Abstract

Successful research environment requires joint effort by individual researchers, research groups and the organization. This chapter describes the basic principles and good research practices in the context of the research environment and serves as a guide to good, responsible research for research newcomers – researchers at the beginning of their scientific career. In this chapter we will help you navigate the organizational pathway to doing good research. The first step to understanding your rights, obligations and responsibilities in research is knowing that they exist. This chapter offers an introductory level orientation to codes, rules and regulations but also serves as a guide on how to identify whether your organization goes above and beyond offering guidance and assistance regarding research integrity or whether it provides a bare minimum or even nothing at all, and who/what you can turn to in the latter case. Furthermore, this chapter also describes the responsibilities that you as a researcher have towards the organisation regarding the importance of maintaining research integrity, so that you are aware of your accountability and the possible consequences if you disregard organizational responsibility for responsible research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

What This Chapter Is About

Successful research environment requires joint effort by individual researchers, research groups and the organization. This chapter describes the basic principles and good research practices in the context of research environment and serves as a guide to good, responsible research for research newcomers – researchers at the beginning of their scientific career. In this chapter we will help you navigate the organizational pathway to doing good research. The first step to understanding your rights, obligations and responsibilities in research is knowing that they exist. This chapter offers an introductory level orientation to codes, rules and regulations but also serves as a guide on how to identify whether your organization goes above and beyond offering guidance and assistance regarding research integrity or whether it provides a bare minimum or even nothing at all, and who/what you can turn to in the latter case. Furthermore, this chapter also describes the responsibilities that you as a researcher have towards the organisation regarding the importance of maintaining research integrity, so that you are aware of your accountability and the possible consequences if you disregard organizational responsibility for responsible research.

Case Scenario: Research Environment and Research Integrity

This hypothetical scenario was adapted from a narrative concerning the links between research environments and research integrity. The case scenario was developed by the Members of The Embassy of Good Science and is available at the Embassy of Good Science. The case below is published under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license, version 4.0 (CC BY-SA 4.0).

After 6 months of working as a novice researcher in a research lab at a university school, you meet up with a colleague who graduated with you and is now working as a novice researcher in a commercial research organization. She tells you that she may have encountered a potential research misconduct concerning intellectual property. She knew what she had to do because the company is very committed to making sure all employees are fully informed about all existing rules and regulations. Her action prevented the misconduct. That conversation made you think that you were never been briefed or informed in detail about rules and regulations regarding research when you signed your employment contract with your organization. You heard your mentor casually mention “standard rules of conduct in research,” expecting you to know what they are. The day after your meeting with your colleague, you check your school’s webpages for information on research integrity. Although there is no explicit mention of research integrity, your University’s website refers to its own code of conduct as well as the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. Furthermore, a university-wide academic integrity complaints procedure and a research integrity committee are mentioned but details of which, however, cannot be found on the university’s public webpages. After talking to your fellow novice researchers, you realize that they too are uncertain about whether your school has written guidelines for research integrity. You also realize that they feel pressurized to generate more and more research outputs and that insecurity, linked to short-term contracts and scarce opportunities for professional advancement, means that they perceive the incentives to succeed in research and academia as outweighing the incentives to comply with the norms of good research practices. They not only feel that your school does not adequately promote research integrity but that that pressure comes within the organization, also as a result of the culture of “publish or perish” After talking to them you realise that there is more to this problem than just ignorance or integrity issues with individual novice researchers and that their views could indicate an environmental problem in academia.

Questions for You

-

1.

In light of this case scenario, what do you think which person(s) or groups should be responsible for the early-career researchers’ general lack of knowledge concerning the university’s research integrity guidelines, codes of conduct and complaints procedures? What are the reasons for your answer?

-

2.

In what ways could a research organization make its research integrity standards, guidelines and processes more visible to its researchers, especially early-career researchers? What initiatives should be promoted in a research organization in order to engage early-career researchers with research integrity standards, guidelines and processes?

-

3.

Thinking about the ways in which your organization currently engages early-career researchers with research integrity standards, guidelines and processes, what could be done to improve such engagement at the level of your organization and the level of your department or laboratory?

The Responsibilities of the Organization: Above and Beyond, or the Bare Minimum?

Good research practice from the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity:

-

Research institutions and organisations promote awareness and ensure a prevailing culture of research integrity .

When starting at a new job in a new research organization you have to understand that an organization is a living organism – a system with organized structure that functions as an individual entity and is, as all organisms are, prone to constant change. One change that has been having a huge momentum in Europe in recent years is the initiative to encourage activities that show commitment of organizations to make research integrity (RI) and responsible research in general as a top priority. Empowering sound and verifiable research and fostering a research integrity culture, thus creating a proper research environment, is now empowered by embedding these principles as requirements in EU funding schemes. As research environment is a dimension that needs to be considered by all involved stakeholders, activities conducted in order to foster good research practices and a culture of research integrity will impact researchers at all levels.

When we talk about organization as a system, the terms organizational climate and organizational culture are sometimes used interchangeably or considered as complementary constructs. The two terms are different. Organizational climate is usually defined as shared perceptions of policies, practices and procedures experienced by the employees, as well as the behaviours the employees perceive as rewarding. It is considered to be the measurable manifestation of organizational culture, which is defined as the system of basic assumptions, deep values and beliefs that are prevalent in the organization. Organizational culture is something that has to be built, maintained and nurtured by supportive environment.

As a part of organizational culture, research integrity has become an integral part of a university’s mission, vision and strategy. For example; universities in France will, in the near future, in what seems to be the first national initiative of its kind, go as far as requiring Ph.D. recipients to take an integrity oath on the day they successfully defend their thesis. Research integrity is also dependent on human factors – collegiality, openness, reflection, shared responsibility and work satisfaction are vital elements of a successful working environment. As a novice researcher, you should try, from the very beginning of your career, to comply with the highest standards of ethics and integrity in the performance of your research.

How can you figure out the ethical landscape at the very start of your career? The first step to understanding your rights, obligations and responsibilities is knowing that they exist.

Rules, codes and regulations can be created by the organization itself but also by national or international bodies. They can have different names and vary in scope, but they are always a written set of instructions issued by an organization. Depending on the scope of action, codes can cover issues prescribed by legal regulations such as: human subject’s protection, animal care, intellectual property and confidentiality, legality and mechanisms to identify and procedure for reporting and dealing with research misconduct. Other than binding legal issues, codes can also cover fundamental principles of research which serve organisations in creating and preserving an environment for responsible research. Fundamental principles presented by the most widely recognized and accepted documents – European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (All European Academies 2017) and Fostering Integrity in Research (US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2017), might not be identical in the naming of the principles but the meaning of the principles in RI perspective is similar (Table 1.1).

Not all research or academic organizations are as big or as well developed to have the resources to promptly and adequately inform you about all rules and obligations regarding research. That does not mean you are not required to follow them or that your rights are not protected by them. Organizational guides and codes should be easily accessible on the organization’s webpages and/or intranet. You should be provided with adequate training, tailored to the research discipline and the type of organization, and briefed about standard rules of conduct in research. Bear in mind that the organizational support structure is usually proportional to the size and complexity of the organization. Apart from having binding documents about responsible research, your organization should have established channels to facilitate an open dialogue at and between all levels; from management and senior researchers to novice researchers and other members of staff. Ideally, your organization should, apart from the standard rules and regulations, develop and implement a research integrity promotion plan (RIPP). This is a document that describes, on a general level, how the organization promotes research integrity and which concrete methods are employed or are being developed to foster research integrity and to deal with allegations of breaches of research integrity. Procedures to increase transparency of research investigation procedure and safe and effective whistle-blowing channels and the protection of alleged perpetrators should also be implemented in line with the legal principle of the presumption of innocence – someone accused of research misconduct is considered innocent until proven guilty.

When navigating the research environment, it is always advisable to consider the human factor. Some organizations are very organized. Some are not. Even though an organization may be committed to following the prescribed rules, do not expect to be given a clear and user-friendly version of these rules upon arrival. Some organizations have rules and regulations because they had to comply with national or international regulations. Other organizations have them because the management is devoted to actively promoting responsible research. Some organizations are understaffed, so the lack of organizational documents may not necessarily reflect the moral of the organization. In brief, even if your organization does not have instructions for the new employees written on a (virtual) bulletin board, that does not mean that they do not exist, so no matter whether you were briefed or not these rules apply to you and you should be governed by those rules.

Here is some advice for you on how to navigate responsible research environment in your organization:

-

1.

Always get familiar with existing laws, codes and regulations in the organization and country where you work. If you are a member of a professional organization or if you are professionally bound to the code of ethics of your profession, check whether the professional code is aligned with that of your organisation. Some organizations may provide a checklist with sources and links to different guidelines and rules of procedure for good research practice available online. Do not forget to get familiar with international principles and EU standards such as The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, principles prescribed for different professions (e.g., The Declaration of Helsinki or Convention on Biological Diversity) and national guidelines, but first and foremost to the documents and guidance provided by your organization.

-

2.

Consider that different views of research ethics around the world reflect differences in culture and legal frameworks, which can lead to differences in regulations. For example, the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has a very expansive definition of personal information that may warrant protection, whereas in the United States (US), there is a narrower (and often domain-specific) characterization of privacy-sensitive information. Even within the EU, there are differences among EU member countries – the examples are different laws on stem-cell research and human embryos. Differences in regulations unfortunately may lead to ethics dumping – the practice of researchers trained in cultures with rigorous ethical standards to go and conduct research in countries with laxer ethical rules and oversight, in order to circumvent the regulations, policies, or processes that exist in their home countries.

-

3.

Keep in mind that codes and regulations change and can evolve. For example, The Nuremberg Code; which is a set of research ethics principles for human experimentation was created by the US vs. Brandt et al. court case, as a result of the Nuremberg trials at the end of the World War 2. The core elements of the Nuremberg Code are the requirements for voluntary and informed consent, a favourable risk/benefit analysis, and the right to withdraw from a study without consequences. That standard was confirmed in 1964, when the WMA’s Declaration of Helsinki was endorsed and again specified that experiments involving human beings needed the informed consent of participants. The Declaration of Helsinki has been updated overe the years, so make sure that you consult its latest version. Another example is the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, funded by the US Public Health Service. The study was conducted between 1932 and 1972 at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to evaluate the natural history of untreated syphilis in African American males. The study was conducted for 40 years without ethical review and denied participants the effective treatment for this curable disease. The study became a milestone in the history of US research regulations, as it was conducted without ethical re-evaluation in spite of both The Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki being accepted and established as a standard during the study. The aftermath of the public disclosure of the Tuskegee study led to the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research and the National Research Act that requires the establishment of institutional review boards (IRBs) at institutions receiving federal support.

Codes and regulations can also change due to scientific advancements that lead to new fields of research (e.g., the emergence of experimental psychology) or new technologies (e.g., gene editing, artificial intelligence). The changes can also come in response to changes in cultural values and behavioural norms that evolve over time (e.g., perceptions of privacy and confidentiality).

-

4.

Consider emerging ethics topics, even if they are not listed or mentioned in current codes of your organization, such as bystander risk (impacts of research on other people; e.g. genetic testing and genetic research, second-hand exposure to a contagious disease) big data and open science (concerns about the potential to compromise privacy), and citizen science (involving community participation in science, allowing the research population to become researchers).

Good research practice from the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity:

-

Research institutions and organisations demonstrate leadership in providing clear policies and procedures on good research practice and the transparent and proper handling of violations.

Knowing, understanding and using existing codes and regulations for good research is important and useful, but there may be times when you are in doubt about how what is written in a code translates into real life. Therefore, it is important to learn how to interpret, assess, and apply different research rules and how to make decisions to act ethically and responsibly in different situations or at least know who to turn to when in doubt. To put it simply: pure existence of the codes does not make an ethical environment. Or, in words of Aristotle: “One swallow does not a summer make.”

If codes, rules and regulations are the foundation of research integrity culture, building strong pillars to rest upon, establishing research ethics structures is the next crucial step for organizations to ensure proper research environment.

Different organizations may have different supportive mechanisms to ensure that researchers adhere to research ethics and integrity requirements. Depending on the size and the type of the organization, key organizational bodies and staff dealing with research ethics and integrity might quite vary in name and scope of work. It is important to understand that, depending on type of research organisation, you may encounter organisational bodies (or individuals) with various scope of activities regarding research ethics and integrity. This may seem confusing at first, as the concepts of ethics and integrity may seem intertwined and actually, for the most part, they are. Research ethics (RE) is the term that encompassed fundamental moral principles and research integrity (RI) is the quality of having moral principles, defined as active adherence to the ethical principles and professional standards essential for the responsible practice of research. Both of them are a necessary part of responsible conduct of research.

Ideally, your organisation will have all necessary structures, processes, and dedicated and adequately trained staff to uphold best research practices and standards, and deal with procedures relevant to the various research areas and disciplines within the organisation. Listed below are some of the common research ethics and integrity bodies (names might vary). If there is only one of these at your organisation, the scope of their responsibilities is probably wider and you can still contact them regarding any doubt and insecurity you might have about responsible research.

Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board is probably the most common body at academic and research organizations, because it has the longest history. Research Ethics Committees were developed after the World War 2, particularly in response to The Nuremberg Trials, as bodies responsible for oversight of medical or human research studies. The role of an Ethics Committee is to scrutinise research proposals and ensure that the proposed research adequately addressed all relevant ethics issues. This means that they make sure that proposed research protocols protect rights, safety, dignity and well-being of participants, that research protocols involving animals follow the highest animal care standards and that they facilitate and promote ethical research that is of potential benefit to participants, science and society. In smaller organisations that do not necessarily have other bodies, the role of the Ethics Committee would also be to facilitate and promote research integrity and good research practices, to have mechanisms to identify and procedure for reporting and dealing with allegations of breaches of research integrity (research misconduct).

Board/Office/Commission for Research Integrity is a body that promotes responsible research conduct, serves as a knowledge base for questions regarding research integrity and research misconduct, informs on policies and procedures in and outside of the organization, handles allegations of research misconduct and conducts investigations, advises on administrative action and also responds to allegations of retaliation against whistle-blowers. It is responsible for providing advice for researchers on how to adhere to responsible research practices, usually through guidelines, checklists and other documents in which good research practices are presented. The organisational structures of RI committees and their responsibilities regarding cases of research misconduct may vary depending on the organisational or national regulations. For example, the Office for Research Integrity in the US is a governmental body that has monitoring and oversight role to ensure that researchers and organisations which receive federal funding for health research comply with existing regulations; it offers support to further good practice research and promote integrity and high ethical standards, as well as to have robust and fair methods to address poor research practices and misconduct.

Another individual position you may encounter at your organisation is the Research Integrity Officer (RIO), a professional with a complex role. An organisation’s RIO promotes responsible research, conducts research training, discourages research misconduct, and deals with allegations of or evidence of possible research misconduct. The details of an RIO’s job vary from country to country, but the position is mandatory in many. For example, in US organisations, a RIO serves as the liaison between the federal Office for Research Integrity and the organisation of the researchers. In the EU, countries have different requirements and roles for their RIOs, but their task is essentially the same. Some countries do not have such bodies, and their role is most often taken by Ethics Committees.

Your organisation may have a Research Integrity Ombudsperson or Confidential Advisor on Scientific Integrity or Research Integrity Advisor. The aim of such an advisor is to promote fair, non-discriminatory and equitable treatment related to research integrity within the organisation and improve the overall quality of the research working environment. Such a position should be well known in the organisation, and there should be a low threshold for contacting this person. Researchers who experience research integrity dilemmas or have come into an integrity-related conflict should be able to discuss their case with the ombudsperson in a strictly confidential manner. The function of the ombudsperson should be clearly separated from a formal research integrity committee or ethics committee, so that it is clear to researchers that contacting the ombudsperson does not imply a formal registration of an allegation but a confidential and informal assistance in resolving research work-related conflicts, disputes and grievances (including, but not limited to complaints/appeals of researchers regarding conflicts between supervisor(s) and early-stage researchers).

Good research practice from the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity:

-

Research institutions and organisations support proper infrastructure for the management and protection of data and research materials in all their forms (encompassing qualitative and quantitative data, protocols, processes, other research artefacts and associated metadata) that are necessary for reproducibility, traceability and accountability.

Even as an early-career researcher you probably realise that, while doing research, dealing with a fair amount of different types of data is inevitable. Ten years ago the Science journal polled their peer reviewers from the previous year on the availability and use of research data, and, about half of those polled stored their data only in their laboratories. If you had walked in any type of research organisation 10 years ago you would have had probably been briefed about keeping your lab notebook records and advised about keeping your data somewhere other than your lab desktop computer. Today, when we talk about data management, we go well beyond keeping your lab or research notebook in order. While maintaining a lab notebook is still essential for anybody performing research as a document of completed work so that research can be replicated and validated; or a legal document to prove intellectual property/invention, data management on an organisational level entails much more. It comprises the infrastructure (technology, services and staff support), training for researchers, and policies on data management (DMPs). Therefore, you should expect from your organisation to provide instructions and policies regarding data curation (repositories), management, use, access, publishing, and sharing. Regarding the technology for data management, your organisation should provide appropriate storage media that enables collecting, organizing, protecting, storing, and sharing data. It should also inform you about available data repositories, networks and different authentication systems. Research organisations should make DMPs easily accessible and organisations’ websites should provide extensive information about the concept of data sharing in general, as well as detailed information on DMP requirements and how to comply with them. Services and staff support for data management are highly dependent on the amount of funding and size of an organisation because the amount of work and time involved in these processes is extensive and costly. Some organisations have whole departments and others at best a single person for data management.

In 2019, Science Europe released its Practical Guide to the International Alignment of Research Data Management, and, as a follow-up, compiled the document to showcase some best practices. The document also demonstrated the variability of data management processes in different organisations. Although the readiness to develop DMPs can differ according to discipline, most research funders require researchers to include a DMP in their project proposals. You should expect from your organisation to have in place the structures and procedures to facilitate data management and curation procedures that are aligned with FAIR principles, which say that data should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Bear in mind that researchers’ knowledge about research data management could be limited in countries and organisations where open science policies are not well developed. This leads to misunderstandings about the need to store and archive data. For detailed guidance on data practices and management throughout the lifecycle of research data and instructions to preparation of data management plans (DMPs) see Chap. 5.

Good research practice from the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity:

-

Research institutions and organisations reward open and reproducible practices in hiring and promotion of researchers.

No matter whether you have been in research for some time or you are a novice researcher, you have probably heard the catchphrase “publish or perish!” because it has been uttered in whisper by stressed and burned-out researchers all over the world for years, putting pressures on individual integrity and potentially fostering practices harmful to scientific research. Publish or perish culture thrives on metrics (number of articles published and impact factors of journals) but fails to adequately take societal and broader impact into account. Some aspects of research are indeed quantifiable and cannot be and will not be ignored, but recent efforts towards more inclusive evaluation scheme of research and researchers could be a “game-changer”, meaning that yes, you are still required to publish, but the scientific efforts that translate better to a broader community will not be ignored.

When it comes to hiring and promotion in research, the need for transparency should be self-explanatory, but what does promoting open practices mean in reality? Geographically speaking, Europe might be ahead of the curve in endorsing and implementing changes as the new framework programme Horizon Europe makes Open Science mandatory throughout the programme and includes Open Innovation as one of three framework pillars. What does this mean for you? Although the attitude and the level of commitment of the organisation toward endorsing open science principles could vary and very much depend on the human factor, there is no reason for you not to be aware of the change to come and strive to fulfil the general idea of quality. Producing quality science would imply producing substantive, impactful science, science that reaches broader audience and addresses valuable questions, but is also reliable enough to build upon. This mean that evaluation and appraisal procedures may assess a researcher’s contribution to addressing societal needs and publishing all research completely and transparently, regardless of whether the results were positive or negative. This would also imply implementing open research practices and embedding these skills in training of early-career researchers, making preliminary results and final results available to the general public, potential users and the research community, in order to facilitate broader assessment and accountability of research.

There are also indications that the EU is moving towards a structured CV which would include Responsible Indicators for Assessing Scientists (RIAS), and other related information. For example; the department of psychology at LMU München added a paragraph to a professorship job advertisement which asks for an open science statement from the candidates: “Our department embraces the values of open science and strives for replicable and reproducible research. For this goal we support transparent research with open data, open material, and pre-registrations. Candidates are asked to describe in what way they already pursued and plan to pursue these goals.” Another example is University of Liège, where depositing papers in the repository is now the sole mechanism for submitting them to be considered when researchers underwent performance review.

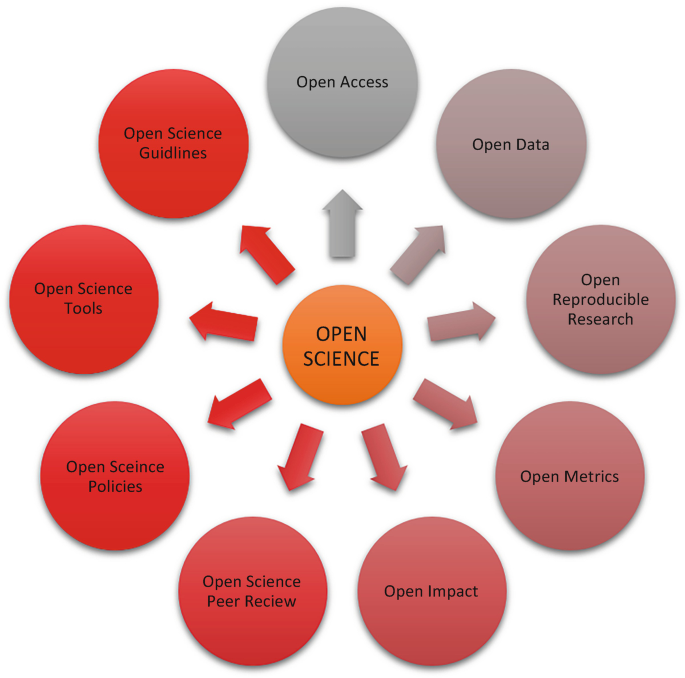

Check whether your organisation has procedures related to the publication and communication of research results, such as preregistration, preprints, and online repositories, the organisational approach to open access, FAIR data curation, expectations about the use of reporting guidelines, procedures for avoiding predatory journals, strategies for responsible peer review practices, and mechanisms to support and acknowledge public communication of research findings. Also, check whether your organisation is ahead of the curve in promoting Open Science (Fig. 1.1) check for procedures and practices through the organisation’s own website or other established platforms on organisational or national level, check whether your organisation has signed any declaration relevant to Open Science.

Core principles of Open Science. For details, see the FOSTER project

The Responsibilities of the Researcher

Ask not what your organisation can do for you – ask what you can do for your organisation.

While The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (ECoC RI) provides general guidance for good research practices and serves as a framework for self-regulation, the document that details your role, responsibilities and entitlements as a researcher is The European Charter for Researchers. The Charter is a set of general principles and requirements that addresses all researchers in the European Union at all stages of their career, covers all fields of research and takes into account the multiple roles that researchers can have.

Being a researcher is highly related to context and not defined only by job positions, formal qualifications level of education or by seniority at work. According to The Frascati definition; Researchers are professionals engaged in the conception or creation of new knowledge. They conduct research and improve or develop concepts, theories, models, techniques instrumentation, software or operational methods. The tasks performed depend on job characteristics and personal strengths but have to be related to research and innovation. Activities of a researcher are many, but first and foremost entail: conducting and evaluating research and innovation, applying for research funding, managing projects and teams, managing, sharing and transferring the generated knowledge (including through scholarly communication, science communication to society, knowledge management for policy, and knowledge transfer to industry) and higher education teaching.

As an early-career researcher, you should keep in mind that everything you do reflects upon your organisation. So be sure to comply with the highest values and ethical standards and aim at excellence. Even as a novice researcher, at a beginning of your career be aware that your organisation will treat you as a responsible adult and will hold you accountable. Also, depending on the applicable rules, your organisation might be held accountable for your wrongdoing, so, even if you are there for a brief amount of time (post-doctoral or project-based position) remember that you are a part of the research environment and are expected to contribute to a positive, fair and stimulating research culture.

Science is by definition a joint endeavour and you should learn to accept responsibility because that is what being accountable entails. Accountability refers to an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility for one’s actions, meaning that, when individuals are accountable, they understand and accept the consequences of their actions for the areas in which they assume responsibility. Remember that you, as an employee, have contractual and legal obligations. That basically means that you are liable in case of breach of contract and you have to adhere to such regulations by delivering the required results (e.g. thesis, publications, patents, reports, new products development, etc), as set out in the terms and conditions of the contract or equivalent document. You should be familiar with the strategic goals, seek all necessary approvals before starting your research or accessing the resources provided. You should, at all times, keep a professional attitude. This included maintaining a professional etiquette at workplace – respectful and courteous demeanour towards colleagues and respect in the sense of responsibilities (e.g. informing your supervisor if you are not able to meet deadlines).

As a researcher, you should, first and foremost, focus your research for the good of mankind and for expanding the frontiers of scientific knowledge. You should be guaranteed the freedom of thought and expression, and the freedom to identify methods by which problems are solved, according to recognized ethical principles and practices. But, bear in mind that there is a difference between using research freedom and abusing it. You should, by all means, recognize the limitations to this freedom that could arise as a result of particular research circumstances or operational constraints (e.g. for budgetary or infrastructural reasons or, especially in the industrial sector, for reasons of intellectual property protection). Such limitations should not contravene recognized ethical principles and practices in research. When it comes to ethical principles, you should adhere to the recognized ethical practices and fundamental ethical principles appropriate to your discipline, as well as to ethical standards defined in different national, sectoral or organisational codes of ethics. It is highly recommended to conduct ethics self-assessment at the very beginning of planning your research. Ethics self-assessment helps getting your research protocol ethics-ready, as it may give rise to binding obligations that may later on be checked through ethics checks and reviews. Consider that ethics issues arise in many areas of research and, as of recently, major scientific journals require researchers to provide ethics committee approval before publishing research articles. You should also adopt safe working practices, in line with national legislation, including taking the necessary precautions by preparing proper back-up strategies.

As we mentioned before, Open Science practices should be the norm, especially when performing publicly funded research, as they improve the quality, efficiency, responsiveness of research and trust in science. You should guarantee open access to research publications and research data and foster innovation in sharing research knowledge as early as possible in the research process, through adequate infrastructures and tools. You should ensure, in compliance with your contractual arrangements, that the results of your research are disseminated and exploited. Be public and open about your research. There are, of course, legitimate reasons to restrict access to certain data sets (for instance in order to protect the privacy of research subjects) so be guided by the principle “As open as possible, as closed as necessary”. Ensure that your research activities are made known to society at large in such a way that they can be understood by non-specialists, thereby improving public understanding of science. Direct engagement with the public will help researchers better understand public interest in priorities for science and technology and also their concerns.

You should seek to continually improve yourself by regularly updating and expanding your skills and competencies. This may be achieved by a variety of means including, but not restricted to, formal training, workshops, conferences and e-learning.

Do not be afraid to diversify your research career, as research community is diverse in talents and expertise and can produce a wide range of research outputs (from scholar publications to scientific advice for policy makers, science communication to the public, higher education teaching, knowledge transfer to industry, and many others). Explore different career paths within the research profession, so that your talent finds the best place to produce richer research results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

If You Want to Learn More

If You Want to Learn More

The Embassy of Good Science

-

Case scenario – Research Environments and Research Integrity

-

Guidelines – Creating a map of the normative framework informing and governing the state of Good Science

-

Education – Literature and tools in research integrity and ethics

Published Articles

-

Ashkanasy N, Wilderom C, Peterson M (2011) The handbook of organizational culture and climate. Sage Publications, New York

-

Fischer BA (2006) A summary of important documents in the field of research ethics. Schizophr Bull 32(1):69–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj005

-

Moher D, Naudet F, Cristea IA, Miedema F, Ioannidis JPA, Goodman SN (2018) Assessing scientists for hiring, promotion, and tenure. PLoS Biol 16(3):e2004089. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004089

-

Qiao H (2018) A brief introduction to institutional review boards in the United States. Pediatr Investig 2(1):46–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/ped4.12023

-

Qin J (2013) Infrastructure, standards, and policies for research data management. In: Sharing of scientific and technical resources in the era of big data: the proceedings of COINFO 2013. Science Press, Beijing, pp 214–219

-

Schneider B, Ehrhart MG, Macey WH (2013) Organizational climate and culture. Ann Rev Psychol 64(1):361–388. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143809

-

Ščepanović R, Labib K, Buljan I, Tijdink J, Marušić A (2021) Practices for research integrity promotion in research performing organisations and research funding organisations: a scoping review. Sci Eng Ethics 27(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00281-1

-

Science Staff (2011) Special collection. Dealing with data. Challenges and opportunities. Science 331:692–693. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.331.6018.692

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2017). Fostering integrity in research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. http://nap.nationalacademies.org/21896

-

Zohar DM, Hofmann DA (2012) Organizational culture and climate. In: Kozlowski SWJ (ed) The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology, vol 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 643–666

Guidance

-

The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity - framework for self-regulation across all scientific and scholarly disciplines and for all research settings. ECoC is a reference document for research integrity for all EU-funded research projects and as a model for organisations and researchers across Europe. All European Academies (ALLEA). (2017). https://allea.org/code-of-conduct/

-

The Bonn PRINTEGER Statement – Working with research integrity; guidance for research performing organisations

-

SOPs4RI Toolbox – Standard Operating Procedures and Guidelines that Research Performing and Funding Organisations can use to develop their own Research Integrity Promotion Plans

-

LERU – The League of European Research Universities (LERU) is a prominent advocate for the promotion of basic research at European research universities comprising of League of European Research Universities 23 leading universities pushing the frontiers of innovative research

-

Science Europe – Implementing Research Data Management Policies Across Europe: Experiences from Science Europe Member Organisations

-

Ask Open Science – Hosted by Bielefeld University, discussion (Q & A) on Open Science

-

The LSE Impact Blog – Six principles for assessing scientists for hiring, promotion, and tenure

-

The European Charter for Researchers – The European Charter for Researchers is a set of general principles and requirements which specifies the roles, responsibilities and entitlements of researchers

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barać, L. (2023). Research Environment. In: Marusic, A. (eds) A Guide to Responsible Research. Collaborative Bioethics, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22412-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22412-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-22411-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-22412-6

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)