Abstract

Providing and receiving feedback requires a certain openness in individuals which is referred to as feedback orientation. Although this openness is also required in peer-feedback processes personal factors that influence student’s openness (i.e. peer-feedback orientation) are less researched. Inspired by feedback orientation studies in a workplace setting we investigated personal factors that influence students’ peer-feedback orientation. As part of an exploratory sequential mixed methods research design, qualitative data on personal factors influencing student’s peer-feedback orientation was collected. Semi-structured interviews with students, teachers and researchers (N = 13) revealed a broad range of personal factors influencing their peer-feedback orientation. Thematic analyses of the data showed that the most prominent factors were related to the perceived usefulness of receiving and providing peer-feedback, the social bond between students, fairness and skills. The importance of existing feedback orientation dimensions (utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy) by (Linderbaum and Levy, Journal of Management 36:1372–1405, 2010) was confirmed in a higher education setting. Interestingly, different interpretations of the dimensions were found which should lead to the development of a peer-feedback orientation scale for higher education.

This work was financed by the Netherlands Initiative for Education Research (NRO), The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science [grant number 405-15-705] (SOONER/http://sooner.nu). https://app.dimensions.ai/details/grant/grant.4120920. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Providing students with personalized feedback is a challenging task for teachers in (open online) higher education (Carless & Boud, 2018). Courses with high student numbers require scalable teaching practices in order to serve the educational needs of students by providing formative feedback and interaction opportunities (Kasch et al., 2017). In an earlier study we identified (online) lectures, students’ self-assessment, peer-assessment and peer-feedback as scalable teaching practices (Kasch et al., 2021a, 2021b). Peer-feedback has a formative function and takes place between two (or more) students. It includes providing and receiving feedback with the goal of supporting the peer in his/her learning process (Topping, 2009). Due to innovation funding on peer-feedback, peer-feedback is more and more explored, implemented and analysed by Dutch universities and higher education institutes (SURF, 2020).

Peer-feedback is a learning method in which students actively engage in so called ‘assessment as learning’ activities either in a face-to-face or online-context. Building on previous definitions of feedback, Carless and Boud (2018) define feedback as a “process through which learners make sense of information from various sources and use it to enhance their work or learning strategies”. We refer to peer-feedback when students provide and receive formative feedback in the context of a learning activity (Huisman et al., 2019). During peer-feedback, both the provider as well as receiver learn with and from each other (Esterhazy & Damsa, 2019). Literature supports that students value both receiving as well as providing peer-feedback (Palmer & Major, 2008; Saito & Fujita, 2004) however, there are also studies reporting mixed results about students’ perceptions (Liu & Carless, 2006; McConlogue, 2015; Nicol et al., 2014; Wen & Tsai, 2006). Regardless of the perceived value, providing and receiving feedback requires student engagement and openness and is a valuable workplace competence (Boud & Molloy, 2013; Carless & Boud, 2018; Huisman et al., 2019). It is influenced by students’ previous peer-feedback experiences. Mulder et al. (2014) point out that students’ beliefs change over time and that the perceived value of peer-feedback decreases after having participated in a peer-feedback activity. Some state that peer-feedback responses and beliefs can be seen as an outcome of a peer-feedback process, meaning that negative experiences have led to negative beliefs and vice versa (Price et al., 2011; van Gennip et al., 2009). Therefore, it is vital to create positive and valuable peer-feedback experiences early on.

Given the educational benefits of peer-feedback and the need to support positive peer-learning experiences, this chapter focuses on personal factors that influence students’ openness to provide and receive peer-feedback (i.e. peer-feedback orientation). As teachers we can support students and increase peer-learning by being aware of personal factors that influence students’ peer-feedback thoughts and behaviour. But currently, there is a research gap regarding personal factors influencing students’ peer-feedback behaviour and a better understanding of individual differences (in higher education) of peer-feedback perception is missing (Dawson et al., 2019; Mulliner & Tucker, 2017; Srichanyachon, 2012; Strijbos et al., 2021; Taghizadeh et al., 2022). Overall research about beliefs and perceptions of feedback mainly focused on the feedback receiver (Alqassab et al., 2019) which is why we know less about the feedback provider (Winstone et al., 2017). Regarding students’ peer-feedback beliefs, Huisman et al. (2019) developed a ‘Beliefs about Peer-Feedback Questionnaire’ (BFPQ). They argue that student’s beliefs relate to the following four themes: (1) valuation of peer-feedback as an instructional method, (2) confidence in own peer-feedback quality, (3) confidence in quality of received peer-feedback and (4) valuation of peer-feedback as an important skill.

Outside educational settings, in the work field and performance management, we see more studies focusing on personal factors influencing feedback processes between employee and employer. In this context, the concept of ‘Feedback Orientation’ (London & Smither, 2002) was proposed which describes an “individuals’ overall receptivity to feedback, including comfort with feedback, tendency to seek feedback and process it mindfully, and the likelihood of acting on the feedback to guide behaviour change and performance improvement” (London & Smither, 2002, p. 81). Linderbaum and Levy (2010) elaborated on their work and developed a ‘Feedback Orientation Scale’ (FOS) which is used to investigate employees feedback orientation (openness towards feedback). Their work is focused on work-related feedback and performance appraisal in the job context. Nonetheless, the maturity of the work and the similarity to peer-feedback has motivated us to build in the authors’ work. Focusing on the feedback receiver (employee), their scale (FOS) consists of four feedback orientation dimensions: utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy (see Table 12.1 right column).

The feedback orientation concept and its translation into four dimensions (FOS) inspired us to use and transfer it to a higher education peer-learning setting. We expect that the four dimensions of the FOS are relevant in a higher education peer-feedback context. Various aspects of these dimensions have been mentioned in earlier feedback related studies (Alqassab et al., 2019; Boud & Molloy, 2013; Carless & Boud, 2018; Hulleman et al., 2008; Latifi et al., 2020, 2021; Patchan & Schunn, 2015). However, scales related to FOS such as the ‘Feedback Environment Scale’ (Steelman & Snell, 2004) or the ‘Instructional Feedback Orientation Scale’ (IFOS) (King et al., 2009) suggest that the context in which feedback orientation is studied influences the factors that can be attributed to it. Given the context of this study, we expect a different interpretation of the dimensions. Therefore, the goal of this study is to investigate if and how the four feedback orientation dimensions (utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy) fit in the context of (higher) education and peer-feedback and if additional dimensions are needed to describe students’ peer-feedback orientation.

Accordingly, the following research questions were investigated:

-

RQ1: Which personal factors are playing a role in students’ peer-feedback orientation (i.e. openness to provide and receive peer-feedback) according to higher education students, teachers and researchers?

-

RQ1a: How can these elements be mapped by the existing feedback orientation dimensions (utility, accountability, social awareness, self-efficacy)?

-

RQ1b: How are utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy interpreted in the context of peer-feedback in higher education?

-

RQ1c: Are additional dimensions needed to map elements that play a role in students’ peer-feedback orientation?

2 Research Design and Method

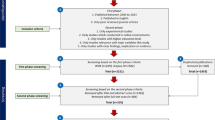

This study is phase 1 of a 2-step-study design (exploratory sequential mixed methods). In a sequential exploratory mixed methods design, first, qualitative data is collected and analysed, followed by quantitative data collection and analysis. Data collection and analyses can take place separately, concurrently or sequentially (Creswell et al., 2011). In this study, data is collected sequentially which means that during the qualitative phase, interview data was collected and analysed to find elements which were used for the development of a quantitative instrument (‘Peer-Feedback Orientation Scale’). This chapter (Fig. 12.1) covers the qualitative data collection, analyses and results while the quantitative part (exploratory factor analysis) is presented in a separate paper (Kasch et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Sequential Exploratory Design applied for this study adapted from Berman (2017). Note Adapted from “An exploratory sequential mixed methods approach to understanding researchers’ data management practices at UVM: Integrated findings to develop research data services.” E. A. Berman, 2017, Journal of eScience Librarianship, 6, p. 6 (https://doi.org/10.7191/jeslib.2017.1098). In “The factor structure of the peer-feedback orientation scale (PFOS): toward a measure for assessing student’s peer-feedback dispositions.” J. Kasch, P. van Rosmalen, M. Henderikx and M. Kalz, 2021, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47, p. 5 (https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1893650)

3 Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Semi-structured interviews were held individually and face-to-face with each participant. An interview protocol was developed and tested beforehand which included a demographics- and a content section. In the demographics section the occupation and peer-feedback experience of the participants were asked. The content section (Table 12.1) started with an open think-aloud phase in which participants were asked to list and explain personal elements that influence their peer-feedback orientation (i.e. openness to provide and receive peer-feedback). Next, participants were presented with the four feedback-orientation-dimensions by Linderbaum and Levy (2010). Without further explanation of their meaning, the participants had to describe and interpret each dimension in the context of peer-feedback. Additionally, we asked them to explain the relevance of the dimensions regarding peer-feedback orientation. Lastly, participants had to assign their previously listed elements to the four dimensions (utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy) and were allowed to add new dimensions if needed. An interview took on average 1 h and was tape-recorded with the permission of the participant. This study was approved by the ethical commission of our university and participation to the study was based on informed consent.

3.1 Participants

A sample (N = 13) of researchers, teachers and students from Dutch universities and higher education institutes participated in the semi-structured interviews. Using a purposeful sampling strategy enabled us to yield perspectives from individuals involved in a peer-feedback process (researchers, teachers and students). We approached teachers from seven research projects who had received a grant from the Dutch Ministry of Education to conduct peer-feedback related practice, four researchers on peer-feedback related research and four students with peer-feedback experience. A gift voucher was given for participation. The 13 semi-structured interviews (nine female and four male) were held within five universities and four universities of applied sciences. The data from five teachers (Amsterdam University, Delft University, Wageningen University, Saxion and HAN University of Applied Sciences), four university researchers and four students (Maastricht University, Open University of the Netherlands and Fontys University of Applied Sciences, Zuyd University of Applied Sciences) were included.

4 Data Analysis

The qualitative data analysis comprised multiple steps:

Transcription of interviews: The tape-recorded interviews were transcribed to prepare them for qualitative analysis by using GOM player (https://www.gomlab.com/). The interview transcripts were entered into N-Vivo 12 Pro for coding (https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products/nvivo-12-pro).

Data coding: The transcripts were then coded using an ‘In-Vivo’ coding method (Saldana 2016). The ‘In-Vivo’ coding method is recommended for studies with the goal to develop new theory about a phenomenon. It is also suitable for novices, since the actual words, phrases and/or sentences of the interviewee are used as codes (Saldana 2016).

Construction of (sub-)themes: The four dimensions of FOS (Linderbaum & Levy, 2010) were guiding during the interviews and the analysis process. However, due to the shift from feedback in a workplace to peer-feedback in an educational setting, this study revisited the interpretation and number of dimensions that play a role in students’ openness, within the perspective of both receiver and provider. The construction of (sub-)themes was done by the first two authors together. The result was presented to and discussed with the third author to produce a final version.

5 Findings

Research Question 1: Which personal factors are playing a role in students’ peer-feedback orientation (i.e. openness to provide and receive peer-feedback) according to higher education students, teachers and researchers?

As mentioned previously, the FOS (Linderbaum & Levy, 2010) and its four dimensions were used as basis for the investigation of students’ peer-feedback orientation. To get insight into the underlying personal factors that could play a role in students’ peer-feedback orientation (RQ1) an open think-aloud interview took place. The findings of this phase show that various personal factors can influence students’ peer-feedback orientation (see Appendix A for a translated list). All participants reported that the bond students have with their peer and the general atmosphere in the group has an influential factor for their orientation. Whilst a positive atmosphere in the group was seen as beneficial for the peer-feedback process, mixed responses were given about the influence of having a positive bond with their peers:

If you like somebody you don't want to run them into the ground and if you don't like somebody at all then maybe you are more inclined to do so.

Students’ confidence about their skills and knowledge were also seen as influential personal factors. The less confident, the more a student can struggle to provide as well as receive feedback. Another element highlighted was the idea of mutuality. Peer-feedback is seen as a give-and-take process and students reported to feel more open if they have the feeling that the other person is putting effort into the provided feedback. However, mutuality seemed to be threatened by other factors such as the hierarchy between students. It was reported that students are more open to receive feedback from a knowledgeable peer than from a less knowledgeable one:

I have groups of seven students and there are good and bad students in them and they all know each other. They know who the good ones are and they know who the bad ones are. And the good ones think, yes, the bad ones don't matter to me, I'm not going to put any energy into them.

If you think that your peer is not as knowledgeable, you are less likely to accept his feedback.

Additionally, students’ prior experience with peer-feedback was highlighted as a factor that can influence students’ orientation. Uncertainty about the procedure and unfamiliarity with the aim of peer-feedback were seen as elements that could negatively influence openness. Students’ feedback needs and readiness to provide and receive peer-feedback were also seen as relevant elements as well as the type of feedback (formative vs. summative) and the moment in which students provide and receive it. It was stated that students are more open to receive formative feedback compared to summative feedback because they are still able to use it for improvement.

If you just started with the task and are not quite ready, receiving feedback can be too much.

The receptivity for feedback will be positively influenced if you know what to expect and if you know that the feedback will be valuable for you.

By revisiting the meaning of the FOS dimensions (utility, accountability, social awareness, self-efficacy), we found first of all, that participants were able to map their generated elements by the FOS dimensions (RQ1a) and secondly, that the dimensions were perceived as relevant in the context of students’ peer-feedback orientation.

Research Question 1b: How are utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy interpreted in the context of peer-feedback in higher education?

Next, participants were presented with the four feedback orientation dimensions by Linderbaum and Levy (2010). Without further explanation of their meaning, the participants had to describe and interpret each dimension in the context of peer-feedback.

We found that the participants interpreted the FOS dimensions in a different way compared to Linderbaum and Levy (2010). Table 12.2 (right column) shows the different ways in which the FOS dimensions were interpreted when discussed in a peer-feedback setting versus a work-related setting (Linderbaum & Levy, 2010).

Transcribing and coding the responses regarding the meaning of the FOS dimensions resulted in a total of 562 codes. Two researchers clustered the 562 codes to meaningful subthemes within each feedback orientation dimension using principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Maguire & Delahunt, 2017). This resulted in 15 subthemes (see Tables 12.2, 12.3 and 12.4). For a more detailed overview of the themes, subthemes and main corresponding codes see Appendix B, C and D.

The subthemes helped to get a better understanding of how the four dimensions were interpreted in the higher-education peer-feedback context (research question 1b). Additionally, the subthemes were needed for the item writing process for the ‘Peer-Feedback Orientation Scale’ in the quantitative part of this study (Kasch et al., 2021a, 2021b).

5.1 Utility

Utility plays an important role for students because they expect to improve from the feedback they receive. For them, utility mainly has to do with receiving new information, new perspectives and the way and the moment they receive the feedback. Formative feedback on draft versions is experienced as more useful than summative feedback on a finished piece where it is no longer possible to use the feedback. Extended feedback containing explanations, comments and discussions is experienced as clear and valuable. Additionally, classroom discussions ensure that students can learn from each other’s cases. It was indicated that students take peer feedback seriously and expect their peers to take it seriously, too. The reciprocity of peer-feedback was mentioned by several participants as well as the need to provide and receive useful feedback in a constructive way. The knowledge level of the student and of peers can also play a role. Insecurity about their knowledge, can result in less openness to provide feedback. The same applies for the timing of feedback and students´ readiness to receive. For example, students who are working on the structure of a piece will perceive feedback on the completeness of content less useful since it does not match their current phase and needs. Additionally, the role of the instructor can influence how students view and deal with feedback. By assessing peer-feedback, giving feedback themselves, or simply checking on the feedback process can influence students’ feedback perceptions and behaviour.

5.2 Accountability

Accountability was described as the sense of responsibility students have regarding their own learning process and that of someone else. Mutual commitment of both parties is important here. Familiarity, friendship and the setting (online or face-to-face) can influence the way students provide and perceive the received feedback. It was also mentioned that there is a difference between ‘good’ and ‘weak’ students and it was claimed that good students take it more seriously. All in all, peer-feedback was described as an unselfish process in which you, as a student, have the goal of being able to help someone else with your feedback.

5.3 Social Awareness

All interviewees agreed that peer feedback is a social process. It takes place in a social context between one or more students and is therefore influenced by a number of (social) elements such as the group feeling, the bond with the group, the position in the group/hierarchy in terms of knowledge but also ranking/popularity. If students feel that the other person is empathetic, yet able to give feedback in an objective way, their openness to receive peer-feedback increases. Being aware of the fact that different perspectives are valid and that in some cases there is no one correct answer, is something students have yet to learn. The instructor should have an advisory role in this regard and lead discussions about different perspectives, which can increase students’ sense of safety. Feeling safe in the way that it is OK to not know ‘the’ answer, to make mistakes, that there is room for discussions and for different perspectives was reported as important in peer-feedback. However, tactical play, favouritism, not being able to get along with each other, are social aspects that can stand in the way of students’ openness.

5.4 Self-efficacy

Participants who were familiar with the term described it as faith in your own abilities. Those who did not know it could identify with this description. Whether students believe in their ability/knowledge or not influences their openness to provide feedback. Participants reported that previous experiences with peer-feedback can influence self-efficacy. Additionally, individual elements such as a student's self-image and self-confidence were also contributed to effect self-efficacy. The peer-feedback context and function (online vs. offline; formative vs. summative) can influence the degree to which students feel safe and thus influences their self-efficacy. To strengthen students’ self-efficacy, instructors need to provide clear expectations and instructions around the peer-feedback process, examples and transparency.

Research Question 1c: Are additional dimensions needed to map elements that play a role in students’ peer-feedback orientation?

Lastly, participants had to assign their previously listed elements to the four dimensions (utility, accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy) and were allowed to add new dimensions if needed.

A small number of participants proposed additional dimensions that could be considered when investigating students’ peer-feedback orientation. These were ‘psychological safety’ (n = 1), ‘personality traits’ (n = 3) and ‘socioeconomic status’ (n = 1). Psychological safety was described as an overarching basic requirement for peer-feedback to be effective. Students need to feel safe in a sense that they know that there is nothing at stake and that others have to follow a code of conduct. A few participants mentioned that personality traits such as being an introvert or extrovert can play a role in students’ openness towards providing and receiving feedback.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

6.1 Discussion

An exploratory sequential mixed methods design was used to explore elements that influence students’ peer-feedback orientation and to investigate whether existing feedback orientation dimensions fit to the higher education peer-feedback context. The findings confirm our expectations, that the four feedback orientation dimensions identified by Linderbaum and Levy (2010) (utility, accountability, social awareness, self-efficacy) are seen as relevant in a peer-feedback context. Additionally, the findings confirm that the four feedback orientation dimensions have another, more broader meaning when applied in a peer-feedback context and that both receiving as well as providing feedback play a role in peer-feedback orientation. The wide range of elements reported by the participants suggests that student’s peer-feedback orientation is influenced by diverse elements such as students´ beliefs about what makes peer-feedback useful and fair. The findings also show that peer-feedback is a complex process and to cover all student elements that underlie students’ peer-feedback orientation is a difficult task.

Related research on students’ peer-feedback perceptions and beliefs, state that student engagement increases if the value of feedback is clear (Moore & Teather, 2013). The findings that students value personal, specific, objective and constructive feedback are also in line with the literature (Dawson et al., 2019; Li & De Luca, 2014). Being confident in their own peer-feedback quality and in the quality of the received peer-feedback was also found by Huisman et al. (2019).

Formative feedback was seen as more valuable for students as opposed to summative feedback since students still have the chance to use the formative feedback to improve their current work. The importance for students to receive timely feedback is shared with previous research on student perceptions (Carless, 2017; Dawson et al., 2019; Pearce et al., 2010). Being able to use feedback in order to improve, supports previous research by Price et al. (2010) who state that feedback on drafts is perceived as more helpful and valuable than feedback on an end product. During the interviews, it was also stated that discussing the received peer-feedback is valued by students and that it can increase their openness to receive and use it. Especially when it comes to written peer-feedback, miscommunication and difficulties with interpreting comments can result in students not using it, which was also reported in other studies (Carless, 2017; Price et al., 2010; Schillings et al., 2021). These barriers can be resolved through discussion and reflection. Additionally, dialogues about feedback and discussing examples increases students’ perceived value of feedback (Price et al., 2010).

Utility was described as the added value of feedback in order to improve and to reaching goals, which is consistent with the study by Linderbaum and Levy (2010). In the workplace context, it was defined by variables regarding work success, skills development, performance improvement and goals reaching (Linderbaum & Levy, 2010). This was also reported by King et al. (2009) who found that in an educational context the perceived utility regarding teacher feedback was based on the motivational factors of teacher feedback, its importance for improvement and students´ tendency to listen to and reflect on teacher feedback.

In this current study, a broader range of variables was identified regarding utility in a peer-feedback context where both the feedback orientation of the receiver as well as the provider were included (e.g. learning with feedback, creating meaning, feedback being tailor made, the moment of receiving and providing feedback, gaining new perspectives, learning from receiving as well as providing). These findings match those of Nicol et al. (2009) who found that students value receiving feedback because it showed them other perspectives and spots for improvement. Similar to King et al. (2009) possible concerns regarding the usefulness of receiving feedback were expressed.

Linderbaum and Levy (2010) defined accountability as “an individual’s tendency to feel a sense of obligation to react to and follow up on feedback” (p. 1377). Although in line with this definition, the results of this study indicated that in peer-feedback, students not only feel responsible to act on the feedback they receive but also for the feedback they provide. Peer-feedback was described as a reciprocal and unselfish process in which students try to support their peers However, it was also stated that some students may have concerns regarding the fairness and seriousness of their peers during the peer-feedback process. Good students were attributed to being more serious than weaker students. In the IFOS by King et al. (2009) accountability is not a separate dimension. A possible explanation might be that teacher feedback is not seen as optional remark on student performance but seen as compulsory expert feedback.

Contrary to the results of Linderbaum and Levy (2010), social awareness was not solely defined by others’ impressions about yourself and how you are perceived by others but rather by the social bond between students and the atmosphere in the group. In a peer-feedback context, social awareness was seen as a very relevant dimension, due to the co-dependency between students being both receiver as well as provider of feedback. Hierarchy between students resulting from differences in domain knowledge and social positioning in the group were stated as relevant factors for the social awareness dimension. In a face-to-face context, social awareness was reported as being higher as opposed to an online context due to the direct contact and relates with the accountability dimension. The IFOS does not contain a social awareness dimension, however their students’ ‘sensitivity’ dimension includes elements that are similar to the findings of this study (i.e. feeling threatened, hurt and stressed by corrective feedback from the teacher) (King et al., 2009). Compared to teacher feedback, peer-feedback makes students co-dependent of each other, which can influence their (social) behaviour and the manner in which they provide feedback.

In the work environment, self-efficacy was defined as “an individual’s tendency to have confidence in dealing with feedback situations and feedback” (Linderbaum & Levy, 2010, pp. 1386). The underlying variables focus on the feedback receivers´ ability to handle, receive and respond to feedback. Again, compared to the FOS (Linderbaum & Levy, 2010), feedback orientation in a peer-feedback context focuses on both the provider as well as the receiver. This distinction is relevant since students’ self-efficacy can vary across tasks (providing vs. receiving) and topics (being more/less knowledgeable in a certain topic). Elements such as fear for criticism, fear of being vulnerable and negative experiences with peer-feedback can negatively influence students’ self-efficacy and thus their openness to receive. A student who is not able to receive feedback because of fear, will likely not see any value in it. Students fear of (corrective) feedback was also described by the feedback sensitivity dimension by King et al. (2009). Although self-efficacy is not a separate scale in the IFOS (King et al., 2009) elements were still included in the form of feedback retention (i.e. student ability to recall and remember teacher feedback).

The findings support the hypothesis that feedback orientation is a universal concept however its implementation is dependent on the context, the parties involved and the function of feedback. Therefore, further investigating the dimensions underlying students’ feedback orientation towards peer-feedback seems relevant and promising. Comparing the findings of this study with related feedback orientation scales (King et al., 2009; Linderbaum & Levy, 2010) appeared complex, given the differences in context (educational vs. work environment), stakeholders (student–student vs. teacher-student vs. employer-employee) and feedback function (mandatory formative peer-feedback vs. corrective teacher feedback vs. developmental feedback). As discussed, the findings of this study are both consistent as well as contrasting compared to the ‘Feedback Orientation Scale’ and the ‘Instructional Feedback Orientation Scale’.

7 Limitations of the Study and Recommendations for Future Research

The major limitation of the study was the small sample size of the participants involved in the research and the limitations to draw the sample only from a Dutch Higher Education context. This decision has been taken for practical reasons, but we might have identified some specific experiences or traits which are especially relevant in this context, but not in others. Future research will need to confirm the findings of this study and the follow-up study (Kasch et al., 2021a, 2021b) to be generalizable beyond the current context.

Additional research will be needed in terms of identifying meaningful differences in students with regard to peer-feedback orientation. While some individual differences can be identified they do not need a differentiated approach for students. At the same time, specific dispositions may need actions which may help students to overcome for example a negative attitude or prior experience with peer-feedback.

8 Conclusions

This paper contributes to the theory development for peer feedback orientation and proposes a new conceptualisation of peer feedback orientation. Based on our findings, students’ peer-feedback orientation relates to providing as well as receiving feedback, the relationship students have with each other and their skills. The findings have been used as a source for the development and testing of a preliminary ‘Peer-Feedback Orientation Scale’, useful for getting insight into students’ dispositions or orientations/openness, towards receiving and providing peer-feedback (Kasch et al., 2021a, 2021b). Being aware and informed about students’ peer-feedback orientation, especially at the beginning of a learning activity, course or even semester can provide teachers with the opportunity to address issues around student perspectives and experiences regarding the utility of providing and receiving peer-feedback, feelings of accountability, social awareness and self-efficacy.

This chapter has provided a documentation of the first step of a 2-step-study exploratory sequential mixed method design with the goal to develop a reliable and valid instrument to measure peer-feedback orientation of students in higher education. The second step of this research has been published already (Kasch et al., 2021a, 2021b). The final goal of the research is to offer options for practitioners to react to individual differences in students regarding their preparedness for peer-feedback activities and to avoid negative experiences with peer-feedback.

References

Alqassab, M., Strijbos, J. W., & Ufer, S. (2019). Preservice mathematics teachers’ beliefs about peer feedback, perceptions of their peer feedback message, and emotions as predictors of peer feedback accuracy and comprehension of the learning task. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 139–154.

Berman, E. A. (2017). An exploratory sequential mixed methods approach to understanding researchers’ data management practices at UVM: Integrated findings to develop research data services. Journal of eScience Librarianship, 6(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7191/jeslib.2017.1098

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Carless, D. (2017). Scaling up assessment for learning: progress and prospects. In D. Carless, S. M. Bridges, C. K. Y. Chan & R. Glofechski (Eds.), Scaling up assessment for learning in higher education (pp. 3–17). Springer Nature.

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a mixed methods design. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2, 53–106.

Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: Staff and student perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

Esterhazy, R., & Damşa, C. (2019). Unpacking the feedback process: An analysis of undergraduate students’ interactional meaning-making of feedback comments. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1359249

Huisman, B., Saab, N., Van Driel, J., & Van Den Broek, P. (2019). A questionnaire to assess students’ beliefs about peer-feedback. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1–11,. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1630294

Hulleman, C. S., Durik, A. M., Schweigert, S. A., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2008). Task values, achievement goals, and interest: An integrative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 398.

Kasch, J., Van Rosmalen, P., & Kalz, M. (2017). A framework towards educational scalability of open online courses. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 23(9), 845–867.

Kasch, J., Van Rosmalen, P., Henderikx, M., & Kalz, M. (2021a). The factor structure of the peer-feedback orientation scale (PFOS): Toward a measure for assessing students’ peer-feedback dispositions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1893650.

Kasch, J., Van Rosmalen, P., & Kalz, M. (2021b). Educational scalability in MOOCs: Analysing instructional designs to find best practices. Computers & Education, 161, 104054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104054

King, P. E., Schrodt, P., & Weisel, J. J. (2009). The instructional feedback orientation scale: Conceptualizing and validating a new measure for assessing perceptions of instructional feedback. Communication Education, 58(2), 235–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520802515705

Latifi, S., Noroozi, O., Hatami, J., & Biemans, H. J. A. (2021). How does online peer feedback improve argumentative essay writing and learning? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1687005

Latifi, S., Noroozi, O., & Talaee, E. (2020). Worked example or scripting? Fostering students’ online argumentative peer feedback, essay writing and learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1799032

Liu, N. F., & Carless, D. (2006). Peer feedback: The learning element of peer assessment. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(3), 279–290. http://hdl.handle.net/10722/54282.

Linderbaum, B. A., & Levy, P. E. (2010). The development and validation of the Feedback Orientation Scale (FOS). Journal of Management, 36(6), 1372–1405.

Li, J., & De Luca, R. (2014). Review of assessment feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 378–393.

London, M., & Smither, J. W. (2002). Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Human Resource Management Review, 12(1), 81–100.

McConlogue, T. (2015). Making judgements: Investigating the process of composing and receiving peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 40(9), 1495–1506.

Moore, C., & Teather, S. (2013). Engaging students in peer review: Feedback as learning. Issues in Educational Research, 23(2), 196–211.

Mulder, R. A., Pearce, J. M., & Baik, C. (2014). Peer review in higher education: Student perceptions before and after participation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 15(2), 157–171.

Mulliner, E., & Tucker, M. (2017). Feedback on feedback practice: Perceptions of students and academics. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(2), 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1103365

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.795518

Palmer, B., & Major, C. H. (2008). Using reciprocal peer review to help graduate students develop scholarly writing skills. The Journal of Faculty Development, 22(3), 163.

Patchan, M. M., & Schunn, C. D. (2015). Understanding the benefits of providing peer feedback: How students respond to peers’ texts of varying quality. Instructional Science, 43(5), 591–614.

Pearce, J., Mulder, R., & Baik, C. (2010). Involving students in peer review: Case studies and practical strategies for university teaching. http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/resources_teach/teaching_in_practice/docs/Student_Peer_Review.pdf.

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., & O'donovan, B. (2010). Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 277–289.

Price, M., Handley, K., & Millar, J. (2011). Feedback: Focusing attention on engagement. Studies in Higher Education, 36(8), 879–896.

Saito, H., & Fujita, T. (2004). Characteristics and user acceptance of peer rating in EFL writing classrooms. Language Teaching Research, 8(1), 31–54.

Schillings, M., Roebertsen, H., Savelberg, H., van Dijk, A., & Dolmans, D. (2021). Improving the understanding of written peer feedback through face-to-face peer dialogue: Students’ perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(5), 1100–1116. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1798889

SURF. (2020). Stimuleringsregeling Open Online Onderwijs. https://www.surf.nl/en/node/2511.

Srichanyachon, N. (2012). An investigation of university EFL students attitudes toward peer and teacher feedback. Educational Research and Reviews, 7(26), 558–562.

Steelman, L. A., Levy, P. E., & Snell, A. F. (2004). The feedback environment scale: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(1), 165–184.

Strijbos, J. W., Pat-El, R., & Narciss, S. (2021). Structural validity and invariance of the feedback perceptions questionnaire. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 68, 100980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.100980

Taghizadeh Kerman, N., Noroozi, O., Banihashem, S. K., Karami, M. & Biemans, H. H. J. A. (2022). Online peer feedback patterns of success and failure in argumentative essay writing. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2093914.

van Gennip, N. A., Segers, M. S., & Tillema, H. H. (2009). Peer assessment for learning from a social perspective: The influence of interpersonal variables and structural features. Educational Research Review, 4(1), 41–54.

Wen, M. L., & Tsai, C. C. (2006). University students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward (online) peer assessment. Higher Education, 51(1), 27–44.

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Parker, M., & Rowntree, J. (2017). Supporting learners’ agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educational Psychologist, 52(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2016.1207538

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A

List of (personal) elements that influence students’ openness to provide and receive peer-feedback provided by interviewees (N = 13) during think-aloud part of a semi-structured interview.

Interviewee | Elements influencing students’ openness to provide and receive peer-feedback |

|---|---|

Student 1 | • Feedback previously received from the teacher • Amount of time invested in the task (on which you will receive feedback) • Self-confidence • Getting on well with the other students of the peer-feedback group • Providing positive feedback to receive positive feedback as well |

Student 2 | • Being afraid to hurt the other person • Feeling unsecure to provide feedback • Feeling unsecure to receive feedback • Providing feedback in an objective way |

Student 3 | • Attitude of peer-feedback receiver • Group context/structure • Confidence • New feedback • The way you receive and provide feedback • Having specific moments were you provide and receive feedback • Mutual effort in providing feedback • Explaining feedback |

Student 4 | • Own knowledge • Justified feedback • Knowledge level of feedback provider • Boosting participation score • Relationship with the other person • Confidence level of feedback provider |

Teacher 1 | • Introvert • Experience with peer-feedback • Factual knowledge • Tactical game between students • Ratio of knowledge in the group • Atmosphere in the group |

Teacher 2 | • Uncertainty about the procedure • Fear of criticism • Uncertainty over content knowledge |

Teacher 3 | • Life experience/maturity • Self-confidence in providing and receiving peer-feedback • Previous experience with peer-feedback (in a formal and informal way) • Familiarity with the scientific process of peer-review • Social sensitivity (introvert/extrovert) |

Teacher 4 | • Self-image • Self-confidence • Alleged knowledge in the field in question • Number of siblings • Position in the group/class • Emotional age/matureness • Experienced consequences of the peer-feedback activity • Sex • Language skills • Previous experience with peer-feedback • Mood • Cultural background • Extrovert/introvert |

Researcher 1 | • Familiarity with the peer • Position in the group • Being open-minded and receptive • Working one-on-one or in a group • Character from the peer • Culture • Safe environment • Expertise of the peer • Hierarchy • Mental state • Moment of the learning process • Feedback on the task vs. feedback on the process • Summative vs. formative feedback • Reliability of the feedback • Quality of the work one has to review • Added value for own learning • Amount of feedback one is receiving |

Researcher 2 | • Self-awareness • Judgement of learning • Confidence • Positive attitude • Perseverance • Time to be spent on peer-feedback • Formative way • Personality (introvert/extrovert) • Curiosity/eagerness to learn • Trust in others • Knowledge level • Sex • Perfectionism |

Researcher 3 | • Need for structure, expectations and a clear goal • Self-confidence • Unfamiliarity with the group • Negative association with peer-feedback • Previous experiences with peer-feedback • Motivation • Interactivity (social skills) • Content knowledge |

Researcher 4 | • Previous experience, both positive and negative with peer-feedback • Whether the feedback meets your needs or not • Self-image about yourself as a human being • Self-image about your knowledge and skills • Your state of being/ current mood • Your strength • Your view of the other persons’ knowledge and skills • Your opinion about the other person |

Appendix B

Themes, subthemes and the main corresponding codes (originally in Dutch and translated for publication).

Theme: Utility | Theme: Accountability | Theme: Social Awareness | Theme: Self-efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

Subtheme: Teacher role Teacher control Equivalency student and teacher feedback Grading feedback Subtheme: Learning with feedback Feedback on the process Aimed at the receiver Getting another perspective Added value of feedback Learning from each other Subtheme: Feedback is tailor-made Insecurity about own knowledge Needs of receiver and provider Being ready to receive Receiving too much Content related and constructive feedback Providing value Being able to recognize value What happens next? Subtheme: Creating meaning Same frame of reference Familiarity with the scientific process Explaining feedback Small groups Goal of feedback Subtheme: Feedback moment Feedback on completed work Feedback on draft version Time to use feedback Several feedback moments | Subtheme: Influence of the process on your accountability Being approachable Talking about feedback Uncertainty about the feedback process Teacher making students feel accountable Subtheme: Things you hold the other accountable for Reciprocity Benefitting from my feedback Responsible for own learning process Familiarity of the peer Taking peer-feedback seriously Subtheme: Things you hold yourself accountable for Trust in your own abilities Unselfish Responsible for own learning process Doing something with the feedback | Subtheme: On a group level Higher in face-to-face Trust in the feedback provider Position in the group Subtheme: Behaviour that contributes positively to social awareness Empathise Balance between tips and tops Being open to different points of view Psychological safety Subtheme: Behaviour impairing social awareness If you can get along with the other person Other person is benefitting from my work Tactical moves Anonymity | Subtheme: Your role as a giver Feeling competent to add something Time investment Feedback on your feedback The way you receive feedback Subtheme: Your role as a receiver Fear for criticism Wanting to receive feedback Previous experiences Testing whether feedback is justified There is no black and white answer Being vulnerable Being able to process feedback Subtheme: Self-efficacy for giver and receiver Having enough content knowledge Self-image Self-confidence Subtheme: Context prerequisites for self-efficacy Transparency of the process Feedback as a skill Training peer-feedback |

Appendix C

Percentage distribution of all peer-feedback orientation themes.

Appendix D

Frequencies and percentages of the peer-feedback orientation themes and corresponding subthemes.

Within a subtheme | Across all subthemes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Peer-Feedback Orientation (Sub-)Themes | Frequency | Relative Frequency | % | Relative Frequency | % |

Utility | |||||

Definition | 16 | 0.080 | 8 | 0.028 | 3 |

Subtheme 1 ‘Teacher role’ | 43 | 0.215 | 22 | 0.077 | 8 |

Subtheme 2 ‘Learning with feedback’ | 47 | 0.235 | 24 | 0.084 | 8 |

Subtheme 3 ‘Feedback is tailormade’ | 39 | 0.195 | 20 | 0.069 | 7 |

Subtheme 4 ‘Creating Meaning’ | 36 | 0.180 | 18 | 0.064 | 6 |

Subtheme 5 ‘Feedback Moment’ | 19 | 0.095 | 10 | 0.034 | 3 |

Total | 200 | 1.000 | 100 | 0.356 | 36 |

Accountability | |||||

Definition | 17 | 0.163 | 16 | 0.030 | 3 |

Subtheme 1 ‘Influence of the process on your accountability’ | 19 | 0.183 | 18 | 0.034 | 3 |

Subtheme 2 ‘Things you hold the other accountable for’ | 49 | 0.471 | 47 | 0.087 | 9 |

Subtheme 3 ‘Things you hold yourself accountable for’ | 19 | 0.183 | 18 | 0.034 | 3 |

Total | 104 | 1.000 | 100 | 0.185 | 19 |

Social Awareness | |||||

Definition | 13 | 0.115 | 12 | 0.023 | 2 |

Subtheme 1 ‘On a group level’ | 41 | 0.363 | 36 | 0.073 | 7 |

Subtheme 2 ‘Behaviour that contributes positively to social awareness’ | 36 | 0.319 | 32 | 0.064 | 6 |

Subtheme 3 ‘Behaviour imparing social awareness’ | 23 | 0.204 | 20 | 0.041 | 4 |

Total | 113 | 1.000 | 100 | 0.201 | 20 |

Self-efficacy | |||||

Definition | 12 | 0.111 | 11 | 0.021 | 2 |

Subtheme 1 ‘Your role as a giver’ | 16 | 0.148 | 15 | 0.028 | 3 |

Subtheme 2 ‘Your role as a receiver’ | 30 | 0.278 | 28 | 0.053 | 5 |

Subtheme 3 ‘Self-efficacy for giver’ | 31 | 0.287 | 29 | 0.055 | 6 |

Subtheme 4 ‘Context/prerequisites for self-efficacy’ | 19 | 0.176 | 18 | 0.034 | 3 |

Total | 108 | 1.000 | 100 | 0.192 | 19 |

Other | 37 | 1.000 | 100 | 0.066 | 7 |

Total all | 562 | ||||

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kasch, J., van Rosmalen, P., Kalz, M. (2023). A Thematic Analysis of Factors Influencing Student’s Peer-Feedback Orientation. In: Noroozi, O., De Wever, B. (eds) The Power of Peer Learning. Social Interaction in Learning and Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-29410-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-29411-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)