Abstract

Childbirth can be experienced in many different ways. The physiological delivery is, for some women, painful and devastating. For other women, however, it can be an overwhelming sensual or nearly erotic experience that closely can resemble an orgasm. After all, delivery, orgasm and breastfeeding are similar processes, all strongly associated with oxytocin. That makes oxytocin one of the potential factors when couples look for a way to influence labour proactively. The chapter will pay attention to various aspects of physical—sexual stimuli that could affect the start of labour and its continuation. It will also describe several ways of dealing with pain and how the culture and the medical culture influence those processes. The first delivery is not only a physical process but also a significant life event, influencing the bonding between the partners towards parenthood. This chapter also looks into the partner’s role and how to navigate through this process optimally.

This chapter is part of ‘Midwifery and Sexuality’, a Springer Nature open-access textbook for midwives and related healthcare professionals.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Oxytocin

- Birthgasm

- Sexual labour induction

- Nipple stimulation (contraction) test

- Labour pain

- Pain tolerance threshold

1 Introduction

Giving birth and becoming parents encompasses many challenges, both physical, emotional and social, with changes influencing sexuality, intimacy and the relationship between the woman and her partner. This chapter will focus on the ‘sexual aspects’ of those challenges and changes.

Maybe even more than in other chapters of this book, the language used here can confuse. For some HCPs, using the word sexual in the context of delivering a baby puts them too far out of their comfort zone. Therefore terms ‘nipple stimulation’ or ‘genital touching’ appear more appropriate. For others, the ‘neutral’ use of medical or anatomical terms will create distance and debunk the intimate value of what happens.

This chapter aims to provide helpful information for optimal midwifery care during labour and birth. It will start by addressing some of the variety in ‘sexual aspects of birth’ that exists among cultures and subcultures. After that, the relation between the various elements of sexuality/intimacy and the start of labour will get attention, followed by how those elements could influence a smooth continuation of labour. We will give ample attention to the connections between sexuality/intimacy and pain relief methods used during birth.

The last part of this chapter will approach other aspects of sexuality/intimacy and relationship. The birth of a baby is a major life event for all parties involved, especially the first birth being the tipping point from woman to mother, from man to father and from couplehood to parenthood.

2 Cultural Aspects of Sexuality in Relation to Childbirth

When one mentions (during teaching HCPs) that some women undergo labour ‘nearly as a sexual experience’, part of the female students tend to react with a mixture of disapproval and denial.

On the one hand, one can consider such a reaction as a not very constructive frame of reference for good intrapartum practice. The reality is that while giving birth, some women have an orgasm (sometimes called birthgasm). For part of those women, that happens without conscious stimulation, whereas some other women deliberately stimulate themselves to orgasm to relieve labour pain. On the other hand, a reaction of ‘impossible’ apparently represents the mental scripts and communications currently dominant in their society and in ‘the medicalized culture’.

In an extensive review, Mayberry and Daniel looked at the explanations behind the apparent disconnection between sexuality and birth [1]. Among them are, for instance, deeply held negative cultural beliefs about sexuality and the gradual change from the intimacy of home birth to the more impersonal and sterile hospital settings. As a result, the current medicalised obstetric care does not favour or use the potential benefits of ‘sexual stimulation’. This reality becomes most evident in the area of pain-relief practices. Nowadays, labour and childbirth are predominantly perceived as physically painful events in various cultures. When a culture has developed the belief that that process is meant to be unbearable and traumatic, it becomes difficult for pregnant women (and HCPs) to accept the information of women who do not primarily experience the birth process as painful. Reports from anthropology made clear that in various traditional cultures, ‘sexuoerotic stimulation’ was applied by the pregnant woman, the husband or the midwife, creating a fluent birth process [2].

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Western world gradually developed a more open attitude towards sexuality and increased female autonomy. That also happened in pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, with leading roles for three professionals mentioned here. Niles Newton was an English research psychologist (1923–1993) who reintroduced the value and pleasure of breastfeeding. Sheila Kitzinger was an English anthropologist (1923–2015) and became an advocate for home birth, breastfeeding and the pregnant woman’s autonomy. Michel Odent is a French obstetrician (1930–) who became an advocate for birth without medical intervention, as long as not needed, use the doula, ‘natural oxytocin’ and (immediately after birth) skin to skin contact between mother and baby. Their approach clarified that the processes of ‘sexual’ arousal, orgasm, childbirth and lactation have much in common, all being (partially) orchestrated by oxytocin release. They made clear that each of those processes can easily be disturbed by distraction and that the woman should be able to let herself go to succeed. Those developments allowed more intimacy and acceptance of sexual/erotic aspects.

Over the last decades of the twentieth century, other developments gradually counterbalanced this process. There was an increase in the medicalisation of pregnancy and birth, with more hospital births, continuous monitoring and more medicinal interventions for pain relief (nitrous oxide, epidural anaesthesia, etc.), diminishing the women’s chances of experiencing an autonomous labouring process. These developments created the current situation in some countries, where more than half of all deliveries end in a caesarean section.

3 Sexuality and the Timely Start of Labour

In many eras and cultures, professionals and couples have been afraid that intercourse or orgasm could increase the risk of pre-term birth. In healthy pregnancies, both intercourse and recent female orgasm during late pregnancy (till 36 weeks) appeared to reduce the risk for pre-term birth [3].

This chapter deals with the consequences of sexual activity in term pregnancy.

To prevent post-term birth, unprotected intercourse is recommended as one of the strategies to initiate labour. Responsible for this effect is the exposure to prostaglandins, partly exogenous from the semen and partly endogenous from the cervical manipulation (similarly as in stripping the membranes) [4].

4 Sexual Aspects of the Induction of Labour

Internet shows numerous ‘natural ways to induce labour’ with sex mentioned frequently. Although being an important topic, very little research has been done in that area [5]. One can explain that as a taboo, but also because research in this period is complex for ethical and practical reasons. Articles on ‘sex to induce labour’ tend to limit themselves to only a part of the potential. Here we will elaborate on all the known possibilities and their accompanying explanation. The starting point of this explanation and advice is a healthy term pregnancy

4.1 Breasts and Nipples

In the early 1980s, they developed a nipple stimulation contraction test to assess fetal wellbeing, based on the finding that stimulation of the nipple(s) frequently resulted in uterine contractions in late pregnancy. In that protocol, the pregnant woman stimulated her breasts (‘through her clothes’) for 2 min, followed by 5-min rest. When there were no adequate uterine contractions, the next cycle of 2-min stimulation and 5-min rest was started, etc. One 2-min cycle or less stimulation was enough for 43% of the women, 39% needed two cycles and 15% required three cycles to induce contractions [6]. In a meta-analysis comparing breast stimulation versus no intervention, 37% versus 6% were in labour at 72 hrs [7]. In two of the breast-stimulation trials, they found an additional benefit in an 84% reduction in post-partum haemorrhage.

Of course, the mediator here is oxytocin. Around the onset of labour, uterine sensitivity to oxytocin markedly increases [8]. Implementation for the non-research practice: forget the ‘not through the clothes’, do not stop just because of a 2-min restriction, and (when feasible) let the loving partner deliver this stimulation; Stimulation will have a more intense effect when performed by the partner due to the intimate connection and (hopefully) the partner’s knowledge and experience on how to stimulate her nipples optimally.

4.2 Touch

Caressing and massage increase the level of oxytocin. Among its many effects are nurturing and sedating and anti-stress and anxiolytic effects.

4.3 Intercourse/Penetration

As long as the membranes are not ruptured, both intercourse (penetration) and ejaculation can have a function in labour induction. HCPs know that the direct internal touching/pressure of vaginal examination can cause a surge in oxytocin (the Ferguson reflex). The same happens with other forms of vaginal penetration. Such touching of the cervix also releases (endogenous) prostaglandin. Ejaculation can add a labour-inducing effect since seminal plasma contains (exogenous) prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF) in higher concentrations than in the common cervical ripening agents.

Anal penetration also causes the oxytocin release of the Ferguson reflex and the endogenous prostaglandin due to touching the cervix. The (exogenous) prostaglandins deposited in the anus will not reach the cervix but indirectly via the circulation after easy absorption through the anal wall.

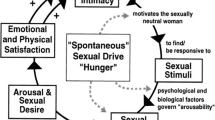

4.4 Arousal and Orgasm

Sexual arousal and orgasm both cause an increase in oxytocin levels. The increase is most clearly seen at orgasm, with, at 5 minutes after orgasm, still a high level [9]. Orgasms typically have clonic contractions, but the contraction pattern can change into one tonic contraction in the last 6-8 weeks of pregnancy. Such a strong contraction can cause rupturing of the membranes.

Some 25–30% of women experience the so-called cervico-uterine orgasm, accompanied by strong uterine contractions. That orgasm needs the stimulation of the cervical area and is orchestrated at the T12-L2 centre in the spinal cord.

Hypothesis: As long as the membranes are not ruptured, stimulating the cervix and ‘G-spot area’ with a penis, finger, dildo or vibrator could be a valuable opportunity for physiologically furthering labour.

4.5 Implementation

The limited research in this area tends to deal with only one of the above-mentioned elements. However, in daily practice, combining those various elements is expected to have an added value. The midwife appears the right professional to address those possibilities.

5 Sexual Aspects of ‘Keeping the Process Going’

After labour has started, several of the above-mentioned elements could be beneficial to keep the process going. In trying to explain the cause-effect relationship, it is difficult to distinguish between the direct influence on the progress of labour and the indirect effects by influencing the degree of experienced pain.

5.1 Touch

Well-received caressing and massage will increase the level of oxytocin, influencing both uterine contractions and relaxation. Massage also increases dopamine and serotonin levels and decreases the cortisol level [10]. With the progress of labour, an increase in plasma cortisol level is needed to maintain maternal/foetal wellbeing and facilitate the regular labour progress. Well-applied (and well-received) non-erotic or erotic skin contact may prevent cortisol levels from going too high.

5.2 Breasts and Nipples

Stimulation of breasts and nipples (especially when playful and intimate) will increase the oxytocin level and, as such, have a direct effect on uterine contractions and an indirect effect (via sedation) of less pain. The added value is bonding with the partner.

5.3 Sexual Arousal and Orgasm

An increase in oxytocin levels accompanies both sexual arousal and orgasm.

Orgasm will give strong uterine contractions and a temporary altered state of consciousness. Well-received stimulation of the genital-clitoral area has extra benefits since it significantly increases the pain threshold through endorphin release. Outside pregnancy, the effect of self-applied vaginal stimulation on pain thresholds was studied. When such stimulation produced orgasm, the pain detection threshold increased significantly by 107% and the pain tolerance threshold by 75% [11].

6 Labour Pain and Sexual Aspects

The amount of pain that people experience and remember is influenced by factors like context, cause and what the pain means to the person. For instance, chronic pain and pain related to surgery tend to be overestimated, whereas pain induced by intense sports tends to be underestimated [12]. Nearly every runner has experience with pain, and that amount is acceptable because of having control over it. There appears to be a wide variety of responses regarding recalling the pain of childbirth. Researchers compared the neurophysiology of pain at childbirth and the pain of running a marathon. Both are not only physically exhausting but also emotionally intense experiences. Oxytocin (mediating uterine contractions in childbirth and maintaining the fluid balance in running) has analgesic properties and also plays an essential role in memory formation and recall [12]. When women interpret the pain as productive and purposeful, it is associated with positive cognitions and emotions. That appears to be at least one of the context factors that create the above-mentioned variety in childbirth pain recall. A culture telling that childbirth is meant to be a painful and traumatic event neither creates positive expectations nor an atmosphere where intimacy and trust can easily develop [1].

Intimacy and trust are essential for several reasons. Trust is needed to let the process happen smoothly. Intimacy is relevant to allow the woman and her partner to feel at ease for massage, breast stimulation and other ‘pseudosexual stimulation’ by which the oxytocin and endorphin levels can increase and, in that way, keep the process going and the pain acceptable. In the choreography of ‘sexual labour pain relief’, orgasm appears the most valuable and practical element.

Besides, intimacy is a critical element of the bonding between the partners during this major life event.

7 The Relational Aspects and Sexual Implications of Childbirth

Especially the first birth is a pivotal moment in partnership. It is a major life event where the woman and her partner experience extreme fatigue and hormonal changes that strongly influence emotions. How that will affect their future relationship will depend on many different factors. There are areas on the globe where pregnancy and birth predominantly belong to the woman’s realm and where the vast majority of her social contacts are with other females. Then the male partner’s role and his reactions are relatively less critical. In other parts of the world, the connection between the woman and her partner can be rather different. Having less family around and being emotionally far more dependent on each other, their interaction during childbirth will strongly influence their bond as a couple and, subsequently, their joint parenthood. After all, the first birth is also the transition from a dyad to a triad, influencing their (sexual) relationship.

During the birth, some husbands get lost or become a nuisance. Others turn into valuable supporters by which the birth can become a moment of mutual personal growth.

A key element in that process is how the partner deals with the labour pain. Most people have no experience with the pain of someone else. When the midwife can co-create an intimate context; when the woman is open to her husband’s presence and support and when the husband can caress, massage and generate ‘intimate, physical labour pain relief’, their sexual relationship will get a boost instead of the adverse effects commonly referred to as ‘the uncoupling of birth’.

References

Mayberry L, Daniel J. ‘Birthgasm’: a literary review of orgasm as an alternative mode of pain relief in childbirth. J Holist Nurs. 2016;34:331–42.

Pranzarone GF. Sexuoerotic stimulation and orgasmic response in the induction and management of parturition – clinical possibilities. In: Kothari P, Parel R, editors. Proceedings of the first international conference on orgasm. New Delhi: Bombay VRP Publishers; 1991. p. 105–19. Available https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280495439.

Sayle AE, Savitz DA, Thorp JM Jr, et al. Sexual activity during late pregnancy and risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:283–9.

Caughey AB, Snegovskikh VV, Norwitz ER. Post-term pregnancy: how can we improve outcomes? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:715–24.

Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Sexual intercourse for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2001:CD003093.

Huddleston JF, Sutliff G, Robinson D. Contraction stress test by intermittent nipple stimulation. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63:669–73.

Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Breast stimulation for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD003392.

Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:629–83.

Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, et al. Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:27–31.

Field T, Diego MA, Hernandez-Reif M, et al. Massage therapy effects on depressed pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25:115–22.

Whipple B, Komisaruk BR. Elevation of pain threshold by vaginal stimulation in women. Pain. 1985;21:357–67.

Farley D, Piszczek Ł, Bąbel P. Why is running a marathon like giving birth? The possible role of oxytocin in the underestimation of the memory of pain induced by labour and intense exercise. Med Hypotheses. 2019;128:86–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gianotten, W.L. (2023). Sexual Aspects of Labour and Birth. In: Geuens, S., Polona Mivšek, A., Gianotten, W. (eds) Midwifery and Sexuality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-18431-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-18432-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)