Abstract

The Ciliwung River in Java, Indonesia, is known to cause frequent flooding in the downstream capital city of Jakarta. From source to mouth the river flows through several administrative units. Indonesia’s decentralised governance structure means that each unit has the authority to develop its own plans and to address its own objectives. Not only that, but flood management spans many sectors, and these sectors need to work together throughout the decentralised governance system. This can pose a significant challenge to achieving integrated river management to mitigate flooding, where plans need to be carefully coordinated and high levels of collaboration are required. This chapter examines the current governance arrangements in the Ciliwung River Basin, to understand what challenges may be preventing successful coordination of flood management. The findings of the study are based on a systematic review of the literature conducted within the frame of the NERC and RISTEK-BRIN funded project: Mitigating hydrometeorological hazard impacts through improved transboundary river management in the Ciliwung River Basin. The findings suggest several issues that restrict the effectiveness of coordination for flood mitigation in the Ciliwung Basin. Imprecisely defined roles and responsibilities, issues including lack of capacity at the local level, insufficient coordination between local administrations, and limitations to the function of coordination platforms are some of the challenges identified. The findings highlight that coordination challenges do not only exist at basin scale, but that coordination issues beyond the basin can also have an impact. Overall, the chapter presents insights into the coordination challenges facing flood governance in urban transboundary basins. It also provides insights for practitioners on what aspects of river governance may need to be improved to support flood risk reduction, as well as potential topics for future research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Transboundary river basins, those that cross political borders between countries or administrative jurisdictions, present a particularly complex governance challenge. Managing environmental problems within transboundary basins requires actors on either side of the border (or across multiple borders) to work together. This is due to the interconnectedness of a river basin system, and the fact that actions in one part of the basin are likely to have consequences elsewhere. It is therefore necessary to develop a governance arrangement that allows the relevant actors to coordinate (Bakker, 2009).

As Evans (2012) states in their book on environmental governance, “Governance is about asking what sort of world we want to inhabit, and how we can coordinate getting there” (p. 14). This chapter focuses on coordination as a key governance challenge that impacts society’s ability to manage environmental concerns. To do this, the case of the Ciliwung River Basin, Java, Indonesia is examined. The Ciliwung is a transboundary river basin that crosses into Indonesia’s capital city of Jakarta, and is known to cause acute flooding in the city. A lack of coordination between stakeholders has been noted to be a key issue facing progress towards flood resilience in Jakarta (Dwirahmadi et al., 2019).

Coordination is a term used alongside words such as cooperation and collaboration in the transboundary governance and river governance literature to denote some form of working together. For example, the dictionary definition of coordination is “the act of making all the people involved in a plan or activity work together in an organised way” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2022). Some researchers have distinguished different ways of working together, for example, Watson (2004) distinguishes between coordination and collaboration. They describe coordination as more of a ‘rule-based’ arrangement where government actors align their separate approaches to management. Collaboration on the other hand is seen as a more developed form of governance where actors work more closely together, pooling their expertise and resources to tackle a common problem. It is also often associated with the inclusion of non-government actors (Emerson et al., 2011; Margerum & Robinson, 2015). It has been suggested that collaboration may be better for tackling the complexity of river basin problems, and overcoming state capacity issues (Watson, 2004). Nevertheless, coordination is still required, and it remains a key challenge in the Ciliwung Basin. This chapter focuses on coordination, particularly the coordination of government actors, but also looks at the coordination mechanisms in place which include a wider array of stakeholders, with acknowledgement that this may only be one part of ‘working together’.

This chapter presents the potential challenges facing the coordination of government actors in the Ciliwung River Basin, based on a literature review, and considers whether more developed collaboration may be possible within the basin. The chapter first sets out the context for the case of the Ciliwung River. The reasons why coordination is needed in transboundary basins are then presented. The methodology of the review is then given, followed by the findings on the challenges facing coordination in the Ciliwung. Lastly, the conclusions are given with suggested recommendations for improving coordination in the basin, and implications for environmental governance more widely.

1.1 The Ciliwung River Basin

The Ciliwung River Basin is a transboundary basin in Indonesia that crosses two provincial and five municipal borders. From the river’s source in West Java, near Tugu Puncak, the river passes through the cities of Bogor and Depok before arriving into the downstream capital city of Jakarta. A primary environmental concern within the basin is the frequent and severe flooding in the capital city (Kefi et al., 2020). Jakarta has experienced frequent flooding throughout the city’s history, but recent floods, combined with the threat of climate change, have raised concerns that the problem is becoming worse, and will only continue to worsen in the future. For example, severe floods have been experienced in 2007, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2020. The recent floods in January 2020 were one of the most hazardous recorded, with 67 fatalities and the displacement of 28,000 people to emergency shelters (reports as of tenth January 2020) (ACAPS, 2020). The river itself has undergone a significant amount of structural management, with sections of flood barriers and several flood gates. However, such measures do not protect all areas and have limited sustainability. There is an urgent need to address the flood problem in the Ciliwung Basin in a more integrated manner (Asdak et al., 2018).

1.2 Why Is Coordination Important?

There are several reasons why coordination is a particularly salient issue for flood management in transboundary basins. Firstly, flooding is rarely caused by a single driver, but is often a result of a complex web of causes. This is no more true than in the heavily urbanised, and naturally flood prone, Ciliwung River Basin. Here, there are several physical aspects that contribute to increased flood risk.

Firstly, heavy precipitation events are common. The region has a tropical monsoon climate that brings heavy precipitation during the peak wet season (December–February) (Siswanto et al., 2015), but local convection also brings intense downpours throughout the year (Tjasyono et al., 2008).

In addition, land subsidence, owing to both natural and human processes, has resulted in large parts of Northern Jakarta lying below sea level. Rates of subsidence are estimated to be between one and 15 centimetres per year (dependent on location, and may be higher in places) (Abidin et al., 2011), with recent calculations suggesting accumulated subsidence to be approximately five metres (Cao et al., 2021) The subsidence impairs the effectiveness of drainage systems, and prevents water from the rivers discharging effectively into the sea, resulting in increased flood risk (Abidin et al., 2011). Estimates suggest that continuing subsidence will increase the flood inundation volume in the city 9.1% by 2050 compared to 2013 if unaddressed (Moe et al., 2017).

There are also other human drivers compounding the problem. In the downstream area of Jakarta there has been rapid economic and population growth that has resulted in rapid urbanisation of the city. Over time the city has agglomerated with neighbouring urban areas in the midstream. These high levels of urbanisation have increased the quantity of impermeable surface and led to reduced infiltration and run-off (Remondi et al., 2016). Furthermore, in the upstream part of the catchment, there has been significant deforestation (Asdak et al., 2018). Studies have indicated intensification of basin response and increases in peak flow and sediment load in the Ciliwung as a consequence of land clearance (Remondi et al., 2016). Continued land use change is projected to increase flood inundation volume significantly if overlooked (Moe et al., 2017). Furthermore, urban development and the increased cost of living in Jakarta have pushed the urban poor into informal settlements on the banks of rivers. These settlements are highly exposed and vulnerable to flooding (Hellman, 2015; Texier, 2008). As such, the socio-economic conditions in the city further contribute to the flood risk.

Overall, this interconnecting web of flood drivers means that there will not be a single organisation, or government department that will be able to take care of the flood problem alone. There is a need for different organisations (governmental and non-governmental) to work together, and to coordinate across the traditional arrangement of government sectors in order to pool resources and expertise.

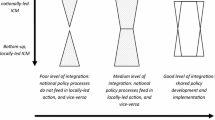

The second reason coordination is key is that transboundary basins cross borders. Integrated River Basin Management (IRBM) is the concept of managing rivers in an integrated manner from upstream to downstream. The principles of IRBM suggest that river basins should be managed at the basin level (Wiering et al., 2010). This is to account for the fact that processes within the hydrologic boundary are connected. Considering the river basin as a whole requires the different jurisdictions through which the river crosses to coordinate to ensure compatibility of plans and balancing of interests, as well as data and information for things like flood early warning (Skoulikaris & Zafirakou, 2019). In Indonesia, there are 34 separate provinces which are sub-divided into rural regencies (kabupaten), urban cities (kota), then into districts (kecamatan) and villages. In the case of the Ciliwung, the borders being crossed are the political borders between administrative areas. The Ciliwung crosses the provinces of West Java and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (DKI Jakarta) as well as the municipalities of Bogor City, Bogor Regency, Depok and Jakarta. To successfully manage the Ciliwung, it is therefore necessary for local governments and organisations to coordinate across the provincial and municipal borders.

Lastly, coordination is of particular importance in multi-level governance systems. Within a country, multi-level systems consist of governments at national through to local level, and the different levels may be responsible to varying degrees. Responsibilities for aspects of flood management, for example, are often distributed across governance levels. To ensure that plans for flooding are implemented successfully, coordination is required between the vertical levels of government so that approaches are matched across scales (Dieperink et al., 2018). In Indonesia’s multi-level governance system, the levels are national, provincial, regency/city, district and village. Therefore, responsibilities for flood management are divided, and vertical coordination is required to translate policy and plans into implementation at the local level.

This chapter examines the potential barriers to coordination that may be impacting on the responsible actors’ ability to manage flooding in the Ciliwung River Basin.

2 Methodology

The findings are based on a systematic literature review. The review was conducted as part of the project Mitigating hydrometeorological hazard impacts through transboundary river management in the Ciliwung River BasinFootnote 1. The aim of the project is to identify the flood-related governance challenges, and to formulate recommendations for how governance arrangements may be improved to support the management of flooding in the Ciliwung.

The literature review was conducted following the project’s conceptual framework (Clegg et al., 2021). The framework partly applied that of Savenije and van der Zaag (2000) for international water sharing, and adapted it to the topic of flooding. The framework was used as a basis to identify governance challenges.

Literature was chosen based on its relevance to flood, water and river management, as well as disaster management literature which may provide useful insights for flooding. Disaster management and water management were included because of the focus of Indonesia’s national frameworks on these areas. Both academic and grey literature sources were reviewed. Sources were identified through searches using Google Scholar and the University of Huddersfield’s online library portal. Key word searches included ‘flood management’, ‘disaster management’, ‘river management/governance’ and ‘water management’ in combination with ‘Ciliwung’, ‘Jakarta’ and ‘Indonesia’. Thus, the literature must relate to either the Ciliwung Basin, Jakarta area or Indonesia more broadly. The initial review identified 76 relevant documents of which 28 were found to have relevance to coordination and are presented in the findings. Some additional literature is included for background to each problem.

3 Findings

3.1 Coordinating Sectors

The issue of flooding is not only relevant to a single government ministry or agency, but cuts across the interests of various. This might include agriculture, spatial planning and land use, climate change, and the environment, among others (Akhmouch & Calavreul, 2019). This is due to flooding being driven by, and affecting, many different aspects of society and the environment. While these government departments may have their own priorities and work plans, there is a need for these to be compatible to support an integrated approach to flood management.

In Indonesia, responsibilities for the management of flooding are distributed between government ministries/agencies, with the primary actors being the Ministry of Forestry, the Ministry of Public Works and the Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) (Ariyanti et al., 2020; Djalante et al., 2013). However, these government departments do not always coordinate effectively. For example, it is noted that in both water management and disaster management, the government departments involved tend to follow their own agendas in a fragmented manner, rather than working together (Mulyana & Prasojo, 2020; Srikadini et al., 2018). Limited coordination has been identified between specific ministries and agencies, such as between BNPB and the Ministry of Forestry by Mardiah et al. (2017).

There are several issues that may contribute to a lack of sectoral coordination. One issue is that the responsibilities of the ministries/agencies are not always well defined. For example, the Disaster Management Law is noted to not provide sufficient guidance on the roles of different actors (BNPB, 2015). Responsibilities may overlap which makes it unclear who should be doing what. This can lead to tensions between sectors, and a potential ‘vacuum of responsibility’ which hinders cooperation (Djalante et al., 2013). A second issue is that there is a lack of formal mechanisms in place to support cooperation between sectors. For example, there is no mechanism in place for departments involved in disaster management to coordinate on a regular basis. Where coordination does take place it is more informal (Srikadini et al., 2018). There is also a lack of guidance on how the different sectors should integrate their work. For example, there is no framework for how spatial planning should be integrated with disaster management or climate change adaptation (Das & Luthfi, 2017; Wijaya et al., 2017). These areas are highly interrelated, and this could have significant impacts for flood management. A further issue in coordinating sectors may relate to the fragmented arrangements of the legal frameworks. It is found that there is no plan focused on flood resilience available at the national level (Handayani et al., 2019). The management of flooding is relevant to both the Water Law and the Disaster Management Law. However, how the laws relate to one another is not clear. This could pose a challenge for actors coordinating on flooding (Clegg et al., 2020).

3.2 Coordinating Vertical Governance Levels

In 1999, Indonesia moved from a centralised to a decentralised governance system. During this time, sub-national government levels (provincial, city/regency) gained greater powers and responsibilities. Responsibilities became more distributed for many work areas, including flood management. For both water management and disaster management there are various authorities located at multiple government levels, all with different duties (Dewi & van Ast, 2017; Handayani et al., 2020). This includes the state, the province and the local sub-districts (van Voorst, 2016). In decentralised governance systems, such as this, there is a need to coordinate plans and policies through vertical levels of governance (Handayani et al., 2020). Ideally, plans and actions will be aligned for consistency. However, several issues have been identified that mean vertical coordination is a challenge.

While the previous section identified that roles and responsibilities of national ministries/agencies are not always clearly set out, the same has been identified between vertical levels of governance (Dewi & van Ast, 2017; Grady et al., 2016). This can result in similar problems where it is unclear who is responsible for what. It is noted that while there are several regulations that state the need for cooperation between government levels in place, guidance provided on how this should be achieved is not explicit (Das & Luthfi, 2017; Dewi & van Ast, 2017). Furthermore, there are no formal mechanisms in place to support effective vertical coordination (Djalante & Thomalla, 2012; Handayani et al., 2019). For example, this is apparent in the arrangements for disaster management. Grady et al. (2016) identified that disaster management agencies at national and district levels suffer from a lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities. The authors also note that policies are not fully connected between governance levels. For example, sometimes provinces and districts do not always have operational plans in place which creates a disconnect.

In terms of planning, plans should be aligned throughout the levels of governance to ensure that they connect broader national goals to action at the local level. For example, Asdak et al. (2018) note that spatial plans made at the local level should be linked with the plans set out at provincial and national levels. However, they find that spatial plans are not always well coordinated. The identified reason for this is that it is not well enforced, thus does not always take place. In addition, while agendas are set at national and provincial levels, the local government level has a key role in implementation of plans (Handayani et al., 2019). However, a lack of capacity (budgets, staffing, expertise) at the local level has been recognised to have created an implementation gap, where plans are in place but they are not always fully realised at the local level. This may also impact on coordination between levels. For example, differences in capacity between national and district disaster management authorities have been identified to hinder effective vertical coordination (Das & Luthfi, 2017; Grady et al., 2016).

3.3 Coordinating Within the River Basin

Basin-wide integration is required to tackle floods (Bakker, 2009). This means that to address floods in Jakarta, coordination is required with the upstream province of West Java (Sunarharum et al., 2014). As an aid for basin-wide water management and following IRBM principles, Indonesia established river basin territories (Wilayah Sungai, WS), of which there are 133 throughout the country. A WS is defined as “one or more basins/catchments under one authority” (Ariyanti et al., 2020). Basin planning takes place for each unit, where a strategic Pola and a more detailed Rencana plans are prepared. Flood management is included in these documents (Asian Development Bank, 2016). This approach follows basic IRBM principles, that basin planning and management takes place at the basin level (Ariyanti et al., 2020). However, this approach to the management of river basins would appear to be in contention with the local government arrangements, which prevents coordination being fully achieved. Following the decentralisation of the government, as described above, local governments gained greater freedom over their own affairs (Asdak et al., 2018; Firman, 2014). This meant that local governments could address problems relevant to them directly, and processes became more efficient as a result (van Voorst, 2016). However, Firman (2014) identified that this greater autonomy also meant that local governments become ‘inward looking’ and were not always willing to, or saw the need to cooperate with one another.

Asdak et al. (2018) identified this in terms of the spatial planning system. They note that the spatial planning systems of Bogor, Depok and Jakarta are not well integrated, associated with the independence of local authorities. This creates a problem for a consistent approach to spatial planning within the Ciliwung Basin. More recently, regulation has been introduced to mandate for more integrated spatial planning between various stakeholders in Greater Jakarta, including upstream areas of Bogor and Depok (Presidential Regulation 60/2020). Due to the recent nature of the regulation it is unclear what effect this regulation has had on coordination.

Issues of coordination may also be attributed to the upstream-downstream dynamics of the flood problem within a river basin. The flood problem is most persistent in the downstream, but requires cooperation with the upstream for management. However, as flooding is not so much a pressing issue for the upstream, they have been noted to be less engaged in coordination with the downstream (Dewi & van Ast, 2017).

There are additional issues surrounding the capacities of local governments. After decentralisation, local governments gained greater responsibilities for certain affairs, including aspects of flood management. However, some local governments do not always have the capacities to manage and implement the roles they are tasked with. Some local governments were able to develop much faster than others, which has created a disparity in capacity across borders. These capacity issues are related to coordination in several ways. Firstly, low capacity may mean that there are no resources available to back local government coordination efforts (Asdak et al., 2018). Secondly, the capacity disparity between borders may mean that areas with greater capacity have greater influence than their less capable counterparts which can create an uneven playing field for cooperation (Firman, 2014). While recent studies have indicated that capacity disparities between regions are narrowing, it is suggested that more can still be done to address the unevenness of local capacities (Talitha et al., 2020).

3.4 Existing Coordination Mechanisms

River Basin Organisations (RBOs) are often suggested as a way to help overcome some of the horizontal and vertical coordination challenges within a river basin (Schmeier & Vogel, 2018; UNISDR, 2018). Therefore, focus is now turned to the mechanisms and institutions that are in place to enable and support coordination/collaboration. In Indonesia, there are several different institutions for coordination in place at different governance levels. For example, for water management at the national level, there is the National Water Council (DSDA) led by the Directorate of General Water Resources, Ministry of Public Works (the ministry responsible for water utilisation). The water council brings together ministers from various agencies, for example, planning, public works, agriculture and forestry, as well as non-government members, such as disaster management (World Bank, 2015). There is a further series of water councils at the provincial level. In addition, for each WS there is a water resources authority known as B(B)WS or Balai PSDA. In the Ciliwung, this is the BBWS for the Ciliwung and Cisadane basins. BBWS are technical implementing units of the Ministry of Public Works, and they have roles in operation and management, but also play a coordination role (World Bank, 2015). There are then TKPSDAS. These are a further type of multi-sector, multi-actor water councils and platforms for coordination at WS level that include both government and non-government actors (World Bank, 2015). The TKPSDA for the Ciliwung-Cisadane WS was involved in the preparation of the new water resources management plan for the basin by reviewing it and providing recommendations (Balai Besar Wilayah Sungai Ciliwung Cisadane, 2020). For disaster management, there is another array of platforms for coordination. At the national level there is PLANAS, the national platform for disaster risk reduction which brings together different stakeholders including ministries and agencies, civil society organisations, NGOs, private sector organisations and universities (BNPB, 2015; Djalante & Thomalla, 2012). There is also the university forum (Forum Universitas) as well as regional and village disaster risk reduction forums (Srikadini et al., 2018). For Jakarta development, there is BKSP which holds the task of planning, monitoring and coordinating development in the city (Firman, 2014; Ward et al., 2013). It also deals with cross-border related issues with West Java.

Despite this range of coordination mechanisms available, several issues have been identified with their operation. In terms of the water councils, they tend to lack authority and capacity, in particular the TKPSDAs that play a primary role in coordination at the basin level (Asian Development Bank, 2016; Dewi & van Ast, 2017). For example, it is suggested that the TKPSDAs do not have the authority to make sure that actions that are agreed on are implemented, which limits their influence on the ground (Asian Development Bank, 2016). Furthermore, it is noted that responsibilities of basin organisations are not always clearly defined (World Bank, 2015), and some organisations have overlaps in their roles. For example, both TKPSDA and BBWS have coordination roles, which may contribute to a lack of clarity (Asian Development Bank, 2016). Resource-related issues are also identified. Funding and resource issues have also been suggested to be a problem from the PLANAS national disaster platform (Grady et al., 2016). Similarly, BKSP has been noted to suffer from a lack of resources (Firman, 2014). Further, the organisation has been suggested to lack the power to make sure coordination actually happens in practice (Dewi & van Ast, 2017).

4 Conclusion

This chapter has discussed the important role of coordination for the governance of complex environmental problems, and has highlighted some of the potential challenges facing successful coordination. To illustrate, the case of the Ciliwung River Basin, Java was presented. Based on the findings of a literature review, the challenges facing effective coordination in the Ciliwung were examined. The review identified that coordination challenges exist between sectors, vertically between governance levels from national to local, and horizontally between actors within the river basin. It was found that while there are many platforms for coordination, they are not always fully effective in this role.

The review revealed several common challenges facing coordination. Firstly, a lack of clarity surrounding the roles and responsibilities of different actors was found to be a reoccurring issue associated with different aspects of coordination, including sectoral coordination and vertical coordination, as well as for different basin organisations with coordinating roles. There is a need to make sure that the different actors involved, at the national level through to the local level, are clear on the functions they hold.

Issues associated with local government also appear prominent. The independence of local governments in the decentralised system is somewhat in contention with the need to coordinate cross-border to achieve integrated river basin management. As noted previously by Firman (2014), one way to improve coordination could be to provide greater incentive for local government to coordinate with one another. There is also the issue of local government capacity. Local governments often have low capacity which may prevent them from coordinating with others. Additionally, local governments have been found to be responsible for much of the implementation of flood-related measures, but they do not necessarily have the budgets to implement them. This means that while there are plans and programmes in place, they do not always get actioned at the local level. This then creates a gap in the coordination of plans throughout vertical levels. There is a need to build the capacity of local governments in coordination and implementation.

Platforms for coordination are often held as important tools for governing transboundary basins. In the case of the Ciliwung, it has been found that it is not a lack of coordination platforms that poses a challenge, in fact, there are a considerable number of organisations that provide a coordinating function with relevance to flood management. The platforms also bring together government as well as non-government actors. The issue would appear to be with the power and capacity of these organisations to bring about productive coordination, as well as to ensure agreements made are acted upon. The effectiveness of coordination platforms for river basin management has been drawn into question elsewhere (Huitema et al., 2009). One way coordination could be improved would be to make sure that the functions of each organisation are clear, and to strengthen the existing organisations to conduct their responsibilities (Asian Development Bank, 2016).

While much discussion regarding transboundary basins focuses on coordination within the basin, this review has shown that coordination challenges are not restricted to within the basin but can occur at the national level and through levels of governance. While these lie outside the basin directly, these have the potential to impact upon the function of river basin governance and management. Spatial planning for example is an important aspect to consider in managing flooding, but vertical and horizonal coordination challenges hindering effective spatial planning then have knock on effects for flood management. As suggested by Handayani et al. (2020), improved coordination in urban development could help to achieve overall greater sustainability, and could then support overall flood risk reduction.

Addressing the coordination problems identified here could help create a more enabling environment for working together. Coordination itself will not resolve the problems if budget and capacity issues are not addressed so that implementation can occur. Pushing for more collaboration, where resources are pooled and other non-actors are involved could be a way of helping to address this complexity and associated resource issues (Watson, 2004). In addition, the challenges facing coordination identified here draw into question how greater coordination and collaboration could be achieved. For example, whether it will be possible to develop greater collaboration between local administrations considering the lack of will and funding issues, or whether greater formal regulation will be required to initiate it. The decentralised governance system has allowed for greater independence of local governments, but this has not created an environment where coordination and collaboration easily exist. It will be of interest to observe the impacts of the recently implemented spatial planning regulation which presents a top-down driver for coordination, and the effects this has on working together.

This case study of governance arrangements in the Ciliwung River Basin has highlighted the complexity of achieving the coordination required to address environmental problems. Coordination is required across multiple dimensions. While coordination is not the only barrier to the governance of environmental problems, it is a prevalent and complex problem that should be considered carefully. While this study focused upon flooding, these findings may be of relevance to the governance of other environmental concerns.

The findings and conclusions expressed in this chapter are based on an extensive review of the previous studies. These will inform further empirical research that is being conducted by the same project team, who is engaging with key actors in the Ciliwung River Basin to explore how these coordination challenges can be overcome to strengthen flood risk management arrangements.

Notes

References

Abidin, H. Z., Andreas, H., Gumilar, I., Fukuda, Y., Pohan, Y. E., & Deguchi, T. (2011). Land subsidence of Jakarta (Indonesia) and its relation with urban development. Natural Hazards, 59, 1753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9866-9

ACAPS. (2020). Indonesia floods – Briefing note 10th January 2020. ACAPS.

Akhmouch, A., & Calavreul, D. (2019). Flood governance: A shared responsability. An application of the OECD Principles on Water Governance to Flood Management, Draft edn. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Ariyanti, V., Edelenbos, J., & Scholten, P. (2020). Implementing the integrated water resources management approach in a volcanic river basin: A case study of Opak sub-basin, Indonesia. Area Development and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2020.1726785

Asdak, C., Supian, S., & Subiyanto. (2018). Watershed management strategies for flood mitigation: A case study of Jakarta’s flooding. Weather and Climate Extremes, 21(September), 117–122.

Asian Development Bank. (2016). River Basin management planning in Indonesia: Policy and practice. Philippines.

Bakker, M. H. N. (2009). Transboundary river floods and institutional capacity. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 45(3), 553–566.

Balai Besar Wilayah Sungai Ciliwung Cisadane. (2020). Sinkronisasi Program & Kegiatan Penglolaan SDA WS Ciliwung Cisadane. PU. https://sda.pu.go.id/balai/bbwscilicis/sinkronisasi-program-kegiatan-pengelolaan-sda-ws-ciliwung-cisadane/. Accessed 3 Nov 2021.

BNPB. (2015). Indonesia’s Disaster Risk Management Baseline Status Report 2015. Towards Identifying National and Local Priorities for the Implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030). Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana/ National Disaster Management Authority,

Cambridge Dictionary. (2022). Coordination. Cambridge Dictonary. dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/coordination, Online.

Cao, A., Esteban, M., Valenzuela, V. P. B., Onuki, M., Takagi, H., Thai, N. D., & Tsuchiya, N. (2021). Future of Asian deltaic megacities under sea level rise and land subsidence: Current adaptation pathways for Tokyo, Jakarta, Manila, and Ho Chi Minh City. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 50(June 2021), 87–97.

Clegg, G., Haigh, R., Amaratunga, D., & Rahayu, H. P. (2020). Transboundary river and flood governance: A comparison of arrangements in Indonesia and Europe. University of Huddersfield Unpublished Project Report.

Clegg, G., Haigh, R., Amaratunga, D., Rahayu, H. P., Karunarathna, H. U., & Septiadi, D. (2021). A conceptual framework for flood impact mitigation through transboundary river management. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 11(3), 880–888.

Das, A., & Luthfi, A. (2017). Disaster risk reduction in post-decentralisation Indonesia: Institutional arrangements and changes. In R. Djalante, M. Garschagen, F. Thomalla, & R. Shaw (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction in Indonesia: Process, challenges and issues. Springer.

Dewi, B. R. K., & van Ast, J. A. (2017). Institutional arrangements for integrated flood management of the Ciliwung-Cisadane River Basin, Jakarta metropolitan area, Indonesia. In M. P. van Dijk, J. Edelenbos, & K. van Rooujen (Eds.), Urban governance in the realm of complexity. Practical Action Publishing.

Dieperink, C., Mees, H., Priest, S., Ek, K., Bruzzone, S., Larrue, C., & Matczak, P. (2018). Managing urban flood resilience as a multilevel governance challenge: An analysis of required multilevel coordination mechanisms. Ecology and Society, 21(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09962-230131

Djalante, R., & Thomalla, F. (2012). Disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in Indonesia: Institutional challenges and opportunities for integration. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 3(2), 166–180.

Djalante, R., Holley, C., Thomalla, F., & Carnegie, M. (2013). Pathways for adaptive and integrated disaster resilience. Natural Hazards, 69, 2105–2135.

Dwirahmadi, F., Rutherford, S., Phung, D., & Chu, C. (2019). Understanding the operational concept of a flood-resilient urban community in Jakarta, Indonesia, from the perspectives of disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation and development agencies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3993). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203993

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2011). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29.

Evans, J. P. (2012). Environmental governance. Routledge introductions to the environment. Routledge.

Firman, T. (2014). Inter-local-government partnership for urban management in decentralizing Indonesia: From below or above? Kartamantul (greater Yogyakarta) and Jabodetabek (greater Jakarta) compared. Space and Polity, 18(3), 215–232.

Grady, A., Gersonius, B., & Makarigakis, A. (2016). Taking stock of decentralised disaster risk reduction in Indonesia. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 16(9), 2145–2157.

Handayani, W., Fisher, M. R., Rudiarto, I., Setyono, J. S., & Foley, D. (2019). Operationalizing resilience: A content analysis of flood disaster planning in two coastal cities in Central Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 35(101073).

Handayani, W., Chigbu, U.E., Rudiarto, I., Putri, I.H.S. (2020). Urbanization and increasing flood risk in the northern coast of Central Java-Indonesia: An assessment towards better land use policy and flood management land (9):343.

Hellman, J. (2015). Living with floods and coping with vulnerability. Disaster Prevention and Management, 24(4), 468–483.

Huitema, D., Mostert, E., Egas, W., Moellenkamp, S., Pahl-Wostl, C., & Yalcin, R. (2009). Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-)management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecology and Society, 14(1), 26.

Kefi, M., Mishra, B. K., Masago, Y., & Fukishi, K. (2020). Analysis of flood damage and influencing factors in urban catchments: Case studies in Manila, Philippines, and Jakarta, Indonesia. Natural Hazards, 104, 2461–2487.

Mardiah, A. N. R., Lovett, J. C., & Evanty, N. (2017). Toward integrated and inclusive disaster risk reduction in Indonesia: Review of regulatory frameworks and institutional networks. In R. Djalante, M. Garschagen, F. Thomalla, & R. Shaw (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction in Indonesia: Progress, Challenges and Issues. Springer International.

Margerum, R. D., & Robinson, C. J. (2015). Collaborative partnerships and the challenges for sustainable water management. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 12(February 2015), 53–58.

Moe, I. R., Kure, S., Januriyadi, N. F., Farid, M., Udo, K., Kazama, S., & Koshimura, S. (2017). Future projection of flood inundation considering land-use changes and land subsidence in Jakarta, Indonesia. Hydrological Research Letters, 11(2), 99–105.

Mulyana, W., & Prasojo, E. (2020). Indonesia urban water governance: The interaction between the policy domain of urban water sector and actors network. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 15(2), 211–218.

Presidential Regulation. (60/2020). Tentang rencana tata ruang kawasan perkotaan jakarta, bogor, depok, tangerang, bekasi, puncak, dan cianjur. 60/2020. [Concerning spatial plan for the urban area of jakarta, bogor, depok, tangerang, bekasi, puncak, and cianjur (in Bahasa Indonesia)]

Remondi, F., Burlando, P., & Vollmer, D. (2016). Exploring the hydrological impact of increasing urbanisation on a tropical river catchment of the metropolitan Jakarta, Indonesia. Sustainable Cities and Society, 20, 210–221.

Savenije, H. H. G., & van der Zaag, P. (2000). Conceptual framework for the management of shared river basins; with special reference to the SADC and EU. Water Policy, 2(2000), 9–45.

Schmeier, S., & Vogel, B. (2018). Ensuring long-term cooperation over transboundary water resources through joint river basin management. In S. Schmutz & J. Sendzimir (Eds.), Riverine ecosystem management: Science for governing towards a sustainable future. Springer Open.

Skoulikaris, C., & Zafirakou, A. (2019). River basin management plans as a tool for sustainable Transboundary River basins’ management (pp. 1–14). Environmental Science and Pollution Research. https://doi-org.libaccess.hud.ac.uk/10.1007/s11356-019-04122-4

Srikadini, A. G., Hilhorst, D., & van Voorst, R. (2018). Disaster risk governance in Indonesia and Myanmar: The practice of co-governance. Politics and Governance, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i3.1598

Sunarharum, T. M., Sloan, M., & Susilawati, C. (2014). Re-framing planning decision-making: Increasing flood resilience in Jakarta. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 5(3), 230–242.

Talitha, T., Firman, T., & Hudalah, D. (2020). Welcoming two decades of decentralization in Indonesia: A regional development perspective. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(5), 690–708.

Texier, P. (2008). Floods in Jakarta: When the extreme reveals daily structural constraints and mismanagement. Disaster Prevention and Management, 17(3), 358–372.

Tjasyono, H. K. B., Gernowo, R., Sri Woro, B. H., & Ina, J. (2008). The character of rainfall in the Indonesian monsoon. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Equatorial Monsoon System.

UNISDR. (2018). Implementation guide for addressing water-related disasters and transboundary cooperation: Integrating disaster risk management with water management and climate change adaptation. Words into Action Guidelines. United Nations.

Siswanto, van Oldenborgh, G. J., van der Schrier, G., Lenderink, G., & van den Hurk, B. (2015). Trends in high-daily precipitation events in Jakarta and the flooding of January 2014. In S. C. Herring, M. P. Hoerling, J. P. Kossin, T. C. Peterson, & P. A. Stott (Eds.), Explaining extreme events of 2014 from a climate perspective (Vol. 96). American Meteorological Society.

van Voorst, R. (2016). Formal and informal flood governance in Jakarta, Indonesia. Habitat International, 52, 5–10.

Ward, P. J., Pauw, W. P., van Buuren, M. W., & Marfai, M. A. (2013). Governance of flood risk management in a time of climate change: The cases of Jakarta and Rotterdam. Environmental Politics, 22(3), 518–536.

Watson, N. (2004). Integrated river basin management: A case for collaboration. International Journal of River Basin Management, 2(4), 243–257.

Wiering, M., Verwijmeren, J., Lulofs, K., & Feld, C. (2010). Experiences in regional cross border co-operation in river management. Comparing three cases at the Dutch-German border. Water Resources Management, 24, 2647–2672.

Wijaya, N., Bisri, M. B. F., Aritenang, A. F., & Mariany, A. (2017). Spatial planning, disaster risk reduction, and climate change adaptation integration in Indonesia: Progress, challenges, and approach. In R. Djalante, F. Thomalla, M. Garschagen, & R. Shaw (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction in Indonesia: Progress, challenges and issues. Springer.

World Bank. (2015). Toward efficient and sustainable river basin operational services in Indonesia. World Bank.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (Project Reference: NE/S003282/1), the Newton Fund, the UK Economic and Social Research Council, and the Ministry of Research, Technology & Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia (RISTEK-BRIN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Clegg, G., Haigh, R., Amaratunga, D., Rahayu, H.P. (2023). Coordination Challenges Facing Effective Flood Governance in the Ciliwung River Basin. In: Triyanti, A., Indrawan, M., Nurhidayah, L., Marfai, M.A. (eds) Environmental Governance in Indonesia. Environment & Policy, vol 61. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15904-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15904-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15903-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15904-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)