Abstract

Climate change is significantly impacting local communities throughout Indonesia that are dependent on access to ecosystems and weather-dependent resources. This chapter explores how local resource governance systems shape responsiveness and adaptive capacity of communities to pressures and change. Drawing on two comparative cases studies of coastal communities in Indonesia, this chapter conveys how active responses to environmental pressures and change over resource and land conflict, are indicative of adaptive capacity and how communities are likely to adapt to climate change impacts. The chapter argues through illustrative examples that local resource governance determines innovation and engagement through collective handling, reciprocity, cooperation and coordinated action, in order to adjust and adapt in dealing with environmental pressures, elite capture, conflict and change.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

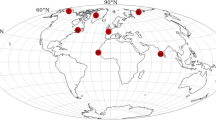

Understanding the ways local communities can govern, innovate, and engage adaptation strategies to deal with environmental stresses and change, including climate, is crucial knowledge for Indonesia, as the impacts of climate change in Indonesia, combined with other disaster types, continue to rise (Djalante, 2018; EMDAT, 2020). This chapter, therefore, presents a case study perspective on local ways of governing, innovating, and engaging adaptation strategies at local community levels. Based on a comparative study of two cases in Java and Maluku of rural coastal areas, the chapter documents ongoing local resource governance processes adopted by local communities in adapting to land-use pressures and environmental change. The first case study takes place in the conjoined villages of Haruku and Sameth on Haruku Island, in Central Maluku. Here, both customary land and marine management are practiced (known in the region as Sasi) for marine, agroforestry and agricultural livelihoods. The second case study takes place in the Karangsewu and Bugel villages of Kulon Progo, Yogyakarta, in JavaFootnote 1 where residents have transformed the coastal sand plains from marginal non-productive arid land, to productive agriculture with some of the highest yielding chili crops in Indonesia.

The sites selected for this study were chosen based on indicative earlier studies and preliminary discussions within the communities selected. These noted the roles that collective resource governance and innovation have played in both communities, in strategies actively tackling other (nonclimate) types of social and environmental pressures and change, thereby also propelling responses to climate change. The selected sites rate as highly vulnerable to climate impacts but rank as having high social resilience among studies (Batiran & Salim, 2020; Gaspersz & Saiya, 2019; Hallatu et al., 2020; Mony et al., 2017; Supriyanto et al., 2012). Both case sites report that their active resilience came through local agency, self-determination, and collective action, driving adaptive capacity to respond to change. Each case has overcome resource governance pressures and conflicts over land or marine areas and resources, with resource extraction pressures being typical between both. A comparative case study approach was adopted specifically in order to understand the diverse social actors and practices at play in these settings, and their responses to broader political, social, cultural, economic, and environmental drivers (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2016) as well as how motivations and levels of influence work together (Bourdieu, 1977; Giddens, 1984).

Individual and group semistructured interviews were undertaken during 2019 and 2020, in each of the two sites. In the first site, these interviews were conducted in Indonesian language with Ambon and Haruku dialects (from Maluku), and in the second site, interviews were conducted mixed in Javanese and Indonesian languages. The interviews were transcribed and translated to English,Footnote 2 and then coded using a grounded theory approach to develop themes from the data collected. The grounded theory allows for the coding of cases for conceptual development in generating theories of process, sequence and change in social interactions, organization, and roles (Glaser & Strauss, 1987). Grounded theory was therefore selected for the research methodology given that it compliments case study usage, allowing work through a continuous inductive interplay between data collection and analysis to discover themes (Martin & Turner, 1986; Myers, 2009).

2 Climate Change as Part of a Complex Array of Social-Environmental Pressures

Throughout the world, impacts and extreme events stemming from climate change significantly affect climate-dependent activities such as those based on agriculture, fishing, and natural-resource-dependent livelihoods (Dodman et al., 2014). At the same time, climate change disproportionately affects rural and natural resource-dependent populations and the rural poor (Dasgupta et al., 2014). Many rural and natural resource-dependent communities face long-term factors such as land degradation and conversion, along with issues around access, governance and conflict that predate or are unrelated to climate change (Ireland & McKinnon, 2013). Climate change serves to exacerbate these existing context-specific factors and inequalities at the local level (Ayers, 2010), with climate change compounding other factors pertinent to rural areas, such as a lack of access (compared with urban areas) to services, infrastructure, investment, inputs into decision-making and information (Dodman et al., 2014).

For rural and natural resource-based populations in Java and Maluku, alongside rapid economic and population growth, Indonesia’s disparity between rich and poor has grown faster than in any other country in Southeast Asia (Gibson et al., 2017) having the sixth-worst socioeconomic discrepancy of any nation globally (Gibson et al., 2017). Around 9.5% of the total population in Indonesia were living below the poverty line in 2019,Footnote 3 which translates into around 26.42 million people out of Indonesia’s 270.2 million population (World Bank, 2020). A majority of this figure is the 15 million (or 53.45%) of Indonesia’s poor living on the island of Java (BPS, 2016). While conversely, in the islands of Maluku with a significantly smaller population than Java, 22% of the area’s population lives below the poverty line, making Maluku the region with the highest percentage of poverty per capita (BPS, 2016). The livelihood sources of the majority of people in both areas are small-scale farming, fishing, and trade work (BPS, 2020). Markedly, in each region, rural farmers and indigenous groups also disproportionately represent Indonesia’s poor (BPS, 2020). Leveraging on these context-specific factors, and exacerbating inequalities at the local level, climate change has had significant impacts in both case studies in Java and Maluku.

In both case studies, climate change has reportedly resulted in coastal inundation, increased storms and winds, floods and flash floods, increased heat and periods of heat (increasing labor requirements for watering and changes to watering timings), rain variability, as well as increased and new pest incidence, and accompanying crop and yield loss. Climate change has also affected the traditional usage of agricultural and fishing calendars and the ecosystem signaling that communities have relied upon for generations to manage land and natural resources, as well as the livelihoods dependent on these. In Maluku, for example, climate change has significantly affected the ocean currents, influencing fish patterns and the timing of fish cycles. Impacts from climate change have compounded in both cases with the ongoing conflicts and environmental pressures faced by the local communities in each. Residents in both case studies have continuously responded by adapting to climate change among other pressures and change types through collective local resource governance mechanisms over years.

Combining with the rising impacts of climate change, issues over land governance continually emerge to keep local communities that are dependent on natural resources and land access subject to ongoing environmental pressure and change. Rural (and indigenous) communities in Indonesia dependent on natural resources and land access, hold access to these under varied, yet tentative rights. Accordingly, vulnerabilities exist alongside increasingly complex cross-scale relationships between communities and globalized forces culminating amidst other challenges and with socio-economic disparity playing out in the ways that populations have control over, or access to, natural resources and land use. How this translates into land access and governance is problematic as fierce competition over land as a commodity expands. Land conflict, for example, is a prominent feature across Indonesia. Conflict continues to arise alongside ongoing pressures on resources and access to land, with the demand for both surging. The number of active land conflicts throughout Indonesia has continued steadily to increase, most frequently occurring in rural areas where livelihoods depend on managing land resources (Handoko et al., 2019).Footnote 4

Rural (and indigenous) communities in Indonesia that are dependent on natural resources and land access often hold access under tentative rights because in practice, legal use is often difficult for rural and indigenous populations to assert. The pressure for individual land titles and competing interests continues between the acquisition of land under corporate entities and increasing commercialization of land (McCarthy & Robinson, 2016) and alongside state land (re)acquisitions. Land conflicts being widespread throughout Indonesia are also due in part to discrepancies between legal use and actual use, and the ability of the rural poor and indigenous people to access rights and legal justice. Immense divergences between formal land-use allocation and ownership within the state registration system and the actual land-use situation in practice (McCarthy, 2017) determine access to land and natural resources and with economic disparity playing out in the ways that populations have control over, or access to, natural resources and land use. These complexities force communities at local levels in rural areas toward collective action on knowledge, policy, and practice (Warren & McCarthy, 2009). Hence, rural communities’ resilience also mediates rural areas’ vulnerability to climate change, such as indigenous knowledge and networks of mutual support (Dodman et al., 2014).

3 Climate Change Adaptive Capacity and Governance Responses to Pressure and Change

Adaptive capacity is defined by the IPCC as “the ability of systems, institutions, humans, and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences” (IPCC, 2022). Adaptive capacity is often explicitly emphasized by the two sides to adaptation in either proactive or reactive responses to impacts (Adger et al., 2007; Ford et al., 2013; Gallopín, 2006; Hill & Engle, 2013; Hinkel, 2011; Nelson et al., 2007). Reactive responses are responses made rapidly to respond with prompt innovations or reactive transformations to minimize the damage from specific events in the short term and long term, whereas proactive responses represent long-term strategized processes that integrate new information as it manifests (Hill & Engle, 2013). A fundamental part of proactive responses is considered to be the active involvement of the individual, community, or society involved in the process. Adaptive capacity is not static, nor is adaptive capacity evenly distributed within populations or communities themselves (Berkes et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2004). In turn, making climate change part of a complex array of social-environmental pressures to which rural (and Indigenous) communities seek to cope and adapt. The literature on climate change adaptation contends that the reciprocal and social relations commonly found in agrarian societies are critical for dealing with hardships like climate change impacts and disasters (Adger, 2003a, b; Pelling, 1999; Ribot et al., 1996). Thereby implying that not only do agrarian and natural-resource dependent communities tend to face greater impacts and disparate vulnerabilities to climate change, but they also hold the social qualities and adaptive capacity to respond to climate change. As key examples, communities in the two case studies employ their own local resource governance systems, based on traditional and collective models. Though there is variation between the approaches in the two regions, including in the formal governance and local-level institutions.

If complex governance systems provide a combination of purposeful collective action and emergent phenomena resulting from self-organization processes and agency among a range of actors (Grecksch & Klöck, 2020), then local and customary institutions in Indonesia are a good example of these. They often provide structure and foster trust and norms of reciprocity for cooperation and coordinated actions, which are deeply tied to local notions of identity and social norms of cooperation (Dahal & Adhikari, 2008). Adat describes customary systems and people, encompassing most angles of life. The term has come to refer to the collective identity of various indigenous practices under the umbrella of custom (van Engelenhoven, 2021). From legal, religious, moral, political, and cultural aspects through to governing individual behaviors, to how families relate and the interrelations and intrarelations of the community and community members (Davidson & Henley, 2007). Adat prescribes a system of relation between people and the environment, covering most aspects of resource management (social, economic, and environmental) (Tyson, 2010). Adat conversely holds many meanings according to the context in which it sits. Used within and across communities to form collective management for local resources, Adat persists widely across Indonesia, determining local resource governance practices (Tyson, 2010).

Throughout Indonesia, alongside the customary institutions providing structure and fostering norms of reciprocity for cooperation and coordinated action, other examples of reciprocal and social relations can be found that are applicable to adaptative capacity. For example, Gotong royong, or collective action (Anwar et al., 2017) forms three tiers of community obligations alongside musyawarah (consensus; technically the basis for legislative decision-making) and koperasi (cooperatives; constitutionally the basis of the economy). These three socio-cultural forms of local governance or mutual assistance at the village level are also vital to adaptive capacity, remaining widespread and deeply rooted culturally (Bowen, 1986). Gotong royong, for example, has been widely associated in Indonesia’s disaster risk reduction and socio-cultural identity literature, as a key form of social capital interchangeable with resilience and adaptive capacity in a number of studies (Bowen, 1986; Ha, 2010; Kusumawardhani, 2014; Lukiyanto & Wijayaningtyas, 2020; Mardiasmo & Barnes, 2015; Slikkerveer, 2019; Suwignyo, 2019). Gotong royong refers to the principle of neighbors helping each other without the promise of anything in return (reciprocity) (Anwar et al., 2017). Gotong royong is considered mutual assistance, although the applications are varied and involve ideas mixed between obligation and the practice of reciprocity (Bowen, 1986). Common examples of applications are environmental protection or collaboration of local residents working together, volunteering to help neighbors and reconstructing local roads or village infrastructure (Anwar et al., 2017; Kusumawardhani, 2014). These forms of mutual exchange are also key to enacting collective responses and engaging the social relations and reciprocity needed for dealing with hardships such as climate change alike. These elements also form the basis for formal governance institutions such as Musrenbang, which is an amalgamation of Musyawarah Perencanaan Pembangunan. Musyawarah means communities coming together to resolve conflicts peacefully (rule by consensus), and Perencanaan Pembangunan means development planning (Sindre, 2012) to decide community priorities (Idajati et al., 2016). Musrenbang foundations, for example, are built on the tradition of community organizing in Indonesia that combines notions of traditional conflict resolution mechanisms for development planning, with multistakeholder consultation forums meant to encourage and promote community participation (Sindre, 2012).

These local traditional governance systems and structures were incorporated during the post-Suharto revision of national and local institutions in Indonesia. Legislation was altered to provide more access to village communities by utilizing traditional local systems of governance, to play a role within the planning and development that concerns them. In Adat areas, such as Maluku, a local governance configuration imported from the structure in JavaFootnote 5 had previously forced village administrations to incorporate the government system established under the Javanese regional and village government style throughout Indonesia. During the Suharto period, this amalgamation of the local governance system effectively disconnected the various customs and converged the diverse systems and mechanisms of authority held over natural resources (Batiran & Salim, 2020). Following the collapse of the New Order, as attempts to make planning more participatory were made (Purba, 2011), the role and function of the administrative system shifted toward a community, bottom-up direction. Greater local participation in decision making was supposed to be achieved in order to re-democratize processes and guarantee rights to land and resources for Indonesian civilians (Warren & McCarthy, 2009). Institutions (e.g., ronda, the community-neighborhood security system, or kerja bakti, a form of neighborhood social service) that had been previously utlized under Suharto to mobilize communities, instead reinterpreted, reappropriated, and redirected toward community purposes (Wilhelm, 2011). These changes repivoted local governance toward traditional systems intended to promote decentralization. While at the same time, this decentralization sought to overturn the nation-state approach to applying a uniform local governance model across the Indonesian archipelago that had been taken during the New Order period, which had erased cultural and geographically specific traditional governance institutions with varying success (Bebbington et al., 2006).

Community level governance was released from various regulations (and supervisions) post-Suharto, enabling a return to the practice of local customs within customary institutions, as local village-level institutions across Indonesia moved to combine formal and informal institutions. At local levels, these integrate with traditional systems of governance. In Haruku, for example, a hybrid system operates that includes national formal institutions, and also the local institutions of Negeri (the name in Maluku for village country, lands, or customary territory) and Sasi customary governance among aspects of the national system. Sasi is the customary law found throughout adat areas in Maluku, which enforces terms of governance and protection of natural resources guarding ecosystems through regulations, boundary controls, allocations of sustainable use periods or protection time period controls (Mantjoro, 1996; Soselisa, 2019).

4 Local Governance: Driving Adaptive Capacity Through Collective Response to Environmental Pressures, Conflict, and Change

Complex pressures facing rural areas in accessing and managing natural resource-based livelihoods force innovative collective action (Warren & McCarthy, 2009) mediating rural communities’ vulnerability to climate change and resilience (Dodman et al., 2014). Hence, collective management of natural resources has been crucial to sustaining lives and livelihoods on an ongoing basis, and in resilience of ever-present environmental pressures and threats. At the same time, for these reasons, the collective handling of environmental risks, pressures, and local governance of natural resources are considered crucial in addressing climate change impacts (Adger, 2003b). Widely throughout Indonesia, local communities, such as in Haruku and Kulon Progo, have been responding and adapting to ongoing and rapid environmental change and pressures for decades, utilizing collective approaches to local resource governance that are adaptive. One key exemplar being the role that the indigenous and agrarian movements, found widely throughout Indonesia, have played in securing access to land, locally determining resource governance through advocacy and various campaigns (Peluso et al., 2008). As part of ensuring access to resources, the emergence of a legitimizing discourse that has recurrently stressed environmental stewardship, cultural identification and attachment to place, has often formed part of securing land and resource (and thereby livelihood) access (Hall et al., 2011). For instance, through the use of indigeneity in asserting rights toward and the capacity to govern forest areas (Hall et al., 2011).

Legitimization plays a central role in collective mobilizations (Hall et al., 2011), allowing people to position themselves to acquire rights or resources (Karlsson, 2003; Li, 1996, 1999). Claims to land rights were increasingly made in the form of appealing to collective Adat rights following the fall of the New Order, with the rapid rise of social movements recognizing indigenous community and Adat rights (Muur, 2018; Muur et al., 2019). Masyarakat Hukum Adat (customary community law) can be proven as a claim to territories by linage as well as by those actively living under customary institutions and traditionsFootnote 6 (Bedner, 2016). Hence a resurgence of Adat local customary institutions (Davidson & Henley, 2007) arose, both in proliferation and the strength of customary Adat groups, alongside (local) nongovernment organizations, and ad-hoc community groups (Warren & McCarthy, 2009) to overcome discrepancies in land access and ownership. Agrarian movements also became more frequent as a path for autonomy and access to local government (Lund & Rachman, 2016). In this way, communities such as in Haruku and Kulon Progo, have been countering land pressures and conflicts, and exhibiting advocacy of their own resilience and agency by enhancing their access to resources (Li, 1996, 1999; Lund & Saito-Jensen, 2013; Platteau, 2004; Platteau & Abraham, 2002; Ribot, 2007).

This advocacy for legitimacy and rights of access to land (and marine) resources, has been routinely evident over decades in both case study contexts, as part of enabling and guarding community resilience in a number of ways. In Haruku, the Kewang as a customary institution have a long-running history of involvement and continue to be involved with government, non-government and civil organizations for advocacy on the role of customary governance and rights. In the lead up to the Maluku conflict (often referred to as the Maluku warsFootnote 7), Haruku faced environmental and resource access pressures. A large Indonesian mining company with foreign investment and backing from the central government (Batiran & Salim, 2020), secured state permits for gold mining exploration in the upper catchment areas of Learisa Kayeli River of Negeri Haruku. The exploration resulted in damage to parts of the upper river area of Negeri Haruku with flow-on consequences to the lower estuary. Traditional fish breeding grounds were damaged, while mining operations on the mountain rendered the river and drinking water supplies unpotable, and customary Adat practices (Sasi lompa) were forced to cease with the loss of the ecological systems. “They dug it up, they drilled it ... the soil became white like coconut milk. When they dug on the riverbank, it [tailings] were carried into the river and drifted down. Without knowing, the people here and below who use the water and the lompa fish were affected. Sasi lompa could not be held.” The infringements on Sasi managed area, spurred collective action and a resilient response from Haruku residents under the stronghold of the Kewang, who together put up substantial resistance. By aligning themselves with broader indigenous and environmental rights advocates, residents were able to draw on networks of support and alignment, and the local community was able to advocate their own resilience and agency in retaining access to their customary lands and resources. Closely aligned with a tight support network, they succeeded in ceasing the operations and damage being done to the water catchment and estuary under the mining exploration (Batiran & Salim, 2020). By pooling resources, residents were able to draw on the support of networks from indigenous peoples movements, building and gaining support from a network of NGOs, academics and Indigenous rights-advocacy groups such as Baileo Foundation and the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago – AMAN) and the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples Rights (Batiran & Salim, 2020). Head Kewang commented, “I brought legal experts from Unpatti [the local university], and they provided legal counseling for the community … because if the mine had a future, it would have been bleak for us, and we would have had to leave this village.”

Meanwhile, in Kulon Progo, the same strategies that have spurred resilience in cultivating productive agricultural systems and livelihoods in marginalised, or in unproductive conditions in a harsh coastal landscapes, have also ensured continued active engagement in adapting strategies for retaining land access. Conflict over land use has been heated over the last decade due to sand mining proposals for coastal agricultural lands. Farmer access to farming lands remains insecure for the area, as under the special region status, land management and ownership remain subject to the Sultan of Yogyakarta, rather than the national Government of Indonesia for areas equivocal to government or “crown” lands. Pakualaman Ground (PAG) or Tanah Pakualaman is a term for land held under the Duchy of Pakualaman, or the Sultanate of Yogyakarta. With the status of Pakualam Tanah Sultan, legal ownership is difficult for residents, who instead are granted only Magersari, or right of use. While residents own their houses on the land, maintaining access to land with this status is insecure. All nonprivate land areas formally held under crown land had been transferred to the Republic of Indonesia under the 1960 Basic Agrarian Law (BAL). These lands were allocated to be used for local communities and public land. However, in 2012, laws for the Yogyakarta District were changed, which altered the status of the Agrarian Law No.5/1960. In practice, this meant that vast tracts of lands used and occupied for generations by local communities prior to and since Indonesia’s Independence, were suddenly subject to seizure under Law No. 13 of 2012 concerning the Privileges of DIY (UUK). Numerous conflicts have been recorded throughout the Yogyakarta Province concerning evictions from land following this law change.Footnote 8 The most contentious have included industry parks, mining operations, the international airport and other private-investment commercial operations (hotels, apartments). Coastal farmlands in Kulon Progo are earmarked for large-scale commercial projects (e.g., iron sand mining). At the same time, the Kulon Progo district government is in an impasse as they cannot build infrastructure to support the activities of the residents on these sites because the area is under status as a contract area (Hernawan et al., 2021). Until now, farmers in the area have resisted eviction, partially due to legal rights remaining unclear, as well as ongoing viability issues and investor pull-outs on the proposed developments. Efforts have also been sustained within social networks and collective action, such as farmer forums and networks for knowledge sharing and support (farmer to farmer).

At the same time, precarious access has merged with ongoing pressures and conflict to spur enduring strategies to adapt to harsh environmental conditions through the ongoing need to secure access to land and resources. Aside from active resistance and strategies deployed to retain access to farmlands, the coastal villages in Kulon Progo are widely known for the strategies employed in farming land unfavourable for agricultural due to harsh coastal conditions. The villages engaged in farming on the coastal area of Kulon Progo have a history of local innovations in responding to change and non-favourable agricultural conditions, including strategies for adaptation to climate change conditions and impacts. The coastal farming areas of Kulon Progo (Desa Garongan, Kulon Progo, Barangan, Pleret and Bugel) have sustainably farmed in harsh coastal conditions of sandy soils, salinity, high winds, and limited water access, after converting the area to a high yielding agricultural area. The cultivation of the upper sand dunes by farmers along this small section of coastline consistently boasts Indonesia’s largest chili crop, while other crops are also cultivated. Chilli has been adapted to grow through the wet season, when other areas of Indonesia are unable to produce, in turn, gaining higher price values as a result of the produce. Studies on the area have shown highly innovative adaptive farming techniques employed (Dinarti et al., 2013; Supriyanto et al., 2012). In particular, innovative agricultural livelihood diversification is based around collective management systems (Raya, 2014). These systems were found to emphasize reciprocal social relations used to foster local resource governance conducive to the ongoing adaptation of land management, which is also applicable to climate change (Supriyanto et al., 2011, 2012). The latter study particularly highlights coastal farmers’ in Kulon Progo’s ability to control environmental, physical, economic, human, and political forms of capital to build up an active, innovative, and adaptive farming community in the coastal area. Notably, these systems have enabled an agricultural livelihood-based community to flourish in a sandy coastal environment utilized as highly productive agricultural land.

Since the early 1980s, the farmers expanded the land available to them by cultivating the coastline area, utilizing a mix of local indigenous knowledge informing land management practices and ingenuity driven by scarce available resources – in order to farm in sand on the wind-swept coastal area. Innovative strategies have been formulated in response to the harsh environmental conditions in which to generate livelihoods, collective action has formed as a way of sustaining livelihoods. These innovations have incorporated the use of watering technology, merging techniques to intensify cropping options (wells, pumps, drip enhanced efficiency, piping); adaptation of techniques such as companion planting, permaculture, composting, on-site organic manure fertilisers); diversification and increased biodiversity of cropping (e.g. buffering from reliance and market dependence, windbreak cropping).

Social networks and collective action also form a large aspect to enabling this, from streamlining trial and error learning (neighbors replicating successes), farmer forums and networks were also developed for knowledge sharing and support (farmer to farmer). These have helped with strategic actions such as adapting seed varieties and cultivars, and the establishment of cooperatives to determine marketing and pricing collectively, as well as pooling transport logistics, and community systems for managing shared resources between farmers (e.g., windbreak vegetation and water resources). These actions extend to responses to market conditions (formulating cooperatives to ensure reliable market price for produce), as well as for ensuring climate change impact driven issues, such as growing incidence of pests, are controlled through group mechanism calendar that collectively governs periods for harvesting in order to eliminate fungus and pests from ruining all crops. Amongst other examples, farmers agree, regardless of whether they still have remaining produce to harvest, to pull out chili plants on the agreed dates so that the soil can be left ‘to rest’, and pests are unable to take a hold.

5 Innovating Adaptive Capacity to Climate Change: Collective Local Governance

In both case studies, overcoming environmental pressures, conflict and change through local governance approaches have been important to driving adaptive capacity, both generally, and to climate change for several reasons. The drive in securing access and sustainable use of resources through collective responses has been critical in also driving the factors that support climate change resilience and the adaptive capacity of residents in both cases. For Masyarakat Adat in Haruku, adaptive capacity and ways to respond to climate change have primarily centred on customary cultural and resource land management practices to guard local ecosystem integrity. These practices guard the sustainability of local ecosystem integrity and offer a diversity of options for livelihood security. Customary rules mean that resources are therefore used most efficiently, usefully and are maintained within ecological bounds sustainably (e.g. young fruit in the forest should not be taken so that they have the opportunity to first grow and produce seed). The customary practices guard Negeri ecosystem integrity, by ensuring the resilience of the environmental systems are more robust in facing climate change conditions, including the diversity of food systems.

Sasi is the traditional community-based resource governance system of Haruku. Present throughout Maluku, Sasi is found from the northern Islands of Halmahera, Ternate, Buru, Seram, Ambon and Haruku, to the south and southeast of Banda, Kei and Aru, as well as throughout areas of Papua. Although Haruku is one of the remaining villages in the Maluku islands that maintains and practices the tradition of Sasi. Sasi provides guidance and sanctions enforced by KewangFootnote 9 as the rules of the Negeri. Sasi stipulates the management of agroforestry and marine and fishery resources and is widely considered one of the few remaining long-enduring community-based resource management systems in Asia (Novaczek et al., 2001). Sasi is also the longest enduring traditional community-based coastal resource management system in Southeast Asia. It is dated to have been the system of use in the area since the sixteenth century – in providing guidance both for conservation practices and social issues and essentially maintaining natural food resources (Zerner, 1994). Sasi is endowed as providing the system of customary law governing social and environmental resources, both terrestrial and marine, throughout the Island of Haruku (Zerner, 1994). Sasi as customary law is set out in three areas – firstly, as regarding the governance of resources relating to conservation and protection of the environment and environmental resources. Secondly, in social customs, habits and values, and thirdly, in defining the implementation of the laws and their enforcement. Ultimately employing methods of timing and space in order to regulate access to resources and territories (Novaczek et al., 2001). In turn, these effectively maintain a sustainable ecological, livelihood, and conservation equilibrium (e.g., customary forest conservation, fish stock sustainability practices).

Land in Haruku is allocated as customary land, and while the land is inherited within families, most of the land within the Negeri is allocated as customary land and therefore shared. Kewang serve as representatives of the customary law and traditions of Sasi, found throughout Central Maluku, responsible for controlling environmental management of all resources in the village domain, especially during the Sasi (control or protection time periods) (Soselisa, 2019). The Kewang designated through family linage are selected members from family clans to guard and enforce the terms of customary Law or Sasi – controlling governance and protecting natural resources, both land and marine. In particular, Kewang hold responsibility for periods in which resources are protected or guarded to ensure their sustainability. The Kewang are also elected to discuss village economy, the coordination of village economic and livelihood aspects, including infringements of Sasi regulations, and boundary controls with neighbouring villages, including the patrols of (common) natural resources, both marine and terrestrial (Mantjoro, 1996; Zerner, 2014). Kewang also monitor and manage conflict, such as when someone is caught violating the Sasi in the petuanan area, the Kewang will hold a hearing and decide sanctions.

Sasi comprehensively guides everything (Zerner, 1994), to ensure that all-natural food systems are well-managed and sustained. For example, Sasi ensures that the forest is maintained sustainably, prohibiting the young fruits from being taken so that they can reproduce first. Sasi also ensures that the lompa fish are not taken until they have completed their breeding cycle and are of a certain size. Sasi, when closed, means that no harvest of that resource can take place whatsoever during the time. It is signalled by certain symbolic signs placed in front or on the resource (e.g. tree, fruit, bush, fish type) being protected (Zerner, 1994). Sasi rules also form part of the vow of the ancestors (ina ama), which are maintained continuously to become the norms, values and practices among community life (Batiran & Salim, 2020). Although according to Kewang, Sasi is constantly being adapted and updated to remain relevant and appropriate and that the laws are not fixed.

Diversity and timing have been significant for maintaining livelihoods and has been built over generations in Haruku. Before climate change, variations affecting seasons and the predictability of rain and dry periods, along with impacts from increased heat and storms and inundation timing, were balanced carefully. For these reasons, the collective responses to environmental pressures, conflict and change are therefore vital also in driving adaptive capacity to climate change, with maintaining access to resources and the sustainable use of those resources being vital to local communities’ resilience to climate change. “We have [traditional] staples based on sago – bapeda, as well as kasbi [casava] and others. Kasbi isn’t affected by pests, variable rains, storms or waves, or earthquakes. No one goes hungry also because we also all share. We have double livelihoods that we can swap between if the conditions are not right to go to the sea because of either climate change or earthquakes and the threat of a tsunami.”

In Haruku, for example, although Sasi protects and maintains fish stocks, the areas within the Haruku Negeri boundaries are regularly robbed, putting fish numbers in jeopardy. Despite clear boundary demarcations, disputes exist over access and use, mainly over commonly held resources, such as marine resources. Fishing trawlers and illegal fishing are ongoing within the area. Whereas Negeri Haruku and Haruku village are bound by Sasi regulations on fish catch numbers and methods, neighboring villages use fish bombing or dynamite fishing methods. “Fish are difficult to come by in the neighboring village because their habit is to use fish bombing [dynamite fishing]. Whereas here, you can just be sitting on the seawall and catch fish.” To overcome issues such as illegal fishing and use of destructive techniques like dynamite fishing throughout the Sasi protected fish grounds, the Kewang run intercountry cooperation, drawing on and pooling networks to collectively overcome environmental resource pressures and conflicts. “We work together to protect the coast so that people can no longer come with fish bombs to destroy the coral reefs.”

Kulon Progo farmers, according to the generation, rely on the local customary indigenous system of Pranata Mangsa. Pranata mangsa is calendar system used in farming practices in Java that follow nature as a guide for farming and fishing, with a relationship focused on environmental cycles (Retnowati et al., 2014). The land cultivation utilizes knowledge informing land management practices (e.g., lunar-solar calendar in dictating farming practices, known as pranata mangsa), as well as the innovation from ingenuity in scarce resource access that have gradually allowed for sophisticated farming to develop in sand soil on a wind, swept coastline. The pranata mangsa calendar uses nature as a guide for farming and fishing, within a relationship focused on environmental cycles (Retnowati et al., 2014). Pranata Mangsa follows the circulation of the sun over the year using aspects of phenology and signaling to guide farming activities, as well as preparation for disasters (such as drought, disease outbreaks, floods, pests) that may occur at certain times. The calendar system ascribes timings to the seasons – such as dry season, the transition season before the rainy season, the rainy season and the transition at the end of the rainy season, all with a certain number of days each between them. Pranata Mangsa is a system used widely throughout Java as a local calendar and planning method for agriculture and fishing but dramatically shifting under climate change. Part of which includes reading signs from nature, known as titen, and built into farmers’ process of observing agro-meteorological changes by observing, recording, analyzing, and evaluating existing knowledge for adaptation. With each of these signals there are particular times for planting and harvesting of certain crops (Retnowati et al., 2014).

Interlinked with these systems and ongoing innovations, farmers say they are now continuously shifting around the climate although they have always planned their activities around the shifting of the seasons. “We were already adjusting to the climate from that of our ancestors. So, the pattern of the planting is already a season of certain months it is a type of plants. It means that the agriculture sector has also adjusted to climate change. If it was before there was already the pattern.” However, the timescales for shifting have altered, and they are now left to shift dramatically as rainfall and season patterns vary. “Farmers here are already sensitive to anticipate climate change.” For the increased heat periods, for example, farmers start earlier to water their crops so that the water can permeate, and then water again in the evenings. “It used to be in one day that we are watering it two-three hours may be enough. But if it is now at least every four hours to five hours or even six hours.” Farmers say they change the system so that they can retain moisture for more protracted timeframes, by using mulch, as well as continually planting windbreaks and trees to break up the sun, dry wind, and heat. Locals claim that the extreme weather variation has resulted in more crop disease, particularly fungus and that they have also lost produce regularly. So, the area collectively coordinates plantings and uses agreements on dates as to when certain crops will be harvested and pulled out in order to minimize the risk of disease for all. A period of “sanitation” is undergone, mutually, between all farmers collectively so that the chain of disease is broken. “To neutralize the PH of the soil, we use dolomite and rotate the crops. Using intercropping, for example, we will create a wedge there with long beans, then there with peanuts and vegetables. To break up the chance of pest incidence.”

6 Conclusion

Climate change is significantly impacting local communities throughout Indonesia dependent on access to ecosystems and weather-dependent resources. Nevertheless, local communities have been responding and adapting to ongoing and rapid environmental change and pressures for decades, utilizing collective approaches to local resource governance that are adaptive. Local resource governance innovates and engages strategies of adaptation to drive the ability to deal with environmental pressures, conflict, and change. These methods of responding and adapting to change are also crucial in how climate change responses are formed.

This chapter has briefly shown through case studies how local communities govern, innovate, and engage strategies of adaptation to change to land-use pressures and environmental change. The case studies in this chapter provide examples of how local-level community customary institutions in Indonesia foster norms of reciprocity for cooperation and coordinated actions. These collective mechanisms are crucial in the reciprocal and social relations needed for dealing with an array of hardships arising from pressure, conflict, and change and including climate change impacts. These examples provide insights into the collective handling of environmental risks and local governance of natural resources that correlate with the ways local communities can govern, innovate, and engage adaptation strategies to deal with environmental stresses and change including climate. By being active in their resilience and adaptation strategies to other (nonclimate) types of social and environmental pressures and change, these cases have shown the local agency, self-determination, and collective action that is prominent in driving adaptive capacity to environmental pressures and change within the local resource governance.

Notes

- 1.

The Daerah Istimewah Yogyakarta (DIY) is a Special Administrative District since 1945, headed by a Sultanate.

- 2.

Where verbatim quotes are included in this article, these are translated from either Javanese or Indonesian languages, and Ambon or Haruku dialects, with some variation in the interpretations.

- 3.

It should be distinguished that the poverty line defined by the Indonesian government is substantially lower than other measures (e.g., the World Bank poverty line uses US$1.25 daily rate). In 2016, the Government of Indonesia defined the national poverty line as a monthly per capita income of IDR354, 386 (equivalent to US$26). This is much lower than poverty lines applied globally. Using global indicators, the rate is much higher.

- 4.

The Consortium for Agrarian Reform, for example, noted that for 2017, as many as 659 active agrarian conflicts were disputing a total land size area as large as 520,491.87 acres and including at least 652,738 households (Handoko et al., 2019).

- 5.

In rural village settings in Java, the responsibility for the community falls predominately to the RT, RW, Dukuh, and Kelurahan institutions. While farmers in the Java case study have formed their own clusters for governing local resources relating to farming between them, which overlaps between the RT and RW levels, as well as taking in the cooperative and alliances formed between coastal farmers. Formally, each cluster of 50–80 households is broken into the formal institution of rukun tetengga (RT) (Simarmata et al., 2013). Rukun tetengga roughly translates as “neighborhood association.” Each rukun tetengga, or RT, holds a formal leader. The RT unit and its appointed head (elected via a process of voting, by each registered resident), then, sit under the larger grouping of rukun warga (RW). In areas where there is no longer the appointed RW grouping, the RT grouping sits directly under the Dukuh (the equivalent of a hamlet), and its (elected) appointed head. Rukun warga (RW) is a division of territory in Indonesia below the Dusun or Lingkungan. Rukun warga is not included as a division of government administration, and its formation is passed through a community meeting of citizens, in the same process for the RT grouping. This unit consists of several RT groupings and their heads. RT and RW institutions tend to be more engaged within community life and have an administrative function in forming the neighborhood (Yuliastuti et al., 2015). In general, however, the functions of RT and RW are not just related with the kinship of community. The RT and RW groupings coordinate community activities and bridge the relationship between village communities and the government (in this case is the Kelurahan or sub-district). In other words, structurally RT and RW are the lower administrative organizations dealing directly with the public. RT organizations have a strategic role in relation to community social activities, and in linking administrative affairs and social issues (Yuliastuti et al., 2015). The next unit grouping level up is the Kelurahan, which comprises of several Dukuh and RW groups. From Kelurahan sits the Kabupaten, the Kecamatan and then a mayor. With non-elected, government appointed heads, these then feed up to the provincial and national governments (Simarmata et al., 2013). The Kelurahan operate as the smaller instrument of Kabupatens, Kotamadya, or Kota administrasi, below the Kecamatan level. In terms of formal government administrations, the Kelurahan is the smallest organizational unit and the closest government administration institution to village community life (Yuliastuti et al., 2015).

- 6.

Controversially, the right to aval under hakulayat cannot be used against state interest under Article 3, or be registered.

- 7.

In Maluku, conflict erupted during the post-Suharto period from 1999 into 2004/2005, often referred to as the Maluku wars.

- 8.

For example, (1) construction of the International Airport in Kulonprogo; (2) mining of iron sands and construction of a steel factory in Kulonprogo; (3) eviction of residents’ settlements in Parangkusumo; (4) eviction of shrimp ponds in Parangkusumo; (5) pegging of sultan ground (SG) on state land in Parangkusumo; (6) fixing SG’s land on community-owned land in Mancingan Parangtritis; (7) confiscation of land rights through changing the status of building use rights on Jalan Solo Kotabaru; (8) eviction of a group of residents in Suryowijayan; (9) threats of eviction of street vendors under the pretext of SG’s land in Gondomanan; (10) revitalization of the Kepatihan Office which resulted in eviction in Suryawijayan; (11) seizure of village land through reversing the name of village land certificates throughout DIY; (12) racial/ethnic discrimination through the prohibition of land ownership rights throughout DIY; (13) refusal to extend building use rights in Jogoyudan, Jetis; (14) refusal to apply for land title certificates in Blunyahgede; (15) construction of apartments in densely residential areas on Jalan Kaliurang km 5; (16) withdrawal of property rights certificates under the pretext of renewing certificates in Mantrijeron; (17) seizure of land rights through cancellation of land ownership rights in Pundungsari; (18) seizure of state and citizen land in the name of controlling SG land and tourism throughout Gunungkidul; (19) forced eviction and demolition of community stalls under the pretext of SG land (Saroh, 2016).

- 9.

Kewang are the custodians of Sasi (customary law) in Haruku (and throughout some other islands of Maluku).

References

Adger. (2003a). Social aspects of adaptive capacity. In J. B. Smith, R. J. T. Klein, & S. Huq (Eds.), Climate change, adaptive capacity and development (pp. 29–49). Imperial College Press and distributed by World Scientific Publishing Co.. https://doi.org/10.1142/9781860945816_0003

Adger. (2003b). Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Economic Geography; Oxford, 79(4), 387–404.

Adger, W. N., Agrawala, S., Mirza, M. M. Q., Conde, C., O’Brien, K., Pulhin, J., Pulwarty, R., Smit, B., Takahashi, K., Enright, B., Fankhauser, S., Ford, J., Gigli, S., Jetté-Nantel, S., Klein, R. J. T., Pearce, T. D., Shreshtha, A., Shukla, P. R., Smith, J. B., … Hanson, C. E. (2007). Assessment of adaptation practices, options, constraints and capacity. In Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (p. 28). Cambridge University Press.

Anwar, H. Z., Yustiningrum, E., Andriana, N., Kusumawardhani, D. T. P., Sagala, S., & Mayang Sari, A. (2017). Measuring community resilience to natural hazards: Case study of Yogyakarta province. In R. Djalante, M. Garschagen, F. Thomalla, & R. Shaw (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction in Indonesia: Progress, challenges, and issues (pp. 609–633). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54466-3_25

Ayers, J. (2010). Understanding the adaptation paradox: Can global climate change adaptation policy be locally inclusive? London School of Economics and Political Science. http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/393/1/Ayers_Understanding%20the%20Adaptation%20Paradox.pdf

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2016). Rethinking case study research: A comparative approach. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315674889. eBook ISBN9781315674889.

Batiran, K., & Salim, I. (2020). A Tale of Two Kewangs: A comparative study of traditional institutions and their effect on conservation in Maluku. Forestry and Society, 4(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.24259/fs.v4i1.8186

Bebbington, A., Dharmawan, L., Fahmi, E., & Guggenheim, S. (2006). Local capacity, village governance, and the political economy of rural development in Indonesia. World Development, 34(11), 1958–1976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.025

Bedner, A. (2016). Indonesian land law: Integration at last? And for whom? In J. F. McCarthy & K. Robinson (Eds.), Land and development in Indonesia: Searching for the people’s sovereignty (pp. 63–88). ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/land-and-development-in-indonesia/indonesian-land-law-integration-at-last-and-for-whom/814ED122711109DF92EFF35F6996CEAA

Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Folke, C. (2008). navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bowen, J. R. (1986). On the political construction of tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Studies, 45(3), 545–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/2056530

BPS. (2016). Indonesia – National Socio-economic survey 2016 March (National Socio-Economic Survey (SUSENAS)). Data from Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS). https://microdata.bps.go.id/mikrodata/index.php/catalog/768

BPS. (2020). Badan Statistik Indeks Pembangunan Manusia (Central Bureau of Statistics – Social and population – Employment). Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS)/ Central Burea of Statistics, Indonesia.

Dahal, G. R., & Adhikari, K. P. (2008). Bridging, linking, and bonding social capital in collective action: The case of Kalahan Forest Reserve in the Philippines (No. 577-2016–39220). AgEcon Search. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.44352

Dasgupta, P., Morton, J., Dodman, D., Karapinar, B., Meza, F., Rivera-Ferre, M. G., Toure Sarr, A., & Vincent, K. E. (2014). Rural areas. In C. Field & V. Barros (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: Vol. A (pp. 613–657). Cambridge University Press. https://gala.gre.ac.uk/id/eprint/14369/

Davidson, J., & Henley, D. (2007). The revival of tradition in Indonesian Politics: The deployment of Adat from colonialism to indigenism. Routledge.

Dinarti, S. I., Wastutiningsih, S. P., Subejo, S., & Supriyanto, S. (2013). Kecerdasan Kolektif Petani Di Lahan Pertanian Pasir Pantai Kecamatan Panjatan Kabupaten Kulon Progo (Collective innovation of farmers in Pasir Pantai Farming District, Panjatan District, Kulon Progo Regency). Agro Ekonomi, 24(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.22146/jae.18328

Djalante. (2018). NHESS – Review article: A systematic literature review of research trends and authorships on natural hazards, disasters, risk reduction and climate change in Indonesia. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 18, 1785–1810. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-1785-2018

Dodman, D., Karapinar, B., Meza, F., Rivera-Ferre, M., Sarr, A., & Vincent, K. (2014). Rural areas. In C. Field, V. Barros, D. Dokken, M. March, T. Mastrandrea, T. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. Ebi, Y. Estrada, R. Genova, B. Girma, E. Kissel, A. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. Mastrandrea, & L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 613–657). Cambridge University Press.

EMDAT. (2020). Emergency events database (EM-DAT) (The International Disaster Database) [Custom request]. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain). www.emdat.be

Ford, J. D., McDowell, G., Shirley, J., Pitre, M., Siewierski, R., Gough, W., Duerden, F., Pearce, T., Adams, P., & Statham, S. (2013). The dynamic multiscale nature of climate change vulnerability: An inuit harvesting example. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(5), 1193–1211. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.776880

Gallopín, G. C. (2006). Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004

Gaspersz, E. J., & Saiya, H. G. (2019). Pemetaan Kearifan Lokal Budaya Sasi Di Negeri Haruku Dan Negeri Kailolo, Pulau Haruku, Kabupaten Maluku Tengah (Mapping Of The Local Awareness Of The Sasi Culture In Haruku State And The Country Of Kailolo, Haruku Island, Central Maluku District). Seminar Nasional Geomatika, 3, 107. https://doi.org/10.24895/SNG.2018.3-0.933

Gibson, L., Widiastuti, D., Maulana, A., Nikmah, S., Bahagijo, S., Patria, N., Bernabe, M., Hardoon, D., Galasso, N., Jacobs, D., Marriot, A., Marriotti, C., & Kamal-Yanni, M. (2017). Towards a more equal Indonesia: How the government can take action to close the gap between the richest and the rest (p. 48) [Briefing paper]. Oxfam GB for Oxfam International. https://oi-files-d8-prod.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/bp-towards-more-equal-indonesia-230217-en_0.pdf

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05292-5.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1987). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (1st ed.). Routledge.

Grecksch, K., & Klöck, C. (2020). Access and allocation in climate change adaptation. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20(2), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09477-5

Ha, W. (2010). Social capital and crisis coping in Indonesia. In R. Fuentes-Nieva & P. A. Seck (Eds.), Risk, shocks, and human development: On the brink (pp. 284–309). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230274129_12

Hall, D., Hirsch, P., Li, T., & Challenges of the Agrarian Transition in Southeast Asia (Project). (2011). Powers of exclusion: Land dilemmas in Southeast Asia. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Hallatu, T. G. R., Palittin, I. D., Supriyadi, Yampap, U., Purwanty, R., & Ilyas, A. (2020). The role of religious sasi in environmental conservation. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environ. Sci, 473, 012082. IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/473/1/012082

Handoko, W., Larasati, E., Pradhanawati, A., & Santosa, E. (2019). Why land conflict in rural Central Java never ended: Identification of resolution efforts and failure factors. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 11–23.

Hernawan, A., Arumingtyas, L., Ricky P. D. M., Hasibuan, S., & Purnomo Edi, C. (2021). Deru Patok Tanah ‘Istimewa’, Petani akan Terus Bertahan dan Menanam (The fight of ‘special’ land stakes, farmers will continue to survive and farm) [By the Agrarian Coverage Collaboration Team on 19 September 2021]. Mongabay.Co.Id. https://www.mongabay.co.id/2021/09/19/deru-patok-tanah-istimewa-petani-akan-terus-bertahan-dan-menanam-4/

Hill, M., & Engle, N. L. (2013). Adaptive capacity: Tensions across scales. Environmental Policy and Governance, 23(3), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1610

Hinkel, J. (2011). “Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity”: Towards a clarification of the science–policy interface. Global Environmental Change, 21(1), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.08.002

Idajati, H., Pamungkas, A., Kukinul, S. V., Fadlillah, U., Firmansyah, F., Nursakti, A. P., & Pradinie, K. (2016). Increasing community knowledge of planning process and online Musrenbang process in Rungkut District Surabaya. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 227, 493–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.105

IPCC. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Ireland, P., & McKinnon, K. (2013). Strategic localism for an uncertain world: A postdevelopment approach to climate change adaptation | Kopernio. Geoforum, 47, 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.01.005

Karlsson, B. G. (2003). Anthropology and the ‘Indigenous Slot’: Claims to and Debates about Indigenous Peoples’ Status in India. Critique of Anthropology, 23(4), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X03234003

Kusumawardhani. (2014). Nilai Gotong Royong sebagai Modal Sosial dalam Pengurangan Risiko Bencana Alam: Kasus Sleman dan Bantul, Masyarakat Tangguh Bencana: Pendekatan Sosial Ekonomi (The value of mutual cooperation as social capital in reducing risk natural disasters: Cases of Sleman and Bantul, disaster resilient communities: Socio-economic approach). In H. Z. Anwar (Ed.), Tata Kelola dan Tata Ruang (Spatial planning governance) (1st ed.). Pusat Penelitian Geotecknologi LIPI (LIPI Geotechnological Research Center).

Li, T. M. (1996). Images of community: Discourse and strategy in property relations. Development and Change, 27(3), 501–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1996.tb00601.x

Li, T. M. (1999). Compromising power: Development, culture, and rule in Indonesia. Cultural Anthropology; Washington, 14(3), 295–322. http://dx.doi.org.virtual.anu.edu.au/10.1525/can.1999.14.3.295

Lukiyanto, K., & Wijayaningtyas, M. (2020). Gotong Royong as social capital to overcome micro and small enterprises’ capital difficulties. Heliyon, 6(9), e04879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04879

Lund, & Rachman, N. (2016). Occupied! Property, citizenship and peasant movements in rural Java. Development and Change, 47(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119384816.ch6

Lund, J. F., & Saito-Jensen, M. (2013). Revisiting the issue of elite capture of participatory initiatives. World Development, 46, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.028

Mantjoro, E. (1996). Traditional management of communal-property resources: The practice of the Sasi system. Ocean and Coastal Management, 32(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(96)00013-0

Mardiasmo, A., & Barnes, P. (2015). Community response to disasters in Indonesia: Gotong Royong; a double edged-sword. In P. Barnes & A. Goonetilleke (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th annual international conference of the international institute for infrastructure renewal and reconstruction (pp. 301–308). Queensland University of Technology. http://digitalcollections.qut.edu.au/2213/

Martin, P. Y., & Turner, B. A. (1986). Grounded theory and organizational research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/002188638602200207

McCarthy, J. F. (2017). Land and development in Indonesia. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc.

McCarthy, J. F., & Robinson, K. (2016). Land, economic development, social justice and environmental management in Indonesia: The search for the people’s sovereignty. In J. F. McCarthy & K. Robinson (Eds.), Land and development in Indonesia: Searching for the people’s sovereignty (pp. 1–32). ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/land-and-development-in-indonesia/land-economic-development-social-justice-and-environmental-management-in-indonesia-the-search-for-the-peoples-sovereignty/964B20CE91549FD9C5D0BF4625331D04

Mony, A., Satria, A., & Kinseng, R. A. (2017). Political ecology of Sasi Laut: Power relation on society-based coastal management. Journal of Rural Indonesia [JORI], 3(1) Retrieved from http://ejournal.skpm.ipb.ac.id/index.php/ruralindonesia/article/view/30

Muur, W. V. D. (2018). Forest conflicts and the informal nature of realizing indigenous land rights in Indonesia. Citizenship Studies, 22(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2018.1445495

Muur, W. V. D., Vel, J., Fisher, M. R., & Robinson, K. (2019). Changing indigeneity politics in Indonesia: From revival to projects. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 20(5), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2019.1669520

Myers, M. D. (2009). Qualitative research in business and management. SAGE. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/asi/qualitative-research-in-business-and-management/book244733

Nelson, D. R., Adger, W. N., & Brown, K. (2007). Adaptation to environmental change: Contributions of a resilience framework. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 32(1), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.32.051807.090348

Novaczek, I., Harkes, I. H. T., Sopacua, J., & Tatuhey, M. D. D. (2001). Institutional analysis of Sasi Laut in Maluku, Indonesia. ICLARM. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/30324

Pelling, M. (1999). The political ecology of flood hazard in urban Guyana. Geoforum, 30(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00015-9

Peluso, N. L., Afiff, S., & Rachman, N. F. (2008). Claiming the grounds for reform: Agrarian and environmental movements in Indonesia. Journal of Agrarian Change, 8(2–3), 377–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2008.00174.x

Platteau. (2004). Monitoring elite capture in community-driven development. Development and Change, 35(2), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2004.00350.x

Platteau, & Abraham, A. (2002). Participatory development in the presence of endogenous community imperfections. The Journal of Development Studies, 39(2), 104–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331322771

Purba, R. E. (2011). Public participation in development planning: A case study of Indonesian Musrenbang. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences: Annual Review, 5(12), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.18848/1833-1882/CGP/v05i12/51964

Raya, A. B. (2014). Farmer group performance of collective chili marketing on sandy land area of Yogyakarta Province Indonesia. Asian Social Science, 10(10), 1. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n10p1

Retnowati, A., Anantasari, E., Marfai, M., & Dittman, A. (2014). Environmental ethics in local knowledge responding to climate change: An understanding of seasonal traditional calendar PranotoMongso and its Phenology in Karst Area of GunungKidul, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 20, 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.095

Ribot. (2007). Representation, citizenship and the public domain in democratic decentralization. Development, 50(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100335

Ribot, J. C., Magalhães, A. R., & Panagides, S. (Eds.). (1996). Climate variability, climate change and social vulnerability in the semi-arid tropics. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511608308

Saroh, M. (2016). Warga Terdampak Penggusuran Gugat UU Keistimewaan Yogyakarta (Residents Affected by Evictions Sue - Yogyakarta Privileges Law). tirto.id. https://tirto.id/warga-terdampak-penggusuran-gugat-uu-keistimewaan-yogyakarta-bLm8

Simarmata, H. A., Sianturi, H. C. J. A., & Yudono, K. (2013, June 31). Measuring Vulnerability: Lesson from vulnerable groups along the example of Kampongs in North Jakarta. Proceedings of the Resilient Cities 2013 Congress: Urban Resilience and Adaptation. Resilient Cities 2013 congress, Bonn, Germany.

Sindre, G. M. (2012). Civic engagement and democracy in post-Suharto Indonesia: A review of Musrenbang, the Kecamatan development programme, and labour organising. PCD Journal, 1–40.

Slikkerveer, L. J. (2019). Gotong Royong: An indigenous institution of communality and mutual assistance in Indonesia. In L. J. Slikkerveer, G. Baourakis, & K. Saefullah (Eds.), Integrated community-managed development: Strategizing indigenous knowledge and institutions for poverty reduction and sustainable community development in Indonesia (pp. 307–320). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05423-6_14

Soselisa, H. L. (2019). Sasi Lompa: A critical review of the contribution of local practices to sustainable marine resource management in Central Maluku, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 339, 012013. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/339/1/012013

Supriyanto, Herianto, A. S., & Wastutiningsih, S. P. (2011, December 8). Modal sosial komunitas petanti lahan pasir pantai Kecematan Panjatan Kabupaten Kulon Progo (Social community model in the coastal sand area of Panjatan Subdistrict, Kulon Progo Regency). Proceeding of the National Seminar on the Research Results of the Socioeconomics Department in Yogyakarta. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Hasil Penelitian Jurusan Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian di Yogyakarta.

Supriyanto, Subejo, S., Herianto, I. A. S., Wastutiningsih, S. P., Dinarti, S. I., & Winanti, L. D. (2012). Strategi Adaptasi Petani Terhadap Perubahan Iklim. PINTAL.

Suwignyo, A. (2019). Gotong royong as social citizenship in Indonesia, 1940s to 1990s. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 50(3), 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022463419000407

Tyson, A. D. (2010). Decentralization and adat revivalism in Indonesia: The politics of becoming indigenous. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203849903

van Engelenhoven, G. (2021). From indigenous customary law to diasporic cultural heritage: reappropriations of adat throughout the history of Moluccan postcolonial migration. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law – Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 34(3), 695–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09781-y

Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2). http://www.jstor.org/stable/26267673

Warren, C., & McCarthy, J. F. (2009). Community, environment and local governance in Indonesia: Locating the commonweal. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/anu/detail.action?docID=1024674

Wilhelm, M. (2011). The role of community resilience in adaptation to climate change: The urban poor in Jakarta, Indonesia. In K. Otto-Zimmermann (Ed.), Resilient cities (pp. 45–53). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0785-6_5

World Bank. (2020, April). Indonesia overview. The World Bank in Indonesia. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/overview

Yuliastuti, N., Alie, J., & Soetomo, S. (2015). The role of community institutions “Rukun Tetangga” in social housing, Indonesia. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5, 44–52.

Zerner, C. (1994). Through a green lens: The construction of customary environmental law and community in Indonesia’s Maluku Islands. Law and Society Review, 28(5), 1079–1122. https://doi.org/10.2307/3054024

Zerner, C. (2014). Through a green lens: The construction of customary environmental law and community in Indonesia’s Maluku Islands. Law and Society Review, 28(5), 1079–1122. https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814789339-044

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Turner-Walker, S. (2023). Local Resource Governance: Strategies for Adapting to Change. In: Triyanti, A., Indrawan, M., Nurhidayah, L., Marfai, M.A. (eds) Environmental Governance in Indonesia. Environment & Policy, vol 61. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15904-6_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15904-6_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15903-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15904-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)