Abstract

The purpose of this chapter is to examine the role of religion and ritual in facilitating access to and security over land among migrants in peri-urban Zimbabwe. The chapter is based on ethnographic fieldwork carried out among Malawians settled in Lydiate, an informal settlement in Zimbabwe’s Norton peri-urban area. The study shows that though they are not the only sources of access to and security over land, religion and ritual-based forms of authority—the Nyau cult and witchcraft—play a role in land matters. Migrants turn to the enchanting, dramatic, yet dreadful Nyau cult to access and reinforce their ownership of land. Because it is feared and respected by adherents on account of its association with deathly symbols, the cult is able to yield and secure land for those who seek it in its name. Others secure their land against expropriation from fellow migrants through the eccentric means of witchcraft. The migrants do not choose these alternative forms of authority out of preference; very often there are no formal institutions that they can use. Legal courts and local authorities are often unsympathetic toward their interests. Thus, migrant squatter settlements have become dynamic spaces with novel forms of authority regulating access to coveted resources such as land.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction and Background

This chapter focuses on how displaced transnational migrants establish themselves in rough peri-urban spaces in destination countries. Peri-urban refers to transitional spaces where people, resources, and goods connect and move between rural and urban areas. Roughness in this study metaphorically denotes the difficulties experienced by migrants in destination countries by virtue of their foreign descent. In this chapter, I focus on displaced Malawians in Zimbabwe’s peri-urban spaces. The transnational quality of Malawi-to-Zimbabwe migration can be traced to the colonial period. Malawian descendants originally came to Zimbabwe as labor migrants during the period of colonial labor migration (Chibaro/Mthandizi), between the 1890s and the 1970s (Daimon, 2015). The displacement of Malawian descendants in Zimbabwe resulted from the events of the infamous Fast Tract Land Reform Program, dubbed the “Third Chimurenga,” which resulted in white colonial farmers losing farms to local Zimbabweans (Moyo, 2005). Malawian descendants, who constituted the majority of the farm workers on the white colonial farms in Zimbabwe, were the most affected. Anusa Daimon (2015) affirmed that Zimbabwe’s land reform program was traumatic for farm workers, specifically those of foreign ancestry, as they remained in the shadows and were largely invisible in the politics of land appropriation. Scholars such as Lloyd Sachikonye (2003) and Sam Moyo (2005) observed that prior to land reform, about 4500 white commercial farmers employed an estimated 300,000 to 350,000 farm workers, who together with their families represented about two million people, or nearly 20 percent of the country’s population, of which 11 percent were of Malawian descent.

Ultimately, about 500,000 to 900,000 people were displaced and the livelihoods of approximately two million people were severely disrupted, leaving many without jobs, homes, schools, water, and clinics (Hartnack, 2017). For many Malawian descendants, the land reform destroyed the only home and source of livelihood they had ever known in Zimbabwe since the colonial era. The reform also exposed them to displacement, leaving many impoverished and marooned on farms, while others were forcibly displaced to urban areas and squatter camps such as Lydiate (the area of study) with questionable land rights. In these spaces, Malawian diaspora and their descendants have remained on the margins of the social, economic, and political affairs of Zimbabwe. They have constantly been regarded as “migrants” or “the Other,” as expressed through labels such as Vatevera njanji (those who followed the railway line on foot), Vabvakure (those who came from afar), Mabwidi (those without rural homes), or “totem-less ones” (Daimon, 2015).

The aspect of roughness experienced by migrants at their destination has remained unexplored in African urban research, which has typically analyzed the processes and consequences of migration (Mavroudi & Nagel, 2016; Van Hear et al., 2018). The ground-breaking work by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2005), for example, is largely preoccupied with the drivers of migration on a global scale. Similarly, the detailed studies from the Southern African Migration Project deal with the capital flows that characterize southern African migration (Crush et al., 2015). Why scholars do not pay attention to this matter is not difficult to understand: They generally hold the destination in Africa to be non-problematic and assume that migrants need not do anything to remain therein. Unfortunately, this is an erroneous assumption because—as research is beginning to show—destinations are indeed rough and conflictual (Nyamwanza & Dzingirai, 2020). These places are so rough that migrants have to adopt innovative strategies to remain in certain areas (Bhanye & Dzingirai, 2019; Nyamwanza & Dzingirai, 2019). Migrants who fail to adjust suffer; some return home, often in shame. This element of roughness can therefore not be understated.

Regarding the strategies for surviving roughness, some scholars show that migrants can turn to political patronage to remain established in the contested peri-urban spaces (Bhanye & Dzingirai, 2020; Chirisa, 2014; Scoones, 2015). These scholars note that migrants may vote for powerful political patrons or “big men” in exchange for protection from eviction (Bhanye & Dzingirai, 2020; Muchadenyika, 2015). Other scholars highlight the use of social networks for survival, including biological and fictive kin (Berge et al., 2014; Zuka, 2019). Preliminary evidence also suggests that migrants can establish themselves through religion and the occult. The anthropologist Peter Geschiere (1997), writing about the Maka people in Cameroon, argued that contemporary religious ideas and practices are often a response to modern pressures rather than just a cultural custom. In his famous piece, Religion in the Emergence of Civilization, which detailed the symbolic lives and religious experiences of residents in Çatalhöyük, Turkey, Ian Hodder (2010) highlights the fact that spirituality and religious ritual play a strong role in the establishment of marginal populations. Studying Mozambican refugees in the Tongogara refugee camp in Zimbabwe, Ann Mabe (1994) observes that spiritual beliefs play a vital role in coping with transition and that they extend beyond the refugee camp to impact integration in the country of settlement. A study by Isabel Mukonyora (2008) shows how the Masowe Apostles constructed a theology of hope that sustained their followers in their continued migration through southern, central, and eastern Africa. A study by Jennifer Sigamoney (2018) among Somali migrants in South Africa demonstrates that religion and spirituality play a major role in supporting the resilience of Somali migrants. Thus, migration scholarship shows that religion and ritual are important aspects of the lives of transnational migrants and diaspora communities in destination countries. Nonetheless, the aspect of religion and ritual practices facilitating access to and security over land remains poorly understood.

The purpose of this chapter is to examine the role of religion and ritual in facilitating access to and security over land among migrants in the peri-urban areas in Zimbabwe. The understanding of access in this study is based on Jesse Ribot and Nancy Lee Peluso’s definition (2003, p. 1) that describes it as “the ability to derive benefits from things.” Access is more akin to “a bundle of powers” than to just the notion of a “bundle of rights.” Security over land means the ability to retain or hold on to the land. Security over land is an important matter because the land that migrants hold in peri-urban spaces is also coveted by other parties, including the “natives,” other migrants, the state, and local authorities; all have competing claims.

The chapter is divided into several sections. The first section includes an introduction and background of the study. This is followed by a methodological note presenting the ethnographic fieldwork that guided this study and a brief description of the area of study—Lydiate, Zimbabwe. An overview of the Nyau cult follows. Next, I present key findings of my study on the Nyau cult as a form of authority in access to and security over land and witchcraft as a form of authority in securing land. I conclude that peri-urban migrant squatter settlements have become dynamic spaces with novel forms of authority—the occult and witchcraft—regulating access to coveted resources such as land. The reason why displaced migrants turn to these alternative forms of authority is not because they prefer it but very often there are no formal institutions that they can use. The existing ones, including courts of law and local authorities, are often unsympathetic toward their interests.

Methodological Note

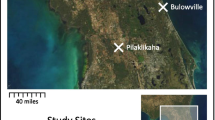

The study is based on ethnographic fieldwork carried out among Malawian migrants (herein referred to as Lydiatians) who settled in Lydiate, a peri-urban squatter settlement in the town of Norton, Zimbabwe. I carried out an 18-month-long fieldwork from May 2018 to January 2019. Through what I termed “partial immersion ethnography,” I was an observer of both the traditional closed squatter community of Lydiate and the greater sphere of the Lydiate area. This micro/macro focus was important because Lydiate is a diverse and fluid community and the people there do things that go beyond the community borders. In the squatter settlement, I was a participant observer in various social spaces, including Nyau ceremonies, church gatherings, and community meetings. I also made observations while taking transect walks inside and outside of the community of Lydiate. Through these observations, I managed to capture the various operations of the Nyau cult, including initiation ceremonies, territorial marking mobility in the community, scary costumes, dances, and violent and dreadful gestures. The observations were complemented by in-depth interviews with 50 purposively selected participants both within and outside the settlement. Selected participants from the community provided insights regarding the role of the Nyau cult in land matters in Lydiate. Other study participants in the community gave insights into the use of witchcraft by fellow migrants to resolve land disputes. In-depth interviews with the caretakers and indigenous owners of farms and agro-residential plots surrounding the Lydiate community focused on the fear that Nyau cult members would appropriate some of the available lands. All the individuals I interviewed provided informed consent. Furthermore, in order to maintain anonymity and confidentiality, all the participants were given pseudonyms. Pseudonyms were necessary because of their unresolved citizenship status, which remains a major issue in the Lydiate community.

Lydiate: A Brief Background

Lydiate is a peri-urban squatter settlement in the town of Norton, Zimbabwe. The settlement also falls under the Zimbabwean Mashonaland West Province, in Ward 14 of the Chegutu Rural District Council. Life in the Lydiate squatter settlement is tough. Just like other squatter settlements in southern Africa, Lydiate is what Owen Nyamwanza and Vupenyu Dzingirai (2020) term a “rough neighborhood.” The biggest challenge migrants face is an acute scarcity of land for settlement. The population in the squatter settlement has grown to about 1200,1 with more than 60 percent of the migrants being between the ages of 18 and 35 (ZimStats, 2013); they now require their own individual plots of land for settlement. The squatter settlement sits on a six-hectare piece of land (L. Rafamoyo, personal communication, June 15, 2018) and the sizes of individual plots vary from one migrant to another, but are generally very small, averaging 50 m. The majority of the housing structures are temporary or semi-permanent shacks made of poles and mud, tin and zinc roofing sheets, and plastic and metal scraps. Local natives victimize the Lydiatians. They perceive them as squatters who should be removed in order to increase the value of the recently developed agro-residential plots adjacent to the squatter settlement. These agro-residential plots owned by indigenous Zimbabweans occasionally exploit Lydiatians for labor. However, some of these properties, together with the large-scale commercial farms to the immediate west, are vacant and often attract the attention of landless migrants in the compound.

In terms of community social organization, the Lydiatians now have internal differences based on the history of the settlement. To begin with, there are vauyi vakare—long-term migrants—who have settled in the core of the settlement. Then there are vauyi vazvino—or recent migrants. These newer migrants are settled on the periphery of the settlement in areas known as kuma nyusitendi (new stands). Leadership in the community is articulately defined. Within the compound there are elected leaders masabhuku (village heads) who maintain a register (bhuku) of the settlement. The masabhuku command respect from the migrants, who regard them as instrumental in facilitating access to land. Some of the village heads are also leaders of Nyau cult ceremonies and initiations.

Lydiatians are very religious. There are various religions in the community, but the dominant ones are Christianity, Islam, and the Nyau cult. There is a mosque by the road and there are multiple churches whose shrines are scattered around and outside the compound. It is common for members to belong to multiple faiths and visitors are similarly expected to participate in different forms of worship. I was invited to attend Islamic ceremonies, but I was also expected to participate in activities organized by local Christian churches. Finally, there is the enchanting and dramatic Nyau cult, giving the settlers a voice and influencing their lives. This cult organizes dances and initiation rites for the youth. The Nyau ceremonies and dances—frequented by many—take place on weekends, usually after church services. Like all other religious leaders, the Nyau leaders are respected by the Lydiatians. They are believed to have powers to inflict harm or bring illness on those who are insubordinate and go against their decisions.

The Nyau Cult

The occult can be defined as the knowledge of the hidden that extends pure reason and the physical sciences (Geschiere, 1997). It also refers to the clandestine, hidden, or secret (Moore & Sanders, 2003). Nyau, also known as Gule Wamkulu, is both a secret cult and a ritual dance practiced among the Chewa people, dating back to the great Chewa Empire of the seventeenth century (UNESCO, 2005). Gule Wamkulu has been classified by UNESCO as one of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity (UNESCO, 2005). Nyau societies operate at the village level but are part of a wide network across the central region and part of the southern regions of Malawi, eastern Zambia, western Mozambique, and areas of Zimbabwe to which Malawians migrated (Ottenberg & Binkley, 2006).

Gule Wamkulu literally means “the big dance.” The dancers (called zilombo, or wild animals) are dressed in ragged costumes of cloth and animal skins and wear masks made of wood and straw that represent a great variety of characters, such as wild animals, spirits of the dead, slave traders, and—more recently—objects such as helicopters (Bhanye & Dzingirai, 2020). Other cult members’ dress code resembles the nyama za ku tchire, a feared animal that appears at the time of a person’s death. There is a kind of hierarchy between the different animals, with some very respected animals such as njobvu (the elephant) and antelope, and feared ones like lions and hyenas (Harding, 2013). Each of these plays a particular, often evil, character that represents certain forms of misbehavior. At that moment in the performances and rituals, Nyau masked dancers are understood to be spirits of the dead. As spirits, the masqueraders may act with impunity (Ottenberg & Binkley, 2006).

The dreadful Nyau cultural traits are an indirect cultural form of resistance, or what James Scott terms “hidden transcripts,” that provide the means to express emotions and make them collective (Scott, 1990). In southern Africa, Nyau’s continued underground operation, mystery, and possible threat have enhanced its reputation for being a law unto itself. Ellen Gruenbaum (1996) explains that cultural practices serve a positive function in maintaining kin cohesion and ethnic identity, both of which are closely guarded and not easily changed. Ian Linden (2011) specifically points out that cultural practices, such as Nyau, are institutions of remarkable resilience and vitality that serve to unite the migrants in times of social stress and act as powerful curbs on the influence of foreign and dominant identities.

The Nyau Cult as a Form of Authority in Access to and Security Over Land

In Lydiate, the Nyau cult plays a significant role in advancing access to and security over land. This means that it facilitates migrants’ security on the land for both settlement and small-scale agricultural production, sometimes at the expense of the indigenes. Through the cult, Lydiatians intimidate the indigenes into releasing part of their land for farming or settlement. The fear is usually targeted s the caretakers or managers of agro-residential plots and farms that surround the compound. Ustowardually, Nyau cult members choose public places to perform their almost supernatural dances and haunting, high-tempo drum rhythms. Occasionally, they move around from the cemetery making ghostly noises and usually end up close to areas that are occupied by the indigenes. The idea of launching their processions from the graveyard is meant to preserve the mystery surrounding the Nyau practice and to scare away non-Chewa people who might be tempted to intrude (Daimon, 2017). When performed at night, these processions scare the caretakers and owners of nearby plots. Because of these practices, the indigenous people are constantly reminded of the power of the occult. When cult members need land, either individually or collectively, it is easier for them to get it because of this fear they instill in the indigenes. This is well demonstrated by the case below.

In 2018, members of the cult targeted a nearby plot owned by Mr. Shumba. The plot is under the care of his 27-year-old caretaker, Edmore Zuze. Without seeking permission, the two members began planting sweet potatoes, the preferred food of the cult members. Fearing persecution and backlash from the cult, Edmore let the members be, even hiding from them. To this day, these members continue to use the plot for other purposes besides farming. Edmore said:

Though I wanted to stop them, I could not. I knew I should not even touch them since they are members of the feared Nyau cult. I did not have any option but to let them be. I was afraid of contradicting them. I also told Mr. Shumba, my master, that the two women are not supposed to be touched since they practice the occult (E. Zuze, personal communication, June 5, 2018).

In a somewhat similar case, 28-year-old Peter Tinhirai, a caretaker at Mr. Zvarevashe’s agro-residential plot, narrated how an active member of the Nyau cult had been farming on his landlord’s plot for many years without permission. Peter confessed that both he and Mr. Zvarevashe are afraid of evicting the cult member (P. Tinhirai, personal communication, June 1, 2018). Rumors circulate that the cult members are brave enough to openly seize land and unleash their powers to cause harm to those who dare to confront them. In the end, caretakers and owners of nearby farms and agro-residential properties choose not to interfere with them.

The cult is clearly instrumental in generating land for some Lydiatians. In fact, this function is so important that many landless young men join the cult in order to secure land. This partly explains why the majority of the cult members are young, often between 14 and 35 years of age. During my study, I identified a number of young men who had already joined the cult to gain recognition and pave their way toward possessing their own physical space. In one case, 19-year-old Tawanda Mamvura stated that he had joined the cult at the age of 14 (T. Mamvura, personal communication, April 6, 2019). Dominic Njanji, a 22-year-old who joined the cult at a young age, had this to say:

I started to participate in the Nyau dances from the age of 16. I joined the cult because I wanted to have respect in the community. If you are not initiated into the cult in this community, it is like you are a nobody here. You are not considered a man and getting physical space for settlement when you grow up might be difficult (D. Njanji, personal communication, April 4, 2019).

Membership in the cult is designed to secure land; once members of the cult become older and have secured their own physical settlement plots in the community, they often leave the cult. A good example is 35-year-old Gift Banda, who was once a very active member of the cult, but left it after securing his space in the compound. Gift now works as a taxi driver, moving between Norton and Lydiate. Gift narrated his story as follows:

I was initiated into the Nyau cult at a very young age: 17. I became very active in the cult for close to 10 years, getting the attention of both the cult leaders and other traditional leaders in the community. When I got married at 27, it was very easy for me to get a portion of settlement land. From that time onwards, my focus moved from frequenting Nyau dances to looking for a livelihood outside the community. I left the dance floor for other upcoming youths. Currently, I spend most of my time driving a taxi to and from Norton town. Nevertheless, once a Nyau cult member, you always remain a member even though you no longer actively participate in the dances. The DNA is still in me (zvichiri mandiri) (G. Banda, personal communication, April 6, 2019).

The Nyau cult has also played a role in neutralizing female power over land matters through the Chewa matrilineal system. In Lydiate, women do not seem to join the Nyau cult, except for a few involved in intricate clapping, singing, dancing, chanting, and responding to the song of the masquerader. Because of the mystery and fear instilled by the male cult members, the female exclusion undercuts their traditional matrilineal control over land. Thus, the Nyau cult being a male-dominated secret society allows male Lydiatians to ritually gain increased importance on land issues, which are predominantly mediated among the Chewa people by a matrilineal system. In Lydiate, the power of the Nyau cult continues to ensure that relations between Chewa men and women—including land matters—remains ambivalent and negotiable.

The cult does not only facilitate securing individual land; more often than not, it also assists migrants—who are usually threatened by indigenes over patrimony—in holding on to their land. These indigenes want to monopolize the land that is currently occupied by the migrants. Indeed, it is no secret that indigenes perceive the migrants as squatters who should be removed in order to increase the value of their recently developed agro-residential plots (Shumba, personal communication, June 23, 2018).

It is against this background that the cult is invoked. Cult members define core Lydiate as a no-go area for other groups apart from Malawian migrants. This marking of territory is frequently done during the weekend through a dramatic procession that is organized around deathly practices. Members of the cult, dressed in phantom costumes of cloth and animal skins, present themselves as walking dead men. They transform themselves into masked white giants, standing or moving around on stilts that dwarf normal human beings. In their territorial marking mobility, they continuously mimic gestures of violence and threaten to beat up locals that come near Lydiate and its compound. The sophisticated, mysterious, and scary customs do not target fellow community members, but rather indigenous outsiders who are seen as potentially dangerous because they want to seize land from the migrants. Needless to say, the locals will not question the tenure of these Lydiatians.

My research has shown that the occult plays a significant role in securing land among Lydiatians. Many people use it to secure land that they would not otherwise have gotten. The agency of the Malawian diaspora in destination countries through the Nyau cult is not new. Since the colonial period, the Nyau cult has been a crucial component of Malawian diasporic agency and identity articulation in Zimbabwe and other southern African countries. Anusa Daimon (2015) asserts that Nyau has offered a platform and social networks to cope with the fears and problems induced by post-independent political turmoil, the Economic Structural Adjustment Programs (ESAP), droughts, and continued state alienation (Daimon, 2015; Delius & Phillips, 2014). What is new about the Nyau cult in this study is that its rich forms of mesmerizing nature and deathly symbols help to facilitate migrants’ security over land in a hostile and foreign environment.

However, the occult has its own limitations. For example, it is not always effective in securing land for every cult member. During my research, I came across a few cases where migrants were dispossessed of their land despite being cult members. It also seems as if modern religions, particularly Pentecostalism, are now more preferable than traditional practices like the Nyau cult (Jeannerat, 2009). This can be ascribed to modern religious practices that allow for more social capital than the Nyau cult, which is associated with secrecy and seems to thrive by instilling fear among non-members. It was not surprising then that some cult members had dual membership—belonging to the cult while at the same time attending modern Pentecostal Christian churches. I came across cases where social networks that were developed through modern churches also facilitated security over land without any controversy. Some migrants, for example, easily retained their land through association with traditional leaders attending the same church.

In contemporary migration studies, the modern church plays a significant role in facilitating the integration of transnational migrants (Dzingirai et al., 2015; Goździak & Shandy, 2002; Hagan & Ebaugh, 2003; Landau & Freemantle, 2010; Levitt & Jaworsky, 2007). A study by Vupenyu Dzingirai et al. (2015) among Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa revealed that the church played a critical role in enabling people to help each other settle, find jobs, and connect to other migrants from their communities. Loren Landau and Iriann Freemantle (2010) observed that modern Pentecostal churches contribute to a broader approach to estuarial life that can be categorized as “tactical cosmopolitanism” and that allows migrants to be in a place but to also be not of that place: to be neither host nor guest. It is also important to note that the existence of two parallel religious beliefs, such as the Nyau cult and modern religions, can serve as a barrier to the establishment of migrant communities, because the two can work in compelling, competing, and contradictory ways. It was common in Lydiate for non-cult members to stereotype cult members as dangerous and capable of causing harm. However, regardless of its shortfalls, the Nyau cult still plays a role in facilitating access to and security over land in Lydiate. The following section deals with witchcraft as a form of authority in securing land among Lydiatians.

Witchcraft as a Form of Authority in Securing Land

Lydiatians also make use of witchcraft to secure plots of land. While the Nyau cult is used to secure land against external threats, witchcraft is often used to protect an individual’s land against fellow migrants. In contemporary African studies, the term witchcraft has been used to cover a variety of activities, often of the nefarious sort like black magic, mystical arts, spells, and enchantment (Comaroff & Comaroff, 1999; Geschiere, 1997; Gluckman, 2012; Moore & Sanders, 2003). Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff (1999) show that there is much witchcraft around the world, although it takes on a variety of local guises. Other scholars demonstrate how the African diaspora and squatter settlements are havens of witchcraft (Hickel, 2014; Moore & Sanders, 2003). In these communities, witchcraft has been used to cause harm to the innocent, take revenge against enemies, or protect one’s assets or resources from dispossession, and as the Camaroff & Camoroff (1999) observed, it produces immense wealth and power—against all odds—at supernatural speed and with striking ingenuity.

During my ethnographic inquiry in the Lydiate community, rumors of witchcraft were common, especially in relation to resource security. Some of the Lydiatians convincingly talked about the squatter settlement being full of trenchant human evil and phantasmic forces of unprecedented power and danger. This power and danger often targeted fellow migrants to enforce land ownership. Land enforcement is done through threats of harm to other migrants. Owing to this fear of danger, people in the community do not encroach onto land that is not theirs, as there are unknown fatal consequences associated with such actions. During my study, some community members openly talked about people in the community who could hurt others with witchcraft if they took their land. Especially among the younger generation of migrants, there are burgeoning fears that the older, first-generation Malawians in the community are able to cast spells of misfortunes—and in extreme cases, turn members of the community into zombies—if they were to ever encroach onto the spaces that these elders occupy. One of the migrants, Magret Petro, had this to say:

Considering the complexity and size of this community, witchcraft happens. I remember a case when one hard-headed old woman seized another community member’s portion of farmland. When she was asked to leave the land, she refused. She even threatened the other person with death until the person left her with the land (M. Petro, personal communication, April 8, 2019).

The use of witchcraft to secure land in the community was also revealed through an interview with Howard Chidyamakava, who said that

cases of disputes, especially over both settlement and farmland are rampant in the community. In this community, if you are not careful of how you deal with other members over land issues, you will die; there is serious witchcraft. The Nyau (zvigure) dominate this community. People here live secret lives and you would not want to take someone’s land if you do not really know the person well. You will be killed over such action if you are not careful (H. Chidyamakava, personal communication, April 8, 2019).

Because of witchcraft, the weak are left with little recourse but to protect or shield themselves by retreating. Some would even opt to lose their land to such people. The 29-year-old Maita Tambwe, for example, was honest enough to say that if she were threatened by witchcraft, she would certainly give the land to the original owner or the claimant (M. Tabwe, personal communication, April 8, 2019).

In another case, 39-year-old housewife Shawn Chikomo, had this to say:

I used to have a small plot just across this community (kwaNhau) and I realized that someone had taken that plot. I did not try to argue with the person, since he is well known for witchcraft. This has happened to me twice. Instead, I just opted to go and find somewhere to farm since I fear people in this community. There are cults and witchcraft in this community. I remember one community member who was threatened with a lightning strike (kuroveswa nemheni) over a piece of land (S. Chikomo, personal communication, April 8, 2019).

Not everyone responded to threats of witchcraft by retreating. In some instances, those who are threatened also dared to fight back supernaturally. Julius Mulochwa, for example, told me that he vowed to turn the whole family of a fellow migrant into zombies after a dispute over a piece of farmland had led to the fellow migrant threatening to bewitch him and his family. Julius said,

I was going to turn his whole family into zombies. He claimed my piece of land, which he clearly knew I have been using for the past three years. What baffled me was that he even threatened to bewitch my family if I failed to give up the land. After realizing that I was not backing off, he retreated and I kept my land.

Thus, as Mavhungu (2012) argues, witchcraft can be a mechanism for the expression and resolution of social tensions and conflicts over resources, although it often disturbs amicable social relations. In other studies (e.g., Dehm & Millbank, 2019; Schnoebelen, 2009) witches have often been found to be persecuted, while some claim refugee status on the basis of being bewitched by others.

In Lydiate, those who are threatened with danger sometimes turn the land dispute over to the community leaders. Getrude Chanza, a 29-year-old woman, invited one of the community leaders, Mr. Matambo, to resolve a land dispute that had erupted between her and an elderly woman who is well known for casting evil spells. To establish peace between the two parties, the community leader decided that the two would share the farmland by dividing it equally.

The evidence presented above demonstrates that migrants can establish themselves through very eccentric means, like witchcraft, regardless of the reluctance among scholars to admit that Africa is still home to practices of witchcraft in the accumulation and protection of resources. In Lydiate, witchcraft was used to secure land against fellow members in the community. Thus, witchcraft and enchantments are real and abundant in Africa; as demonstrated by the above findings, they are common practice in Africa’s emerging urban communities. John Comaroff (1994) has even argued that witchcraft is every bit as expansive and protean as modernity itself—thriving on its contradictions and silences, usurping its media, and puncturing its pretensions. Peter Geschiere (1997) also stressed that witchcraft abounds now and there is a dramatic rise in occult economies in Africa.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated that religious and ritual-based forms of authority—the Nyau cult and witchcraft—while not the only sources of access to and security over land, play a role in land matters. In Zimbabwe’s Norton peri-urban area, Malawian migrants turn to the enchanting, dramatic, yet dreadful Nyau cult to access and reinforce their ownership of land. Because the cult is feared and respected by adherents on account of its association with deathly symbols, it is able to yield and secure land for those who seek it in its name. Others secure their land against expropriation from fellow migrants through the eccentric means of witchcraft. Migrants do not choose these alternative forms of authority out of preference; very often there are no formal institutions that they can turn to. The existing ones, like courts of law and local authorities, are often unsympathetic to their interests. Nevertheless, migrant squatter settlements have become dynamic spaces with novel forms of authority, such as witchcraft and the occult, regulating access over coveted resources. In terms of policy, this study recommends that there is a need for the state and other agencies involved in migration and peri-urbanity in Zimbabwe to come together and craft diverse policies and arrangements that make it possible for displaced migrants to have access to resources and entitlements that enable them to formally survive where they are located on a long-term basis. For now, migrants are left to depend on bizarre forms of authority, such as witchcraft and the occult, sometimes at a great cost to themselves.

Note

-

1.

Demographic figures from the community register kept by community leaders, at Lydiate Farm, 2018.

References

Berge, Erling, Kambewa, Daimon, Munthali, Alister, & Wiig, Henrik. (2014). Lineage and land reforms in Malawi: Do matrilineal and patrilineal landholding systems represent a problem for land reforms in Malawi? Land Use Policy, 41, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.05.003

Bhanye, Johannes, & Dzingirai, Vupenyu. (2019). Plural strategies of accessing land among peri-urban squatters. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 13(1), 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17528631.2019.1639297

Bhanye, Johannes, & Dzingirai, Vupenyu. (2020). Structures and networks of accessing and securing land among peri-urban squatters: The case of Malawian migrants at Lydiate informal settlement in Zimbabwe. African Identities, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2020.1813551

Chirisa, Innocent. (2014). Housing and stewardship in peri-urban settlements in Zimbabwe: A case study of Ruwa and Epworth [D.Phil. thesis]. University of Zimbabwe.

Comaroff, John. (1994). The discourse of rights in colonial South Africa: subjectivity, sovereignty, modernity. American Bar Foundation.

Comaroff, Jean, & Comaroff, John. (1999). Occult economies and the violence of abstraction: Notes from the South African postcolony. American Ethnologist, 26(2), 279–303.

Crush, Jonathan, Chikanda, Abel, & Tawodzera, Godfrey. (2015). The third wave: Mixed migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Canadian Journal of African Studies/revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, 49(2), 363–382.

Daimon, Anusa. (2015). ‘Mabhurandaya’: the Malawian diaspora in Zimbabwe: 1895 to 2008 (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State).

Daimon, Anusa. (2017). ‘Ringleaders and troublemakers’: Malawian (Nyasa) migrants and transnational labor movements in Southern Africa, ca. 1910–1960. Labor History, 58(5), 656–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2017.1350537

Delius, Peter, & Phillips, Laura. (2014). Introduction: Highlighting migrant humanity. In Peter Delius, Laura Phillips, & Fiona Rankin-Smith (Eds.), A long way home: Migrant worker worlds (pp. 1–16). Wits University Press.

Dehm, Sara, & Millbank, Jenni. (2019). Witchcraft accusations as gendered persecution in refugee law. Social & Legal Studies, 28(2), 202–226.

Dzingirai, Vupenyu, Egger, Eva-Maria, Landau, Loren, Litchfield, Julie, Mutopo, Patience, & Nyikahadzoi, Kefasi. (2015). Migrating out of Poverty in Zimbabwe. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3300791

Geschiere, Peter. (1997). The modernity of witchcraft: Politics and the occult in postcolonial Africa. University of Virginia Press.

Goździak, Elzbieta M., & Shandy, Dianna J. (2002). Editorial introduction: Religion and spirituality in forced migration. Journal of Refugee Studies, 15, 129.

Gruenbaum, Ellen. (1996). The cultural debate over female circumcision: The Sudanese are arguing this one out for themselves. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 10(4), 455–475.

Hagan, Jacqueline, & Ebaugh, Helen Rose. (2003). Calling upon the sacred: Migrants’ use of religion in the migration process. International Migration Review, 37(4), 1145–1162.

Harding, Frances. (2013). The performance arts in Africa: A reader. Routledge.

Hardt, Michael, & Negri, Antonio. (2005). Multitude. War and democracy in the age of empire. Harvard University Press.

Hartnack, Andrew. (2017). Discursive hauntings: Limits to reinvention for Zimbabwean farm workers after fast-track land reform. Anthropology Southern Africa, 40(4), 276–289.

Hickel, Jason. (2014). “Xenophobia” in South Africa: Order, chaos, and the moral economy of witchcraft. Cultural Anthropology, 29(1), 103–127.

Hodder, Ian. (Ed.). (2010). Religion in the emergence of civilization (pp. 220–267). Cambridge University Press.

Jeannerat, Caroline. (2009). Of lizards, misfortune and deliverance: Pentecostal soteriology in the life of a migrant. African Studies, 68(2), 251–271.

Landau, Loren B., & Freemantle, I. (2010). Tactical cosmopolitanism and idioms of belonging: Insertion and self-exclusion in Johannesburg. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(3), 375–390.

Linden, Ian. (2011). Missions and politics in Malawi. By K. Nyamayaro Mufuka.Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1977, Africa, 49(1), 88–89.

Levitt, Peggy, & Jaworsky, Nadya. (2007). Transnational migration studies: Past developments and future trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 129–156.

Gluckman, Max. (2012). Politics, law and ritual in tribal society. Routledge.

Mabe, Ann. (1994). Taking care of people through culture: Zimbabwe’s Tongogara Refugee Camp. In J. L. MacDonald, & A. Zaharlick. Selected Papers on Refugee Issues: III. Arlington, (pp. 78–97). American Anthropological Association.

Mavhungu, Khaukanani. (2012). Witchcraft in Post-colonial Africa. Beliefs, techniques and containment strategies. Langaa RPCIG.

Mavroudi, Elizabeth, & Nagel, Caroline. (2016). Global migration: Patterns, processes, and politics. Routledge.

Moore, Henrietta L., & Sanders, Todd. (Eds.). (2003). Magical Interpretations, Material Realities: modernity, witchcraft and the occult in postcolonial Africa. Routledge.

Moyo, Sam. (2005). The land question and land reform in southern Africa. National Land Summit, Johannesburg, South Africa, July, 27–31.

Muchadenyika, Davison. (2015). Land for housing: A political resource–reflections from Zimbabwe’s urban areas. Journal of Southern African Studies, 41(6), 1219–1238.

Mukonyora, Isabel. (2008). Masowe migration: A quest for liberation in the African Diaspora. Religion Compass, 2(2), 84–95.

Nyamwanza, Owen, & Dzingirai, Vupenyu. (2019). Surviving hostilities in alien cityscapes: Experiences of Zimbabwean irregular migrants at plastic view informal settlement, Pretoria East, South Africa. African Journal of Social Work, 9(2), 16–24.

Nyamwanza, Owen, & Dzingirai, Vupenyu. (2020). Big-men, allies, and saviours: mechanisms for surviving rough neighbourhoods in Pretoria’s Plastic View informal settlement. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 1–13.

Ottenberg, Simon, & Binkley, David. (2006). Playful performers: African children's masqueraders. Transaction Publishers.

Ribot, Jesse, & Peluso, Nancy Lee. (2003). A theory of access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181.

Sachikonye, Lloyd. (2003). The situation of commercial farm workers after land reform in Zimbabwe. Harare: Farm Community Trust of Zimbabwe Report. https://mokoro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/situation_commercial_farm_workers_zimbabwe.pdf

Schnoebelen, Jill. (2009). Witchcraft allegations, refugee protection and human rights: a review of the evidence. UNHCR, Policy Development and Evaluation Service.

Scott, James. (1990). Domination and the arts of resistance: Hidden transcripts. Yale University Press.

Scoones, Ian. (2015). Zimbabwe’s land reform: New political dynamics in the countryside. Review of African Political Economy, 42(144), 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2014.968118

Sigamoney, Jennifer. (2018). Resilience of Somali Migrants: Religion and spirituality among migrants in Johannesburg. Alternation Journal, 22, 81–102.

UNESCO. (2005). Gule Wamkulu. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/gule-wamkulu-00142

Van Hear, Nicholas, Bakewell, Oliver, & Long, Katy. (2018). Push-pull plus: Reconsidering the drivers of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(6), 927–944.

ZimStats. (2013). Survey of Services 2013 Report. https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/publications/Economic/Informal-sector/SS-2013-Report-Updated.pdf

Zuka, Sane Pashane. (2019). Customary land titling and inter-generational wealth transfer in Malawi: Will secondary land rights holders maintain their land rights? Land Use Policy, 81, 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.039

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bhanye, J. (2023). “Emerging Forms of Authority in Land Access?”: The Occult and Witchcraft Among Malawian Migrants in Peri-urban Zimbabwe. In: Goździak, E.M., Main, I. (eds) Debating Religion and Forced Migration Entanglements. Politics of Citizenship and Migration. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23379-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23379-1_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-23378-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-23379-1

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)