Abstract

This chapter focuses on the role of imaging, in particular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), for the evaluation of patients with cervical cancer (CC) and endometrial cancer (EC).

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

FormalPara Learning Objectives-

Describe the role of MRI and FDG-PET to guide the management of patients with CC and EC.

-

Highlight Tailored MRI Protocols for Staging of CC and EC

-

Emphasize the advantages and limitations of MRI and FDG-PET in the evaluation of patients with CC and EC.

-

Explain the role of imaging to confirm eligibility for fertility-sparing management.

14.1 Part I: Cervical Cancer

14.1.1 Epidemiology

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most frequent malignancy in women worldwide with majority of new cases and deaths occurring in low-to-middle-income countries [1]. Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection causes most CC. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus also increases the risk of CC [2]. CC can be prevented with HPV vaccination, HPV DNA testing, and timely treatment of pre-cancerous lesions [1, 3].

14.1.2 Presentation and Diagnosis

Patients may have no symptoms or present with vaginal bleeding, discharge, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 70–80% and adenocarcinoma for 20–25% of CC [4].

14.1.3 Staging

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification is used to stage CC [5]. The latest 2018 revision contains several key updates [5]. Pathologic and imaging findings can be used to supplement clinical findings, allowing the inclusion of lymph node (LN) status into the staging system. A notation (r for imaging, p for pathology) is added to indicate the method that was used to assign the stage. Pathologic findings take precedence over clinical exams and imaging. Stage IB is now divided into three subgroups (instead of two), IB1 ≤ 2 cm, IB2 > 2 cm to ≤4 cm, and IB3 > 4 cm, better capturing superior oncologic outcomes and potential for fertility-sparing treatment in patients with tumors ≤2 cm [6]. Stage III now includes Stage IIIC with IIIC1 indicating pelvic and IIIC2 para-aortic LN metastases.

Key Point

-

The 2018 FIGO staging system allows pathologic and imaging findings to supplement clinical findings to assign the stage.

14.1.4 Management

Surgery (simple or radical hysterectomy) is advised for patients with cervix/upper vagina-confined tumors ≤4 cm [4, 7]. Fertility-sparing approach (conization, simple or radical trachelectomy) is an option for women who desire fertility and have cervix-confined tumors ≤2 cm. Parametrial resection differentiates radical from simple hysterectomy or trachelectomy. Pelvic LN assessment is added to the above procedures, with sentinel LN mapping favored over traditional lymphadenectomy [4, 7].

Chemoradiotherapy is preferred to surgery for cervix/upper vagina-confined tumors >4 cm [4, 7]. Chemoradiotherapy is also recommended for locally advanced disease, i.e., parametrial invasion and beyond (regardless of tumor size) but no distant metastases. External beam radiation is delivered concurrently with platinum-based chemotherapy followed by image-guided brachytherapy. Patients presenting with distant metastases are managed with systemic chemotherapy and, if needed, targeted radiation.

14.1.5 Role of Imaging in Initial Staging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows to optimally assess loco-regional tumor extent and, if applicable, confirm eligibility for fertility-sparing surgery [8, 9]. MRI protocol should be tailored as described in Table 14.1 [8]. Patients are asked to empty their bladder and bowel before the exam to optimally position the uterus and minimize rectal gas. Anti-peristaltic agents can reduce bowel motion.

High-resolution small field-of-view T2-weighted images (T2WI) in sagittal and oblique axial planes (Table 14.1 and Fig. 14.1) are essential to local staging [8]. CC has intermediate-SI compared to low-SI cervical stroma on T2WI (Fig. 14.2). Diffusion-weighted images (DWI) [typical b values of 0–50 and 800–1000 s/mm2] are acquired using the same plane, field-of-view, and slice thickness as T2WI. Tumor demonstrates high-SI on high b-value DWI and low-SI on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map (Fig. 14.2). Side-by-side review of T2WI and DWI is useful to determine tumor margins and assign FIGO stage [8]. Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging (DCE) is primarily a research tool and is not essential in routine clinical practice [8].

A diagram illustrating relevant anatomy of the uterine corpus and cervix. Parametrial regions are comprised of connective tissues suited lateral to the cervix. On sagittal images, the location of internal os is identified as the narrowing of the endocervical canal superiorly before it widens again as endometrial cavity. On oblique axial images, the location of internal os is indicated by the entrance of uterine vessels

39-year-old patient with squamous carcinoma of the cervix. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted image shows a 4.5 cm intermediate-SI tumor infiltrating entire cervical stroma. A dashed line indicates the orientation of oblique axial plane. B, C, and D. Oblique axial T2WI (b), DWI (c), and ADC map (d) demonstrate intermediate-SI tumor on T2WI with diffusion restriction (high-SI on high b-value DWI and low-SI on ADC map), full-thickness cervical stromal invasion and spiculated tumor-parametrial interface (arrows). (e) Axial T2WI image shows an enlarged (12 mm in short axis) right external iliac lymph node (arrowhead) and non-enlarged left external iliac lymph node. (f) Axial FDG-PET/CT image shows FDG avid right external iliac lymph node consistent with metastatic adenopathy

Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET) is advised for patients with cervix-confined tumors >4 cm and higher stage disease [7]. FDG-PET can be fused to either CT or MRI.

Key Point

-

MRI is essential to determine loco-regional tumor extent and confirm eligibility for fertility-sparing surgery.

-

FDG-PET facilitates the detection of LN and distant metastases.

Stage I: Cervix-confined disease [extension to the uterine corpus is disregarded].

Stage IA is microscopic in size and, thus, below the imaging resolution. Stage IB includes IB1 ≤ 2 cm, IB2 > 2 cm to ≤4 cm, and IB3 > 4 cm based on the greatest tumor diameter [5]. The tumor can be measured in any plane that best demonstrates its maximum size. Intact rim of low-SI cervical stroma around intermediate-SI tumor on oblique axial T2WI excludes parametrial invasion [8, 9]. Combined review of T2WI and DWI may help to better delineate tumor margins and to distinguish tumor from post-procedural edema/inflammation. The latter has intermediate-SI on T2WI mimicking tumor but should not show diffusion restriction [8].

Women of childbearing age may be eligible for fertility-sparing management if they have cervix-confined tumors ≤2 cm of squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma histology that are located ≥1 cm inferior to the internal os (Fig. 14.1) [4, 7].

Stage II: Tumor is limited to the upper vagina (IIA) or parametrial regions (IIB).

The involvement of upper two-thirds of the vagina (Stage IIA) is divided into IIA1 (≤4 cm) and IIA2 (>4 cm) disease [5]. If a horizonal line is placed at the bladder neck, the upper vagina is located above and the lower vagina is situated below this line (Fig. 14.1) [8, 9]. Vaginal involvement is suspected when intermediate-SI tumor interrupts low-SI vaginal wall.

Full-thickness cervical stromal invasion (replacement of low-SI cervical stroma by intermediate-SI tumor) on T2WI does not indicate parametrial invasion (Fig. 14.3). The diagnosis of parametrial invasion (Stage IIB) requires a nodular or spiculated tumor-parametrial interface in addition to full-thickness cervical stromal invasion (Fig. 14.2) [8, 9]. Tumor may also encase parametrial vessels. Adding DWI to T2WI does not change sensitivity for parametrial invasion (68–89%) but improves specificity from 85–89% to 97–99% [10].

A schematic of oblique axial images through the cervix. Full-thickness cervical stromal invasion does not indicate parametrial invasion. The diagnosis of parametrial invasion requires a nodular or spiculated tumor--parametrium interface in addition to full-thickness cervical stromal invasion. Tumor with parametrial regions may also encase parametrial vessels

Stage III: Tumor involves lower third of vagina (IIIA), extends to pelvic wall and/or causes hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney (IIIB), or involves pelvic and/or para-aortic LNs (IIIC) [including micro-metastases].

Pelvic wall invasion is present when the tumor extends within 3 mm or directly abuts pelvic wall muscles or iliac vessels [8, 9]. Stage IIIC has been added in 2018 with IIIC1 denoting pelvic and IIIC2 para-aortic LN metastases [5].

LN metastases impact prognosis and, thus, treatment choice. MRI has moderate sensitivity (51–57%) and high specificity (90–93%) for LN metastases [11,12,13]. Short axis diameter ≥1 cm is the main criterion, although ancillary features like round shape, heterogenous-SI, same SI as primary tumor, LN clustering, and necrosis may help to identify small LN metastases (Fig. 14.2). Both benign and malignant LNs have high-SI on high b-value DWI making them easy to see. The ADC cut-off values are not used to identify LN metastases because mean ADCs of benign and malignant LNs overlap [8].

FDG-PET has both high sensitivity (88%) and specificity (93%) for pelvic LN metastases (Fig. 14.2) [14]. Detection of para-aortic LN metastases is less robust (sensitivity 40%, specificity 93%) due to low prevalence and small size [14].

Stage IV: Tumor invades bladder/rectal mucosa [biopsy-proven] (IVA) or shows distant metastases (IVB).

Bladder/rectal mucosal invasion (stage IVA) is present when intermediate-SI tumor disrupts low-SI bladder/rectal wall and extends into the edematous (bullous) mucosa or the lumen on T2WI [15]. Bullous edema alone is insufficient to assign stage IVA.

Stage IVB indicates distant metastases including LN metastases beyond pelvic and para-aortic regions. FDG-PET is the optimal approach to detect distant spread [16]. A biopsy confirmation is required due to the potential for false positives.

Key Point

-

The diagnosis of parametrial invasion requires a nodular or spiculated tumor-parametrial interface in addition to full-thickness cervical stromal invasion.

-

Bullous edema alone is insufficient to assign Stage IVA.

14.1.6 Assessment of Treatment Response During and After Treatment

Pre-treatment MRI and FDG-PET facilitate chemoradiotherapy planning. Mid-treatment pre-brachytherapy MRI allows dose adjustment based on residual tumor volume to maximize local control and minimize adjacent organ dose [17]. Pretreatment mean ADC does not predict response to chemoradiotherapy, but tumor regression rate and the change in mean ADC values during treatment may inform response [18, 19].

Post-treatment MRI and FDG-PET are usually obtained 6 months after chemoradiotherapy. Reconstitution of low-SI cervical stroma on T2WI suggests tumor-free cervix, but edema/inflammation can persist 6–9 months post treatment [8, 9]. Post-treatment FDG-PET informs prognosis with partial response (FDG avidity reduced from baseline) indicating moderate recurrence risk and progressive disease (unchanged, increased, or new foci of FDG avidity) suggesting persistent tumor [20].

14.1.7 Evaluation of CC Recurrence

Most patients recur within 2 years of initial treatment [8, 9]. Imaging characteristics of the recurrent disease are the same as primary tumor. MRI and FDG-PET allow a comprehensive assessment of tumor extent [21]. Chemotherapy is advised for localized recurrence after surgery. Radical surgery (pelvic exenteration) is the potential salvage option post chemoradiotherapy.

14.1.8 Future Directions

PET/MRI may offer a “one-stop shop” approach by providing anatomic, functional, and metabolic information in one exam [8]. Studies are needed to validate the added value of PET/MRI beyond the convivence of a single imaging session.

14.2 Part II: Endometrial Cancer

14.2.1 Epidemiology and Diagnosis

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the third most common malignancy in women worldwide and the most common gynecological cancer in developed countries [1]. The majority of cases are diagnosed at an early stage (70% stage I) with a 5-year survival rate of more than 95% [22]. While postmenopausal women are predominantly affected (75% are >50 years), 4% of the women diagnosed with EC are younger than 40 years, and therefore preservation of fertility is an important consideration [23].

Patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding are initially evaluated by transvaginal ultrasound. In postmenopausal patients, a focal or diffuse endometrial thickening of >4–5 mm is considered suspicious and should be followed by an endometrial pipelle or hysteroscopy and biopsy [24].

14.2.2 Histopathological Subtypes

There are two main histological subtypes. Type I (80–85%) is estrogen-dependent, affects younger patients, and has a good prognosis. Type II (10–15%) is not estrogen driven, affects older women, behaves more aggressively, and has a poorer prognosis (5-year survival rate of 40%) [24]. Most cases of EC are sporadic, although 5% have a hereditary component linked to hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) [25]. Histologically, type I is a grade 1 or 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma; type II includes grade 3 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear-cell carcinoma, undifferentiated, serous carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma. More recently, the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research working group, introduced four molecular subtypes that relate to prognosis: (1) POLE (ultra-mutated tumors), (2) microsatellite unstable tumors, (3) copy-number high tumors with mostly TP53 mutations, and (4) copy-number low tumors without any of the above alterations, reflecting the profound genomic heterogeneity of EC [26].

14.2.3 Role of Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging modality to evaluate patients with newly diagnosed EC [27]. MRI findings facilitate risk assessment and ultimately guide treatment choice and surgical planning. The combination of T2WI, DWI, and DCE provides the “one-stop shop” approach [27]. The high-resolution T2WI is angled perpendicularly to the endometrium to obtain oblique axial images (Fig. 14.1). These are essential for accurate assessment of the depth of myometrial invasion (MI). A slice thickness of 4 mm and the use of non-fat suppressed sequences is advised [27]. DWI are obtained with a minimum of two b values of 0–50 and 800–1000 s/mm2 in the same orientation as the sagittal and oblique axial T2WI (Table 14.1). MRI protocol for EC patients should also include a large-field-of-view axial T1WI and/or T2WI images of the pelvis and abdomen to identify enlarged lymph nodes, hydronephrosis, and bone marrow changes [27]. CT and PET/CT improve the evaluation of LN and distant metastases; PET/CT is currently not part of the standard-of-care for the initial staging of EC. However, it plays a crucial role in treatment selection and planning of pelvic exenteration in patients with tumor recurrence [21].

Key Points

-

The combination of T2WI, DWI, and DCE provides the “one-stop shop” approach to the staging of EC.

14.2.4 MRI Indications

MRI has an essential role in treatment planning by (1) establishing the origin of the tumor and (2) assessing the local extent of the disease [9, 28]. The origin of the tumor is routinely established through clinical examination and histologic evaluation of biopsy specimens. However, in a limited number of cases, it is difficult to determine the tumor’s origin due to, for example, unusual morphologic patterns, mixed-type histologic findings, or inadequate samples. Differentiating between endometrial and cervical origin is critical as it has major implications for patient management [29]. Most ECs are treated with simple hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, while CC patients undergo simple or radical hysterectomy in early stage and chemoradiotherapy in advanced disease [4, 7]. MRI has been proved useful in this clinical scenario, with an accuracy of 85–88% in correctly attributing the cancer origin to the corpus or cervix [9].

MRI has a reported accuracy of 85–93% in delineating the extent of the EC and is the imaging modality of choice to determine the depth of myometrial invasion preoperatively [9, 27, 28]. The latter is the most important morphologic prognostic factor, correlating with tumor grade, presence of LN metastases and overall survival [9, 27, 28]. Special attention should be given to the eligibility criteria prior to the fertility-sparing treatment for patients with grade 1 EC who desire fertility preservation. In these patients, MRI is crucial for confirming the absence of myometrial invasion, cervical stroma invasion, ovarian metastases, and lymphadenopathy.

Key Point

-

MRI is crucial to confirm endometrium-confined disease prior to fertility-sparing management.

14.2.5 MRI Features of EC

On T2WI, EC appears as a thickened endometrium or a mass, occupying the endometrial cavity. It shows hyperintense SI when compared to hypointense myometrium, and intermediate-low SI relative to hyperintense normal endometrium (Fig. 14.4). Small tumors may not be associated with endometrial thickening or can have a similar SI to that of normal endometrium. In these cases, DWI and DCE are particularly helpful. On DWI, the tumor is hyperintense on high b-value images (800–1000 s/mm2), with a corresponding hypointense SI on the ADC map (Fig. 14.4). On DCE images, the tumor shows an early enhancement compared to normal endometrium and on later phases it appears hypointense relative to the myometrium.

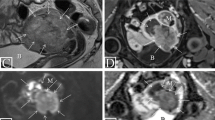

“One-stop shop” approach, FIGO stage II endometrial cancer. A 66-year-old patient with vaginal bleeding. On T2WI there is an intermediate-SI endometrial tumor (a), which interrupts the low-SI of cervical stroma (b, arrow). On DCE (c) the normal enhancement of cervical stroma is disrupted by the hypo-enhancing tumor (arrow) which has restricted diffusion on DWI (d, arrow). The gross examination of the surgery specimen shows the solid tumor (e, arrow). The pathology revealed endometrioid adenocarcinoma involving the cervical stroma (f), consistent with FIGO stage II. These images were originally published in Pintican R, Bura V, Zerunian M, Smith J, Addley H, Freeman S, Caruso D, Laghi A, Sala E, Jimenez-Linan M. MRI of the endometrium—from normal appearances to rare pathology. Br J Radiol. 2021 Sep 1; 94 (1125): 20201347. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20201347. Epub 2021 Jul 8. PMID: 34233457; PMCID: PMC9327760

14.2.6 EC Staging with MRI

Endometrial cancer staging is usually performed using FIGO classification [30].

Stage I: Tumor invasion of < 50% of the myometrial thickness indicates a stage IA tumor, while the invasion of ≥ 50% of the myometrial thickness indicates a stage IB tumor (Fig. 14.5). There are several pitfalls such as tumor extension into cornua, presence of adenomyosis and leiomyomas (Table 14.2) [9, 27, 28]. In such cases, DWI and DCE help better delineate the tumor margins and lead to improved accuracy.

Stage II: Tumor invades the cervical stroma. The hyperintense SI inflammation (edema) within cervical stroma on T2WI may lead to up-staging. The presence of intermediate T2 SI tumor with diffusion restriction and hypo-enhancement on delayed phase DCE suggests cervical stroma invasion (Fig. 14.4) [9, 27, 28].

Stage III: Tumor invades the uterine serosa or ovaries (Fig. 14.6). A concomitant primary ovarian tumor may be interpreted as a local-regional spread of EC. A primary tumor is suspected when a complex solid-cystic mass with enhancement and restricted diffusion is noted. Stage IIIB includes vaginal or parametrial involvement and IIIC indicates the presence of pelvic and/or para-aortic LN metastases.

Endometrial serous carcinoma: FIGO IIIA. A 78-year-old patient with vaginal bleeding. On T2WI there is a polypoid mass within the endometrial cavity (a, b) with restricted diffusion on DWI (c). Note the adjacent leiomyoma (*) with characteristic low-T2WI SI. The left ovary has intermediate-T2WI SI associated with high-DWI SI (C, arrow); the appearance is suspicious for the involvement of the left ovary. The gross examination of the surgery specimen (d) shows the endometrial tumor (arrowheads), the leiomyoma (*) and the left adnexa (arrow). The pathology revealed endometrial serous carcinoma (e) with spread to the left ovary (f), corresponding to Stage IIIA disease. These images were originally published in Pintican R, Bura V, Zerunian M, Smith J, Addley H, Freeman S, Caruso D, Laghi A, Sala E, Jimenez-Linan M. MRI of the endometrium - from normal appearances to rare pathology. Br J Radiol. 2021 Sep 1; 94 (1125): 20201347. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20201347. Epub 2021 Jul 8. PMID: 34233457; PMCID: PMC9327760

Stage IV: In stage IVA disease tumor invades the bladder or rectal mucosa. A common pitfall is bullous edema of the bladder caused by tumor invasion of the subserosal or muscular layer. In stage IVB distant metastases are present, including lymphadenopathy above renal hilum or inguinal region, malignant ascites, peritoneal deposits, or distant organ metastasis (e.g., lung, liver). CT and/or PET/CT are useful to detect LN and distant metastatic disease.

14.2.7 Evaluation of EC Recurrence

Recurrent endometrial cancer has a similar imaging appearance to the primary tumor. Risk factors for recurrence include advanced stage at presentation, high-grade disease, Type II tumor, and lymphovascular invasion. More than 80% of recurrences occur within 3 years of initial treatment with the vaginal vault (42%) and LNs (46%) as the most common sites. Recurrence in the peritoneum is uncommon but when present suggests Type II EC. MRI is useful for the evaluation of surgical resectability and for surgical planning by confirming that a disease is confined to the pelvis. PET/CT is helpful to exclude the presence of LN and distant metastases [21].

14.3 Concluding Remarks

Imaging evaluation of patients with CC and EC, particularly with MRI and FDG-PET, facilitates optimal treatment selection including confirming eligibility for conservative fertility-sparing management. Imaging is also central to the evaluation of treatment responses, detection of recurrent disease, and optimal selection of potential salvage treatment options.

Take Home Messages

-

MRI excels at loco-regional staging of CC and EC.

-

PET improves N and M staging in uterine malignancies.

-

MRI facilitates patient selection for fertility-sparing management.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Stelzle D, Tanaka LF, Lee KK, Ibrahim Khalil A, Baussano I, Shah ASV, McAllister DA, Gottlieb SL, Klug SJ, Winkler AS, et al. Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e161–9.

Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–8.

Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N. Cervical cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_4):iv72–83.

Bhatla N, Berek JS, Cuello Fredes M, Denny LA, Grenman S, Karunaratne K, Kehoe ST, Konishi I, Olawaiye AB, Prat J, et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;145(1):129–35.

Bentivegna E, Gouy S, Maulard A, Chargari C, Leary A, Morice P. Oncological outcomes after fertility-sparing surgery for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):e240–53.

NCCN Clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines®). Cervical Cancer. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf.

Manganaro L, Lakhman Y, Bharwani N, Gui B, Gigli S, Vinci V, Rizzo S, Kido A, Cunha TM, Sala E, et al. Staging, recurrence and follow-up of uterine cervical cancer using MRI: updated guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology after revised FIGO staging 2018. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(10):7802–16.

Sala E, Rockall AG, Freeman SJ, Mitchell DG, Reinhold C. The added role of MR imaging in treatment stratification of patients with gynecologic malignancies: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiology. 2013;266(3):717–40.

Park JJ, Kim CK, Park SY, Park BK. Parametrial invasion in cervical cancer: fused T2-weighted imaging and high-b-value diffusion-weighted imaging with background body signal suppression at 3 T. Radiology. 2015;274(3):734–41.

Woo S, Atun R, Ward ZJ, Scott AM, Hricak H, Vargas HA. Diagnostic performance of conventional and advanced imaging modalities for assessing newly diagnosed cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(10):5560–77.

Xiao M, Yan B, Li Y, Lu J, Qiang J. Diagnostic performance of MR imaging in evaluating prognostic factors in patients with cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(3):1405–18.

Choi HJ, Ju W, Myung SK, Kim Y. Diagnostic performance of computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/computer tomography for detection of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer: meta-analysis. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(6):1471–9.

Adam JA, van Diepen PR, Mom CH, Stoker J, van Eck-Smit BLF, Bipat S. [(18)F]FDG-PET or PET/CT in the evaluation of pelvic and Para-aortic lymph nodes in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159(2):588–96.

Rockall AG, Ghosh S, Alexander-Sefre F, Babar S, Younis MT, Naz S, Jacobs IJ, Reznek RH. Can MRI rule out bladder and rectal invasion in cervical cancer to help select patients for limited EUA? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101(2):244–9.

Gee MS, Atri M, Bandos AI, Mannel RS, Gold MA, Lee SI. Identification of distant metastatic disease in uterine cervical and endometrial cancers with FDG PET/CT: analysis from the ACRIN 6671/GOG 0233 multicenter trial. Radiology. 2018;287(1):176–84.

Pötter R, Tanderup K, Schmid MP, Jürgenliemk-Schulz I, Haie-Meder C, Fokdal LU, Sturdza AE, Hoskin P, Mahantshetty U, Segedin B, et al. MRI-guided adaptive brachytherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer (EMBRACE-I): a multicentre prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):538–47.

Meyer HJ, Wienke A, Surov A. Pre-treatment apparent diffusion coefficient does not predict therapy response to Radiochemotherapy in cervical Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anticancer Res. 2021;41(3):1163–70.

Harry VN, Persad S, Bassaw B, Parkin D. Diffusion-weighted MRI to detect early response to chemoradiation in cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2021;38:100883.

Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Association of posttherapy positron emission tomography with tumor response and survival in cervical carcinoma. JAMA. 2007;298(19):2289–95.

Lakhman Y, Nougaret S, Micco M, Scelzo C, Vargas HA, Sosa RE, Sutton EJ, Chi DS, Hricak H, Sala E. Role of MR imaging and FDG PET/CT in selection and follow-up of patients treated with pelvic exenteration for gynecologic malignancies. Radiographics. 2015;35(4):1295–313.

Cancer Research UK. Uterine cancer incidence statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/uterine-cancer/incidence#heading-Three. Accessed 17 Sept 2022.

Lee NK, Cheung MK, Shin JY, Husain A, Teng NN, Berek JS, Kapp DS, Osann K, Chan JK. Prognostic factors for uterine cancer in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(3):655–62.

Timmermans A, Opmeer BC, Khan KS, Bachmann LM, Epstein E, Clark TJ, Gupta JK, Bakour SH, van den Bosch T, van Doorn HC, et al. Endometrial thickness measurement for detecting endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):160–7.

Lynch HT, Snyder CL, Shaw TG, Heinen CD, Hitchins MP. Milestones of Lynch syndrome: 1895-2015. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(3):181–94.

Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, Benz CC, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73.

Nougaret S, Horta M, Sala E, Lakhman Y, Thomassin-Naggara I, Kido A, Masselli G, Bharwani N, Sadowski E, Ertmer A, et al. Endometrial Cancer MRI staging: updated guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(2):792–805.

Otero-García MM, Mesa-Álvarez A, Nikolic O, Blanco-Lobato P, Basta-Nikolic M, de Llano-Ortega RM, Paredes-Velázquez L, Nikolic N, Szewczyk-Bieda M. Role of MRI in staging and follow-up of endometrial and cervical cancer: pitfalls and mimickers. Insights Imaging. 2019;10(1):19.

Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, Bosse T, Gonzalez-Martin A, Ledermann J, Marth C, Nout R, Querleu D, Mirza MR, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO consensus conference on endometrial cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(1):2–30.

Creasman W. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105(2):109.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lakhman, Y., Sala, E. (2023). Malignant Diseases of the Uterus. In: Hodler, J., Kubik-Huch, R.A., Roos, J.E., von Schulthess, G.K. (eds) Diseases of the Abdomen and Pelvis 2023-2026. IDKD Springer Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27355-1_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27355-1_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-27354-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-27355-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)