Abstract

Population-based screening programs invite otherwise healthy people who are not experiencing any symptoms to be screened for cancer. In the case of breast cancer, mammography screening programs are not intended for higher risk groups, such as women with family history of breast cancer or carriers of specific gene mutations, as these women would receive diagnostic mammograms. In the case of prostate cancer, there are no population-based screening programs available, but considerable access and use of opportunistic testing. Opportunistic testing refers to physicians routinely ordering a PSA test or men requesting it at time of annual appointments. Conversations between patients and their physicians about the benefits and harms of screening/testing are strongly encouraged to support shared decision-making. There are several issues that make this risk scenario contentious: cancer carries a cultural dimension as a ‘dread disease’; population-based screening programs focus on recommendations based on aggregated evidence, which may not align with individual physician and patient values and preferences; mantras that ‘early detection is your best protection’ make public acceptance of shifting guidelines based on periodic reviews of scientific evidence challenging; and while shared decision-making between physicians and patients is strongly encouraged, meaningfully achieving this in practice is difficult. Cross-cutting these tensions is a fundamental question about what role the public ought to play in cancer screening policy.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In any health system, policies and guidelines are necessary to ensure that scarce resources are managed optimally and in ways that reflect the best available evidence at the time. On the macro level, policies are often implemented on a system-wide basis, such as the case with mammography screening in Canada, where each province evaluates recommendations based on existing population-based evidence and sets their respective policy accordingly. On the micro level, policies are interpreted and implemented during the doctor-patient clinical encounter. Often, decisions are made in clinical contexts that contradict existing recommendations and policy. For example, a patient may insist on tests in the absence of clinically relevant symptoms, or a doctor may prescribe an otherwise unnecessary test simply because it has become part of their routine practice, as is the case of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test for men. In such cases, applying population-based guidelines at an individual level becomes challenging. We examine factors that can create tensions between these macro and micro levels, obstacles that can preclude their practical harmonization, and strategies promoted to bridge the divide—particularly shared decision-making within contexts of low democratization of risk. The contexts of this case study are mammography screening for breast cancer among women and PSA testing for prostate cancer among men. We draw insights from key informant interviews with policymakers responsible for screening programs in different jurisdictions in Canada as they discuss the challenges they face implementing population-based guidelines in clinical settings.

Background: Population-Based Cancer Screening Programs

A formalized population-based cancer screening program systematically invites otherwise asymptomatic people for testing. The program acts as a dragnet to identify undetected cancer before symptoms appear in order to treat it in its earliest phases of development and thereby prevent or delay its advancement (Morrison 1985). Screening should be clearly distinguished from cases where a doctor makes a clinical recommendation to order a diagnostic test for a patient that is presenting with symptoms or known risk factors. It should also be distinguished from opportunistic requests for a diagnostic test by a patient where no prior indication for it exists. With respect to our two cases in this chapter, mammography screening is a formally supported population-based program whereas PSA testing is not.

Uncertainty and Issues in Mammography Screening and PSA Testing

Mammography remains the standard clinical intervention to detect breast cancer in women and is the basis of existing screening programs. However, debates and uncertainty over mammography’s utility in cancer detection persist. The efficacy of mammography screening (in terms of identifying incidence and mortality rates) often lacks consistency in study design and rigor, which can lead to uncertainty (Autier and Boniol 2018; Printz 2014). One study may conclude that mammography generally reduces mortality rates (Hirsch and Lyman 2011), while another may argue that there has been relatively little mortality benefit (Autier and Boniol 2018). Some argue that the risks of mammography screening, such as overdiagnosis or overtreatment, do not outweigh the benefits of detecting cancer and potentially saving younger women’s lives (American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists 2011). Overdiagnosis refers to diagnoses of conditions that may never have caused symptoms or death and overtreatment refers to treatment for conditions that if left untreated, were unlikely to cause symptoms or death (Bhatt and Klotz 2016). The debates can even pit medical disciplines against each other, with radiologists more commonly promoting mammography efficacy—especially for younger women, who may develop more aggressive cancers—against epidemiologists who may exhibit more caution toward mammography when interpreting trial results or retrospective analyses of data from screening programs in light of risks (Miller et al. 2014; Layne 2016; Ray et al. 2017). Diverse specialties may look at the same studies where the evidence seems clear, but weigh the evidence differently in their interpretations based on their underlying values. This has led to uncertainty in whether mammography screening is ultimately beneficial for women under 50 years of age (Autier and Boniol 2018).

Similar issues bedevil the use of the PSA test to detect prostate cancer. While the PSA test has been shown to assist in detecting potential prostate cancer and evaluating treatment strategies, its indications, the evidence, and its risk have provoked debate as to its own effectiveness as a potential screening tool. A high PSA score can be caused by numerous benign factors and prostate cancer can be present without a high PSA score (Obort et al. 2013). Such an unclear continuum of risk along the spectrum of PSA scores can lead to high rates of false-positives, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment. Reviews of studies have had contradictory results as to its efficacy as a means of testing for prostate cancer and whether such harms outweigh the relative reduction in cancer mortality (Croswell et al. 2011). The overall uncertainty as to the value of the PSA test has meant that there is no formalized prostate cancer screening program (Law et al. 2020).

Population-Based Health Policy Recommendations for Prostate and Breast Cancers in Canada

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) entrusts the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) with developing clinical guidelines and recommendations (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care 2019). The CTFPHC utilizes methods of evidence-based medicine wherein they conduct systematic reviews of clinical research in an effort to arrive at a consensus on which to base recommendations for patient management and care. Although these guidelines are intended to assist decision-making between doctors and individual patients, recommendations are largely drawn from population-level data. While population-based research has long since become a cornerstone in guiding evidence-based clinical practice, it has also provoked critique (Trinder and Reynolds 2000). Most notably, generalized conclusions at the population level can be difficult to translate into the individualized level of clinical practice, especially when these prove irreconcilable with the values of patients and doctors. Also, it has prompted accusations of promoting the rationing of health care (Kelly and Cronin 2011). Consequently, doctors may sometimes receive instructions to view practice recommendations not as templates of care for all patients, but as one factor among others to consider when making a decision on preventive care (Hoffman and Nguyen 2011).

The CTFPHC’s current recommendations about prostate and breast cancer screening were published in 2014 and 2011, respectively. In each case, the CTFPHC concluded that relatively small reductions in prostate and breast cancer (for younger women) mortality resulting from screening were eclipsed by substantial harms, including false-positive test results, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment (Dunfield et al. 2014; Fitzpatrick-Lewis et al. 2011). The CTFPHC reaffirmed a recommendation held since 1994 that the PSA test should not be used to screen asymptomatic men of any age for prostate cancer (Bell et al. 2014), and recommended against routine mammograms to screen for breast cancer for average risk women aged 40 to 49 years (The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care 2019). In 2018, as part of an updated review of the evidence, the CTFPHC reaffirmed these recommendations for mammography screening (Klarenbach et al. 2018).

Provincial/Territorial Implementation of PSA Testing and Mammography Screening Programs

While the CTFPHC makes screening recommendations, it is the policymakers who are left to implement policies for their jurisdictions. Across Canada, there has been no formalized screening program for prostate cancer using the PSA test. Despite this, high rates of unorganized, opportunistic PSA testing remain in Canada even in the absence of formalized screening programs (Beaulac et al. 2006; Canadian Cancer Society's Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics 2012). This means that although many asymptomatic men are being tested for prostate cancer, they are being exposed to potentially unnecessary harm. There is also variability over whether PSA testing is an insured health service across Canada. In some provinces (such as Manitoba), the cost of a PSA test is covered as a publicly financed health service, while in others (such as Ontario), the patient must bear the cost of the test (approximately $30–50)Footnote 1 if the test is not ordered because of a clinical suspicion of prostate cancer (Ontario Government 2021). In Canada, which has a publicly funded health system, this variability in funding may reflect uncertainty around the value of the test.

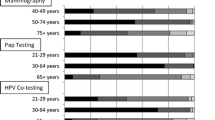

For breast cancer, all Canadian provinces and territories (aside from Nunavut) have screening programs (as a fully insured health service) that include women aged 50–69. There is considerable variation between provinces for their practice guidelines for women under 50. Some begin at age 40 (such as Prince Edward Island), others permit self-referral of women 40–49 years old (such as British Columbia), and most remaining provinces (such as Alberta) only permit screening of women aged 40–49 if deemed high risk or have a physician referral (Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, 2021/2022). These current practice guidelines have undergone subtle shifts over the past several years and are also likely to continue evolving in the future (Canadian Partnership Against Cancer 2012). While the CTFPHC’s recommendation is intended to prevent excessive harms due to false positives and overdiagnosis, the rates of false positives in Canada have been shown to be excessive, with younger women having a higher frequency than older women (Le et al. 2016).

The dissonance between recommendations and practice in prostate cancer screening, as well as the provincial variations in policy for breast cancer screening, demonstrate how the uncertainties of mammography screening and PSA testing efficacy can filter their way from the existing evidence, to policy recommendations, and down to clinical practice. In the clinical setting, these uncertainties may also be further complicated by people’s political, economic, cultural, and personal values (all of which can inform the subjective weighting of risks versus benefits) or the practicalities of the clinical encounter (Atkins et al. 2005). Doctors may tend to rely more on their individual judgments and diagnostic routines (Goldman and Shih 2011), or patients may insist on asymptomatic testing and overestimate the benefits of mammography screening and PSA testing (Volk et al. 2003; Woloshin et al. 2000). To bridge the divide, Shared Decision-Making (SDM) has been promoted as a strategy that can be sensitive both to the nuances of the evidence (and perhaps reduce unnecessary testing) and the values of patients and doctors (who may be more inclined to test).

The Shared Decision-Making (SDM) Model

The shared decision-making (SDM) model has been lauded as a more equitable and empowering approach for guiding doctor-patient decision-making (Elwyn et al. 2012). SDM entails three stages: information exchange between the doctor and the patient about benefits and risks of a strategy or intervention as determined by existing evidence (generally initiated by the doctor) as well as the patient’s values and preferences (generally solicited from the patient); deliberation on the options available; and finally the decision—with the ultimate decision being ideally consensus-based (Charles et al. 1997, 1999). SDM ideally leverages more egalitarian power distribution between patients and doctors (Goodyear-Smith and Buetow 2001), as well as fosters trust that most patients have in their healthcare provider (HCP) as an information source (Chawla and Arora 2013; Ipsos Reid 2012; Kraetschmer et al. 2004, Thom et al. 2004).

In situations where treatment or diagnostic options are clear, SDM may not be the most suitable approach for clinical decision-making (Schrager et al. 2017). However, when there may be more than one equally valid option based on available evidence and interpretations, SDM may be the best way for doctors and patients to discuss and weigh options that allow for the consideration of patient values and preferences. In this vein, SDM seems well-suited to discussions about mammography screening and PSA testing between doctors and their patients. The ambiguous nature of the evidence implores a discussion about risks and benefits of the tests, as well as cultural values, preferences, and beliefs with calls for greater use of SDM in cancer screening decisions for several years (Stefanek 2011). In fact, the CTFPHC guidelines for PSA testing (2014) and mammography (2011 and the 2018 update) specifically state that despite their recommendations against screening for specific populations, doctors should still actively discuss risks and benefits and facilitate decisions that respect the values and preferences of their patients.

Patient preference must be considered in the decision-making practice. Here too a spectrum exists: some patients want more autonomous control over decisions, others prefer to more passively leave decision-making to their doctor, compared to those who may want a blended collaborative role (Flynn et al. 2006; Levinson et al. 2005; Nies et al. 2017). Despite the heterogeneity in patient preferences, ostensibly SDM should be amenable to these kinds of individualized factors, and allow whatever preferences that exist to have their place in any decision-making process about screening (Elwyn et al. 2016). However, a number of studies on cancer screening decision-making have shown that SDM has not been well incorporated into practice (DuBenske et al. 2018; Feng et al. 2013; Katz et al. 2012; Hoffman et al. 2014).

Doctors may also have their own unique practices and preferences that can vary between individuals. This can be a barrier to SDM in terms of the application of best practice guidelines as well as informed decision-making. Physicians may be more likely to screen or test in excess of recommendations for a variety of reasons: they may defer to patient concerns/demands, disagree with guidelines, worry about missing potential cancer, or lack time to discuss risks and benefits (Haas et al. 2016). In addition, values around potential cost savings for the healthcare system versus individual rights to health care may play into decision-making practices. Preferences or constraints along these lines can lead to outcomes where people who may not necessarily require screening or testing receive it anyway (satisfying the desires of patients or doctors), which may not line up with clinical recommendations (Driedger et al. 2017).

SDM continues to be promoted as the preferred approach to making clinical decisions about cancer screening (Hoover et al. 2018; Lang et al 2018; Schrager et al 2017). We are currently left with a dilemma of how to reconcile evidence-based recommendations with the imperatives of SDM. On the one hand, prevailing guidelines posit that rates of mammography screening and PSA testing should be reduced to prevent unnecessary treatments. On the other hand, SDM promotes an understanding of risks and benefits, but it also invites individual preferences to inform the decision, which may be a demand for a test that could be unnecessary.

Methods: Key Informant Interviews with Senior-Level Policymakers

Senior-level policymakers (n = 12) were identified by members of the research team through purposive and snowball sampling and were located at provincial/territorial cancer agencies (n = 6), ministries of health in provinces/territories (n = 3), at national cancer advocacy organizations (n = 2) and expert panels/organizations that publish clinical guidelines (n = 1).

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (Reference number: H2010: 194). Following informed consent protocols, face-to-face and telephone interviews with persons responsible for cancer screening policy across CanadaFootnote 2 were conducted between November 2012 and March 2014. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, verified for accuracy, and imported into NVivo9™. Detailed codebooks were established following an iterative process of reviewing transcript excerpts for all datasets and developing coding schemes following standard protocols (Richards 2014). After coding data, we identified key themes in the data using the constant comparative and concept-development approach (Strauss and Corbin 1998), searched for contradictory or contrasting perspectives, and used triangulation to identify areas of agreement/disagreement across the dataset. In the results presented below, selected quotes are included to represent key themes identified throughout the dataset and policymakers’ names and positions are excluded to protect anonymity.

Results

Key informants shared a number of inter-related factors about the evolving nature of PSA testing and mammography screening, SDM and doctor-patient interaction, and potential influence for the integration of CTFPHC recommendations into clinical practice and policy. First, there has been shifting conceptions of the efficacy of mammography and PSA that being tested early and often is always beneficial. Second, participants described a shift that has occurred within the dynamics of clinical decision-making, with greater emphasis now being given to informed decision-making and patient autonomy. Third, these shifting paradigms underlying breast cancer screening and PSA testing require good science communication practice and health literacy skills. However, patients and doctors may be on differing levels of readiness to discuss new evidence and create space to allow for greater patient autonomy in informed decision-making. Fourth, individual patients can bring varying values and preferences that will influence their interpretation of evidence. Lastly, key informants frequently noted that doctors themselves may be one of the crucial obstacles that limit better integration of recommendations into practice.

Challenges in Shifting Entrenched Attitudes Among Different Stakeholders

Some of the participants asserted that for the past decades there had been a general consensus—even wholehearted enthusiasm—among the public, front-line medical staff, and policymakers as well, that asymptomatic screening and testing for cancers is generally a good thing to do. One key informant noted that the assumption that early screening or testing was always beneficial became a default “common sense” position. Any attempts to lower the rates of uptake for screening or testing could then easily be mischaracterized as being inherently wrong, biased in some way, or could leave health systems or doctors vulnerable to accusations that they are putting people’s lives at risk just to save some money. When describing the massive exponential growth of PSA testing in their province over the previous decades, another key informant indicated that high rates of opportunistic testing had become so accepted that it had become “entrenched” and “out of control.”

So the clinicians writing up the requests for [tests], also the population, and the staff from the public health departments who have to administer these things … they have the gung-ho attitude of let’s do annual everything, screening everything, and if people are entitled to annual screening then cutting back must be a bad thing and we can’t be seen to be cutting back for the sake of money.

Shifts to Individualized “Informed” Decision-Making and Communicating Risks and Benefits

Key informants held that clinical practice was not only shifting away from a default promotion of asymptomatic screening/testing, but also from paternalist dynamics of the doctor-patient encounter—where the doctor was expected to prescribe an intervention and the patient complies. Most agreed that these encounters are moving toward a model of shared (or ‘informed’—the term that key informants used most often) decision-making.

To whatever degree that the science is able to describe the benefits and risks [of screening], the decision-maker increasingly must be the individual [patient].

While most key informants agreed that individualized informed decision-making is the direction that practice is heading, many also maintained that this transition in clinical culture creates particular challenges. The overarching tension is that policymakers make decisions whether or not to set up screening programs based on population-based data, but that decisions about whether to screen or test for breast or prostate cancer are carried out at an individual patient-specific level. Reconciling the individual from the aggregate is fundamentally challenging because perceptions about patient benefits at the individual level may not be well aligned with population best-practice recommendations.

This is sort of public health and a population approach to screening versus the individual. And we’re [policymakers] not about the individual and that’s often what the clinicians are focused on. We’re talking about what’s of benefit to a whole population target group [not the individual].

A challenge identified by many participants is that informed decision-making relies on the ability of doctors to adequately communicate health information and improve health literacy related to individual as well as population-based evidence. Most key informants agree that getting the messaging across is not simple or easy. Both patients and doctors may be new to discussions around decision-making and may struggle with either giving or receiving population-based risk/benefit information.

I think that trying to communicate and talk about population level data and how that applies to the individual, I think that’s quite new for patients and physicians too. It’s a shift from how we used to function, and I think providers and patients are at different levels of readiness for that kind of role … to move to an informed decision-making model, it’s not that easy.

Key informants commonly noted that part of the challenge of communicating risk/benefit information is that the concepts conveyed may be confusing, and communicating the relative probabilities also means that the notion of uncertainty is very much part of the equation.

We’ve moved from that sort of position of screening is always a good thing, to really then having to communicate the balance of benefit and harm. And how do you communicate uncertainty? Like, how do we get an individual to understand a number needed to screen to save a life, or what’s the risk of overdiagnosis? Trying to make those concepts understandable to the public is a huge challenge.

Some key informants noted that patients may or may not even want that kind of information depending on the value that they assign it. Additionally, the evidence itself can be difficult to put into language that the lay public can understand and use to support their decision-making. The doctor-patient interaction is the assumed natural environment for having these conversations, but there may also be a need for a broader multi-sectoral push to communicate these concepts to the public in order to build up a more nuanced culture of understanding for uncertainty in evidence and policy.

I think on the public side, at least as far as PSA goes, I don’t think [educating] will be that bad. Because I think if you say to men, ‘if you don’t have any symptoms and you’re under 50 you don’t need this test,’ they’ll be okay with that. Because a lot of them, like I say, probably don’t even know they’re getting it anyway. But how do you educate an entire population? That’s not easy. So we’re going to have multiple avenues for public education, whether it’s through media campaigns, one-on-one consultations, and mail outs, plus the physician piece. You’ve got to come at them from all angles.

On the other hand, some patients may prefer that the decision-making role should rest primarily with the doctor, and are more willing to eschew discussions of evidence and support whatever option their doctor proposes.

Communicating Patient Values and Preferences

While imparting information about screening and testing risks and benefits can be a challenging and novel task for doctors, policymakers acknowledged that each patient navigates their situation according to their own values, preferences, and priorities. For informed decision-making, the doctor needs to solicit this information from their patient and then balance it with communicating information about the risks and benefits of screening or testing in order to best support shared decision-making.

The evidence [for cancer screening] may have the magnitude of benefits and people put different weights on the risks of the procedure. So that information may be there, but the value you put around the benefits or the risks may be different. And so it’s not just a number kind of assessment, you know, a bigger number is better or a lower number is better. There is the human value that you attach to it, ‘Does that matter to me?’

Other key informants agreed that a process of active information and values exchange was necessary to arrive at the optimal decision that balances fidelity to both prevailing recommendations as well as patient values. There are, as one participant noted, instances when the ‘right’ decision (as perceived by the patient—or the doctor for that matter) is not going to line up with existing recommendations given a particular patient’s values and preferences. But, when good communication is practiced, the odds are increased that a doctor can be sensitive to patient values and that the evidence underpinning recommendations is understood and considered by the patient as well. Regardless of the decision, the important component is to preserve trust, amicability, and open communication between the doctor and patient.

We don’t even have a systematic approach to engage the public and individuals. Someone could be helped in the decision about getting a mammogram by just somebody who understands what their issues are. You know, so that a doctor who realizes the biggest issue for a woman is fear of breast cancer. It is such a big issue that she can’t sleep at night because her aunt died of breast cancer. She should be screened if that’s what she wants, but she should be told that there’s risks of screening. We might get it wrong. You might have an unnecessary biopsy. And she says, ‘I don’t care, you can do 10 biopsies, I want to go to sleep at night knowing that the chance of me having cancer is as low as it can be. She should get screened. It’ll save our health system millions of dollars in prescription drugs. You could look at it any way you want. And the person who says if I have breast cancer, that’s God’s way of telling me it’s time to visit Him, I’ll get it when I get it, I don’t want to know until I have to. That person should not be screened. Ever. So, we’re out of date in how we approach this stuff, but that’s complicated. And governments hate complexity. They hate individual judgment—it’s all got to be reduced to a one line sound bite. [It] drives me nuts.

Physician Practice, the Challenge of Change and Needing to Change the Path

Supporting shared decision-making practices often falls to doctors to implement better communication around health decision-making options. The rationale for shifting responsibility from the healthcare system and policymakers to doctors was raised by many of our key informants. Key informants regularly pointed to the catch-22 of implementing SDM. They discussed the need for personalized practice as doctors, established norms around screening acceptability, and the very real constraints of appointment length as barriers to soliciting patient preferences and improving health literacy around the benefits and harms of screening and/or testing. One key informant summed up many of these challenges.

[PSA testing’s] got the highest participation rate. And it’s the program that’s basically not recommended. So it’s just bizarre. And when the clinical trials come out and showed that there really wasn’t much benefit to PSA testing, okay you would hope that the physicians would take that and adjust their practice. But that’s the other challenge, physicians’ practice behavior. Oh boy, getting them to change is always really difficult. A lot of physicians will say, ‘I found prostate cancer in some of these guys and the guy was asymptomatic. If I hadn’t done this that might have been the one that would have been more aggressive. So isn’t it easier for me to just test them all and not worry about it? Versus trying to be selective about who I should test?’ We have programmed our population that breast screening, that finding cancer early is good, right? That just makes sense, doesn’t it? It’s pretty hard now to go out to the public and say, ‘Well that doesn’t really apply to prostate cancer. Finding it early might not make a difference.’ It’s a contradictory message … I fully understand the General Practitioner in his or her position like, ‘I don’t have time to explain all this stuff to people and I know that we do find these cancers.’ So that’s where we’re at.

Likewise, a few policymakers described the need to develop relatively conservative strategies for dealing with uncertainty about screening, such as needing to cultivate the support of physician groups before attempting to implement a new policy. By contrast, one cancer agency was contemplating a more disruptive response for change. In some provinces, the PSA test is included in the checklist of routine lab requisition forms. This one cancer agency was considering having the test removed from the routine forms, and implementing a different form specifically for the PSA test to stimulate physicians and patients to devote greater consideration before ordering the test for screening purposes. Instead of changing the mindset of physicians, that cancer agency wanted to change the pathway for how requisitions were ordered:

Part of the problem with the PSA test is that it's too easy—it’s just another check box on your lab blood requisition form. We want to have PSA taken off the form so that a physician would have to have a discussion with the patient about the test. A lot of guys are having a PSA test and they don’t even know it, because the doctor takes blood and checks off cholesterol and this and that, and the guy doesn’t know everything that's being checked.

Discussion

While numerous other studies have focused on the roles that doctors and patients play in making decisions about cancer screening, the perspectives of policymakers shed fresh light on those responsible for interpreting emerging evidence and recommendations and implementing guidelines for clinical practice. Upstream interventions that use population-based evidence and a systems perspective to determine efficacy and feasibility influencing downstream outcomes are central to the democratization of risk. SDM is essential at the micro level to unpack what constitutes an informed decision when faced with scenarios where uncertainty is central to the situation.

Some participants may have perceived SDM to be more embedded in practice than it is due to generalized discourses around the need for SDM and patient-centered care, rather than as a change that is still very much required and in its infancy. Many stakeholders may be new to SDM and there may be challenges involved in shifting values and preferences in a meaningful way toward a conversation that focuses on ensuring people comprehend risks and benefits. The assumption that SDM and its egalitarian emphasis was ‘the norm’ in screening decisions may reflect tensions between the macro level where policymakers reside and the micro level where clinician and patients interact. An additional clue that some mischaracterization of SDM dynamics existed in the comments of key informants was their common use of the term ‘informed’ decision-making, rather than ‘shared.’ Although their description of the shifts that were occurring were apt to capture the dynamics of SDM (e.g., a bi-directional flow of information between doctors and patients and collaborative decisions), ‘informed’ is not synonymous with ‘shared.’ ‘Informed’ decision-making is unidirectional with information flowing from the doctor and the patient making the decision (Schrager et al. 2017). True (and as participants noted) ‘shared’ and ‘informed’ decision-making places the patient in more of a decision-making role than paternalistic care, but participants’ use of ‘informed’ suggests that there may be lingering confusion on the policy level of what is being promoted or realized by SDM for breast and prostate cancer screening discussions. Key informants were keen to pinpoint the challenges involved in SDM’s potential application which mirrored challenges identified in existing literature. While at times patients might be happy to function within an informed decision-making context, there remains dissonance between policy and practice expectations. A lack of dialogue and reciprocal information exchange is a long-standing gap reported by patients about their discussions with doctors about cancer screening decisions (Hoffman et al. 2014; Katz et al. 2012). Yet patient preferences for cancer screening and testing are crucial in situations where uncertainty is present and patient-based considerations of risk/benefit trade-offs can be a key part of the decision-making equation (Gunn et al. 2021; Howard et al. 2015; Nguyen et al. 2021). This fact likely underpins the continued promotion of SDM in cancer screening decisions and the tensions between cultural values and stakeholder preferences.

Study participants identified a lack of risk/benefit information about mammography or PSA testing from doctors to their patients as a challenge to SDM adoption. Participants agreed that sharing population-based information about uncertainties and probabilities can be a difficult task, given the conflicts, subtleties, and nuances of the evidence (Bell et al. 2017; Keating and Pace 2018; Lang et al. 2018). Some participants believed that conveying risk/benefit and uncertainty information about testing or screening is something to which doctors may not yet be that accustomed. Doctors may avoid SDM conversations and ignore prevailing guidelines, especially if they have failed to previously catch cases of asymptomatic cancer or they simply lack the time for sharing risk/benefit information (Haas et al. 2016). A lack of discussion has consequences, as several studies have shown that men are less likely to opt for PSA testing if they are given the benefits and risks of testing and made aware of the existing uncertainties (Flood et al. 1996; Volk et al. 2003). Another study has also shown that if physicians are given a primer on PSA testing, during follow-up visits with men, there is increased likelihood for SDM and greater potential for reduced PSA testing (Feng et al. 2013).

Some participants identified a core challenge—or contradiction—of applying population-based evidence into the clinical encounter and were wholly aware of the limitations and strictures of their perspective as policymakers. From their point of view, they see population-level trends whereas physicians and patients are often looking downstream at individual-level outcomes. As we found, participants spent considerable time discussing the micro-dynamics of doctor-patient interaction—an unavoidable nod toward the bridge that population-based evidence must cross. This seeming dissonance between the macro and micro levels has indeed formed the basis of previous criticism of clinical guidelines based on population-level evidence (Trinder and Reynolds 2000). The natural extension of this dilemma is that (as noted above) even within the parameters of SDM—or especially so, given the prominence it accords to patient preference—there will be many instances where the decision that is made will not align with evidence-based recommendations. In many cases, the odds of unnecessary testing taking place can be reduced if the patient knows which way the evidence is leaning and can negotiate their own values in light of it (Klarenbach et al. 2018). Thus, for mammography and PSA testing, doctors need to also allow the time for values clarification (if a patient so desires) alongside providing the relevant evidence (despite its relative complexity). Our study findings support the continued call for doctors to better integrate SDM into their discussions with patients (Bell et al. 2017; Dasarathy and Rajesh 2020). If asymptomatic mammography screening and PSA testing is to be better negotiated with SDM—with its greater attentiveness to being preference-sensitive health care—perhaps some degree of what is considered unnecessary testing (by the standards of population-based evidence) will be unavoidable. Even if the decision does not align with existing recommendations, we can hope that the discussions around it were equitable and informed, the preferences of the parties were recognized, the potential for a decision that matches evidence-based guidelines was advanced, and that the relationship between decision-making parties was fostered.

While patients may require their own help in comprehending the evidence through a variety of means (i.e., public service announcements, advertising campaigns, clinical discussions), a valuable insight provided by some participants was that doctors themselves may also need some continuing education on the newer and nuanced styles of interpreting and communicating the “gray areas” of evidence for breast and prostate cancer screening. As we illustrate through our results, we may still be quite early on in our understanding of the paradigm shifts that have taken place and how those who are faced with responding to them may be struggling to do so.

Conclusion

This chapter focused on a real tension concerning public involvement in health risk decisions. At the macro risk governance level, there is little engagement with the public around population-based recommendations or how health systems implement national recommendations in their jurisdictions. At the micro doctor-patient level, there are several opportunities through SDM for individual values and preferences to influence decisions. This dual tension at the macro and micro level is not wholly inappropriate in a health system that must adhere to using public resources in an equitable and defensible manner. Policymaker participants provided a unique perspective on the challenges facing SDM adoption as well as tensions inherent in establishing clinical policy for diverse populations from the more lofty heights of the policy realm. Fundamentally, more research into when ‘less care’ is in fact ‘better care’ is needed not only about how to navigate these conversations at the micro level between the doctor and patient, but also at the systems level when making policies based on effective use of scarce resources to best serve the population.

Notes

- 1.

At the time of our study during focus group data collection (data not included here), men reported paying $30. Current lab rates list $35. https://www.lifelabs.com/test/prostate-specific-antigen-psa-test/

- 2.

Despite multiple attempts, no participants were recruited from the Maritimes.

References

American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. (2011). Practice bulletin no. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 118(2 Pt 1), 372–382.

Atkins, D., Siegel, J & Slutsky, J. (2005). Making policy when the evidence is in dispute. Health Affairs, 24(1), 102–113.

Autier, P. & Boniol, M. (2018). Mammography screening: A major issue in medicine. European Journal of Cancer, 90, 34–62.

Beaulac, J. A., Fry, N.R., & Onysko, J. (2006). Lifetime and recent prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening of men for prostate cancer in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 97(3), 171–176.

Bell, N., Connor, S., Gorber, A., Joffres, M., Singh, H., Dickinson, J., Shaw, E., Dunfield, L., & Tonelli, M. (2014). Recommendations on screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(16), 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.140703

Bell, N., Grad, R., Dickinson, J., Singh, H., Moore, A., Kasperavicius, D., & Kretschmer, K. (2017). Better decision making in preventive health screening: Balancing benefits and harms. Canadian Family Physician/Medecin de Famille Canadien, 63(7), 521–524.

Bhatt, J., & Klotz, L. (2016). Overtreatment in cancer—is it a problem? Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 17(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2016.1115481

Canadian Cancer Society's Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. (2012). Canadian cancer statistics 2012. Toronto, Canadian Cancer Society. Retrieved April 28, 2021, from https://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2012-EN.pdf?la=en#:~:text=An%20estimated%20186%2C400%20new%20cases%20of%20cancer%20and%2075%2C700%20cancer,48%25%20in%20women

Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. (2012). Breast control in Canada: A system performance focus report. Toronto, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer.

Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. (2021/2022). Breast Cancer Screening in Canada: 2021/2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022 from https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/breast-cancer-screening-in-canada-2021-2022/summary/

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. (2019). About Us. Retrieved January 13, 2021, from http://canadiantaskforce.ca/about/.

Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine, 44(5), 681–692.

Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1999). Decision-making in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Science and Medicine, 49(5), 651–661.

Chawla, N., & Arora, N. K. (2013). Why do some patients prefer to leave decisions up to the doctor: Lack of self-efficacy or a matter of trust? Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 7(4), 592–601.

Croswell, J. M., Kramer, B. S., & Crawford, E. D. (2011). Screening for prostate cancer with PSA testing: current status and future directions. Oncology (Williston Park), 25(6), 452–460, 463.

Dasarathy, J., & Rajesh, R. (2020). PSA cancer screening: a case for shared decision-making. Journal of Family Practice, 69(1), 26;28; 30;32; 46. PMID: 32017831.

Driedger, S. M., Annable, G., Turner, D., Brouwers, M., & Maier, R. (2017). Can you un-ring the bell? A qualitative study examination of the role of affect in cancer screening decision making. BMC Cancer, 17(647). DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3596-7.

DuBenske, L. L., Schrager, S. B., Hitchcock, M. E., Kane, A. K., Little, T. A., McDowell, H. E., & Burnside, E. S. (2018). Key elements of mammography shared decision-making: a scoping review of the literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(10):1805–1814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4576-6. Epub 2018 Jul 20. PMID: 30030738; PMCID: PMC6153221.

Dunfield, L., Usman, A., Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D., & Shane, A. (2014). Screening for prostate cancer with prostate specific antigen and treatment of early-stage or screen-detected prostate cancer: A systematic review of the clinical benefits and harms. Retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://canadiantaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014-prostate-cancer-systematic-review-en.pdf

Elwyn, G., Frosch, D., Thomson, R., Joseph-Williams, N., Lloyd, A., Kinnersley, P., Cording, E., Tomson, D., Dodd, C., Rollnick, S., Edwards, A., & Barry, M. (2012). Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), 1361–1367.

Elwyn, G., Frosch, D. L., & Kobrin, S. (2016). Implementing shared decision-making: consider all the consequences. Implementation Science, IS(11), 114–114.

Feng, B., Srinivasan, M., Hoffman, J. R., Rainwater, J. A., Griffin, E., Dragojevic, M., Day, F. C., & Wilkes, M. S. (2013). Physician communication regarding prostate cancer screening: Analysis of unannounced standardized patient visits. Annals of Family Medicine, 11(4), 315–323.

Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D., Hodgson, N., Ciliska, D., Pierson, L., Gauld, M., & Liu, Y. Y. (2011). Breast Cancer Screening. Hamilton, Ontario, McMaster University.

Flood, A. B., Wennberg, J. E., Nease, Jr., R. F., Fowler, Jr., F. J., Ding, J., & Hynes, L.M. (1996). The importance of patient preference in the decision to screen for prostate cancer. Prostate patient outcomes research team. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1(6),342–349.

Flynn, K. E., Smith, M. A., & Vanness, D. (2006). A typology of preferences for participation in healthcare decision making. Social Science and Medicine, 63(5), 1158–1169.

Goldman, J. J., & Shih, T. L. (2011). The limitations of evidence-based medicine--applying population-based recommendations to individual patients. Virtual Mentor, 13(1), 26–30.

Goodyear-Smith, F., & Buetow, S. (2001). Power issues in the doctor-patient relationship. Health Care Analysis, 9(4), 449–462.

Gunn, C. M., Maschke, A., Paasche-Orlow, M. K., Kressin, N. R., Schonberg, M. A., & Battaglia, T. A. (2021). Engaging women with limited health literacy in mammography decision-making: Perspectives of patients and primary care providers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(4),938–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06213-2. Epub 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 32935318; PMCID: PMC8042081.

Haas, J. S., Sprague, B. L., Klabunde, C. N., Tosteson, A, N., Chen, J. S., Bitton, A., Beaber, E. F., Onega, T., Kim, J. J., MacLean, C. D., Harris, K., Yamartino, P., Howe, K., Pearson, L., Feldman, S., Brawarsky, P., & Schapira, M. M. (2016). Provider attitudes and screening practices following changes in breast and cervical cancer screening guidelines. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(1), 52–59.

Hirsch, B. R., & Lyman, G. H. (2011). Breast cancer screening with mammography. Current Oncology Report, 13(1), 63–70.

Hoffman, K. E., & Nguyen, P. L. (2011). The debate over prostate cancer screening guidelines. Virtual Mentor, 13(1), 10–15.

Hoffman, R. M., Elmore, J. G., Fairfield, K. M., Gerstein, B. S., Levin, C. A., & Pignone, M. P. (2014). Lack of shared decision making in cancer screening discussions: results from a national survey. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 47(3), 251–259.

Hoover, D. S., Pappadis, M. R., Housten, A. J., Krishnan, S., Weller, S. C., Giordano, S. H., Bevers, T. B., Goodwin, J. S., & Volk, R. J. (2018). Preferences for communicating about breast cancer screening among racially/ethnically diverse older women. Health Communication, 1–5.

Howard, K., Salkeld, G. P. Patel, M. I., Mann, G. J., & Pignone, M. P. (2015). Men's preferences and trade-offs for prostate cancer screening: A discrete choice experiment. Health Expectations, 18(6), 3123–3135.

Ipsos Reid. (2012). Life-savers, medical professionals top the list of most trusted professionals. Toronto, Ipsos Reid.

Katz, M. L., Broder-Oldach, B., Fisher, J. L., King, J., Eubanks, K., Fleming, K., & Paskett, E. D. (2012). Patient-provider discussions about colorectal cancer screening: who initiates elements of informed decision making? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(9), 1135–1141.

Keating, N. L. & Pace, L. E. (2018). Breast cancer screening in 2018: Time for shared decision making. Journal of the American Medical Association, 319(17), 1814–1815.

Kelly, A. M. & Cronin, P. (2011). Rationing and health care reform: Not a question of if, but when. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 8(12), 830–837.

Klarenbach, S., Sims-Jones, N., Lewin, G., Singh, H., Thériault, G., Tonelli, M., Doull, M., Courage, S., Garcia, A. J., & Thombs, B. D. (2018). Recommendations on screening for breast cancer in women aged 40–74 years who are not at increased risk for breast cancer. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(49), E1441.

Kraetschmer, N., Sharpe, N., Urowitz, S., & Deber, R. B. (2004). How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision-making? Health Expectations, 7(4), 317–326.

Lang, E., Bell, N. R., Dickinson, J. A., Grad, R., Kasperavicius, D., Moore, A. E., Singh, H., Theriault, G., Wilson, B. J., & Stacey, D. (2018). Eliciting patient values and preferences to inform shared decision making in preventive screening. Canadian Family Physician, 64(1), 28–31.

Layne, G. P. (2016). Screening mammography: Controversy and recommendations. West Virginia Medical Journal, 112(6), 26–29.

Law, K. W., Nguyen, D. D., Barkin, J., & Zorn, K. C., (2020). Diagnosis of prostate cancer: the implications and proper utilization of PSA and its variants; indications and use of MRI and biomarkers. Canadian Journal of Urology, 27(27 Suppl. 1), 3–10. PMID: 32101694.

Le, M. T., Mothersill, C. E., Seymour, C. B., & McNeill F. E. (2016, September). Is the false-positive rate in mammography in North America too high? British Journal of Radiology, 89(1065), 20160045.

Levinson, W., Kao, A., Kuby, A., & Thisted, R. A. (2005). Not all patients want to participate in decision making: A national study of public preferences. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(6), 531–535.

Miller, A. B., Wall, C., Baines, C.J., Sun, P., To, T., & Narod, S. A. (2014). Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: Randomised screening trial. British Medical Journal, 348, g366.

Morrison, A. (1985). Screening in Chronic Disease. New York, Oxford University Press.

Nies, Y. H., Islahudin, F., Chong, W. W., Abdullah, N., Ismail, F., Ahmad Bustamam, R. S., Wong, Y. F., Saladina, J. J., & Mohamed Shah, N. (2017). Treatment decision-making among breast cancer patients in Malaysia. Patient Prefer Adherence, 11, 1767–1777.

Nguyen, D. D., Trinh, Q. D., Cole, A. P., Kilbridge, K. L., Mahal B. A., Hayn, M., Hansen, M., Han, P. K. J., & Sammon, J. D. (2021). Impact of health literacy on shared decision making for prostate-specific antigen screening in the United States. Cancer, 27(2), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33239. Epub 2020 Nov 9. PMID: 33165954.

Obort, A. S., Ajadi, M. B., & Akinloye, O. (2013). Prostate-specific antigen: Any successor in sight? Reviews in Urology, 15(3), 97–107.

Ontario Government. (2021). Prostate cancer screening. Retrieved April 28, 2021 from https://www.ontario.ca/page/prostate-cancer-screening

Printz, C. (2014). Mammogram debate flares up: Latest breast cancer screening study fuels controversy. Cancer, 120(12), 1755–1756.

Ray, K. M., Joe, B. N., Freimanis, R. I., Sickles, E. A., & Hendrick, R. E. (2017). Screening mammography in women 40–49 years old: Current evidence. American Journal of Roentgenology, 210(2), 264–270.

Richards, L. (2014). Handling qualitative data (3rd ed.). Sage Publishing.

Schrager, S. B., Phillips, G., & Burnside, E. (2017). A simple approach to shared decision making in cancer screening. Family Practice Management, 24(3), 5–10.

Stefanek, M. E. (2011). Uninformed compliance or informed choice? A needed shift in our approach to cancer screening. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 103(24), 1821–1826.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications Inc.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. (2011). Recommendations on screening for breast cancer in average-risk women aged 40–74 years. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(17), 1991–2001.

Thom, D. H., Hall, M. A., & Pawlson, L. G. (2004). Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Affairs, 23(4), 124–132.

Trinder, L. & Reynolds, S. (Eds.). (2000). Evidence-based practice: A critical appraisal. Oxford.

Volk, R. J., Spann, S. J., Cass, A. R., & Hawley, S. T. (2003). Patient education for informed decision making about prostate cancer screening: A randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Annals of Family Medicine, 1(1), 22–28.

Woloshin, S., Schwartz, L. M., Byram, S. J., Sox, H. C., Fischhoff, B., & Welch, H. G. (2000). Women's understanding of the mammography screening debate. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(10), 1434–1440.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants for sharing their time, experiences, and insights regarding decision-making about breast and prostate cancer screening. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute held by author SMD entitled “Advancing quality in cancer control and cancer system performance in the face of uncertainty” (grant #700589). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Gary Annable (University of Manitoba), who was a full-time researcher with the project, and project co-lead, Dr. Melissa Browers (University of Ottawa), for their helpful comments on a much earlier draft of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Driedger, S.M., Cooper, E.J., Maier, R. (2023). Balancing Shared Decision-Making with Population-Based Recommendations: A Policy Perspective of PSA Testing and Mammography Screening. In: Gattinger, M. (eds) Democratizing Risk Governance. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24271-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24271-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-24270-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-24271-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)