.1 Which Factors Influence Information Security Behaviours?

In Table 10.6, we examine the variables influencing respondents’ ISB. We include variables measuring ISC, IS knowledge and background variables.

Table 10.6 indicates two main results. The first is that the ISC index is a strong and significant predictor of the ISB of the respondents. We see that the department variable ceases to contribute significantly from Model 4 to Model 5, when the ISC index is included. This indicates that this variable is related to ISC (i.e., that the ISC score is higher in this department). The second main result is that respondents’ IS knowledge also is a strong and significant predictor of their ISB. Knowledge is measured as the degree of agreement with the statement: “I am well aware of which kind of information that is sensitive and security graded”. The Adjusted R2 value in Model 6 is 0.207, indicating that the model explains 21% of the variation in the dependent variable.

10.4 Discussion

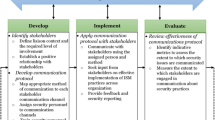

10.4.1 The Implementation of ISMS

The first aim of the study was to describe the efforts to improve information security culture through the implementation of an ISMS. The study organisation has implemented several efforts to manage IS following the first measurement of ISC in 2014. In accordance with the continuous improvement approach inherent in ISMS, the organisation used the 2014 measurement as a baseline for future improvement, treating ISC as a broad indicator of IS in the organisation. Improvement goals were agreed upon, which were going to be followed up in a new measurement. In the meantime, several organisational measures were implemented and/or improved, e.g., related to the security coordinator, training, risk analyses and procedures. These were developed in accordance with ISO 27001 principles. As a consequence, interviewees in 2016 agreed that they had established a basic “security organisation” through the implemented measures.

10.4.2 How Can We Explain the Improvements in Information Security Culture?

The second aim of the study was to compare information security culture in the organisation before (2014) and after (2016) efforts to improve organisational information security culture, and examine factors influencing ISC. Our analyses indicate a 12% increase in the score for ISC in the organisation, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. Multivariate analyses indicate that variables measuring ISMS implementation were the most important predictors of ISC. This is in accordance with Hypothesis 1, stating that implementation of ISMS measures will lead to improvements in ISC. The follow-up index, measuring the follow-up of the 2014 measurement of ISC in each department was the strongest predictor of the respondents’ ISC. This indicates the importance of such group-wise processes of continuous improvement, when it comes to developing ISC. The rates of improvement in ISC also varied between the different departments; ranging from 2.5% to 15% improvement. In line with Hypothesis 2, results indicate that the departments with the best implementation had the best improvements in ISC. This especially applies to department 6. According to Chen et al. [2], there is little research on the relationship between comprehensive IS programs and ISC. In this study, we contribute to this knowledge gap by studying how the ISMS measures of the study organisation have contributed to improvements in ISC and subsequently ISB.

10.4.3 How Can We Explain the Improvements in Information Security Behaviours?

The third aim of the study was to compare information security behaviour in the organisation before (2014) and after (2016) efforts to improve organisational information security culture, and examine factors influencing ISB. Our analyses indicate an 8% increase in the average score in the examined ISB from 2014 to 2016, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. These changes were also significant when controlled for factors like the age and education of the respondents. Multivariate analyses indicate that the ISC index and IS knowledge were the most important predictors of ISB. This result is in line with Hypothesis 3, stating that improvements in ISC will lead to improvement in ISB. This is in accordance with previous research indicating a relationship between ISC and ISB [1–3]. The rates of improvements in behaviour varied among the different departments in the organisation, ranging from 3% improvement in Department 3 to 16% in Department 6, again indicating the importance of effective ISMS implementation for ISC and ISB results. The ISC index measures questions related to management and employee focus on IS, IS training, etc. Our results indicate that this is positively related to our measure of ISB, which is related to confidentiality: “always thinking carefully about whether requested information can be used for purposes other than its intended purpose”.

10.4.4 Safety Culture Versus Security Culture

We used a modified organisational safety culture scale [10] to measure ISB. The scale was chosen as the research on organisational safety culture seems to have been through many of the challenges that the organisational security culture research now is facing (cf. Ruighaver et al. [7]). At the same time, the research on organisational safety culture seems to have matured a bit more conceptually and methodologically, as it has employed the culture perspective for a few more years than the field of security research. We therefore draw on the experiences of the safety culture literature.

There are however several important differences between safety culture and security culture and the applications of the concepts. First, the difference between sharp end and blunt end is harder to see in the field of security. All members of the organisation are in one sense in the security sharp end, as they are users of information, equipment and facilities. Additionally, the results of serious security incidents and non-conformities may remain unseen and unnoticed for a long time. The same applies to latent system failures, which may be exploited undetected for long periods by third parties. Security incidents are generally not physical accidents with immediate damages or injuries. A consequence of this is that it may be even more difficult to define a state of “security” (e.g., as the absence of serious security incidents) than it is to define a state of “safety” (e.g., as the absence of physical accidents).Footnote 1 Thus, security is a more abstract state than safety, making security assessments and preventive efforts more challenging.

It could also be mentioned that in the field of security, the distinction between the private domain and work domain is blurred, as employees use digital workplace equipment (e.g., phones, tablets, computers) in their leisure time. Thus, they must also act according to their ISMS and ISC after working hours and in their private spheres. Thus, in contrast to the field of safety, the field of security requires employees to be always “at work”. This has interesting implications for ISC management: it stretches into both the professional and the private sphere.

Another difference is related to intent: safety culture mainly concerns prevention of incidents related to combinations of technological, (unintentional) human and organisational risk factors, while security culture concerns prevention of incidents related to combinations of technological, (intentional) human and organisational risk factors. As the human component in the security field often deals with intentional actors with hostile intentions, the possibilities for failure (security breaches) are greater. In the case of safety, human risk factors are typically related to unintended errors, mistakes and violations, combined with technological and organisational weaknesses. In the case of security, these risk factors at the “victim end” are combined with the creativity, expertise and imagination of intentional human actors at the “offender end”. An implication of this is that security management also is related to crime prevention.

Finally, the most important similarity between safety and security management is that physical and organisational measures are important for increasing both safety and security, but as long as human actors use these systems and relate to the physical measures, the state of safety and security is contingent on the behaviours and subsequently the culture of these actors. This indicates the crucial importance of ISC for IS and the importance of organisational safety culture for safety.

10.5 Conclusion

The study finds that the organisation providing critical infrastructure has managed to improve its ISC through systematic ISMS efforts over a two-year period (2014–2016), and that this also has led to improvements in ISB among the personnel. Multivariate analyses indicate that ISC is the most important variable influencing ISB. Respondents’ knowledge about IS was also an important variable in the analyses. Thus, our results indicate that it is important to work with organisational ISC and knowledge to increase IS in our increasingly digitalised society, especially in organisations providing critical infrastructure.

Notes

- 1.

This may also be the case with latent organisational or technological safety failures, which may exist undetected until they interact with active failures in ways that lead to accidents. Given the abstract character of security, preventing unwanted security incidents may have more to learn from research on safety culture in complex technological systems, where technological failures may act in unseen, unanticipated and incomprehensible manners due to “interactive complexity” (cf. Perrow [15]). Previous research indicates that cultural management is particularly important in these settings (cf. Weick et al. [16]).

References

J.S. Lim, S. Chang, S. Maynard, A. Ahmad, Exploring the relationship between organizational culture and information security culture, in Proceedings of the 7th Australian Information Security Management Conference, 1–3 December 2017 (Perth, Western Australia, 2017)

Y.K. Chen, K. Ramamurthy, K.-W. Wen, Impacts of comprehensive information security programs on information security culture. J. Comp. Inform. Syst. 55(3), 11–19 (2015)

A.R. Nasir, A. Arshah, M.R.A. Hamid, S. Fahmy, An analysis on the dimensions of information security culture concept: a review. J. Inform. Secur. Appl. 44(2019), 12–22 (2019)

M. Mirtsch, J. Pohlisch, K. Blind, International Diffusion of the Information Security Management System Standard ISO/IEC 27001: Exploring the Role of Culture. Research Papers, p. 88 (2020)

T.-O.I.S. Nævestad, K. Hesjevoll, S.A. Ranestad, Strategies regulatory authorities can use to influence safety culture in organizations: Lessons based on experiences from three sectors. Saf. Sci. 118(2019), 409–423 (2019)

S. Antonsen, The relationship between culture and safety on offshore supply vessels. Saf. Sci. 47(8), 1118–1128 (2009)

A.B. Ruighaver, S.B. Maynard, S. Chang, Organisational security culture: Extending the end-user perspective. Comp Secur. 26, 56–62 (2007)

P. Chia, S. Maynard, A.B. Ruighaver, in Understanding organizational security culture, in Sixth Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, 2–3 September 2002 (Tokyo, Japan, 2002)

T.-O. Nævestad, Cultures, crises and campaigns: Examining the role of safety culture in the management of hazards in a high risk industry. Ph.D. dissertation, Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo (2010)

GAIN (Global Aviation Network), in Operator’s Flight Safety Handbook (2001). http://flightsafety.org/files/OFSH_english.pdf

T.O. Nævestad, J. Hovland Honerud, S. Frislid Meyer, Organizational information security culture in critical infrastructure: developing and testing a scale and its relationships to other measures of information security, in Safety and Reliability—Safe Societies in a Changing World, Proceedings of ESREL 2018, June 17–21, 2018, Trondheim, Norway, ed. by S. Haugen, A. Barros, C. van Gulijk, T. Kongsvik, J.E. Vinnem (CRC Press, London, 2018a)

T.-O. Nævestad, J. Hovland Honerud, S. Frislid Meyer, How can we explain improvements in organizational information security culture in an organization providing critical infrastructure?, in Safety and Reliability—Safe Societies in a Changing World, Proceedings of ESREL 2018, June 17–21, 2018, Trondheim, Norway, ed. by S. Haugen, A. Barros, C. van Gulijk, T. Kongsvik, J.E. Vinnem (CRC Press, London, 2018b)

K.J. Knapp, T.E. Marshall, R.K. Rainer, F.N. Ford, Information security management’s effect on culture and policy. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 14(1), 24–36 (2006)

E.H. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd edn. (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2004)

C. Perrow, Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies (Basic Books, New York, 1984)

K.E. Weick, Organizational culture as a source of high reliability. Calif. Manage. Rev. 24(2), 112–127 (1987)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

The methods for data collection in the present project are in accordance with the ethics policies and requirements of the Institute of Transport Economics and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). NSD assists researchers with research ethics of data gathering, data analysis and issues of methodology. The study was reported to NSD. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Oral informed consent was obtained from participants, and all data have been anonymised.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nævestad, TO., Honerud, J.H., Meyer, S.F. (2023). Information Security Behaviour in an Organisation Providing Critical Infrastructure: A Pre-post Study of Efforts to Improve Information Security Culture. In: Le Coze, JC., Antonsen, S. (eds) Safety in the Digital Age. SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32633-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32633-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-32632-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-32633-2

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)