Abstract

Blue foods play a central role in food and nutrition security for billions of people and are a cornerstone of the livelihoods, economies, and cultures of many coastal and riparian communities. Blue foods are extraordinarily diverse, are often rich in essential micronutrients and fatty acids, and can be produced in ways that are more environmentally sustainable than terrestrial animal-source foods. Yet, despite their unique value, blue foods have often been left out of food system analyses, discussions and solutions. Here, we focus on three imperatives for realizing the potential of blue foods: (1) Bring blue foods into the heart of food system decision-making; (2) Protect and develop the potential of blue foods to help end malnutrition; and (3) Support the central role of small-scale actors in fisheries and aquaculture.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Debates and decisions about food systems generally focus on agriculture and livestock. Blue foods – fish, invertebrates, algae and aquatic plants captured or cultured in freshwater and marine ecosystems – are perennially neglected (Bennett et al. 2021). Yet, blue foods play a central role in food and nutrition security for billions of people and may be ever more important as the world seeks to create just food systems that support the health of people and the planet (HLPE 2014; Bennett et al. 2018; FAO 2020a; Hicks et al. n.d.; Golden et al. 2021). It is thus paramount that governments bring blue food systems into their food-related decision-making.

Last year, the UN Committee of World Food Security High Level Panel of Experts called for a transformation of the food system, moving “from a singular focus on increasing the global food supply through specialized production and export to making fundamental changes that diversify food systems, empower vulnerable and marginalized groups, and promote sustainability across all aspects of food supply chains, from production to consumption” (HLPE 2020). Properly understood and managed, many blue foods are profoundly suited to that shift.

The blue food portfolio is highly diverse. There are more than 3000 species of marine and freshwater animals and plants used for food (Golden et al. 2021; Thilsted et al. 2016). Blue food systems are supported by a wide range of ecosystems, cultures and production practices – from large-scale trawlers on the high-seas to small-scale fishponds integrated within agricultural systems – supporting access to nutritious food for communities through global and local markets alike. This diversity supports resilience that can help local food systems withstand shocks like COVID-19 and climate extremes (Troell et al. 2014; Béné 2020; Love et al. 2021) and offers many possibilities for governments and communities seeking to build food systems that are healthy, sustainable, and just.

Blue foods can be a cornerstone of good nutrition and health. Many of them are rich in bioavailable micronutrients that help prevent maternal and infant mortality, stunting, and cognitive deficits. And blue foods can be a healthier animal-source protein than terrestrial livestock: they are rich in healthy fats and can help reduce obesity and non-communicable diseases. In many parts of the world, blue foods are also more accessible and affordable than other animal-source foods (Ryckman et al. 2021a, b). Aquatic plants, including seaweeds, are a traditional presence in diets in the Asia-Pacific region and may offer a variety of possibilities for low-carbon, nutritious food. Coastal and riparian Indigenous Peoples, from the Arctic to the Amazon, have traditionally had among the highest per capita aquatic food consumption rates in the world (Bayley 1981; Cisneros-Montemayor et al. 2016).

Blue foods generally have smaller environmental footprints than many other animal-source foods (Gephart et al. 2021a). However, across a diverse sector, the details matter: greenhouse gas emissions and wildlife and biodiversity impacts can be quite high for some blue food systems, such as bottom trawling or aquaculture systems with low feed efficiencies, especially when they are poorly sited or poorly managed. But many fisheries and aquaculture systems offer footprints that are much smaller than that of beef, with the potential to be improved further (Gephart et al. 2021a). Unfed aquaculture (such as filter-feeding shellfish and seaweeds) also has the potential to improve the water quality of the environment it occupies (Naylor et al. 2021a).

Blue foods are important to livelihoods in many vulnerable communities. The FAO estimates that about 800 million people make their living in blue food systems (FAO 2012), mostly in small-scale fisheries and aquaculture. These systems produce a wide variety of blue foods, supporting healthy diets and resilience in the face of climate change and market fluctuations.

To capitalize on the potential of blue foods, decision-makers must address significant challenges. Wild capture fisheries, both marine and freshwater, need to be better managed (Hilborn et al. 2020; Melnychuk et al. 2021), as many fish stocks have become severely depleted and some technologies have high environmental footprints. Although aquaculture is becoming increasingly sustainable, the growing use of feed in some sectors is putting pressure on the environment through overfishing, deforestation for feed crops and intensification of agricultural production. Intensification of aquaculture can concentrate nutrient pollution and exacerbate risks associated with pathogens and high dependence on antibiotics (Naylor et al. 2021a; Henriksson et al. 2018).

Environmental stressors can also limit blue food production. Climate change will increasingly affect the health and productivity of fish stocks and aquatic ecosystems (FAO 2018) with implications for food security, livelihoods and economies worldwide, and especially in wild capture fisheries in Africa, East and South Asia, and small island developing states (Tigchelaar et al. 2021; Golden et al. 2016). Other kinds of pollution, from agricultural nutrient runoff to plastics, further threaten productivity and the safety of foods harvested from polluted waters (Bank et al. 2020; Garrido Gamarro et al. 2020).

Like all food systems, blue food systems are beset by inequities. Wealth-generating activities are often favored over those important to nutrition and health, livelihoods and culture. The aquatic resource management systems, knowledge and rights of Indigenous Peoples and traditional small-scale fisherfolk have often been undermined or overlooked in fisheries, water management and ocean governance (Ratner et al. 2014). Although blue food value chains employ roughly equal numbers of men and women (FAO 2020a), their roles, influence over value chains, and benefits can be highly unequal. Progress toward gender equality is critical for the development of more equitable and efficient blue food systems (Hicks et al. n.d.; Lawless et al. 2021).

Blue foods are globally the most traded food products – for developing countries, net revenues from trade of blue foods exceed those of all agricultural commodities combined (Gephart and Pace 2015; Sumaila et al. 2016; FAO 2020b). Global supply chains are complex and often opaque, however, making it difficult or impossible for buyers to ascertain environmental impacts and human rights abuses in production. In some places, the harvesting and trade of fish for high monetary-value global markets have undermined production that is important for local food security and livelihoods (Hicks et al. 2019).

There is every reason to expect that total demand for blue foods will grow substantially in the years ahead – as population and incomes increase, and as attention toward healthy and sustainable food expands (Naylor et al. 2021b) – with growth in supply primarily expected to come from aquaculture (Naylor et al. 2021a). If produced responsibly, blue foods have essential roles to play in ending malnutrition and in building healthy, nature-positive and resilient food systems, including for people living on lands that are marginal for agricultural production (particularly forests, wetlands and small islands), many of whom are Indigenous (Azam-Ali et al. 2021). Realizing that potential, however, will require that governments be thoughtful about how to develop those roles. Here, we focus on three central imperatives for policymakers:

-

I.

Integrate blue foods into decision-making about food system policies, programs and budgets, so as to enable effective management of production, consumption and trade, as well as interconnections with terrestrial food production;

-

II.

Understand, protect and develop their potential in ending malnutrition, fostering the production of accessible, affordable nutritious foods; and

-

III.

Support the central role of small-scale actors, with governance and finance that are responsive to their diverse needs, circumstances and opportunities.

The Bangladesh Story

The proliferation of diverse, freshwater aquaculture supply chains in Bangladesh in recent decades illustrates the potential for blue foods to meet domestic demand, improve food and nutrition security, and reduce rural poverty (Hernandez et al. 2018). This “hidden aquaculture revolution” has involved the participation of hundreds of thousands of small- to medium-scale actors along the supply chain, acting independently and in response to urbanization, growing incomes, and rising fish demand. Approximately 94% of the fish produced in freshwater aquaculture in Bangladesh is directed towards domestic markets and is not traded internationally. Although mostly small-scale, freshwater aquaculture systems have become increasingly intensive and commercial in their operations (Belton et al. 2018). Aquaculture growth and its contribution to food and nutrition security in Bangladesh have resulted from public investment in infrastructure, a positive business environment for small- and medium-size entrepreneurs, and ‘light touch’ government control over the types of systems and species produced (Hernandez et al. 2018).

2 Policy Recommendations

2.1 Bring Blue Foods into the Heart of Food System Decision-Making

2.1.1 The Problem: Fisheries and Aquaculture Are Typically Ignored in the Management of Food Systems

Blue foods are deeply interconnected with the rest of the food system – in diets, in supply chains, and in the environment. Aquatic and terrestrial foods appear on the same plate and are often substitutes for each other in household food choices. Capture fisheries provide feed inputs for aquaculture and livestock; terrestrial crops provide feed inputs for aquaculture. Excess nutrients from agriculture and aquaculture can pollute rivers and cause coastal dead zones, undermining fisheries; cultivation of filter-feeding fish and seaweeds takes up nutrients and, if properly managed and scaled, can help protect ecosystem health. Genetic advances in crops and livestock have had positive spillover effects on aquaculture through selection and breeding and through improvements in nutritional performance and feed efficiency.

Yet, blue foods are generally ignored in food system discussions and decision-making (Bennett et al. 2021). Blue foods receive little attention in development assistance – the World Bank, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and other major development funders have largely neglected the roles of fish, shellfish and aquatic plants in human nutrition and health. Blue foods also tend to be left out of food system policymaking at the national level (Koehn et al. 2021). Ministries or agencies dedicated to capture fisheries and aquaculture tend to manage them as a natural resource, with a focus on economic interests – production and trade. In many countries, the result is that both fisheries and aquaculture are managed with an emphasis on high-monetary-value, export-oriented production. That orientation is reinforced by the market and naturally favors investments in innovations and enterprises that offer the highest financial return. Critical welfare functions are often neglected; indeed, fishery agencies often lack the mandate to address the potential contributions of blue foods to food security and public health, to livelihoods and communities, and to cultural traditions and diets.

When fisheries and aquaculture are siloed and managed as a natural resource, policymakers miss vital opportunities for advancing their goals for nutrition, sustainability, resilience, and livelihoods, and they make unwitting trade-offs among those interests. Fisheries that have sustained communities for generations are depleted by distant water fleets or outcompeted in the market by large volumes of inexpensive farmed fish. The farming of species that could remedy pressing nutrient deficiencies remains undeveloped because management and investment are directed to high-revenue products. Small-scale producers who are central to local diets, livelihoods and community resilience lose out to large commercial concessions.

The African Great Lakes

The small pelagic fisheries of the African Great Lakes region illustrate the opportunities in bringing blue foods into food system policymaking. These fisheries produce huge volumes of affordable, micronutrient-rich food traded throughout the region, but they have been given low priority for investment and management because they are seen as having low economic value. Food system policymaking approaches could include investments to (a) reduce post-harvest loss, which can be substantial, and improve food quality and safety; (b) strengthen domestic and intra-regional trade institutions to enhance small-scale trader market access; (c) address the challenges, risks and opportunities of female fish traders, who comprise a substantial portion of the post-harvest sector; and (d) manage trade-offs between sale for animal feed industries and that for direct human consumption.

2.1.2 The Solution: Governments Should Fully Integrate Blue Foods into their Governance of Food Systems

The potential of blue foods will only be realized if they are brought into food system decision-making. That requires integrated governance, systematic inclusion in policy, and a basic change in the way we think about fish. Specifically, governments should:

-

(a)

Create a governance structure that integrates green and blue

Governments should create a Ministry of Food or other structure that can govern the entire food system, managing synergies and trade-offs in production, consumption and trade. Ministries of agriculture and of fisheries typically focus on production – generally on increasing volume – and often are captured by entrenched interests. A Ministry of Food or similar entity could manage the disparate interests of producers, consumers, and other stakeholders for improved nutritional, environmental, economic, and social outcomes. It could, for example, manage production and consumption to create markets for more nutritious species (see Sect. 2.2). It could also expand the capabilities of small-scale producers, through investment and the allocation of resource rights to support livelihoods and community resilience (see Sect. 2.3). More broadly, it enables decision-makers to govern blue foods as a food system, and to ensure blue foods are fully included in all food system policies.

-

(b)

Govern blue foods as a food system

At the most basic level, integrating blue foods into food system decision-making also recognizes that fisheries and aquaculture should themselves be managed as food systems – they should be managed to deliver society’s goals for nutrition, health and equity, as well as for economics and sustainability. Government policy and management should embrace all aspects of the blue food sector – including fisheries, aquaculture development, distribution, exports and imports, and consumption.

Promoting a systems approach means that governments can ensure that nutrient-rich aquatic foods are available and affordable to those for whom they are most important, both nutritionally and culturally. It can work across the value chain to identify and address the many threats to the supply of blue foods, from overfishing to pollution to waste and loss in harvesting, processing and distribution (see Sect. 2.2). It can build a system that is just, ensuring equitable participation in production, accessibility for consumption, and broad representation in decision-making. By managing blue foods as a system, governments can also create policies and incentives across the value chain to shift both production and consumption to species and technologies that have lighter footprints and to foster diversity in production systems.

Looking at the whole system also enables the government to make public investments where markets fail. Private investment goes to blue food systems and enterprises that offer high financial returns. Governments can allocate public funds to develop innovations in fisheries and aquaculture that offer lower returns but are important for nutrition, livelihoods, and sustainability, and it can provide capital for small- and medium-sized enterprises to take those innovations to scale.

To realize this vision, governments will need to collect data that enable good decisions – including data that enable the monitoring of fisheries and supply chains, that capture the vital diversity of species that are produced and consumed, that survey the demographic diversity of participants in the sector, and that reflect the frequently profound heterogeneity in consumption across different regions of the country and between different ethnic and religious groups. They will also need to redesign policies to enable and incentivize the capabilities of key actors – from producers to consumers – to adopt transformative practices in the food system as a whole, in value chains, and in the places where they live (see Sect. 2.3).

-

(c)

Include blue foods in all food system policies

Structural reform must be followed by policy inclusion – governments should integrate blue foods into the policies that regulate, guide and support the food sector. Government strategies to meet the Human Right to Food, for example (see Sect. 2.2), should embrace the potential of blue foods to offer accessible, affordable sources of key nutrients. Dietary guidelines should include the nutritional contributions of different blue foods, so as to help consumers understand their value for addressing nutrient deficiencies and obesity, diabetes and coronary disease. Safety net programs for children and pregnant and lactating women should also include blue foods, as fish can be a rich source of essential micronutrients for those most vulnerable populations, helping to prevent stunting and cognitive deficits. The food systems and food sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples must be supported.

Including blue foods in policymaking for the food system allows governments to better manage the interconnections between terrestrial and aquatic food systems. That includes the regulation of agricultural and inland aquaculture runoff and other land-based pollution that can undermine coastal fisheries and marine aquaculture, such as nutrients that cause coastal dead zones and toxins that can compromise food safety. Governments can also better manage the allocation of crops and fish to competing uses – for food or feed – and support the development of a circular economy in which wastes or by-products from one part of the food system are used as feed inputs for another.

2.2 Protect and Develop the Potential of Blue Foods to Help End Malnutrition

2.2.1 The Problem: Blue Food Systems Are Not Managed for Nutrition

Many blue foods contain high concentrations of bioavailable minerals and vitamins, essential fatty acids (in particular, EPA and DHA), and animal protein (Thilsted et al. 2016) – globally, roughly 8% of zinc and iron, 13% of protein, and 27% of vitamin B12 are derived from aquatic foods (Golden et al. 2021). Blue foods can therefore make key contributions to diet-related health challenges. They can reduce micronutrient deficiencies that lead to disease; improve heart, brain and eye health by uniquely providing omega-3 fatty acids; and replace the consumption of less healthy red and processed meats (Golden et al. 2021). The micronutrient contributions of blue foods are especially important for childhood development, pregnant women and women of childbearing age (Kawarazuka and Béné 2011; Bogard et al. 2015; Starling et al. 2015), and can reduce nutritional inequities for girls and women (Golden et al. 2021).

Not all fish are equal. For example, a single serving of small indigenous species in Bangladesh, eaten whole, contributes more than five times as much vitamin B12 as a single serving of tilapia fillet (Thilsted et al. 2016). Which blue foods are on a plate, and in what form, therefore matters as much as the amount of food (Golden et al. 2021; Hicks et al. 2019). Yet, blue food policy often considers blue foods only as a protein source, which neglects the nutrient diversity of fish (in terms of micronutrients and fatty acids) and excludes the contributions of aquatic plants altogether. In the Bangladesh case discussed above, for example, growth in (farmed) fish consumption has led to an increase in total protein consumption, but also a decrease in consumption of certain micronutrients, highlighting the challenge of balancing high nutrient content provided by small native fish with employment and revenue generation offered by tilapia and pangasius production (Bogard et al. 2017). Adopting a nutrition-sensitive approach to aquaculture and fisheries, rather than just a production focus, can address these issues (Bennett et al. 2021; Thilsted et al. 2016; Gephart et al. 2021b).

In many countries, ministries manage blue foods for their wealth-generating benefits, focusing policy on high economic value blue food production, often for export. Such a focus risks undermining the critical welfare functions of blue foods by neglecting the nutritional characteristics, livelihood contributions, accessibility, and cultural patterns of blue food consumption (Bennett et al. 2021; Hicks et al. n.d.; Thilsted et al. 2016; Hicks et al. 2019). Nutrient-dense blue foods are regularly exported from nutritionally vulnerable countries to serve either as a high-quality product for wealthy consumers or to be reduced to fishmeal to feed farmed fish for high-income countries (Isaacs 2016). Orientation towards export markets not only affects coastal and riparian populations, but also inland communities who have historically depended on richly nutritious dried or smoked fish transported from the coast (Gordon et al. 2013).

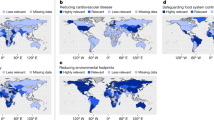

The quantity, quality and safety of blue food supply are threatened by food loss and waste (amounting to 35% of fish harvested globally (FAO 2020a)), management failures (including overfishing and Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated fishing), environmental degradation, and climate change (FAO 2018). It is estimated that declines in marine fish catch over the next three decades could subject an additional 845 million people (11% of the world’s population) to vitamin A, zinc, or iron deficiencies (Golden et al. 2016). Though all of these pressures occur globally, their effects are highest and most strongly felt in tropical and low-income countries with high dependence on blue foods for nutrition and health, livelihoods and income (Tigchelaar et al. 2021; Golden et al. 2016).

Finally, blue food policy misses opportunities to support nutrition goals when it fails to address unequal distribution of the benefits from blue food systems or the concentration of power. Women, in particular, are underrepresented in policies and decision-making (Hicks et al. n.d.; Lawless et al. 2021; Udo and Okoko 2014). Where gender equality is lacking, blue foods are less affordable (Hicks et al. n.d.) and blue food waste and losses are greater (Kaminski et al. 2020).

2.2.2 The Solution: Sustain and Enhance the Nutritional Benefits of Blue Food Systems

To manage blue food systems for the benefit of nutrition and health, governments should:

-

(a)

Recognize the centrality of the right to food in blue food trade and domestic policy

The right to food states that everyone is entitled to adequate, accessible and safe food that corresponds to their cultural traditions in a fulfilling and dignified manner (Fakhri 2020). A Right to Food means that governance of and investment in blue food systems should seek balance between economic opportunities and local rights to food provisioning (Bennett et al. 2021; Hicks et al. n.d.), aiming to sustain and innovate with the full diversity of species, production and harvest methods, product forms and distribution channels in mind (Golden et al. 2021). Recognizing the right to food requires taking a food systems approach in which nutrition, sustainability, climate-resilience and equity can be considered together (see Sect. 2.1) and which ensures that all actors are represented, including through engagement with grass-roots and civil society organizations (see Sect. 2.3) (Bennett et al. 2021; Hicks et al. n.d.). Recognizing the food rights of Indigenous Peoples who harvest aquatic foods is of particular importance, whether such Peoples have Nation status or not. At a national level, blue foods should explicitly be included in food and nutrition policy (see Sect. 2.1) (Bennett et al. 2021; Thilsted et al. 2016; Koehn et al. 2021). Internationally, blue foods should be positioned as a vital food source in the context of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, health national adaptation plans (HNAPs), and other international efforts to alleviate malnutrition (Bennett et al. 2021).

-

(b)

Harness the nutritional diversity of blue foods

Governments should ensure that the nutritional potential of blue foods serves to improve the health and diets of nutritionally vulnerable people. They should recognize and harness the diversity of local blue food nutritional profiles, preparation methods and dietary practices (Hilborn et al. 2020).

Governments should manage capture fisheries so as to optimize them for nutritional benefits, not just for maximum sustainable yield, which can uncover opportunities to diversify fish production without increasing pressure on existing stocks (Golden et al. 2021; Bernhardt and O’Connor 2021). Aquaculture development should foster the sustainable production of native small fish species that can supply context-specific nutrient needs. As an example, mola, a fish species from the Gangetic floodplains, can easily be produced in homestead ponds and offers 80 times more vitamin A than commonly farmed silver carp (Thilsted et al. 2016).

Governments should evaluate exports and licenses to distant water fleets to ensure that they don’t compromise nutritional goals. In some cases (e.g., Namibia), retaining just a small portion of current exports could meet local nutrition goals (Hicks et al. 2019), though this requires infrastructure to support equitable distribution and access to blue foods locally (see Sect. 2.3).

Public health policies and investments focused on reducing malnutrition should include blue foods in programs to address the specific nutritional needs of pregnant and lactating women, young children and the elderly – with appropriate consideration of food safety and pollutants – as was done with the introduction of dried small fish powder in Myanmar to support children’s health (Dried small fish powder provides opportunity for child health in Myanmar 2020).

-

(c)

Halt loss of nutrients from blue food systems

To ensure that blue foods important for nutrition are available, accessible and affordable, governments should take steps to reduce losses in the system. Improved processing methods can preserve and concentrate nutrients and increase availability, as well as improve nutritional quality (Siddhnath et al. 2020).

In many places, better management of capture fisheries through harvest controls or spatial restrictions, for example, can restore fish stocks and increase yields (Hilborn et al. 2020; Melnychuk et al. 2021; Anderson et al. 2018). Better regulation of economic development in floodplains, riparian, coastal, and ocean ecosystems can help protect blue food production and reduce risks to food safety (Niane et al. 2015; de Oliveira Estevo et al. 2021).

Fisheries and aquaculture policy should also anticipate and adapt to projected impacts from climate change (FAO 2018; Tigchelaar et al. 2021). Governments should consider nature-based solutions like mangrove and seagrass restoration and restorative aquaculture that can help strengthen the resilience of aquatic ecosystems (Gattuso et al. 2018; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2019). Additional climate adaptation options are context-specific, but include shifting to offshore resources (McDonald and Torrens 2020), devising climate-smart agreements for transboundary resources (Oremus et al. 2020) and investing in climate information systems, including early warning systems for extreme events (Cinner et al. 2018; Turner et al. 2020). Place-based responses to climate change are particularly important for Indigenous Peoples whose cultures and identities are closely linked to their local environments (Whitney et al. 2020).

-

(d)

Improve the distributional equity of blue food production and consumption

Participation in activities along the value chain is often socially differentiated; for example, men dominate blue food production and women blue food processing. Governments thus need to collect data on what roles, from fish producers to post-harvest processors, traders, and consumers, different groups in society hold and why. When divisions of labor exist because of unequal opportunities to participate across the value chain, they are likely to result in distributional and nutritional inequities (Udo and Okoko 2014). Investments to address the drivers of unequal opportunities, such as through strengthening women’s empowerment, are known to lead to improvements in outcomes for women and their families. For example, in Zambia, strategies to uncover underlying structural barriers that limit participation, such as unequal norms and attitudes, increased women’s participation in production processes, and their control over resources (Kaminski et al. 2020). Governments need to ensure that the full diversity of actors, across social groups, including gender, class, and ethnicity, and along the value chain and scale of production, are fairly represented in decision-making processes (Hicks et al. n.d.) (see Sect. 2.3). In addition, governments should recognize subnational differences in nutritional vulnerability and blue food access in national policy and align subnational policies and instruments with nutritional goals.

2.3 Support the Central Role of Small-Scale Actors in Fisheries and Aquaculture

2.3.1 The Problem: Limited Recognition and Support for the SSFA Sector in Supporting Equitable and Sustainable Food Systems

Small-scale fisheries and aquaculture (SSFA) have been marginalized in dialogues about sustainable and equitable food system transformation, despite being central to it in many contexts (Bennett et al. 2021). SSFA play a key role in supplying nutrition and supporting local economies in many countries. They produce more than half of the global fish catch and contribute over two-thirds of aquatic foods destined for direct human consumption (FAO 2020a), with the potential for lower environmental footprints (e.g., lower fuel use than in large-scale operations (Gephart et al. 2021a)). In addition, the value chains that process and sell their products support about 800 million full- and part-time jobs, half of which are occupied by women (FAO 2012, 2020a). SSFA produce a high diversity of aquatic foods. This diversity underpins healthy diets, and resilience in the face of shocks, climate and market changes (Hicks et al. 2019; Gephart et al. 2021b; Bennett et al. 2020; Campbell et al. 2021). SSFA also contribute to intra-regional trade, especially in smoked and dried products, which can have more direct impacts on food security and poverty alleviation than the globalized system (Béné et al. 2010).

SSFA worldwide face a growing range of threats and challenges, including resource over-exploitation, habitat degradation, poor political representation, market-driven competition for resources (e.g., patterns of trade and foreign fishing), assumed links between informality and illegality (Song et al. 2020), climate change (Monnier et al. 2020), and shocks such as the current COVID-19 pandemic (Bennett et al. 2020; Farmery et al. 2021; Short et al. 2021). Cumulatively, SSFA are being ‘squeezed out’ of the spaces they occupy on the land-water margins by other more powerful sectors, such as tourism, residential and industrial land use, oil and gas exploration, industrial fisheries and aquaculture (Cohen et al. 2019). Within SSFA, inequitable access to resources and opportunities and limited gender and social inclusion are key threats. Indigenous Peoples whose lands and waters have been colonized by others, and whose harvesting activities tend to be small-scale, continue to be marginalized by public policy. Finally, pervasive data and monitoring limitations pose major challenges to understanding the status of SSFA (Pauly and Zeller 2016), as a lack of data leads to underestimating SSFA contributions and marginalizing SSFA in policy and decision-making, while aggregated and categorical data fail to represent the diversity of SSFA actors and benefits.

Governments and policies predominantly focus on industrialized, large-scale fisheries and aquaculture, leading to a lack of voice and support for SSFA. One reason for this persistent neglect is that policymakers struggle with the diversity, dynamism and perceived informality of SSFA and their associated cultures (Hicks et al. n.d.). Most policies affecting the sector make unrealistic assumptions that SSFA are a homogenous group limited to producers (Gelcich et al. 2018; Johnson 2006). In contrast, the sector is extraordinarily diverse along many dimensions (Short et al. 2021). Successful transformations of SSFA require supporting current activities while exploring new opportunities and encouraging both the entry of new actors into the sector and the redeployment of some current actors to opportunities outside it.

2.3.2 The Solution: Support SSFA Capabilities and Diversity Through Inclusive Blue Food Policy

Governments of countries where SSFA operate should place this sector at the center of their national human development and food security strategies, creating initiatives that support the capabilities of the diverse SSFA actors. Supporting the viability of SSFA requires governments to:

-

(a)

Include actors from SSFA in decision-making and policy development

Inclusion of SSFA in decision-making is essential to enable more adaptive governance mechanisms and policies that build on the strengths of the diversity of SSFA, acknowledge the cultural importance and specific roles of blue foods for diverse actors and steer food systems towards a more equitable distribution of blue food benefits.

Women are greatly underrepresented in policy and decision-making, even though they make up half of the workforce in SSFA globally. Recent efforts to improve gender equity in blue food policy have tended to adopt a narrow focus on women, overlooking men or gender relations (Lawless et al. 2021). Such a narrow focus risks exacerbating inequities by placing the blame, or burden for change, on women (Hicks et al. n.d.). Blue food policy development therefore not only needs to involve more input and leadership from women, but also should take a gender transformative approach to improving intersectional equity in SSFA (Hicks et al. n.d.; Lawless et al. 2021; Cole et al. 2020).

Indigenous coastal and riparian Peoples tend to be more blue food-dependent than the wider population in the countries they live in (Bayley 1981; Cisneros-Montemayor et al. 2016). They also have proven systems for food system governance – including knowledge systems – that, if recognized and supported, could enable the ‘decolonization’ of their food systems (Coté 2016). As access to traditional food sources has been lost, adoption of unhealthy diets based on processed foods have led to high rates of diet-related non-communicable diseases (Kuhnlein and Receveur 2003; Hawley and McGarvey 2015). Thus, by supporting Indigenous Peoples’ food (and wider) sovereignty claims, governments could contribute to transformative health benefits in these communities and nations.

Governments should support and strengthen multi-stakeholder initiatives that have the benefits of SSFA at their core, including organizations of fish workers, harvesters and producers at the global, regional, and national levels, such as the World Forum of Fish Harvesters and Fish Workers (WFF), the World Forum of Fisher Peoples (WFFP), and the International Collective in Support of Fish Workers (ICSF).

-

(b)

Expand capabilities through investment in institutions and human capital, and investment in environmental protection and restoration

Securing the future of SSFA requires adaptive action that supports the capabilities of SSFA to deliver both market and non-market societal benefits. Positive environmental outcomes, for example, require engagement of SSFA actors to co-produce knowledge, forge strategies for sustainability and climate adaptation, and participate in and lead environmental restoration, conservation and adaptation efforts.

Governments should create space for SSFA as they expand agricultural and industrial aquaculture and fishery sectors. They should use public and private regulation and financial mechanisms to enable SSFA actors – including Indigenous Peoples – to (re)gain control over the resources, rights, skills and knowledge necessary for environmentally resilient and socially equitable production and trade (including insurance, credit, and market mechanisms to buffer against extreme events).

Governments should also allocate and enforce land, water and labor rights to SSFA through user rights-based systems, the creation of preferential access areas, coastal and inland land use zoning, or other measures. To support the roles of SSFA in creating livelihoods and resilient and equitable food systems, governments should also provide capital, through public and private financial mechanisms that empower, rather than undermine, SSFA actors. In the case of Indigenous Peoples, recognition of their collective sovereign rights is the key starting point.

-

(c)

Support diversification and sustainable intensification

For many SSFA producers, it will be crucial to find pathways for sustainable intensification or expansion of their operations or for diversification into other SSFA products or other sources of livelihood. To that end, governments should invest in R&D and facilitate access to venture capital to support innovation in species/production systems that are of high value for nutrition, livelihoods, and justice. They should also support the development of complementary livelihoods, which are often critical to continued participation by SSFA actors, their control of the resource base and its sustainability.

Costs, trade-offs, and potential environmental and social impacts of intensification and diversification should be carefully considered, and diversification should be proactively designed and monitored. To this end, efforts should be made towards better integration of different data types and sources and enabling the effective and timely access to and use of data by relevant actors. Investment is needed in monitoring systems for catch, effort, production and consumption, and in national surveys of engagement in SSFA that are fully gender-inclusive, and that reflect intersections of gender, age and ethnicity. Promotion of R&D towards technological solutions to data collection, storage and communication/accessibility barriers would effectively support these needs.

-

(d)

Secure economic and nutritional benefits through trade policies and the development and protection of local and national markets

Governments, in particular, those in low-income food insecure nations, need to be able to regulate the activities of large corporate actors and trade to protect the rights (e.g., labor rights, human rights, right to food) of SSFA workers, to ensure that terms, conditions, and revenues from trade are transparent and fair, do not impact local food security, and, where needed, retain high nutritional value products for local consumption. Regulation should consider the potential trade-offs and linkages between nutritional and economic value of resources. It should establish transparent processes, monitoring systems, and accountability mechanisms to ensure the traceability and visibility of social impacts. Market-based approaches that encourage actors to add value to products through processing, marketing or certification need to carefully consider trade-offs in economic, social, environmental, and public health outcomes (see Sect. 2.1).

Governments should also explore opportunities to support “alternative” systems based on short supply chains for products with strong local identities and local, decentralized production and processing. Diversity, deeply embedded in these food systems, could be supported by policies mandating or incentivizing local retention of SSFA products to ensure food self-sufficiency, for example, the development or control of local markets and school feeding programs.

3 Conclusion

Blue foods have vital roles to play in the transformation of the global food system. In the face of growing challenges and rising demand, governments must act now to support and expand these roles. They should bring blue foods into the heart of their food decision-making, by creating a Ministry of Food or other governance structures that integrate blue foods fully into food policies, budgets and programs, managing the terrestrial and aquatic food systems as a whole. They should recognize the right to food and harness the nutritional diversity of blue foods in ways that ensure the equitable distribution of blue food production and consumption. And they should empower and support the millions of small-scale actors in fisheries and aquaculture who produce, process, distribute and trade most of the food we eat, and can be the key to a vibrant, sustainable, healthy, and equitable blue food economy. Recognizing and acting upon the potential role of blue foods in all dimensions of food policy would be a clear win for the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit and achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

References

Anderson CM et al (2018) How commercial fishing effort is managed. Fish Fish 20:268–285

Azam-Ali S et al (2021) Marginal areas and indigenous people: priorities for research and action

Bank MS, Metian M, Swarzenski PW (2020) Defining seafood safety in the Anthropocene. Environ Sci Technol 54:8506–8508

Bayley PB (1981) Fish yield from the Amazon in Brazil: comparison with African River yields and management possibilities. Trans Am Fish Soc 110:351–359

Belton B, Bush SR, Little DC (2018) Not just for the wealthy: rethinking farmed fish consumption in the Global South. Glob Food Sec 16:85–92

Béné C (2020) Resilience of local food systems and links to food security - a review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Secur 1–18

Béné C, Lawton R, Allison EH (2010) “Trade matters in the fight against poverty”: narratives, perceptions, and (lack of) evidence in the case of fish trade in Africa. World Dev 38:933–954

Bennett A et al (2018) Contribution of fisheries to food and nutrition security: current knowledge, policy, and research

Bennett NJ et al (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic, small-scale fisheries and coastal fishing communities. Coast Manage:1–11

Bennett A et al (2021) Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01451-4

Bernhardt JR, O’Connor MI (2021) Aquatic biodiversity enhances multiple nutritional benefits to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118

Bogard JR et al (2015) Inclusion of small indigenous fish improves nutritional quality during the first 1000 days. Food Nutr Bull 36:276–289

Bogard JR et al (2017) Higher fish but lower micronutrient intakes: temporal changes in fish consumption from capture fisheries and aquaculture in Bangladesh. PLoS One 12:e0175098

Campbell SJ et al (2021) Immediate impact of COVID-19 across tropical small-scale fishing communities. Ocean Coast Manag 200:105485

Cinner JE et al (2018) Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nat Clim Chang 8:117–123

Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Pauly D, Weatherdon LV, Ota Y (2016) A global estimate of seafood consumption by coastal indigenous peoples. PLoS One 11:e0166681

Cohen P et al (2019) Securing a just space for small-scale fisheries in the blue economy. Front Mar Sci 6:171

Cole SM et al (2020) Gender accommodative versus transformative approaches: a comparative assessment within a post-harvest fish loss reduction intervention. Gend Technol Dev 24:48–65

Coté C (2016) “Indigenizing” food sovereignty. Revitalizing indigenous food practices and ecological Knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanit Rep 5:57

de Oliveira Estevo M et al (2021) Immediate social and economic impacts of a major oil spill on Brazilian coastal fishing communities. Mar Pollut Bull 164:111984

Dried small fish powder provides opportunity for child health in Myanmar (2020) WorldFish Blog. http://blog.worldfishcenter.org/2020/11/dried-small-fish-powder-provides-opportunity-for-child-health-in-myanmar/

Fakhri M (2020) The right to food in the context of international trade law and policy. https://undocs.org/A/75/219

FAO (2012) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2012. http://www.fao.org/3/i2727e/i2727e.pdf

FAO (2018) Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture: synthesis of current knowledge, adaptation and mitigation options. vol 627

FAO (2020a) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en

FAO (2020b) FAO Yearbook. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2018/FAO annuaire. Statistiques des pêches et de l’aquaculture 2018/FAO anuario. Estadísticas de pesca y acuicultura 2018. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb1213t

Farmery AK et al (2021) Blind spots in visions of a “blue economy” could undermine the ocean’s contribution to eliminating hunger and malnutrition. One Earth 4:28–38

Garrido Gamarro E, Ryder J, Elvevoll EO, Olsen RL (2020) Microplastics in fish and shellfish – a threat to seafood safety? J Aquat Food Prod Technol 29:417–425

Gattuso J-P et al (2018) Ocean solutions to address climate change and its effects on marine ecosystems. Front Mar Sci 5:337

Gelcich S, Reyes-Mendy F, Arriagada R, Castillo B (2018) Assessing the implementation of marine ecosystem based management into national policies: insights from agenda setting and policy responses. Mar Policy 92:40–47

Gephart JA, Pace ML (2015) Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environ Res Lett 10:125014

Gephart JA et al (2021a) Environmental performance of blue foods. Nature 597:360–365

Gephart JA et al (2021b) Scenarios for global aquaculture and its role in human nutrition. Rev fish sci aquac 29:122–138

Golden CD et al (2016) Nutrition: fall in fish catch threatens human health. Nature 534:317–320

Golden CD et al (2021) Aquatic foods to nourish nations. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03917-1

Gordon A, Finegold C, Crissman CC, Pulis A (2013) Fish production, consumption, and trade in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review analysis. https://digitalarchive.worldfishcenter.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12348/884/WF-3692.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hawley NL, McGarvey ST (2015) Obesity and diabetes in Pacific Islanders: the current burden and the need for urgent action. Curr Diab Rep 15:29

Henriksson PJG et al (2018) Unpacking factors influencing antimicrobial use in global aquaculture and their implication for management: a review from a systems perspective. Sustain Sci 13:1105–1120

Hernandez R et al (2018) The “quiet revolution” in the aquaculture value chain in Bangladesh. Aquaculture 493:456–468

Hicks CC et al (2019) Harnessing global fisheries to tackle micronutrient deficiencies. Nature 574:95–98

Hicks CC et al (n.d.) Towards justice in blue food systems. Nat Food

Hilborn R et al (2020) Effective fisheries management instrumental in improving fish stock status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:2218–2224

HLPE (2014) Sustainable fisheries and aquaculture for food security and nutrition. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3844e.pdf

HLPE (2020) Impacts of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition: developing effective policy responses to address the hunger and malnutrition pandemic. http://www.fao.org/3/cb1000en/cb1000en.pdf, https://doi.org/10.4060/cb1000en

Hoegh-Guldberg O et al (2019) The ocean as a solution to climate change: five opportunities for action. http://oceanpanel.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/HLP_Report_Ocean_Solution_Climate_Change_final.pdf

Isaacs M (2016) The humble sardine (small pelagics): fish as food or fodder. Agric Food Security 5:27

Johnson DS (2006) Category, narrative, and value in the governance of small-scale fisheries. Mar Policy 30:747–756

Kaminski AM et al (2020) Fish losses for whom? A gendered assessment of post-harvest losses in the Barotse floodplain fishery, Zambia. Sustain Sci Pract Policy 12:10091

Kawarazuka N, Béné C (2011) The potential role of small fish species in improving micronutrient deficiencies in developing countries: building evidence. Public Health Nutr 14:1927–1938

Koehn JZ et al (2021) Fishing for health: do the world’s national policies for fisheries and aquaculture align with those for nutrition? Fish Fish. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12603

Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O (2003) Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.002221

Lawless S, Cohen PJ, Mangubhai S, Kleiber D, Morrison TH (2021) Gender equality is diluted in commitments made to small-scale fisheries. World Dev 140:105348

Love DC et al (2021) Emerging COVID-19 impacts, responses, and lessons for building resilience in the seafood system. Glob Food Sec 28:100494

McDonald J, Torrens SM (2020) Governing Pacific fisheries under climate change. In: Research handbook on climate change, oceans and coasts. Edward Elgar Publishing

Melnychuk MC et al (2021) Identifying management actions that promote sustainable fisheries. Nat Sustain:1–10

Monnier L et al (2020) Small-scale fisheries in a warming world: exploring adaptation to climate change

Naylor RL et al (2021a) A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 591:551–563

Naylor RL et al (2021b) Blue food demand across geographic and temporal scales. Nat Commun 12:5413

Niane B et al (2015) Human exposure to mercury in artisanal small-scale gold mining areas of Kedougou region, Senegal, as a function of occupational activity and fish consumption. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 22:7101–7111

Oremus KL et al (2020) Governance challenges for tropical nations losing fish species due to climate change. Nat Sustain 3:277–280

Pauly D, Zeller D (2016) Catch reconstructions reveal that global marine fisheries catches are higher than reported and declining. Nat Commun 7:10244

Ratner BD, Åsgård B, Allison EH (2014) Fishing for justice: human rights, development, and fisheries sector reform. Glob Environ Change 27:120–130

Ryckman T, Beal T, Nordhagen S, Chimanya K, Matji J (2021a) Affordability of nutritious foods for complementary feeding in eastern and southern Africa. Nutr Rev 79:35–51

Ryckman T, Beal T, Nordhagen S, Murira Z, Torlesse H (2021b) Affordability of nutritious foods for complementary feeding in South Asia. Nutr Rev 79:52–68

Short RE et al (2021) Harnessing the diversity of small-scale actors is key to the future of aquatic food systems. Nat Food 2:733–741

Siddhnath et al (2020) Dry fish and its contribution towards food and nutritional security. Food Rev Int:1–29

Song AM et al (2020) Collateral damage? Small-scale fisheries in the global fight against IUU fishing. Fish Fish 21:831–843

Starling P, Charlton K, McMahon AT, Lucas C (2015) Fish intake during pregnancy and foetal neurodevelopment--a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrients 7:2001–2014

Sumaila UR, Bellmann C, Tipping A (2016) Fishing for the future: an overview of challenges and opportunities. Mar Policy 69:173–180

Thilsted SH et al (2016) Sustaining healthy diets: the role of capture fisheries and aquaculture for improving nutrition in the post-2015 era. Food Policy 61:126–131

Tigchelaar M et al (2021) Compound climate risks threaten aquatic food system benefits. Nat Food 2:673–682

Troell M et al (2014) Does aquaculture add resilience to the global food system? Proc Natl Acad Sci 111:13257–13263

Turner R, McConney P, Monnereau I (2020) Climate change adaptation and extreme weather in the small-scale fisheries of Dominica. Coast Manage 48:436–455

Udo IU, Okoko AC (2014) Seafood processing and safety: a veritable tool for transformation and empowerment of rural women in Nigeria. Nigerian J Agric Food Environ 10:8–17

Whitney C et al (2020) “Like the plains people losing the buffalo”: perceptions of climate change impacts, fisheries management, and adaptation actions by indigenous peoples in coastal British Columbia, Canada. Ecol Soc 25:33

Acknowledgments

This chapter was prepared by researchers who are part of the Blue Food Assessment (BFA; https://www.bluefood.earth/), a comprehensive examination of the role of aquatic foods in building healthy, sustainable, and equitable food systems. The key messages and recommendations in this chapter were derived from several papers that are part of the BFA, as well as related materials. A complete list of BFA papers can be found at https://www.bluefood.earth/science/.

Funding: the BFA was supported by the Builders Initiative, the MAVA Foundation, the Oak Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leape, J. et al. (2023). The Vital Roles of Blue Foods in the Global Food System. In: von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L.O., Hassan, M.H.A. (eds) Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_21

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_21

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15702-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15703-5

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)