Abstract

This study explored the role of information sources in vaccine decision-making among four culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities—Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, and Spanish-speaking in the U.S. Specifically, research questions focused on examining: (a) the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19 and whether it differs across members of the four CALD communities; (b) if they find health information that they trust and if there are differences between the ability to find this health information and their vaccination status; and (c) health information sources COVID-19 vaccinated and intended-to-be vaccinated members of the four CALD communities use on a regular basis and this information use compared across the members of these communities. Analysis of survey responses (N = 318) demonstrated that obtaining trusted health information contributed to COVID-19 vaccination decisions among members of the four CALD communities. Vaccine recipients rely on multiple sources of information to protect themselves and their families against the risk for COVID-19. Healthcare providers and policymakers should target health information sources trusted by CALD communities for COVID-19 vaccine communication to these communities. These information sources can be more effectively leveraged to achieve increased diffusion of vaccine information and greater vaccine uptake.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fact that an individual’s demographic characteristics can shape their health outcomes and predict their likelihood of accessing life-saving vaccines, services, or protection from exposure during a global pandemic has been well documented. The intersection of poverty, medical bias/racism, nativity, and immigration status along with a healthcare system that remains insufficiently responsive to the unique needs of culturally and linguistically diverse communities and the social determinants of their health outcomes have proven deadly for many in these communities (Batalova, 2020; Ross et al., 2020).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, CALD communities in the U.S. had to shoulder a disproportionate burden of infections and fatalities due to (a) overrepresentation in the essential workers’ sector including the healthcare industry; (b) lack of ability to maintain social distancing due to the nature of work and life in crowded quarters and neighborhoods; (c) lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate prevention materials; (d) inequitable access to healthcare services (Borjas, 2020); and (e) barriers to healthcare access and vaccine hesitancy (Abba-Ali et al., 2022). Limited English Proficient (LEP) individuals were 35% more likely than their English-speaking counterparts to die from COVID-19. Black, Latino, and Native American patients were more likely than their White counterparts to report higher hospitalization and death (Bebinger, 2021; Tai et al., 2021).

The miracle of modern medicine has provided a promise of an escape from the darkness of the pandemic. Vaccine rollout, however, has again exposed serious flaws in a system that has not yet integrated the needs of CALD individuals (i.e., those who speak a language other than English and subscribe to different cultural beliefs toward health care and disease prevention and treatment). As of July 2022, only 41 states and Washington D.C. reported vaccination data by race and ethnicity. Across these states, vaccination rates among Asians, Hispanics, and Whites were reported at 87, 67, and 64%, respectively. These groups were vaccinated at a higher rate than their Black counterparts, where only 59% of the total Blacks in these states were vaccinated. Furthermore, the share of Blacks and Latinos who received the first booster dose was lower compared to their white counterparts (Ndugga et al., 2021).

Refusal or delayed acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines can be influenced by certain contextual factors, including historical, cultural, socioeconomic, institutional, political, as well as vaccine safety or personal beliefs (Saied et al., 2021). Past research has shown that information source is an important factor in forming vaccine attitudes. For example, parents search the Internet to gather more information about vaccines, such as the side effects and negative consequences of vaccines (Harmsen et al., 2013). Other studies have shown some association between vaccination resistance and people’s preferences for online information (Martin & Petrie, 2017).

While there is little evidence about how online information influences vaccination decisions (Meppelink et al., 2019), in their scoping review of parents’ information-seeking related to vaccines from online sources and childhood vaccination decision-making, Ashfield and Donelle (2020) found evidence of significant childhood vaccine misinformation and risks online. The authors underscore the importance of digital health literacy, which is crucial in evaluating online vaccination information. Consequently, they put emphasis on further research of parents’ “information-seeking practices, preferred resources, and ability to critically evaluate vaccination-related information” (p. 6). There is even less evidence on the information ecosystems (Susman-Peña et al., 2014) of CALD communities as they relate to vaccine decision-making. The current study inquires if members of CALD communities can obtain health information that they trust and the sources they rely on to make vaccination decisions. Understanding the contexts of the sources of health information they rely on can inform tailored packaging of vaccine-related information to ensure it appeals to and reaches targeted members of CALD communities so that they can make informed decisions about vaccination.

Literature Review

Vaccination Decision-Making

Widespread vaccination coverage is crucial to containing the COVID-19 pandemic. However, delayed acceptance or refusal to vaccinate, also referred to as vaccine hesitancy (World Health Organization, 2014), is widespread, working as a barrier to achieving the required vaccine coverage levels (Lin et al., 2021). Past research has identified concerns contributing to refusal or delayed acceptance of vaccination, including safety and effectiveness of vaccines (Kennedy et al., 2011; Freed et al., 2010), and low levels of confidence and trust in vaccine information from medical professionals, public health agencies, and the government (Gehlbach et al., 2022; Holroyd et al., 2021; Salmon et al., 2005). In terms of vaccine hesitancy, in a recent study, Marzo et al. (2022) found that almost half of the participants (N = 10,447) from 20 countries with cultural and linguistic differences, showed hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination. The level of their perceived COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, uptake decision-making, and hesitancy were significantly correlated with socio-demographic and economic characteristics, including country of residence, education, and employment. With regard to the unwillingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, available research has identified factors such as newness, safety, and potential side effects of the vaccine (Lu, 2022; Neumann-Böhme et al., 2020; Sherman et al., 2021).

Importantly, existing evidence has demonstrated that members of ethnic minority groups and with lower-income levels have more negative attitudes toward vaccines and are less willing to vaccinate against COVID-19 (Lee & Huang, 2022; Paul et al., 2021). Lower socioeconomic status was also associated with greater uncertainty and unwillingness to receive COVID-19 booster doses (Paul & Fancourt, 2022). In order to understand and address barriers to COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among CALD communities, it is important to examine determinants of vaccine decision-making in those communities to tailor public health communication programs accordingly.

There are some factors associated with vaccine decisions, including vaccine information sources. With regard to childhood immunization, parents who harbour varying vaccination attitudes regularly cited healthcare providers as the most trusted vaccine information source (Brunson 2013; Chung et al., 2017), similar to Marzo et al.’s (2022) research result that healthcare providers’ advice was the top determinant for COVID-19 vaccine decision-making. Many also revealed that they relied on a personal network such as spouses/significant others/partners, friends (Chung et al., 2017), as well as online sources to find vaccine information (Brunson, 2013; Sobo, 2015). Although several studies have been conducted focusing on vaccination decisions among parents of young children and individuals’ decision-making, there is a dearth of research on vaccination decision-making among CALD communities. Furthermore, little attention has been paid to factors such as health information sources influencing vaccine decision-making. This study aims to investigate the role of information sources in vaccine decision-making among four culturally and linguistically diverse communities—Arabic-speaking, Bengali, Chinese, and Spanish-speaking—in the U.S. Understanding health information source as a determinant of vaccine decision-making among communities with varying vaccination decisions can help inform the design of targeted and tailored interventions to increase vaccine uptake among those communities.

Social Determinants of Health and Vaccination Decisions

An individual’s ability to actively pursue and acquire vaccination is a function of the presence of certain conditions. These conditions include (a) knowledge about the vaccine through the communication of information that is clear, understandable, and relatable; and (b) ability to obtain resources including time, sense of psychological safety and security, and geographic reach.

Availability of culturally and linguistically appropriate vaccine information. The research literature posits that Hispanic adults were more likely than their white counterparts to indicate that they did not have enough information about where or when they could get vaccinated (Ohlsen et al., 2022; Pradhan, 2021). This phenomenon can partly be explained by the inability to obtain vaccine information. Silva (2021) reported that there is limited vaccine information in languages other than English. Lack of translations of available information is exacerbated by the fact that these resources are developed with a monocultural lens and fail to provide messages that would resonate with culturally diverse individuals. Cultural barriers, as Silva (2021) contends, made it difficult for immigrants and non-English-speaking communities to get COVID-19 vaccines. Overcoming barriers to vaccination mandates the development of culturally adapted messages that respond to the different understanding and cultural beliefs of disease processes and progression (Thomas et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022).

When information that is vital to obtaining life-saving vaccines is not provided in languages spoken, CALD communities often are forced to turn to non-credible information and become victims to false and inaccurate misinformation that has infested the global social media scene about the vaccine (Pradhan, 2021). Despite the vulnerabilities associated with culturally and linguistically diverse communities, information regarding vaccines in languages other than English was relatively delayed (e.g., NCDHHS, 2022). It is crucial to employ culturally and linguistically relevant methods to reach communities of colour and to tailor health information. Along these lines, Stadnick et al. (2022) identified key factors in increasing equitable COVID-19 vaccination uptake for communities of colour, that is, the development of culturally and linguistically appropriate COVID-19 programs. These programs included bilingual staff and trusted cultural and linguistic information with proper channels in the design of outreach and educational materials.

Digital literacy. Furthermore, vaccine-related materials that are disseminated through official online platforms require digital information literacy. Silva (2021) explains that on New York State’s main COVID-19 page, users have to scroll through various graphics to get to the bottom of the page, where they can click on “language access” to find other languages. If people do not know that they need to scroll down or they cannot read English, their attempts to access information will be thwarted. On a national scale, Paz et al. (2022) reported that in the top 10 most populous cities in the U.S., the number of clicks made on each Department of Health website before reaching vaccine information, locations, and registration was significantly greater for Spanish-speakers. The researchers stressed the importance of making links for vaccine registration in Spanish more readily accessible (Paz et al., 2022). It is critical that digital access to vaccine information and resources be made a priority for CALD members, as opposed to an alternative hidden behind predominantly English webpages (Caldwell, 2022).

Additionally, when translations are provided, they tend to be limited to top languages. Hotlines set up to assist in scheduling vaccine appointments tend to offer information only in English and Spanish, ignoring other languages that are commonly spoken and those that are minority languages. Thirty-nine percent of adults who have received at least one dose of vaccine indicated that they needed someone to find or schedule an appointment for them (Pradhan, 2021).

Many immigrants live in lower socioeconomic communities and may not have digital capabilities. So, they face clear hurdles to learning about the vaccination sites and scheduling of vaccine appointments (Luu, 2021). Family members of non-English speakers had to spend a significant amount of time on English-based digital portals only to constantly receive the message of “No upcoming appointments available” (Woelfel, 2021). Moreover, many communities disproportionately affected by the pandemic rely on the traditional form of oral communication when seeking and acquiring information (AuYoung et al., 2022). The lack of digital capabilities may possibly isolate community members and hinder their access to comprehendible and trusted health information about COVID-19.

Vaccine roll out has largely depended on the Internet to schedule vaccine appointments. Jameel and Chen (2021) reported that for CALD communities that do not have access to the Internet, it was much more difficult to schedule vaccine appointments.

Material and psychological resources. Limited ability to obtain material resources almost always translates to limited availability of time. Poverty of time hinders the ability to vaccinate, especially when one has to balance meeting basic needs of survival with the need for a preventive healthcare measure. Hernandez (2021) attributed lower vaccination rates among Latinos to the fact that many Latinos work hourly jobs that make accommodating vaccine appointments during the day difficult. They also face language barriers and a difficult sign-up process. While for non-English speakers, language barriers can create fear and confusion, for poor residents, it is more difficult (and more expensive) to take a few hours or a day or two off work to access vaccination (Bloch et al., 2021).

Lack of ability to obtain material resources such as private transportation can also hinder vaccination uptake. Johnson (2021) reported that immigrants had been turned away from pharmacies and other places after being asked for driver’s licenses, Social Security numbers, or health insurance cards. Even though these specific documents are not mandated by states or the federal government, they are often requested at vaccination sites across the country. These requests also are communicated in English, a language many of the vaccine-seekers do not fully understand. Only ten states and D.C., which have residency requirements, also allow undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses or state identification cards. Persaud (2021) emphasized that the lack of paperwork and identification needed for vaccination erected a barrier to vaccination.

Geographic impediments can also create an additional barrier. Vaccination rates tend to be lower for those in rural areas and those without vehicles (Lee & Huang, 2022). Thomas et al. (2021) posit that due to storage requirements of the COVID-19 vaccines, it is often difficult to reach rural areas. Migrant populations who are mobile and work in rural areas are often unable to obtain vaccinations. Unless the vaccine is brought to people where they live, geographic impediments will remain a barrier (Thomas et al., 2021). In cases where access is limited by geography, a possible alternative is to utilize trusted community partners to assist with transportation and administration (Barrett, 2022; Malone et al., 2022), and to focus on outreach strategies that bring information into communities, as opposed to relying on English-only websites (AuYoung et al., 2022).

Moreover, obtaining COVID-19 vaccination requires confidence to engage with an unfamiliar and complex healthcare system without fear of fiscal implications, apprehension produced by possible negative experiences and encounters, or threats of deportation. There is a psychological empowerment that is critical to engaging in preventive behavior; empowerment that Abraido-Lanza et al. (2007) argue may have been depleted by the relentless assault of compounding factors. They suggest that the weight of social, political, and economic factors erodes empowerment and cultivates a learned behavior of helplessness and resignation. Such learned behavior may mandate significant efforts to unlearn and restore the psychological energy that drives investment in self.

Social, economic, and psychological disempowerment produce two devastating outcomes: lack of trust and motivation to obtain vaccinations. Recent studies of COVID-19 vaccination uptake found that trust predicts vaccine uptake, and demographic characteristics including socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and educational levels, are closely associated with trust (Latkin et al., 2021).

The literature shows that the main concerns of vaccine hesitators are the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine and its longer-term side effects (Alabdulla et al., 2021; Himmelstein et al., 2022; Robertson et al., 2021). A study by Park et al. (2021) reported that 76% of participants had concerns about the vaccines. They felt that vaccine trials were conducted too quickly and were skeptical about the efficacy, necessity, and safety of the vaccine. Distrust in vaccines is intensified when considering a distrust in government institutions and the healthcare system that is prevalent in many CALD communities (AuYoung et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2021). Gonzalez et al. (2021) reported that 68% of adult immigrants in their study trusted state or local public health officials, 40% trusted elected officials in the community, 28% trusted religious leaders, and 18% trusted other sources of information. These figures are alarming considering the level of trust needed to engage in vaccine uptake.

Pre-migration experiences, medical racism, bias, and anti-immigration policies in the midst of the pandemic exacerbate distrust in CALD communities. The Trump administration’s anti-immigrant policies have exacerbated distrust in CALD communities. Numerous executive orders were enacted that targeted border enforcement and internal deportations, exclusion of many immigrants from safety net policies when they were desperately needed, and restrictions on legal refugees, immigrants, and asylum seekers (Migration Policy Institute, 2020). Such policies had devastating impacts on many in CALD communities that will require intensive trust building efforts.

As discussed above, several factors intersect to dampen motivation for vaccine uptake among many CALD communities. Lack of motivation can be a symptom of a variety of causes, including English language barriers, lack of material and psychological resources, and lack of trust. Nevertheless, lack of motivation can also be an independent root cause that hinders vaccine uptake in many CALD communities. Khatib et al. (2014) suggest that intention barriers (e.g., low motivation, low self-efficacy) are associated with poor hypertension prevention and management.

Lack of motivation can be a function of a feeling of invincibility and an expression of a sense that “I am healthy, I will not get sick, my body is resilient” or it can be a deeply rooted religious belief that pursues reliance only on protection from the divine.

Notwithstanding religious prohibition against vaccination, in many traditional faith communities, resignation to the will of God is an element of worship, and a sense of fatalism is encouraged in several faith traditions. “Fatalism, the belief that health is predetermined by fate, relates to poorer adoption of risk-reducing health behaviors” (Gutierrez et al., 2017, p. 271). The belief that nothing can be done to prevent cardiovascular disease or cancer is more likely among Hispanics/Latinos than non-Hispanic Whites (Christian et al., 2007; Niederdeppe & Levy, 2007). Negative behaviours such as low utilization of cancer screening services, low utilization of protective measures against cardiovascular disease, and low adoption of behaviors such as avoidance of smoking, exercising, and healthy diets are associated with fatalistic beliefs (de Los Espinosa Monteros & Gallo, 2011; Mosca et al., 2006; Niederdeppe & Levy, 2007). Promoting an internal locus of control over health behaviours can contribute to addressing the harmful consequences of fatalistic behaviours. Faith-based interventions have been used to increase African American religious communities’ engagement in health-promoting behaviours. They have been used to increase cancer knowledge, decrease cancer fatalism, and overall “cancer activism” (Morgan et al., 2008, p. 237).

Methods

This study forms part of a larger project investigating the efficacy of innovative health communication strategies focused on educating CALD individuals about public health protective measures to combat COVID-19. Employing a mixed-methods approach, online survey and one-on-one interview data were collected in two sequential phases with a pre- and post-test and post-test-only design. The current study analyzes survey data to explore the role of information sources in vaccine decision-making among four diverse communities in the U.S. Specifically, three research questions guided this study:

- RQ1::

-

Does the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19 differ across the members of the four CALD communities?

- RQ2::

-

Can the members of the four CALD communities find health information that they trust? Is there any difference between their ability to find health information that they trust and their vaccination status?

- RQ3::

-

What health information sources do COVID-19 vaccinated and intended-to-be vaccinated members of the four CALD communities use on a regular basis? How does this health information use compare across the members of these communities?

Sample and Procedures

In the larger project, CALD individuals from four communities in the U.S.—Arabic-speaking, Bengali, Chinese, and Spanish-speaking—were invited to complete an online survey that measured their knowledge, attitude, and practice (Zhong et al., 2020), information sources (Babalola et al., 2020), and vaccine decisions (Larson et al., 2015) pertaining to COVID-19. A total of 318 participants in the current study completed the vaccine decisions survey questions. Participants were recruited through a combination of strategies, including partnership through target community-based organizations; e-mail messages and letters of information; and social media postings. Eligible participants self-identified as 18 years of age or older, foreign-born and currently living in the U.S., and primarily speaking Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, or Spanish.

The survey links were emailed to community partners for distribution among interested CALD individuals in the target communities. The primary survey in English was translated into the four languages (i.e., Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, and Spanish) representing the four participating CALD communities. Participants had the option to choose the language of the survey. From March to June, 2021, the survey was hosted on Qualtrics, a web-based survey tool. The survey was pilot tested with six individuals representing the four languages spoken by the sample to assess the readability and clarity of survey questions. A total of 318 participants in the current study completed the vaccine decisions survey questions. Each participant was offered a $20 Walmart eGift card as compensation for completing the survey. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University at Albany, State University of New York.

Measures

To determine the general characteristics of study participants, ten socio-demographic questions were used: gender, age, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, yearly household income, housing condition, length of residence in the U.S., citizenship status, and language spoken at home. Participants’ decision to vaccinate against COVID-19 was determined by their vaccination status, which was measured by the question: “Have you received the COVID-19 vaccination?” Response options included: “yes,” “intend to,” or “no.” Participants’ ability to find health information that they trust was measured by the question: “Overall, do you think you can find information about health that you trust?” Response options included: “yes,” “no,” or “maybe.” To determine health information sources used on a regular basis, participants were asked to check all that applied from nine options: “print media in my language,” “digital media in my language,” “ethnic TV and radio channels, “community leaders,” “community organizations,” “faith based organizations,” “friends and family,” “social media,” and “other (please specify):________.”

Data Analysis

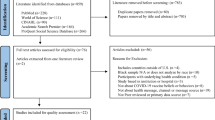

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic variables. To address RQ1, the number of participants for the total sample, and each CALD community, was calculated by their decision to vaccinate to identify differences across community groups (see Fig. 13.1). Vaccination status was assessed via the question “Have you received the COVID-19 vaccine?” To address RQ2, the number of participants for the total sample, and each CALD community, was calculated by their ability to find health information that they trust, to identify differences across community groups (see Table 13.2). To further explore participants’ ability to find health information that they trust, subgroups of participants were calculated based on their decision to vaccinate (see Fig. 13.2). RQ3 focuses only on participants who reported that they had been vaccinated or intended to vaccinate as a subgroup. To address RQ3, the information sources these participants used were calculated for the total subgroup and in each CALD community. Sources of health information used were classified according to Street’s (2003) ecological model, by mapping information source items to the communication contexts (e.g., “Media Context,” “Organizational Context,” and “Interpersonal Context”) (see Table 13.3). All calculations (and charts) were performed in Excel and cross-checked by members of the research team.

Findings and Analysis

Selected Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Each of the four CALD communities is well-represented among the 318 survey participants (see Table 13.1). Members of the Arabic-speaking community, however, are slightly more represented (at 33.0%).

Gender. In the total sample, individuals identifying as females are more represented (at 65.7%). Females are over-represented in the Chinese community (66.7%), the Spanish-speaking community (59.2%), and especially in the Arabic-speaking community (90.5%). However, individuals identifying as females in the Bengali community are less represented (at 40.3%).

Age. Across the sample, those between the age of 30–39 are most represented (at 40.3%). This group was most represented in the Arabic-speaking community (35.2%), the Bengali community (35.1%), and the Spanish-speaking community (57.9%). In the Chinese community, individuals between the age of 40–49 were most represented (at 48.3%). In all communities, individuals over the age of 70 were underrepresented.

Marital status. Across the sample, most participants reported being married (at 84.6%). In all four CALD communities, too, married individuals are most represented.

Educational attainment. The sample varied in terms of educational attainment. Across the sample, slightly more than half of the participants had at least post-secondary education (at 55%). Most participants from the Arabic-speaking community had less than a high school degree (at 64.8%). Less than half of participants had at least a bachelor’s degree. More than half of participants from the Spanish-speaking community had at least a bachelor’s degree, and more than half from the Chinese community had a graduate or a professional degree.

Employment status. Across all four CALD communities, most participants identified as homemakers (at 44.0%). Relatively fewer participants were employed, most of whom were employed for salary (at 18.6%), and fewer were self-employed (at 1.6%). In contrast, 28.6% of the sample reported not working for various reasons (e.g., “out of work and looking,” “unable to work,” and so on).

Yearly household income. Across the sample, yearly household income was fairly distributed, though over a quarter of participants preferred not to answer (at 25.8%), many of whom were in the Arabic-speaking community (representing 73.2% of those who preferred not to answer). For the entire sample, 32.0% of participants reported a yearly household income of $29,999 or less. This pattern was consistent for all but the Chinese community (18.3%), with slightly fewer represented as lower-income. Most individuals in the Chinese community made a yearly household income of $80,000 or more.

Housing condition. Housing condition in the sample was somewhat split, though slightly more individuals reported living in owner-occupied housing (54.4%). Differences in housing conditions emerged between communities, with those in the Bengali (at 68.8%), Chinese (at 83.3%), and Spanish-speaking (at 71.1%) communities more represented in owner-occupied housing. Individuals in the Arabic-speaking community were more represented in rent-occupied housing (at 81.0%).

Length of residence in the U.S. For the majority of the sample, participants reported having resided in the U.S. for more than five years (63.8%). This pattern was consistent across all CALD community groups, though individuals in the Arabic-speaking community were less represented (at 48.6% for over five years of residence) and slightly more residing three to five years (at 25.7%). Cumulatively, over a third of participants in the sample reported residence for less than five years (at 35.2%).

Naturalized U.S. citizen. The total sample contained a good portion of naturalized U.S. citizens (61.6%) and a relatively small number of non-U.S. citizens (37.7%). The Spanish-speaking community (84.2%) and the Bengali community (83.1%) reported nearly twice as many U.S. citizens as the Chinese community (41.7%) and the Arabic-speaking community (41.0%). More than half of the individuals from the Chinese community (58.3%) and the Arabic-speaking community (58.1%) were non-U.S. citizens.

Language spoken at home. Most participants spoke both English and their primary language (48.7%) at home, as compared to those who spoke only their primary language (32.1%) or English (19.2%). Across all four CALD communities, individuals who spoke only their primary language at home were most represented by the Arabic-speaking (at 46.7%) and Chinese communities (at 48.3%), and individuals who spoke only English at home were most represented by the Bengali community (at 48.1%).

Vaccination Status Across CALD Communities

The first research question is concerned with differences across the members of the four CALD communities in their decision to vaccinate against COVID-19. The survey findings show that over a third (39.3%) of participants across the four CALD communities reported receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, with another quarter (25.2%) reported having an intention, while one third (35.5%) reported not receiving a vaccine (see Fig. 13.1). In other words, the largest proportion of the four participating CALD community members either decided to or planned to vaccinate against the risk of contracting COVID-19. Nevertheless, important variations exist when looking at the vaccination status in each community. For example, in the Spanish-speaking community, 58.4% reported receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, with another 29.9% reported having an intention, while only 9% reported not receiving a vaccine. In the Chinese community, 35% reported receiving a COVID-19 vaccine with another 36.7% reported having an intention, while 28.3% reported not receiving a vaccine. On the contrary, in the Arabic-speaking community, the largest proportion of survey participants (75.2%) reported not receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, with 21% reported having an intent and only 3.8% reported receiving a vaccine.

In summary, the findings indicate that there are differences across these four CALD communities in the rates at which they have been vaccinated or report the intention to be vaccinated. It may be the case that even though these groups may all represent culturally and linguistically diverse communities, particular language groups might find that messaging and communication are readily available in their native language (e.g., Spanish) as compared to those who predominantly speak other languages (e.g., Arabic). The rate at which individuals seek to obtain a vaccine or express the intention to do so might reside with their access to vaccines and exposure to information in their native or dominant language that would inform them on how to go about engaging in participation in vaccination sites and healthcare institutions. These findings would suggest that the expansion of materials and messaging related to acquiring vaccines need to appear in multiple languages and be culturally congruent with CALD communities, particularly those who stem from groups that represent linguistic minority speakers.

Ability to Find Trusted Health Information by Vaccination Status

The second research question is concerned with the ability of the members of the four CALD communities to find health information that they trust and any difference between their ability to find health information that they trust and their vaccination status.

The survey findings indicate that two-thirds (66.7%) of participants across the four CALD communities can find health information that they trust (see Table 13.2), with variation in the response rate among the individual communities: Spanish-speaking (85.5%), Bengali (81.8%), Chinese (68.3%), and Arabic-speaking (41.0%). It is important to note that only 4.1% of participants across the four communities reported that they could not find health information they trust, with little variation among the communities: Bengali (2.6%), Chinese (3.3%), Spanish-speaking (3.9%), and Arabic-speaking (5.7%). However, close to a third of participants (28.9%) across the four communities seem to be unsure about finding health information they trust, with variation among the communities: Arabic-speaking (52.4%), Chinese (28.3%), Bengali (15.6%), and Spanish-speaking (10.5%).

Relatedly, community members who are more likely to obtain a vaccine or show a high likelihood of their intention to do so also represent a community where their language may be more readily spoken (e.g., Spanish). As Spanish is one of the most highly spoken languages in the U.S., it is likely that Spanish-speaking communities have been exposed to messages and communication in their dominant language and trust the source and content of that information enough to promote action within these communities. Other cultural factors can also contribute to building a community’s trust in vaccines, such as the status, gender, or perceived authority of the individuals communicating those messages to the members of the community (e.g., esteemed religious figures, medical personnel, and so on). With increased dissemination of knowledge in the dominant language of CALD communities, one might expect an increase in the trust or perceived value of the information being communicated, which can then promote an increase in actually obtaining a vaccine or having an intention to do so.

Ability of vaccinated participants to find health information that they trust. The survey findings provide important information regarding the association between participants’ ability to find health information they trust and their vaccination status (see Fig. 13.2). For example, an overwhelming majority (81.6%) of participants who received a COVID-19 vaccine reported that they could find health information they trust, with more variation among the four communities: Spanish-speaking (96.4%), Bengali (75.6%), Chinese (66.7%), and Arabic-speaking (25.0%). It is worth noting that only a small proportion of vaccinated participants (2.4%) across the four communities reported that they could not find health information they trust. There was little variation among the four communities: Bengali (4.4%), Spanish-speaking (1.8%), Arabic-speaking (0.0%), and Chinese (0.0%). However, 16.0% of this subgroup of participants seem to be unsure about finding health information they trust, with many variations among the communities: Arabic-speaking (75.0%), Chinese (33.3%), Bengali (20.0%), and Spanish-speaking (1.8%).

These findings are consistent with other reported findings in the current chapter, namely, as information is more readily available in the native language of a CALD community member, the more likely that individual is to trust that information and engage in positive health-related behaviors. Across all communities, individuals report that they can locate trusted health information to make decisions about the vaccine at a rate that approaches 82%; however, those in the Spanish-speaking community report that they can find trusted information at a rate that is well above average, likely because information in Spanish is more readily available than in other languages. These findings imply that if messaging and communication are provided in other languages that are spoken by CALD communities in a culturally relevant manner, it is more likely that members of those communities will seek vaccination, trust the source of information regarding their health, and follow through when intending to seek health care. Thus, providing healthcare information in multiple languages is critical to increasing the overall rate of vaccination and in perpetuating trust in the source and content of healthcare information.

Ability of intended-to-be vaccinated to find health information that they trust. The survey findings suggest that two-thirds (66.3%) of participants who intended to receive a COVID-19 vaccine reported finding health information they trust, with important variation across the groups: Bengali (87.0%), Chinese (72.7%), Spanish-speaking (53.8%), and Arabic-speaking (45.5%). Similar to participants who received a COVID-19 vaccine, a limited number of participants with an intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine (5.0%) reported that they could not find health information they trust, with some variation among the four communities: Spanish-speaking (15.4%), Arabic-speaking (4.5%), Chinese (4.5%), and Bengali (0.0%). Nevertheless, 28.8% of this subgroup of participants appear to be unsure about finding health information they trust, with some variation among the communities: Arabic-speaking (50.0%), Spanish-speaking (30.8%), Chinese (22.7%), and Bengali (13.0%).

Overall, it appears that a majority of participants who intended to receive a vaccine reported that they were able to find health information that they trusted. While this is a positive outcome of the current study, it is still the case that this value only represents roughly two-thirds of the overall set of participants. Thus, there is a likelihood that the remaining participants, though expressing an intention to be vaccinated, may not follow through on those intentions merely because they may not trust the information that they have received. It is possible that the information may have been provided in a language other than their native or dominant language, or, perhaps it was presented in a way that is not culturally sensitive in some manner, causing individuals to hesitate to follow through on their intentions. In effect, the fact that nearly 30% of the population that engaged in this study were uncertain as to whether or not they could find health information that they trusted to make a decision about the vaccine indicates that perhaps linguistic or cultural variables directly impacted the perceived validity of the information and thereby could have created vaccine hesitancy among those participants.

Ability of unvaccinated participants to find health information that they trust. Based on the survey findings, it is interesting to note that half (50.4%) of the participants who reported not receiving a COVID-19 vaccine can find health information they trust, with important variation among the four CALD communities: Bengali (100.0%), Chinese (64.7%), Spanish-speaking (62.5%), and Arabic-speaking (40.5%). It is also interesting to note that similar to participants who received and were intending to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, very few participants (5.3%) who did not receive a COVID-19 vaccine reported that they could not find health information they trust, with some variation among the four communities: Arabic-speaking (6.3%), Chinese (5.9%), Bengali (0.0%), and Spanish-speaking (0.0%). Notwithstanding this, it is important to note that a large number (43.4%) of this subgroup of participants happen to be unsure about finding health information they trust, with many variations among the communities: Arabic-speaking (51.9%), Spanish-speaking (37.5%), Chinese (29.4%), and Bengali (0.0%).

Overall, about half of the participants in the current study who did not receive a vaccine reported that they could find health information that they trusted to help decide about the COVID-19 vaccine. Even though this was the case, at the time of their participation, they still had not gotten a vaccine and did not report having an intention to do so. Thus, there is a likelihood that other factors above and beyond the perceived notion of trust might have moderated their hesitancy or decision not to engage in the vaccination process at all. With CALD communities, it is possible that cultural aspects that are not related to the trustworthiness of the information at all, or even the language in which it appears, could moderate vaccine-related behavior. For example, individuals may feel that a vaccine may not be warranted, as all of one’s health or well-being is ultimately controlled by a higher power or that an outcome cannot be changed. Some beliefs or faith overall may encourage the notion that health outcomes are more readily determined by one’s destiny, which is already preordained. All this said, it is important to point out that the other half of participants who noted they did not receive a vaccine indicated that they were unsure whether or not they were able to find the information they trusted or, indeed, were not able to find such information. Thus, the hesitancy or decision of this group to not engage in vaccination might stem from the notion of perceived trust in the information that could be derived by either the source of information, some aspect of its contents (e.g., language in which it appeared or cultural scheme within which it appeared) or indeed a variable such as an inability to comprehend information because it appeared in a language in which they had limited knowledge or experience. Detailed investigations of the role, nature, and scope of the sources of health-related information should be undertaken with CALD communities to understand more precisely how the nature, type, and delivery of information impact trust, which could indeed impact vaccine hesitancy or acceptance.

In summary, the current research findings suggest a few trends for the CALD communities under consideration and their responses concerning vaccination acceptance or hesitancy and trust in the source of health information. First, these data reveal that culturally and linguistically appropriate healthcare information and the existence and dissemination of that information may increase an individual’s willingness to get vaccinated and may increase trust in the source of health information. The recommendation here is to expand existing materials across languages and in culturally appropriate ways to increase an understanding of the importance of vaccination, particularly during COVID-19. Second, it is clear that the Spanish language in particular, a predominant language in the U.S., is one in which health-related information can already be found, thus impacting the degree to which Spanish-speaking communities engage in vaccination and record lower vaccine hesitancy. Addressing the earlier recommendation of expanding information across different languages should serve to likewise increase vaccine acceptance in other CALD communities, leading to an overall decrease in vaccine hesitancy. Finally, vaccine hesitancy or the decision not to vaccinate at all may stem from a lack of trust in available health information, either due to the information’s lack of cultural or linguistic match with the background of a particular community, or because the source was not considered credible. Future research should continue to examine the nature of the source of information and the variables that help to determine how they promote trust and adherence, so as to further increase the probability that individuals will seek vaccination and acceptance of public health guidance in general.

Health Information Source Use by Vaccinated and Intended-to-Be Vaccinated Participants Across CALD Communities

The third research question is concerned with the health information sources COVID-19 vaccinated and intended-to-be vaccinated members of the four CALD communities use regularly and how that compares across the members of these communities. Survey participants who reported receiving and intending to receive a COVID-19 vaccine were asked to identify the health information sources they use regularly. Based on their responses, these sources can be categorized into three communication contexts (Street’s [2003] ecological model of communication [see Table 13.3]: media, organizational, and interpersonal).

Media context of health information sources. The survey findings demonstrate that out of the four types of media sources, digital media in native language have the highest rate (52.2%) of use across the four CALD communities with variation among the communities: Chinese (72.1%), Spanish-speaking (48.5%), Bengali (47%), and Arabic-speaking (42.3%). The use of ethnic TV and radio channels (42.9%) ranks second across the communities, with some variation: Spanish-speaking (54.4%), Bengali (48.5%), Arabic-speaking (34.6%), and Chinese (20.9%). The use of social media (42.9%) is tied for the second rank with some variation among the communities as well: Arabic-speaking (65.4%), Bengali (42.6%), Spanish-speaking (38.2%), and Chinese (37.2%). With a slightly lower rate (40.0%), the use of print media in native language varies among the Arabic-speaking (57.7%), Bengali (39.7%), Spanish-speaking (39.7%), and Chinese (30.2%).

In summary, these findings suggest that among the CALD communities included in the current study, digital media in the native language is the most typical source of health information, including health-related information. Given that individuals often use hand-held devices such as smartphones to communicate with others and gain knowledge, it is not unusual to expect that digital sources provide most individuals with news and information, particularly in their native language. The notion that ethnic TV and radio are other sources for health information indicates that again, for CALD communities, information that is available in their native language is often sought and considered more readily than information that is perhaps not as culturally or linguistically relevant, as in the case of information provided only in English. Thus, to reach these populations with health-related information that they are likely to consult and use on a regular basis, having that information appear in their native language is probably the best way to assure that the information is read and considered in decision-making, in the current context, vaccine decision-making. Interestingly, the notion that Arabic-speaking community members accrue to print media more readily than the other groups in the current study speaks to the notion that perhaps this is the more accessible format or source appearing in the Arabic language for the current communities. Thus, there is a call for health information to be presented across languages in various formats but assuring that digital and other related media sources make this information available in culturally and linguistically appropriate ways.

Organizational context of health information sources. With regard to the use of health information in the organizational context, survey participants across the four CALD communities reported relying on community organizations the most (37.6%), with many variations among the communities: Bengali (45.6%), Arabic-speaking (42.3%), Spanish-speaking (41.2%), and Chinese (16.3%). Community leaders (26.3%) are other sources of information across the four communities with substantial variation among the communities: Chinese (0.1%), Bengali (22.1%), Spanish-speaking (38.2%), and Arabic-speaking (38.5%). It should be noted that faith-based organizations (24.9%) are closely tied with community leaders as sources of health information across the four communities with noteworthy variation among the communities: Spanish-speaking (36.8%), Arabic-speaking (26.9%), Bengali (26.5%), and Chinese (2.3%).

The data on organizational contexts as sources of health information indicate that most members of these CALD communities rely on community organizations for finding health-related information. Clearly, the importance of networking and communicating within a group of individuals who are like-minded and share a set of values and beliefs cannot be underestimated. Moreover, these communities rely on faith-based organizations, particularly within the Spanish- and Arabic-speaking communities where religion plays a predominant role in shaping worldviews and influences the context in which members receive and comprehend information that impacts their decision-making. Trust in these sources plays a vital role in shaping the thoughts and beliefs of community members, particularly with respect to mental and physical health and well-being.

Interpersonal context of health information sources. As interpersonal sources of health information, friends and family are dominant (42.0%) across the four CALD communities with very little variation among the communities: Bengali (50.0%), Arabic-speaking (42.3%), Chinese (39.5%), and Spanish-speaking (35.3%).

The current survey findings suggest that these individuals, as one might expect, do rely heavily on interpersonal sources of health information such as that gathered from close family relations and friends. This finding appears pervasive across all of the four CALD communities surveyed, and indeed, with communities that represent collectivist cultural mores, it is not uncommon to note that individuals rely on interpersonal and intercultural communication as sources of information. Most importantly, these interactions can influence and guide healthcare decisions and the interpretation of data or information provided across media sources and help convert those notions into action. Moreover, it is often the case that individuals follow the information derived from their immediate cultural groups to be part of that “in-group” experience and demonstrate an affinity with the group, expressing the importance of their membership and allegiance to the culture at hand. These findings underscore the power of culturally and linguistically appropriate and valid information in informing and motivating behavior change and the selection of individuals to engage in certain healthcare options such as vaccination and disease prevention.

Discussion

The findings reported in this chapter provide comparative insights into the perceived trust of health information that participating members of four CALD communities in the U.S. obtain and the sources of health information they use that shape their COVID-19 vaccination decisions.

The picture that emerged is that Arabic-speaking participants have the lowest rates of vaccination (3.8%), followed by the Chinese participants (35%), Bengali (58.4%), and Spanish-speaking (72%). Arabic-speaking participants are more likely to indicate no intention to receive vaccination (75.2%), followed by the Chinese participants (28.3%), Bengali (11.7%) and Spanish-speaking (10.5%). Obviously, the critical mass of Spanish-speaking communities has the advantage of increasing the likelihood of finding information that is culturally and linguistically appropriate. In fact, most formal venues of vaccine communications in the U.S. are available in English and Spanish, including hotlines. Outreach to the Spanish-speaking communities through Spanish-speaking community-based organizations and through targeted culturally and linguistically sensitive resources can explain the high vaccination and intention to vaccinate rates in the Spanish-speaking community. However, what explains the high vaccination rates in the Bengali survey participants and the low rates in the Arabic and Chinese-speaking participants by comparison? Is it a lack of trust in the healthcare establishment? Or is it a lack of an ability to obtain information one trusts?

The diverse socio-demographic characteristics of survey participants can provide possible answers that are consistent with the literature on COVID-19 vaccination. On the one hand, the Arab and Chinese-speaking participants had a large proportion of individuals who spoke a language other than English (46.7 and 48.3% respectively), while the Bengali participants were mostly English speakers (48%). High rates of non-citizens were also prevalent in the Arabic and Chinese-speaking survey participants (58.1 and 58.3% respectively). In comparison, the Spanish and Bengali-speaking participants had high rates of naturalization (84.2 and 83.1% respectively). Approximately 65% of Arabic-speaking participants reported low educational attainment, 66% were homemakers, 90.5% were female, 49% indicated a length of stay less than 5 years, and 81% lived in rent-occupied housing. The Arabic-speaking participants and to a great extent their Chinese counterparts faced multiple layers of vulnerabilities when compared to their Spanish and Bengali-speaking counterparts, which most probably meant lower health literacy, and decreased access to health and social services, opportunity structures and other adverse social determinants of health.

The findings of this study are consistent with other research results on the impact of socioeconomic status on health information seeking, confidence, and trust. Richardson et al. (2012), for example, show that lower educational attainment and lower-income are associated with reduced information-seeking behavior and trust in doctors and other healthcare providers. Dimensions of the sociopolitical and cultural environment may also shape attitudes and decisions to engage with the healthcare system.

Implications

The number of confirmed and presumptive positive cases of COVID-19 disease recorded in the U.S. had surpassed 94 million as of September 4, 2022, with over one million deaths among these cases. As of the same date, more than 809.9 million doses of the COVID-19 vaccine were delivered, and more than 610 million doses were administered with 224.1 million individuals fully vaccinated (amounting to 67.5% of the population), 108.8 million received their first booster dose, and 22 million received their second booster dose in the U.S. (CDC, 2022). To manage and end the pandemic, higher vaccination coverage against COVID-19 will be required. It is of paramount importance to examine individuals’ intention to be vaccinated, especially among priority groups, so that targeted health messages and strategies can be tailored to boost the public’s confidence in COVID-19 vaccinations.

According to the CDC Internet panel survey (n = 3541) in 2020 to assess baseline perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine and intentions to get vaccinated among priority groups, lack of COVID-19 vaccine confidence, side effects, and safety concerns about the vaccine were reported, and varied by demographic characteristics, including age group, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, household income level, region, Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA status), urbanicity, and health insurance status.

Within the backdrop of the increased health risks and challenges that CALD communities face during the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings of the current study bear important implications for policy and practice. Obtaining trusted health information contributed to COVID-19 vaccination decisions among members of the four participating CALD communities. Vaccine recipients in this study rely on multiple sources of information to protect themselves and their families. Healthcare providers and policymakers should target health information sources trusted by CALD communities for COVID-19 vaccine communication to these groups.

Adverse social determinants of health across different dimensions and levels of influence emerge as strong predictors of ability to obtain vaccination and decision to vaccinate. As emphasized in this chapter, socioeconomic status and educational attainment hinder the ability of individuals to obtain information that they trust and decrease the likelihood that they can obtain vaccination. Availability of culturally and linguistically appropriate resources and outreach to communities that are adversely affected by limited English proficiency and poverty is critical to the fight against COVID-19 and vaccine uptake goals. Finally, this study points to sources of information that are trusted by people who have chosen to vaccinate in the four participating CALD communities. These information sources can be more effectively leveraged to achieve increased diffusion of vaccine information and greater vaccine uptake, as well as mitigation of future health crises and effective dissemination of critical public health messages in general.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The findings of this study should be considered in light of a number of limitations. First, the sample of four CALD communities is not representative of the entire population of CALD communities in the U.S. Hence, future research should strive to expand the sample size to recruit members of other CALD communities and account for any differences in the use of health information sources that may relate to the context and history of settlement. Second, there was a low representation of older individuals in the survey participant sample. This may be due to limited digital literacy and may mask a bleaker picture especially in communities where members have low English language proficiency, low documentation status, and higher vulnerability to COVID-19. Accordingly, future research should recruit a more diverse sample. Third, the study used descriptive statistics, hence, findings cannot extend beyond summarizing emerging patterns of participants’ self-reported vaccination status, trusted health information obtained, and health information source use across the communities in shaping their vaccine decision-making. Future research should utilize complementary inferential statistics to make conclusions about relevant hypotheses, and thereby provide a more in-depth understanding of health information use practices of CALD communities by also examining their access to these sources and ability to understand and use the information to make informed vaccine and other preventive health decisions. It is also recommended that qualitative methods such as focus groups be employed with CALD communities to gain deeper insights into the influence of health information sources used by these communities for making vaccination decisions.

References

Abba-Aji, M., Stuckler, D., Galea, S., & McKee, M. (2022). Ethnic/racial minorities’ and migrants’ access to COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. Journal of Migration and Health, 100086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100086.

Abraido-Lanza, A. F., Viladrich, A., Florez, K. R., Cespedes, A., Aguirre, A. N., & De La Cruz, A. A. (2007). Fatalismo reconsidered: A cautionary note for health-related research and practice with Latino populations [Commentary]. Ethnicity and Disease, 17(1), 153–158. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17274225.

Alabdulla, M., Reagu, S. M., Al‐Khal, A., Elzain, M., & Jones, R. M. (2021). COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in Qatar: A national cross‐sectional survey of a migrant‐majority population. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 15(3), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12847.

Ashfield, S., & Donelle, L. (2020). Parental online information access and childhood vaccination decisions in North America: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(10), Article e20002. https://doi.org/10.2196/20002.

AuYoung, M., Rodriguez Espinosa, P., Chen, W.-T., Juturu, P., Young, M.-E. D. T., Casillas, A., Adkins-Jackson, P., Hopfer, S., Kissam, E., Alo, A. K., Vargas, R. A., Brown, A. F., & And the STOP COVID-19 C. A. Communications Working Group. (2022). Addressing racial/ethnic inequities in vaccine hesitancy and uptake: Lessons learned from the California alliance against COVID-19. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-022-00284-8.

Babalola, S., Krenn, S., Rimal, R., Serlemitsos, E., Shaivitz, M., Shattuck, D., & Storey, D. (2020). KAP COVID Dashboard.Johns Hopkins center for communication programs, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Global outbreak alert and response network, Facebook Data for Good. Published September 2020. Data Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://ccp.jhu.edu/kap-covid/.

Barrett, C. (2022, March 3). How a rural hospital broke language barriers to provide COVID vaccines to immigrants. WFYI. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://www.wfyi.org/news/articles/seymour-rural-hospital-language-barriers-covid-vaccines-immigrants.

Batalova, J. (2020, May 14). Immigrant health-care workers in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigrant-health-care-workers-united-states-2018.

Bebinger, M. (2021, April 22). The pandemic imperiled non-English speakers in a hospital. NPR. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/04/23/989928262/the-pandemic-imperiled-non-english-speakers-in-a-hospital.

Bloch, M., Buchanan, L., Holder, J. (2021, March 26). See who has been vaccinated so far in New York City. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/03/26/nyregion/nyc-vaccination-rates-map.html.

Borjas, G. (2020, April). Demographic determinants of testing incidence and COVID-19 infections in New York City neighbourhoods. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w26952 Article 26952. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26952.

Brunson, E. K. (2013). The impact of social networks on parents’ vaccination decisions. Pediatrics, 131(5), e1397–e1404. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2452.

Caldwell, A. (2022, February 9). Spanish language vaccine resources harder to access, while Hispanic vaccination rates remain below overall average, study finds. At the Forefront UChicagoMedicine. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/research-and-discoveries-articles/spanish-language-vaccine-resources-harder-to-access.

Certified Languages International. (2021, January 25). How trust can help combat vaccine hesitancy among non-English speakers. Certified Languages International. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://certifiedlanguages.com/blog/combat-vaccine-hesitancy-among-non-english-speakers/.

CDC. (2022, September 9). COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.

Christian, A. H., Rosamond, W., White, A. R., & Mosca, L. (2007). Nine-year trends and racial and ethnic disparities in women’s awareness of heart disease and stroke: An American Heart Association national study. Journal of Women’s Health, 16, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.M072.

Chung, Y., Schamel, J., Fisher, A., & Frew, P. M. (2017). Influences on immunization decision-making among US parents of young children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(12), 2178–2187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2336-6.

de Los Espinosa Monteros, K., & Gallo, L. C. (2011). The relevance of fatalism in the study of Latinas’ cancer screening behavior: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18, 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-010-9119-4.

Freed, G. L., Clark, S. J., Butchart, A. T., Singer, D. C., & Davis, M. M. (2010). Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics, 125(4), 654–659. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1962.

Gehlbach, D., Vázquez, E., Ortiz, G., Li, E., Sánchez, C. B., Rodríguez, S., Pozar, M., & Cheney, A. M. (2022). Perceptions of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 testing and vaccination in Latinx and Indigenous Mexican immigrant communities in the Eastern Coachella Valley. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13375-7.

Gonzalez, D., Karpman, M., & Bernstein, H. (2021, April). COVID-19 vaccine attitudes among adults in immigrant families in California. Urban Institute. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103973/covid-19-vaccine-attitudes-among-adults-in-immigrant-families-in-california_0.pdf.

Gutierrez, A. P., McCurley, J. L., Roesch, S. C., Gonzalez, P., Castañeda, S. F., Penedo, F. J., & Gallo, L. C. (2017). Fatalism and hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in US Hispanics/Latinos: Results from HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 271–280.

Harmsen, I. A., Mollema, L., Ruiter, R. A., Paulussen, T. G., de Melker, H. E., & Kok, G. (2013). Why parents refuse childhood vaccination: A qualitative study using online focus groups. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1183.

Hernandez, E. (2021, April 19). Denver says it wants to help more Latinos get the COVID vaccine. Data shows that’s not happening. Denverite. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://denverite.com/2021/04/19/denver-says-it-wants-to-help-more-latinos-get-the-covid-vaccine-data-shows-thats-not-happening/.

Himmelstein, J., Himmelstein, D. U., Woolhandler, S., Dickman, S., Cai, C., & McCormick, D. (2022). COVID-19–related care for Hispanic elderly adults with limited English proficiency. Annals of Internal Medicine, 175(1), 143–145. https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-2900.

Holroyd, T. A., Howa, A. C., Delamater, P. L., Klein, N. P., Buttenheim, A. M., Limaye, R. J., Proveaux, T. M., Saad, B. O., & Salmon, D. A. (2021). Parental vaccine attitudes, beliefs, and practices: Initial evidence in California after a vaccine policy change. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 17(6), 1675–1680. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1839293.

Jameel, M., & Chen, C. (2021, March 1). How inequity gets built into America’s vaccination system. ProPublica. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.propublica.org/article/how-inequity-gets-built-into-americas-vaccination-system.

Johnson, A. (2021, April 10). For immigrants, I.D.s prove to be a barrier to a dose of protection. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/04/10/covid-vaccine-immigrants-id/.

Kennedy, A., Basket, M., & Sheedy, K. (2011). Vaccine attitudes, concerns, and information sources reported by parents of young children: Results from the 2009 HealthStyles survey. Pediatrics, 127(Supplement 1), S92–S99. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1722N.

Khatib, R., Schwalm, J. D., Yusuf, S., Haynes, R. B., McKee, M., Khan, M., & Nieuwlaat, R. (2014). Patient and healthcare provider barriers to hypertension awareness, treatment and follow up: A systematic review and meta-analysis of qualitative and quantitative studies. PloS One, 9(1), e84238.

Larson, H. J., Jarrett, C., Schulz, W. S., Chaudhuri, M., Zhou, Y., Dube, E., Schuster, M., MacDonald, N. E., Wilson, R., & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy, 2015 Larson, H. J., Jarrett, C., Schulz, W. S., Chaudhuri, M., Zhou, Y., Dube, E., Schuster, M., MacDonald, N. E., Wilson, R., & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. (2015). Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine, 33(34), 4165–4175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037.

Latkin, C. A., Dayton, L., Yi, G., Colon, B., & Kong, X. (2021). Mask usage, social distancing, racial, and gender correlates of COVID-19 vaccine intentions among adults in the US. PLoS One, 16(2), Article e0246970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246970.

Lee, J., & Huang, Y. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The role of socioeconomic factors and spatial effects. Vaccines, 10(3), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030352.

Lin, C., Tu, P., & Beitsch, L. M. (2021). Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines, 9(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016.

Lu, J. G. (2022). Two large-scale global studies on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over time: Culture, uncertainty avoidance, and vaccine side-effect concerns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000320.

Luu, L. (2021, March 4). How pharmacists can assist patients with limited English proficiency. GoodRX. https://www.goodrx.com/blog/pharmacist-resources-for-limited-english-proficient-populaitons/.

Malone, B., Kim, E., Jennings, R., Pacheco, R. A., & Kieu, A. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine distribution in a community with large numbers of immigrants and refugees. American Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 393–396. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306608.

Martin, L. R., & Petrie, K. J. (2017). Understanding the dimensions of anti-vaccination attitudes: The vaccination attitudes examination (VAX) scale. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(5), 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9888-y.

Marzo, R. R., Ahmad, A., Islam, M. S., Essar, M. Y., Heidler, P., King, I., Thiyagarajan, A., Jermsittiparsert, K., Songwathana, K., Younus, D. A., El-Abasiri, R. A., Bicer, B. K., Pham, N. T., Respati, T., Fitriyana, S., Faller, E. M., Baldonado, A. M., Billah, M. A., Aung, Y., Hassan, S. M., … Yi, S. (2022). Perceived COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness, acceptance, and drivers of vaccination decision-making among the general adult population: A global survey of 20 countries. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 16(1), e0010103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010103.

Meppelink, C. S., Smit, E. G., Fransen, M. L., & Diviani, N. (2019). “I was right about vaccination”: Confirmation bias and health literacy in online health information seeking. Journal of Health Communication, 24(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2019.1583701.

Morgan, P. D., Tyler, I. D., & Fogel, J. (2008, November). Fatalism revisited. In Seminars in oncology nursing (Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 237–245). WB Saunders.

Mosca, L., Mochari, H., Christian, A., Berra, K., Taubert, K., Mills, T., et al. (2006). National study of women’s awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation, 113, 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588103.

NCDHHS. (2022, February 24). NCDHHS makes key COVID-19 vaccine information available in N.C.’s most used languages. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2022/02/24/ncdhhs-makes-key-covid-19-vaccine-information-available-ncs-most-used-languages.

Neumann-Böhme, S., Varghese, N. E., Sabat, I., Barros, P. P., Brouwer, W., van Exel, J., ... & Stargardt, T. (2020). Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economic: HEPAC: Health Economics in Prevention and Care, 21(7), 977–982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6.

Niederdeppe, J., & Levy, A. G. (2007). Fatalistic beliefs about cancer prevention and three prevention behaviors. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 16(5), 998–1003. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0608.

Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill, L., Artiga, S., Alam, R., & Parker, N. (2021). Latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations race/ethnicity. Kais Family Found. Accessed September 4, 2022, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity/.

Ohlsen, E. C., Yankey, D., Pezzi, C., Kriss, J. L., Lu, P. J., Hung, M. C., Dionicio Bernabe, M. I., Kumar, G. S., Jentes, E., Elam-Evans, L. D., Jackson, H., Black, C. L., Singleton, J. A., Ladva, C. N., Abad, N., & Lainz, A. R. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination coverage, intentions, attitudes and barriers by race/ethnicity, language of interview, and nativity, National Immunization Survey Adult COVID Module, April 22, 2021–January 29, 2022. Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciac508. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac508.

Park, T. V., Dougan, M., Meyer, O., Nam, B., Tzuang, M., Park, L., Vuong, Q., & Tsoh, J. (2021). Differences in COVID-19 vaccine concerns among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: The compass survey. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01037-0.

Paul, E., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Predictors of uncertainty and unwillingness to receive the COVID-19 booster vaccine: An observational study of 22,139 fully vaccinated adults in the UK. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe, 14, 100317.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100317.

Paul, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2021). Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe, 1, Article 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.

Paz, M. I., Marino-Nunez, D., Arora, V. M., & Baig, A. A. (2022). Spanish language access to COVID-19 vaccination information and registration in the 10 most populous cities in the USA. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07325-z.

Persaud, C. (2021, April 5). Immigrant communities in PBC less likely to be vaccinated. Palm Beach Post. https://www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/local/2021/04/05/covid-few-seniors-vaccinated-palm-beach-county-immigrant-areas/4822129001/.

Pradhan, R. (2021, March 23). ‘Press 1 for English’: Vaccination sign-ups prove daunting for speakers of other languages. California Healthline. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://californiahealthline.org/news/article/press-1-for-english-vaccination-sign-ups-prove-daunting-for-speakers-of-other-languages/.

Richardson, A., Allen, J. A., Xiao, H., & Vallone, D. (2012). Effects of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on health information-seeking, confidence, and trust. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(4), 1477–1493. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0181.

Robertson, E., Reeve, K. S., Niedzwiedz, C. L., Moore, J., Blake, M., Green, M., Srinivasa, V. K., & Benzeval, M. J. (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the U.K. household longitudinal study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 94, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008.

Ross, J., Diaz, C. M., & Starrels, J. L. (2020). The disproportionate burden of COVID-19 for immigrants in the Bronx, New York. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(8), 1043–1044.

Saied, S. M., Saied, E. M., Kabbash, I. A., & Abdo, S. A. E. F. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy: Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID‐19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. Journal of Medical Virology, 93(7), 4280–4291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26910.

Salmon, D. A., Moulton, L. H., Omer, S. B., DeHart, M. P., Stokley, S., & Halsey, N. A. (2005). Factors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: A case-control study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(5), 470–476. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.5.470.

Sherman, S. M., Smith, L. E., Sim, J., Amlôt, R., Cutts, M., Dasch, H., Rubin, G. J., & Sevdalis, N. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 17(6), 1612–1621. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1846397.

Silva, C. (2021, February 22). “It’s life and death”: Non-English speakers struggle to get COVID-19 vaccine across US. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/02/22/covid-19-vaccine-registration-non-english-speakers-left-behind/4503655001/.

Sobo, E. J. (2015). Social cultivation of vaccine refusal and delay among Waldorf (Steiner) school parents. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 29(3), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12214.

Street, R. L. Jr. (2003).Communicating in medical encounters: An ecological perspective. In T. L. Thomson, Dorsely, T. L., A.M., Miller, K. I., & Parrott, R. (Eds.), Handbook of health communication (pp. 63–89). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stadnick, N. A., Cain, K. L., Oswald, W., Watson, P., Ibarra, M., Lagoc, R., Ayers, L. O., Salgin, L., Broyles, S. L., Laurent, L. C., Pezzoli, K., & Rabin, B. (2022). Co-creating a theory of change to advance COVID-19 testing and vaccine uptake in underserved communities. Health Services Research, 57(Suppl 1), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13910.