Abstract

After reviewing previous research strategies applied to evaluate the impacts of EU urban initiatives, and previous evaluative assessments of similar place-based initiatives, this chapter proposes the use of ‘controlled comparisons’ to perform this crucial task for the urban dimension of the European Cohesion Policy: analyses should compare changes before and after interventions between territorial targets and appropriate contrafactual. Previous studies on policy effectiveness have analysed programme outcomes or case studies, but their results do not provide information about initiatives’ impacts due to the lack of contrafactual comparison. Besides, urban initiatives establish some ‘eligibility criteria’ to select their territorial targets. Therefore, contrafactual should be chosen according to the criteria. Based on these ideas, this chapter applies propensity score matching to select appropriate experimental and control groups to evaluate the impact of EU urban initiatives in Spain. The following chapters use the chosen neighbourhoods (experimental and control groups) to perform impact analyses using different methodological approaches.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Urban policy

- Impact evaluation

- Neighbourhoods

- Controlled comparison

- Quasi-experimental design

- Propensity scores

- European Union

Introduction

As indicated in the introductory chapter (Chapter 1), sustainable and integrated urban development strategies promoted in the EU should have two central add values: on the one hand, demonstrative effects regarding improvements in the design and implementation of urban policies; on the other hand, to improve the cohesion of the territorial areas where they are applied, specifically urban areas (neighbourhoods) in the case at hand. However, whereas the first objective has been the subject of analysis, studies on the second objective are almost non-existent.

Over the coming chapters, some evidence on this issue will be presented. These chapters try to provide policy evidence about the impact of integrated urban development strategies on different aspects of quality of life and the scale of territories targeted by programmes. Previously, in the first section of this chapter, we will briefly review the strategies commonly used to analyse the effects of these types of initiatives and their scope. In the second section, we will present the general approach we have used to analyse the impact of the URBAN and URBANA initiatives as examples of integrated urban strategies promoted by the EU.

Analysing the Effects of Integrated Urban Development Strategies on Socio-Spatial Cohesion: Main Methodological Strategies

The analyses of the effects of integrated urban development programmes promoted by the EU on socio-spatial cohesion have mainly utilised two strategies: intensive—in-deep—analysis of specific projects or the analysis of programme perspective. The first approach involves analysing projects as case studies or comparing cases to yield conclusions regarding demonstrative effects (lessons learned) for other cases or applications. These studies provide detailed evidence about project design and, particularly, the implementation process and results (outcomes) according to the objectives set. Their most relevant contribution has been demonstrating what integrated strategy development entails and the elements that facilitate or inhibit its implementation. This approach is applied, for example, in the URBACT networks, the Urban Development Network, and specific studies carried out in Spain (De Gregorio, 2015).

The second perspective has focussed on extensive analysis of the implementation and outcomes in projects applied under a programme—or a programming period. Two main strategies are used for this purpose: the study of implementation and objectives achievement indicators or the consultation processes with experts and stakeholders involved. Regarding the first strategy, implementation analysis has focussed mainly on the level of spending execution or the study of some established indicators of objectives achievement. Good examples of this perspective are the ex-post evaluations made about URBAN initiatives and the urban initiatives implemented in the 2007–2013 programming period (European Commission, 2003, 2010, 2016). However, in their final reports (‘closing reports’), not all projects state the value achieved for the indicators, making it difficult to analyse the programmes as a whole. Moreover, given the bottom-up logic of their design, in many cases, the establishment of achievement levels might not be very realistic, as evidenced by the ex-post evaluation of initiatives developed between 2007 and 2013, including the URBANA Initiative (European Commission, 2016).

For example, in the case of Spain, the ‘closing evaluative reports’ for the URBAN projects provide fairly detailed information, with specific indicators that are quite similar between projects, as well as measurements of their expected and eventually achieved levels. This detail, however, does not appear in the closing reports of the URBANA Initiative. Using the information provided by the former, we have calculated the ‘performance’ level of each policy action included in local projects, comparing the value assigned as the objective to be achieved with the value actually achieved. Of the set of interventions analysed, slightly less than half obtained values greater than 100% and almost half of these values were greater than 150%.Footnote 1

The strategy based on consulting experts and stakeholders often provides information about the strategy developed, as well as factors that have facilitated—or inhibited—its implementation and the achievement of objectives. Thus, for example, in the ex-post evaluation of the URBAN I Initiative, the experts indicated that, in Spain, 100% of the projects had positive effects on the neighbourhood’s urban environment or socio-economic conditions (European Commission, 2003). This report also includes several ideas about factors enhancing or eroding the programme implementation and its success. The ex-post evaluation for the 2007–2013 period also includes a survey among stakeholders providing information about strategies and their success.

In some cases, evaluation based on experts and stakeholders is done through specific assessment protocols in order to provide a comparative assessment. In this regard, the EU has promoted the Territorial Impact Assessment approach. This approach is based on a participatory process of experts and stakeholders to provide a ‘theory’ about the potential territorial effects of EU policies (programmes, initiatives, regulations,…). This ‘theory’ is applied to existing statistical data to catch the territorial heterogeneity before policy implementation and provide a set of potential outcomes according to the ‘theory’ elaborated by experts and stakeholders. The main idea is to show the potential heterogeneous impacts of EU initiatives across European territories (regions, cities, …) This approach has not been applied to the territorial targets of EU urban initiatives (cities or neighbourhoods).Footnote 2 Nevertheless, some exercises have used this approach to check the potential effects of the Territorial Agenda 2030 on cities or the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Dallhammer et al., 2018; Gaugitsch et al., 2020).

Overall, both intensive case studies and the programme analysis perspective have shown the value of EU-integrated urban strategy for urban policy formulation and implementation. However, these approaches do not provide policy evidence of impact because these perspectives only analyse implemented projects without comparisons with other urban areas where EU urban integrated strategies are not implemented (Table 7.1).

This lack of comparison makes it difficult to provide evidence about their impacts because other factors could also explain outcomes and changes in areas targeted by integral strategies. For instance, changes observed in targeted areas can be similar to more general trajectories of change in the urban area in which projects are implemented (the city, the region,..); improvements observed could be caused by sectoral policies that are applied simultaneously across municipalities or neighbourhoods, or observed outcomes could depend on the initial situation in targeted urban areas before project implementation, as the TIA approach sustains.

Thus, these strategies face two methodological challenges: limits to generalisation (or external validity) and limits to explanatory capacity (or internal validity). First is the external validity challenge when dealing with unique case studies, comparative cases without an explicit sample framework explaining controlled factors included in the analyses or the programme establishing specific selection criteria for targeted territories. These criteria mean a ‘policy selection bias’; selected urban areas do not represent all the urban reality in Europe, a state member or a region, only those types targeted by the policy frame. For instance, the focus on vulnerable neighbourhoods in big cities in early EU urban initiatives in the 1990s provided relevant information and results that could be not valid for small and medium-sized cities. Therefore, observed outcomes, changes, or improvements in socio-spatial cohesion will be valid for other cases and contexts. Second is the internal validity challenge due to their ability to show that programmes and projects generate the desired changes in targeted territories, since they do not ‘isolate’ (control) the effect of other potential explanatory factors. Are we sure integrated strategies are the explanatory factor of socio-spatial cohesion improvements in targeted territories?

In this regard, the commonly used strategy to try to overcome these challenges is to establish ‘controlled comparisons’ between places where the programme is implemented and places without this implementation that were ‘similar’ to them before programme implementation. Then, policy impact is analysed as the differences between their respective trajectories of change between pre- and post-implementation periods (Rossi, 1999). This strategy involves comparing urban areas that, firstly, are differentiated by whether they have been the object of intervention or not, and secondly, are similar in aspects that might explain the change between the moments before and after implementation. This approach faces at least three challenges: delimiting the territorial spaces to be compared, defining which conditions make the areas comparable in terms of their ‘starting conditions’ before implementation, and establishing a methodological strategy to ensure this, to ensure this similarity before implementation.

The first of these challenges requires projects to define in some detail the urban area in which it is applied. Albeit unevenly, the URBAN and URBANA projects analysed include some description of the urban area subject to intervention, either in the form of an illustration, a list of affected streets, or a map to identify the census sections it comprises. However, other urban areas where projects have not been implemented should be defined in the same cities where projects have been implemented. These should be similar to the previous ones before project implementation. This issue relates to the next challenge.

The second challenge concerns the need to establish how the urban areas should be similar, in other words, the ‘starting conditions’ that should be controlled. At least two approaches can be considered in this regard: a theoretical approach or a policy-applied approach. The first approach means similarity is established according to prior knowledge about causes explaining changes in urban areas that could be included or not in the policy theory of the programme. The second approach is based on the policy theory established, implicitly or explicitly, by the programme in its policy frame, regardless of other theoretical knowledge about urban change not included in the programme's policy. The policy frame sets goals, implementation preferences, and criteria for territorial targets. These eligibility criteria could mean targeted territories could have specific and differentiated traits from other urban areas.

The programmes analysed here define their territorial targets as areas with high levels of socio-spatial vulnerability within the framework of their respective urban contexts (cities), establishing a series of problems that must be evidenced in the diagnosis of the projects to show their eligibility. These criteria respond to the logic of their policy frame based on the idea of integrated urban regeneration promoted by the EU since the 1990s. The programmes aim to reduce processes of socio-spatial segregation by bringing these urban spaces closer to the general dynamics of their cities. To this end, they ‘add’ a specific integrated policy strategy to the existing sectoral policies actions in the urban area where they act. The main assumption is that these targeted actions will close the gaps between target areas and other urban areas. Therefore, to be successful, programmes must select areas with high socio-spatial vulnerability appropriate to this policy frame (Rae, 2011; Thomson, 2008). Thus, the impact analysis must compare urban areas chosen by the projects with similar areas according to the eligibility criteria established by the programme, the ‘starting conditions’, which, accordingly, justify their implementation and potential effects in selected urban areas. This ‘applied policy approach’ is the strategy we will use here.

The third challenge concerns the methodological strategy used to establish and ensure the similarity in the starting conditions among urban areas that will be compared. We have used propensity score matching, as other evaluative exercises have done for similar area-based initiatives in other regions (Bondonio & Greenbaum, 2007; Ploegmakers & Beckers, 2015) and to analyse the impact of Cohesion Policy at the regional level (Dall'Erba & Fang, 2017). This method allows us to select similar urban areas, in terms of their likelihood of being chosen as the territorial target of the programmes, to the areas eventually chosen to implement the projects, as we will explain below.

Impact Analysis Using Controlled Comparisons: A Quasi-Experimental Research Design Approach

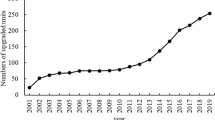

Based on the criteria indicated in the previous section, this section presents the general strategy used to analyse the impact of EU-driven integrated urban development programmes in Spain between 1994 and 2013 (the URBAN and URBANA initiatives). We will consider only URBAN I projects, as URBAN II was implemented in only ten cities, which is too small a sample for controlled comparison analyses. We will detail the strategy used in the context of the three challenges mentioned above.

Observation Units: ‘Homogeneous Urban Areas’

The urban area in which each project was developed has been delimitated as groupings of census sections based on the illustration, description, or map included in each project documentation. For the rest of the areas in each of the cities that participated in the URBAN I and URBANA Initiatives, homogeneous urban areas (HUAs) have been defined by applying four criteria. Firstly, they were similar to the selected areas in their resident population, an eligibility criterion included in URBAN but not in URBANA projects. Secondly, given the approach adopted in their policy frame, they were internally homogeneous regarding socio-spatial vulnerability. Thirdly, they did not include major urban discontinuities due to large avenues, train rails, roads, etc. And fourthly, they would allow adequate estimates based on the 2011 Population Census samples. As regards the second criterion, we used a synthetic indicator of socio-spatial vulnerability validated at the census tract level in 1991 and 2001, which includes four sub-indicators: housing in poor conditions, unemployment rate, uneducated population, and percentage of unskilled workers (Fernández et al., 2018).

The HUAs were defined for 2001, and the same territorial areas were delimited for 1991 and 2011. Therefore, these are similar territorial urban areas spaces enabling their comparison over time. In the case of the URBAN I programme, 542 urban areas were defined for a set of 26 cities, since in three of the cities that implemented this programme was no geo-referencing of their census sections for the year 1991 (Langreo, Castellón, and Avilés). For the URBANA programme, 576 areas in 43 cities were identified (in the case of Coslada there is no documentation on its project).Footnote 3

The targeted areas defined by the projects are extensive. Therefore, the delimitated homogeneous urban areas are also vast. This large size might dilute evidence of the impact of projects. First, the policy actions could be carried out in specific spaces of the selected urban area as a whole, and, therefore, they affect such spaces or only some of the area’s residents to a greater extent. Second, some heterogeneity could exist between different spaces included in targeted areas (in their urban fabric, social composition, or other specific aspects), meaning that the whole area is not exactly equal in terms of its starting conditions. However, our study is not about the change in urban areas, but about the impact of the programme. We have studied the design and development of the projects, trying to stick as closely as possible to the urban areas as defined in them. That is to say, our analysis is about the change promoted by integrated strategies promoted by the EU in their targeted territories, not about general processes of urban change.

Reducing the ‘Selection Bias’ of the Programmes: Propensity Score Matching for Experimental and Control Areas Selection

As indicated above, the urban areas selected by the projects should present high levels of socio-spatial vulnerability according to the eligibility criteria established by the programmes. These mainly include urban fabric degradation, bad environmental quality, low levels of economic activity, and high levels of social exclusion, especially unemployment; although URBAN II also includes other aspects regarding educational achievement or specific problems linked to intercultural relations and security in neighbourhoods (European Commission, 1994, 2000; Ministry of Public Administration, 2007; Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2007). Except for environmental quality, for which there is no information at the census section level for either 1991 or 2001, we have elaborated specific indicators to measure these eligibility conditions: population density, percentage of housing in good condition, the density of establishments that develop economic activity (per thousand inhabitants), and the rate of employment. In the URBANA Initiative, we have also considered the percentage of the population without any formal education title since problems related to educational achievement and the level of academic training of its residents are explicitly included in the eligibility criteria.

The comparison between selected and non-selected areas shows that the former are more vulnerable, especially regarding house conditions and unemployment (Table 7.2). Although the differences are not statistically significant, they also have higher demographic density and business density, which would not correspond to the established criteria. This might be explained because selected areas included historical centres of cities which concentrate on economic activities—because of their centrality in the urban space—although they present a considerable level of socio-spatial vulnerability according to urban environment conditions or social composition (Fernández Salinas, 1994).

These differences would show that the selection of territorial targets within the programmes was adequate since they are urban areas with high levels of socio-spatial vulnerability.Footnote 4 However, this implies the existence of a ‘selection bias’ that would affect the impact analysis of jointly analysing all these urban areas (selected and unselected). In other words, we would be comparing areas based on different starting conditions making it difficult to establish whether changes were due to the implementation of a project or to these initial differences.

We applied the propensity score matching method to ensure comparisons between urban areas with similar starting conditions. This method ‘matches’ selected areas with non-selected urban areas according to their similarity in terms of the eligibility criteria established by the programmes. First, a logistic regression model is used to estimate the probability that an urban area would have been selected. The dependent variable is whether an urban area has been the object of intervention or not (selected vs. non-selected UHAs), and the indicators that measure the eligibility criteria of each programme are included as covariables. Second, urban areas with similar propensity scores (similar odds of being chosen) are ‘matched’. There are different matching methods. We have applied the nearest-neighbourhood method matching each selected area by the programme with the closest one according to the propensity score. In addition, we applied more specifications. First, the experimental and control groups only include urban areas in the ‘common support’ area (overlap between the propensity score distributions of selected and non-selected HUAs). Second, up to five non-selected areas have been chosen for each area included in the experimental group. Although this specification might be less effective in reducing selection bias, it improves the accuracy of impact estimates (Ming & Rosenbaum, 2000). Finally, we have applied three callipers: levels of standard deviation values equal to 0.0, 0.1, and 0.2 of the logit function of the propensity score have been set.

To validate the propensity score models, we analysed the balance in the distribution of the propensity score and covariables within matched urban areas, including areas selected by the programme, which would constitute our experimental group, and those not selected by the programme, which would make up our control group. We compared the standardised differences between experimental and control groups to ensure they do not exceed 25% and that the overall RMI L1 indicator is small after matching. In addition, we replicated the logistic regression model to verify that its fit-level (Pseudo-R2) is lower in the model that includes matched areas than in the original (including all urban areas). These analyses show all models are well balanced, both globally and for covariables, with a lower fit for the regression model with the paired areas (Table 7.3)Footnote 5.

Analysis of the ‘Average’ Impact of Programmes and Potential Heterogeneous Effects: Controlled Comparisons of Urban Trajectories of Change and Other Possible Specifications

To analyse the impact of the URBAN and URBANA Initiatives, we will compare the trajectories of change in the experimental and control groups between pre and post-implementation periods. The difference between their trajectories will inform us of the impact of the programmes. To perform this analysis, we have used existing secondary data sources. This will limit the analysis we will be able to carry out, but it will also show that, within these limits, it is possible to analyse the impact of urban integrated strategies promoted by the EU.

The following chapters provide policy evidence in this regard. They should also be taken as exercises that seek to show different strategies for making controlled comparisons from existing data sources to analyse the impact of EU-integrated strategies. The first chapter applies repeat measures analysis between pre- and post-intervention times based on ecological information (secondary data aggregated at the neighbourhood—urban area—level) to analyse URBAN policy impacts regarding some of their objectives (Chapter 8). The second study trends of change in experimental and control areas by analysing individual cross-sectional data for periods before and after URBANA Initiative implementation (Chapter 9). The third applies repeat measures models with ecological measurements at three points in time to study the short-time and long-time impacts of the URBAN Initiative on the cultural amenities in neighbourhoods (Chapter 10). And finally, we will contextualise the trajectories of change in experimental areas within the urban context of their respective cities applying a comparative case analysis (Chapter 11). In all cases where we analyse the impact based on propensity score matching, we will present the results with the models that use a calliper width equal to 0.2, as this will provide the best results for the estimates (Austin, 2010; Yongji et al., 2013).

As regards the general policy theory behind sustainable and integrated strategies implemented by URBAN and URBANA Initiatives (Chapter 6), two main dimensions or areas of policy impact could be defined; on the one hand, the contextual dimension of targeted urban areas, therefore, improvements that suppose a better opportunity structure for residents. For instance, the urban fabric (better or more houses, public spaces, basic urban services,..) urban mobility opportunities, increasing economic activity and employment opportunities, access to more or new services, environmental quality, low levels of social conflict, crime, … On the other hand, improvements in the ‘individual’ living conditions of residents and their households (socio-economic situation, employment, educational attainment, health status, participation in neighbourhood activities and participatory processes,…). The following chapters will analyse some of these aspects. All these issues could not be examined due to limitations in secondary data disposable and used in the subsequent analyses.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, the analyses done include some of the main goals of the EU cohesion policy and its urban integrated strategies (for instance, habitability, economic activity, employment, or educational attainment).

These analyses will show the ‘average impact’ as differences in the trajectory of change between similar (targeted and non-targeted) urban areas. The results will provide evidence for the following question: what would have happened if the project had not been implemented? This situation is represented by the trajectory of change in the control areas (counterfactual conditional). Comparison with the trajectory of the experimental areas will make it possible to show the impact of the programmes as a whole; in other words, ‘what happens when the project has been implemented’. Therefore, the added value promoted by the urban dimension of the EU cohesion policy through integrated urban development strategies.

This assumes that the analyses will not consider the possible existence of ‘composition effects’ derived from potential diversity between projects, urban areas, or within them not controlled by matching. That is to say, the possible existence of policy heterogeneous effects beyond programme eligibility criteria. For example, according to the specific strategy of each project (its theory), these might include the nature and intensity of residential mobility phenomena or the generational change in neighbourhood residents during the projects implementation period, or specific differences in the starting conditions not included in the eligibility criteria of the programmes (e.g. historic centres vs. peripheral neighbourhoods, or, even, because of the intensity of socio-spatial vulnerability processes). These phenomena can produce opposite effects that, on the whole, blur the evidence of programme impact. Therefore, these elements could also be included in controlled comparisons. Hence, in addition to the selection bias of each programme (matching through propensity score matching), each of the following chapters will add other specific control elements in order to show how possible composition effects could be considered using existing data sources, which are not otherwise considered in the documentation relating to the programmes (and the theory that may arise from them). In other words, we will use propensity score matching based on programmes eligibility criteria (a ‘policy approach’ to ensure similarity between experimental and control groups) plus some theoretical ideas about change in urban areas (a more ‘theoretical approach’) to try to pay attention to potential heterogeneous effects of programmes. Table 7.4 presents the research questions analysed.

Thus, the following chapters provide evidence on the ‘average’ impact of the URBAN and URBANA Initiatives, that is, an initial approach that considers the ‘general policy theory’ of change implied by these programmes. This brings evidence to an area of study, the impact of EU-integrated urban strategies, for which there is not a lot of previous analysis. The following chapters also provide examples of methods that can be used to analyse the impact of integrated urban strategies using data sources that are usually available to the researcher community and agents involved in the programmes or their specific projects. More detailed access to these and other sources, or the production of data specifically oriented towards the analysis of their impact, might refine the results presented below, so they are able to specify, to an even greater degree, ‘controlled comparisons’ that, for example, derive from the specification of the theories behind these programmes and their projects.

Notes

- 1.

There are also differences according to policy sectors and the type of intervention, with higher levels for those that suppose interventions on the urban space, and lower levels for those referring to welfare and social integration.

- 2.

About the TIA approach and the on-line tool designed in the framework of ESPON: https://apps.espon.eu/TiaToolv2/welcome. About other models based on the TIA approach Medeiros (2020).

- 3.

The homogeneity of delimitated urban areas according to population size, population density, and socio-economic vulnerability has been analysed to validate them. Comparisons with other territorial delimitations (census districts and sub-municipal areas defined under the URBAN AUDIT programme) have also been made to validate this issue. More details in Fernández-García (2021).

- 4.

We have also found that the differences between selected and unselected areas exist when considering the urban context, the city, in which they are located using measurements centred on city averages (Fernández-García et al., 2021).

- 5.

- 6.

For instance, not specific data about environmental quality exist at the census track level. Therefore, this goal can not be analysed.

References

Austin, P. C. (2010). Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 10(2), 150–161.

Bondonio, D., & Greenbaum, R. T. (2007). Do local tax incentives affect economic growth? What mean impacts miss in the analysis of enterprise zone policies. Regional Science and URban Economics, 37(1), 121–136.

Dall’erba, S., & Fang, F. (2017). Meta-analysis of the impact of European Union structural funds on regional growth. Regional Studies, 51(6), 822–832.

Dallhammer, E., Schuh, B., & Caldeira, I. (2018). Urban impact assessment report on the implementation of the 2030 agenda. Brussels, ESPON. https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/COTER/TIA-Urban-Agenda-28052018.pdf

De Gregorio, S. (2015). Políticas urbanas de la Unión Europea desde la perspectiva de la planificación colaborativa. Las iniciativas comunitarias Urban y Urban II en España. Cuadernos de Investigación Urbanística, 98.

European Commission. (1994). Notice to the Member States laying down guidelines for operational programmes which Member States are invited to establish in the framework of a community initiative concerning urban areas (Urban), Official Journal of the European Communities, 94/C 180/2. European Union.

European Commission. (2000). Guidelines for a community initiative concerning economic and social regeneration of cities and neighborhoods in crisis in order to promote sustainable urban development (URBAN II), Official Journal of the European Communities, 2000/C 141/04, European Union.

European Commission. (2003). Ex-post evaluation: Urban community initiative. European Union.

European Commission. (2010). Ex-post evaluation of cohesion policy programmes 2000–06: The urban community initiative. European Union.

European Commission. (2016). Ex-post evaluation of urban development and social infrastructures. European Union.

Fernández-García, M., Navarro, C. J., & Gómez-Ramirez, I. (2021). Evaluating territorial targets of european integrated Urban policy. The URBAN and URBANA initiatives in Spain (1994–2013). Land, 10(9), 956.

Fernández, M. (2021). Las políticas de regeneración urbana promovidas por la UE en España. Un análisis comparado del “modelo de oferta” de las iniciativas URBAN y URBANA en diferentes contextos (Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Pablo de Olavide). https://rio.upo.es/xmlui/handle/10433/11703

Fernández, M., Navarro, C. J., Zapata, Á. R., & Mateos, C. (2018). El análisis de la desigualdad urbana. Propuesta y validación de un índice de nivel socio-económico en áreas urbanas españolas (1991–2001). Empiria. Revista De Metodología De Ciencias Sociales, 39, 49–77.

Fernández-Salinas, V. (1994). Los centros históricos en la evolución de la ciudad europea de los años setenta. Eria, 34, 121–131.

Gaugitsch, R., Dallhammer, E., Schuh, B., Hui-Hsiung, C., & Besana, F. (2020). Territorial impact assessment: The state of the cities and regions in the COVID-19 crisis. Brussels, European Union. https://cor.europa.eu/en/engage/studies/Documents/TIA-Covid19.pdf

Luellen, J. K., Sadish, W. R., & Clark, M. H. (2005). Propensity scores: An introduction and experimental test. Evaluation Review, 29(6), 530–558.

Medeiros, E. (Ed.). (2020). Territorial impact assessment. Springer.

Ming, K., & Rosenbaum, P. R. (2000). Substantial gains in bias reduction from matching with a variable number of controls. Biometrics, 56, 118–124.

Ministerio de Administraciones Públicas. (2007). Resolución de 7 de noviembre de 2007, de la Secretaría de Estado de Cooperación Territorial por la que se aprueban las bases reguladoras de la convocatoria 2007 de ayudas del Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional para cofinanciar proyectos de desarrollo local y urbano durante el periodo de intervención 2007–2013. Ministerio de Administraciones Públicas, Gobierno de España.

Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda. (2007). Iniciativa URBANA (URBAN). Orientaciones para la elaboración de propuestas. Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Gobierno de España.

Ploegmakers, H., & Beckers, P. (2015). Evaluating urban regeneration: An assessment of the effectiveness of physical regeneration initiatives on run-down industrial sites in the Netherlands. Urban Studies, 52(12), 2151–2169.

Rae, A. (2011). Learning from the past? A review of approaches to spatial targeting in urban policy. Planning Theory & Practice, 12(3), 331–348.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55.

Rossi, P. H. (1999). Evaluating community development programs: Problems and prospects. In R. F. Ferguson & W. T. Dickens (Eds.), Urban problems and community development (pp. 521–568). The Brookings Institution.

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science, 25(1), 1–29.

Thomson, D. E. (2008). A dose of realism for healthy urban policy: Lessons from area-based initiatives in UK. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 60, 108–115.

Yongji, W., Hongwei, C., Chanjuan, L., Zhiwei, J., Ling, W., Jiugang, S., & Jielai, X. (2013). Optimal Caliper width for propensity score matching of three treatment groups: A Monte Carlo study. PLoS ONE, 8(12), e81045.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Domínguez-González, A., Navarro Yáñez, C.J. (2023). The Impact of EU-Integrated Urban Development Initiatives: Research Strategies Beyond ‘Good Practices’. In: Navarro Yáñez, C.J., Rodríguez-García, M.J., Guerrero-Mayo, M.J. (eds) EU Integrated Urban Initiatives. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20885-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20885-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-20884-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-20885-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)