Abstract

The first birth is a major life event for all involved parties: woman, partner (and couple). This chapter will address the relevant elements that together shape parenthood and couplehood. That process is somewhat different for the average woman and the average man. Many men more or less tend to return to their pre-pregnancy level of sexual desire rather quickly. On the other hand, many women need much more time before having consolidated in their new role as mothers, simultaneously reconsidering their role as sexual partners. The woman’s physical and sexual system has been adapted by the pregnancy, birth and hormonal changes, potentially resulting in periods of low or no sexual activity. Especially when breastfeeding, her low oestrogen levels keep the vagina atrophic, and her low androgen levels keep arousability low. Together those factors create a substantial risk of developing dyspareunia. Besides these physical aspects, the woman and her partner undergo great psychological adaptations in the post-partum period. This chapter will address how to optimally navigate this phase of ‘transition to parenthood’ and new couplehood.

This chapter is part of ‘Midwifery and Sexuality’, a Springer Nature open-access textbook for midwives and related healthcare professionals.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Post-partum dyspareunia

- Prolactin

- Oestrogen levels

- Transition to parenthood

- Antenatal parenthood education classes

- Vaginal lubrication

1 Introduction

The birth of a baby is, for many, a joyous occasion; however, during the months that follow, significant changes often occur within couples’ relationships. For many couples, during the first 12 months after birth, their intimate relationship transforms, in particular, aspects of their sexual relationship. Couples have reported that extreme tiredness, adapting to new parenting roles, baby care and concern over baby’s wellbeing have impacted their relationship priorities, with their sexual relationship often moving down their list of priorities. While many relationship changes are normative and may be transitory, parents must be advised of the possibility of changes to their intimate and sexual relationships so they are aware and prepared for these should they occur. It is also important that couples are provided with evidence-based, practical information, research-based when possible, on sexual health post-partum, including strategies to maintain a satisfying intimate relationship with their partner during the first year post-partum. This chapter will explore and discuss this multi-dimensional view of sexual health in post-partum and early parenthood (up to 1 year).

2 Post-Partum Sexual Health

This textbook views sexuality and post-partum sexual health as multi-faceted concepts utilising a biopsychosocial approach. Facets include physical dimensions (vaginal lubrication, orgasm and dyspareunia), social dimensions (adapting to parenthood, changed roles), psychological (perception of body image, sexual desire, fear, worry and anxiety) and relational (intimacy, emotional and practical support, perception of sexual desire in the partner and changed roles) dimensions. Yet, an examination of the literature from the last 20 years highlights a predominant focus on the physical facets of post-partum sexual health. Many of the published studies appear to focus on the objective measurement of aspects of sexual health such as sexual desire, dyspareunia, vaginal lubrication, orgasm and timing of resumption of first sexual intercourse after birth and do so through the use of measurement tools, scales and questionnaires. These study reports often use the language of sexual dysfunction and sexual problems when, for example, women indicate that they have not had an orgasm in the preceding 4 weeks or that their sexual desire has lessened since the birth of their baby. This adverse labelling, however, does not take account of the transitional nuances or natural changes that women, and their partners, may experience after childbirth and as they adapt to being parents of a new baby. In more recent years, there is a growing body of evidence, predominately from qualitative enquiry, that has identified and given credence to the multi-dimensional aspects of post-partum sexual health. For example, O’Malley and colleagues emphasise the importance of communication within the couple dyad, communication about tiredness, stress associated with adapting to parenthood, sexual desire or lack of sexual desire as a means of maintaining sexual wellbeing post-birth [1]. How women perceive their body image (and changed body image after birth) has been shown to impact the couple’s sexual wellbeing after birth [2].

3 Intimacy

Intimacy and sexual wellbeing may, for some, be closely aligned, although not necessarily so. In considering sexual wellbeing for couples post-partum, it would be remiss, however, not to consider the concept of intimacy and the role it may play. It is generally recognised that there are four types of intimacy: physical intimacy (e.g. hugs, kisses and sexual activity), emotional intimacy (e.g. closeness, trust and love), cognitive intimacy (e.g. sharing ideas and thoughts) and spiritual intimacy (e.g. bonding over spirituality). Post-partum women have described intimacy as closeness with their partner, a closeness not shared with any other person. Women have described non-sexual touch, such as back rubs, holding hands, cuddles and hugs, as intimacy. They have talked about the importance of sleeping in the same bed, sitting on the same couch, watching a television show together and good morning kisses as aspects of intimacy with their partner. Women have been clear in their narratives that maintaining these non-sexual aspects of intimacy is essential to their sexuality and sexual wellbeing during the first year after birth [1].

Features of satisfying relationships are varied, but commonalities in how couple’s relationships evolve after the first child’s birth have been reported. In a longitudinal study carried out over 8 years with 820 first-time parents, for example, reported factors affecting the quality of the intimate relationship 6 months after the birth of the baby were: coping by adjusting to parental role, mutual support as new parents, the couple’s intimacy (i.e. togetherness and love) and coping by communication (i.e. verbal and non-verbal confirmation) [3], thus supporting the notion that sexual health after birth is multi-dimensional. Furthermore, features associated with long-term relationship satisfaction in couples with children included cohesiveness within the couple, effective communication and maintaining sensuality and sexuality [3, 4]. Sharing parental and household responsibilities, good communication and emotional, physical and sexual intimacy have also been identified as features of a satisfying intimate relationship after the first baby's birth [5].

The following sections will examine some of the common post-partum sexual health issues women and healthcare professionals have identified as important.

4 Resuming Sexual Activity After Birth

Sexual activity is the many ways in which humans express their sexuality, sometimes solo, often together. We also do it through writing, art, music and how we communicate with each other. Common sexual activities include masturbation, vaginal sex, anal sex, oral sex, sex toys, role play (acting out sexual fantasies), deep kissing, intimate massage, etc. Sexual activities enable a vulnerability and deeper level of intimacy that has been shown to lead to greater relationship satisfaction. After birth, a frequent concern for couples is the resumption of any form of sexual activity, particularly when penis-in-vagina penetration may be started. For healthcare professionals (HCPs), this is also a question that does not lend itself to a definitive answer, with many HCPs advising women to resume sexual activity ‘when you feel ready’. Yet, post-partum couples appear to need specific information. For example, many want to know when other couples resume sexual activity or if they ‘have to wait’ until their six-week or final post-partum assessment. As a HCP, being asked these questions can be challenging because each couple is different, and what might be appropriate advice for some couples might not be appropriate for others. Many women report that they wait until they feel physically recovered from the birth, that is, when perineal or abdominal wounds have healed or when lochia has ceased [1]. Some women may wait until uterine afterpains and wound pain have resolved. Regardless of each individualistic scenario, women collectively appear to experience varying levels of fear when they talk about resuming sexual intercourse after birth. They frequently describe a fear of pain (further addressed in Sect. 8.5.1) and a fear of how sexual intercourse will feel. Many wonder if they will experience sexual satisfaction and the feeling of closeness with their partner in the same way as they previously did. Partners also worry about pain, that is, causing their partner pain and when the ‘right’ time is.

Much of the discussion on the timing of resumption of sexual activity after birth is focussed exclusively on vaginal/penile penetration. Reported rates of vaginal/penile penetration resumption range from 41% at 6 weeks [6], 51–65% at 8 weeks [6, 7] and 78% (n = 1020) at 12 weeks after birth [6], although much lower rates have also been reported; for example, 30% (n = 146) in one study at 12 weeks post-partum [8]. Women, however, did tend to resume some form of sexual activity, other than penetrative vaginal sex, earlier in the weeks and months after birth (approximately 10–12% of women), although the exact detail on what types of sexual activities were resumed is generally lacking from studies. Crucially, we are not aware of any studies that have specifically examined sexual health post-partum in women who are in same-sex relationships. Occasionally, a tiny number of women in same-sex relationships have been identified in larger samples of women in opposite-sex relationships with no comparisons made to determine if their experience of their post-partum sexual health differs from opposite-sex couples.

In our own research, involving 21 women in opposite-sex relationships in Ireland up to 2 years post-partum, we explored women’s experience of their sexual health after the birth of their first baby through in-depth one-to-one interviews. Women described how they planned when they would resume vaginal sex. They mentioned the baby being in a different room, being away from the baby and home or the baby having an overnight with immediate family [1]. Women explained that they planned to resume sex after a night out with their partner, for example, going for dinner and drinks. Some women planned to start sexual intercourse as soon as they could post-birth, for example, 4 weeks post-partum. They wanted emotional and physical closeness with their partner. They wanted to feel attractive, feel sexually desired and experience sexual satisfaction. Nonetheless, many other women explained that sexual intercourse was something that took many months to resume. For these women, baby care, infant feeding, adapting to motherhood and the desire for sleep were more important during the first 3 or 4 months after birth. When preparing to resume sexual activity and vaginal penetration, women describe additional considerations: the mode of delivery and the presence of perineal wounds. Some women preferred to wait until they had their final post-partum assessment, traditionally 6 weeks after birth, particularly those who had a caesarean section or operative vaginal birth. Women with perineal stitches also described waiting at least 6 weeks until they received reassurance from their medical practitioner that their wounds had healed, which did not necessarily mean that they resumed sexual activity immediately after 6 weeks. It was rather another factor that women considered when planning to resume sexual activity.

Little is published regarding the partner’s views on resuming sexual intercourse after birth. Nonetheless, many women in their narratives have described him waiting for their lead on timing or coming to an agreement as a couple that sexual intercourse will be less of a priority for the first few months as they focus on adapting to their new roles. Of course, while sex may be postponed in the short-term, the conversation about sex and sexual desire needs to take place for each member of the couple to remain sexually satisfied in their intimate relationship. Complacency can set in, with sex becoming a sporadic event. On the other hand, many women feel pressure from their partners to engage in sexual intercourse after birth. In particular in couples with a limited sexual repertoire.

An example is when sexual activity and orgasm are strongly associated with penetrative sex. Some men and couples may have a ‘penetration imperative’ not having learned how to masturbate to reach orgasm. Men can solo masturbate, but mutual or intimate masturbation can also provide sexual pleasure in these circumstances. Each individual and couple must explore their own and each other’s bodies to find ways to experience sexual pleasure and climax if that is their ultimate goal.

Pregnant and post-partum women can be directed to get information on resumption of sex after birth from reputable websites. Examples might include www.babycenter.uk and www.tcd.ie/mammi/. The MAMMI study has developed a suite of videos for women and healthcare professional on sexual wellbeing after birth. They have been translated into Spanish, Dutch, Lithuanian and Romanian.

When to give information on the resumption of sexual activity after birth is fundamental and ought to be individualised to the woman, her literacy skills and preferred language. Frequently, women are discharged from maternity services 24 h after a normal birth and 72 h after a caesarean section, although this may vary from country to country. In some instances, depending on the model of maternity care, women might receive a home visit or two from a community midwife with a final post-natal assessment undertaken by a general practitioner or obstetrician approximately 6 weeks after the birth. Post-partum discharge advice often relies on a ‘tick-box’ approach, a list of wide-ranging issues that need to be discussed with a woman before discharge from maternity services. The list may include but is not limited to: post-natal depression, registering the birth of the baby, prevention of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), audiology screening, screening for metabolic disorders and contraception. This is the only window of opportunity to discuss with women when to resume sexual activity after birth in many countries. Yet, for many women, it may be an inappropriate time to bring up the topic of restarting penetrative sexual activity. It could be a time of extreme tiredness, physical discomfort, getting to know their new baby, establishing feeding and a desire to leave the maternity service and go home. This raises the question of ‘When might be the appropriate or ‘right’ time?’ to start the discussion.

One solution that could be considered is to discuss the issue of sexual health post-partum during antenatal parenthood education classes. This topic may be appropriate in antenatal discussions on adapting to parenthood after birth. However, as many women do not attend antenatal parenthood education classes, a large population of women may not receive information on sexual health after birth. Therefore, post-partum home visits, if included in the model of care or the six-week post-natal assessment, may be a more appropriate time. This final post-natal assessment has been criticised for its ‘check-list’ approach and being baby-centric, with little time devoted to maternal health and wellbeing. Frequently, contraception is belatedly addressed during this assessment, but the actual issue of resuming sexual activity is often ignored. Thus, midwives may find no alternative opportune time to address the resumption of sexual activity after birth other than as part of discharge planning. In these less-than-ideal circumstances, midwifery students and registered midwives could advise women that they can resume sexual activity when they feel physically and emotionally ready to do so while also acknowledging that this will vary from woman to woman and that it is usually planned by the woman rather than spontaneous. Women who have their birth complicated by perineal tears, sutures and/or instrumental births may be advised to avoid penetrative sex for 4–6 weeks until wounds have healed.

Women concerned about pain and discomfort during penetrative sex could also consider exploring oral sex as a means of sexual satisfaction. This may be oral stimulation of the vulva or clitoris (cunnilingus) or oral stimulation of the penis and testicles (a ‘blow job’ or fellatio). Couples might also consider solo or mutual masturbation. However, be sensitive to women’s views and norms. For example, the notion of oral sex may be offensive depending on their cultural beliefs and sexual norms. A gradual build-up to sex and artificial lubricants can also be advised. Lastly, as maternity HCPs, you should equip yourselves to comfortably, and knowledgeable provide direction for women on where to source additional evidence-based information on post-partum sexual health. This may be in web addresses, links to learning packages or support services in your area, such as sexual health midwife or nurse, psychosexual therapist or a women’s health physiotherapist or pelvic floor therapist.

5 Sexual Health After Birth: What Is Normal?

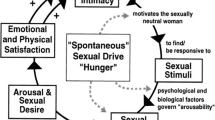

An abundance of research reports a high prevalence of sexual health issues after birth, particularly so in first-time mothers. However, wide prevalence rates vary, ranging from 18–61% 3 months after birth [9] to 9–40% at 12 months post-partum [10]. Research is generally consistent in the reported types of issues: dyspareunia (pain during penetration), vaginal lubrication, sexual desire, sexual arousal and orgasm. Many commonly used measurement tools are based on Masters and Johnson’s Sexual Response Cycle [11], suggesting that human sexual response follows a linear model progressing through four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm and resolution. This model is often criticised as being dated and male-orientated, without attention to female sexual motivation, emotional intimacy and relational dynamics. The following section examines what women, couples and healthcare professionals should consider as normative changes to sexual health after birth.

5.1 Is Dyspareunia Normal After Birth?

Genito-pelvic pain disorder is commonly referred to as sexual pain disorder or dyspareunia and often encompasses pain during sexual intercourse, pain during penetration and rarely pain at orgasm. The potential for dyspareunia during first and subsequent vaginal penetrative sexual intercourse after childbirth is possible. During the second stage of labour, the pudendal nerve can get damaged by compression from the fetal head, or stretch injury may develop from prolonged pushing. The levator ani muscles, stretched during birth, shrink post-birth. Women sometimes report a sensation of tightness that was not experienced before birth (See the pelvic floor in Fig. 8.1). Combined with frequently reported vaginal dryness post-birth, this can result in pain and discomfort during sex.

During the first 3 months post-partum, dyspareunia is common, with prevalence rates ranging from 45% to 62% [10, 12]. For many women, this is transitional. The prevalence decreases as the months pass. In a meta-synthesis of 22 studies (N = 11,457), the estimated prevalence of dyspareunia was 42% at 2 months, 43% at 2–6 months and 22% at 6–12 months [12], although remaining high enough to warrant attention. It is relevant to consider and explore the extent of dyspareunia. Is the pain mild or excruciating, constant or passing, experienced upon vaginal entry or deep penetration? Table 8.1 provides some insight into the experience of pain during the first intercourse after birth based on a study involving 1,507 first-time mothers in Australia [13]. The distressing experience of severe and persistent dyspareunia will be addressed in Chap. 14.

While it is important to inform and discuss the frequency of dyspareunia after birth with women, these prevalence rates provide limited insight into how dyspareunia impacts women and their sexual health and how they eventually resolve the pain. Consequently, the midwife’s task is to offer possible strategies and solutions for women and their partners to resolve dyspareunia and experience satisfying sexual encounters. Discuss the cycle of pain with the woman and her partner and clarify that pain results in reduced sexual arousal and lubrication. Penetration without or with minimal lubrication will cause pain. A high pelvic floor tone adds to the pain and the persisting cycle. Evidence based on women’s narratives highlights that women are active participants in seeking strategies and solutions to manage and overcome dyspareunia and that these are diverse [1]. In the first instance, midwives can support women to open the conversation with their partners about their experience of pain, encouraging women to identify where she feels the pain, what exacerbates it and what eases it. The HCP can advise women to use a slow build-up to penetration (‘slow foreplay’). Women have described engaging in self and mutual masturbation or oral sex as means of foreplay and becoming sexually aroused [1]. The midwife could suggest trying different sexual positions in which the woman has more control over penetration, such as the woman being on-top, side-lying/spooning or holding and leading the penis into the vagina. Advice should be adapted to where the woman feels pain. For instance, pain felt in the posterior vagina indicates trying the doggy position. Although women in same-sex relationships are not visible in the literature on post-partum sexual health, the principles of open communication, expressing sexual needs and trial and error concerning sexual activities that are pain-free and provide sexual satisfaction most likely are universal. Nonetheless, there is an urgent need to research this discreet population of women about their post-partum sexual wellbeing needs.

5.2 Do All Post-Partum Women Experience a Lack of Vaginal Lubrication After Birth?

Changes to vaginal lubrication are commonly self-reported by women in the immediate months after birth. For example, 57% of women experienced a lack of vaginal lubrication 3 months post-partum, reducing to 30% 12 months after birth [12]. The experience of a lack of vaginal lubrication results from fluctuating levels of circulating oestrogen post-partum. There is an immediate drop in oestrogen and progesterone after the birth of baby and placenta, with varying estimates of 6 weeks to 6 months on when levels return to their pre-pregnancy concentrations. Low oestrogen levels affect the epithelial lining of vaginal mucosa resulting in a thinning of the mucosa and a diminished lubrication capacity. Increased circulating cortisol levels can occur when new parents experience stress as they adapt to their new roles as parents, caring for a new baby. When cortisol levels rise, there is a corresponding reduction in testosterone levels. This can result in diminished sexual desire and a lack of vaginal secretions. Furthermore, decreased levels of melatonin associated with a lack of sleep are thought to hinder oestrogen secretion. For women who are breastfeeding, oestrogen levels are suppressed longer. Prolactin (necessary for lactation) is known to impact testosterone, which, coupled with tiredness and a low mood, may negatively influence sexual desire and sexual arousal.

Notwithstanding the endocrine reasons for post-partum vaginal dryness, another potential cause is not engaging in ample foreplay before penetration and thus not being sufficiently lubricated. Without proper foreplay and feelings of desire, lack of vaginal lubrication lurks. Added to that some women describe that their motivation for engaging in sexual activity was not to satisfy their own sexual desire but that of their partners. The midwife should counsel women on the frequency with which women experience a lack of vaginal lubrication post-partum and encourage women to communicate their sexual needs, desire for sexual activity or a lack of desire with their partner. A solution to manage the lack of vaginal lubrication is using a water-based lubricant during sexual activity when she really wants to engage in penetrative sex. Artificial lubricants should not be used to replace sexual stimulation and arousal completely. Midwives can recommend a good quality organic, water-based lubricant irrespective of feeding choice. Perfumed and flavoured lubricants and lubricants with superfluous additives often contain glycerine that can irritate the vagina and increase discomfort or pain. Condoms and silicon-based sex toys respond well to water-based lubricants. Silicon-based lubricants last longer than water-based lubricants (no reapplication). However, they are difficult to wash off, and they are not suitable for silicon-based sex toys or sex aids.

5.3 Do All Women Experience a Lack of Sexual Desire After Birth?

The desire for sleep and alone time can be stronger than the desire for sexual activity for many new parents during the first 12 months after birth. However, the desire for intimacy usually remains. As discussed in the introduction to this chapter, the desire for emotional and physical intimacy remains an important feature of the couple’s relationship and is a source of relationship satisfaction. Many studies report a high prevalence of a lack of interest in sex or no sexual desire ranging from 61% at 3 months post-partum to 40–51% 12 months after birth by first-time mothers [10, 13]. It is important to discuss these prevalence rates and their meanings for women and their partners. For many, the change in sexual desire experienced after birth is a normative adaptation to parenthood, particularly in the first few months. Once communicated to and understood by the couple, this often alleviates or prevents associated distress. Nonetheless, most first-time mothers were insufficiently prepared for the experience of reduced sexual desire [1]. Women who discussed their feelings on adapting to motherhood, stress associated with baby care and a lack of interest in sexual activity with their partner tended to manage the change in sexual desire with greater ease than their counterparts who had difficulty conveying their needs to their partners. When changed sexual desire is communicated honestly within the couple dyad, it becomes less problematic. Some couples give themselves time to prioritise the baby and new routines, for example, 6 months, expecting that they then can plan time-away or alone time as a couple. In the first instance, we suggest that couples prepare themselves for changes in sexual desire after birth and that they discuss the kind of pleasurable sexual activities that are not penetration-focussed. Secondly, we suggest that maternity HCPs give tips to couples on opening the dialogue on sex, that is, allocating time to discuss a sexual activity and writing down feelings and sexual desires.

In our post-partum interviews, some women described distress at their lack of sexual desire. They felt utterly unprepared for that and described their sexual relationship as ‘broken’. Many women mentioned a discordance between their own and their partner’s sexual desire. Most commonly, the male partner’s desire for sexual activity was greater than that of the female partner. The distress often materialised due to not talking to their partner about their feelings of stress in adapting to motherhood, tiredness, concern over the baby’s wellbeing, loss of sexual desire and the need to have alone time. Throughout all the literature on sexual health after birth, the consensus is that effective communication within the couple dyad on the social, relational, psychological and physical dimensions of post-partum sexual health is fundamental for post-partum sexually and emotionally satisfying intimate relationships. Maternity HCPs can suggest that couples can ‘start from the beginning’. In other words, if not used to talking about sex and sexual pleasure, they can start now. They can forget everything that has come before and outline their expectations for the next year or two regarding their intimate and sexual relationship. It is important that intimacy and affection are discussed, that each person identifies what makes them happy and feel special and that sex and sexual pleasure become part of their conversation. We suggest that couples set time aside in a neutral environment to discuss these issues. Each person should use ‘I’, owning their feelings, desires and fears and not be afraid to state what one does and does not want or enjoy. We argue that both partners take responsibility for their own pleasure. We emphasise the importance of listening to each other and asking questions.

6 Conclusions and Key Points

Post-partum sexual health is multi-dimensional. It is individual to the woman, her partner, her culture and her personal expectations. The lack of visibility of women in same-sex relationships in the literature is noteworthy and problematic. This group of women is not represented and therefore unlikely to receive post-partum sexual health information and advice relevant to their needs.

7 Key Points of Note from the Chapter

-

Post-partum sexual health is multi-dimensional, encompassing physical, social, psychological and relational dimensions.

-

Emotional intimacy and non-sexual touch are important to women and help maintain satisfying relationships. Holding hands, kissing, sleeping in the same bed, cuddling and spending alone time with her partner are valued by women and a significant part of their intimate relationships.

-

Women want specific, timely information about resuming sexual activity after birth. When can they resume sexual activity after birth? Approximately 80% of nulliparous women had resumed vaginal/penetrative sexual intercourse 3 months after birth.

-

Resuming sexual activity after birth was not spontaneous. Women and their partners planned it. Women considered their physical and emotional recovery from birth, their mode of birth and the presence of perineal trauma and abdominal wounds. They also considered being away from home and away from the baby having time to enjoy their partner’s company.

-

About 85% of nulliparous women experience discomfort during first vaginal penetration. The midwife can provide possible strategies to resolve experienced pain:

-

Slow build-up to penetration

-

Other forms of sexual activity before penetration or as a source of sexual satisfaction. For example, masturbation, oral sex, use of sex toys and sexual role play

-

Use of different sexual positions that enable the woman to control penetration, such as the woman on-top or side-lying. In the doggy position, changing the direction of the penis may provide relief depending on where she feels the pain.

-

Use of good quality, plain water-based lubricants.

-

-

One-fifth of women continue to experience dyspareunia 1 year after birth.

-

Women did resume other forms of sexual activity, e.g. masturbation and oral sex before vaginal penetration.

-

Approx. 57% of women experience a lack of vaginal lubrication in the immediate months post-partum. There are several endocrine reasons why post-partum women experience a lack of vaginal lubrication. We recommend that all women, irrespective of feeding choice, should be advised on the benefit of using a good quality water-based lubricant for first and subsequent sexual intercourse. Additive-free water-based lubricants will not irritate the vaginal wall mucosa and can be used with condoms and silicone sex toys. Artificial lubricants should not be used to replace sexual stimulation and arousal completely.

-

Maternity healthcare providers should open the conversation about post-partum sexual health antenatally and encourage women to think about and discuss their sexual preferences and needs with their partners. Couples should be advised to anticipate changes in their sexual relationship and consider strategies to manage this.

-

In couples with a ‘penetration imperative’, solo and mutual masturbation should be recommended to achieve sexual pleasure and orgasm.

-

Maternity HCPs need to be sensitive to women’s cultural and personal expectations regarding sex and intimacy since some women may be embarrassed to discuss that topic.

-

Many couples experience a change in their feelings of sexual desire as adapting to parenthood, tiredness and baby-care take priority. Discussing these feelings within the couple dyad is relevant in adapting sexual health after birth.

-

Some couples experience a discordance in feelings of sexual desire. If that is not communicated within the couple, it can cause conflict.

-

Good communication within the couple dyad is essential in maintaining good post-partum sexual health.

-

Advise women that if sexual health issues persist and cause them distress, they should speak to a healthcare professional with expertise in sexuality and intimacy.

8 Case Study

Leila, a 38-year-old first-time mother. Four months ago, she had a vacuum birth of her son Sam and acquired a second-degree tear that was sutured. Her perineum has healed well, and she has been post-natally well. She is exclusively breastfeeding Sam. Leila has a seven-year relationship with Raul, Sam’s father. They had regular, satisfying sexual encounters pre-pregnancy, at least once a week. This pattern continued during pregnancy. Since Sam’s birth, Leila and Raul tried vaginal intercourse on two occasions, 8 weeks and 12 weeks post-partum. Leila found penetration quite painful on both occasions, and she did not experience sexual satisfaction. She felt her vaginal lubrication lacking, and her vagina felt ‘tight’. Leila has told Raul of her discomfort, and he felt bad for causing her pain. Leila is aware that Raul has more feelings of sexual desire, and she feels bad because she has no desire for sex. Leila discussed these issues with her community nurse-midwife when Sam had his vaccinations.

The community nurse-midwife initially carried out an assessment. The nurse confirmed Leila’s mode of birth and if her perineum had been sutured. The nurse-midwife inspected her perineum and questioned the presence of pain or discomfort in the perineum. She asked about Leila’s recovery from birth, her feeding choice and how she and Raul were settling into parenthood. She inquired about Leila’s relationship and if they are good communicators? Do they talk about sex and sexual desire? Do they discuss adapting to parenthood and any challenges they may be experiencing? The nurse-midwife asked about their sexual relationship before pregnancy and after the birth. She asked about their preferred sexual activities and sexual satisfaction.

The nurse-midwife urged Leila to open the conversation with Raul, he was feeling bad about her discomfort during sexual intercourse, and she was feeling bad about his feelings of sexual desire. Rather than each feeling bad, it would be more beneficial to explain their feelings and make a plan.

The nurse-midwife suggested that they agree on a day and time when they can be sexually intimate, for example, a Friday or Saturday night when the baby is sleeping and when they may not have to worry about work the following day. At the weekend, they may have an opportunity to together have dinner, watch a television show or share a beer or wine. They might begin slowly engaging in some of the sexual activities they enjoyed before pregnancy and birth. The nurse-midwife suggested using a good quality water-based lubricant with no additives to assist vaginal lubrication, which may have contributed to the discomfort felt. Leila and Raul might consider mutual masturbation to lengthen foreplay and heighten Leila’s feelings of sexual desire and arousal. The nurse-midwife and Leila discussed that a sexual encounter need not end up in vaginal penetration but that each sexual encounter should provide sexual pleasure. In case they attempt penetration, the nurse-midwife suggested trying different positions, for example, Leila being on-top. This way, she can control the penetration.

Leila and the nurse-midwife talked about the statistics on the prevalence of sexual health issues after birth and how sexual desire changes for many women. Adapting to parenthood, baby care, tiredness and alone time are often higher up the priority list for women in the immediate months after birth. The nurse-midwife suggested that Raul is likely tired, is also adapting to parenthood and likely concerned about baby care, too and that his feelings of sexual desire are not known to Leila unless they discuss these feelings.

The nurse-midwife advised Leila to return to her if there was no improvement within the next 4–6 weeks to make a new plan.

References

O’Malley D, Smith V, Higgins A. Women’s solutioning and strategising in relation to their postpartum sexual health: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2019;77:53–9.

Bender SS, Sveinsdóttir E, Fridfinnsdóttir H. “You stop thinking about yourself as a woman”. An interpretive phenomenological study of the meaning of sexuality for Icelandic women during pregnancy and after birth. Midwifery. 2018;62:14–9.

Ahlborg T, Strandmark M. Factors influencing the quality of intimate relationships six months after delivery–first-time parents’ own views and coping strategies. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;27:163–72.

Hansson M, Ahlborg T. Quality of the intimate and sexual relationship in first-time parents - a longitudinal study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2012;3:21–9.

Pardell-Dominguez L, Palmieri PA, Dominguez-Cancino KA, et al. The meaning of postpartum sexual health for women living in Spain: a phenomenological inquiry. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:1–13.

McDonald EA, Brown SJ. Does method of birth make a difference to when women resume sex after childbirth? BJOG. 2013;120:823–30.

Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, Quayle J, et al. The relationship between mode of delivery and sexual health outcomes after childbirth. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1212–20.

Zhuang C, Li T, Li L. Resumption of sexual intercourse post partum and the utilisation of contraceptive methods in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026132.

McDonald E, Woolhouse H, Brown SJ. Consultation about sexual health issues in the year after childbirth: a cohort study. Birth. 2015;42:354–61.

O’Malley D, Higgins A, Begley C, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with sexual health issues in primiparous women at 6 and 12 months postpartum; a longitudinal prospective cohort study (the MAMMI study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:196.

Masters W, Johnson V. Human sexual response. New York: Little Brown; 1966.

Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, et al. Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:14–24.

McDonald EA, Gartland D, Small R, Brown SJ. Frequency, severity and persistence of postnatal dyspareunia to 18 months post partum: a cohort study. Midwifery. 2016;34:15–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

O’Malley, D., Higgins, A., Smith, V. (2023). Sexuality of the Couple in Postpartum and Early Parenthood (1st Year). In: Geuens, S., Polona Mivšek, A., Gianotten, W. (eds) Midwifery and Sexuality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-18431-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-18432-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)