Abstract

Peer feedback has proven to be very beneficial for student learning; however, by its social nature, peer feedback raises concerns for many students. To diminish these, and maximize the benefits of a peer feedback activity, we created an online training targeting psychological safety and trust. The objective of this chapter is to describe the design process and to detail the composition of the training. The training was delivered to higher education students and included five stages: discovery of students’ representation, lecture on how to provide effective feedback, peer feedback practice, role-play and discussion in small groups and summary of key learning points. A questionnaire one month after the training and interviews with five students revealed that students’ engagement in and perceptions of the training were highly variable. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Peer Feedback and Its Social Nature

1.1 The Benefits of Peer Feedback

How to foster student learning is a crucial question in educational research. Feedback—defined as “a process through which learners make sense of information from various sources and use it to enhance their work or learning strategies” (Carless & Boud, 2018, p. 1)—has been proposed as an important tool for student learning and numerous studies have confirmed this (e.g. Black & Wiliam, 1998; Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Indeed, in a recent meta-analysis of 435 studies, Wisniewski and his colleagues (2020) found that feedback has a moderate size effect (d = 0.48) on students’ learning.

A particularly effective kind of feedback is feedback from peers. Indeed, empirical evidence supports the value of peer feedback and suggests it can even be a more useful tool for learning than teacher feedback. Wisniewski et al. (2020) found student-to-student feedback to be more efficient than teacher-to-student feedback. In another recent meta-analysis, Double and his colleagues (2020) addressed the effect of peer assessment (which sometimes, but not always include peer feedback). Based on 54 (quasi-) experimental studies, this meta-analysis concludes that peer assessment impacts student learning more positively than teacher assessment.

The value of peer feedback does not only lies in the fact it helps students to developed specific subject-related learning, it also pushes them to develop more general feedback skills (Carless et al., 2011). By giving opportunities for students to practice making judgements, peer feedback contributes, for example, to the development of evaluative judgment, which is defined as “the capacity to make decisions about the quality of work of self and others (Tai et al., 2018, p. 471)”. Evaluative judgement is a necessary skill for students to become independent lifelong learners, which should be a goal of higher education (Tai et al., 2018).

1.2 Students’ Concerns and How to Take Them into Account

Given that peer feedback can be a very beneficial activity for students’ learning, we could expect students to be eager to participate in peer assessment activities. However, this is only partly the case. Indeed, the majority of students report to like peer assessment and to find it useful (Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Mulder et al., 2014). However, they also express a series of concerns. These concerns are various but have a common element: they emerge from the fact that peer assessment is a social experience (e.g. Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Mulder et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2015). Some students fear, for example, that their peers will be biased or will not put enough effort into their assessment, feel they lack the skills to evaluate their peers, find it difficult to be objective and feel uncomfortable evaluating their peers and being evaluated by them (Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Mulder et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2015). These concerns are not anecdotic: in Stanier (1997)’s study, 40% of the students found peer assessment to be an uncomfortable experience and in Mostert and Snowball (2013)’s study, 29% felt that their peers did not engage enough in the activity and 19% did not trust their peers as assessors.

The main suggestion in literature to overcome students’ concerns linked to the social nature of peer feedback is anonymity. In Yu and Liu (2009)’s study, for example, students preferred using a surname rather than their real name in a peer assessment activity and, in Vanderhoven et al. (2015)’s study, students experienced less peer pressure and fear of disapproval in an anonymous peer assessment activity compared to a non-anonymous one. Rotsaert et al. (2018) have found that, when peer feedback is used multiple times in a course, fading anonymity can be used as an instructional scaffold. When students first had the opportunity to experience peer feedback anonymously, they continue to provide feedback of the same quality and to feel safe when anonymity is removed and the importance they place on anonymity decreases.

However, expecting anonymity to relieve every tension created by peer assessment is unrealistic (Panadero & Alqassab, 2019). Panadero and Alqassab (2019)’s literature review on the effects of anonymity in peer feedback shows mixed results, with only a slight positive tendency towards anonymity. Their main conclusions are that more research on the effects of anonymity is needed and that the instructional context and goals need to be considered (Panadero & Alqassab, 2019).

Moreover, anonymity is not always possible in peer feedback (e.g. feedback on an oral presentation), and, even when possible, it is not always desirable. Indeed, anonymity necessarily means that students can not interact with one another and discuss the feedback, which removed the richest part of feedback if we see it as a dialogical process (Ajjawi & Boud, 2017). Additionally, not all potential undesirable effects of the social nature of peer feedback can be cancelled out by the use of anonymity (e.g. the fear of not being able to provide valuable feedback). Therefore, it is necessary to find other ways to create an environment in which students feel safe and comfortable to participate in peer feedback activities.

To ease tensions linked to the social aspects of peer feedback, students could be trained on these aspects. In Li (2017)’s study, for example, students were assigned to three groups: identity group (the identity of assessors and assesses was revealed to each other), anonymity group (both assessors and assesses were anonymous), and the training group (the identities were known, but students followed a training, aimed at controlling the possible negative impact of having their identities revealed). Results indicated that both the training and the anonymity groups showed a larger improvement in their performance than the identity group. Moreover, regarding their perception, students in the training group valued peer assessment activities more and experienced less pressure from peers than the students in the two other groups. Thus, it seems that when anonymity is not feasible, training could counteract the negative impact of having students’ identities revealed.

1.3 Trust and Psychological Safety

Li (2017)’s study suggests that the provision of peer feedback training could be useful, but in her study, she focused on peer pressure, which is not the only important variable linked to the social nature of peer feedback. Based on the literature on collaborative learning and group work, van Gennip and her colleagues (2009; 2010) identified four variables that could be of importance in a peer assessment activity, namely:

-

1.

Psychological safety: the belief shared by members of a group that they can take interpersonal risks in this group

-

2.

Value congruency: the similarities of team members’ opinions about what the tasks, missions and goals of their team should be

-

3.

Interdependence: the fact that everyone needs to participate actively in the assessment task because, if some students do not provide feedback it will have an impact on the students whose work they assessed

-

4.

Trust: (1) the confidence that a student has in his/her own ability to assess their peers’ work—i.e., trust in oneself—and (2) the trust in their peers’ capacity to assess his/her work—i.e., trust in peer

Of these four variables, trust and psychological safety appear to be key to consider when implementing a peer feedback activity. Indeed, van Gennip and colleagues (2012) found that, in the context of secondary-vocational education, a high level of psychological safety and trust (in the self and the peer) had a positive impact on perceived learning. For value congruency and interdependence, the relationship with perceived learning was less clear. Panadero (2016) confirms this: the relevance of trust and psychological safety is more evident than that of value congruency and interdependence, as these two latter variables are relevant in contexts where students have shared goals, which is not necessarily the case in the context of peer feedback (e.g. with online anonymous peer feedback). Consequently, for the training, we focused upon trust and psychological safety.

Regarding the term ‘trust”, it is important to highlight its two facets: trust in oneself and trust in peers (van Gennip et al., 2010). A student can trust his or her ability but not the ability of his or her peers, or vice versa. In a study by Cheng and Tsai (2012), for example, the majority of students (74%) trusted their abilities to assess their peers. A smaller percentage of students (57%) also trusted their peers’ ability.

The notion of psychological safety originally came from organizational psychology where it can be defined as the “perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in a particular context” (Edmondson & Lei, 2014, p. 24). Linked to its origin, the majority of research on psychological safety has been conducted in the working environment (e.g. Edmondson et al., 2007); however, even in the working environment, an emphasis was placed on learning behavior. When people feel psychologically safe, they are less afraid to take interpersonal risks, which means that they are more willing to express themselves without worrying about possible negative reactions from other members of their team. Therefore, in a psychologically safe environment, team members are more willing to carry out learning behavior like seeking feedback, asking for help or talking about errors (Edmondson, 1999). De Stobbeleir and colleagues (2019) confirmed this: when employees perceived their environment as psychologically safe, they seek more feedback from their peers.

In an educational context, Soares and Lopes (2020) have shown that psychological safety has a positive influence on academic performance. Psychological safety creates an environment where students feel comfortable discussing their performance and errors and asking for feedback, which has a positive impact on their learning. Hence, psychological safety is a requirement for peer feedback. In the context of peer assessment, psychological safety is defined by Panadero (2016, p. 251) as “the extent to which students feel safe to give sincere feedback as an assessor and do not fear inappropriate negative feedback as an assessee”.

1.4 Online Training

Online courses, such as MOOCs, have gained popularity over the last decade (Shah, 2020). For such MOOCs, it is challenging to exceed knowledge transfer and provide a real educational experience for students (Suen, 2014). To achieve this and keep the workload for teaching staff feasible, peer feedback is frequently used (Suen, 2014): it allows students to obtain feedback to enhance their learning.

Yet, students’ concerns linked to the social nature of peer feedback may be amplified in MOOC settings. As Suen (2014) explains, peer feedback in MOOCs takes place in a context where there is, at best, few instructor mediation, supervision or guidance and where students have little incentive to take peer feedback activities seriously. In this context, students are often dissatisfied with the use of peer feedback and complain that their peers give them superficial or inconsistent feedback (Hew, 2018). Therefore, taking students' concerns into account and training them before a peer feedback activity could be even more important in MOOCs than in traditional on-campus courses.

1.5 The Present Study

Although some leads exist on how to take into account the interpersonal context when designing peer feedback activities, only a few studies have been conducted (e.g. Rotsaert et al., 2018; Vanderhoven et al., 2015). It remains veiled how trust and psychological safety can be stimulated in an online setting. To fill this gap, we set out to design an online training targeting these two aspects, to optimize students’ learning from peer feedback.

The purpose of this chapter is to present the training and the rationale behind its different components. In the section “Training design”, we will explain how the literature was explored to find effective tools for training. Subsequently, in the section “Training procedure”, a detailed outline of the different stages of the training will be presented. Moreover, even though an evaluation of the training is beyond the scope of this article, we will give some elements on how the training was received by students in the section “Students’ perceptions of the training session”. Finally, we will discuss some limitations and perspectives.

It is important to specify that the training is conceived for peer feedback activities where the feedback are performance feedback, i.e. feedback on students' performance, and not process feedback, i.e. feedback on the way students performed a task (Gabelica et al., 2012). Indeed the training is based on research done on performance feedback and its specific challenges, whose results cannot necessarily be generalized to process feedback (Gabelica et al., 2012).

2 Training Design

2.1 Training Objectives

Our purpose is to design a training to tackle students’ feelings of distrust and psychological unsafety before participating in a peer feedback activity. Given that it is recommended to train students on how to provide peer feedback (van Zundert et al., 2010), we also included a more general part to our training to help students provide effective feedback. Therefore, the training has six objectives:

-

1.

to clarify for the students what the objectives and advantages of peer feedback are

-

2.

to increase students’ skills for providing effective feedback

-

3.

to address students’ concerns about peer feedback

-

4.

to increase students’ feeling of psychological safety

-

5.

to increase students’ trust in their ability to assess others

-

6.

to increase students’ trust in their peers’ ability to assess them

For our two first objectives (objectives 1 and 2) the learning outcomes are knowledge and skills. The learning outcomes of the last four objectives (objectives 3–6) can be considered as attitudes, which are defined as “beliefs and opinions that support or inhibit behavior” (Oskamp, cited by Blanchard & Thacker, 2013, p. 37). Because the training mostly targets students’ attitudes, it must allow the active participation of students. Therefore, the training consisted mainly of role-plays and discussions, two effective methods to transform attitudes (Blanchard & Thacker, 2013).

2.2 Inspirations from Existing Training

As it is common to train students before a peer feedback activity and some training in other contexts than peer feedback may have targeted trust and psychological safety, we additionally explored this literature.

It has been shown that training students before a peer assessment activity improved the reliability of peer assessment, peer assessment skills and students’ attitudes towards peer assessment (van Zundert et al., 2010). Training can focus on various aspects, like how to decide what is important to assess, how to judge a performance or how to provide feedback for future learning (Sluijsmans et al., 2004). Their length may also vary, some of them being very comprehensive (e.g. Sluijsmans et al., 2002), while others are shorter but can still be effective, as shown by Alqassab and colleagues (2018). It is from the latter that we drew to design our training, which we want to keep short enough to fit it into already busy schedules: it seems unrealistic that more than one session will be dedicated to peer feedback training in a course where peer feedback is only a way to help students learn and not an objective in itself.

The training created by Alqassab et al. (2018) consisted of a general discussion on peer assessment, a lecture on Hattie and Timperley (2007)’s framework, group and individual exercises to integrate the theory and practice sessions. Alqassab and colleagues (2018) found that, for medium or high-achieving students, the training increased the proportion of self-regulation feedback, which are considered higher-level feedback and are more effective (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). The training did not affect low-achieving students.

In addition, Dusenberry and Robinson (2020) created a training session to increase students’ feeling of psychological safety before working in small groups. Their training lasted 50 min and was composed of a video lecture, a short discussion and a hands-on exercise. Contrary to their hypothesis, the level of psychological safety was not higher for the students who followed the training than for the students in the control group. They identified several limits in their training, which could explain this absence of a significant effect. A first limitation is that their training was not context-specific. The same training was given to a variety of students, working on various projects, and there was no direct link between the training and the teams’ projects. A second limitation is that the video lecture took up about half of the training time, which did not leave much time for more active learning methods. Consequently, if we want to make sure our training is effective, it seems important to avoid these pitfalls by making our training context-specific and by favouring active learning methods, as also recommended by Blanchard and Thacker (2013).

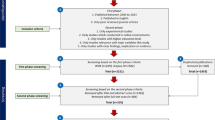

3 Training Procedure

We provided the peer feedback training to third-year university students in physical education following a seminar on acrobatic sports didactics. Forty-one students were enrolled in this mandatory seminar, but six students did not participate in either the training or the peer feedback activity (even though both were mandatory). During this seminar, students had to create an instruction sheet illustrating a gymnastic exercise, assess the instruction sheet of seven of their peers and improve their work based on the feedback they received. The training took place during the second seminar session. It was provided by a researcher (first author) in collaboration with the course’s professor (fourth author). The online training was composed of five stages (see Table 15.1): discovery of student’s representation, lecture on how to provide effective feedback, peer feedback practice, role-play and discussion in small groups, and summary of key learning points.

We conducted the training online, through the Microsoft-Teams platform. Like other videoconferencing applications (e.g. Zoom), Teams allows us to divide participants into break-out rooms, which was essential as most of the training time was spent in subgroups.

Doing the training online incited us to carefully plan it. As Bolinger and Stanton (2020) explained, it is possible to run synchronous online role-plays but the logistics are more difficult to manage. It is not possible, for example, to pass sheets around or to easily identify which students have questions once they are in the break-out rooms. To address these difficulties, we tried to make the instructions as explicit as possible (e.g. what students were expected to do, how much time they had…) and we gave them a very detailed roadmap for the role-plays. We also made sure that there were two instructors present online, which made it possible to visit all sub-groups to answer questions.

As mentioned above, it was challenging to find a balance between the importance of having comprehensive training and the necessity of keeping it time-efficient, so it can be relatively easily inserted into courses. Table 15.1 presents an overview of the training, with the timing devoted to each activity of this two-hour session. As recommended by Blanchard and Thacker (2013), we started by targeting the knowledge and skills before moving on to attitudes.

3.1 Stage 1. Discovery of Students’ Representations

A week before the training session, we asked students to answer some questions through an interactive platform (Wooclap). We asked them to write down in one word what peer feedback means to them, to write down the advantages and disadvantages of peer feedback and to tell us if they had any concerns or fear linked to the use of peer feedback. For the three first questions, students saw the responses of other students appear live and could like them. As an example, Fig. 15.1 is the word cloud generated by students’ answers regarding the disadvantages of peer feedback.

Discovering students’ representations allowed us to tailor the training to this specific group of students, which could enhance training efficiency (Dusenberry & Robinson, 2020). This group of students were concerned that their peers are not qualified enough to assess them, that their peers are not objective enough to assess them (more precisely they fear that they will be “too nice”) and that they themselves are not qualified enough to assess their peers. These results confirmed the relevance of providing a training targeting the notion of trust. Some aspects linked to psychological safety also emerged, although to a lesser extent (e.g. the fear of being judged as stupid).

3.2 Stage 2. Lecture on How to Provide Effective Feedback

At the start of the two-hour training, we explained the six objectives (see Table 15.1) and linked them to students’ concerns based on the Wooclap responses. Then we gave a short lecture on how to provide effective feedback based on the framework of Hattie and Timperley (2007). We explained to students that the purpose of feedback is to reduce the gap between actual and desired performance and it should therefore contain an answer to the three following questions: Where am I going? How am I going? And Where to next? (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). We also described the four feedback levels (self, task, process and auto-regulation), explained why the former two were less effective and gave examples of feedback at each level. The lecture format allowed us to convey essential knowledge to students, but we kept it under 20 min as to not lose students’ attention (Blanchard & Thacker, 2013).

3.3 Stage 3. Peer Feedback Practice

For stage 3, students had the opportunity to practice giving feedback and to familiarize themselves with the rubric they will use afterwards for the real peer feedback activity. The day before the training session, students had to hand in an assignment (similar but not identical to the main assignment). During the training, we paired them in breakout rooms and randomly assigned them two assignments. Students had to individually assess the assignments with a rubric and then, in pairs, compare their assessments and discuss possible disagreements. After returning to the large group, time was set aside for them to ask questions. We also asked them to give examples of feedback they would provide and think together about how to make them as effective as possible.

3.4 Stage 4. Role-Play and Discussion in Small Groups

As explained by De Ketele et al. (2007), role-play is a training method in which participants interpret the role of different characters in a specific situation, to allow an analysis of the representations, feelings and attitudes related to this situation. What distinguishes role-play from other simulations is its emphasis on interpersonal interactions (Bolinger & Stanton, 2020), which makes it particularly relevant for training on trust (in others) and psychological safety.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no existing role-plays on trust and psychological safety in peer feedback described in the literature. Consequently, we designed them ourselves, following general guidelines provided by Bolinger and Stanton (2020). The role-plays’ scenarios were conceived to bring students to project themselves into peer feedback situations and to identify problems that may emerge in these situations. Based on the Wooclap responses (see stage 1), we selected the two most appropriate role-plays among several that we had created. The first role-play consisted of three friends who participated in a peer feedback activity but were all dissatisfied with the received written comments for different reasons (e.g. the feedback were only positive, without any suggestion for improvement). In the second role-play, students had to put themselves in the shoes of three students who had to decide what grade and feedback to give to peers who did a poor oral presentation.

Students were randomly divided into small groups, with each group performing the same role-play simultaneously (i.e. multiple role-plays, Blanchard & Thacker, 2013). This format allowed us to involve all students and to let various elements emerge for the discussion afterwards (given that the scenario will be played slightly different in every group) while taking much less time than if each group had played one after the other (Blanchard & Thacker, 2013).

Once split into groups of six, students received a detailed roadmap with two role-play scenarios and instructions on how to play and discuss them. For each role-play three students acted out the roles while the three others observed the role-play and took notes to inform the following discussion. Having two role-plays allowed each student to play one role, either in the first or second role-play.

After performing and discussing the two role-plays, they stayed in sub-groups to synthesize their discussions. More precisely, we asked them to identify the benefits and interpersonal risks of peer feedback, and what the professor and themselves as students can do to ensure that a peer feedback activity works well.

Participating in role-play simulations can bring discomfort to some students, especially if they are not used to role-playing in class (Bolinger & Stanton, 2020). Therefore, we tried to make the situation as comfortable as possible. Playing in small groups instead of in front of everyone should help students feel at ease. Moreover, by having two role-plays, students more reluctant to participate could observe the first one before actively participating in the second one. And finally, students could choose which role they wanted to play (some roles being more demanding than others).

3.5 Stage 5. Summary of Key Learning Points

The last training stage was an open discussion to synthesize all the sub-groups' ideas in the large group. This method is used to generate participation, find out what participants think or have learned and stimulate recall of relevant knowledge (Blanchard & Thacker, 2013). We asked a student from each group to report the key points of their discussions and took live notes on our slideshow so students could see how the discussion progressed. We used this moment to explain and justify the choices made by the professor for the organization of the peer feedback activity and to link these choices to the elements discussed by students and with the literature on peer feedback. For example, when a student said that they would feel more confident if they were assessed by more than one peer, we explained that this feeling was coherent with the literature (e.g. Sung et al., 2010) according to which when the number of assessors is large enough, peer feedback is as reliable as teacher feedback and that is why they had to provide feedback to seven of their peers for this course (unlike what they did during the training). We also used this moment to address any remaining concerns.

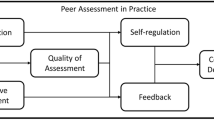

Based on the discussion, we made a mind map (see Fig. 15.2) that we sent to students a few days after the training session. This mind map allows students to keep a record of the key ideas identified together during the training under a visual and accessible format. We also provided them with the slideshow used during the training, for further detail.

4 Students’ Perceptions of the Training

A month after the training session, students answered a short questionnaire to assess it. At this point, students had had the opportunity to transfer knowledge into practice because they had already done the peer feedback activity. Of the 35 students who participated in the training and the peer feedback activity, 27 answered the questionnaire (response rate: 77%). At the end of the questionnaire, students could leave their contact information if they agreed to participate in an interview. We conducted semi-directed interviews with the five students who agreed to participate.

4.1 Questionnaire Conception and Interview Process

We constructed our questionnaire based on Grohmann and Kauffeld (2013)’s Questionnaire for professional training evaluation. This questionnaire is based on Kirkpatrick’s framework (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, cited by Grohmann & Kauffeld, 2013) which distinguishes four levels: reaction, learning, behavior and organizational impact. Grohmann and Kauffeld (2013) have divided the reaction and organizational impact levels into two sub-levels which gives them six subscales (each one composed of two items): satisfaction (reaction level), utility (reaction level), knowledge (learning level), application to practice (behavior level), individual organizational results (organizational level) and global organizational results (organizational level). As the two last subscales are not relevant to our context, we limited our questionnaire to the first four subscales. The eight items of these subscales were subsequently adapted to the higher education context (e.g. the item “In my everyday work, I often use the knowledge I gained in the training” was replaced by “In the peer feedback activity, I used the knowledge I gained in the training”) and translated to French.

In addition, we included four items from Holgado-Tello et al. (2006)’s training satisfaction rating scale, which measures participants’ general impression of the training.

Our questionnaire is therefore composed of 12 items divided into five subscales (see Table 15.2 for details). In line with Grohmann and Kauffeld (2013), we used an 11-points response scale. The responses range from 0 per cent to 100 per cent, with steps of 10 per cent. The general impression scale is reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.854. For the five other subscales, we calculate Spearman-Brown Coefficient, as it is recommended for two-item scales (Eisinga et al., 2013). All scales are reliable, with Spearman-Brown coefficients ranging between 0.752 and 0.929. At the end of the questionnaire, we allowed students to add a written comment.

The interviews were held using Teams and lasted approximately 30 min. We transcribed them and used N-Vivo (version 20.5) to code the data.

4.2 Insights from Questionnaire and Interview Data

As you can see in Fig. 15.3, students’ general impression is generally positive (M = 66.5, SD = 16.4), with the majority of students rating the training around 70%. The satisfaction is a bit lower (see Fig. 15.4), with very high variability (M = 59.3, SD = 20). The same pattern is present for perceived utility (MD = 49.6, SD = 22.5), perceived learning (MD = 53.7, SD = 18.3) and behavioral changes (MD = 55.4, SD = 24) as shown in Figs. 15.5, 15.6 and 15.7.

The most striking result is the high variability of students’ perceptions. For each scale (although to a lesser extent for the general impression), the standard deviation and range are wide, with some students who saw little value in the training (with some aspects evaluated at only 10%) and others who seem to have very positive perceptions of the training (with a score of 90 or 100%).

We see two main reasons for the diversity of students’ perceptions linked to the training. The first concerns variability in students’ needs as illustrated by quotes from David and Robin.Footnote 1

«I want to point out that I was already familiar with the principle of peer feedback because I saw it in Research methodology in Master1. That is why I haven’t learned as much as others, I think.» David (referring to a course in which the peer review process in research is explained; perceived learning: 55, perceived utility: 70).

«Before we had the course I clearly thought that I wasn’t going to be able to… to provide feedback […] and then, with your course, I put this more into perspective, a lot more and I’ll say that I was… I wanted to try and assess my peers, and I could see where I had to go.» Robin (perceived learning: 90, perceived utility: 95).

The variability in students' needs seems to stem from their previous experiences. While most students following this course were in their third year and only followed bachelor courses, some students, like David, were also taking some master courses (based on the number of ECTS they have acquired). Moreover, students also had different extracurricular experiences. Several physical education students had student jobs as sports instructors or coaches, for example, which enable them to develop assessment and feedback skills. Additionally, given that students practice various sports outside their courses, some students have a much higher level than others in acrobatic sports. This high level of expertise could lead them to overestimate their ability to easily provide feedback in this specific discipline. These factors could explain why some students expressed a strong need for guidance, while others felt they already had the necessary knowledge and skills before the training.

Another possible reason concerns the variability in students’ implications in the training session and the seminar more generally. While some students were genuinely interested in the seminar contents, others only followed it because it was mandatory. Given that it was an online session and that students had their cameras off (as not to saturate their wifi), it was more difficult to discern if they were truly paying attention, or if they were even there. In an interview, for example, a student explained that for another session of the course he let his computer with Teams turned on to appear present and went for a run. We tried to make the session as interactive as possible to avoid this, but it is still possible that we lost some students at times.

Moreover, an important part of the training took place in small groups and we observed that some groups worked better than others did in this online context. Indeed, it is well-known that the physical presence of an educator is important for student engagement (e.g. Hunter, cited by Bolinger & Stanton, 2020). The set-up made it difficult for us to know whether the students were taking the role-play seriously and to quickly identify which groups needed help. Although there were two instructors to visit each break-out room, students were just among themselves most of the time and, while most groups seemed to work efficiently, we felt others needed a little push to keep working seriously. This feeling was confirmed by some of the comments in the interviews.

«Well, in the group I was in […] There was some misunderstanding in the group, and we botched the part where we were supposed to take the role.» Raphaël, who liked the training (satisfaction score of 75), but did not feel that it was useful (perceived utility score of 30) or that he learned from it (perceived learning score of 20).

This variation in students’ engagement could explain why some students felt they learned less from the training or said they did not really apply the training content while doing the peer feedback activity.

5 Conclusion and Implications

Our goal was to create an online training to tackle students’ feelings of distrust and psychological unsafety before participating in a peer feedback activity. To this aim, we explored the literature to find effective learning methods. The training that we created was composed of five stages (discovery of students’ representations, theory, practice, role-plays and summary), which allowed students’ active participation. This training was implemented in the context of a physical education university seminar and we collected data on how students perceived it. Based on this, we can draw some conclusions, and stemming from them, implications for practice and perspectives for research.

When given the opportunity students express concerns linked to the social nature of peer feedback. Indeed, the gathered responses showed that, even though students saw various advantages to peer feedback, they also raised a series of concerns, like the fear of not being qualified enough or the fear that their peers will be “too nice” when assessing them. This confirms previous findings (e.g. Mostert & Snowball, 2013; Mulder et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2015) and suggests that, when planning a peer feedback activity, it is essential to take time to let students express these concerns and to address them.

The literature on training methods (e.g. Blanchard & Thacker, 2013) and the studies we drew upon to create the training (e.g. Dusenberry & Robinson, 2020) converged on the idea that (inter)active learning methods are necessary. This training with active learning methods was delivered online, thus making it a potentially useful part of MOOCs (Suen, 2014). For other courses, while normally on campus, online alternatives had to be sought during the COVID-19 outbreak. Indeed, according to UNESCO (2021), more than 220 million tertiary students worldwide have been confronted with university closures and online courses. It is therefore important to conceive learning activities such as role-play that can take place online. In the present case, the group was small enough so we could quickly visit each online break-out room during the sub-groups activities, however, students are generally far more numerous in MOOCs. Future studies should investigate if the training is feasible with larger groups of students.

We obtained encouraging insights when asking students’ opinions about the training. About half the students were positive: they said that they learned from it, found it useful and that it influenced their behavior during the peer feedback activity. Other students valued the training less. Differences in students’ perceptions may be explained by factors like their prior knowledge or experience with peer feedback or by their varying engagement with the training (due to the online context). These factors could be investigated in future studies. We expect students’ perceptions to be less variable if the training is delivered on campus, as physical presence incites engagement (Hunter, 2004, as cited in Bolinger & Stanton, 2020).

The overall positive impact of the training will have to be confirmed in future studies. Indeed, an evaluation study was beyond the scope of this chapter, in which we focused on students’ perceptions of the training. A quasi-experimental study, with a large sample and pre- and post-test should be conducted to verify whether the training has a positive impact on students’ perceived level of trust and psychological safety. In addition, given that the goal of peer feedback is to develop student learning and to incite them to be proactive recipients of feedback, such a study could investigate the impact of the training on students’ learning due to the peer feedback activity, as well as regarding their feedback literacy skills (Boud et al., 2022).

Now the training focuses predominantly on peer feedback provision; its objectives are to teach students how to provide effective feedback and to ensure they feel safe and confident while doing so. A perspective could be to redesign it so it also encompasses peer feedback processing. Indeed, no matter how good the received feedback is, students still need the support of an adequate learning context to efficiently use it to revise their work (Panadero & Lipnevich, 2022; Wichmann, 2018). Given that interpersonal factors—such as trust and psychological safety—play a role in feedback provision, but also in peer feedback processing (Aben et al., 2019), it would be interesting to create an intervention that explicitly considers the social aspects that play a role in peer feedback processing.

All in all, it seems that an online training with (inter)active methods such as role-plays is a promising way to address students’ concerns raised by the social nature of peer feedback.

Notes

- 1.

Names have been changed to protect the participants’ confidentiality.

References

Aben, J. E. J., Dingyloudi, F., Timmermans, A. C., & Strijbos, J. (2019). Embracing errors for learning: Intrapersonal and interpersonal factors in feedback provision and processing in dyadic interactions. In The impact of feedback in higher education: Improving assessment outcomes for learners (pp. 107–125). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_7.

Ajjawi, R., & Boud, D. (2017). Researching feedback dialogue: An interactional analysis approach. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(2), 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863

Alqassab, M., Strijbos, J., & Ufer, S. (2018). Training peer-feedback skills on geometric construction tasks: Role of domain knowledge and peer-feedback levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0342-0

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Blanchard, P. N. & Thacker, J. W. (2013). Effective training. systems, strategies, and practices. Pearson Education Limited.

Bolinger, A. R., & Stanton, J. V. (2020). Role-play simulations. Elgar.

Boud, D., Dawson, P., Yan, Z., Lipnevich, A., Tai, J., & Mahoney, P. (2022). Measuring learners’ capabilities to engage in feedback: The Feedback Literacy Scale [Paper presentation]. EARLI SIG 1 & 4 joint conference 2022, Cadiz, Spain.

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, M., & Lam, J. (2011). Developing sustainable feedback practices. Studies in Higher Education, 36(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075071003642449

Cheng, K., & Tsai, C. (2012). Students’ interpersonal perspectives on, conceptions of and approaches to learning in online peer assessment. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(4), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.830.

De Ketele, J., Chastrette, M., & Cros, D. (2007). Guide du formateur (3e éd. ed.). De Boeck.

De Stobbeleir, K., Ashford, S., & Zhang, C. (2020). Shifting focus: Antecedents and outcomes of proactive feedback seeking from peers. Human Relations, 73(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719828448

Double, K. S., McGrane, J. A., & Hopfenbeck, T. N. (2020). The impact of peer assessment on academic performance: A meta-analysis of control group studies. Educational Psychology Review, 32(2), 481–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09510-3

Dusenberry, L., & Robinson, J. (2020). Building psychological safety through training interventions: Manage the team, not just the project. IEEE Transactions of Professional Communication, 63(3). https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2020.3014483.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Edmondson, A., Dillon, J., & Roloff, K. (2007). Three perspectives on team learning: outcome improvement, task mastery, and group process. In A. Brief, & J. Walsh, J. (Eds.), The academy of management annals, Volume 1. Acad Manag Ann (Vol. 1, pp. 269–314). https://doi.org/10.1080/078559811.

Edmondson, A., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. In Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 23–43). Annual Reviews Inc. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305.

Eisinga, R. N., Grotenhuis, H. F. T., & Pelzer, B. J. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, cronbach or spearman-brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3.

Gabelica, C., Bossche, P. V. D., Segers, M., & Gijselaers, W. (2012). Feedback, a powerful lever in teams: A review. Educational Research Review, 7(2), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2011.11.003.

Grohmann, A., & Kauffeld, S. (2013). Evaluating training programs: Development and correlates of the questionnaire for professional training evaluation. International Journal of Training and Development, 17(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12005

Hanrahan, S., & Isaacs, G. (2001). Assessing self- and peer-assessment: The students’ views. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/07924360120043658

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543029848

Hew, K. F. (2018). Unpacking the strategies of ten highly rated MOOCs: Implications for engaging students in large online courses. Teachers College Record, 120(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811812000107

Holgado Tello, F. P., Chacón Moscoso, S., Barbero García, I., & Sanduvete Chaves, S. (2006). Training satisfaction rating scale: Development of a measurement model using polychoric correlations. European Journal of Psychological Assessment: Official Organ of the European Association of Psychological Assessment, 22(4), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.4.268

Li, L. (2017). The role of anonymity in peer assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(4), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1174766

Mostert, M., & Snowball, J. D. (2013). Where angels fear to tread: Online peer-assessment in a large first-year class. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.683770

Mulder, R. A., Pearce, J. M., & Baik, C. (2014). Peer review in higher education: Student perceptions before and after participation. Active Learning in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787414527391

Panadero, E. (2016). Is it safe? Social, interpersonal, and human effects of peer assessment. In G. T. L. Brown & L. R. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of human and social conditions in assessment (pp. 247–265). Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Panadero, E., & Alqassab, M. (2019). An empirical review of anonymity effects in peer assessment, peer feedback, peer review, peer evaluation and peer grading. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1253–1278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1600186

Panadero, E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2022). A review of feedback models and typologies: Towards an integrative model of feedback elements. Educational Research Review, 35, 100416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100416

Rotsaert, T., Panadero, E., & Schellens, T. (2018). Anonymity as an instructional scaffold in peer assessment: Its effects on peer feedback quality and evolution in students’ perceptions about peer assessment skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0339-8.

Shah, D. (2020). By the numbers: MOOCs during the pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.classcentral.com/report/mooc-stats-pandemic.

Sluijsmans, D. M. A., Brand-Gruwel, S., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Bastiaens, T. J. (2002). The training of peer assessment skills to promote the development of reflection skills in teacher education. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 29(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-491X(03)90003-4

Sluijsmans, D. M. A., Brand-Gruwel, S., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Martens, R. L. (2004). Training teachers in peer-assessment skills: Effects on performance and perceptions. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 41(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1470329032000172720

Soares, A. E., & Lopes, M. P. (2020). Are your students safe to learn? The role of lecturer’s authentic leadership in the creation of psychologically safe environments and their impact on academic performance. Active Learning in Higher Education, 21(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417742023

Suen, H. K. (2014). Peer assessment for massive open online courses (MOOCs). International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 15(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i3.1680.

Sung, Y., Chang, K., Chang, T., & Yu, W. (2009, 2010). How many heads are better than one? The reliability and validity of teenagers' self- and peer assessments. Journal of Adolescence, 33(1), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.004.

Stanier, L. (1997). Peer assessment and group work as vehicles for student empowerment: A module evaluation. Journal of Geography in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098269708725413

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Developing evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

UNESCO. (2021). COVID-19: reopening and reimagining universities, survey on higher education through the UNESCO National Comissions. Retrieved from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378174.

van Gennip, N., Segers, M. S. R., & Tillema, H. H. (2009). Peer assessment for learning from a social perspective: The influence of interpersonal variables and structural features. Educational Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2008.11.002

van Gennip, N., Segers, M. S. R. R., & Tillema, H. H. (2010). Peer assessment as a collaborative learning activity: The role of interpersonal variables and conceptions. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.010.

van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., & van Merriënboer, J. (2010). Effective peer assessment processes: Research findings and future directions. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.004

Vanderhoven, E., Raes, A., Montrieux, H., Rotsaert, T., & Schellens, T. (2015). What if pupils can assess their peers anonymously? A quasi-experimental study. Computers and Education, 81, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.001

Wichmann, A., Funk, A., & Rummel, N. (2018). Leveraging the potential of peer feedback in an academic writing activity through sense-making support. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0348-7

Wilson, M. J., Diao, M. M., & Huang, L. (2015). ‘I’m not here to learn how to mark someone else’s stuff’: An investigation of an online peer-to-peer review workshop tool. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.881980

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020, 2019). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3087–3087. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087.

Yu, F.-Y. Y., & Liu, Y.-H. H. (2009). Creating a psychologically safe online space for a student-generated questions learning activity via different identity revelation modes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(6), 1109–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00905.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Senden, M., De Jaeger, D., Rotsaert, T., Leroy, F., Coertjens, L. (2023). How to Make Students Feel Safe and Confident? Designing an Online Training Targeting the Social Nature of Peer Feedback. In: Noroozi, O., De Wever, B. (eds) The Power of Peer Learning. Social Interaction in Learning and Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-29410-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-29411-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)