Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic created economic turmoil and impacted various areas of life all over the world. One of the major socio-political aspects of this global crisis consisted of border closures and lockdowns imposed by governments. Migrant workers have been one of the most affected groups, because they are over-represented in vulnerable occupations and among workers with short-term labour contracts; hence, they are among the first to be laid off. Dependent for 30 years now on the financial capital coming from diverse types of migration – seasonal migration, circular mobility and remittances from international migration – the economy of Albania was negatively impacted by the consequences of these changes. Many migrant workers had to return to their country of origin and face the precarious situation from which they had already left. A lot of seasonal and circular migrant workers were trapped and could not emigrate. Outward mobility shrank or was postponed because of travel bans. The more significant consequences were experienced by seasonal migrants who are used to generating incomes through temporary work and who were unable to continue doing so due to being stuck in Albania. The fall in remittances during this period was partially caused by the strong impact that the crisis had on emigrant workers, be they temporary or permanent: the measures that prohibited many economic activities in the host countries; the difficulties of transferring money; as well as a significant portion of remittances normally making their way to Albania through informal channels.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic created economic turmoil and impacted various areas of life all over the world. One of the major socio-political aspects of this global crisis consisted of border closures and lockdowns imposed by governments. Migrant workers have been one of the most affected groups, because they are over-represented in vulnerable occupations and among workers with short-term labour contracts; hence, they are among the first to be laid off (Ullah et al., 2021). The loss of jobs and reductions in the wages of migrant and refugee workers as a result of the pandemic led to a decline in remittances globally of some USD$109 billion. Dependent for years now on the financial capital coming from diverse types of migration – seasonal migration, circular mobility and remittances from international migration – the economy of Albania was negatively impacted by the consequences of these changes (OECD, 2021). Many migrant workers had to return to their country of origin and face the precarious situation from which they had already left (Bartlett & Oruc, 2021). A lot of seasonal and circular migrant workers were trapped and could not emigrate. Outward mobility shrank or was postponed because of travel bans (Mara et al., 2022). The more significant consequences were experienced by seasonal migrants who are used to generating incomes through temporary work and who were unable to continue doing so due to being stuck in Albania. The labour market of Albania in 2020 faced a loss of 34,000 jobs and another increase of the unemployment rate (OECD, 2021). The fall in remittances during this period was partially caused by the strong impact that the crisis had on emigrant workers, be they temporary or permanent: the measures that prohibited many economic activities in the host countries; the difficulties of transferring money; as well as a significant portion of remittances normally making their way to Albania through informal channels (Barjaba, 2021; Topalli, 2021).

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic first struck Albania, as it did most of the rest of the world, in early 2020. To thwart the spread of the virus, Albania imposed a full lockdown during the first few months, which left the migrant population stranded. Faced with this new normality – high levels of unemployment, borders remaining closed and restrictions on travel and work – seasonal migrants sought other coping modalities. At the political level, the governments of the main Albanian migration destination countries – Italy, Greece and Germany – eased their border regulations to allow seasonal workers in during the coronavirus crisis, which created new possibilities for employment, especially in agriculture and healthcare (Augère-Granier, 2021). Some international organisations operating in Albania offered employment possibilities for vulnerable groups of returned migrants because of earlier rejections of their asylum requests. At the same time, intermediators found new channels to transport seasonal migrants and continue their operations informally.

All these efforts to ease the effects of the coronavirus pandemic were driven by the changes in the demands of the economy. The pandemic highlighted the role of ‘essential’ workers, many of whom are employed in less prestigious and poorly paid jobs, such as caring, transport, cleaning and check-out staff (Settersten et al., 2020). On the other hand, there was an increased demand for seasonal workers in agriculture and healthcare. In this chapter we explore the coping mechanisms which seasonal migrants adopted to navigate through the new normality created by the pandemic.

Seasonal migration trends in Albania during the pandemic followed the rules set by international border-crossing protocols. Dependent on these protocols, seasonal migrants departed for their destination countries or found other means of living in Albania in the short term. We find that, despite the restrictions, informal seasonal migration from Albania to Western countries continued during the pandemic. Seasonal migrants who could not get past the restrictions shifted their labour supply to other, easier-to-reach, destinations instead, such as Montenegro. Their adaption to the new normality turned out to be much quicker than regular seasonal-migration features would suggest. In this chapter, then, we aim to answer two main research questions:

-

1.

How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected migrants in Albania who are used to making a living out of seasonal migration?

-

2.

What have been the coping mechanisms that these migrants have chosen, or which they have been forced to choose, to adapt to the new situation?

2 Methodology

Our analysis draws on 60 in-depth semi-structured interviews with seasonal Albanian migrants who were in Albania at the time of the interview. Four in-depth interviews were conducted with key informants: with a regular seasonal migrant in Germany, a driver who manages a transport agency with Italy, a staff member of an intermediation employment agency and a representative from the Labour Office of the Shkodra region in northern Albania. The data were gathered between August and October 2020. The fieldwork was conducted in the Shkodra region. We gained access to Albanian seasonal migrants first through the main gatekeepers in the municipality of Shkodra, regional employment offices and international organisations which are focused on re-integration programmes addressing mainly vulnerable returnees. We also used the snowball technique to access and interview potential participants. All interviews were held in the Albanian language and selected quotes have been translated into English for this chapter. In what follows, interviewees are referred to by pseudonyms.

The interviews were transcribed preserving the original language, then coded, grouped in themes and analysed manually. The researchers assured all respondents that the information they gave would be used only for our academic research. Due to the decrease in the number of infections, we met the interviewees in person, in open-air settings and respecting social-distancing measures. The interviews typically lasted about 30 min, covering accounts of participants’ migration history and their recent situation due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The questions were organised as follows: first the interviewees were asked to give some general information on their family status and profession. We then asked questions about their migration path – their previous experiences, destination countries and reasons for migrating. For the third group of questions, we focused on migration during the pandemic, in particular on the different ways of migrating, their rationale of choosing the destination, their fears of getting infected and the measures undertaken to prevent it, the role of networks and the migrants’ strategies for adapting in the new normality.

Table 4.1 provides basic profile data on the participant sample. There were 50 men and 10 women with an average age of 45 years old. They worked mainly in Greece, Italy and Germany. One worked seasonally in the Netherlands and 10 in Montenegro. However, destination countries were not always the same, as some participants had worked in different European countries, depending on the job opportunities. The emigration route was generally undertaken by bus and the high season was from April to October. The main employment sectors in the destination country were construction, agriculture, services, cleaning, maintenance and factory work. For the most part migrants worked informally within the 3-month period for which they were allowed to reside in the destination country. The majority (65%) of the participants had an elementary education, 25% had completed secondary education and 11% had a university degree.

The main limitation of the study sample is the fact that all the participants were seasonal migrants who had remained in Albania following the pandemic outbreak. Another important group of informants would have been the seasonal migrants who stayed in the destination countries throughout the pandemic. This would have allowed us to obtain a more thorough perspective on seasonal migration from Albania.

3 Seasonal Migration from Albania Before and During the Pandemic

Seasonal migration from Albania to Western European countries has turned into a way of life for many Albanian individuals and families. Regarded as a phenomenon which benefits all the parties involved – the country of origin, the destination country and the migrants themselves – it has helped, on the one hand, to relieve the pressure of increasing unemployment rates in Albania and, on the other, to satisfy the demands for seasonal workers in many countries (Nicholson, 2004; Vadean & Piracha, 2009). According to Mai (2011), this ambivalent circulatory movement represents a choice by migrants to adapt to and benefit from the different opportunities – economic, social and political – provided by both the origin and the destination countries. Compared to other forms of migration (international, internal or return), seasonal and circular migration are the least explored due mainly to their irregular nature, despite having traditionally been strategies for living for many Albanians, especially after 1990 (Azzarri & Carletto, 2009; Çaro et al., 2014; Mai, 2011; Maroukis & Gemi, 2013; Nicholson, 2004). The main destination countries for seasonal migration were Greece, Italy and, recently, Germany. Geographical proximity, cultural closeness and social networks are the reasons shaping seasonal migration to Greece and Italy (Gemi, 2017). The economy of Greece depends heavily on the Albanian labour force which is used mainly by small and medium businesses (Gemi, 2017). Seasonal migration to Germany is nowadays based on the employment possibilities offered by different programmes or agencies operating in Albania, be they in healthcare, transport or services etc. Recently there has also been a growing number of countries, such as Malta, Sweden, France, the USA or the United Arab Emirates, employing seasonal migrants from Albania.Footnote 1 Unlike permanent migration, temporary migration was historically taken up by only one household member, mostly the male head of the house (Azzarri & Carletto, 2009). This trend has also changed recently due to the increase in the number of women working in the healthcare, elderly care or domestic and cleaning sectors. The governments of the main destination countries for seasonal migration – Greece and Italy – have signed agreements with the Albanian government for the seasonal employment of migrants.Footnote 2 International organisations also operate with programmes that assist the seasonal employment of Albanians in these countries. However, the number of seasonal migrants who circulate through formal avenues pales in comparison to the broader panorama of seasonal migration from Albania, which is generally based on irregular migration movements. Most of the seasonal migrants to Greece are irregular and work without health insurance or job contracts (Gemi, 2014; Ruedin & Nesturi, 2018). In Italy, seasonal migrants working informally are also very common (Danaj & Çaro, 2016; Fellini & Fullin, 2016). Based on our expert interviews with employment agencies, we understand that the same goes for Germany, where irregular migrants register as asylum-seekers but work informally while in the host country. Other Western European countries are less frequented for seasonal migration although, in the last few years, there has been an increased interest in contract-backed seasonal migration to Malta and the USA. This movement is facilitated via employment agencies which are related to employment offices in the destination countries.

There are several economic sectors which employ a seasonal workforce, depending on the time of year and the respective need for a labour force. This changing demand during the year defines seasonal migrants’ flows from Albania to Western countries. Some of the main economic sectors in these countries which employ seasonal migrants are agriculture – for example, harvesting apples – tourism, construction, domestic cleaning and care services (Kodra, 2021; Maroukis & Gemi, 2013; Piracha & Vadean, 2010). Seasonal migrants work mostly in the so-called 3-D jobs – dirty, dangerous, and demeaning (Maroukis & Gemi, 2013).

This dynamic framework of seasonal migration changed abruptly with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Legal flows of seasonal migration completely ceased; yet irregular movements continued, albeit with a much slower rhythm. We understand from our informants that, even during peak pandemic measures (March to May 2020), there were some seasonal employment opportunities, especially in the healthcare sector. When the measures began to be eased, job positions restarted that were offered by private employment intermediation agencies – which have gradually established themselves in the market over the years. Posts kept appearing on social media, mainly Facebook, which helped with seasonal employment in Greece, Germany, Italy and Malta. The ever-expanding social networks, a consequence of the growth in mobility of Albanians, also served as sources of information for potential seasonal employment, which was mostly undocumented.

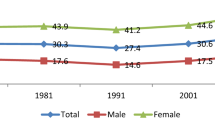

Albanian migration has always been a clearly gendered phenomenon, with a changing gender balance over time (Vullnetari & King, 2011). Traditionally, Albanian migration featured predominantly men but, according to recent official data, the distribution is nowadays more equal – 52% men and 48% women (INSTAT, 2020). The more-balanced gender structure is attributable to two factors: the family-reunion stage that has followed male-led migration and the fact that most return migration (more than three-quarters in fact) is of men, many of whom then seek to re-migrate (INSTAT, 2014, 9). Male emigrants were particularly hard-hit by the post-2008 economic crisis in Greece, which decimated the construction sector where many Albanian men worked on an informal basis.

In our interview sample there were 10 women, all employed as domestic workers and cleaners. Although some of them lost their jobs in the destination countries during the pandemic, they continued to find work by circulating to different countries, benefiting from personal connections and cross-border networks. As Ida (55) told us:

I have been a domestic worker for several years now. I usually work in Switzerland in the winter, staying there for three months, returning to Albania for one week and then back to Switzerland… In the summer I prefer to work in Ulcinj [a tourist town in Montenegro, close to the border with Albania] in different hotels. I managed to work in Switzerland during the pandemic too… I travelled with the group I always go with, with the same two old drivers who will probably continue taking women to work in Northern Italy or Switzerland as domestics and cleaners until they retire [laughs].

4 Seasonal Migration According to Traditional or New Destinations

4.1 How Can We Live on 40 Euros per Month of Social Assistance?

The ongoing phenomenon of high migration rates from Albania may be considered a ‘wicked problem’. According to King (2021), a wicked problem is a problem that is extremely difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete information, contradictory forces, changing circumstances, multiple layers of complexity and interdependencies with other problems. We classify the mass out-migration from Albania as a wicked problem, since this phenomenon is characterised by young, educated and qualified people while, at the same time, there are still high potential rates of migration. At the same time, there is no obvious ‘silver bullet’ to settle this problem. Albania is still locked in the phase of on-going large-scale migration (Gëdeshi & King, 2021; King & Gëdeshi, 2019). In addition to high unemployment, endemic corruption, the unfavourable business climate, informal markets, low-standard education and health services and widening socio-economic and spatial differences, the Covid-19 pandemic has added to these structural push factors. As migration is still regarded as a valve to counter high unemployment rates, the closure of borders raised the pressure on the scarce employment possibilities. This was more evident for the group of migrants who depend exclusively on seasonal migration to make a living, and for whom the nominal social assistance of 40 euros per month constituted an ‘unliveable’ wage. They adapted to the new normality by shifting to new destinations, finding gaps in the outbreak limitations, following new paths of migration or temporarily changing their ways of living, as evidenced by Zeni, a 28-year-old male:

Before the pandemic started, I worked as an assistant cook on cruises. Hard work but well paid ... During the summer (2020) I worked in a restaurant in Montenegro but mainly with their delivery service. It's not the same thing, but at least I'm not out of work ...

Our informants tell us that seasonal migrant employment opportunities during the pandemic era have been in the economic sectors sustained by labour migrants. The pandemic has affected economic sectors differently. According to studies on the impact of Covid-19 on EU industries (De Vet et al., 2021; Juergensen et al., 2020; Uğur & Akbıyık, 2020), the digital industry and the healthcare sector have performed well during the pandemic, enabling industries like chemicals, construction and the food and drinks sector to probably experience a V-shaped recovery from the crisis. However, sectors that are dependent on human contact and interaction – such as cultural and creative industries and the tourism, travel and aerospace sectors (due to the decrease in mobility and tourism activities) – have been substantially hit by the crisis (Nižetić, 2020).

While there was a decline in demand for labour in the sectors of tourism, services, construction or maintenance, the same does not hold for the agricultural and healthcare sectors. The agricultural sector is directly linked to the demand for food, which has not diminished during the pandemic, reflecting a different consumption behaviour when compared to tourism, hospitality, restaurants or construction, which have seen a significant decline (Newson, 2020). Overall, despite the restrictions, the demand for migrant workers remained as high as before, especially in the agricultural and healthcare sectors (Gamlen, 2020). Looking at the importance of the so-called ‘critical professions’, including healthcare, food, services like childcare, elderly care and critical staff for utilities, the European Commission released new ‘practical advice’ on 30 March 2020 to ensure that cross-border and frontier workers within the EU, particularly those critical professions, could reach their workplace (Marcu, 2021).

This fact is also confirmed by the bilateral agreement between Albania – traditionally an origin country for seasonal migrants – and Greece, traditionally a destination country in need of workers.Footnote 3 Following the same logic and looking for seasonal migrants, Italy clearly delineated the number of jobs available for seasonal migrants.Footnote 4 The seasonal migration routes to Germany and Malta were, in contrast, channelled mainly through intermediation agencies. On the flip side of the coin, irregular seasonal movements continued almost all year, except in March and April 2020 when border restrictions were too tight.

4.2 Seasonal Migration to Greece

During the 1990s, the migratory movements of Albanians to Greece were mainly irregular, circular or temporary (Maroukis & Gemi, 2013). Migrants worked in agriculture during the harvest seasons and, especially during the summer, in tourism, construction, small-scale factories or housekeeping. In the late 1990s there were some 550,000 seasonal migrants working in Greece informally (Maroukis & Gemi, 2013; Reyneri, 2001), equivalent to one in six of the entire Albanian population. Due to the legalisation procedures set by the Greek government in 1998, most of these seasonal migrants became permanent and decided to stay indefinitely in Greece (Gemi, 2017). After 2008, however, especially with the economic crisis, it was estimated that nearly 140,000 Albanian migrants returned to the home country from Greece, with some re-migrating to Western European countries (Çaro, 2016).

The seasonal movement of migrants also continued during the hard pandemic years of 2020–2021. This movement was undertaken either in a regular fashion – through employment contracts signed by Greek employers and Albanian employees – or irregularly. In May 2020, after 2 months of complete lockdown in March and April, Albanian media outlets announced the signing of a bilateral agreement between Albania and Greece for seasonal employment in Greece, which requested a much larger number of seasonal workers than in previous years. Greece needed 10,000 employees, most of them in agriculture.Footnote 5 This news was immediately followed by massive numbers of applications, exceeding 7000 per week.Footnote 6 This sudden increase in the number of applicants can also be explained by the simplification of the procedures: the application was made free of charge, without visa restrictions or consulate procedures, with a low cost of movement and with priorities for workers with previous seasonal migration experience. However, with the deterioration of the pandemic situation, in June 2020 Greece announced the complete closing of borders for new seasonal job-seekers and, at the same time, postponed the expiry date of the work permits for seasonal workers already in Greece to 31 December 2020.Footnote 7 Based on the data announced in media outlets, the last quarter of 2020 saw between 20,000 and 24,000 Albanian seasonal workers in Greece and 2000–2500 workers who had Greek citizenship and documentation but who lived in Albania and moved continuously.Footnote 8 Most seasonal migrants were employed in agriculture – the harvesting of fruits such as cherries, grapes and lemons, as well as olives. Some of these workers were employed in tourism – mainly on the Aegean islands – and some skilled workers in construction. Fluctuations in the numbers of Covid-infected people in Greece also defined the restrictions in travel across the border, ultimately reducing access to employment opportunities, despite the latter being plentiful, as Agron (45, male) confirms:

I worked in agriculture in Greece. I usually worked around three months a year and earned enough to sustain my family, wife and two kids, for the entire year. This year the expenses of going to Greece – the PCR test, travel expenses, other documents – are too much but how can I live on 4,800 Lek (40 euros) a month social assistance?

More specifically, in August 2020, the Greek government announced that seasonal workers who had left Greece did not have the right to re-enter the country, whether or not they already had a residence permit. On 20 November, Kapshtica – one of the most important land border-crossing points from Albania to Greece – was closed until 4 December, while the remaining point (Kakavija) continued to have a crossing limit of 750 persons per day (essential travel only). Paulin, a 40-year-old male, explains the problem:

My brother, who lives in Greece, keeps trying to convince me to go there to work because there is much to do. But I can’t go because of the restrictions. I would work on the farm, of course, without a contract. I am afraid I could get stuck there and my wife would be here alone with two children for an indefinite time.

4.3 Seasonal Migration to Italy

Although Greece remains by far the main destination, Italy is also a favourable country for seasonal transnational migrants. Those employed in ‘essential’ sectors during the pandemic – such as healthcare or the agri-food sector – benefited from special decrees issued by the Italian government which aimed to ensure the normal functioning of these sectors. Italy also implemented a regularisation programme with the goal of providing a legal status to migrants working illegally in these sectors (Triandafyllidou, 2022).

Starting from June 2020, the Italian government eased quarantine measures and facilitated the circulation of seasonal workers, particularly in agriculture, by re-opening the border. While most productive sectors in Italy were affected by the crisis, the agricultural sector was the only one that had maintained employment rates close to those of 2019 and had been growing (Palumbo & Corrado, 2020). The circulation of seasonal workers was facilitated by the intervention of the Italian government which, through a special decree in July 2020, determined the quotas of seasonal migrants for the year. Of the total quota of 30,850, 18,000 were reserved for employees in agriculture and 6000 in transport, construction and touristic-hotel services. Albania was one of the countries benefitting from this decision.Footnote 9

From our interview with Ardian, a male employee (aged 46) of an overland transport agency which generally focuses on transporting seasonal workers from Albania to Italy, we heard that the pandemic months saw an increase in employment-related travel as opposed to family and tourist visits, which were very limited. There was a high demand for labour in these sectors (agriculture, health and care) but, due to the restrictions, only those who had a work permit or contract could travel:

This year [2020] there is a surprising increase in circulation for employment purposes generally in the agricultural, healthcare and family assistance sectors. Seventy per cent of my passengers during this period have travelled for employment purposes in these sectors.

The movement of healthcare personnel gained more media attention due to the sensitivity of health matters during the pandemic. In March 2020, the Council of Ministers of Albania decided in favour of helping the Italian Republic with healthcare specialists, physicians and nurses, in light of the challenging conditions presented by the pandemic. The fund for their compensation was fuelled by a reserve budget, with a monthly salary of 2500 euros for nurses and 3000 for physicians. The Albanian and Italian media outlets interpreted this initiative as a good diplomatic move but it is worth mentioning that there were at least 3000 applications to join this group completed by Albanian medical staff. It seems as though the primary goal of this category of migrants was to take advantage of the possibility to be paid better than in Albania, at least for some months. In fact, fear of infection was scarcely mentioned by the interviewees – their economic survival under the conditions of the pandemic seemed to prevail compared to preserving their health.

4.4 Seasonal Migration to Germany

Germany typically needs 300,000 seasonal workers per year (Augère-Granier, 2021). The typology of seasonal migration to Germany is still underexplored as it is a relatively new trend in migration from Albania. Seasonal and circular migrants are generally subsumed within asylum-seeker flows – which is related to how they register as asylum-seekers and, at the same time, work informally, mainly in low-skilled sectors such as agriculture, maintenance, cleaning and nursing (Gëdeshi & King, 2022; Guichard, 2020). Considering the recent trends in the shaping of the labour force in Albania according to labour demands in Germany, we believe that the number of regular Albanian migrants to Germany, whether seasonal or permanent, will continue to grow.

There is a growing number of programmes offered as professional or university-level courses which address the so-called regulated professions and through which a person could find employment in Germany (nurses, hairdressers, electricians etc.). Lessons in the German language are offered free of charge by multiple training centres. At the University of Shkodra, since 2018 the number of students registered on the BA in Nursing degree programme has increased from 80 to 120 per year. According to questionnaires organised by the Alumni Office of the University of Shkodra, 97% of the applicants registered with the goal of leaving Albania for an EU country.

In the case of seasonal migration to Germany, two main categories of migrant exist: irregular migrants who travel with the goal of presenting themselves as asylum-seekers and to work informally in the meantime; and students who travel via employment agencies which assist them in finding jobs. In addition to the private employment agencies, there are different international programmes operating in Albania as well, which play an intermediary role for potential seasonal migrants in Germany.

The pandemic disrupted this normality which temporary migrants had already created and built upon for years. Some, who were ready to emigrate and had a new job and a new life waiting for them in a new country, were left stranded, waiting for borders to reopen to foreigners (Triandafyllidou & Nalbandian, 2020). Some of the interviewees confirmed that they had already signed contracts with employers in Germany but ended up stuck in Albania.

Gjon, a 25-year-old male, interrupted his studies in Albania to work in Germany. His parents live in Albania, while his brothers and sisters live with their families in London. His pathway to Germany followed the route of many other migrants: first he was encouraged by friends who were already there and who told him about the large number of jobs that existed in Germany. He worked informally there for the first 3 months and then went back to Albania because his parents needed some support. For the last 3 years he has been leading this life between Germany and Albania. According to Schengen rules, Albanian citizens cannot stay for more than 3 months in an EU country and cannot work without a work permit. As Gjon worked informally, he had to go back after 3 months although, as he explains, this was not always the case: ‘I know that I can’t stay more than three months in Germany, but there is a solution to that too. My biometric passport can’t stay, but I can’. When asked how that was possible, he answered: ‘You just have to know the right people, you give them your passport and then they arrange everything’. As he says, it is not the person him- or herself who travels – only the passport. While the irregular migrant keeps working in the destination country, he gives the passport to someone to pass it through the border, get it stamped by border controls and then return it to the migrant, who never left the host country. After 3 years of temporary contracts, Gjon contacted a private employment agency in Albania which found him a job in a textile factory: ‘The agency arranged everything – the transport, accommodation and work contract for three months. But the prices I paid were much higher than if I organised it myself…’. He went back to Albania in February 2020 to stay for a few weeks but then found that he could not return to Germany because of the border restrictions. Meanwhile he had a new work contract waiting for him as soon as Albania and Germany both decided on the regulations of movement.

4.5 Seasonal Migration to Montenegro

Montenegro is another destination country for seasonal and circular migration from Albania. The migrants are mostly daily workers, generally in the construction industry and tourism. Montenegro is highly dependent on foreign seasonal workers in the construction sector (ILO, 2020). Moreover, a significant share of seasonal work in tourism in Montenegro is performed by foreign workers. The decline in tourism during the pandemic resulted in a reduction in labour demand in this sector, while there was still a need for workers in construction, mainly in private firms and households.

From the in-depth interviews we see that Albanian seasonal migrants work informally in Montenegro. Most have primary or lower-secondary education and, as there are more frequent opportunities for employment and better wages in Montenegro, they go there to work in agriculture, tourism and construction – sectors which pay much less in Albania. Their journeys are similar: they start out daily from the two northern customs points of Albania at around 3 or 4 a.m. – generally with friends in the same car in order to share the travel costs. They stop in Tuz, where they wait for potential employers from Ulcinj, Budva and Podgorica to come and choose the workers. The luckier ones have created and maintained stable connections with employers, so they go directly to their workplaces. Family connections or acquaintances also notify them as soon as an employment opportunity comes up. They usually get paid 15 euros per day. Some of the seasonal migrants who used to work in Greece and Italy and who subsequently could not travel there during the pandemic chose to work in Montenegro. The flows depended on the restrictions – higher when the restrictions were a bit more relaxed and lower when the restrictions were tight, depending on the cost and nature of the Covid test required. As Martin (54, M) said: ‘I always used to get high wages, because I am a specialist mason, a profession that I have practised for many years in Greece, Germany and recently in Montenegro’.

5 Emerging Key Players in the Field

5.1 Job Agencies

Job agencies and social networks play a key role in defining seasonal migration. Several such intermediation agencies operate in Albania for employment in Germany and Malta. Based on expert interviews with representatives of these agencies, we understand that they offer advice only and are not based on any signed agreements between the destination and origin countries. They have connections to the employment offices in the destination countries, which send weekly updates on the number of vacancies and the nature of the available positions. For tourist destinations like Malta, the professions in demand are in hospitality and tourism: cooks, gardeners, security guards, hairdressers, child-carers etc. In 2020, since this sector suffered a decrease in activity, the number of applicants also fell. However, according to Oriola (32, F), a travel-agency representative, there has been a movement of people via informal means:

We arrange seasonal employment with Germany only for students since there is not yet an agreement like that with Greece or Italy. But we know that the number of irregular seasonal migrants is high – and it was high even during the pandemic.

For countries that are already EU members, the legislation of intermediation job agencies regulates the choice of destination country, the type of immigrant who will migrate and the treatment of the migrants during their stay in the destination country (Koroutchev, 2020). Albania also operates within a legal framework, according to which finding a job abroad can be done only by licensed employment agencies. To exercise its activity, the agency must be registered as a business and equipped with the relevant license for ‘Labour Market Mediation’.Footnote 10 For the employment of Albanian citizens abroad, the agency implements all the bilateral agreements between the Albanian government and the respective host countries. Such employment agencies operate with Malta as well. Again according to Oriola:

Before the pandemic we sent seasonal workers to Germany, Belgium, Malta and other countries of Europe to work over the summer. We had a rented location in Germany which we were forced to give up because of the border closing, as we couldn’t afford the rent of the place due to the inability to send workers there.

5.2 Family and Social Networks

The pace at which the pandemic took hold around the globe, as well as the many unknowns surrounding the virus, caught countries off guard. The role of family connections and social networks that had always characterised Albanian migration showed itself to be even stronger during the pandemic. According to the Bank of Albania, in the last quarter of 2020 remittances appear to have rebounded to higher amounts than during the same period in 2019 (Topalli, 2021). This positive indication can be explained by the support that emigrants provide for family members and relatives in their country of origin, especially in times of crisis and difficulty.

A swift reaction from policymakers with regards to supporting seasonal workers, who compose one of the most impactful groups of employees in the lives of Albanian families, was clearly lacking. The influence of social networks and especially of ‘weak ties’ and ‘bridging ties’, has been shown to be powerful in generating employment opportunities. For many people during the pandemic, ‘strong’ ties remained strong, as family members and friends stayed in touch, although sometimes in not the most convenient, i.e. face-to-face, of ways (Settersten et al., 2020).

Family connections and other social networks impacted on the decision to emigrate and the destination country both before and after lockdown (Kopliku, 2016). The importance of networks is obvious when choosing the destination country and especially when securing an informal job. Joni (25, M) had this to say:

My two brothers live in Germany where I go often, stay and work for three months. Now they have found me a job there, as a driver, so I was planning to go again but got stuck because of the virus. I had even arranged a meeting at the German Embassy to get a visa.

Luigji (52, M), who works as a plumber in the Netherlands, told us that he has been in touch for years with an Albanian there who owns a real-estate company. The company buys dilapidated houses from the bank at low prices and sells them, completely restored, at a much higher price. The restoration work on the houses is done by Albanian workers whom he hires from Albania.

For years I have been working in the Netherlands with this company owned by a friend of mine. As soon as he obtains a new house, he gives me and some of my friends a phone call and we head there. This year we got stuck in Albania in March and April, despite having a lot of work ready to be done in the Netherlands. Right after the movement restrictions were loosened, around the end of May, we restarted work. We moved with fake vaccination certificates … [vaccination in Albania had only begun for medical personnel]. Other than that, we also travelled by bus, not plane. The control is much stricter in airports because they mistakenly take us for drug-traffickers heading for Rotterdam.

5.3 Employment in Albania

The Albanian government has never managed to target seasonal or return migrants with specific and meaningful policies to facilitate their re-integration when left unemployed in Albania (Çaro, 2016). This lack of attention was emphasised even more during the difficult period of the pandemic, when seasonal migrants became stuck in Albania due to the sudden outbreak. According to Albanian procedures, they had to stop by the Regional Labour Office (RLO) and self-declare their unemployment. Our expert interview with a representative of this office stated that there was a decreasing number of ‘self-declared unemployed workers’ – returnees among them – because:

-

of the limited possibilities for movement during the pandemic;

-

of the fact that people do not trust these offices to provide them with a job according to their qualifications;

-

young returnees do not want to be integrated in the Albanian labour market; they prefer to find ways to re-migrate – especially through vocational training;

-

unemployed individuals in the 40–60 age cohort are not really interested in short-term contracts, because they do not want to lose their ‘economic assistance’ (a welfare payment allocated to poor and unemployed people), which is very difficult to be re-obtain once they are out of the system; and

-

most of the jobs they offer are ‘women’s jobs’ (mainly in the chain production industry).

In Albania, seasonal and circular migrants are job-seekers in the same sectors (agriculture, construction, cleaning, caring). Most of them do not apply for RLO services because they do not believe in their efficiency or do not know about them at all. Very few are interested in the employment programmes, about which they are very sceptical and which they also consider to be bureaucracies which are impossible to follow through. Thus, they wait for the borders to be re-opened and to migrate again, as Andi (M, 30) suggests:

I will use the payments that I will get from this job [international programme support] to leave again. There are middlemen who have promised to ensure my re-emigration for a price of €1,000.

According to the interviews, within the group of seasonal migrants, the most vulnerable appear to be those migrants without a profession or trade, who had learned to work as assistants or basic helpers in the sectors of agriculture, construction or services. Workers with a profession, on the other hand, such as plumbers, electricians and flooring specialists, have managed to gain employment in private-sector construction companies or small businesses in Albania, as confirmed by Artan (45, M):

I work for a construction company in Italy, which has an Albanian owner. However, throughout this year [2020] there wasn’t much work in Italy so I have worked here, in Albania. The amount of work available here was considerable, both for construction companies and for families. It is becoming increasingly hard to find professionals [trade experts] in Albania, as the best ones leave to work abroad…

6 Conclusions

Among the responses to the Covid-19 pandemic were lockdown measures and border restrictions. Both had a serious impact on seasonal migration. Migrants were not able to reach their work because of the restrictions and the closing or downsizing of the businesses in the destination countries reduced the demand for labour. This situation resulted in many migrants becoming stuck in or having to return to their origin country. The response to the crisis followed the trends of the pandemic and the regulations of movement. The agricultural and healthcare sectors in developed countries, dependent to a great extent upon the employment of seasonal migrants, witnessed an increase in the demand for labour. Consequently, although with a slower rhythm and through different mechanisms, seasonal and circular migration continued.

This situation resulted in a change to the seasonal migrant movements from Albania, now adapted to this way of life for years. The shifting demands and restrictions during the Covid years defined seasonal migrants’ flows from Albania, which were shaped according to the restriction rules and the performance of different sectors of the economy. Based on bilateral agreements with the destination countries, on the call for seasonal workers from the latter and on the continuity of irregular migration, seasonal migrants from Albania mainly worked during the pandemic in agriculture and healthcare. There was a decrease in the labour-force demand for tourism, hospitality, restaurants and construction, which heavily affected those target groups during the pandemic months.

This chapter has analysed the path chosen by Albanians who are used to make a living out of seasonal migration and who had to remain in Albania because of the pandemic. These paths remain quite varied although generally similar traits can still be summarised:

-

Seasonal migration followed the path of restriction measures and border closures – border crossings of those aiming for seasonal employment were higher in periods of lower infection rates and lower in times of high infection.

-

Alternative ways, generally irregular, to access seasonal migration work mainly in agriculture and healthcare were still found. Both sectors continued having a large demand for employees throughout the pandemic and seasonal workers made use of the opportunities provided by middlemen to leave by road between countries. Such scenarios often include the forging of documents needed for travel, like certificates of vaccination or Covid-test results.

-

Political decision-making, such as agreements signed between Albania and Greece for seasonal employment or between Albania and Italy for the employment of healthcare workers, were greatly utilised. Opportunities created in destination countries that had exhibited a need for a migrant labour force for years, such as Germany, were also pursued.

-

The geographical proximity of Montenegro as a country bordering Albania served as an alternative employment option and was used especially by workers from northern Albania. Depending on the protocols and demands for labour in Montenegro, mainly in construction, seasonal workers made use of the short distance to the border for daily circulation and employment in Montenegro.

-

Employment was oriented towards the few job openings offered by the domestic private sector in Albania, mainly in the services (plumbing, electrical installations, construction, agriculture and tourism) which, despite offering much lower wages than in Western countries, provided a lifeline during the period of spiking unemployment rates in Albania. The relative ease of circulation and more lenient public health measures applied in Albania from May 2020 onwards facilitated this kind of employment.

The pandemic re-emphasised the strong role that social networks play in the various typologies of migration from Albania, be they seasonal, permanent or return migration. Our study thus reinforces the message from Chap. 2 by Louise Ryan on the key function of migrants’ social networks in ‘unsettling’ times of crisis and turbulence. Intermediary employment agencies also continued to play an important role in shaping the new features of seasonal migration in the traditional destination countries of Greece and Italy, as well as in new ones such as Germany or Malta. Although Greece and Italy remain the most common host countries for regular seasonal migrants, there is also a growing number of circular migrants to and from Montenegro. Germany is emerging as a preferred destination but it attracts a diversified target group (students, asylum-seekers and seasonal migrants), whereas employment in Malta is possible only through the intermediation of employment agencies, which renders the movement more official and regulated.

The pandemic further exposed the vulnerability of seasonal migrants from Albania, illustrated by the lack of supportive policies aimed to facilitate their circulation, the insufficient employment opportunities available in Albania and the social instability to which this group is exposed in the perspective of the country of origin. This raises difficult questions about seasonal migrants’ future, which remains, by its very nature, strongly dependent on the destination country.

Notes

- 1.

This information was given by representatives of the employment agencies contacted for this chapter.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sy5DSvP89E4, Episode of ‘Wake Up’ entitled ‘What is happening with employment in Greece?’).

- 9.

- 10.

Law no. 15/2019 ‘On the promotion of employment’ and DCM No. 101 dated 23.02.2018 ‘On the organisation and functioning of Private Employment Agencies’.

References

Augère-Granier, M. (2021). Migrant seasonal workers in the European agricultural sector. European Parliamentary Research Service.

Azzarri, C., & Carletto, C. (2009). Modeling migration dynamics in Albania: A hazard function approach (Policy Research Working Papers 4945). World Bank.

Barjaba, J. (2021). Remittances to Albania: Before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Remittances Review, 6(1), 41–54.

Bartlett, W., & Oruc, N. (2021). Labour market in the Western Balkans 2019 and 2020. Regional Cooperation Council.

Çaro, E. (2016). ‘I am an emigrant in my own country’: A profile of Albanian returnees from Greece. Journal of Science and Higher Education Research, 1(1), 9–25.

Çaro, E., Bailey, A., & Van Wissen, L. J. G. (2014). Exploring links between internal and international migration in Albania: A view from internal migrants. Population, Space and Place, 20(3), 264–276.

Danaj, S., & Çaro, E. (2016). Becoming an EU citizen through Italy: The experience of Albanian immigrants. Mondi Migranti, 2016(3), 95–108.

De Vet, J., Nigohosyan, D., Núñez Ferrer, J., Gross, A., Kuehl, S., & Flickenschild, M. (2021). Impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on EU industries. European Parliament, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies.

Fellini, I., & Fullin, G. (2016). The South-European model of immigration: Cross-national differences by sending area in labour-market outcomes and the crisis. In E. Ambrosetti, D. Strangio, & C. Wihtol de Wenden (Eds.), Migration in the Mediterranean (pp. 32–56). Routledge.

Gamlen, A. (2020). Migration and mobility after the 2020 pandemic: The end of an age? International Organization for Migration.

Gëdeshi, I., & King, R. (2021). The Albanian scientific diaspora: Can the brain drain be reversed? Migration and Development, 10(1), 19–41.

Gëdeshi, I., & King, R. (2022). Albanian returned asylum-seekers: Failures, successes, and what can be achieved in a short time. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 24(3), 479–502.

Gemi, E. (2014). Transnational practices of Albanian families during the Greek crisis: Unemployment, de-regularization and return. International Review of Sociology, 24(3), 406–421.

Gemi, E. (2017). Albanian migration in Greece: Understanding irregularity in a time of crisis. European Journal of Migration and Law, 19(1), 12–33.

Guichard, L. (2020). Self-selection of asylum seekers: Evidence from Germany. Demography, 57(3), 1089–1116.

ILO. (2020). Covid-19 and the world of work: Rapid assessment of the employment impacts and policy responses. International Labour Organization.

INSTAT. (2014). Femra dhe meshkuj në Shqipëri, Women and Men in Albania. http://www.instat.gov.al/media/1736/women-and-man-in-albania-2014.pdf

INSTAT. (2020). Diaspora e Shqipërisë në shifra [Albanian Diaspora in figures]. INSTAT.

Juergensen, J., Guimón, J., & Narula, R. (2020). European SMEs amidst the Covid-19 crisis: Assessing impact and policy responses. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 47(3), 499–510.

King, R. (2021). On Europe, immigration and inequality: Brexit as a ‘wicked problem’. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 19(1), 25–38.

King, R., & Gëdeshi, I. (2019). New trends in potential migration from Albania: The migration transition postponed? Migration and Development, 9(2), 131–151.

Kodra, M. (2021). Circular migration and triple benefits: The case of Albanian migrants to Italy. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 12(4), 31–39.

Kopliku, B. (2016). Return migration in Shkodra region: What’s the next step? In M. Zbinden, J. Dahinden, & A. Efendic (Eds.), Diversity of migration in South-East Europe (pp. 111–134). Peter Lang.

Koroutchev, R. (2020). Seasonal workers before the Covid-19 era: Analysis of the legislation within the context of Eastern Europe. Journal of Liberty and International Affairs, 6(1), 100–111.

Mai, N. (2011). Reluctant circularities: The interplay between integration, return and circular migration within the Albanian migration to Italy. European University Institute Research Repository, METOIKOS Case Study.

Mara, I., Landesmann, M., & European Training Foundation. (2022). ‘Use it or lose it!’ How do migration, human capital and the labour market interact in the Western Balkans? European Training Foundation. https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-04/Migration_Western%20Balkans.pdf

Marcu, S. (2021). Towards sustainable mobility? The influence of the Covid-19 pandemic on Romanian mobile citizens in Spain. Sustainability, 13(7), 4023.

Maroukis, T., & Gemi, E. (2013). Albanian circular migration in Greece: Beyond the state? In A. Triandafyllidou (Ed.), Circular migration between Europe and its neighbourhood (pp. 68–88). Oxford University Press.

Newson, M. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on seasonal and circular migration in Europe and Central Asia. Webinar presented at the FAO Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia.

Nicholson, B. (2004). The tractor, the shop and the filling station: Work migration as self-help development in Albania. Europe-Asia Studies, 56(6), 877–890.

Nižetić, S. (2020). Impact of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic on air transport mobility, energy, and environment: A case study. International Journal of Energy Research, 44(13), 10953–10961.

OECD. (2021). Multi-dimensional review of the Western Balkans: Assessing opportunities and constraints. OECD.

Palumbo, L., & Corrado, A. (Eds.). (2020). Covid-19, agri-food systems, and migrant labour: The situation in Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain and Sweden. European University Institute.

Piracha, M., & Vadean, F. (2010). Return migration and occupational choice: Evidence from Albania. World Development, 38(8), 1141–1155.

Reyneri, E. (2001). Migrants’ involvement in irregular employment in the Mediterranean countries of the European Union. International Labour Organization.

Ruedin, D., & Nesturi, M. (2018). Choosing to migrate illegally: Evidence from return migrants. International Migration, 56(4), 235–249.

Settersten, R. A., Bernardi, L., Härkönen, J., & Antonucci, T. C. (2020). Understanding the effects of Covid-19 through a life course lens. Current Perspectives on Ageing and the Lifecycle, 45, 100360.

Topalli, M. (2021). Ndikimi i pandemise Covid-19 tek remitancat ne Shqiperi. Banka e Shqiperise.

Triandafyllidou, A. (2022). Spaces of solidarity and spaces of exception: Migration and membership during pandemic times. In A. Triandafyllidou (Ed.), Migration and pandemics (pp. 3–21). Springer.

Triandafyllidou, A., & Nalbandian, L. (2020). ‘Disposable’ and ‘essential’: Changes in the global hierarchies of migrant workers after Covid-19. International Organization for Migration.

Uğur, N. G., & Akbıyık, A. (2020). Impacts of Covid-19 on global tourism industry: A cross regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100744.

Ullah, A. A., Nawaz, F., & Chattoraj, D. (2021). Locked up under lockdown: The Covid-19 pandemic and the migrant population. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 3(1), 100126.

Vadean, F., & Piracha, M. (2009). Circular migration or permanent return: What determines different forms of migration? In G. S. Epstein & I. N. Gang (Eds.), Migration and culture (pp. 467–495). Bingley.

Vullnetari, J., & King, R. (2011). Remittances, gender and development: Albania’s society and economy in transition. I. B. Tauris.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kopliku, B., Çaro, E. (2023). Adapting to the New Normality: The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Seasonal Migration from Albania. In: Jakobson, ML., King, R., Moroşanu, L., Vetik, R. (eds) Anxieties of Migration and Integration in Turbulent Times. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23996-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23996-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-23995-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-23996-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)