Abstract

It has been more than 5 years since the Paris Agreement was ratified, while the progress to limit the increase in global temperature to well below 2 °C above preindustrial levels is questionable. Addressing climate change cannot be separated from economic and political issues, leading to an emergence of global discourses about the appropriate means for a sustainable transformation. Although the green economy has received criticisms, such a concept is a “popular” vision to balance economic, social well-being, and ecological goals. However, the Covid-19 pandemic, which has no clear ending period, significantly impacts the economy and threatens climate actions. This chapter aims to analyze the fate of climate actions in Indonesia. We employ a crisis management framework to provide insights about governing climate change under the Covid-19 pandemic while seizing the opportunities to achieve the climate target. Unlike previous crises, the Covid-19 pandemic should be treated differently in which the government needs to identify the big picture of the problem. In this regard, the role of leadership played by the President is critical to determine what actions can be possibly taken and measure the potential impacts of delaying the actions. As a result, creative and strategic steps are necessary, aligning with the recovery policies. In terms of potential opportunities, promoting a circular economy would accelerate the government’s commitment to low-carbon development. Moreover, optimizing blended finance to mobilize public and philanthropic funds can support green movements, aligning with the proliferation of green financial markets. Thus, the Covid-19 crisis has become a moment to seize the opportunity for redesigning climate policies, including financing mechanisms and improving the governance in climate adaptation and mitigation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

It has been more than 5 years since the Paris Agreement (COP21) entered into force, while the progress made by 184 countries ratifying to limit the increase in global temperature to well below 2 °C above preindustrial levels is still questionable. Watson et al. (2019) find that almost 75% of the 184 climate pledges are partially or even totally insufficient to contribute to reducing emissions by 2030, and some of these pledges could not be achieved. Similarly, it is predicted that some countries will not reach their goals, and some of the world’s largest emission contributors will continue to increase their emissions (Leahy, 2019). However, global renewable energy capacity grew significantly by 50.39% from 2013 to 2018 (IRENA, 2019), and its supplies are estimated to expand by 50% in the next 5 years, driven by a resurgence in solar energy (Ambrose, 2019), showing a strong decarbonization commitment.

Tackling climate change cannot be separated from economic and political issues. This has led to an emergence of global discourses about the appropriate means for a sustainable transformation. In other words, there is a need to design an ideal condition to achieve economic growth, improve human well-being, and reduce environmental risks at the same time. The concept of “green economy” or “green growth,” a vision initiated by (UNEP, 2009), is a much-discussed topic among scholars seeking to accommodate both economic growth and ecological sustainability; the concept, however, receives critics as well (Death, 2015). The green economy seems radical and utopian, legitimating new forms of capitalism,” green capitalism,” and maintaining capitalist hegemony (Brockington, 2012; Tienhaara, 2014; Wanner, 2015). Further, Hickel and Kallis (2019) find no substantial evidence that decoupling from carbon emissions could be achieved, so green growth is likely to be a misguided paradigm.

Aside from criticisms, the green economy is a “popular” vision adopted by many countries as a basis for balancing economic, social well-being, and ecological goals. Along with the implementation, however, the Covid-19 pandemic has hampered the green economy vision. Moreover, natural resources exploitation is arguably needed to recover, leading to a higher probability of environmental degradation.

On the other hand, a question related to environmental improvement has raised whether the Covid-19 pandemic causes emissions reduction. Carbon Brief finds that CO2 emissions decreased by 25% over 4 weeks in China; unfortunately, this reduction was temporary as coal consumption at six major power firms in China started to increase with economic recovery (Myllyvirta, 2020). Similarly, there has been a short-term improvement in air quality, but the gain would not last in the long term (The Economist, 2020).

The economic recovery after Covid-19 could lead to a new economic perspective as this pandemic has changed global discourses on how countries refocus on economic growth and address environmental protection. Stiglitz calls the world for a green economy to help the economy out of its Covid-19 torpor (Environmental Finance, 2020). This signifies the world entering a “new-normal” situation and restarting the economy by emphasizing sustainability. Nevertheless, the Covid-19 pandemic is a disaster, especially for developing economies with limited financial and medical resources (Goldin, 2020; UNDP, 2020). Although they are less forced to fight against climate change but more vulnerable to its impact, the Covid-19 also threatens their plans to take climate actions. This problem brings about how they will keep committing to their climate pledges, while access to finance becomes more challenging (Dagnet et al., 2020) as most resources are reallocated to the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, developing countries seem to have “double burdens” to overcome the pandemic and finance their low-carbon transition process. On the other hand, the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, said, “We cannot allow the heavy and rising debt burden of developing countries to serve as a barrier to their ambition [on the climate]” (Guterres, 2020). Therefore, all countries need to sustain climate actions amid this pandemic.

Against this backdrop, we analyze the fate of climate actions in one of the developing countries, Indonesia, considered one of the world’s largest emitters. Although the Government of Indonesia (GOI) has set the NDC target to reduce 29% of GHG emissions below BAU emissions by 2030 and a conditional target of up to 41% reductions with international supports, Climate Action Tracker (2019) assesses the target as highly insufficient and seems ambitious. Nevertheless, it is achievable, requiring an acceleration in renewable energy development, and its obstacles need to be addressed. Another challenge is that GOI needs to secure at least 23,000 MW to meet the national electricity needs by 2025. To this, Indonesia races against time toward a low carbon transition in the energy supply. There is no question that the Covid-19 pandemic has dragged into recession, resulting in the state budget reallocation to overcome this problem.

Thus, our questions are (i) whether climate actions should stay amidst the Covid-19 pandemic and (ii) how to effectively manage and leverage climate actions with potential and available resources to achieve the NDC target. These questions are critical, mainly for policymakers to make strategic institutional decisions in a turbulent environment. This study is qualitative research, using a crisis management framework to provide insights about governing climate change under the Covid-19 pandemic while seizing the opportunities to achieve the climate target. Data were obtained mainly from government reports and statements, news, and other related documents and literature.

This chapter proceeds as follows. Section 19.2 presents crisis management and governance theory as the basis for our analysis. Section 19.3 demonstrates Indonesia’s commitment to climate change, including progress and further actions. We elaborate on stakeholders’ roles related to climate actions in Sect. 19.4. Section 19.5 discusses sustaining climate actions under the Covid-19 storm. Section 19.6 is the conclusion.

2 Crisis Management Governance

In the era of VUCA, organizations are required to be agile to get through every unfavorable situation. In this regard, organizations should react, control, and fix such a situation immediately to minimize potential losses and become resilient. Also, seizing opportunities is considerable for improvement as the unfavorable situation will transform into opportunities for future capital accumulation (Farazmand, 2014). Moreover, unpredictable events, such as crises, are viewed as external forces; thus, a direct and identifiable response is required (Gilpin & Murphy, 2008). Thus, crisis management is needed to make organizations survive.

Pearson and Mitroff (1993) propose four crisis management variables: types of crises, crisis phases, systems (causes), and stakeholders. In relation to this, Pearson and Clair (1998) identify factors contributing to the degree of organizational success or failure from the crisis, such as executive perceptions about risk, environmental context, adoption of organizational crisis management preparations, triggering events, and cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses. Farazmand (2014) suggests four variables related to crisis management: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. These factors will determine whether the success outcome outweighs the failure outcome. However, Gilpin and Murphy (2008) point out that successful crisis management is not determined by scientific planning and prescriptive decision making; instead, the nature of the organization, the crisis, and the environment are factors influencing the outcomes. Also, aspects, such as structural or organizational features, actor constellations and strategies, administrative characteristics in combination with cultures, are the key to understanding the process and performance of crisis governance (Andrews, 2013; Kuhlmann et al., 2021).

Analyzing crisis using a crisis management perspective has been practiced at any level of organizations. At a country level, crisis management plays a prominent role in determining survival during the crisis. Boin et al. (2005) state that cooperation among countries and strong leadership are critical. In public organizations, leadership, supported by a robust institutional framework, has played a crucial role in crisis management as citizens expect their policymakers to avert the threats or minimize the risks (Boin et al., 2005). This emphasizes the importance of leadership and stakeholder perceptions in the crisis management (Bundy et al., 2017). Besides, Kuhlmann et al. (2021) argue that crises provide an opportunity for political actors to show their leadership and effective governance; thus, they gain support from citizens or even win political competitions.

Crisis management is critical in directing the government to handle the Covid-19 pandemic effectively (Mizrahi et al., 2021). This requires good cooperation among public officials, policymakers, and citizens to reduce risks and minimize costs for society (Mizrahi et al., 2021). In other words, the dialogue between the organization (policymakers) – a country, and its stakeholders – nongovernmental and multilateral agencies is essential during the policy-making process to deal with the crisis (Henderson, 2014; Oyama, 2010). In addition, power relations in governance configurations and regulatory strategies are needed to handle the Covid-19 situation (Lidskog et al., 2020). Hence, crisis management cannot be separated from governance in which power distribution, control, and coordination among entities within the government system are necessary.

Several variables are vital to crisis management governance, such as leadership and stakeholders’ perception in which their interaction and dialogue lead to a solid institution and governance. However, this needs to consider the environmental context to identify and mitigate problems, causes, regulative issues, and impacts. In this case, an organization should be open-minded and risk-taking. As the crisis causes an effect, response analysis and creative and strategic thinking are required to design and implement coping strategies for recovery. Thus, organizations are encouraged to be responsive to any changes and have firm decisions and actions.

3 Indonesia’s Commitment to Climate Change: Progress and Further Actions

Regarding climate actions, two challenging sectors to be addressed are AFOLU and energy. For AFOLU, one of the most significant contributors to emissions is forest fires caused by the massive land conversion. To address such an issue, GOI has implemented five priority policies: (i) combating illegal logging and forest fire, (ii) restructuring of industries engaged in the forestry sector, (iii) forest rehabilitation and conservation, (iv) promoting sustainable forest management, and (v) supporting local communities’ economy (Fig. 19.1). Also, GOI has shown its commitment through REDD+ results-based payments, supported by a number of regulations in managing natural forests.

Climate mitigations per sector. (Source: Indonesia Second Biennial Update Report 2018)

Based on KLHK’s performance report, from 2010 to 2014, GHG emissions reduction is relatively significant, except in 2013 and 2014. However, in 2015, GHG emissions increased considerably, which exceeded the BAU level. GHG emissions dropped in 2017 and 2018 but jumped in 2019 (Fig. 19.2). The main factors contributing to emissions in the forest sector include changes in carbon stocks, peat decomposition, and peat fire. Dwisatrio et al. (2021) find that deforestation and forest degradation remain significant challenges and contribute to GHG emissions, particularly forest land-use change and peat fires (around 48% of the country’s GHG emissions).

GHG emissions reduction in the forest sector. (Source: KLHK, 2020)

In terms of the energy transition, Indonesia has made relatively slow progress in renewable energy capacity compared to the other nine largest GHG emitters (Fig. 19.3). Besides, GOI is undeniably facing a significant challenge to a low-carbon energy system considering a high reliance on fossil fuels and abundant coal resources (Fig. 19.4). In addition, the political economy contributes to the discourse of energy transition in which fossil fuel resources contribute to state revenues.

Progress energy mix. (Source: MEMR, 2020)

Furthermore, from all sectors, GHG emissions declined by 1.866 MtonneCO2e (2.04% out of 16.28% target). However, this achievement was only 14.75% of the target. Figures 19.5 and 19.6 depict the National GHG inventory and its detailed emission reduction by sector in 2019. This performance has put Indonesia in the 24th position in the Climate Change Performance Index 2021 (KLHK, 2020).

Progress of climate actions – GHG emissions reduction. (Source: KLHK, 2020)

Progress of climate actions – GHG emissions reduction in 2019 (tonne CO2). (Source: KLHK, 2020)

Although climate actions show significant achievement, supportive policies with strong political commitment and appropriate institutional arrangements are required, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic. GOI needs to realize that the NDC 2030 target is the near-term climate goal. Thus, immediate, rapid, and intensified climate actions are needed considering the progress made since the Paris Agreement entered into force. GOI’s long-term strategies for low carbon and climate resilience 2050 (LS-LCCR 2050) provide a comprehensive approach to climate governance that can accelerate GHG emissions reduction (GOI, 2021). In this case, cross-cutting issues need integrated actions involving multiple sectors.

For further actions, GOI emphasizes the importance of strategic partnerships to not only support the transition to a low-carbon economy but also recover the economy from the Covid-19 adverse effects. However, it is worth noting that strategic partnerships should provide mutual benefits. The case of Norway, for instance, can be a lesson learned to improve climate governance. As stipulated in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, strategic partnerships play a crucial role in achieving climate objectives through international collaborations (Mraz, 2021).

Last, as in the LS-LCCR 2050, GOI focuses on harmonizing mitigation and adaptation actions. For mitigation, sectors such as agriculture, forestry, energy, waste, and IPPU will be connected to adaptation aspects with several targets: (i) economic resilience, (ii) social resilience and livelihood, and (iii) resilience and landscape. These targets cover priority areas, including food, water, energy, health, ecosystem, and disaster. The detailed actions are provided in NAM-NAP. Since the FOLU and energy sectors are the primary sources of emissions, they have been targeted to achieve climate goals. To this, FOLU will become a net sink, and the energy system will be set to near zero in the long-term actions.

4 Stakeholders’ Roles: Governance as Cross-Sector Collaboration

Undeniably, the Covid-19 pandemic attacking the world was unpredictable. While Indonesia had time on its hand, unfortunately, the spread of Covid-19 could not be anticipated due to the tendency to underestimate and be antiscientific. This denial made the government stutter in responding to Covid-19. As a result, the government was unprepared, leading to poor crisis management.

Although crisis management was not well-implemented at the beginning of the outbreak, the government’s responses to encountering the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic were financially significant, resulting in a higher government budget deficit of around 6.34%. Also, the government has established a Covid-19 Task Force. However, the proposed national economic recovery policies limited addressing the issue of climate actions directly. Instead, the policies mainly focus on health, social protection, SMEs, the private sector, and government-related institutions.

Furthermore, along with implementing economic recovery policies, GOI shows its climate commitment by promoting “build back better,” as echoed worldwide. But unfortunately, such a commitment seems unclear enough, mainly related to governance and stakeholders’ roles. To this, the involvement of stakeholders in the policy-making process is critical to ensure that state and nonstate actors (e.g. businesses, NGOs, CSOs, and community) can take steps proportionately and feel more engaged and responsible for achieving the NDC target. In this regard, their actions should be aligned with the economic recovery process.

A lesson from the Covid-19 pandemic, Ahmad (2020) argues that catastrophic outcomes may occur if there is a lack of coordinated actions among government actors and financing. Admittedly, the Covid-19 pandemic is a multidimensional issue that connects human health and environmental systems, so it is necessary to build a resilient world under shared governance in addressing such problems (Jowell & Barry, 2020). In other words, working together to overcome the Covid-19 pandemic and staying actions toward climate change is needed in helping the government to lessen the burden. Ruiu (2020) suggests the need for multilevel collaboration that aligns collective and individual actions for Covid-19 and climate change. In relation to this, there is no single monocentric global governance arrangement in climate change, in which a single, hierarchical unit structures the activities of all other units (van Asselt & Zelli, 2018). In this regard, a polycentric governance approach (see Jordan et al., 2018a) that emphasizes collaborative partnerships among government, private sectors, NGOs, CSOs, international cooperation agencies, and academics has played a critical role in the national response to climate change.

GOI has released NAM-NAP and several prioritized strategies on climate change management, which set out mandatory to specific line ministries to be responsible in the domain sector and provide a policy mechanism to facilitate coordination among all stakeholders. Each actor can contribute to managing climate change through their interests and roles. For instance, the private sector is a key to scale up investment and encourage innovation in a green project. In addition, a corporate social responsibility program can be used to boost local people’s awareness, drive action, and offer positive environmental effects. Engagement of nonstate parties such as NGOs and CSOs have a pivotal role in facilitating society’s needs and decreasing climate risk vulnerability at the grassroots level. In this case, society needs to know the benefits of taking actions on climate change as they fight for the Covid-19 pandemic (see Howarth et al., 2020). In the global scope, multilateral agencies assist in reaching NDC goals through their best practice programs and financial aid to make contributions effective (see Andonova et al., 2018; Jordan et al., 2018b; Mraz, 2021). For coordination and building synergy among actors, governance has primary authority to enhance engagement in climate resilience. Therefore, partnerships across diverse actors are the key in delivering climate actions in targeted sectors (forestry, agriculture, energy, waste management, and IPPU) (Fig. 19.7).

The implementation of climate action and policies needs intense coordination across stakeholder authorities. Unfortunately, the issue of coordination is one of the main challenges in the planning and execution in Indonesia, the more so if linked to the political structure and decentralized governance system (Bappenas, 2012). On the other hand, climate change management still faces sectoral egoism and uneven distribution of information. For instance, in the REDD++ program, forest management is within the jurisdiction of KLHK, while deforestation cases are often related to other ministries. Such a problem reflects the ineffectiveness of cross-sectoral coordination structures and institutions in coping with deforestation (Indrarto et al., 2012). In other words, GOI’s commitments remain weak as there are a number of contradictory regulations and poor coordination among government agencies (Dwisatrio et al., 2021). In relation to this, a well-governance should be implemented by emphasizing the principles of inclusiveness, transparency, easy access to information and accountability with solid coordination (Bappenas, 2019). Therefore, the need for leadership played by the President is pivotal to direct stakeholders’ roles so that Indonesia can pursue sustainability and economic development simultaneously.

5 Discussion: Sustaining Climate Actions Under the Covid-19 Storms

5.1 Managing Climate Actions: An Evaluation Towards the Paris Target

The Covid-19 pandemic remains a significant challenge, affecting the health system and the economy. Still, climate change requires consistent and strong commitment, considering the near-term target in 2030. GOI has designed a set of strategies to build a strong foundation related to governing climate change actions with a supportive policy framework. As a result, various breakthroughs have been implemented to ensure actions align with the NDC target, such as establishing ICCTF, increasing the budget for climate change goals, and enabling environment and comprehensive fiscal framework (Fig. 19.8).

Breakthroughs done by GOI to address climate change. (Source: Author(s))

Notes: The green projects funded by Green Sukuk are selected from tagged projects that fall into one of the nine Eligible Green Sectors under the framework; The Green Sukuk proceeds are used for both financing and refinancing Eligible Green Projects

GOI has taken progressive steps to reform the budgeting management system and increase investments to support RAN GRK. In 2009, ICCTF was established to catalyze and mobilize funding sources for climate mitigation and adaptation programs. As an innovation fund, ICCTF has been an alternative funding mechanism to blend international and domestic funds to invest in vulnerable sectors and high-risk areas. With a robust approach to multistakeholder’s decision-making, this fund provides opportunities for strengthening collaboration across donors and key stakeholders (Halimanjaya et al., 2014). As a result, ICCTF successfully collected USD 3.621 million, consisting of a state budget (15%) and multilateral donors (e.g., Asian Development Bank and World Bank) (85%) in 2021 (ICCTF, 2021).

Further, ICCTF funded several programs that are part of the COREMAP – CTI World Bank and COREMAP – CTI Asian Development Bank grant projects. The activities include constructing a monitoring tower infrastructure, eco-tourism information center, and compiling “A Blue Finance Policy Note: Financing options for small-medium fisheries enterprise and marine conservation in Indonesia,” part of a collaboration with KKP. In addition, ICCTF has shown that climate change can push Indonesian development practices to adopt new approaches (Halimanjaya et al., 2014). Last, ICCTF has effectively managed and allocated existing funding; it has managed to modestly utilize limited funding available to implement adaptation programs in line with national policy pathways and with the excellent representation of stakeholders (Sheriffdeen et al., 2020).

Another significant progress in strengthening climate budgeting management is CBT to evaluate public expenditure by tracking funds and enhancing effectiveness allocations to reach NDC’s targets since 2016. This scheme integrates ministries, agencies, and local governments’ planning, monitoring, reporting, and evaluation systems. Figure 19.9 shows the process of budget tagging that follows the government’s planning and budgeting cycle. Under this process, ministries and institutions collect work plans containing the program, output, and budgeting related to climate change through planning and budgeting system (ADIK and KRISNA applications). Ministries and institutions can perform self-assessment on mitigation, adaptation, and cobenefit output by referring to the national policies strategies of climate change (RAN GRK, RAN API, NDC). The MoF, Bappenas, and KLHK will review the output to ensure the budget for addressing climate change. This step aims to recognize results that directly and indirectly impact GHG emission reductions. In this regard, GOI can identify potential projects that can be financed by Green Bond/Sukuk issuance and other public funding sources such as balance funds (e.g., DAU, DBH, DAK), village funds, regional incentive funds, and provincial to district or city transfer instrument scheme (Fiscal Policy Agency, 2019).

Budget tagging in the national planning and budgeting cycle. (Source: Fiscal Policy Agency, Ministry of Finance, 2019)

In 2019, BPDLH was formed to increase the private sector’s participation and leverage public and development partners’ funds. BPDLH has a legal mandate but not the right to benefit, and the beneficiaries have equitable ownership, which brings the right to benefits. Nevertheless control can only be conducted by the trustee (IMF, 2001). BPDLH acts as a fund manager with flexibility in allocating funds to beneficiaries. The source of funds managed by BPDLH is from the state budget (reforestation fund), Green Climate Fund, Forest Carbon Partnership, and BioCarbon Fund.

Furthermore, GOI has issued Green Sukuk from 2018 to 2021 as an alternative instrument, reaching USD 3.5 bn of Global Green Sukuk and USD 473.1 mn of Green Sukuk Retail in 2019 until 2020. The proceeds were allocated to renewable energy, sustainable transport, energy efficiency, waste and energy management, and resilience to climate change for highly vulnerable areas and sectors (DRR). As a result, in 2018–2020, the projected emission reduction from the issuance of green Sukuk has reached 10, 3 MtonneCO2. Besides, the GOI has launched another sustainable financing instrument, namely, the SDGs Bond, in 2021.

Although GOI has made significant progress, particularly in financing climate actions, the Covid-19 crisis undeniably negatively affects the state budget. Because climate action cannot be addressed separately, GOI should not halt any effort to achieve its climate pledge; thus, response to both crises should be made simultaneously and embedded with the national economic recovery policies. Wyns and van Daalen (2021) argue that NDCs offer a powerful policy platform to link near-term national strategies and Covid-19 recovery efforts.

Unlike previous crises, GOI needs to identify the big picture of the Covid-19 problem. In this regard, the role of leadership played by the President is critical to determine what actions can be possibly taken in line with economic recovery policies and measure the potential impacts if GOI delays the efforts. To this, the President should keep directing KLHK to take the lead and coordinate with other ministries, particularly MoF, regarding financial resources and design climate change policies.

In response, the MoF (2020) proposes three strategies to address the NDC target, such as (i) making adjustments to action plans by considering the national economic recovery policies, (ii) prioritizing action plans that can recover the economy simultaneously, and (iii) developing innovative financing schemes and policies to encourage nongovernment parties’ participation.

Strategies designed by GOI might help climate actions work during and after the pandemic. However, it is critical to consider the timeframe, requirements, and performance indicators that KLHK must formulate so the targets are relatively more measurable (Firdaus, 2020). Precise stimulus package measures help GOI minimize climate risks caused by delayed decarbonization. In the Covid-19 pandemic, the short-term objective of the economic recovery policies is to bring a significant economic impact and transform the economic structure that can ensure GOI meets its climate goals in the long term (see Fig. 19.10).

Since no one knows when the Covid-19 crisis will end, leading to uncertainty and disruptions in emission reduction plans, it is necessary to keep committing to the climate pledge. Undoubtedly, delaying actions may save money in the short run, but climate actions would be more costly in the long run. In terms of emissions, the accumulated CO2 would surpass the carbon budget. Although the world is calling for a green economy to revitalize the existing system, considering the domestic situation with limited resources, GOI might face difficulties realizing its commitment to climate change. Thus, external supports are needed to ensure that climate actions are sustainable.

Climate change undeniably threatens the livelihoods of vulnerable communities, so it is critical to consider the microlevel in which the Covid-19 crisis may jeopardize community resilience. Financial and nonfinancial supports to that effect should be provided to guarantee vulnerable communities in meeting their needs. The Covid-19 pandemic that has hit global markets and impeded trade lines affects the domestic economy so that the demand for goods produced by communities drops, and subsequently, they potentially lose their income. Therefore, managing vulnerable populations associated with climate change in the Covid-19 crisis should be included in the policies to maintain their contribution to climate adaptation and mitigation.

The national economic recovery policies support economic activities and promote economic stability. Adjusting climate action plans can be a coping strategy to ensure that GOI commits to the Paris Agreement. Consequently, Covid-19 fiscal recovery packages consider both economic multiplier and climate impact to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy. In other words, the Covid-19 pandemic is the moment for GOI to rebuild the economy with a new paradigm, so-called build back better, by putting forward inclusivity and sustainability. Besides, restoring public confidence is the key to sustaining climate actions where stakeholders can participate in emission reduction pathways. Nonetheless, clearly defined policies and regulations are vital as a guideline for aligning economic recovery and climate goals.

Finally, Covid-19 indicates that the world is fragile, and crisis response strategies are needed to address this fragility. GOI can take lessons from the Covid-19 crisis to reform its governance institution and reformulate strategies concerning crisis management. Addressing climate change is not similar to tackling the Covid-19 pandemic as they have different challenges. However, both climate change and Covid-19 are part of global issues requiring stakeholders to work together to find solutions. Besides, in the context of crisis management, the Covid-19 crisis has signaled GOI to develop creative and strategic thinking and evaluate aspects, such as transparency, leadership, coordination, and communication, to be more adaptive and vigilant for the next crises. Thus, during the Covid-19 crisis, climate actions should remain in place and be prioritized so that GOI can show its commitment to the Paris Agreement.

5.2 The Covid-19 Crisis: Any Opportunities and Potential Challenges?

There is an opportunity in every crisis; thus, GOI can seize it to address climate change. The Covid-19 pandemic indirectly sends a message to show the weaknesses of the existing health system, causing economic shocks and ecological degradation (see Mansuy, 2020). Subsequently, redesigning the system to overcome those weaknesses to create a better world is necessary. Because of this, a “green recovery” has been intensively echoed in which Covid-19 stimulus packages should boost economic growth and stop climate change. CarbonBrief (2020) identifies countries (e.g., European Union, South Korea, India, and China) committing to cut their emissions after coronavirus through “green recovery” plans that focus on several sectors, such as agriculture, buildings, energy, employment (green jobs), industry, nature, and transport. Unlike standard recovery stimulus packages that may also include fossil companies to be bailed out, green recovery plans more focus on sustainable purposes. Hepburn et al. (2020) classify five policies that positively impact the economy and climate: clean physical infrastructure, building efficiency improvements, investment in education and training, natural capital investment, and clean R&D. However, these policies require support from both humans and institutions.

GOI’s commitment toward the LCDI can be realized by adopting the principles of the circular economy that emphasize efficiency, zero waste, and zero emissions. In conjunction with the circular economy, the concept of doughnut economics becomes relevant and should be embraced for future development by considering both planetary and social boundaries (Raworth, 2017). However, implementing the green economy amid the pandemic crisis might be more challenging for Indonesia with limited financial resources. In other words, economic growth is thus far likely regarded as critical to addressing other important issues outside the ecology. Therefore, decoupling of economic growth and carbon emissions remains unsolved as economic recovery post-Covid-19 inevitably requires energy and raw materials consumption that drive an increase in CO2 emissions (Myllyvirta, 2020).

Regardless of the problem, GOI can gradually initiate the transformation and continue the existing and planned climate-related projects in this unexpected situation. These actions should be done as soon as possible to ensure a smooth transition to a sustainable economy. Based on the assessment of fiscal recovery policies in response to the GFC, green stimulus packages have more benefits than traditional fiscal stimulus in which, in the short term, more jobs are created by renewable energy developments (Hepburn et al., 2020). They also claim that ensuring people have income during the economic slowdown is critical to boosting spending and increasing short-term GDP multipliers. When renewables are well-established, requiring less labor but supported by technologies, the costs related to energy production decline in the long term (Blyth et al., 2014; Handayani et al., 2019; IRENA, 2017; Zhongying & Sandholt, 2019). Consequently, GOI should realize that mainstreaming climate actions in stimulus packages for recovery from the Covid-19 crisis becomes a solution to keep on track in achieving the transition to a low carbon economy.

However, during the Covid-19 pandemic, GOI released Law No. 3/2020, the amendment of Law No. 4/2009 concerning Mineral and Coal Mining. This law has been synchronized with the Job Creation Bill (UU Cipta Kerja), resulting in 15 points added as an improvement. This new law is believed to address the problems in the mining sector and provide more benefits to society, the fact that this law has raised controversy. Law No. 3/2020 has been sidelining the environment where GOI allows the expansion of mining territory to increase reserves. Whereas the world is planning a coal phase-out to reach a 1.5 economy, GOI intends to grow coal reserves. High coal reserves undeniably lead to assets stranding, so the value of reserves becomes worthless in the future due to decarbonization. Thus, the commitment to the Paris Agreement in achieving the NDC target is questionable because of the dilemma between environmental protection and economic growth.

Law No. 3/2020, on the other hand, encourages the development of downstream industries to increase the added value of mineral and coal mining. This objective should become an opportunity to revitalize the governance in coal mining through implementing a sustainable approach. DME has become an option to supply clean energy for domestic purposes that can reduce the reliance on importing LPG; it is, however, highly capital intensive and risky. Therefore, to ensure an improvement in the governance in coal mining, GOI needs to strictly regulate coal mining players to protect the environment and help reduce emissions aligning with the pursuit of economic recovery.

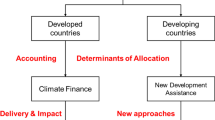

Another opportunity is that GOI can take advantage of the emergence of blended finance as an alternative option to mobilize public and philanthropic funds for achieving climate targets and SDGs during and post Covid-19 pandemic (see Fig. 19.11). However, since capital has never been cheaper, mobilizing public funds requires transparency and detailed information regarding the project’s risk and return. Investors need attractive returns compared to other investment options. Besides, investors should be well informed about the climate actions roadmap to know their investment prospects. Also, a diversified climate project portfolio offered will boost investors’ interest.

Green capital markets are proliferating worldwide in response to support green movements in addressing climate change. The most significant development climate finance instrument recently is green bonds. The World Bank Group has supported emerging markets by cooperating with HSBC and IFC, pioneering REGIO Fund as the first global green bond fund (Klein & de Bolle, 2020). This fund aims to help businesses in emerging countries mitigate climate risks by facilitating public and private capital to transition to cleaner and more efficient energy.

Additionally, although green bonds were not immune to the Covid-19 crisis in a few months (Harrison, 2020; Yu, 2020), leading to the slowdown in bond issuance activity due to lack of green assets, the economic recovery policies materialized to help the markets to revive (Harrison, 2020). This situation provides an opportunity for the issuers, not only sovereigns but also businesses, to fund their climate-friendly projects in the future, aligning with the national economic recovery policies that are expected to stabilize the economy. In other words, GOI can encourage the private sector to participate in green bond markets as, hitherto not many Indonesian companies issue green bonds.

As the future economic situation remains uncertain, financial institutions and businesses may focus on saving their business and minimizing the long-term disruptions. Besides, undeniably the green capital markets are exposed to the Covid-19 crisis, so capital market players expect robust economic recovery policies to restore their confidence in developing the markets. Moreover, unlike green bonds, social bonds have been more attractive during the Covid-19 crisis (Yu, 2020), and they potentially are growing to support the government in providing comprehensive recovery packages (BNP Paribas, 2020). For optimal outcomes, GOI could simultaneously combine these instruments to address the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change, but this option requires supportive policies.

Nevertheless, optimizing existing financing sources, which are not debt instruments to support clean energy projects and scale up to other climate actions, should be the top priority amid limited financial resources due to the budget reallocation for the Covid-19 crisis. This consideration is pivotal to reducing the financial burden. However, GOI needs to set measures so that the progress made can efficiently be assessed. Governance mechanisms are also crucial to ensure that funds can be utilized effectively and donors and investors meet their expectations.

Furthermore, introducing other climate finance instruments, such as carbon pricing, helps GOI to obtain a new funding source to tackle climate change and encourage nonstate actors to participate in emissions reduction. GOI has taken a significant step in carbon pricing policies, including carbon trading, RBP, carbon tax, and emission trading scheme. This action provides a long-term solution for GOI to meet its climate pledge as the Covid-19 crisis has drastically changed the economic and financial landscape. However, it is necessary to coordinate with nonstate actors, especially businesses, as they are the main stakeholder if carbon pricing is implemented. The implementation of carbon pricing should not discourage the business sector from taking action on climate change.

The role of NGOs, CSOs, and communities cannot also be neglected to channel climate funds. For instance, carbon offset instruments can be directed to communities living in the forest areas through cooperation schemes and community empowerment. This mechanism can provide sustainable livelihoods for forest communities as they are most vulnerable to climate change. To ensure such a mechanism, NGOs and CSOs can advocate communities in training and channelling to markets. Communities living in the forest areas mostly lack infrastructure, resources, and markets, so the role of NGOs and CSOs is significant.

Finally, the Covid-19 crisis opens a window of opportunity for politicians and leaders to change the rules of the game and transform institutional settings (Kuhlmann et al., 2021). Collaborative stakeholders are needed to actualize effective instruments and encourage inclusive development. The right political leadership can lead to ambitious outcomes that will have a significant impact on addressing climate change (Stojanovska-stefanova & Vckova, 2016). Therefore, it is expected that the Covid-19 crisis may accelerate countries to build back and be better and more resilient in sustainable pathways.

6 Conclusion

The Covid-19 crisis has disrupted climate action plans, and the impact is beyond health issues, causing a domino effect. Although the Covid-19 crisis has become the priority and current threats to be solved immediately, climate change cannot be ignored as it is a future issue that needs a quick and effective response. Unlike the Covid-19 pandemic with direct impacts, climate change might be considered long term and has indirect impacts, but the sense of urgency should be the same. In this regard, should climate actions stay amidst the Covid-19 pandemic? The answer is “Yes.” People may have adapted their lives to a sudden and significant change due to the Covid-19 pandemic; thus, climate actions should be more welcome. Besides, from the GOI’s side, climate actions can go parallelly with the national economic recovery policies by emphasizing the importance of climate change actions to the society so that GOI can achieve the target during the specified time.

Aligning with efforts to overcome Covid-19 that require citizens’ willingness to cooperate with the government, climate actions should be responded to similarly. It is admitted that Indonesia was stuttered to overcome the Covid-19 pandemic in the beginning, resulting in poor crisis management, but then gradually responded to the crisis with better measures. In this case, policymakers holding the authority are expected to become more responsible as they are facing two issues simultaneously. Also, strong coordination between the central government and local government is critical. In other words, multilevel collaborations are needed to minimize costs and ensure that both Covid-19 and climate change can be handled appropriately in which the role of leadership played by the President and supported by KLHK and MoF is crucial to orchestrating policies.

As in the context of crisis management, the Covid-19 pandemic is the moment for the government to seize the opportunity to redesign its climate policies, including financing mechanisms and improving climate mitigation and adaptation governance. From the Covid-19 crisis, GOI can learn the weaknesses of the current system that need to be addressed and start to rebuild with a new perspective. In other words, a new paradigm, “circular economy,” which emphasizes both planetary and societal boundaries, is what the world needs for the future and GOI should move toward that paradigm. Thus, it is expected that Indonesia will be more resilient in response to climate change threats in the future.

References

Ahmad, E. (2020). Multilevel responses to risks, shocks and pandemics: Lessons from the evolving Chinese governance model. Journal of Chinese Governance, 0(0), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2020.1813395.

Ambrose, J. (2019). Renewable energy to expand by 50% in next five years. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/21/renewable-energy-to-expand-by-50-in-next-five-years-report

Andonova, L., Castro, P., & Chelminski, K. (2018). Transferring technologies: The polycentric governance of clean energy technology. In A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. van Asselt, & J. Forster (Eds.), Governing climate change: Policentricity in action? (pp. 266–284). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108284646.01

Andrews, M. (2013). The limits of institutional reform in development: Changing rules for realistic solutions. Cambridge University Press.

Blyth, W., Gross, R., Speirs, J., Sorrell, S., Nicholls, J., Dorgan, A., & Hughes, N. (2014). Low carbon jobs: The evidence for net job creation from policy support for energy efficiency and renewable energy. UK Energy Research Centre. https://d2e1qxpsswcpgz.cloudfront.net/uploads/2020/03/low-carbon-jobs.pdf

BNP Paribas. (2020, July 27). Capital markets and Covid-19: have social bonds come of age? https://cib.bnpparibas.com/sustain/capital-markets-and-covid-19-have-social-bonds-come-of-age-_a-3-3503.html

Boin, A., Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2005). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge University Press.

Brockington, D. (2012). A radically conservative vision? The challenge of UNEP’s towards a green economy. Development and Change, 43(1), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01750.x

Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M. D., Short, C. E., & Coombs, W. T. (2017). Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation, and research development (Vol. 43).

CarbonBrief. (2020). Coronavirus: Tracking how the world’s ‘green recovery’ plans aim to cut emissions. Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/coronavirus-tracking-how-the-worlds-green-recovery-plans-aim-to-cut-emissions

Climate Action Tracker. (2019, May 3). Climate Action Tracker: Indonesia. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/indonesia/

Dagnet, Y., Cogswell, N., & Mendoza, J. M. (2020). 4 ways to strengthen climate action in the wake of COVID-19. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/05/coronavirus-strengthen-climate-action

Death, C. (2015). Four discourses of the green economy in the global South. Third World Quarterly, 36(12), 2207–2224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1068110

Dwisatrio, B., Said, Z., Permatasari, A., Maharani, C., Moeliono, M., Wijaya, A., Lestari, A. A., Yuwono, J., & Thuy, P. T. (2021). The context of REDD+ in Indonesia: Drivers, agents and institutions (2nd edn.) (No. 216; CIFOR occasional paper). https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/OccPapers/OP-216.pdf

Environmental Finance. (2020, May 5). Nobel prize-winning economist calls for Green Deal after Coronavirus. Environmental Finance. https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/news/nobel-prize-winning-economist-calls-for-green-deal-after-coronavirus.html.

Farazmand, A. (2014). Crisis and emergency management: Theory and practice. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Crisis and emergency management: Theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 1–9). CRC Press.

Firdaus, N. (2020). Stimulus Covid-19, Pencapaian Target Iklim, dan Tantangan Sektor Bisnis. https://money.kompas.com/read/2020/07/14/060700526/stimulus-covid-19-pencapaian-target-iklim-dan-tantangan-sektor-bisnis

Fiscal Policy Agency. (2019). Pendanaan Publik Untuk Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Indonesia Tahun 2016–2018.

Gilpin, D. R., & Murphy, P. J. (2008). Crisis management in a complex world. Oxford University Press.

Goldin, I. (2020, April 21). Coronavirus is the biggest disaster for developing nations in our lifetime. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/21/coronavirus-disaster-developing-nations-global-marshall-plan

Government of the Republic of Indonesia. (2018). Indonesia second Biennial update report. Directorate General of Climate Change, Ministry of Environment and Forestry. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Indonesia-2nd_BUR.pdf

Government of the Republic of Indonesia. (2021). Indonesia long-term strategy for low carbon and climate resilience (LTS LCCR) 2050. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Indonesia_LTS-LCCR_2021.pdf

Guterres, A. (2020). Remarks to Petersberg climate dialogue. United Nations Secretary-General. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2020-04-28/remarks-petersberg-climate-dialogue.

Halimanjaya, A., Nakhooda, S., & Barnard, S. (2014). The effectiveness of climate finance: A review of the Indonesia climate change trust fund (Issue March).

Handayani, K., Krozer, Y., & Filatova, T. (2019). From fossil fuels to renewables: An analysis of long-term scenarios considering technological learning | Elsevier enhanced reader. Energy Policy, 127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.11.045

Harrison, C. (2020). EUR green bonds pricing dynamics H1 2020. Webinar: Green Bond Pricing in Primary Market. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gu3AamUsGYw&%3Bt=3s.

Henderson, L. J. (2014). Managing human and natural disasters in developing nations: Emergency management and the public bureaucracy. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Crisis and emergency management: Theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 317–330). CRC Press.

Hepburn, C., O’Callaghan, B., Stern, N., Stiglizt, J., & Zenghelis, D. (2020). Will COVID-19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change? Oxford Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. https://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/publications/wpapers/workingpaper20-02.pdf

Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2019). Is green growth possible? New Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

Howarth, C., Bryant, P., Corner, A., Fankhauser, S., Gouldson, A., Whitmarsh, L., & Willis, R. (2020). Building a social mandate for climate action: Lessons from COVID-19. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), 1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00446-9

Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund [ICCTF]. (2021). Laporan Triwulan 1: Januari - Februari - Maret 2021.

Indrarto, G. B., Murharjanti, P., Khatarina, J., Pulungan, I., Ivalerina, F., Rahman, J., Prana, M. N., Resosudarmo, I. A. P., & Muharrom, E. (2012). The context of REDD+ in Indonesia: Drivers, agents, and institutions (No. 92; CIFOR occasional paper). https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/WPapers/WP92Resosudarmo.pdf

International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA]. (2017). Renewable power generation costs in 2017. International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA]. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Jan/IRENA_2017_Power_Costs_2018.pdf

International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA]. (2019). Renewable Capacity Statistics 2019. International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA]. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Mar/IRENA_RE_Capacity_Statistics_2019.pdf

International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA]. (2020). Renewable capacity statistics 2020. https://irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2020/Mar/IRENA_RE_Capacity_Statistics_2020.pdf

Jordan, A., Huitema, D., Schoenefeld, J., van Asselt, H., & Forster, J. (2018a). Governing climate change Polycentrically. In A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. van Asselt, & J. Forster (Eds.), Governing climate change: Polycentricity in action? (pp. 3–26). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108284646.002

Jordan, A., Huitema, D., van Asselt, H., & Forster, J. (2018b). Governing climate change: The promise and limits of polycentric governance. In A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. van Asselt, & J. Forster (Eds.), Governing climate change: Policentricity in action? (pp. 359–383). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108284646.021

Jowell, A., & Barry, M. (2020). COVID-19: A matter of planetary, not only national health. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(1), 31–32. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0419

Klein, A., & de Bolle, P. (2020). Green bonds become real in emerging markets. https://blogs.worldbank.org/climatechange/green-bonds-become-real-emerging-markets.

Kuhlmann, S., Bouckaert, G., Galli, D., Reiter, R., & Van Hecke, S. (2021). Opportunity management of the COVID-19 pandemic: Testing the crisis from a global perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852321992102

Leahy, S. (2019). Most countries aren’t hitting Paris climate goals, and everyone will pay the price. National Geographic https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/11/nations-miss-paris-targets-climate-driven-weather-events-cost-billions/

Lidskog, R., Elander, I., & Standring, A. (2020). COVID-19, the climate, and transformative change: Comparing the social anatomies of crises and their regulatory responses. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(16), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12166337

Mansuy, N. (2020). Stimulating post-COVID-19 green recovery by investing in ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology, 28(6), 1343–1347. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13296

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Indonesia [MEMR]. (2020). Handbook of Energy & Economic Statistics of Indonesia.

Ministry of Environment and Forestry [KLHK]. (2020). Laporan Kinerja Kementerian Lingkugan Hidup dan Kehutanan.

Ministry of Finance Republic of Indonesia [MoF]. (2020). Dukungan Fiskal di tengah Pandemi COVID-19 dan Pencapaian Target NDC Pasca Pandemi: Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional (PEN) dan Pembiayaan Perubahan Iklim Pasca Pandemi.

Ministry of National Development Planning [Bappenas]. (2012). National Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation.

Ministry of National Development Planning [Bappenas]. (2019). National Adaptation Plan Executive Summary.

Mizrahi, S., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Cohen, N. (2021). How well do they manage a crisis? The Government’s effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13370

Mraz, M. (2021). Identifying potential policy approaches under article 6 of the Paris agreement: Initial lessons learned. https://gggi.org/site/assets/uploads/2021/01/Policy-Approaches-under-PA-Article-6210121.pdf.

Myllyvirta, L. (2020). Analysis: Coronavirus temporarily reduced China’s CO2 emissions by a quarter. Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-has-temporarily-reduced-chinas-co2-emissions-by-a-quarter.

Oyama, T. (2010). Post-crises risk management: Bracing for the next perfect storm. Wiley.

Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. The Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/259099

Pearson, C. M., & Mitroff, I. I. (1993). From crisis prone to crisis prepared: A framework for crisis management. Academy of Management Perspectives, 7(1), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1993.9409142058

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Random House Business Books.

Ruiu, M. L. (2020). Mismanagement of Covid-19: Lessons learned from Italy. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7–8), 1007–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758755

Sheriffdeen, M., Nurrochmat, D. R., Perdinan, & Di Gregorio, M. (2020). Indicators to evaluate the institutional effectiveness of national climate financing mechanisms. Forest and Society, 4(2), 358–378. https://doi.org/10.24259/fs.v4i2.10309

Stojanovska-stefanova, A., & Vckova, N. (2016). International Strategy For Climate Change And The Countries Commitment For Developing Policies. In: International Scientific Conference: Crisis Management: Challenges and Perspective, 18 Nov 2015, Skopje, Macedonia.

The Economist. (2020). Covid-19 and climate change: Clear thinking required. The Economist, 76–78.

Tienhaara, K. (2014). Varieties of green capitalism: Economy and environment in the wake of the global financial crisis. Environmental Politics, 23(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.821828

United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]. (2020, May 10). COVID-19: Looming crisis in developing countries threatens to devastate economies and ramp up inequality. United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/news-centre/news/2020/COVID19_Crisis_in_developing_countries_threatens_devastate_economies.html

United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]. (2009). Global green new deal policy brief. United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/7903/A_Global_Green_New_Deal_Policy_Brief.pdf?sequence=3&%3BisAllowed=

van Asselt, H., & Zelli, F. (2018). International governance. In A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. van Asselt, & J. Forster (Eds.), Governing climate change: Polycentricity in action? (pp. 29–46). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108284646.003

Wanner, T. (2015). The new ‘passive revolution’ of the green economy and growth discourse: Maintaining the ‘sustainable development’ of neoliberal capitalism. New Political Economy, 20(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.866081

Watson, S. R., McCarthy, J. J., Canziani, P., Nakicenovic, N., & Hisas, L. (2019). The truth behind the climate pledges.

Wyns, A., & van Daalen, K. R. (2021). From pandemic to Paris: The inclusion of COVID-19 response in national climate commitments. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(5), e256–e258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00111-X

Yu, D. (2020). Green bonds not immune to Covid-19 impact. The Asset. https://www.theasset.com/article-esg/40386/green-bonds-not-immune-to-covid-19-impact

Zhongying, W., & Sandholt, K. (2019). Thoughts on China’s energy transition outlook. Energy Transitions, 3, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41825-019-00014-w

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Firdaus, N., Rahmayanti, A.Z. (2023). Should Climate Actions Stay Amidst the Covid-19 Pandemic? A Crisis Management Governance Perspective. In: Triyanti, A., Indrawan, M., Nurhidayah, L., Marfai, M.A. (eds) Environmental Governance in Indonesia. Environment & Policy, vol 61. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15904-6_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15904-6_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15903-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15904-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)