Abstract

This chapter presents key concepts and theories relevant to the self-management of chronic disease. It starts by defining health behaviours and establishes the distinction between health behaviours and determinants of behaviours. Next, we present a brief description of key behaviour change theories and models relevant to the self-management of chronic disease. The COM-B model of behaviour change is then detailed, with an illustration of how it applies to sustained health behaviour changes in the context of self-management of chronic disease.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Chronic diseases

- Self-management

- Health behaviours

- Health determinants

- Behaviour change

- Behaviour change models and theories

This chapter contributes to achieving the following learning outcomes:

-

BC1.1 Differentiate between health behaviour and behaviour determinants.

-

BC2.1 Describe the approach of different models and theories to behaviour change in health.

-

BC2.2 Provide a rationale for using behaviour change models/theories.

-

BC2.3 Explain how different models and theories predict self-management behaviours in chronic disease and allow an understanding of interventions that can change these behaviours.

Population ageing and the increasing burden of chronic diseases require the health system to support self-management (Araújo-Soares et al., 2019). Many have argued that behaviour change support is central to the needs of persons with chronic diseases. Although modifiable health behaviours are recognised as a major influence in the management of chronic conditions, there are several barriers to effective behaviour change support by health and other professionals, such as compartmentalisation in silos of healthcare provision, lapses in communication between different teams and lack of training (Vallis et al., 2019).

Ultimately, to meet the real needs of persons living with chronic diseases, professionals need education fostering the development of behaviour change competencies, as described by the interprofessional competency framework presented in Chap. 1. In particular, health and other professionals need to acquire concepts and definitions from behavioural science, to better understand how to support people living with chronic diseases.

In this chapter, we address the concepts of health behaviours, the difference in relation to behaviour determinants and, briefly, key behaviour change models and theories that can inform self-management interventions in chronic disease.

2.1 Health Behaviours and Behaviour Determinants

Chronic diseases are the result of the interplay between genetic, physiological, environmental and behaviour determinants. This means that health-related decisions that people make will impact on their health outcomes. Some have even argued that, in the case of chronic conditions, health outcomes are more influenced by the choices the individual makes than by the care directly provided by health professionals (Vallis et al., 2019).

The interest in behaviours that have an impact on health and well-being is shaped, particularly, by the assumption that such behaviours are modifiable (Conner, 2002). Health behaviour has been defined in various ways, as illustrated in Table 2.1.

As opposed to acute conditions, in chronic diseases the role of health and other professionals is more focused on supporting and empowering persons to adopt and maintain behaviours, such as medication adherence, not smoking, keeping a healthy weight, being physically active, consuming substances in moderation, eating healthily and getting adequate sleep. It has long been recognised that these health-protective behaviours have a significant impact in preventing both morbidity and mortality, also impacting “(...) upon individuals’ quality of life, by delaying the onset of chronic disease and extending active lifespan” (Conner, 2002). More recently, a European multicohort study in 116,043 people free of major chronic diseases at baseline, from 1991 to 2006, suggests that various healthy lifestyle profiles, such as regular physical activity, BMI less than 25, not smoking and moderate alcohol consumption, appear to yield gains in life-years without major chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Nyberg et al., 2020).

It is therefore important to distinguish between health-impairing (or health-risk) and health-enhancing (or health-protective) behaviours:

“Health impairing behaviours have harmful effects on health or otherwise predispose individuals to disease. Such behaviours include smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and high dietary fat consumption. In contrast, engagement in health enhancing behaviours convey health benefits or otherwise protect individuals from disease. Such behaviours include exercise, fruit and vegetable consumption, and condom use in response to the threat of sexually transmitted diseases.” (Conner, 2002)

Table 2.2 depicts examples of health outcomes associated with the core health-risk behaviours; as already pointed out, these outcomes may be influenced by other factors than individual behaviours per se, such as genetics or environmental issues.

Behaviour determinants are factors that influence the behaviour, either in a positive or in a negative way, i.e. facilitators of and barriers to the performance of the behaviour, respectively. These determinants can be individual, such as biological/demographic (i.e. age, health history) and psychological factors (i.e. motivation, humour, previous experiences), or non-individual, such as aspects related to the behaviour itself (i.e. time needed to see changes), environmental/social issues (i.e. interpersonal relationships, such as social support) and health policies (i.e. policies targeting the health problem and making it easier/harder to change).

In fact, behaviour determinants can be categorised in a multitude of ways, one of which is a widely used model of behaviour change – the COM-B model (Michie et al., 2011, 2014a) – which will be further described in this chapter. This model groups determinants into three major categories: capability (physical and psychological), motivation (reflexive and automatic) and opportunity (social and physical) (Michie et al., 2011, 2014a).

Due to the complexity of health-related human behaviour, for which usually various determinants are responsible for the adoption and sustainability of the behaviours, behavioural science has dedicated much of its research to the development, testing and refinement of models and theories that aim to explain, predict, model and change behaviour. These are described in the next section.

2.2 Behaviour Change Theories and Models

There are various definitions of theories. In behavioural science, a theory has been defined as “a set of concepts and/or statements which specify how phenomena relate to each other, providing an organising description of a system that accounts for what is known, and explains and predicts phenomena” (Davis et al., 2015, p. 327). In brief, theories are a systematic way of understanding phenomena (e.g. health behaviour(s)), in which a set of concepts and variables (e.g. determinants of behaviours such as motivation, self-efficacy and social influences) and prepositions about their relationships are established (Glanz et al., 2002).

In the context of health behaviour change, theories “(...) seek to explain why, when, and how a behaviour does or does not occur, and to identify sources of influence to be targeted in order to alter behaviour” (Michie et al., 2018, p. 70). They are important to understand disease patterns and to explain why individuals and communities have certain behaviours (Simpson, 2015), as well as to support clinical practice and professionals in day-to-day interventions. Using a theory when developing and evaluating interventions allows the identification of what needs to change (i.e. the determinants of the behaviour), the barriers and facilitators to changing those influences and the identification of mechanisms of action that operate along the pathway to change. Further, many theories identify ways in which the behaviour determinants can be modified, i.e. which techniques can be implemented in interventions to, for instance, increase motivation, increase the capability to perform the behaviour and form habits.

There is therefore consensus that health behaviour change interventions should be informed by theory. For example, the UK’s Medical Research Council recommends the identification of relevant theories for designing complex interventions (Skivington et al., 2021), as does the US Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health (Rimer & Glanz, 2005). Guideline PH49 from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on individual-level health behaviour change interventions recommends that staff should be offered professional development on behaviour change theories, methods and skills (NICE, 2014).

There are many theories of behaviour and behaviour change; a multidisciplinary literature review has identified 83 theories containing a total of 1725 concepts (Davis et al., 2015). A summary of these theories, their concepts and relationships are available in a theory database (Hale et al., 2020).

We present an overview of the main theories that have been applied to self-management of chronic diseases. Table 2.3 presents a brief description and key references for key social-cognitive, motivation and integrative theories (see Michie et al., 2014b, for more details about these theories). Examples of applications are presented in accompanying papers.

2.3 COM-B Model: A Model to Guide Interventions

Given the multiplicity of theories of behaviour that exist and the need for a simplified model to support the design of behaviour change interventions, Michie and colleagues developed the COM-B model (Michie et al., 2011), which defines behaviour as a result of the individual’s capability, opportunity and motivation to follow a certain course of action. Capability is an attribute of a person that reflects the psychological and physical abilities to perform a behaviour, including knowledge and skills. Motivation is an aggregate of mental processes that energise and direct behaviour; it involves the automatic and reflective motivation, such as the individual’s goals, plans and beliefs and their emotions, habits or impulses, respectively. Opportunity is an attribute of an environmental system, corresponding to the external factors that may facilitate or make it harder for an individual to adopt a specific behaviour, such as the physical and social environment (Michie et al., 2011; West & Michie, 2020). Table 2.4 presents definitions of the COM-B components (West & Michie, 2020).

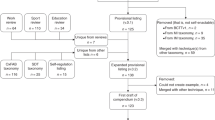

Illustration of the COM-B model (West & Michie, 2020)

For particular behaviours, people, context or phase of the behaviour change process, certain barriers or facilitators will have more influence than the others. The analyses of these determinants play a crucial role in selecting which strategies will work better to achieve the desired behaviour, as described in Chap. 4.

This model has been successfully used in designing behaviour change interventions (e.g. Issac et al., 2021; Wheeler et al., 2018), to support behaviour change in practice. We present an example related to behaviour change in the self-management of a chronic disease. Wheeler et al. (2018) researched the feasibility and usability of a mobile intervention for persons with hypertension, using the COM-B model as a framework for the development of a knowledge model to support the intervention. Knowing that each person has a behaviour source that relies on different factors, the intervention was tailored to the user’s individual profile, based on the initial contact. Using the COM-B model, the authors identified different profiles via a self-evaluation questionnaire on determinants for sodium intake and physical activity. Examples of these determinants are synthesised in Table 2.5, based on Wheeler et al. (2018).

As depicted in Fig. 2.1, according to this model, all three categories of determinants influence the adoption and maintenance of health-protective behaviours, and consequently the successful self-management of chronic diseases.

Key Points

-

A health behaviour is any behaviour that can affect a person’s health either by enhancing it (health-protective behaviour) or impairing it (health-damaging or health-risk behaviour).

-

Behaviour determinants are individual or non-individual aspects which can influence the behaviour either in a positive or a negative way, i.e. barriers or facilitators for the adoption of the behaviour.

-

Theories and models of behaviour change provide a deeper understanding about behaviour patterns, responses and their determinants; they can guide effective behaviour change support.

-

The COM-B model presents an integrative approach, in which a behaviour is considered to be influenced by physical and psychological capability, reflective and automatic motivation and physical and social opportunity.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Araújo-Soares, V., et al. (2019). Developing behavior change interventions for self-Management in Chronic Illness: An integrative overview. European Psychologist, 24, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000330

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. The American Psychologist, 37, 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of T ought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality-social, clinical and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.1.111

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of behaviour. Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Y., Tan, D., Xu, Y., Wang, B., Li, X., Cai, X., Li, M., Tang, C., Wu, Y., Shu, W., Zhang, G., Huang, J., Zhang, Y., Yan, Y., Liang, X., & Yu, S. (2020). Effects of a HAPA-based multicomponent intervention to improve self-management precursors of older adults with tuberculosis: A community-based randomised controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(2), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.09.007

Conner, M. (2002). Health behaviors. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.14154-6.

Conner, M. (2010). Cognitive determinants of health behavior. In A. Steptoe (Ed.), Handbook of behavioral medicine (pp. 19–30). Springer Science and Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09488-5_2

Conner, M., & Norman, P. (Eds.). (1996). Predicting health behaviour. Open University Press.

Davis, R., Campbell, R., Hildon, Z., Hobbs, L., & Michie, S. (2015). Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 323.44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.941722

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. Plenum Publishing.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B., & Lewis, F. (2002). Health behavior and health education. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B., & Viswanath, K. (Eds.). (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Gochman, D. (1997). Health behavior research: Definitions and diversity. In D. Gochman (Ed.), Handbook of health behavior research (Vol. I), personal and social determinants. Plenum Press.

Hale, J., Hastings, J., West, R., Lefevre, C. E., Direito, A., Connell Bohlen, L., Godinho, C., Anderson, N., Zink, S., Goarke, H., & Michie, S. (2020). An ontology-based modelling system (OBMS) for representing behaviour change theories applied to 76 theories [version 1; peer review: Awaiting peer review]. Wellcome Open Research.

Issac, H., Taylor, M., Moloney, C., & Lea, J. (2021). Exploring factors contributing to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) guideline non-adherence and potential solutions in the emergency department: Interdisciplinary staff perspective. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 14, 767–785. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S276702

Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818401100101

Jiang, L., Liu, S., Li, H., Xie, L., & Jiang, Y. (2021). The role of health beliefs in affecting patients’ chronic diabetic complication screening: A path analysis based on the health belief model. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30, 2948–2959. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15802

Michie, S., van Stralen, M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014a). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. Silverback Publishing.

Michie, S., Campbell, R., Brown, J., West, R., & Gainforth, H. (2014b). ABC of behaviour change theories. Silverback Publishing.

Michie, M., Marques, M., Norris, E., & Johnston, M. (2018). Theories and interventions in health behavior change. In T. Revenson & R. Gurung (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315167534

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014). NICE Guidance: Behaviour change: individual approaches. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49

Ntoumanis, N., Ng, J., Prestwich, A., Quested, E., Hancox, J., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E., Ryan, R., Lonsdale, C., & Williams, G. (2021). A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychology Review, 15(2), 214–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529

Nyberg, S. T., Singh-Manoux, A., Pentti, J., Madsen, I. E. H., Sabia, S., Alfredsson, L., et al. (2020). Association of healthy lifestyle with years lived without major chronic diseases. JAMA Internal Medicine, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0618

Parkerson, G., et al. (1993). Disease-specific versus generic measurement of health-related quality of life in insulin dependent diabetic patients. Medical Care, 31, 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199307000-00005

Prestwich, A., Conner, M., Hurling, R., Ayres, K., & Morris, B. (2016). An experimental test of control theory-based interventions for physical activity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 21(4), 812–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12198

Rich, A., Brandes, K., Mullan, B., & Hagger, M. S. (2015). Theory of planned behavior and adherence in chronic illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(4), 673–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9644-3

Rimer, B. K., & Glanz, K. (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

Romeo, A. V., Edney, S. M., Plotnikoff, R. C., et al. (2021). Examining social-cognitive theory constructs as mediators of behaviour change in the active team smartphone physical activity program: A mediation analysis. BMC Public Health, 21, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10100-0

Rosenstock, I. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200403

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publishing.

Schwarzer, R. (1992). Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviours: Theoretical approaches and a new model. In R. Schwarzer (Ed.), Self-efficacy: Thought control of action (pp. 217–243). Hemisphere.

Senkowski, V., Gannon, C., & Branscum, P. (2019). Behavior change techniques used in theory of planned behavior physical activity interventions among older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 27(5), 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2018-0103

Simpson, V. (2015). Models and theories to support health behavior intervention and program planning. Available from: https://extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/HHS/HHS-792-W.pdf

Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

Teixeira, P. J., Marques, M. M., Silva, M. N., Brunet, J., Duda, J. L., Haerens, L., La Guardia, J., Lindwall, M., Lonsdale, C., Markland, D., Michie, S., Moller, A. C., Ntoumanis, N., Patrick, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., Sebire, S. J., Standage, M., Vansteenkiste, M., et al. (2020). A classification of motivation and behavior change techniques used in self-determination theory-based interventions in health contexts. Motivation Science, 6(4), 438–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000172

Tougas, M., Hayden, J., McGrath, P., Huguet, A., & Rozario, S. (2015). A systematic review exploring the social cognitive theory of self-regulation as a framework for chronic health condition interventions. PLoS One, 10(8), e0134977. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134977

Vallis, M., et al. (2019). Integrating behaviour change counselling into chronic disease management: A square peg in a round hole? A system-level exploration in primary health care. Public Health, 175, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.06.009

West, R., & Michie, S. (2020). A brief introduction to the COM-B model of behaviour and the PRIME theory of motivation. Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/WW04E6

West, R., Godinho, C. A., Bohlen, L. C., Carey, R. N., Hastings, J., Lefevre, C. E., & Michie, S. (2019). Development of a formal system for representing behaviour-change theories. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(5), 526. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0561-2

West, R., Michie, S., Rubin, J., & Amlôt, R. (2020). Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9

Wheeler, T., Vallis, T., Giacomantonio, N., & Abidi, S. (2018). Feasibility and usability of an ontology-based mobile intervention for patients with hypertension. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.08.002

Zhang, C., Zhang, R., Schwarzer, R., & Hagger, M. S. (2019). A meta-analysis of the health action process approach. Health Psychology, 38, 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000728

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Henriques, M.A., de Sousa Loura, D. (2023). Concepts and Theories in Behaviour Change to Support Chronic Disease Self-Management. In: Guerreiro, M.P., Brito Félix, I., Moreira Marques, M. (eds) A Practical Guide on Behaviour Change Support for Self-Managing Chronic Disease. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20010-6_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20010-6_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-20009-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-20010-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)