Abstract

This chapter is designed to guide academics and students who wish to undertake research using the cultures framework. It offers a structured approach to cultural research that can be used by researchers from diverse disciplinary backgrounds. The variables and dynamics depicted by the framework are able to be discovered, described and analysed using a wide variety of qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The framework can also be used as a meta-theoretical framing. It invites interdisciplinary endeavours and multi-method research approaches, and operates well as an integrating framework. Further research on culture and sustainability is needed to build up a better understanding of, amongst other things, universal cultural processes, transforming unsustainable meta-cultures, and the multiple roles that culture can play in sustainability transitions. The chapter concludes with suggesting further potential contributions to sustainability research from each of the nine perspectives of culture described in Chapter 2.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Keywords

- Research

- Culture

- Framework

- Guide

- Sustainability

- Qualitative methodology

- Quantitative methodology

- Multi-method

- Meta-theoretical

- Interdisciplinary

- Integrative

- Cultural theory

Introduction

I cannot think of a single research topic relating to the human/sustainability nexus that does not have a cultural component. From globally influential paradigms and the practices of fossil fuel majors to the operations of small businesses and the daily lives of households, culture is involved. Yet as a research topic, culture is often remaindered—applied as a loose label for a collection of features of social existence that sit unexamined alongside other deeply analysed phenomena. Apart from the fraction of researchers trained in forms of cultural analysis, the slippery, qualitative features of culture can seem too hard to investigate by researchers interested in sustainability issues. The cultures framework addresses this difficulty by offering a structured way to approach cultural research that can be used by researchers from almost any disciplinary background. As described in earlier chapters, the framework has been sufficiently tested to have confidence that it can fruitfully guide research endeavours.

Over the 12 years since the framework was first introduced in the literature, it has been used with a broad range of research approaches. It has been used with qualitative methods, quantitative methods and mixed methods. It has been used to formulate research design, as an analytical frame for the interpretation of existing data sets, and as a conceptual framing for meta-reviews of data. It has been used by individual researchers from a single discipline as well as by interdisciplinary research teams. It has underpinned undergraduate studies, postgraduate dissertations and extensive research programmes. It has been used to design research-based interventions and as an evaluation framework. And as shown in earlier chapters, it has been applied to a wide variety of problems and fields of enquiry.

This chapter is designed to guide academics and students who wish to undertake research using the cultures framework. For most of the chapter, I discuss the use of the framework to explore the interplay between culture and sustainability. By providing a structure for research investigations, the framework can help reveal what cultural ensembles, consisting of what cultural features, have causal relationships with what outcomes, affected by what external influences. It can help determine who are the actors within the culture group under study, and which cultural ensembles are already more sustainable than others. By examining the internal dynamics of culture, we can see how this leads to the sustainability outcomes. By studying cultural ensembles in relation to external influences, we can gain insights into why cultures remain static or evolve. By investigating the scope of agency of cultural actors, we can better understand why it is difficult for them to change, and who comprise more powerful organisations or institutions. And by examining whether a culture is dynamically stable or has the potential to change, we can gain insights into whether transformation is possible. Of course, not all these questions will be relevant to a given study, and the choice of questions will be determined by the particular context of the research and the sustainability issues at stake, but this gives an indication of the types of questions for which the framework can be used.

Towards the end of the chapter, I discuss how the framework can also be used as a meta-theoretical framing. In this sense, it can be used as an overarching structuring device for multidisciplinary, multi-theoretical and multi-method research, as with the examples of the Energy Cultures research programmes discussed in Chapter 7. As covered in Chapter 4, it builds on mature social science and cultural theories, and the framework acts as a structuring device for reaching into these fields of knowledge to examine dynamics and causal mechanisms in greater depth. I finish by discussing how the diverse and currently fragmented cultural theories discussed in Chapter 2 can make a stronger contribution to sustainability research.

Core Concepts

On the assumption that some readers may skip directly to this chapter, I will first recap on some key concepts. First, what culture is not. Culture is not about how people operate as individuals, each with their unique personal history and psychology. It is not about demographics. It is not about features that all humans share as social beings. All of these may interplay with culture, but they are not its defining characteristics. Second, the cultures framework is not just about culture. Cultures do not exist in a vacuum, and the framework draws attention to important variables that shape culture and mediate its implications for sustainability outcomes.

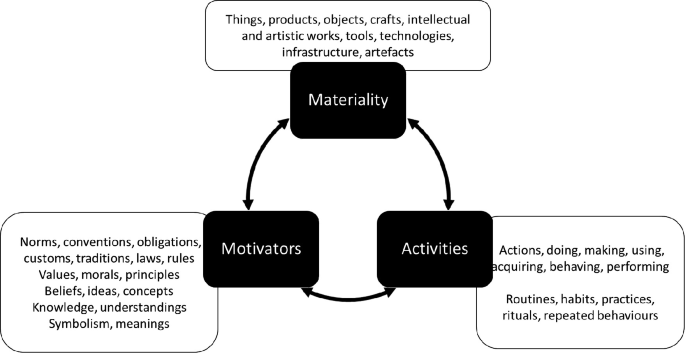

Recapping on what I mean by culture in this context, I describe it in Chapter 4 as comprising distinctive patterns of motivators (norms, values, beliefs, knowledge and symbolism), activities (routines and actions) and materiality (products and acquisitions) that form dynamic ensembles which are shared by a group of people and learned through both cognitive and bodily processes. These cultural ensembles can be most simply described as similar ways of thinking, doing and having that are evident across a group of people. Depending on the focus of research, this could apply to the cultures of people in their everyday lives, or the cultures of organisations or businesses, or cultures at even broader scales of institutions and ideologies.

Rather than focusing on describing groups that we typically think of in cultural terms (e.g. ethnic cultures, youth cultures, American culture), the framework invites inquiries into actors and their cultural ensembles that have implications for sustainability. Relevant actors may be identified at any scale: individuals, households, communities, organisations and beyond. Culture can be investigated in relation to a sustainability problem in both a causal sense and in the way in which cultural dynamics can resist change. Culture can also be investigated as part of sustainability solutions in the sense that many existing cultures are exemplars of sustainability. Cultural change can be a creative and fast-moving force for sustainability transitions.

The range of concerns of sustainability is exemplified by the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015) but as discussed in Chapter 1, the SDGs are only one perspective on sustainability. More critical perspectives suggest that sustainability will not be achieved without more radical change to established systems of production and expectations of consumption. The framework does not predetermine what is meant by sustainability outcomes—this is left to the researcher to determine for their particular context.

The cultures framework has evolved over time. All the research examples I included in previous chapters used earlier terminologies (‘energy cultures framework’ or ‘sustainability cultures framework’) but the core concepts have changed little over time apart from becoming more generic. Earlier versions have produced sound and fruitful findings, and there is no reason why researchers cannot continue to use it in its earlier and slightly simpler form, especially those wishing to take their first forays into this field, in which case the guidance in Stephenson (2018, 2020) will be helpful. In this chapter, I continue to use examples from this prior research, but describe how researchers can undertake inquiries using the revised cultures framework which is presented in Chapter 4. I encourage readers of this chapter to return to Chapter 4 for fuller descriptions of the language, elements and dynamics of the revised framework.

A Guide to Research with the Cultures Framework

The framework can be applied in many different ways to support research processes. One way is to simply use the diagram of the cultural ensemble (Fig. 8.2) as the basis for describing a culture—its distinctive elements and their dynamics. It can be surprisingly difficult to explain what culture is, and these concepts give a solid foundation for identifying cultural features in any given context. At my university, some lecturers ask students to undertake at-home research to describe their own cultural ensembles that relate to energy use or greenhouse gas emissions. The diagram showing the ensemble, agency barrier and external influences (Fig. 8.5) has been used as the basis for discussions about research culture in university departments, and by research organisations to analyse how their own culture may be holding them back from undertaking transformative research. In these instances, it can be a tool for self-reflection, enabling actors to understand and articulate elements of their culture and constraints on change.

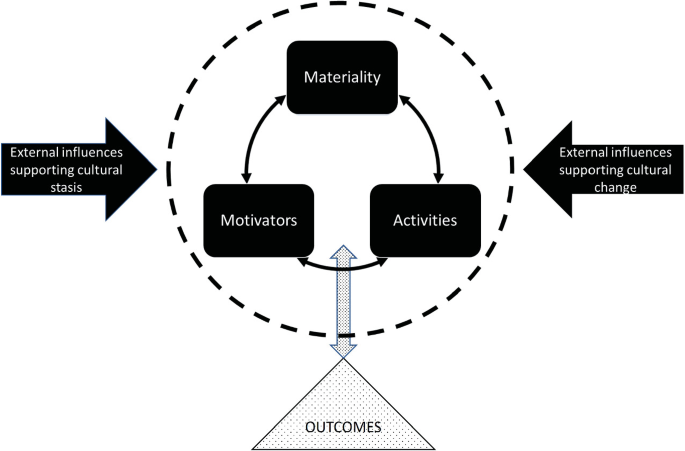

But more commonly, the framework is used by researchers in its full form (Fig. 8.1) for sustainability-related investigations. Some studies primarily seek to describe the cultural characteristics of a particular population. Examples I have discussed in earlier chapters include cooking cultures in Zambia, energy cultures in rural households in Transylvania and mobility cultures in New Zealand. Studies have also used the framework to compare cultures within a population. These have generally sought to explore the contribution of cultural differences to sustainability outcomes. Examples discussed in previous chapters include identifying varied cultural ensembles across populations in relation to energy consumption, energy efficiency and water consumption. Others have explored aspects of culture as influences on people’s readiness to engage in new collective behaviours, their responses to efficiency retrofits and as a factor in nations’ willingness to decarbonise.

The framework is also useful for exploring barriers to cultural change. Studies discussed in earlier chapters have identified cultural characteristics that help explain resistance to change in the US Navy, failures to achieve desired levels of change in social housing interventions and cultural barriers to change in academic air travel. Chapter 7 discusses at length how the framework can be used as a basis for policy development and to underpin the evaluation of interventions.

The following section describes how to use the revised cultures framework to underpin research. For easier reference, I repeat here (as Fig. 8.1) the complete cultures framework diagram (first appearing as Fig. 4.8 in Chapter 4). The section is ordered as a step-by-step process, although it should be noted that not all research will involve all stages, and some research may proceed in a different order or head in different directions. Following this, I describe the range of research methods that have so far been used with the framework, and its methodological inclusivity in general.

Research on culture is research with people. In exploring what is needed to achieve societal transitions towards sustainability, researchers might wish to learn from groups and organisations that have already grappled with what it takes to live sustainably. They may wish to explore unsustainable cultures that seem unlikely to change. They might seek to work with culture groups or organisations that wish to change but can’t, or with those that are already on change journeys. In any situation, the research process and its outcomes have the potential to destabilise established beliefs, ways of life and social processes. Social research is a serious business and must be undertaken ethically and with the consent of, and ideally in collaboration with, those with whose lives you may disrupt.

Determining the Sustainability Outcomes

The cultures framework theorises that cultural ensembles have a causal relationship with sustainability outcomes, a concept that is conveyed by the two-headed arrow in Fig. 8.1. The starting point for research design could be at either end of the arrow. If the sustainability outcomes to be examined are predetermined (e.g. energy consumption, equity, waste reduction), the research might seek to characterise different cultural ensembles within the population that have a causal relationship with these outcomes. Alternatively, the outcomes may be uncertain at the outset, but will emerge from the study. For example, research on the cultural ensembles of elderly households may reveal multiple sustainability implications such as health outcomes, energy expenditure and carbon emissions.

As discussed earlier, the concept of sustainability outcomes can be as broad or as specific, and as conservative or as radical, as the researcher wishes to make it. To be useful for the purposes of the framework, outcomes ideally are measurable (i.e. empirical evidence is available as to whether that outcome is improving or degrading) or at least able to be qualitatively described and compared. Outcomes can be uni-dimensional (e.g. a measure of water quality) or might consist of multiple interconnected qualities (e.g. health, biodiversity, equity). Outcomes may be of widespread benefit (e.g. reducing greenhouse gas emissions) or directly beneficial to the households themselves (e.g. improved health).

The double-headed arrow between cultural ensembles and outcomes also reminds researchers that if outcomes change, this changed context can become a further external influence. For example, if a farmer introduces practices that result in cleaner rivers and streams, this may create positive reinforcement for further cultural change. The farmer may enjoy being able to catch fish again, or seeing their children swimming, or hear positive feedback from community members, and may be encouraged to do more. Research on this kind of feedback could help identify whether and how positive affirmation from more sustainable outcomes can lead to ongoing cultural transformation.

Determining the Cultural Elements and Their Interactions

At an early point in the research process, it will be necessary to determine both the scope of the cultural ensemble and the scope of the member actors. The cultural elements to be studied will ultimately be determined by the sustainability outcomes you are interested in and the actors you are focusing on. For example, if you are interested in carbon emissions from a business sector, the obvious cultural actors to focus on would be those businesses, and the elements to study would be the motivators, materiality and activities that have a direct relationship to carbon emissions. However, from identifying this first-order group of actors, it may become clear that other actors also play a role. It may prove more useful to focus on a sub-group within the business such as senior leadership, or shareholders, or alternatively it may prove important to examine cultural factors at broader scales, such as at the sector level, or within suppliers for these businesses. As a researcher, be open to which group/s of actors it might be most useful to focus on. Depending on the research aim, it might be more useful to gain a rich understanding of the cultural ensembles of a small number of actors, or alternatively to investigate a narrow range of cultural features across a much larger population.

You may find it is useful to examine cultures at multiple scales. Cultures are identifiable and discussable from a minute scale, such as the cultural ensemble of a particular actor or organisation, to massive scales, such as the distinctive and enduring features of Western civilisation. You may find it useful to study the ways in which culture can act as structure—a high-level ensemble of beliefs, symbolism, practices and institutions, which shape other cultures that have less power and reach. The framework is relevant to supporting research at any scale and scope.

The next step is to determine which cultural features are most relevant to your study. The core variables of the framework reflect concepts about culture that repeatedly appear in cultural theories (see Chapter 3). Materiality comprises items that are made, acquired, owned, accumulated, held or nurtured by cultural actors. Activities are frequent and infrequent actions undertaken by cultural actors. Motivators are shared aspects of cognition that include norms, values, beliefs, knowledge and meanings (Fig. 8.2). Which specific features comprise the ensemble for the purposes of your research will depend on the sustainability outcomes, the nature of the actors and of course your interests as a researcher.

I have described a cultural ensemble as a generally consistent pattern of materiality, motivators and activities displayed by an actor or group of actors, but all three may not have equal pertinence depending on the issue—for example, beliefs, meanings or understandings may be more relevant in a particular case than activities or materiality, and vice versa. Cultures will rarely be distinguishable by unique sets of cultural elements; there may be a great deal of overlap between the ensembles of culture groups. The ways in which they are differentiated will be determined by the research context.

When doing research with the cultures framework, how deeply to drill into each element will depend on the nature of the study. For example, in relation to ‘motivators’, many studies to date have focused on depicting norms, because this was the terminology of the original cultures framework. Other studies using the framework have explored morals, meanings, values, knowledge and beliefs, which is one of the reasons for replacing ‘norms’ with ‘motivators’ in the revised cultures framework. In terms of activities, some studies have focused on routines while others have been more interested in one-off or occasional actions. Some have centred on one type of material item, while others have been interested in material assemblages. The nature of the topic should shape the focus of the research, and the researcher should hold open the possibility that relevant but unsuspected cultural features may emerge in the course of the research.

Although the research process will likely identify specific cultural features that can be directly causally related to the outcomes (e.g. the presence of particular technologies or practices), it is the cultural ensemble and dynamics between cultural features that make it ‘cultural’. Research should therefore seek to go beyond simply listing cultural features that bear a relationship to the outcomes of interest, to considering how they interact. Motivators, activities and materiality form the interconnected ‘system’ of culture, as indicated by the curved arrows in Fig. 8.2. How people think influences what they acquire and how they act; people’s activities partly determine what they have and how they think; and the things that people have influence what they do and how they think. Exploring these interactions is critical to understanding how culture operates.

When considering the scope of cultural features to study, some may emerge as more significant than others depending on the sustainability outcomes you are interested in. For example, although sustainability research often focuses on routines or habits, it could be that in some instances, irregular or rare actions have the biggest impacts (noting that these can be equally culturally driven, such as the choice of a new house or whether to buy a car). In fields that you are familiar with, you may have a better chance of an ‘educated guess’ about which cultural features to start investigating, but you may be surprised. In research on household energy efficiency, we started by assuming that people’s values would strongly shape how efficient they were, but we found no consistent relationship between values and actions (Mirosa et al., 2011). So keep an open mind and, of course, explore literature in the field beforehand.

There will always be variability in the extent to which actors adopt cultural ensembles. Cultural uniformity is a myth—in reality, actors will have greater or lesser adherences to the ‘signature’ ensemble that is identified in research. This is not a problem, and indeed can provide useful insights into variability and opportunities for change. For example, if you are interested in sustainable transport, you might find that almost all actors own fossil fuelled cars, but some will use more fuel than others. Car owners will all have driving skills, but some may be more efficient drivers than others. All might drive their cars regularly, but some may drive more frequently than others. From a high-level perspective, they all share a similar mobility culture—one that is dependent on cars and fossil fuels—but if you drilled down you could identify variations in that culture. Where you choose to place your inclusion–exclusion delineation around this group, and whether you choose to segment it into sub-groups, will depend on the purpose of your research.

Ultimately, it doesn’t pay to agonise too much about exactly where to draw a line around the actors and cultural ensembles to study. What we’re interested in as researchers is finding patterns that reflect general similarities in cultural features which relate to sustainability outcomes. It is about sense-making through identifying fuzzy patterns of similarity and difference, which is more fruitful than assuming that everyone is identical.

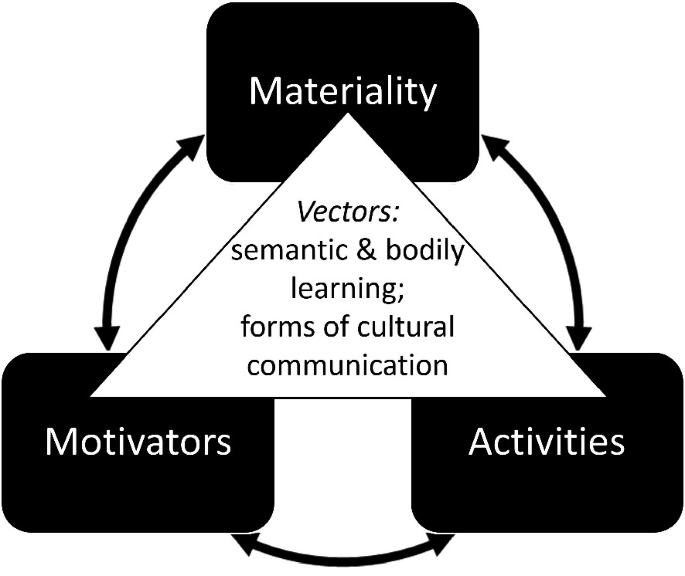

Determining Cultural Vectors

If you are interested in how culture is transmitted, learned and adopted, you may also wish to examine the role of cultural vectors (Fig. 8.3). As discussed in Chapters 4 and 6, vectors include such things as sensory encounters, forms of communication, bodily learning and semantic knowledge that are absorbed from sources such as social interactions, media, bodily experiences and formal learning. Through cultural vectors, people come to adopt similar activities to others, and/or acquire or make similar material items, and/or develop similar norms, aspirations, understandings and other motivators. Vectors are how people learn culture, how it is socially reinforced, and how new cultural concepts are passed from actor to actor.

Cultural vectors will not necessarily be important for all research, but they can help reveal processes of cultural continuity and cultural change. In New Zealand research, for example, we asked householders about alterations they had recently made to improve the heating in their homes, and found that family and friends were by far the biggest influence on their decision. Hearing others' stories of change and experiencing the warmth of others' homes were far more influential than information campaigns, online information or advisory services.

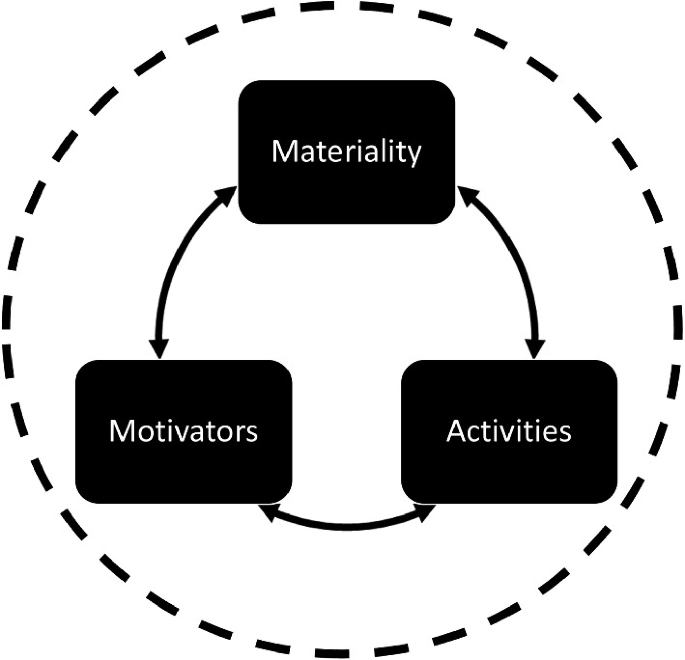

Determining the Agency Boundary

Culture is most often used to describe shared characteristics across a population, but the cultures framework asks researchers to identify a subset of cultural features: those that are both particular to their chosen actors and that could potentially be changed by those actors. This demarcation is indicated in the cultures framework by the agency boundary, shown as a dashed circle around the core elements of culture (Fig. 8.4). The boundary reflects the capacity of the actor to make choices regarding their cultural ensemble. It distinguishes between elements of culture that are particular to and/or controlled by the actor group under study and those that are particular to and/or controlled by others. The actors’ capacity may be constrained by many things, such as their financial circumstances, their age or gender, their education or their familiarity with bureaucratic systems.

In Chapters 4–6, I describe several examples of how this agency distinction is made and used in research. One example is of people on low incomes living within rental housing; the outcomes of interest are energy consumption and wellbeing. Here, the house and chattels owned by the landlord are not considered part of the tenants’ energy culture because tenants have no control over them. The tenants’ cultural ensemble comprises the dynamic package of motivators, activities and materiality that they enact within those constraints. As well as being shaped by the landlord, their energy culture will be shaped by additional influences beyond the agency barrier, such as the cost of power, government policies and other external influences. Another example is personal mobility, where household actors’ cultural ensembles are strongly shaped and constrained by matters beyond their control, such as urban form, the availability of public transport, the safety of walking and cycling and government policies.

The agency boundary in the cultures framework thus invites researchers to differentiate between cultural features that are specific to the group they are studying (within the dashed circle), and other influences that shape (but are rarely influenced by) that culture. It also invites consideration of the factors that are limiting their agency, which may become highly relevant in studies where actors are unable to become more sustainable because of agency constraints. This invites the researcher to consider the implications of differentials in power, the relative responsibility for sustainability outcomes between actors within the agency boundary and those outside it, and their relative ability to act to alter these outcomes. Cultural features beyond actors’ agency belong in ‘external influences’ which may include more powerful cultures.

Determining the External Influences

External influences are exogenous factors that significantly shape the culture that is under study, and are conceptually located outside the agency boundary (Fig. 8.5). As discussed in prior chapters, external influences come in many forms, including qualities of the environment and infrastructure, purposeful policies and laws, pricing regimes, availability of technologies, and broadly accepted beliefs and conventions. For research purposes, it will be important to identify external influences that in some way affect the cultural ensembles under study, and thus ultimately affect the sustainability outcomes. They may, for example, reinforce existing cultural ensembles, erode the integrity of cultures that are already sustainable, force actors to become more unsustainable or support cultural change in a more sustainable direction. Depending on the research focus, some external influences may be apparent from the outset of the study, while others may be obscure and will need to be elicited through deep engagement with cultural actors. External factors that clearly have no influence on the culture under study can be ignored for the purposes of cultural analysis.

External influences can also be interpreted as broader cultures that influence the culture you are focusing on. For example, the mobility cultures of citizens are strongly shaped by cultural features of the municipality. A council that decides to invest its transport funding primarily in new motorways is not doing so arbitrarily. The decision will have emerged from a well-established system of beliefs, understandings, aspirations and organisational practices within the council—in other words, their culture. In researching external influences, it may therefore be important to look beyond their presenting qualities to understand the cultures within which they are embedded and replicated.

Another external influence to consider is your own impact on culture as a result of the research process. By asking questions of research participants, you are likely to be raising their own awareness of aspects of their culture that they may not have considered previously. In your interactions, even if it is not intended, you may make them more aware of the sustainability outcomes of their cultural ensembles, and/or aware of disjunctions between, say, their beliefs and practices, or between their aspirations and material possessions. Your interactions may also cause them to develop new understandings about the sustainability issue of interest, or open their eyes to external influences that they had not previously been aware were shaping their culture. The research process is never neutral, so be aware of how your work may influence your participants’ cultures, ensure that your work is carried out ethically and does no harm, and possibly build an evaluation of your impact as a researcher into your research.

Investigating Cultural Stability

Some cultures change very little over time, or at least in the features that give rise to sustainability outcomes. Some enduring cultural ensembles may be positive examples that research can learn much from, such as communities and organisations that have consciously set out to become more sustainable and have maintained that over time. Other cultural ensembles are deeply problematic from a sustainability perspective, and yet continue to endure. We can see this with highly consumptive lifestyles amongst many in the Western world, with beliefs in the value of consumption for its own sake, aspirations for material items goaded by the media (and today, by social influencers), practices of shopping valued in their own right and made more unsustainable through the proliferation of short-lived products, and wellbeing equated with more (or more wealth-signifying) possessions. The cultures framework offers a structure for exploring how and why many unsustainable cultural ensembles change little over time. It would be helpful to review the examples of research into cultural stability discussed in Chapter 5.

Research into cultural stability might start by examining actors’ cultural ensembles, exploring relevant motivators, material assemblages and activities, and the extent to which these are aligned and mutually supportive. It may investigate cultural vectors in order to understand how cultural attributes are learned, reinforced and conveyed to new members. It would usefully identify what external influences (including structures, institutions and broader-scale cultures) are supporting the culture in its current form and enabling its continuance. It may be useful to look back in time and identify what has shaped the culture you see today. Unpacking these dynamic interactions can help explain how and why this culture is resistant to change.

Understanding these dynamics is particularly important if your research is seeking to understand why change interventions have failed to achieve their targets. Exploring culture as a dynamic system can reveal why change in one external influence or in a single cultural feature (e.g. new knowledge or a new technology) may make little or no difference to sustainability outcomes; for example because its impact is moderated by other cultural dynamics that tend to stabilise the cultural ensemble. Even if some aspects of culture (e.g. values, aspirations) are aligned with sustainable outcomes, other aspects (e.g. routines, agency limitations, external influences) may prevent or limit overall change. It is critical to gain a better understanding of the dynamics of cultural stability if we are to achieve widespread sustainability transitions.

Investigating Cultural Change

The cultures framework can also underpin research on how cultures change. From a sustainability perspective, your investigation might be into positive change, such as new cultural features being adopted with cascading impacts on the entire cultural ensemble. Of particular interest here might be how positive change processes are initiated, and the consequential effects on culture. An example that I described in Chapter 6 was how the replacement of kerosene lamps with solar lights in Vanuatu had a domino effect on many other aspects of culture including everyday practices, gender roles, beliefs, and aspirations for other solar and digital technologies. Your study could equally focus on negative cultural change, seeking to understand how sustainability-oriented cultural characteristics have been lost. For example, in Chapter 6 I described a Māori community where degradation of the inshore fisheries meant that community members could no longer gather traditional foods. The inability to undertake practices resulted in a loss of knowledge and skills that had previously sustained the fishery.

With the cultures framework as a structuring device, a researcher can explore what external influences might be tending to encourage change, as well as what changes are already occurring within that culture and whether these are leading to shifts in other cultural features. In the previous section, I discussed how cultural ensembles could become resistant to change due to strong alignments between motivators, activities and materiality. In contrast, systems where there are misalignments (e.g. aspirations are different to practices; material items don’t fit with beliefs) there is a greater potential for instability, innovation and change. Researchers interested in the potential for change might wish to examine the degree to which the relevant cultural elements are aligned.

Studying the processes of cultural change is critically important to sustainability transformations at all scales. The cultures framework can help to systematise analysis of where cultural change starts, whether it leads to consequential change to the cultural ensemble, the sustainability consequences of this change, and whether incipient changes are prevented by other factors. Cultural change is unlikely to occur all at once—it may involve incremental adjustments to the ensemble over time (e.g. a normative shift may precede a behavioural shift, or a new technology may precipitate new practices). Change also will not be uniform across a culture group, so the analysis may need to include identification of which actors have first made these changes, and through what vectors this has become more widely adopted. More research is needed to better understand the uneven, incremental processes of cultural change as well as the circumstances in which rapid transformation can occur.

People within a culture group rarely get to alter the more powerful external influences shaping their culture. But sometimes it happens, and this is possibly the most powerful driver of transformational change, as discussed towards the end of Chapter 6. This is where cultural changes spread widely across less powerful actors, and membership of the new culture group grows to the extent that it starts to have influence beyond the agency barrier, reshaping the motivators, activities and/or materiality of more powerful actors. If researchers are interested in the potential for radical sustainability transformations, they should focus on the potential for outward as well as inwards flows through the agency barrier. The urgency of the sustainability crisis means that we need to know as much as possible about how to achieve rapid and widespread transformations of dominant unsustainable cultures.

Having an Impact

By now, your research will have produced an understanding of the various elements of the cultures framework and how they interact dynamically, and any external influences that are tending to prevent or enable change. You will understand the limits of actors’ agency, sub-cultures may have been identified and you may have also discovered cultural influences at other scales. You will have gathered evidence as to whether the cultural ensemble has positive or negative outcomes for the relevant measures of sustainability. You will know whether the culture is in the process of change or is resilient to change, and why this may be the case. If the ensemble has poor sustainability outcomes, your findings should indicate whether it has some latent potential for more sustainable change and possible ways in which change could be initiated or supported to achieve more sustainable consequences.

As a researcher, you might want to apply your findings further to actively help in the sustainability transition. Does it show a culture that already has great sustainability outcomes? If so, what can we learn from this and how can this success be supported and amplified? Does the research show a culture that is stuck in unsustainable patterns and unable to change? If so, where are the opportunities to support change? Does it show a culture that is gradually becoming more sustainable but has a way to go? If so, how can that journey be supported? Does is show a culture where attempts have been made towards greater sustainability but those attempts have been unsuccessful? If so, how can your findings help show why this might be the case?

As with many of the research projects using the cultures framework, you could develop recommendations for policy or practical actions. You might build on your work and develop a programme of action research that enables your insights to be trialled. You might assist an organisation or group of actors to interrogate their own culture and begin a process of change. You could collaborate with an already sustainable community over how to challenge the forces that are depleting it, or how to use cultural vectors to extend its reach. There are endless possibilities for making cultural research into a force for positive change.

Research Methodologies

Research with the cultures framework can be undertaken using a broad sweep of qualitative and quantitative methodologies. In this section, I outline the range of research methods that have been successfully used to date that I am aware of, and what functions these methods have played. This section is heavily referenced so that readers can go to the original papers for more detail on the specific methods of data elicitation and analysis.

Most studies to date using the cultures framework have used qualitative methods to examine cultural ensembles, either on their own or in combination with quantitative methods. Solely qualitative research often involves interviews followed by analysis to draw out evidence illustrating cultural elements (e.g. Bach et al., 2020; Lazowski et al., 2018; McKague et al., 2016; Scott & Lawson, 2018; Tesfamichael et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2014). Some projects have used a combination of qualitative methods such as workshops or focus groups together with interviews (e.g. Ambrosio-Albalá et al., 2019; Godbolt, 2015; Krietemeyer et al., 2021). A study of cultural change over an extensive period of time incorporated reviews of archaeological and historical evidence together with present-day interviews (Stovall, 2021). Researchers often apply thematic analyses to their qualitative material, but other analytical methods can be used. For example, a study on energy cultures of poverty analysed the interview texts using a computational social science methodology (Debnath et al., 2021).

Other researchers have used quantitative methods to characterise cultural ensembles. The elements of the framework have underpinned the design of surveys to elicit data from a larger population than is possible with face-to-face qualitative methods (e.g. Lawson & Williams, 2012) and as the basis of an ‘energy culture’ survey for businesses to determine the maturity of their energy efficiency efforts (Oksman et al., 2021). As well as using data produced from surveys specifically designed for this purpose, the cultures framework has been used retrospectively to underpin analysis of existing data sets to identify clusters of similar cultural characteristics aligned with different sustainability outcomes (e.g. Bardazzi & Pazienza, 2017, 2018, 2020; Walton et al., 2020). It has also been used as an integrating framework across multiple quantitative data sets (e.g. Manouseli et al., 2018). There will always be variations in the cultural ensembles of any group of actors, and sometimes it will be useful to explore this variability. Larger quantitative data sets have been used as a basis for segmenting populations into statistically distinctive groups using cluster analysis (e.g. Barton et al., 2013; Lawson & Williams, 2012).

In studies using mixed qualitative and quantitative methods, the cultures framework has underpinned both design and/or analysis, and has been used to facilitate the integration of findings (e.g. Bell et al., 2014; Muza & Thomas, 2022; Scott et al., 2016). Some studies have gathered both qualitative and quantitative data relating to cultural elements during face-to-face interviews and integrate these in the analysis (e.g. Khan et al., 2021). Research on indicators of national energy cultures used a combination of policy analysis and quantitative analysis of comparative data sets (Stephenson et al., 2021).

To explore external influences (including multi-level cultures), studies often ask interviewees within the culture group about their perceptions of what shapes their decision-making or constrains their ability to make more sustainable choices (e.g. Ambrosio-Albalá et al., 2019; Debnath et al., 2021; McKague et al., 2016). Some also seek the views of experts or key informants in particular fields (e.g. Stephenson et al., 2015) or review the impact of laws and policies (e.g. Barton et al., 2013). Some projects have also interviewed actors who represent aspects of external influences (e.g. Jürisoo et al., 2019; Nicholas, 2021).

Many different research approaches can be used to identify causal relationships between cultural ensembles and sustainability outcomes. Some studies have done this quantitatively, such as identifying relationships between householder age cohorts and energy consumption (Bardazzi & Pazienza, 2017) and between timber drying cultures and energy use (Bell et al., 2014). One study used regression analysis to relate householders' cultural features to their interest in being involved in a local energy management scheme (Krietemeyer et al., 2021). However, in most studies to date using the cultures framework causal relationships are not quantified but are assumed based on well-established understandings of sustainable practices or the impacts of different technologies (e.g. Dew et al., 2017; Hopkins, 2017). Often the focus of research has been on whether the cultural ensemble has features that are known to align with more sustainable outcomes (e.g. types of technology and practices that represent business energy efficiency [Oksman et al., 2021; Walton et al., 2020]) rather than setting out to prove the well-understood relationship between these and measurable outcomes.

The framework has also assisted with modelling. A design for agent-based modelling for smart grid development drew from the cultures framework to incorporate energy use behaviours into the models (Snape et al., 2011). A project using system dynamics modelling of the uptake of electric vehicles also used the elements of the cultures framework as foundational data for the model (Rees, 2015). Methods such as these align well with the original conceptual framing of culture as a system, and offer a dynamic structure to explore system-type interactions between components of the framework.

The framework lends itself to multi-scalar analysis, as with research on PV uptake in Switzerland, where the work described generalised cultural ensembles of adopters and non-adopters and also drew insights on cultural processes from individuals (Bach et al., 2020). By focusing on collectives, researchers can observe patterns of similar cultural features across a population and identify broadly similar influences on and outcomes of that culture. By focusing on individual actors, they can also explore in detail the dynamics within cultural ensembles.

The framework has also been used to structure reviews of literature. Examples include reviews of the adoption of energy-efficient technology innovations in buildings (Soorige et al., 2022), academic air travel cultures (Tseng et al., 2022) and adoption of natural gas (Binney & Grigg, 2020). In a study on barriers and drivers for industrial energy efficiency, the framework was refined to fit an industrial context and used as an organising framework for metadata from a literature review on the barriers and drivers of energy behaviour in firms. This approach enabled the researchers to consider many interdependent components of efficiency decision-making by industry, including attitudinal factors, behaviours and technologies (Rotzek et al., 2018).

Some studies have investigated the effectiveness of interventions intended to improve sustainability outcomes. In these instances, they have used the framework to guide collection of pre-intervention and post-intervention data on cultural ensembles and/or outcomes (e.g. Rau et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2016). Other work has used the framework to design evaluation tools (e.g. Ford et al., 2016; Karlin et al., 2015).

Within larger research programmes, the framework can be used as a structuring device for allocating research roles and methods across an interdisciplinary team. In the Energy Cultures 1 and 2 research programmes, for example, we identified the core elements of culture in relation to energy efficiency (material aspects, practices, norms, beliefs, etc.) through householder questionnaires, focus groups and interviews. To relate cultural ensembles to energy outcomes, we included questions about energy consumption in the surveys and in later work we used data from smart electricity meters. Interrelationships between elements of the framework were explored in various ways. We used a values ‘laddering’ approach (from consumer psychology) to look at the relationships between values and household energy efficiency actions (Mirosa et al., 2013) and used choice modelling (an economics tool) to examine the interactivity between people’s motivators and preferences for adoption of efficient technologies (Thorsnes et al., 2017). These were staged so that the values work helped in the design of the choice modelling. We explored interactions between norms, material culture and practices with community focus groups, and these groups also assisted in identifying external influence that were barriers to changing behaviour. Desktop studies were used to examine regulatory, market and policy influences on energy culture. We used social network analysis to identify the most common sources of external influence on householder choices to adopt more efficient technologies. All of these different sources of insight were linked though the framework, which supported an integrative approach across the team, learning from each other’s findings and contributing to a holistic understanding of household energy cultures in the New Zealand context (Barton et al., 2013; Stephenson et al., 2010).

The framework is thus helpful in underpinning the design of research as a single- or multi-method project by an individual researcher, or a multi-method multidisciplinary research programme by a team. It can be used proactively to design research and analyse the findings, or used retrospectively to help analyse existing data from single or multiple sources. It is fruitful when used as a theory in its own right, and also when used in combination with other theories.

Using the Cultures Framework as a Meta-Theoretical Framing

As these examples have shown, research using the cultures framework is not confined to particular methods, and neither is it confined to any particular theoretical or disciplinary perspective. In this sense, the framework offers a meta-theoretical set of universal elements, and leaves it to the researcher to determine which theories and methodologies are best used to examine them. Rau et al. (2020) describe the advantages of the framework thus:

The benefits of using the [cultures framework] to organise the empirical material and findings of this interdisciplinary energy research were considerable, especially given its focus on the multi-method investigation of a small number of households. Its relative simplicity, easy-to-understand terminology and focus on both social and material aspects of energy use made it an ideal tool for fusing insights from the social sciences, engineering and architecture. At the same time, [the framework] was capable of connecting a higher-order theoretical approach (energy cultures) to concrete empirical energy-related outcomes. (p. 10)

While many studies use the cultures framework as a framing theory in its own right, it is at the same time an organising framework that enables multiple methods, theories and disciplines to contribute to an understanding of culture in relation to sustainability. Studies using the cultures framework to date have drawn from complementary explanatory theories as diverse as sociological theories of agency, structure, institutions and practice, theories of power and gender, behavioural theories, socio-technical systems theories, consumer psychology, economic theories, the multi-level perspective and, of course, theories of culture. Generally, these are used to inform analysis of an aspect of the cultures framework.

This flexibility is well explained by Ambrosio-Albalá et al. (2019) in their conclusion to a paper on public perceptions on distributed energy storage in the United Kingdom:

… we find that the framework functions as a useful heuristic, allowing us to organise and reflect on a wide range of factors in a way that is more inclusive than a psychology-only perspective. The idea of there being multiple possible cultures in relation to energy use – and the observation of these at different scales – also helps to stimulate thinking on further research directions in terms of how different households, demographic segments, nationalities and entities may differ in terms of the nexus of norms, attitudes, behaviours or practices and material experiences. These cultures will likely need different types of communication, informational, institutional and contractual offers, given likely differing responses. A further value of the ECF [energy cultures framework] – regarding which we would concur with its originators – lies in its comprehensibility for non-social scientists. For more specialised and narrowly specified forms of analysis, we would defer to the psychological and sociological perspectives that the ECF draws upon. (p. 149)

There are many under-explored possibilities for the use of other theories and bodies of knowledge to help explore aspects of culture in relation to sustainability. For example, in relation to the theory of structuration, culture works both to replicate social life and as a creative force for change. The framework positions culture as constrained and shaped by structure, while simultaneously situating more powerful cultures as part of structure. Despite these constraints on their agency, cultural actors can and do make independent choices and can collectively reshape more powerful structures and cultures. This interplay (and the conceptual overlap of culture and structure) invites further exploration in both a theoretical and applied sense, particularly in the context of the implications for sustainability transitions.

Conceptual fields that underpinned the development of the cultures framework could be drawn from more extensively, including lifestyles literatures, socio-technical studies, actor network theory, systems approaches, and sociological and anthropological theories of culture. For example, social practice theory can help illuminate aspects of the inner elements of the framework, with a focus on habitual actions. Theories of power and justice can help elaborate on the reasons for limitations in agency and choice that are imposed by those outside the agency boundary. Socio-technical systems theories can assist in exploring the relationships between actors’ material items and their activities. Theories of gender can help explores difference in cultural meaning, gender equity and gender leadership in sustainability outcomes. In all of these ways and more, the framework can offer a meta-theoretical structure for deeper analysis depending on the inclinations and interests of the researcher.

Further Contributions From Cultural Theory

A further untapped potential lies in the application of cultural theories more generally to questions of sustainability. Cultural theory is a vast field that I could only sketch out lightly in Chapters 2 and 3. There I discussed divergences and similarities across cultural theories and identified nine main clusters of perspectives on culture. I believe that each of these perspectives on culture can make an important contribution to research for a more sustainable future.

Culture-as-nature is the oldest of the nine perspectives. It is mostly overlooked by dominant ideologies, and yet its endurance offers the most hope. Culture-as-nature reflects many Indigenous perspectives that defy the intellectual separation of human society and natural systems. Culture-as-nature recognises our utter dependence on the natural world. The most powerful expressions of culture-as-nature continue to come from Indigenous peoples, although recent years have seen an increasingly strong voice from Western scholars (e.g. Haraway, 2016; Plumwood, 2005; Tsing et al., 2017). Culture-as-nature reinforces the indivisibility of human existence from nature and the responsibilities of human societies to maintain the integrity of natural systems. It also breaks down the barriers of cultural membership. Natural features are actors in culture: mountains and creatures are family members, trees communicate, rivers are people; they are all cultural members with agency. Many of the Indigenous societies of the world offer principles, values, practices, knowledges and worldviews that are crucial for a sustainable future (Artelle et al., 2018; Mazzocchi, 2020; Watene & Yap, 2015; Waldmüller et al., 2022; Yunkaporta, 2020).

Culture-as-nurture reflects the original meaning of culture in old English, referring to processes of husbandry—the careful tending of crops and animals. For the sustainability crisis, we are relearning the urgency of nurturing all life forms and regenerating natural systems. As well as reinforcing the importance of healthy natural systems and food production, culture-as-nurture can be further interpreted as the re-grounding of communities in caring for place, and reviving the spiritual roots of agriculture (Bisht & Rana, 2020; van den Berg et al., 2018). Urban agriculture or community gardens similarly reconnect people to the practices and rhythms of caring for nature, along with the sharing of food and strengthening a sense of community (Sumner et al., 2011). Culture-as-nurture reflects the ways in which we must re-learn practices of caring for nature, and how caring for nature aligns with caring for each other.

The original sense of culture-as-progress was the process of human development towards a so-called civilised state that reflected certain Western ideals of art and behaviours. Although it is now repellent and largely obsolete in this original sense, the idea of ‘progress’ can be reconfigured to refer to cultural journeys towards sustainability. Culture-as-progress in this sense can recognise the many cultural configurations that already have sustainable outcomes. It invites investigations of factors that underpin the relative sustainability of one culture compared to another (Buenstorf & Cordes, 2008; Minton et al., 2018) and the application of cultural evolution concepts to sustainability challenges (Brooks et al., 2018). A practical application of this in the world of business is the concept of energy culture ‘maturity’ and evaluation methods to assess such progress (Soorige et al., 2022). If the concept of progress is applied to outcomes rather than to cultural characteristics in themselves, this removes the suggestion that certain forms of cultural ensemble are better than others. Instead, a sustainable future requires a multitude of sustainable cultural ensembles specific to people and place, at a multitude of scales.

Culture is still commonly used to refer to works and practices of artistic and intellectual activity. In this sense, culture-as-product plays an important role as a cultural vector in transmitting ideas, values and possibilities. For the sustainability transition, creative works will play a critical role in challenging systems, institutions and practices that are destroying natural systems and demeaning humanity, as well as offering inspiration for alternate futures. Cultural products have the potential to convey different understandings, such as about the world’s ecological limits, actions for sustainability and new perspectives of the future (Curtis et al., 2014). This is already a strong theme in art and performance (Galafassi et al., 2018; Kagan, 2019) but could play an even stronger role in helping shape awareness and collective visioning for a sustainable future.

Culture-as-lifeways draws originally from anthropological studies of the distinctive way of life of a group of people. From a sustainability perspective, this concept can be redirected from studying the ways of life as a focus in their own right, to looking at the relationship between ways of life and the sustainability outcomes. From a research perspective, it encourages work that explores the variety of ways that people already live sustainably—for example, differences between ways of life in the global north and global south (Hayward & Roy, 2019), as well as how group or community ways of life can be re-oriented towards more sustainable consequences (Brightman & Lewis, 2017).

Culture-as-meaning focuses on the shared meanings and symbolisms of cultural objects such as text, discourse and possessions. For the sustainability challenge, culture-as-meaning can help reveal the ways in which symbolism can work for or against sustainable outcomes. Theories of cultural meaning could be applied to the analysis of how unsustainability is inherent in dominant rhetoric, text and discourse (e.g. Sturgeon, 2009), and the ways in which new meanings are being forged as part of cultural transformations (e.g. Hammond, 2019). Other examples of work using culture-as-meaning include a study of how the term ‘sustainable development’ is constructed in the disclosures of Finnish-listed companies (Laine, 2005), how the media interprets sustainability (Fischer et al., 2017) and the importance of symbolism in marketing for the sustainability transition (Kumar et al., 2012; Sheth & Parvatiyar, 2021).

Culture-as-structure is interested in the underlying rules by which social systems are reproduced—the cultural codes of social life. Culture-as-structure, as embedded in institutions and discourses, is intimately tied with questions of power and influence regardless of intent (Blythe et al., 2018). Drawing on this literature can help identify and challenge ideologies, assumptions and rules that replicate unsustainability. Relevant studies using culture-as-structure include how neoliberal ideology operates through sustainability discourses (Jacobsson, 2019) and the mental structures in which finance actors are embedded (Lagoarde-Segot & Paranque, 2018).

Culture-as-practice studies the bodily practices that produce and replicate social life, and the intimate linkages between routines, objects, meanings and competencies. This field of work can contribute to questions of how to alter practices, or develop new practices that support sustainability. Practice theory has already been widely applied to how to achieve less resource-intensive habits and routines, including how the reproduction of social practice can sustain inequality and injustice (Shove & Spurling, 2013) and to provide insights on collective action for social change (Welch & Yates, 2018).

Culture-as-purpose reflects bodies of work that focus on how to change the culture of organisations or groups of actors intentionally. Work in the field of organisational culture includes how to deliberately create more sustainable organisations (Galpin et al., 2015; Obal et al., 2020). Education for sustainability is another major field working on purposeful culture change, building on and extending educational theories (Huckle & Sterling, 1996) and education’s transformative potential (Filho et al., 2018). This includes using practices of dance and music to develop pro-social behaviours that align with sustainability goals (Bojner et al., 2022).

All nine conceptualisations of culture thus make important contributions to understanding the role of culture in sustainability. It is evident that at least some academics in each of these fields are applying relevant theories and methodologies to sustainability questions, but it appears to be occurring in a fragmented way with different bodies of knowledge scarcely acknowledging each other. Even if there is a ramping up of scholarly contributions on culture and sustainability, there is the risk that the slipperiness of culture as a concept will continue to handicap the use of research findings by practitioners and policymakers. If culture continues to be presented as if each part of the elephant is the full elephant, and the only true elephant, its ongoing indeterminacy will continue to confuse potential research users and dilute the effectiveness of scholarly contributions.

The cultures framework could help here by ‘locating’ these different approaches to culture and their contribution to sustainability challenges. Each of the nine clusters of meaning can offer insights for certain features or qualities of the framework. Using its meta framing, culture-as-purpose focuses on how to purposefully initiate cultural change and achieve better sustainability outcomes. Culture-as-practice focuses on routines as a subset of activities, emphasising how they cannot be understood in isolation from the objects, competencies and meanings associated with them. Culture-as-structure helps explore entrenched external influences or higher-order cultures that use their power to shape the cultural ensembles of less powerful actors. Culture-as-meaning focuses on the meanings and symbolism of activities and objects and can help illuminate the mechanisms of cultural vectors.

Culture-as-lifeways scholarship can help in studying how culture is learned, the dynamics of the core elements of culture, processes of replication or change, and the heterogeneity of cultural ensembles. In the arts, culture-as-product scholarship can help enhance the role of creative activities and products in building a more sustainable future. Academic fields that align with culture-as-progress focus more on the two-ended arrow that links cultural ensembles and outcomes and can help with studies on the many journeys involved in achieving cultures that touch lightly on the earth.

Culture-as-nurture scholarship contributes to the adoption of more nurturing food-production activities that also enhance social and environmental outcomes. Culture-as-nature opens the door to entirely different worldviews and knowledge systems regarding humans’ relationships with the natural world. Importantly, it extends cultural actors to include non-human life forms, spiritual beings and landscape features. In this way, it offers ways of understanding the sustainability transition as a process of restoring health and vitality to all living things and the natural systems that support them.

The cultures framework can thus work as an integrative heuristic, indicating how different interpretations of culture all contribute in important ways to a fuller understanding of the role of culture in sustainability. Used in this way, the framework can help reveal the complementary roles of these diverse approaches to practitioners and non-cultural academics. It can also indicate to researchers where it might be useful to reach back to the original bodies of cultural theory and bodies of knowledge to help illuminate particular aspects of the overall ‘elephant of culture’. In this way, cultural scholarship can be used more comprehensively and systematically to support sustainability transitions, and the slipperiness of culture is somewhat reduced.

Conclusion

As this chapter has demonstrated, there is no ‘right way’ to do research with the cultures framework. It is a set of highly generalised variables and their relationships, which can be explored using a wide range of research methods and theories. Researchers can choose which features within the general variables to focus on and can apply the framework at any scale and to any set of actors. The framework can be used as a framing theory in its own right, or alternatively (or simultaneously) can operate as an integrating frame for interdisciplinary, multi-method research, or as a meta-theoretical framing of the complex field of culture and sustainability. Either on its own or in combination with other frameworks and theories, the cultures framework thus offers ontological and epistemological inclusiveness for transdisciplinary research agendas.

There is an urgent need for a better understanding of the role of culture in the sustainability crisis and how to transform the unsustainable cultures that are inherent in most systems of production and consumption. Technologies alone will not achieve a net-zero world by 2050, or turn around our devastating losses of biodiversity, or enable equitable access to energy for families in developing countries. It will take more than simply changes in behaviour. It will require fundamental changes in the motivators, activities and materialities of people and organisations at every scale. We can learn much from cultures that are already sustainable or are on journeys of transition, but the biggest challenge is how to achieve transformational cultural change, at scale, and with unprecedented speed. To that end, research is desperately needed to improve our understanding of processes of cultural change, and particularly to understand how powerful meta-cultures can be destabilised and their unsustainable ideologies and institutions transformed.

Although the framework has already been used in a wide variety of fields, it has the potential to do much more to assist with journeys of transition. We need to know more about how sustainable cultures develop and endure, a better understanding of the dynamics of cultural change and the role of vectors in cultural learning, as well as processes of cultural expansion and collectivisation. More research is needed on the implications of actors having multiple cultural ensembles in different aspects of their life (e.g. the interplay between their food culture, mobility culture and household energy culture). Researchers could fruitfully explore how these overlapping cultures influence and shape each other, or divergences between cultural settings at home and at work. We need to better understand how cultural transformations can be enabled, and the roles that culture will need to play to achieve sustainability transitions. And while some research using the framework has explored issues of power and justice, there is much more to be done.

Cultural research can work at two levels in this quest for transformation. On the one hand, cultures are unique as to membership and cultural features. Researchers can draw conclusions regarding specific cultural ensembles and their sustainability outcomes, and can make recommendations for change initiatives. However, these will usually only be relevant to the case in question. On the other hand, as more studies are undertaken, we can start to build up generalisable understandings of cultural dynamics as they relate to sustainability. Across multiple studies, the research community can develop a better picture of universal cultural processes and effective change interventions.

Finally, although this chapter is about culture and sustainability, the research approach I describe in this chapter could be used in other fields of inquiry. It was developed for sustainability-related research and has mainly been used for that purpose, but it could equally be applied to investigations of culture for any other reason, and in relation to any other outcome. But my hope is that it will continue to be primarily used for research that helps achieve a just transition to a sustainable future.

References

Ambrosio-Albalá, P., Upham, P., & Bale, C. S. E. (2019). Purely ornamental? Public perceptions of distributed energy storage in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 48, 139–150.

Artelle, K. A., Stephenson, J., Bragg, C., Housty, J. A., Housty, W. G., Kawharu, M., & Turner, N. J. (2018). Values-led management: The guidance of place-based values in environmental relationships of the past, present, and future. Ecology and Society, 23(3).

Bach, L., Hopkins, D., & Stephenson, J. (2020). Solar electricity cultures: Household adoption dynamics and energy policy in Switzerland. Energy Research and Social Science, 63, 101395.

Bardazzi, R., & Pazienza, M. G. (2017). Switch off the light, please! Energy use, aging population and consumption habits. Energy Economics, 65, 161–171.

Bardazzi, R., & Pazienza, M. G. (2018). Ageing and private transport fuel expenditure: Do generations matter? Energy Policy, 117, 396–405.

Bardazzi, R., & Pazienza, M. G. (2020). When I was your age: Generational effects on long-run residential energy consumption in Italy. Energy Research & Social Science, 70, 101611.

Barton, B., Blackwell, S., Carrington, G., Ford, R., Lawson, R., Stephenson, J., Thorsnes, P., & Williams, J. (2013). Energy cultures: Implication for policymakers. Centre for Sustainability, University of Otago.

Bell, M., Carrington, G., Lawson, R., & Stephenson, J. (2014). Socio-technical barriers to the use of energy-efficient timber drying technology in New Zealand. Energy Policy, 67, 747–755.

Binney, M., & Grigg, N. (2020). The energy cultures framework: Understanding material culture barriers to the uptake of natural gas. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 16(5), 105–139.

Bisht, I. S., & Rana, J. C. (2020). Reviving the spiritual roots of agriculture for sustainability in farming and food systems: Lessons learned from peasant farming of Uttarakhand hills in North-western India. American Journal of Food and Nutrition, 8(1), 12–15.

Blythe, J., Silver, J., Evans, L., Armitage, D., Bennett, N. J., Moore, M., Morrison, T. H., & Brown, K. (2018). The dark side of transformation: Latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode, 50(5), 1206–1223.

Bojner Horwitz, E., Korošec, K., & Theorell, T. (2022). Can dance and music make the transition to a sustainable society more feasible? Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 1–15.

Brightman, M., & Lewis, J. (Eds.). (2017). The anthropology of sustainability: Beyond development and progress. Palgrave Macmillan.

Brooks, J. S., Waring, T. M., Borgerhoff Mulder, M., & Richerson, P. J. (2018). Applying cultural evolution to sustainability challenges: An introduction to the special issue. Sustainability Science, 13(1), 1–8.

Buenstorf, G., & Cordes, C. (2008). Can sustainable consumption be learned? A model of cultural evolution. Ecological Economics, 67(4), 646–657.

Curtis, D. J., Reid, N., & Reeve, I. (2014). Towards ecological sustainability: Observations on the role of the arts. SAPIENS: Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society, 7(1), [online].

Debnath, R., Bardhan, R., Darby, S., Mohaddes, K., Sunikka-Blank, M., Coelho, A. C. V., & Isa, A. (2021). Words against injustices: A deep narrative analysis of energy cultures in poverty of Abuja, Mumbai and Rio de Janeiro. Energy Research & Social Science, 72, 101892.

Dew, N., Aten, K., & Ferrer, G. (2017). How many admirals does it take to change a light bulb? Organizational innovation, energy efficiency, and the United States Navy’s battle over LED lighting. Energy Research & Social Science, 27, 57–67.

Filho, W. L., Raath, S., Lazzarini, B., Vargas, V. R., Souza, L. De, Anholon, R., Quelhas, O. L. G., Haddad, R., Klavins, M., & Orlovic, V. L. (2018). The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 199, 286–295.

Fischer, D., Haucke, F., & Sundermann, A. (2017). What does the media mean by ‘sustainability’ or ‘sustainable development’? an empirical analysis of sustainability terminology in german newspapers over two decades. Sustainable Development, 25(6), 610–624.

Ford, R., Karlin, B., & Frantz, C. (2016). Evaluating energy culture: Identifying and validating measures for behaviour-based energy interventions. Proceedings of the International Energy Policies & Programmes Evaluation Conference, 1–12.

Galafassi, D., Kagan, S., Milkoreit, M., Heras, M., Bilodeau, C., Bourke, S. J., Merrie, A., Guerrero, L., Pétursdóttir, G., & Tàbara, J. D. (2018). ‘Raising the temperature’: The arts in a warming planet. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 31(2), 71–79.

Galpin, T., Whittington, J. L., & Bell, G. (2015). Is your sustainability strategy sustainable? Creating a culture of sustainability. Corporate Governance, 15(1), 1–17.

Godbolt, Å. L. (2015). The ethos of energy efficiency: Framing consumer considerations in Norway. Energy Research & Social Science, 8, 24–31.

Hammond, M. (2019). Sustainability as a cultural transformation: The role of deliberative democracy. Environmental Politics, 29(1), 173–192.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Hayward, B., & Roy, J. (2019). Sustainable living: Bridging the north-south divide in lifestyles and consumption debates. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44, 157–175.

Hopkins, D. (2017). Destabilising automobility? The emergent mobilities of generation Y. Ambio, 46(3), 371–383.

Huckle, J., & Sterling, S. R. (Eds.). (1996). Education for sustainability. Earthscan.

Jacobsson, D. (2019). In the name of (Un)sustainability: A critical analysis of how neoliberal ideology operates through discourses about sustainable progress and equality. TripleC, 17(1), 19–37.

Jürisoo, M., Serenje, N., Mwila, F., Lambe, F., & Osborne, M. (2019). Old habits die hard: Using the energy cultures framework to understand drivers of household-level energy transitions in urban Zambia. Energy Research and Social Science, 53, 59–67.

Kagan, S. (2019). Culture and the arts in sustainable development. In T. Meireis & G. Rippl (Eds.), Cultural Sustainability: Perspectives from the humanities and social sciences (pp. 127–139). Routledge.

Karlin, B., Ford, R., & McPherson Frantz, C. (2015). Exploring deep savings: A toolkit for assessing behavior-based energy interventions. International Energy Program Evaluation Conference, 1–12.

Khan, I., Jack, M. W., & Stephenson, J. (2021). Dominant factors for targeted demand side management: An alternate approach for residential demand profiling in developing countries. Sustainable Cities and Society, 67, 102693.

Krietemeyer, B., Dedrick, J., Sabaghian, E., & Rakha, T. (2021). Managing the duck curve: Energy culture and participation in local energy management programs in the United States. Energy Research & Social Science, 102055.

Kumar, V., Rahman, Z., Kazmi, A. A., & Goyal, P. (2012). Evolution of sustainability as marketing strategy: Beginning of new era. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 37, 482–489.

Lagoarde-Segot, T., & Paranque, B. (2018). Finance and sustainability: From ideology to utopia. International Review of Financial Analysis, 55, 80–92.

Laine, M. (2005). Meanings of the term “sustainable development” in Finnish corporate disclosures. Accounting Forum, 29(4), 395–413.

Lawson, R., & Williams, J. (2012). Understanding energy cultures. Annual Conference of the Australia and New Zealand Academy of Marketing (ANZMAC). University of New South Wales, Adelaide.

Lazowski, B., Parker, P., & Rowlands, I. H. (2018). Towards a smart and sustainable residential energy culture: Assessing participant feedback from a long-term smart grid pilot project. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 8(1), 1–21.

Manouseli, D., Anderson, B., & Nagarajan, M. (2018). Domestic water demand during droughts in temperate climates: Synthesising evidence for an integrated framework. Water Resources Management, 32(2), 433–447.

Mazzocchi, F. (2020). A deeper meaning of sustainability: Insights from indigenous knowledge. Anthropocene Review, 7(1), 77–93.

McKague, F., Lawson, R., Scott, M., & Wooliscroft, B. (2016). Understanding the energy consumption choices and coping mechanisms of fuel poor households in New Zealand. New Zealand Sociology, 31(1), 106–126.

Minton, E. A., Spielmann, N., Kahle, L. R., & Kim, C. H. (2018). The subjective norms of sustainable consumption: A cross-cultural exploration. Journal of Business Research, 82(December 2016), 400–408.

Mirosa, M., Gnoth, D., Lawson, R., & Stephenson, J. (2011). Rationalizing energy-related behavior in the home: Insights from a value laddering approach. (June), 2109–2119. European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy Summer Study.

Mirosa, M., Lawson, R., & Gnoth, D. (2013). Linking personal values to energy-efficient behaviors in the home. Environment and Behavior, 45(4), 455–475.

Muza, O., & Thomas, V. M. (2022). Cultural norms to support gender equity in energy development: Grounding the productive use agenda in Rwanda. Energy Research & Social Science, 89(February), 102543.

Nicholas, L. (2021). On common ground: How landlords & tenants shape thermal performance of private rental properties. University of Otago.

Obal, M., Morgan, T., & Joseph, G. (2020). Integrating sustainability into new product development: The role of organizational leadership and culture. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 30(1), 43–57.