Abstract

In line with the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) Statement on the Cooperative Identity and definition of a cooperative enterprise (ICA in Guidance notes to the co-operative principles. https://www.ica.coop/en/media/library/research-and-reviews/guidance-notes-cooperative-principles, 2015), we set out to frame a theory of cooperative governance with the focus on a collective membership, whereby control of the enterprise is acquired by engaging with (via patronage/usership/work) rather than investing in the firm. The term often used to describe this type of enterprise is “member-owned business” (MOB; Birchall in People-centred businesses: Co-operatives, mutuals and the idea of membership. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), underscoring the primacy of member contribution to the operations and governance of the enterprise in different capacities as workers, consumers, and suppliers, rather than merely investors.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The dominant theories of corporate governance equate effective governance practices to meeting the enterprise owners’ goals, typically to increase company value and maximize return on investment. This understanding draws on the premise that ownership of capital grants residual control, and residual income rights over the enterprise (Hansmann, 1996).Footnote 1 With the formal separation of ownership and control in modern corporations (Berle & Means, 1932; Fama & Jensen, 1983), various theories of governance, most notably the principal-agent theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), as well as new institutional economics and transaction costs theories, rest on particular assumptions about human behaviour that give rise to extrinsic incentive structures, which purport to resolve agency issues in organizations (Grundei, 2008; Klein et al., 2012). Stewardship theory (Davis et al., 1997; Muth & Donaldson, 1998), on the other hand, draws on different behavioural assumptions, in which the manager is intrinsically motivated, identifies with organizational goals and does not behave opportunistically as a result (Grundei, 2008).Footnote 2

These two conflicting theories lead to diverging conclusions about governance structures, particularly the role and makeup of the board of directors (Cornforth, 2004). The board has a hierarchical monitoring and control function under the agency model, yet a collaborative supporting and advisory role under the stewardship model; board directors represent the owners in the former case, while they provide stakeholder expertise in the latter.

While many researchers suggest that each theory has value in different contexts (see Sundaramurthy & Lewis, 2003; Cornforth, 2004; or Cullen et al., 2006), cooperative governance continues to be discussed from the asset ownership perspective of maximizing the value of the firm (investor logic) rather than from the perspective of the membership relation with the enterprise (“usership” logic, Borgen, 2004).Footnote 3 Cooperatives and other democratically governed enterprises in the social solidarity economy (SSE) have a different raison d’être. Their governance therefore ought to align with their purpose and organizational logic.

In line with the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) Statement on the Cooperative Identity and definition of a cooperative enterprise (ICA, 2015), we set out to frame a theory of cooperative governance with the focus on a collective membership,Footnote 4 whereby control of the enterprise is acquired by engaging with (via patronage/usership/work) rather than investing in the firm. The term often used to describe this type of enterprise is “member-owned business” (MOB; Birchall, 2010), underscoring the primacy of member contribution to the operations and governance of the enterprise in different capacities as workers, consumers, suppliers, rather than merely investors.

The associational character of the enterprise is a hallmark of cooperatives, as expressed through collective ownership, contributions, and benefit (Novkovic et al., 2022), with implications for governance of collective assets and income distribution decisions. The right to control the enterprise is a right of membership (i.e. a personal right),Footnote 5 rather than a property right (Borgen, 2004; Ellerman, 2021; Lutz & Lux, 1988), while ownership of cooperative assets is collective (at least in part), rather than individual. For these reasons, as well as the inherent feature of cooperative organizing to foster human dignity, we place greater emphasis on the usership logic of coop membership in thinking through governance challenges and incentive problems (see Novkovic & Miner, 2019).

While legal ownership is a necessary condition under most institutional settings, it is not a sufficient condition for control of the cooperative enterprise, where voice in primary cooperatives is granted on a one-person-one-vote basis. We, therefore, approach cooperative governance from the humanistic theory perspective (Lutz, 1999; Lutz & Lux, 1988; Pirson & Turnbull, 2011; Schumacher, 1973; Tomer, 2002) and a member-use-own-control relationship with the enterprise. This, to us, goes beyond the agency or stewardship relationship between the board of directors and hired managers, although humanism subscribes more closely to the behavioural assumptions of a steward, coupled with cognitive limitations that require systems for collective accountability. The humanistic theoretical foundations centre economic activity around human needs and human development, instead of capital accumulation. In contrast to neoclassical “homoeconomicus”, it recognizes the dual—or, more accurately, complex—nature of human beings in simultaneously satisfying both self-interest and mutual interest; addressing basic needs alongside social and economic justice (Lutz & Lux, 1988). More broadly, humanism in economics presupposes the existence of absolute social values independent of individual preferences and market demand; the goal of economic activity is to satisfy basic human needs and promote dignity for all and to involve meaningful work as a primary vehicle for human development (Lutz & Lux, 1988, pp. 146–149).

CooperativesFootnote 6 then, as mutual self-help organizations, represent a microeconomic institutional form built on the premise of satisfaction of both personal needs and collective needs and aspirations (see the ICA Statement, 1995); their governance is emergent and diverse, depending on context (Morgan, 1986), as elaborated in Novković et al., Chapter 4 in this volume. Governance systems evolve over time in cooperative organizations, as new challenges and opportunities arise, or new members with changing needs and aspirations join the organization.

Table 2.1 summarizes the key differences in assumptions and ensuing governance characteristics between the investor-centred and humanistic, people-centred form of enterprise, framing the rest of the chapter.

2 Behavioural Foundations

The fundamental question of human nature and its complex social expression as human behaviour in an organizational setting gives rise to diverse theories of governance. Contrary to the one-dimensional utility maximiser of neoclassical economics, and principal-agent theory building on that premise (Jensen & Meckling, 1994), humanistic management scholars argue that there exists a growing “consilience of knowledge” spanning the natural sciences, the humanities, and the social sciences, which indicates that humans are driven by a mixture of independent lower-order (economistic) and higher-order (humanistic) impulses and needs (Lawrence & Nohria, 2002, as cited in Pirson, 2017). This complexity perspective on human nature is anticipated by the humanistic economics conception of a “dual self” (Lutz & Lux, 1988; Lux & Lutz, 1999), which maps onto the “human firm” (Tomer, 2002) and, in particular, underpins the dual (or complex)—economic and social; individual and collective; associational and business—nature of cooperatives (Novkovic, 2012; Novkovic et al., 2022; Puusa et al., 2016).

While psychologists assign “dual motives” and a need to balance physiological brain function (Cory, 2006; see also Tomer, 2012), humanistic economists attach the important proviso that the balance existing within this duality is socially and institutionally mediated (Lux & Lutz, 1999; Novkovic, 2012; Puusa et al., 2016). In contrast to the optimizing behaviour of so-called rational economic man (Tomer, 1992), Simon proposes that actual human decision-making is characterized by bounded rationality (1979, p. 501). The existence of organizations (vs sole reliance on independent market exchanges—see Williamson, 1973) can be perceived as a necessary outcome of human inability to fully process information under conditions of complexity and uncertainty (Ghoshal & Moran, 1996; Simon, 1979). Hence organizational decision makers satisfice rather than optimize/maximize in their search for the best alternative course of action—that is, they utilize “rules of thumb” to arrive at decisions that are good enough for now (Simon, 1979). Systematic decision-making bias in the collection, processing, and deployment of information also occurs due to normative and affective involvements, signalling the contradictory and complex reality of human motivation (Tomer, 1992). Therefore, the design of governance structures ought usually to incorporate an element of accountability, taking into consideration human limitations in information processing, rather than necessarily opportunism assumed by agency theory. This approach places mutual support instead of mistrust at the centre of governance design.

These alternative, heterodox microeconomic foundations, derived from humanistic strands of behavioural economics (Tomer, 2007, p. 477; see also Lutz, 1999; Tomer, 2002, 2017) and organizational psychology (Lovrich, 1989), more accurately describe the behaviour of organizational decision makers in their search for a satisfactory balance between—and possible synergy of—collaboration and control mechanisms under conditions of uncertainty and change. An overemphasis on either agency-inspired or stewardship-inspired management practices may set in motion reinforcing degenerative cycles of control or collaboration, respectively (Ghoshal & Moran, 1996; Sundaramurthy & Lewis, 2003). In the former case, excessive use of controls creates and reinforces distrust; while in the latter case, the potential for groupthink arises.

For our purpose, bounded and affective/normative rationality and a particular point of view reflected in the type of relationship a member may have with the cooperative (worker, producer, consumer or other; insider or outsider) will affect behaviour and provide further context for evolving governance dynamics and structures. This is evident in the development of diverse democratic processes and practices to ensure accountability and distribution of power among a larger group of members. Human limitations, but also the need for transparency, necessitate a separation of governance powers through a variety of independent “control centres” (multiple boards reflecting multiple stakeholder perspectives through network governance), which operate as a system of checks and balances on organizational decision-making (Pirson & Turnbull, 2011).

The logic of network governance draws on the behavioural insight that “human beings have limited ability to receive, store, process, retrieve, and transmit information” (ibid., p. 103, original emphasis). In light of human processing limitations, the division of decision-making tasks among many specialists and coordination of their work through some form of communication, authority, and accountability structure was also proposed by Herbert Simon (1979, p. 501). MultistakeholderFootnote 9 network governance has the potential to reduce individual and group biases and avoid information overload facing unitary board structures (Pirson & Turnbull, 2011). This feature is then likely to emerge in people-centred democratic organizations such as cooperatives.Footnote 10

3 The Purpose of the Enterprise

Theories of corporate governance assume that the firm’s purpose is to maximize its financial value (return on investment). A relatively strict separation of ownership and control, coupled with opportunistic self-serving behaviour of management gives rise to agency problems. In a cooperative firm, the members are the owners, and in many cases—particularly in worker cooperatives—also the managers, who are elected to governance structures by and accountable to the wider membership. Hence, the assumptions of agency theory lose relevance in a context where some or all owners and controllers are also co-op members. In the ideal scenario (a worker-inclusive multistakeholder co-op—see Girard, 2015; Lund, 2011; Novkovic, 2019), “All ‘agents’ are also ‘principals’, so there is little or no separation of ownership and control” (Turnbull, 2000, p. 51). At least in theory, then, interest alignment should be high (Eckart, 2009, p. 70).Footnote 11

Assumptions of the stewardship model (and partly the stakeholder model) of governance (see Cornforth, 2004) have, therefore, greater resonance in a cooperative organizational setting, where there is generally less of a conflict between firm ownership and control (Eckart, 2009); although the implied expert board structure under the stewardship model may be in conflict with the democratic nature of cooperative enterprise. Democratic, bottom-up organizations such as cooperatives have an embedded control mechanism when members can voice their potential disapproval directly to the management of the cooperative (Eckart, 2009), or through democratic representation on various governance and oversight bodies. This can potentially allow for a degree of managerial oversight unthinkable within conventional firms and is perhaps all the more effective as compared to the traditional top-down control mechanism; especially if such bottom-up control were to take a more collaborative form. Proximity of members to the organization is critical in effectively fulfilling this role. Depending on the reasons for cooperative formation by its members, member-owners may also work in the organization, or supply its inputs, provide services, or consume its products. Separation between management and governance functions may be blurred at times, but this is often necessary (see Wilson, 2021), and a source of reduced transactions costs.

The interest, or purpose, of members and the cooperative organization depends on many factors—there is no one size fits all cooperative enterprise. However, use-value as reflected in the provision of dignified work, or high-quality products, access to markets, fair pricing, or a social mission, binds cooperatives together through shared values and identity,Footnote 12 epitomized in economic democracy.Footnote 13 The stakeholder value maximization hypothesis of modern property rights theory (MPRT; see Klein et al., 2012), while broadening the beneficiaries of enterprise success beyond shareholders, is different from the cooperative membership and use-value proposition. While the former is about distribution of residual income, the latter is about mutual self-empowerment. Stakeholders have a transactional relationship with the enterprise according to MPRT, with capital ownership still granting control rights, although recognizing that other stakeholders also contribute to value creation. Members in a cooperative, on the other hand, are collective owners and users of the enterprise, engaging with it in multiple ways (Mamouni Limnios et al., 2018), including as members of the community. Ultimately, stakeholder representation in governance does provide a different point of view; however, financial return remains central in the stakeholder model, while “activity instead of profitability” (Vienney, as cited in Malo & Bouchard, 2002) guides the motivation of cooperative members.

A host of a priori critiques have been mounted against the cooperative organizational form, employing the investor logic of the principal-agent and property rights theories (Borgen, 2004; Fama & Jensen, 1983). The critiques generally revolve around purported investment- and decision-related incentive problems in cooperatives (free-riding; portfolio problem; investment horizon, etc.; see Cook, 1995; Dow, 2003). The salient point here is not that such investment—and decision-related incentive problems can’t or don’t arise in cooperative organizations, but that they arise only in certain circumstances, rather than as inherent properties of the cooperative organizational form. Instead of adopting stringent a priori assumptions, Borgen (2004) outlines the factors impacting those incentive problems, such as heterogeneous membership and misalignment of individual and organizational goals, the amount of member financial contributions, and the degree of members’ involvement with the cooperative. However, the extent to which these conditions arise and constitute a significant problem depends largely on “whether members are essentially ascribed the reasoning and strategic interests of a rational investor or a rational user” (ibid.). Borgen argues that the former behavioural logic characterizes the investor-owned firm, while the latter is more characteristic of a cooperative ownership structure; even if the two roles may be blended in reality. Therefore, governance issues in cooperatives may arise due to misalignment of the investor logic and the member-centred characteristics of cooperative enterprise (ibid.).

4 The Nature of Ownership, Control, and Distribution

As described above, democratic member-owned enterprises such as cooperatives are collectively owned by their members, who gain rights to control the enterprise and engage in its operations—as suppliers, workers, or consumers. Members’ responsibility includes securing finance, typically through membership shares and retained earnings, but also by issuing debt or equity financial instruments that do not grant control rights. Cooperatives create reserves and accumulate wealth that is transferred to the next generation of members (Hesse & Čihák, 2007).

Intergenerational organizational stewardship is embedded in the cooperative structure (Bancel & Boned, 2014; Borgen, 2004; Lund & Hancock, 2020; Tortia, 2018).Footnote 14 Indeed, a cooperative ideology and value system, based on intergenerational stewardship, underpins the longstanding success and vibrancy of the impressive network of cooperatives in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna (Lund & Hancock, 2020), and the Mondragon cooperative network in the autonomous Basque region of Spain, among others (Pirson, 2017; Sanchez Bajo & Roelants, 2011). Indivisible reserves serve as a mechanism to reduce risk, ensure cooperative resilience and longevity, and secure cooperative survival as a member-owned organization (Tortia, 2018). Indivisible reserves are also a mechanism that enables job security and income smoothing in worker cooperatives (Navarra, 2016).

The collective, intergenerational ownership feature of cooperatives is supported by humanistic approaches in economics and management, while it contradicts the mainstream enterprise and governance studies. Positioning the purpose of cooperative enterprise as serving the needs of a “rational user” (Borgen, 2004) sets the stage for the development of structures that ensure enterprise longevity, to secure its use-value with impact on the broader community (Erdal, 2014; Gordon-Nembhard, 2014).

Increasingly, cooperatives are also described as “commons” due to their collective governance and intergenerational reciprocity as a self-organized institutional attribute (Azzellini, 2018; de Peuter & Dyer-Witheford, 2010; Perilleux & Nyssens, 2017; Tortia, 2018). Mutualizing costs and benefits, pooling and sharing, is the modus operandi of cooperation, shared with the commons (Bollier & Helfrich, 2019, p. 178), since cooperation involves interpersonal relations, rather than pure transactions such as in market exchanges. The operating mechanisms among the members are relations of trust, reciprocity, and mutuality as opposed to equivalent exchange (see Zamagni, 2008). Zamagni in particular points to the proportionality of this relationship where every member contributes fairly in proportion to their ability.

Besides collective ownership, the residual income distribution in cooperatives as not-for-profit organizations is also a feature poorly understood in the governance literature and policy circles (Levi & Davis, 2008). The patronage dividend in cooperatives and the investment dividend based on capital share ownership are often confused, as illustrated by the exclusion of cooperatives from the definition of Non-Profit Institutions in the UN System of National Accounts (2008), based on the non-distribution constraint requirement in the definition.Footnote 15 The patronage dividend or patronage income (Lutz & Lux, 1988, p. 174) is a mechanism for price adjustment, rather than a return on investment. Prices (in the case of suppliers or consumer members) or wages (for worker members) are set as advance payments under uncertainty. At the end of the accounting period patronage dividends are distributed based on the level of contribution, i.e. “use” of the enterprise (sales, purchases, or hours worked, respectively). The distribution of income, including into indivisible reserves, is democratically determined by the members.

The nature of firm ownership and control in the case of cooperatives, therefore, is fundamentally collective. The logics and incentive structures generally applied to “rational” capitalist investors are hence severely curtailed, if not outright redundant, where co-op membership/usership is concerned. This is evident in the empirical experiences of successful cooperative enterprises and movements that have adhered to the coop identity in a suitably flexible and evolving manner.

5 Governance Systems

The concern with cooperative governance in the literature is usually about the principle of democracy and challenges it poses for the governance structure, namely providing a satisfactory balance on a unitary board of directors between representation and voice of members, while also ensuring elected directors’ expertise (Birchall, 2017; Cornforth, 2004). We expand this focus to suggest that democratic governance is often inclusive of different stakeholders, and conjecture that democratic organizations practice network governance (Turnbull, 2002) and polycentricity (Allen, 2014; Ostrom, 1990, 2010) as a natural fit for the multiple-stakeholder concerns of people-centred organizations. While all cooperatives share democratic/participatory governance, democratic processes, and organizational structures are contingent on a number of internal and external factors, as elaborated in separate chapters in this volume. Importantly, members’ and stakeholders’ continuous involvement and engagement with the organization provides the normative framework for “best practice” in cooperative governance, but it needs to be amplified by the organization’s embeddedness in society and the natural environment, i.e. external factors (Aguilera et al., 2015).

Governance structures, processes, and their dynamic exchanges, forming the system of governance (Eckart, 2009), are shaped in cooperatives as a democratic and participatory interaction among members. In the foundation stage, these interactions are direct and deliberative, but they evolve as cooperatives grow and move into different stages in their lifecycle. What participation means, and how democracy plays out may shift over time, but how it changes also depends on the context—the type of members, regulatory frameworks, changing perceptions and needs, and shifting economic, social, and environmental conditions.

The extent to which participatory democratic governance is actualized and sustained in cooperatives will be a question both of internally driven processes of member and organizational “reproduction”Footnote 16 (Gand & Béjean, 2013; Stryjan, 1994) and externally driven processes of institutional and competitive isomorphism (Bager, 1994). These internal and external processes, in turn, interact with prevailing governance structures to create dynamic organizational change over time—that is, governance structures and processes coevolve in a contingent manner (Bager, 1994; Eckart, 2009; Stryjan, 1994). Stryjan (1994) and Cornforth (1995) recentre attention on the fundamental importance of cooperative reproductive processes, noting an overemphasis in cooperative studies on degeneration, and organizational structure. Key to the co-op reproduction process from this perspective is the part played by member (and worker) recruitment, onboarding, development, and turnover. Meaningful democratic participation also involves encouraging open communication between co-op members at a manageable scale (Basterretxea et al., 2022; Cannell, 2010; Stacey & Mowles, 2016).

What then are the external mechanisms bearing upon this internal process of member and co-op reproduction? Most macroeconomic institutions today are hostile to member-owned democratic enterprises, where investment is not the source of organizational control. The same can be said of globally accepted regulatory frameworks, such as recommended accounting practices, financial products and regulation, rating systems, and so on. This external environment has to be carefully navigated and cooperatives steered in line with their values and identity. This opens up an opportunity for institutional collaborative processes that generate organizational homogeneity between cooperatives (Bager, 1994; Gand & Béjean, 2013; Sacchetti & Tortia, 2016; Stryjan, 1994).

While “isomorphism” is used in organizational literature to indicate unintended changes (DiMaggio & Powell 1983), Bager (1994) proposes two different forms of isomorphism relevant for the transformation of cooperatives: congruent and non-congruent isomorphism. Most authors focus on non-congruent organizational isomorphism and its causes, particularly in cooperatives emulating structures and processes of investor-owned enterprises, and competing in a capitalist market economy. Congruent institutional and competitive isomorphic processes, on the other hand, can be strengthened through mutualistic network and federation building among cooperatives (Arando et al., 2010; Novkovic, 2014; Roelants et al., 2012; Sacchetti & Tortia, 2016; Smith, 2001, Zanotti et al., 2011); and through the cooperative movement building alliances with other political and social movements that share similar values and a self-help ethos, such as the labour movement, social solidarity economy, the commons, and the environmental movement (Azzellini, 2018; Bager, 1994; Bollier & Helfrich, 2019; de Peuter & Dyer-Witheford, 2010; Miller, 2010; Utting, 2016; Vieta, 2020). Key performance indicators, measures, and reporting also play an important role in delivering on the vision and strategy (see Côté, 2019; also see Novković & Simlesa, Chapter 14 in this volume). Cooperative governance, then, is about steering the organization in the right direction for the long haul; it will be situation and context-specific, driven by members, their needs, and the needs of the next generation of members.

6 Concluding Remarks

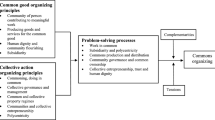

Cooperative identity translates into a unique enterprise model with specific characteristics: it is people-centred, jointly owned and controlled by its members; and democratically governed (Novkovic & Miner, 2015). Member participation with rights and responsibilities as “users” (workers, producers, consumers etc.), contributors to democratic governance, and to capitalization of the enterprise is an integral part of the enterprise model, while values and principles of cooperation inform the processes of member and stakeholder engagement, and purpose of the enterprise. Cooperative governance and business strategy ought to reflect the cooperative identity.

The chapter sets the stage for cooperative governance built on humanistic economics and management theories, as opposed to the reductionist assumptions in neoclassical and new institutional economics that dominate the corporate governance literature. A more holistic view of human beings with complexities, multiple goals and motives, and including human needs and ethics in the decision-making process, provides the background for a different understanding of the purpose of the enterprise, and the nature of user-ownership and control. These together form the bases for democratic governance and management systems within values-based cooperative enterprises.

Most prominent theories of governance give rise to rigid systems, with a particular focus on the role of the Board. Humanistic foundations, on the other hand, suggest that the systems of democratic cooperative governance will be diverse, and context dependent, while promoting human dignity and satisfying human needs. Structures that follow humanistic theories may include multiple centres of decision-making (polycentricity and network governance); member and stakeholder participation; distribution of power; distributional equity, and possibly a blurred line between management and governance, depending on context. Humanistic democratic and participatory processes may include representative and direct forms, conflict resolution practices, formal and informal communications. The dynamic interplay between cooperative governance structures and processes under internal and external pressures can be navigated to sustain humanistic organization only through regular and adaptive governance system review and renewal (Cornforth, 2004; Grundei, 2008). Best co-op governance also requires extending outwards through mutualistic organization within the cooperative movement, and by coordinating with like-minded allies (Bager, 1994; Sacchetti & Tortia, 2016).

Notes

- 1.

While classical property rights theory defines ownership as rights to residual income (left after all contractual obligations are met), modern property rights theory suggests ownership grants the residual control rights (Klein et al., 2012). Hansmann (1996) considers both these rights as rights of ownership, inflicting transactions costs upon enterprise owners.

- 2.

While this literature focusses on board–management relationships and dynamics, similar logics apply to other stakeholders like workers or community supporters.

- 3.

When democratic cooperative governance is considered in the literature, it is usually focussed on the political decision making and the role and makeup of the (typically) unitary Board (Birchall, 2017; Cornforth, 2004; Spear, 2004). The focus of this book is on cooperative solutions to governance challenges stemming from their democratic nature, rooted in humanistic theory; emergent and diverse due to different contexts, not least of which the type and nature of membership.

- 4.

Note that the membership, or “usership”, perspective here refers to different types of members engaged in diverse operations with the co-op, including as workers, consumers, producers, community supporting members, or a mix. While members in a cooperative also provide a part or all of its working capital, financing a co-op is a means to a different purpose. Mutual enterprises, for example, require zero investment from their member policy holders, yet they maintain the control rights over the enterprise.

- 5.

Lutz and Lux liken it to the political voting right in a particular area, granted when one lives there, but not transferable and revoked when one moves (1988, p. 173).

- 6.

Cooperatives are understood here as a benchmark model for democratically governed, values-based, and member-owned and controlled enterprises, rather than the only organizational form satisfying these conditions.

- 7.

Vienney, as cited in Malo and Bouchard (2002).

- 8.

Cooperative stakeholders are motivated by solidarity and a shared objective they can realize through a cooperative enterprise. They each bring a different perspective to the table, but their interests align to work toward cooperative viability and adherence to cooperative values (Novkovic & Miner, 2015, p. 12).

- 9.

- 10.

This requires fundamental attention to the promotion of cooperative organizational culture, associative/collective intelligence (Laloux, 2014; MacPherson, 2002), and trust building in social-communicative relations within and between the various nodes of nested decision making (Stacey & Mowles, 2016).

- 11.

Confronting theory with practice, however: while stewardship potentialities are more apparent in small, and in inclusive and participatory worker and multistakeholder cooperatives, in other types of cooperative, joint ownership is usually limited to outsider membership types and control is often delegated to Boards, or in some cases, to externally hired managers.

- 12.

- 13.

We subscribe to the broad definition of economic democracy, to imply the transfer of decision-making authority from shareholders to key stakeholders (members: workers, consumers, producers, and/or relevant community members).

- 14.

This type of stewardship is reflected in the protection of collective assets, such as collectively-owned equity and indivisible reserves, i.e. creating a fixed portion of co-op equity that cannot be paid out in member dividends. See Principle 3, Guidance notes on the cooperative principles (ICA, 2015).

- 15.

Article 23.21. states that a co-operative can be included in the Non Profit Institution accounts only “if the articles of association of a co-operative prevent it from distributing its profit, then it will be treated as an NPI; if it can distribute its profit to its members, it is not an NPI (in either the SNA or the satellite account)” (SNA, 2008, p. 457).

- 16.

Reproduction is about the cycle of membership selection, engagement, and renewal. This process is impacted by the organisational lifecycle and is closely intertwined with external isomorphic pressures.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Desender, K., Bednar, M. K., & Lee, J. H. (2015). Connecting the dots: Bringing external corporate governance into the corporate governance puzzle. The Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 483–573.

Allen, B. (2014). A role for co-operatives in governance of common-pool resources and common property systems. In S. Novkovic & T. Webb (Eds.), Co-operatives in a post-growth era: Creating co-operative economics (pp. 242–263). Zed Books.

Arando, S., Gago, M., Jones, D. C., & Kato, T. (2010, January 3–5). Productive efficiency in the Mondragón Cooperatives: Evidence from an econometric case study. Paper presented at Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA) Annual Conference, Atlanta. https://www.slideshare.net/slides_eoi/saioay-monica-productividad-en-la-cooperativas-de-mondragon

Azzellini, D. (2018). Labour as a commons: The example of worker-recuperated companies. Critical Sociology, 44(4–5), 763–776.

Bager, T. (1994). Isomorphic processes and the transformation of cooperatives. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 65(1), 35–59.

Bancel, J.-L., & Boned, O. (2014). Heirs and annuitants of co-operative banks—Three principles for securing the long-term future of co-operative governance. International Journal of Cooperative Management, 7(1), 90–93.

Basterretxea, I., Cornforth, C., & Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2022). Corporate governance as a key aspect in the failure of worker cooperatives. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 43(1), 362–387.

Berle, A., & Means, G. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. Commerce Clearing House.

Birchall, J. (2010). People-centred businesses: Co-operatives, mutuals and the idea of membership. Palgrave Macmillan.

Birchall, J. (2017). The governance of large co-operative businesses. Co-operatives UK. https://www.ica.coop/en/media/library/research-and-reviews/governance-large-co-operative-businesses

Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (2019). Free, fair, and alive: The insurgent power of the commons. New Society Publishers.

Borgen, S. O. (2004). Rethinking incentive problems in cooperative organizations. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 33(4), 383–393.

Cannell, B. (2010). Break free from our systems prison: Implications of complex responsive process management thinking. Paper presented at the UKSCS Conference, Wales. https://www.academia.edu/36658111/Break_Free_from_Our_Systems_Prison

Cook, M. L. (1995). The future of US agricultural cooperatives: A neo-institutional approach. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 77(5), 1153–1159.

Cornforth, C. (1995). Patterns of cooperative management: Beyond the degeneration thesis. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 16, 487–523.

Cornforth, C. (2004). The governance of cooperatives and mutual associations: A paradox perspective. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 75(1), 11–32.

Cory, G. A. (2006). The dual motives theory. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics (Formerly the Journal of Socio-Economics), 35(4), 589–591.

Côté, D. (2019). Cooperative management: An effective model adapted to future challenges. Les Éditions JFD Inc.

Cullen, M., Kirwan, C., & Brennan, N. (2006). Comparative analysis of corporate governance theory: The agency-stewardship continuum. Paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference of the Irish Accounting & Finance Association, Institute of Technology, Tralee. https://www.academia.edu/2173809/Comparative_analysis_of_corporate_governance_theory_the_agency_stewardship_continuum

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47.

de Peuter, G., & Dyer-Witheford, N. (2010). Commons and cooperatives. Affinities: A Journal of Radical Theory, Culture, and Action. https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/affinities/article/view/6147

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Dow, G. K. (2003). Governing the firm: Workers’ control in theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Eckart, M. (2009). Cooperative governance: A third way towards competitive advantage. Südwestdeutscher Verlag für Hochschulschriften.

Ellerman, D. (2021). The democratic worker-owned firm: A new model for the East and West. Routledge.

Erdal, D. (2014). Employee ownership and health: An initial study. In S. Novkovic & T. Webb (Eds.), Co-operatives in a post-growth era: Creating co-operative economics (pp. 210–220). Zed Books.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325.

Gand, S., & Béjean, M. (2013, June). Organizing sustainable democratic firms: Processes of regeneration as the design of new models of cooperation. 13th Annual Conference of the European Academy of Management, EURAM 2013, Istanbul, Turkey, 30 pp. https://hal-mines-paristech.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00881721

Ghoshal, S., & Moran, P. (1996). Bad for practice: A critique of the transaction cost theory. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 13–47.

Girard, J. (2015). Governance in solidarity. In S. Novkovic & K. Miner (Eds.), Co-operative governance fit to build resilience in the face of complexity (pp. 127–133). International Co-operative Alliance. https://www.ica.coop/en/media/library/cooperative-governance-fit-build-resilience-face-complexity

Gordon-Nembhard, J. (2014). Benefits and impacts of cooperatives. White paper, Howard University Centre on Race and Wealth, and John Jay College CUNY. https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/0213-benefits-and-impacts-of-cooperatives.pdf

Grundei, J. (2008). Are managers agents or stewards of their principals? Journal Für Betriebswirtschaft, 58(3), 141–166.

Hansmann, H. (1996). The ownership of enterprise. The Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press.

Hesse, H., & Čihák, M. (2007). Cooperative banks and financial stability (IMF Working Paper WP/07/02). https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2007/wp0702.pdf

International Cooperative Alliance (ICA). (1995). Statement on the Cooperative Identity. https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity

International Co-operative Alliance (ICA). (2015). Guidance notes to the co-operative principles. https://www.ica.coop/en/media/library/research-and-reviews/guidance-notes-cooperative-principles

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1994). The nature of man. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 7(2), 4–19.

Klein, P. G., Mahoney, J. T., McGahan, A. M., & Pitelis, C. N. (2012). Who is in charge? A property rights perspective on stakeholder governance. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 304–315.

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations: A guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage of human consciousness. Nelson Parker.

Levi, Y., & Davis, P. (2008). Cooperatives as the “enfants terribles” of economics: Some implications for the social economy. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(6), 2178–2188.

Lovrich, N. P. (1989). The Simon/Argyris debate: Bounded rationality versus self-actualization conceptions of human nature. Public Administration Quarterly, 12(4), 452–483.

Lund, M. (2011). Solidarity as a business model: A multi-stakeholder cooperatives manual. Cooperative Development Center, Kent State University. https://community-wealth.org/content/solidarity-business-model-multi-stakeholder-cooperatives-manual

Lund, M., & Hancock, M. (2020). Stewards of enterprise: Lessons in economic democracy from northern Italy (ICCM Working Paper & Case Study Series 01/2020). https://www.smu.ca/webfiles/WorkingPaper2020-01.pdf

Lutz, M. A. (1999). Economics for the common good: Two centuries of economic thought in the humanist tradition. Routledge.

Lutz, M. A., & Lux, K. (1988). Humanistic economics: The new challenge. Bootstrap Pr.

Lux, K., & Lutz, M. A. (1999). Dual self. In P. E. Earl & S. Kemp (Eds.), The Elgar companion to consumer research and economic psychology (pp. 164–169). Edward Elgar.

MacPherson, I. (2002). Encouraging associative intelligence: Co-operatives, shared learning and responsible citizenship (Plenary presentation). Journal of Co-operative Studies, 35(2), 86–98.

Malo, M.-C. & Bouchard, M. (2002). En hommage à Claude Vienney (1929–2001). Revue internationale de l’économie sociale, 283, 5–14.

Mamouni Limnios, E., Mazzarol, T., Soutar, G. N., & Siddique, K. H. (2018). The member wears Four Hats: A member identification framework for co-operative enterprises. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 6(1), 20–33.

Miller, E. (2010). Solidarity economy: Key concepts and issues. In E. Kawano, T. N. Masterson, & J. Teller-Elsberg (Eds.), Solidarity economy I: Building alternatives for people and planet (pp. 25–41). Centre for Popular Economics. https://www.academia.edu/2472194/Building_a_Solidarity_Economy_from_Real_World_Practices?from=cover_page

Morgan, G. (1986). Images of organization. Sage.

Muth, M., & Donaldson, L. (1998). Stewardship theory and board structure: A contingency approach. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 6(1), 5–28.

Navarra, C. (2016). Employment stabilization inside firms: An empirical investigation of worker cooperatives. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 87(4), 563–585.

Novkovic, S. (2012). The balancing act: Reconciling the economic and social goals of co-operatives. In E. Molina & M. Robicheaud (Eds.), The amazing power of co-operatives (pp. 289–300). International Summit of Co-operatives.

Novkovic, S. (2014). Co-operative networks and organizational innovation. In C. Gijselinckx, L. Zhao, & S. Novkovic (Eds.), Co-operative innovations in China and the West (pp. 47–63). Palgrave Macmillan.

Novkovic, S. (2019). Multi-stakeholder cooperatives as a means for jobs creation and social transformation. In B. Roelants, H. Eum, S. Esim, S. Novkovic, & W. Katajamaki (Eds.), Cooperatives and the world of work (pp. 220–233). Routledge.

Novkovic, S., & Miner, K. (Eds.). (2015). Co-operative governance fit to build resilience in the face of complexity. International Co-operative Alliance. https://www.ica.coop/en/media/library/cooperative-governance-fit-build-resilience-face-complexity

Novkovic, S., & Miner, K. (2019). Compensation in co-operatives: Values based philosophies (ICCM Working Paper and Case Study Series 01/2019). https://smu.ca/webfiles/ICCMWorkingPaper19-01.pdf

Novkovic, S., Puusa, A., & Miner, K. (2022). Co-operative identity and the dual nature: From paradox to complementarities. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 10(1), 100162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcom.2021.100162

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2010). Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American Economic Review, 100(3), 641–672.

Perilleux, A., & Nyssens, M. (2017). Understanding cooperative finance as a new common. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 88(2), 155–177.

Pirson, M. (2017). Humanistic management: Protecting dignity and promoting well-being. Cambridge University Press.

Pirson, M., & Turnbull, S. (2011). Toward a more humanistic governance model: Network governance structures. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(1), 101–114.

Puusa, A., Hokkila, K., & Varis, A. (2016). Individuality vs. communality: A new dual role of co-operatives? Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 4(1), 22–30.

Roelants, B., Dovgan, D., Eum, H., & Terrasi, E. (2012, June). The resilience of the cooperative model. How worker cooperatives, social cooperatives and other worker-owned enterprises respond to the crisis and its consequences. CECOP-CICOPA Europe. https://ess-europe.eu/sites/default/files/report_cecop_2012_en_web.pdf

Sacchetti, S., & Tortia, E. (2016). The extended governance of cooperative firms: Inter-firm coordination and consistency of values. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 87(1), 93–116.

Sanchez Bajo, C. B., & Roelants, B. (2011). Capital and the debt trap. Palgrave Macmillan.

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: Economics as if people mattered. Blond & Briggs.

Simon, H. A. (1979). Rational decision making in business organizations. The American Economic Review, 69(4), 493–513.

Smith, S.C. (2001). Blooming together or wilting alone? Network externalities and Mondragón and La Lega co-operative networks (WIDER Discussion Papers, 2001/27). World Institute for Development Economics (UNU-WIDER). https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/blooming-together-or-wilting-alone

Spear, R. (2004). Governance in democratic member-based organisations. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 75(1), 33–59.

Spear, R. (2011). Formes cooperatives hybrides. Recma: Revue internationale de l’ťeconomie sociale, 320. http://oro.open.ac.uk/32268/2/Cooperative_HybridsRECMA_Spear.pdf

Stacey, R., & Mowles, C. (2016). Strategic management and organisational dynamics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Stryjan, Y. (1994). Understanding cooperatives: The reproduction perspective. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 65(1), 59–79.

Sundaramurthy, C., & Lewis, M. (2003). Control and collaboration: Paradoxes of governance. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 397–415.

System of National Accounts (2008). United Nations; European Commission; International Monetary Fund; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; World Bank. UN Publication. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/sna2008.asp

Tomer, J. F. (1992). Rational organizational decision making in the human firm: A socio-economic model. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 21(2), 85–107.

Tomer, J. F. (2002). The human firm: A socio-economic analysis of its behaviour and potential in a new economic age. Routledge.

Tomer, J. F. (2007). What is behavioral economics? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 36(3), 463–479.

Tomer, J. F. (2012). Brain physiology, egoistic and empathic motivation, and brain plasticity: Toward a more human economics. World Economic Review, 1, 76–90.

Tomer, J. F. (2017). Advanced introduction to behavioral economics. Edward Elgar.

Tortia, E. C. (2018). The firm as a common. Non-divided ownership, patrimonial stability and longevity of cooperative enterprises. Sustainability, 10, 1023.

Turnbull, S. (1995). Case study: Innovations in corporate governance: The Mondragón experience. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 3(3), 167–180.

Turnbull, S. (2000). Corporate governance: Theories, challenges and paradigms. Gouvernance: Revue Internationale, 1(1), 11–43.

Turnbull, S. (2002). A new way to govern: Organisations and society after Enron. New Economics Foundation. https://neweconomics.org/2002/08/new-way-govern

Utting, P. (2016). Mainstreaming social and solidarity economy: Opportunities and risks for policy change (UNT-FSSE Background Paper, 12). https://base.socioeco.org/docs/paper-mainstreaming-sse-12-november-2016-edit-untfsse.pdf

Vieta, M. (2020). Workers’ self-management in Argentina: Contesting neo-liberalism by occupying companies, creating cooperatives, and recuperating autogestión. Brill and Haymarket Books.

Williamson, O. (1973). Markets and hierarchies: Some elementary considerations. The American Economic Review, 63(2), 316–325.

Wilson, A. (2021, June 17–19). Challenging governance orthodoxies [Keynote address]. 2021 International Cooperative Governance Symposium. Halifax, NS. https://www.smu.ca/webfiles/CHALLENGINGGOVERNANCEORTHODOXIES(Wilson).pdf

Zamagni, S. (2008). Reciprocity, civil economy, common good. In M. S. Archer & P. Donati (Eds.), Pursuing the common good: How solidarity and subsidiarity can work together (pp. 467–502). Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

Zanotti, A. (2011). Italy: The strength of an inter-sectoral network. In A. Zevi, A. Zanotti, F. Soulage, & A. Zelaia (Eds.), Beyond the crisis: Cooperatives, work, finance generating wealth for the long term (pp. 21–100). CECOP Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Novković, S., McMahon, C. (2023). Humanism and the Cooperative Enterprise: Theoretical Foundations. In: Novković, S., Miner, K., McMahon, C. (eds) Humanistic Governance in Democratic Organizations. Humanism in Business Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17403-2_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17403-2_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-17402-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-17403-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)