Abstract

This period, especially after the first childbirth, is the litmus test of young parenthood. On the one hand, the combination of birth, perineal damage, breastfeeding, sleeplessness, and hormonal changes can strongly influence postpartum sexuality. On the other hand, the new baby has suddenly changed the dyad into a triad and is simultaneously a source of pride and pleasure and extreme fatigue and sleepless nights.

Sexual tension between the spouses regularly accompanies that process, with many men having more sexual desire and many mothers experiencing a drop in self-esteem and body positivity (next to physically being exhausted), resulting in sexual difficulties. Up to 80% of young parents experience sexual issues. In this stressful transition to parenthood, gender and gender role differences can become painfully obvious. Whereas men usually can separate fatherhood and partnership, those areas are much more intertwined in women. The grimmest consequences are increased family violence and up to 5% of the young parents who separate/divorce within 2 years after the first birth. This chapter will address the bio-psycho-social causes of those troubles and cover strategies to prevent or diminish them.

This chapter is part of ‘Midwifery and Sexuality’, a Springer Nature open-access textbook for midwives and related healthcare professionals.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Postpartum dyspareunia

- Persistent dyspareunia

- Adapting to parenthood

- Postnatal depression

- Postnatal anxiety

- Past sexual trauma

1 Introduction

The first year postpartum for new parents, whether first-time or non-first-time parents, may be complicated by many psychosocial issues, for example, challenges associated with transitioning and adapting to parenthood, the stress related to baby care, and changes to the couple’s intimate relationship (see also Chap. 8). For some women, new physical and mental health morbidities can also occur, including leaking urine, faecal incontinence, pelvic girdle pain, anxiety, depression, and sexual health problems, which can negatively impact the woman’s quality of life. In addition, pre-existing physical and mental health problems can be exacerbated during pregnancy or postpartum resulting in long-term sexual health problems, which may cause significant distress to women and couples during the first year postpartum.

2 Postpartum Sexual Health Problems

Postpartum sexual health problems can be diverse. Women experience a wide array of postpartum sexual health problems, including dyspareunia, lack of vaginal lubrication, difficulties with orgasm, and lack of sexual desire. Although these problems can self-resolve early in the postpartum period, health professionals (HCPs) must address them. Many postpartum sexual health problems can persist a year or many years after birth causing women and their partners great distress and, in some cases, relationship breakdown. The prevalence of different sexual health problems 1 year after birth varies. For example, 9% of a sample of 832 nulliparous women reported vaginal looseness, whereas 40% of these women reported a loss of interest in sex [1]. Studies indeed indicate that women experience sexual health problems during the first year after birth. These may be new-onset, associated with underlying medical or mental health illness or exacerbated by birth and the postpartum period [2, 3]. Before we discuss these issues, it is important to realize that many studies apply the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to measure the prevalence of sexual problems. Therefore, we will first pay some attention to the challenges and limitations of the studies that use the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to measure prevalence.

3 The Complexities of Diagnoses of Postpartum Sexual Health Problems

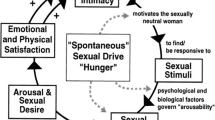

Estimating the prevalence of postpartum sexual health problems is complex and challenging. Numerous papers and reports label postpartum women as sexually dysfunctional or having sexual health problems. They base that on the results of studies that utilize the FSFI scale. The FSFI measures sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, achieving orgasm, dyspareunia, and sexual satisfaction [4], with lower scale scores (<26) used as markers of sexual dysfunction. Using the FSFI, however, is problematic for several reasons. The scale originated from the dated and disputed Master and Johnson’s Sexual Response Cycle [5], that is now obsolete. Their response cycle described a linear model progressing through four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution, and it was fundamentally identical in men and women. Thus, it took no account of women’s motivation for sex, sexual desire, relational dynamics, or emotional intimacy needs, all considered important to women’s sexual response [6].

Since the FSFI scale was neither developed for postpartum sexual health nor validated with postpartum women, using the FSFI for this discrete population is questionable and problematic. Classifying women as being sexually dysfunctional on the FSFI results alone ignores the complexity of postpartum sexual well-being and the potential influence of the broader context of women’s lives and relationships, including the impact that adapting to parenting roles, extreme tiredness, and concern over baby’s well-being may have on sexual function and intimate relationships.

The subsections below examine some of the commonly experienced new-onset sexual health problems encountered in the first year after birth. We also look at common pre-existing conditions affecting sexual well-being after birth.

3.1 Persistent Dyspareunia

Many primiparous women experience dyspareunia in the initial months postpartum.Footnote 1 In many cases, it will resolve itself, or the couple can manage it with some simple strategies. However, there is evidence that some women may experience distressing and long-term dyspareunia that can negatively impact their quality of life and relationships with their partners. An Australian cohort study demonstrated that 28% (333/1184) of primiparous women continued to experience dyspareunia 12 months postpartum and 23% (261/1155) at 18 months. One in ten of the women with dyspareunia described the pain as ‘distressing’, ‘horrible’, or ‘excruciating’ [7]. While it is difficult to identify risk factors for intense dyspareunia, McDonald and colleagues report that caesarean section birth was associated with intense pain 6 months after birth when they considered other maternal and obstetric factors [7]. However, the study did not report whether the caesarean section was an elective or emergency procedure. We believe that relevant since an emergency caesarean section and possible protracted labour might influence the association with the intense pain reported in McDonald’s study. There is evidence that severe perineal trauma increases the likelihood of experiencing ‘difficulty with coitus’. This difficulty was explained as a lack of sexual desire, pain at the vaginal orifice during penetration, and/or pain during deep penetration [8]. While it may be challenging to identify women who are at risk of developing intense dyspareunia, it is important that maternity HCPs provide woman and couple-centred support and advice for these women and their partners.

In the first instance, women need to be supported and encouraged to talk to their partner about their experience of pain, how it makes them feel, and how it affects their desire for sexual activity. We may advise the couple to try different sexual positions, lubricants, and alternative sexual activities. When these strategies have been unsuccessful, we recommend advising the couple to make an appointment with their general practitioner (GP) or gynaecologist. We suggest that the couple attends as the problem is a couple’s issue, not solely a postpartum woman’s issue.

The detailed assessment by the HCP should include information on pre-pregnancy sexual activity and sexual intercourse, mode of birth, traumatic birth, perineal trauma, infant feeding method, use of contraceptives, time of resumption after birth, and type of resumed sexual activities. The woman’s age, the possibility of perimenopausal symptoms, and the side effects of prescribed medication contributing to the experience of pain need to be considered. The HCP should ask about the experience of pain, including whether it is a new-onset pain post-birth, where and when precisely the pain is felt, for example, on penile entry, during deep penetration or both, and whether the pain is superficial and isolated to the vulva or vaginal entrance or felt in a particular area of the vagina only. The woman should describe any sensation associated with the pain, for example, feelings of spasm, burning, tightness, or friction. Vaginal and urinary tract infections will need to be ruled out as causative factors of pain. Especially in intense dyspareunia, psychosocial issues, such as relationship problems, mental health issues, drug and alcohol misuse and current or past physical, emotional or sexual trauma, need to be addressed. The HCP has to perform such a thorough assessment sensitively, aware of the potential for embarrassment and couple distress. Likely, the woman’s partner may also be experiencing distress at the notion that he may be causing his partner to experience intense pain during vaginal penetration. Thus, a good strategy is asking for permission to talk about this sensitive topic, starting with the least sensitive questions and progressively moving to more sensitive areas of inquiry, meanwhile explaining the rationale for each question (see Chap. 26 on ‘talking sexuality’). Recognizing the need for help and making an appointment to see their HCP are significant steps for many couples. Still, the HCP needs to remain cognisant of the sensitive nature of the conversation by using language that the couple understands, explaining professional terms, and avoiding euphemisms, such as ‘down below’ when referring to the vagina or penis.

Depending on the findings from the assessment and the available services, the HCP may advise the couple to attend a women’s health physiotherapist or pelvic floor therapist. They can teach strategies to ease sensations of tightness and spasms, such as how to stretch pelvic floor muscles. Some couples need a referral to a clinical sexologist or sex therapist may be warranted for couples who require support to discuss and resolve possible underlying relationship issues, traumatic birth experiences, or past trauma. See details in Chap. 29. A psychosexual therapist may educate the couple on how sex therapy works, relaxation therapy and hypnotherapy as tools to help in instances of sexual pain problems or vaginismus. Psychosexual therapy may include developing a programme with the couple involving progressive touching, kissing, and exploring each other’s bodies but avoiding vaginal penetration.

Some women/couples need a referral to a gynaecologist to investigate the physical source of the pain. For example, persisting pain after the repair of a severe perineal tear may need close examination under general anaesthetic (GA) and maybe minor surgery to repair scar tissue. Some women have found relief from using a local anaesthetic during penetration, such as lignocaine, when pain is localized and accessible. We should adapt any referral or strategy to the couple’s needs and be assured they agree.

4 Adapting to Parenthood

In much of the discussion on sexual well-being after birth, we identify that the relationship between the couple is paramount: a relationship of trust, which facilitates vulnerability and is characterized by good communication. However, the stress associated with adapting to parenthood can cause conflict in a relationship. Adapting to parenthood has been described as a serious drain on couples’ emotional, physical, and material resources [9], which ultimately can result in relationship breakdown. In their 8-year follow-up study of new parents, Hansson and Ahlborg [10] determined that a couple’s sensual and sexual satisfaction levels decreased in the first 4 years after birth and had not returned to early postpartum levels 8 years after the birth of the first child. It is likely that couples need support and help to adapt to parenthood while maintaining a satisfying intimate and sexual relationship. This help might take the form of preparing for potential changes to sexual well-being commonly experienced, as outlined in Chap. 8. Strategies to support maintaining sexual well-being in the long term might include planning time alone as a couple away from family and home, scheduling time for intimate touch and sex if they wish, expanding their sexual repertoire beyond penetrative sex, opening a dialogue on sex, communicating other needs, such as support with childcare, household chores, or financial strains. Psychosexual therapy and couple therapy might also be an option for some couples.

5 Pre-Existing and Perinatal Mental Health Issues

Some women who become pregnant and give birth have underlying or pre-existing mental health conditions. While it is not within the scope of this chapter to review how all these conditions impact postpartum sexual well-being, it would be remiss not to address some of the more common mental health conditions in maternity care, namely, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Chapters 17 and 18 address, in detail, several pre-existing medical and mental health conditions and how they may impact sexual well-being.

5.1 Postnatal Depression

Postnatal depression (PND) is estimated to affect 10–15% of women in the months after birth. Symptoms may vary from poor appetite (or comfort eating), guilt or negative thoughts, inability to enjoy things, difficulty looking after the baby and self, to feeling that life is not worth living. Depression (in general) and PND are associated with sexual health problems. In PND, the symptoms of mood disorders such as low self-esteem, feelings of helplessness, and fatigue negatively impact women’s sexual well-being. Furthermore, many antidepressants can cause or exacerbate existing sexual health problems.Footnote 2 Between 50–70% of people with depression and antidepressants experience iatrogenic sexual dysfunction such as low sex drive, arousal, and orgasm [11]. The most commonly reported adverse sexual effects in women taking antidepressants are problems with sexual desire (72%), sexual arousal (83%), and orgasm (42%) [12]. Yet, the relevant HCPs neither tell women how depression can impact their sexual well-being, nor that prescribed antidepressant medication can impair their sexual function.

Chapter 8 mentioned that women in same-sex couples are absent from the discussions on postpartum sexual well-being. This is also the case in the literature on mood disorders and women in same-sex relationships, even though depression appears more prevalent in same-sex couples than in opposite-sex couples [13].

A multidisciplinary team approach to caring for a woman experiencing PND is important. Care and treatment plans should take a holistic view of the woman, her family life, her working life, her support systems, and her relationship with her partner. Strategies to manage the sexual problems associated with PND may include behavioural approaches (exercising before sexual activity, scheduling sexual activity, vibratory stimulation, psychotherapy), complementary and integrative therapies (acupuncture, nutraceuticals), or a combination of these modalities. If sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant medication is an issue, strategies may involve dose reduction, drug discontinuation or switching, augmentation, or using medicines with lower adverse effect profiles. Sexual well-being is an essential aspect of a couple’s intimate relationship. Sexual well-being between couples enables a unique closeness and vulnerability within the couple-dyad that is not shared by anyone else.

For some women with depression, sex is the only domain of their life that is less or not affected by their depression. That reality can be helpful as a wellbeing-anchor or even a tool for looking at depression.

5.2 Postnatal Anxiety

The literature on postnatal anxiety appears less conclusive, with discrete prevalence rates difficult to source because anxiety frequently merges with PND in discussions on mental health after birth. Nonetheless, a systematic review and meta-analysis (102 studies, N = 221,974 women) demonstrated that 15% of women had self-reported anxiety symptoms 6 months after childbirth, and 9% had a clinical diagnosis of any anxiety disorder [14]. Postnatal anxiety symptoms include constant or near-constant feelings of nervousness or panic, persistent worries about self, baby or relationship, and being prone to panic attacks. Self-confidence, self-esteem, perception of body image, feelings of sexual desire, and arousal may all be negatively impacted. The experience of postnatal anxiety and sexual problems can become a cyclical response. Feelings of anxiety may lead to worsening vaginismus and dyspareunia due to muscle tension. This can aggravate feelings of stress, isolation, and worry about self and relationship. Managing anxiety is a priority, but we should as well address the woman’s concerns and symptoms. Among the possible tools to manage anxiety are medication, psychotherapy, and mindfulness. The last two are valuable strategies to deal with anxiety-related sexual health problems. Additionally, communication within the couple, planning alone time as a couple, exploring what activities give pleasure without the pressure of sexual activities experienced as threatening. Issues around body image and self-esteem may need exploration by a psychotherapist.

When the couple feels ready, they can try to redevelop via prolonged foreplay, sex toys, lubricants, masturbation, oral sex, et cetera, and a gradual build-up towards penetrative sex.

5.3 Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Birth Trauma

A traumatic birth experience or birth trauma can have a lasting impact on a woman and her entire family. Birth trauma might result from an obstetric emergency, an instrumental birth, emergency caesarean section, or long, painful labour. Equally, factors not associated with ‘clinical’ issues per se can also be causal, including feeling ignored or not being listened to by caregivers during birth or feeling powerless and a sense of loss of control. The impact of birth trauma can result in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Estimates of clinically diagnosed PTSD following childbirth range from 5.6% to 9%. However, the rate of women with post-traumatic stress symptoms but not meeting the complete PTSD diagnosis is 18% [15]. Women with PTSD are sometimes misdiagnosed as depressed or anxious, although these can present as co-morbidities. Symptoms of birth trauma can be severe and vary from feelings of anxiety, panic, and fear to nightmares and flashbacks, triggered by smells, images, and sounds, resulting in reliving the traumatic experience. Some women describe difficulty coping and bonding with their baby, and some experience feelings of guilt, shame, and worthlessness. Notwithstanding the personal distress women with birth trauma experience, there is also evidence that explores the impact of birth trauma on a couple’s relationship. Women have described their relationship with their partners as being ‘shattered’ [16]. A Norwegian cohort study (N = 1,480) showed poor relationship satisfaction in women with postpartum PTSD at 2 years after birth [17]. In postpartum PTSD, sexual relationships are frequently affected, with loss of intimacy and reduced sexual activity. Women reported having flashbacks when initiating sex or avoiding sexual intercourse due to fear of becoming pregnant and going through childbirth again [18]. Much of the advice and support offered to women, in this case, is similar to what we have described earlier: communicating fear and worries with their partner, planning intimacy, extended foreplay, and agreeing where touch is welcome on the body, birth debriefing, psychotherapy, and survivor support groups.

5.4 Past Sexual Trauma

Global estimates vary, but approximately one in five women experience some form of sexual trauma/violence from 16 years. Sexual trauma or sexual abuse is sexual contact or behaviour that occurs without the explicit consent of the victim. It may range from attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching, forcing a victim to perform sexual acts, such as oral sex or penetrating the perpetrator’s body or penetration of the victim’s body, also known as rape in many countries.

Estimates of the incidence of rape are difficult to obtain. The proportion of women who reported rape lies between 8% and 12% in Western countries. International trends demonstrate an annual increase in reported cases. With most sexual abuse in women occurring before age 24, many of these women will have pregnancies and birth experiences that will be influenced by that sexual trauma. Postpartum care practices, such as examining the perineum and breasts, exposing their body to the gaze of others, and triggering language, for example ‘lie still’, are issues that women who have experienced sexual trauma have identified as being challenging for them and potential triggers to flashbacks of trauma. For some women, breastfeeding may be rife with triggers. For others, it can become a healing process. Since many of these issues can potentially re-traumatize the woman, we must provide sensitive, individualized, trauma-informed care. More on this issue can be found in Chap. 24.

It is important to consider women who got pregnant due to rape and how we should support these women in adjusting to motherhood and baby care. The juxtaposition of emotions is complex and unique to each woman. Depending on the legislation in their country, an abortion may not be an option. Then, the woman may feel further trapped and traumatized by continuing the pregnancy and birthing the baby. They may choose not to care and hand the baby in for adoption. Women may disclose or not disclose reasons for putting their baby up for adoption. HCPs should, either way, provide non-judgemental care supporting women in the choices they make.

On the other hand, some women may decide to continue with the pregnancy, believing that something positive and life-affirming can come from the trauma. Though the woman actively decided to continue the pregnancy, the childbirth may re-traumatize and impose a visual reminder of the past sexual abuse. A baby boy may be significant to the woman, with physical features that remind the woman of the perpetrator. We recommend HCPs ask about infant feeding choices and about support with baby care. We should explain to the mother that attachment between mother and child can be a complex and rewarding process for all women, irrespective of how conception occured. The woman may wish to speak to whoever has supported her in her recovery from the sexual abuse, family, friend, therapist, or support group facilitator. We must respect her wishes, document them, and communicate them to all care-team members.

5.4.1 Interventions to Support Women and Partners

It sometimes takes months or even years to recover from PTSD, birth trauma, and sexual trauma. Women might need the support of specialist professionals, which would likely include birth debriefing, psychotherapy, and survivor support groups. Women may experience PTSD, depression, and anxiety due to the trauma. Maternity care providers must recognize their limitations in supporting these women and know the referral pathways available in their maternity services. Maternity care providers must ensure that women are not lost in these pathways by following up on any referrals made via phone calls or confirmatory emails and incorporating trauma-informed care in each woman’s pregnancy and birth journey.

6 Addressing Diversity

Women in same-sex relationships, single women, young women, women with multiple partners, and women from smaller cultural communities (e.g. Roma community) are absent from the literature and discussions on postpartum sexual well-being. While some of the discussion in Chap. 8 on everyday postpartum sexual well-being might well apply to these groups of women, we cannot state this with confidence about problematic postpartum situations. The nuances of these women’s intimate relationships and their relationship priorities during the first year postpartum may differ from the standard population participating in research on sexual health after birth. Study samples tend to be heterosexual, in long-term relationships, over 30 years, and well educated to a degree level or above. To ensure inclusive and truly woman-centred care, there is an urgent need to develop strategies that include these women groups in research.

Key Points of Note from the Chapter

-

Many women experience sexual health problems in the months and years after birth.

-

There is difficulty in interpreting prevalence rates of postpartum sexual health problems due to the overreliance on FSFI, a partially obsolete measurement tool.

-

One-fifth of women continue to self-report dyspareunia 12–18 months after birth, with 10% of them describing their pain as ‘distressing’, ‘horrible’, or ‘excruciating’.

-

Identifying risk factors for persistent dyspareunia is difficult, but severe perineal trauma may be a risk factor.

-

If different sexual positions, lubricants, and alternative sexual activities do not resolve persistent dyspareunia, the couple deserves referral to a sexuality-positive GP for a detailed assessment and management plan.

-

Additional referral may be needed to a psychosexual therapist, women’s health physiotherapist, or a gynaecologist.

-

Some parents struggle to adapt to parenthood. If left unattended, this has the potential to cause a broken relationship.

-

Postnatal depression and the medications used to treat postnatal depression can complicate postnatal sexual health problems.

-

Postnatal anxiety and the complexity of symptoms experienced by women can lead to a cyclical response whereby sexual pain problems worsen, and women’s anxiety increases.

-

Women with PTSD and birth trauma may experience co-morbidities of depression and anxiety. The trauma experience can harm the couple’s relationship and sexual relationship.

-

One in five women globally experiences some form of sexual violence.

-

In a woman with past trauma, aspects of postpartum care, body exposure, and inappropriate language can re-traumatize her.

-

When the pregnancy resulted from rape, the woman deserves extra attention regarding attachment to the baby.

-

Maternity care providers must recognize their limitations in supporting women with PTSD, birth trauma, and past sexual abuse. They need to be familiar with their local services and available referral pathways.

-

Women in same-sex relationships, single women, young women, women with multiple partners, and women from smaller cultural communities are all absent from the literature and discussions on postpartum sexual health problems.

References

O'Malley D, Higgins A, Begley C, Daly D, Smith V. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with sexual health issues in primiparous women at 6 and 12 months postpartum; a longitudinal prospective cohort study (the MAMMI study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:196.

Lipschuetz M, Cohen SM, Liebergall-Wischnitzer M. Degree of bother from pelvic floor dysfunction in women one year after first delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;191:90–4.

Galbally M, Watson SJ, Permezel M, Lewis AJ. Depression across pregnancy and the postpartum, antidepressant use and the association with female sexual function. Psychol Med. 2019;49:1490–9.

Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208.

Masters W, Johnson V. Human sexual response. New York: Little Brown; 1966.

Basson R. Are our definitions of women’s desire, arousal and sexual pain disorders too broad and our definition of orgasmic disorder too narrow? J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:289–300.

McDonald EA, Gartland D, Small R, Brown SJ. Frequency, severity and persistence of postnatal dyspareunia to 18 months post partum: a cohort study. Midwifery. 2016;34:15–20.

Fodstad K, Staff AC, Laine K. Sexual activity and dyspareunia the first year postpartum in relation to degree of perineal trauma. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:1513–23.

Pacey S. Couples and the first baby: responding to new parents’ sexual and relationship problems. Sex Relationship Ther. 2004;19:223–46.

Hansson M, Ahlborg T. Quality of the intimate and sexual relationship in first-time parents—a longitudinal study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2012;3:21–9.

Rothmore J. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Med J Aust. 2020;212:329–34.

Lorenz T, Rullo J, Faubion S. Antidepressant-induced female sexual dysfunction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1280–6.

Pakula B, Shoveller JA. Sexual orientation and self-reported mood disorder diagnosis among Canadian adults. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:209.

Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:315–23.

Beck CT, Gable RK, Sakala C, Declercq ER. Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: results from a two-stage U.S. national survey. Birth. 2011;38:216–27.

Fenech G, Thomson G. Tormented by ghosts from their past’: a meta-synthesis to explore the psychosocial implications of a traumatic birth on maternal well-being. Midwifery. 2014;30:185–93.

Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A, Handtke E, et al. The impact of postpartum posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms on Couples’ relationship satisfaction: a population-based prospective study. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1728.

Delicate A. The trauma between us. AIMS. 2019;30(4).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

O’Malley, D., Smith, V., Higgins, A. (2023). Sexual Aspects of Problems in the Postpartum and Early Parenthood (1st Year). In: Geuens, S., Polona Mivšek, A., Gianotten, W. (eds) Midwifery and Sexuality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-18431-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-18432-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)