Abstract

This chapter is concerned with identifying: (i) challenges to food systems in Africa, Asia, and Latin America caused by urban development, (ii) how existing food systems respond to these challenges, and (iii) what can be done to improve their responsiveness. The chapter is based on the authors’ published research complemented by additional literature. We define ‘urban food systems’ as food systems linked to cities by material and human flows. Urbanisation poses challenges related to food and nutritional security with the co-existence of multiple forms of malnutrition (especially for women and children/adolescents), changing employment (including for women), and environmental protection. It is widely acknowledged that contemporary food systems respond differently to these challenges according to their traditional (small-scale, subsistence, informal) versus modern (large-scale, value-oriented, formal) characteristics. We go beyond this classification and propose six types of urban food system: subsistence, short relational, long relational, value-oriented small and medium enterprise (SME)-driven, value-oriented supermarket-driven, and digital. These correspond to different consumer food environments in terms of subsistence versus market orientation, access through retail markets, shops or supermarkets, diversity of food, prices and food quality attributes. Urban food supply chains differ not only in scale and technology, but also in the origin (rural, urban or imports) and perishability of food products. We stress the complementarity between short chains that supply many perishable and fresh food items (usually nutrient-dense) and long chains that involve collectors, wholesalers, retailers, storage and processing enterprises for many calorie-rich staple food commodities. More and more SMEs are upgrading their business through technologies, consumer orientation, and stakeholder coordination patterns, including food clusters and alliances.

Urban food systems based on micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) have proven resilient in times of crisis (including in the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic). Rather than promoting the linear development of so-called ‘traditional’ towards ‘modern’ food systems, we propose seven sets of recommendations aimed at further upgrading MSME business, improving the affordability and accessibility of food to ensure food and nutritional security while accounting for the specificities of urban contexts of low- and middle-income countries.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Objective and Focus of the Chapter

This chapter is concerned with identifying: (i) challenges to food systems in Africa, Asia, and Latin America caused by urban development, (ii) how existing food systems respond to these challenges, and (iii) what can be recommended to improve their responsiveness. The chapter is based on the authors ‘published research complemented by published literature.

We define ‘urban food systems’ as food systems linked to cities by material and human flows. “A food system gathers all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities related to the production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, and the outputs of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes” (HLPE 2014:29). This definition is close to the definition of food chains, with three major differences. First, it includes food acquisition, diets and consumer behaviour. Second, it considers a diversity of food products, which is crucial for nutrition security, as well as for the sustainability of production systems. Third, it emphasises the key role of food environments, i.e., “the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural context in which consumers engage with the food system to make their decisions about acquiring, preparing and consuming food” (HLPE 2017:28). Often, contradictory objectives are attributed to food systems, gathered under the general objective of achieving sustainability (Béné et al. 2019). According to FAO (2018:1), a sustainable food system (SFS) delivers food security and nutrition for all in such a way that the economic, social and environmental bases for generating food security and nutrition for future generations are not compromised. Among SFSs, inclusive food systems are defined by Fan and Swinnen (2020:9) as “reaching, benefiting, and empowering all people, especially socially and economically disadvantaged individuals and groups in society.”

2 Challenges Posed by Urban Development

2.1 Urban Growth

The world is becoming increasingly urbanised. Half of the world’s population now lives in cities, 40% in Africa, 49% in South-East Asia, and 81% in Latin America. By 2050, these figures are expected to increase by a further 25%. Cities differ considerably in size, and a high proportion of urban growth is taking place in secondary cities, especially in sub-Saharan Africa where, in 2015, half the population lived in cities of less than 500,000 inhabitants (OECD/SWAC 2020). Compared to the rural population, urban populations have more diverse cultural, economic, and social profiles. A middle class is emerging, defined as an individual’s income ranging from 12 to 50 US$ per capita/day in Africa, accounting for 13% of the population (Neveu-Tafforeau 2017). In sub-Saharan Africa, income growth, which benefits urban areas, started in 2000, but it has faltered since 2013 (Tschirley et al. 2020 based on World Bank data). In Latin America, 40-50% of the population of most countries live in a small number of large cities with more than one million inhabitants. Urbanisation is positively correlated with income per capita, but Latin America is the continent with the highest income inequality, which also persists in urban areas (BBVA Research 2017; OECD 2019). As a region, Asia has modest levels of urbanisation, but is home to half of the world’s urban community, and is the continent with the fastest urban growth (Leeson 2018).

2.2 Challenges for Urban Food Systems

Urbanisation poses several policy challenges for urban food systems. These are related to food and nutritional security, employment, and environmental protection.

2.2.1 Urban Food and Nutritional Security

In contrast to rural areas, most people who live in cities do not produce food and must rely on local markets. Food purchased in markets represents more than 80% of food consumption in cities in sub-Saharan Africa, compared with 50% in rural areas (Tschirley et al. 2020). There are many signs that urban food security is inadequately addressed, especially in Africa. “Urban food insecurity in low-income countries, estimated by the Food Insecurity Experience Scale of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, is higher (50%) than levels in rural areas (43%). In urban slums, other studies estimate food insecurity at up to 90%” (Tefft et al. 2017:11–12).

Urban food consumption is characterised by a triple burden of malnutrition, with the persistence of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies – especially related to iron deficiency anaemia in women of reproductive age and young children - and the increasing prevalence of overweight/obesity (GNR 2020). With rising incomes, urban residents are eating more animal-source foods and processed foods that may be low in micronutrients, while high in calories and fat (Popkin et al. 2012; Yaya et al. 2018; Holdsworth et al. 2020; Rousham et al. 2020). These poor quality diets affect children of all ages from infancy to adolescence, and food systems do not currently account sufficiently for the nutritional needs of children and adolescents (UNICEF/GAIN 2018). Nutritional problems are amplified by excessively monotonous diets and limited consumption of fruit, vegetables, and pulses, as well as lack of physical activity (Popkin et al. 2012). Likewise, the consumption of imported food by urban dwellers is increasing – although the proportion is still limited: only 5% in Africa, mostly imported cereals, according to Bricas et al. (2016) and Tschirley et al. (2014); and consumers commonly combine local and imported products in meals, resulting in a hybridisation of cooking (Soula et al. 2020). In Latin American cities, food security improved for many years, partly as result of “zero hunger” strategies first developed in Brazil in the late-1990s and later in other countries in the region. However, in recent years, food insecurity has started to rise again as the result of increased social inequality and due to the Covid-19 pandemic. At the same time, Latin America is facing escalating obesity rates, which affect 24% of the regional – mostly urban – population, almost double the global level of 13.2%, which is explained by unhealthy diets and poverty (FAO, RUAF 2019).

In parallel, food safety has become a major public health issue. Food safety crises are regularly reported in the media, especially in South-East Asia, where consumers’ fears are linked to chemical products in fruit and vegetables and antibiotic residues in meat (Figuié et al. 2004; Ortega and Tschirley 2017). This is due to new industrial and domestic sources of pollution close to agricultural production areas, and the increase in the use of chemical inputs by farmers (De Bon et al. 2010; Reynolds et al. 2015). The lengthening of food supply chains and the lack of knowledge about hygiene also creates risks of contamination in the processing, marketing, handling and consumption stages (Jaffee et al. 2018). Consumer concerns about food safety have potential nutritional consequences, as they may reduce the consumption of fruit and vegetables because of concerns about pesticides, or push consumers towards packaged (often highly processed) foods because they are perceived as safer.

2.2.2 Food Convenience

Another growing consumer pattern is related to the convenience of where they buy and what they buy. As women are increasingly employed outside their homes and lifestyles become more sedentary, demand is growing for packed, pre-prepared food that can be purchased near offices or shops where it is easy to park (for the middle classes) (Reardon et al. 2019). In sub-Saharan Africa, processed food accounts for between 60% (in West Africa) and 70% (in eastern and southern Africa) of total food consumption, compared to, respectively, 50% and 30% in rural areas. Food consumption outside the home is on the increase. The proportion varies across African cities, ranging from 6% in Freetown and Conakry to 25% in cities of Nigeria and Tanzania, and 30% in Cotonou, Lomé and Abidjan (Tschirley et al. 2020). Street food is especially convenient for urban workers and low-income households who may not have the resources and facilities to purchase raw ingredients and prepare dishes at home, especially in slums (Soula et al. 2020; Pradeilles et al. 2021). In Latin America, between 2000 and 2013, the consumption of ultra-processed products increased by more than 25%, and fast food consumption by almost 40% (PAHO 2015).

2.2.3 Urban Employment

Cities in the Global South are characterised by the absence of stable employment, and poverty is increasingly becoming an urban phenomenon (Ravaillon 2016). The difference in living standards among the urban population is widening, thereby increasing social inequalities. The informal sector still provides most employment (especially for women), accounting for up to 90% in low-income countries (LICs) and 67% in emerging countries (Bonnet et al. 2019). Sub-Saharan Africa is facing premature deindustrialisation, with only 11% of employment in the manufacturing sector, mostly in the food industry (Giordano et al. 2019 based on Rodrik 2016 and ILO 2018). In Latin America, 60% of mostly urban people are employed in the informal sector.

2.2.4 Quality of the Urban Environment

Last, but not least, the urban environment is responsible for major air, water and soil pollution (Amegah and Agyei-Mensah 2017; Adimalla 2020), severe risks of flooding (Douglas 2017; Pervin et al. 2020), and problematic waste disposal, as the balance between what enters and leaves the city is largely negative (Guerrero et al. 2013). This jeopardises the production of safe food in cities. At the same time, if handled safely, agriculture can recycle part of the waste produced (De Bon et al. 2010).

Cities can be viewed as concentrations of people and biomass that produce particular forms of economic and environmental stress (Chaboud et al. 2013). Yet, cities also concentrate knowledge, as people from different backgrounds mix, including rural and international migrants, and public and private investments provide a favourable substrate for innovation (Cobbinah et al. 2015).

The challenges faced by urban development and new consumer expectations lead to questions about the capacity of existing urban food systems to adapt. This is detailed in the following section.

3 The Characteristics of Urban Food Systems in the Global South

3.1 Spatial and Relational Organisation

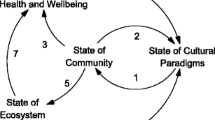

The organisation of urban food systems in Africa, Asia, and Latin America is summarised in Fig. 1. We review the characteristics of the chains that supply food to urban consumers, their relations with urban food environments, and urban consumer profiles. The nature of urban food environments, especially food retailing landscapes, as well as consumer living standards, in addition to the perishability and origin of food, results in major differences among food supply chains.

The characteristics of urban food systems in the Global South. (Source: Adapted from HLPE (2017) and David-Benz et al. forthcoming)

Food chains and food systems in LICs are currently classified differently depending on their operation and organisation, which is related to the evaluation of their outcomes, impacts and performance. This type of classification relates to the market orientation, the scale of activities, informal versus formal (i.e., whether the business is registered or not), added value in the chain through the adoption of technologies and orientation towards consumer expectations, in particular regarding visual, organoleptic, and sanitary quality. The High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE 2017) report distinguishes traditional food systems, which are dominant in rural areas and involve open-air markets and small shops with limited concern for food quality or diversity, and modern food systems, which emerge in urban areas and are driven by the development of supermarkets and increased income, as well as an intermediary type termed mixed food systems. As the HLPE typology mostly considers differences between rural and urban settings, and as urban food supply chains are diverse, the rest of the chapter highlights the determinants of variable organisation and performance of urban food systems and leads us to propose six types.

Even though subsistence agriculture is of minor importance in terms of total urban food consumption, in cities in the Global South, it can play an important role in the livelihoods and social inclusion of some vulnerable inhabitants, as proven in Tamale and Ouagadougou (Bellwood-Howard et al. 2018), Cape Town (Olivier and Heinecken 2017), Hanoi (Pulliat 2015), Quito and Rosario (Renting and Dubbeling 2013). Urban gardens also have important pedagogical functions, e.g., through schooling programmes or community gardens (Hou 2017). The multi-functionality of urban agriculture means that it is a ‘cheap’ producer of public goods.

We now turn to market-oriented urban food systems. Urban consumers are mainly supplied by small-scale market vendors and neighbourhood shops, even though supermarkets and convenience stores are increasing their market share. Supermarket distribution is still limited for food, especially in Africa and South-East Asia: less than 10% of purchases in Côte d’Ivoire (Neveu-Tafforeau 2017), Kenya and Uganda (Wanyama et al. 2019), and less than 20% in Vietnam (University of Adelaide 2014) – the percentages being even lower for fresh food, all of which may be explained by low consumer purchasing power, as well as by consumer preference for traditional retail formats. So-called traditional urban food systems predominate in the urban context of LICs. There is overlap between what is termed traditional or informal markets/sectors/systems, both terms referring to the small scale of production, the absence of registration and public support. Traditional systems are often described as ‘poor-friendly,’ as suppliers are mostly concerned with subsistence incomes (Vorley 2013). Moreover, they are an important part of the social fabric of low-income urban communities, as seen in studies in Ghana and Kenya (Pradeilles et al. 2021). Food processing, food distribution, and food catering are major sources of urban employment, especially for the vulnerable poor (particularly women) who lack qualifications and social and economic capital (Allen et al. 2018). The urban food catering sector is varied, ranging from school canteens to street caterers and restaurants targeting different types of customers. Most processing takes place in MSMEs at an artisanal scale (Tschirley et al. 2020) in various locations within and outside cities. While street vendors are documented as major providers of food and livelihoods for poor urban residents, especially women, in Africa and Asia, they usually lack public support (Turner and Schoenberger 2011; Ogunkola et al. 2021).

Traditional food systems are sometimes judged to be inefficient in responding to new consumer expectations, especially concerning quality and convenience (Reardon et al. 2019). Low investments in infrastructure may limit the regular supply and availability of some nutrient-dense foods like fruit and vegetables (Maestre et al. 2017). Regarding the effect of traditional food systems on waste reduction, some studies report evidence for inefficiency related to poor logistics, while others argue that less stringent quality criteria help reduce waste.

In addition to scales and technology, another major factor that influences the organisation of food chains is food perishability, as it influences the location of production and the length of food chains, especially when logistics are limited, which is even worse in times of crisis, like the current Covid-19 pandemic. The location of production and the possibility of producing locally depend on the climate and the soil, as well as on the history of specialisation in some territories. Mapping food supply chains is crucial for representing differences in the length of chains, in the number of intermediaries and in their origin. This is the basis of approaches such as foodsheds, city-region food systems and short versus long chains (Blay-Palmer et al. 2018; Schreiber et al. 2021). Short versus long chains refers to physical as well as relational factors, and the two are linked. Short chains (in terms of distance and relations) have fewer intermediaries than long ones. This may lead to lower final prices than longer chains, but this is not systematically the case, because long chains may enable economies of scale (De Cara et al. 2017). In line with predictions from spatial economics, short food chains predominate in the supply of perishable produce, e.g., leafy vegetables, milk, eggs and chicken. These commodities are nutrient-dense and commonly under-consumed relative to nutritional recommendations. The farmers themselves, or their relatives, are frequently involved in wholesale and/or retail distribution. On the other hand, staple food crops, including cereals, tubers, pulses, vegetables that can be stored, e.g., onions, and some animal products, are supplied by long chains originating in local rural areas or by imports (Moustier 2017a, b; Karg et al. 2019; Lemeilleur et al. 2019). They often involve a chain of rural collectors, rural wholesalers, urban wholesalers, and urban retailers who supply all types of urban consumers. Transactions take place in wholesale and retail markets located so as to minimise traders’ and consumers’ transport costs (Blekking et al. 2017; Lemeilleur et al. 2019). With the development of transport, credit, and mobile phones, these chains may be shortened, and the roles of rural collectors and wholesalers may be reduced. This transformation is termed the ‘quiet revolution’ in agrifood value chains in low- and middle-income countries by Reardon (2015).

Another important aspect of chain organisation concerns business-to-business relationships. Food chains in LICs are characterised by long-term acquaintanceship and reciprocity, together with competition among hundreds of vendors, resulting in a certain degree of price homogeneity, even though oligopolies of wholesalers are observed because of limited access to credit and storage facilities (Fafchamps 2004).

Modern distribution systems, driven by supermarkets, are characterised by labour-saving and capital-intensive technologies in terms of logistics, refrigeration, self-service, packaging, and cash registers, in addition to the recourse to contractual arrangements with dedicated wholesalers (Hagen 2002). They are judged to be efficient in terms of logistics and quality (Reardon et al. 2019), but with potential negative effects on nutrition, because they supply a wide range of highly processed foods rich in fats and sugar (Demmler et al. 2018; Giordano et al. 2019; Wertheim-Heck and Raneri 2019). Regarding affordability for the poor, modern systems are usually presented as less poor-friendly because of higher prices and transport constraints. Modern systems also create less employment per unit of product (Moustier et al. 2009; Wertheim-Heck and Raneri 2019). Regarding differences in prices between supermarkets and traditional vendors, when controlling for quality differences, results are country-specific. When supermarkets gain a substantial market share, they can reduce their logistic costs and provide food at lower prices, especially food that can be stored (Reardon et al. 2010; Nuthalapati et al. 2020). Prior to that stage, food is usually cheaper and more accessible in open markets and small shops than in supermarkets (Moustier et al. 2009; Wanyama et al. 2019). Moreover, supermarkets favour the use of plastics for wrapping fresh food, which is a major environmental concern (Letcher 2020).

3.2 Innovations in Urban Food Systems

Considering the ability of urban food systems to adapt to new consumer demand for quality and convenience, we need to look beyond the traditional approach that qualifies modern or supermarket-driven chains as innovative and traditional chains as obsolete and lacking dynamics. A number of MSMEs are indeed increasingly upgrading their technologies and improving product quality in response to new consumer expectations. At the same time, they create new chain organisation patterns with increased chain interactions and different forms of vertical integration, with the general support of national and international public programmes (Moustier and Renting 2015; De Brauw et al. 2019; Tefft et al. 2017). This is the case with farmer organisations that sell food in shops or at farmers’ markets in Laos, India, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, and Kenya, or by subscription in Dakar and in some South African cities (Freidberg and Goldstein 2011; Joshi et al. 2012; Renting and Dubbeling 2013). Entrepreneurial producers, e.g., le Terroir in Abidjan, can sell dairy products and cold cuts to wealthy urban consumers thanks to processing and cold storage (Neveu-Tafforeau 2017). Caterers, private companies, restaurants, and school canteens are developing strategies to ensure food safety and promote local products by signing contracts with local producer groups. This is also the case for public programmes targeting the urban poor, e.g., the food purchase programme in Brazil (Berchin et al. 2019). Food caterers and processing SMEs also innovate to supply processed local food to urban dwellers (Ferré et al. 2018; Reardon et al. 2021a). Yet, these initiatives are still precarious because of the cost of access to sales points for farmers, low levels of state support, lack of product diversity, and lack of guaranteed food safety.

Supermarket chains are expanding rapidly in countries where incomes are rising, as in South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, and China. Supermarkets carry both local and international brands and are developing strategies for quality control and guaranteed origin, including using dedicated wholesalers and contracts, but still face difficulties concerning quality control and traceability. Supermarket chains are usually supported by city and national governments on the grounds of modernity and hygiene, but face increasing competition from traditional markets and from companies that use digital technology for logistics and delivery to consumers (Neveu-Tafforeau 2017 with reference to Côte d’Ivoire and Si et al. 2019 with reference to China). Overall, supermarkets vary in their supply strategies, including whether they favour linkages with local food chains, in their pricing and in the payment conditions offered to local farmers, as well as in the training and logistics they may provide to farmers (Minten et al. 2017).

Digital technology can be used by MSMEs, as well as by supermarkets or by new large-scale capital-intensive companies, which sometimes partner with SMEs for their supply, logistics, or final delivery (Reardon et al. 2021a; Tefft et al. 2017; Si et al. 2019). E-commerce has been spurred by sanitary crises, including SARS and Covid-19, and is developing particularly rapidly in Asian countries, including China, India and Vietnam (Reardon et al. 2021b; Vietnam news 2021; Dao 2020).

3.3 Six Types of Urban Food System

To summarise, we advocate going beyond the simplistic classification of traditional versus mixed and modern food systems. This classification may stigmatise the small-scale relational food systems that are competitive in terms of food availability, accessibility, and affordability. Moreover, it suggests a linear trend of change from one system to another, while the reality frequently turns out to be combinations and synergies between different patterns. Hence, based on our review of the literature, we propose the following typology – while acknowledging that overlaps between and combinations of types are possible. The main characteristics of each type are summarised in Table 1.

4 Adaptation to Demand and Crises in Urban Food Systems

The capacity of food systems in low- and middle-income countries to supply urban populations in sufficient quality and quantity is often questioned. The development of agribusiness at all stages of food chains is sometimes seen as one way to overcome these shortcomings. Large-scale private investments in mechanised production, processing, storage, and retailing are put to the fore. Yet, innovations are not neutral in terms of social inclusion. It is sometimes even claimed that the present problems of food security, including unhealthy food, are caused by innovations and agribusinesses (Glover and Poole 2019). Labour-saving and scale-biased innovations have a negative impact on employment for the poor and they are less suitable in regions where labour is in excess supply than is the case with capital-saving or neutral innovations (unless massive credit programmes targeting the poor are launched). Moreover, they ignore the diversity and creativity that exist at the level of food systems driven by MSMEs, including producer organisations, as explained in Sect. 3.2.

The Covid-19 crisis has caused major disturbances, the most important being the decrease in sources of income among vulnerable urban dwellers, with an impact on women and children, due to restrictions on movement and the disturbances in logistics systems (Shekar et al. 2021). In some countries, the increased vulnerability of the urban poor has been addressed through food aid programmes and increased social safety nets targeting women (Shekar et al. 2021). At the same time, the local food provisioning sector has proven to be quite resilient, with no major breaks in the food supply chains. Public policies restricting the sale of food in open markets have been varied, with mixed consequences for access to employment and to food by the poor. For instance, the municipalities of Abidjan and Dakar found ways to maintain retail sales of food in open markets through regulations concerning hygiene and social distancing, enabling some contactless proximity, which was not the case in Burkina Faso, where markets were shut down at the beginning of the crisis (Dury et al. 2021; IPES Food 2020; Moustier 2020; Devereux et al. 2020).

Considering their inclusiveness and resilience, we recommend supporting urban food transformations based on MSMEs. These are discussed in more detail in the following section.

5 Solutions for Enhancing Inclusive Urban Food System Transformations

In the previous section, we reported insights from the literature on the advantages and shortcomings of current urban food systems. Yet, these insights are quite patchy in terms of time, space, and commodity coverage. That is why our first recommendation concerns the need for better data. Second, we provide recommendations related to urban food planning, mostly concerning the protection of land for agriculture, marketplaces, and shops, as well as regulations pertaining to supermarkets and food safety. These should enable urban consumers to benefit from a variety of food retailing formats. We also recommend communication actions to promote nutrient-dense foods, e.g., fruit, vegetables, nuts and legumes, which may be available to consumers locally, but are not always purchased, because consumers may have little knowledge of their health benefits or of how to include them in their meals and dietary practices. Rural-urban transportation, which is the mandate of national governments, should be a priority to improve both food availability and quality and to reduce food losses. National programmes should also improve access to credit and training on food processing and storage for food MSMEs. Improvements in food quality can be obtained through food processing and storage technologies, which are not always available to MSMEs because they have no access to credit and training programmes. Finally, securing coordination among food system actors is required to enhance the quality and availability of diverse food items. Details of these recommendations are given below. Some recommendations concur with the recent work of the Centre for Food Policy (London University) aimed at identifying policies and actions that can orient food systems towards healthier diets for all (Hawkes et al. 2020).

While some recommendations (Sects. 5.1 and 5.3) relate to all types of urban food system, some are more particularly relevant for some of the urban food system types identified here (see Table 2).

The recommended interventions are intended to upgrade the operation of MSMEs, as well as changing consumers’ environments to enable healthier food, while keeping costs and prices affordable for the urban poor. This is why the proposed interventions are sober in terms of capital and energy; moreover, economies of scale are reached through coordination of SMEs, rather than by providing support to agribusinesses.

5.1 Obtaining Accurate Data on Food Consumption, Foodsheds, and Food Chains

Policymakers need to support inter-disciplinary teams of researchers, including geographers, economists, specialists in consumption and statisticians, to collect accurate and updated data on food consumption, foodsheds and food chains.

Available data on food consumption underestimate two kinds of patterns: food consumed away from the home, and seasonal food, including fruit and vegetables. Adequate and valid methods of measurement are needed to address this deficiency (Rousham et al. 2020). Identifying the specific role of different production areas and market intermediaries in urban food supply requires original sources of data. Comparing what is produced over a year in a city, what is produced in rural areas and what is imported has many limitations, including difficulties in capturing information on perishable seasonal products; additionally, such comparisons do not take the destination of products into consideration. Accurately appraising the role of different production areas and intermediaries in urban food supply requires surveys of wholesale and retail markets, and of the origin and quantities of products traded. Surveys should be conducted at different times of the year to account for seasonal variations, and with specific relational expertise. A foodshed approach (Schreiber et al. 2021) combined with value chain analysis is recommended to identify the production areas of targeted nutrient-dense food and to assess how the organisation of the value chain (geography and intermediation) determines the quality, accessibility and competitiveness of the supply of targeted food products.

5.2 Urban Food Planning for Poor-Friendly Production and Marketing Spaces

5.2.1 Protection of Land for Multifunctional Urban Agriculture

If market forces are left unrestricted, urban agriculture is doomed to disappear, given the forces of pressure on land and water. This is detrimental to urban food security and livelihoods and may create environmental problems. We consequently recommend protecting land for agriculture in areas where it is documented to play a major role in both food supplies and livelihoods, and where pollution is not an issue. Access to land can be secured through regulations (protecting agricultural parks or zoning measures) and formal contracts. How urban planning is enforced needs to be closely monitored, as it has frequently been observed that legal protection of land is regularly trespassed owing to the attraction of private investors’ urban development schemes (De Bon et al. 2010; Valette and Philifert 2014; Dao 2019).

5.2.2 Upgrading Food Marketplaces

Urban marketplaces are frequently characterised by congestion, difficulty moving around, and lack of hygiene. Some past projects aimed to replace urban marketplaces with wholesale markets located outside the city boundaries, but these markets were underused due to limited transport facilities, as well as the high cost of market stalls (Moustier 2017a, b). We thus recommend upgrading existing markets. The priority should be covering them and concreting the ground. Other basic infrastructures and services should be provided, including access to clean water. The planning of new markets should include in-depth consultation of a panel of market users, especially wholesalers and retailers (Hubbard and Onumah 2001). Food markets can also be combined with a “food hub” function, thereby creating new market linkages with food producers in the region, as developed in Colombia (Dubbeling et al. 2017). Market regulations concerning hygiene should be designed with the involvement of representatives of market users. Farmers’ markets should be encouraged by providing adequate space and market services (Baker and de Zeeuw 2015).

5.2.3 Accommodating Space for Mobile Vendors

Given the importance of street vending in the livelihoods of vulnerable urban populations (especially women), we recommend their business should be acknowledged and support provided that aims at “semi-formality” (Cross 2000). Semi-formality refers to a self-regulating system with some light third-party regulatory enforcement, thus protecting the flexibility of street vending, which is uniquely adapted to the conditions of the urban poor. Regulatory enforcement requires consulting a panel of street vendors to protect some urban spaces so as to allow vendors to conduct their temporary business while ensuring their commitment to respecting rules of hygiene and traffic safety. Some examples of successful integration of street vending in urban planning can be found in Loc and Moustier in Vietnam (2016), in Srivastana in India (2012), in Dai et al. in China, (2019), and in Tangworamonycon in Thailand (2014).

5.3 Consumer-Oriented Promotion of Nutrient-Dense Food

Culinary recipes and techniques that enhance the nutritional quality of the food, as well as the packaging and labelling of local nutrient-dense food items, including fruit, vegetables, pulses, and nuts, should be promoted. These food items are recommended to enable urban consumers, including women and children, to diversify their diets in line with nutritional and planetary limits and the promotion of local biodiversity (EAT-Lancet Commission 2019). Different ways to increase public awareness about healthy food and promote traditional food cultures are discussed in Hawkes et al. (2020).

5.4 National Provisioning of Infrastructures and Services for MSMEs

5.4.1 Improving Rural-Urban Transport

Roads between cities and rural areas, which play a major role in supplying food to cities, need to be expanded and maintained, along with alternative transport routes by rail or water (Popoola et al. 2021).

5.4.2 Disseminating Small-Scale Food Processing Technologies

Technological innovations are available to improve the safety and nutritional qualities of food, but not at a sufficient scale for MSMEs (Ferré et al. 2018; Pallet and Sainte-Beuve 2016). Examples of small-scale food storage and processing technologies that reduce food losses, based on a thorough assessment of losses along food chains, are given by Tefft et al. (2017).

5.4.3 Service Provisioning for MSMEs

Innovation in the artisanal sector needs to be supported by providing credit to increase working capital, so as to enable investment in semi-industrial processing. Training on how to improve the quality of food also needs to be made available to MSMEs. This falls under the mandate of the public sector. As public resources are scarce, partnering with the retail sector may be an appropriate solution, if it enables sufficiently wide coverage of both farmers’ and consumer’s economic profiles. The public sector also needs to invest human resources in food quality control, with random checks of food safety and labelling frauds, as well as graduated sanctions for non-compliance, at various points along the chain, including wholesale and retail markets (Hawkes et al. 2020; Dao 2020).

5.5 Fostering Multi-stakeholder Coordination and Governance

Secured forms of coordination between food suppliers and vendors range from agreements on quality or quantity requirements to contractual joint commitments. Innovative producer organisations that include processing and distribution, e.g., “Entreprises de Services et Organisations de Producteurs” (ESOPs), should be encouraged, as this increases the scale of operation and investments in quality while creating added value for farmers (Maertens and Velde 2017). The concept of ‘intermediate food systems’ (systèmes alimentaires du milieu) developed by Chazoule et al. (2018) and tested in some African situations (Sirdey 2020) can be used to model the hybridisation of traditional and modern systems that combine cooperation mechanisms with economies of scale.

Cities can become important actors in the development of SFSs, particularly through their governance of urban agriculture, school canteens, and waste management (Bricas 2019; Fages and Bricas 2017). Through the Milan food policy pact (https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/), city officials are invited to commit to 31 actions aimed at sustainable food provisioning and consumption. In many cities, permanent urban food policy councils have been set up, with interesting outcomes, e.g., school catering programmes (Sonnino et al. 2019). Governing urban food systems in an inclusive way involves setting up multi-stakeholder city-region food platforms. These include public stakeholders working in different sectors (agriculture, trade, environment, health, social care) and at the national and city scales, together with a panel of value chain actors and service support organisations. The stakeholders meet regularly to exchange and discuss information, aiming to reach a consensus on desirable outcomes and on a set of policy recommendations (Blay-Palmer et al. 2018; see also https://ruaf.org/ for many examples of urban food policy platforms, sometimes on the basis of urban agriculture programmes, like in Quito). Food system assessment and dialogues are good starting points (Huynh et al. 2021; David-Benz et al. forthcoming).

In all these platforms, access and use of market information is strategic. Systems favouring interactions among farmers, traders and public agencies, conducive to new marketing decisions for farmers, new supply options for traders, and priorities for extension workers and input suppliers, e.g., for the support of off-season production as a substitute for imports, are termed alliances by the World Bank (2016), as quoted by Tefft et al. (2017), or market information and consultation systems (MICS). Modelling tools and serious games can be combined in such information and consultation systems to present options for local production that better address consumer needs (Verger et al. 2018; Mangnus et al. 2019).

6 Conclusion

In the context of continuous urban development and widening income disparities, urban food systems in countries of the Global South are becoming more market-oriented and innovative, with new investments in logistics and quality. Small-scale, labour-intensive food supply chains with relational governance and decentralised food distribution that provide food at a low price close to consumers’ homes have proven resilient. They are poor-friendly and adapted to the time and work demands of women, in particular compared to agro-industrial schemes. Relative to the vast recent literature on food systems, this chapter highlights some peculiarities of the urban context and food systems of low- and middle-income countries. These include the importance of food caterers and mobile and open market vendors, as well as urban agriculture, in the provisioning of the urban poor; the high pressure on urban agricultural land and water; the innovative nature and consumer orientation of many food MSMEs; and the growing concerns and involvement of urban authorities in urban food security. Opportunities exist to respond to consumer demand and needs in terms of nutritional balance and food safety, while creating employment for less educated urban populations, especially for women. To exploit these opportunities, we have recommended a set of actions representing public support to endogenous patterns, adapted to the six types of urban food system that we brought to the fore, as a variety of food systems is needed to target different objectives and local contexts (Seck 2021).

Notes

- 1.

The lack of data was underlined at the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact meeting in Ouagadougou, February 15-19, 2021.

References

Adimalla N (2020) Heavy metals pollution assessment and its associated human health risk evaluation of urban soils from Indian cities: a review. Environ Geochem Health 42(1):173–190

Allen T, Heinrigs P, Heo I (2018) Agriculture, food and jobs in West Africa. West African Papers, N°14. OECD Publishing, Paris

Amegah AK, Agyei-Mensah S (2017) Urban air pollution in sub-Saharan Africa: time for action. Environ Pollut 220:738–743

Baker L, de Zeeuw H (2015) Urban food policies and programmes. In: de Zeeuw H, Drechsel P (eds) Cities and agriculture: developing resilient urban food systems. Routledge, London, pp 26–55

BBVA Research (2017) Urbanization in Latin America. https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Urbanization-in-Latin-America-BBVA-Research.pdf. Accessed 01 Dec 2021

Béné C, Oosterveer P, Lamotte L, Brouwer ID, de Haan S, Prager SD, Talsma EF, Khoury CK (2019) When food systems meet sustainability. Current narratives and implications for actions. World Dev 113:116–130

Blay-Palmer A, Santini G, Dubbeling M, Renting H, Taguchi M, Giordano T (2018) Validating the City region Food system approach: enacting inclusive, transformational city region Food Systems. Sustainability 10(5):1680

Blekking J, Tuholske C, Evans T (2017) Adaptive governance and market heterogeneity: an institutional analysis of an urban Food system in sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 9:2191

Bellwood-Howard I, Shakya M, Korbeogo G, Schlesinger J (2018) The role of backyard farms in two west African urban landscapes. Landsc Urban Plan 170:34–47

Berchin II, Nunes NA, de Amorim WS, Zimmer GAA, da Silva FR, Fornasari VH, de Andrade JBSO (2019) The contributions of public policies for strengthening family farming and increasing food security: the case of Brazil. Land Use Policy 82:573–584

Bonnet F, Vanek J, Chen M (2019) Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical brief. International Labour Office, Geneva. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Women%20and%20Men%20in%20the%20Informal%20Economy%203rd%20Edition%202018.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 21

Bricas N, Tchamba C, Mouton F (eds) (2016) L’Afrique à la conquête de son marché intérieur. Editions AFD, Paris

Bricas N (2019) Urbanization issues affecting Food system sustainability. In: Brand C, Bricas N, Conare D, Daviron B, Debru J, Michel L, Soulard CT (eds) Designing urban Food policies. Concepts and approaches. Springer, pp 1–25

Chaboud G, Bricas N, Daviron B (2013) Sustainable urban food systems: state of the art and future directions. Communication to the fifth Aesop urban food planning conference. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02745437/document#page=39

Chazoule C, Lafosse G, Brulard N, Crosnier M, Van Dat C, Desole M, Devise O (2018) Produire et échanger dans le cadre de systèmes alimentaires du milieu. Pour 2:143–150

Cobbinah PB, Erdiaw-Kwasie MO, Amoateng P (2015) Africa’s urbanisation: implications for sustainable development. Cities 47:62–72

Cross J (2000) Street vendors, and postmodernity: conflict and compromise in the global economy. Int J Sociol Soc Policy 20(1/2):29–51

De Bon H, Parrot L, Moustier P (2010) Sustainable urban agriculture in developing countries. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 30(1):21–32

Dai N, Zhong T, Scott S (2019) From overt opposition to covert cooperation: governance of street food vending in Nanjing, China. Urban Forum 30(4):499–518

Dao TA (ed) (2020) Developing a sustainable safe food value chain in Vietnam. Vietnamese version. Agricultural-Construction Publishing Houses, Hanoi

Dao TA (ed) (2019) Development of sustainable peri-urban agriculture in Vietnam. Vietnamese version. Agricultural Publishing House

David-Benz H, Sirdey N, Deshons A, Orbell C, Herlant P (forthcoming) Assessing national and subnational food systems. A methodological framework. CIRAD/FAO/EU. Draft version available at: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/food_system_analysis_rapid_methodology-english_18_may_2020.pdf. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

De Cara S, Fournier A, Gaigné C (2017) Local Food, urbanization, and transport-related greenhouse gas emissions. J Reg Sci 57(1):75–108

Demmler KM, Ecker O, Qaim M (2018) Supermarket shopping and nutritional outcomes: a panel data analysis for urban Kenya. World Dev 102:292–303

De Brauw A, Brouwer ID, Snoek H, Vignola R, Melesse MB, Lochetti G, Ruben R (2019) Food system innovations for healthier diets in low and middle-income countries, Working paper 1816. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington

Devereux S, Béné C, Hoddinott J (2020) Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Security 12(4):769–772

Douglas I (2017) Flooding in African cities, scales of causes, teleconnections, risks, vulnerability and impacts. Int J Disaster Risk Reduction 26:34–42

Dubbeling M, Santini G, Renting H, Taguchi M, Lançon L, Zuluaga J, De Paoli L, Rodriguez A, Andino V (2017) Assessing and planning Sustainable City region Food systems: insights from two Latin American cities. Sustainability 9:1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081455

Dury S, Alpha A, Zakhia N, Giordano T (2021) Les systèmes alimentaires aux défis de la crise de la Covid-19 en Afrique: enseignements et incertitudes. Cahiers Agric 30(12)

Fafchamps M (2004) Market institutions in sub-saharan Africa. Theory and evidence. The MIT Press, Cambridge

EAT-Lancet Commission (2019) Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet Commissions. https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/EAT. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

Fages R, Bricas N (2017) Food for cities. What roles for local governments in the global South? Paris, AFD, [Full Text]

FAO (2018) Sustainable food systems: concept and framework. http://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/fr/c/1160811/. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

FAO, RUAF (2019) Evaluación y planificación del Sistema Agroalimentario Ciudad-Región. Medellin, Roma. http://www.fao.org/3/ca5747es/ca5747es.pdf. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

Ferré T, Medah I, Cruz JF, Dabat MH, Le Gal PY, Chtioui M, Devaux-Spatarakis A (2018) Innover dans le secteur de la transformation agroalimentaire en Afrique de l’Ouest. Cahiers Agric 27(1):15011

Figuié M, Bricas N, Than VPN, Truyen ND (2004) Hanoi consumers’ point of view regarding food safety risks: an approach in terms of social representation. Vietnam Soc Sci 3(101):63–72

Freidberg S, Goldstein L (2011) Alternative food in the global south: reflections on a direct marketing initiative in Kenya. J Rural Stud 27(1):24–34

Giordano T, Losch B, Sourisseau JM, Girard P (2019) Risks of mass unemployment and worsening of working conditions. In: Dury S. et al (Eds), op.cit., 75–78

Glover D, Poole N (2019) Principles of innovation to build nutrition-sensitive food systems in South Asia. Food Policy 82:63–73

Guerrero LA, Maas G, Hogland W (2013) Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Manag 33(1):220–232

Hagen JM (2002) Causes and consequences of food retailing innovation in developing countries: supermarkets in Vietnam, Working Paper, Cornell University, Department of Applied Economics and Management. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/127310/

Hawkes C, Walton S, Haddad L, Fanzo J (2020) 42 policies and actions to orient food systems towards healthier diets for all. Centre for Food Policy, City, University of London, London

HLPE (2014) Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems. HLPE report nr 8. http://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/fr/c/854257/

HLPE (2017) Nutrition and food systems HLPE report nr 12. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/hlpe/hlpe_documents/HLPE_Reports/HLPE-Report-12_FR.pdf

Holdsworth M, Pradeilles R, Tandoh A, Green M, Wanjohi M, Zotor F, Laar A (2020) Unhealthy eating practices of city-dwelling Africans in deprived neighbourhoods: evidence for policy action from Ghana and Kenya. Glob Food Sec 26:100452

Hou J (2017) Urban community gardens as multimodal social spaces. In: Tan P, Jim C (eds) Greening cities. Advances in 21st century human settlements. Springer, Singapore

Hubbard M, Onumah G (2001) Improving urban food supply and distribution in developing countries: the role of city authorities. Habitat Int 25(3):431–446

Huynh TTT, Pham TMH, Duong TT, Hernandez R, Trinh TH, Nguyen MT, Even B, Lundy M, Swaans K, Raneri J, Hoang TK, Hendriks A, Abbink H, Nguyen TK, Ha HT, de Haan S (2021) Food systems profile. Along a rural-urban transect in North Vietnam. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/113417

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2018) World employment and social outlook: trends 2018. ILO, Geneva

IPES Food (2020) COVID-19 and the crisis in food systems: Symptoms, causes, and potential solutions. http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/COVID-19_CommuniqueEN%283%29.pdf. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

Jaffee S, Henson S, Unnevehr L, Grace D, Cassou E (2018) The safe food imperative: accelerating progress in low-and middle-income countries. World Bank Publications, Washington

Joshi A, Kaneko J, Usami Y (2012) Farmers’ participation in weekly organic bazaars in Aurangabad, India. J Rural Prob 45(175):231–236

Karg H, Akoto-Danso EK, Drechsel P, Abubakari AH, Buerkert A (2019) Food-and feed-based nutrient flows in two West African cities. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 115(2):173–188

Fan S, Swinnen J (2020) Reshaping food systems. The imperative of inclusiveness. In: International Food policy research institute, global Food policy report: building inclusive Food systems. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, pp 6–12. https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896293670

GNR (2020) Global Nutrition Report: Action on equity to end malnutrition. 2020. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives. https://globalnutritionreport.org/. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

Leeson GW (2018) The growth, ageing and urbanisation of our world. J Popul Ageing 11:107–115

Letcher TM (2020) Introduction to plastic waste and recycling. In: Plastic waste and recycling. Academic, London, pp 3–12

Lemeilleur, S., d’Angelo l.,Rousseau, M., Brisson E., Boyer A., Lançon F., Moustier P. 2019. Les systèmes de distribution alimentaire dans les pays d’Afrique méditerranéenne et Sub-saharienne. Repenser le rôle des marchés dans l’infrastructure commerciale. Notes techniques de l’AFD. Notes, (51). http://admin.riafco.org/Images/Ressources/Pulication/64/51-notes-techniques.pdf. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

Loc NTT, Moustier P (2016) Toward a restricted tolerance of street vending of food in Hanoi districts: the role of stakeholder dialogue. World Food Policy 2:67–78

Maertens M, Velde KV (2017) Contract-farming in staple food chains: the case of rice in Benin. World Dev 95:73–87

Maestre M, Poole N, Henson S (2017) Assessing food value chain pathways, linkages and impacts for better nutrition of vulnerable groups. Food Policy 68:31–39

Mangnus AC, Vervoort JM, McGreevy S, Ota K, Rupprecht C, Oga M, Kobayashi M (2019) New pathways for governing food system transformations: a pluralistic practice-based futures approach using visioning, back-casting, and serious gaming. Ecol Soc 24(4)

Minten B, Reardon T, Chen KZ (2017) Agricultural value chains: how cities reshape food systems. Global food policy report, IFPRI book, pp 42–49

Moustier P (2020) Pour un accès inclusif aux aliments en temps de covid-19. https://www.agenceecofin.com/agro/1205-76552-pour-un-acces-inclusif-aux-aliments-en-temps-de-covid-19-paule-moustier. Accessed on 1 Dec 21

Moustier P (2017a) Short urban food chains in developing countries: signs of the past or of the future? Nat Sci Soc 25(1):7–20

Moustier P (2017b) What market planning policies should apply to urban food systems in developing countries? In: Debru J, Albert S, Bricas N, Conaré D (eds) Urban food policies: proceedings of the international meeting on experience in Africa, Latin America and Asia. Chaire Unesco alimentations du monde, Montpellier, pp 23–26. https://issuu.com/chaireunescoadm/docs/01-actespau_en_20juin/32

Moustier P, Renting H (2015) Urban agriculture and short chain food marketing in developing countries. In: De Zeeuw H, Drechsel P (eds) Cities and agriculture. Developing resilient urban food systems. Routledge, London, pp 121–138

Moustier P, Figuié M, Loc NTT (2009) Are supermarkets poor-friendly? Debates and evidence from Vietnam. In: Lindgreen A, Hingley M (eds) The crisis of food brands. Gower Publishing, London, pp 311–327

Neveu-Tafforeau MJ (2017) Grande distribution: quelles opportunités pour les filières agroalimentaires locales? Fondation Farm, Paris

Nuthalapati CS, Sutradhar R, Reardon T, Qaim M (2020) Supermarket procurement and farmgate prices in India. World Dev 134(105034):1–14

OECD/SWAC (2020) Africa’s urbanisation dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography. West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en

OECD, Commission économique pour l’Amérique latine et les Caraibes, CAF Development Bank of Latin America and Union européenne (2019) Latin American economic outlook 2019: development in transition. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9ff18-en

Ogunkola IO, Imo UF, Obia HJ, Okolie EA, Lucero-Prisno DE III (2021) While flattening the curve and raising the line, Africa should not forget street vending practices. Health Promotion Perspect 11(1):32–35

Ortega DL, Tschirley DL (2017) Demand for food safety in emerging and developing countries: a research agenda for Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. J Agribusiness Dev Emerging Econ 7(1):21–34

Olivier DW, Heinecken L (2017) Beyond food security: women’s experiences of urban agriculture in Cape Town. Agric Hum Values 34(3):743–755

PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) (2015) Ultra-processed food and drink products in Latin America: trends, impact on obesity, policy implications, Washington, DC

Pallet D, Sainte-Beuve J (2016) Systèmes de transformation durables: quelles nouvelles stratégies pour les filières? In: Biénabé E, Rival A, Loeillet D (eds) Développement durable et filières tropicales. Editions Quae, Montpellier, pp 151–165

Pervin IA, Rahman SMM, Nepal M, Haque AKE, Karim H, Dhakal G (2020) Adapting to urban flooding: a case of two cities in South Asia. Water Policy 22(S1):162–188

Popoola AA, Adeyemi YD, Oni FE, Omojola O, Adeleye BM, Medayese S, Popoola OG (2021) Rural-urban Food movement: role of road transportation in Food chain analysis. In: Handbook of Research on Institution Development for Sustainable and Inclusive Economic Growth in Africa. IGI Global, pp 276–298

Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW (2012) Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 70(1):3–21

Pradeilles R, Irache A, Milkah N, Wanjohi HM, Laar A, Zotor F, Tandoh A, Senam KS, Graham F, Muthuri SK, Kimani-Murage EW, Coleman N, Green MA, Osei-Kwasi HA, Marco BM, Emily K, Rousham EK, Gershim AG, Akparibo R, Mensah K, Aryeetey R, Bricas N, Griffiths P (2021) Urban physical food environment drives dietary behaviours in Ghana and Kenya: a Photovoice study. Health Place 71:102647

Pulliat G (2015) Food securitization and urban agriculture in Hanoi (Vietnam). J Urban Res 7. https://journals.openedition.org/articulo/2845

Ravaillon M (2016) The economics of poverty. Paperback

Reardon T, Liverpool-Tasie LSO, Minten B (2021a) Quiet revolution by SMEs in the midstream of value chains in developing regions: wholesale markets, wholesalers, logistics, and processing. Food Security 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01224-1

Reardon T, Belton B, Liverpool-Tasie LSO, Lu L, Nuthalapati CS, Tasie O, Zilberman D (2021b) E-commerce’s fast-tracking diffusion and adaptation in developing countries. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 43:1243. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/aepp.13160

Reardon T, Echeverria R, Berdegué J, Minten B, Liverpool-Tasie S, Tschirley D, Zilberman D (2019) Rapid transformation of food systems in developing regions: highlighting the role of agricultural research and innovations. Agric Syst 172:47–59

Reardon T (2015) The hidden middle: the quiet revolution in the midstream of agrifood value chains in developing countries. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 31(1):45–63

Reardon T, Henson S, Gulati A (2010) Links between supermarkets and food prices, diet diversity and food safety in developing countries. In: Hawkes C, Blouin C, Henson S, Drager N, Dubé L (eds) Trade, food, diet and health: perspectives and policy options. Wiley, pp 111–130

Renting H, Dubbeling M (2013) Synthesis report: innovative experiences with (peri-) urban agriculture and urban food provisioning - lessons to be learned from the global South. Supurbfood project report. Leusden, RUAF Foundation

Reynolds TW, Waddington SR, Anderson CL, Chew A, True Z, Cullen A (2015) Environmental impacts and constraints associated with the production of major food crops in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Food Security 7(4):795–822

Rodrik D (2016) Premature desindustrialization. J Econ Growth 21(1):1–33

Rousham E, Pradeilles R, Akparibo R, Aryeetey R, Bash K, Booth A, Muthuri S, Osei-Kwasi HA, Marr C, Norris T, Holdsworth M (2020) Dietary behaviours in the context of nutrition transition: a systematic review and meta-analysis in two African countries. Public Health Nutr:1–17

Seck PA (2021) Some African expectations from the 2021 world summit on food systems. Embassy of Senegal at Italy

Schreiber K, Hickey GM, Metson GS, Robinson BE, MacDonald GK (2021) Quantifying the foodshed: a systematic review of urban food flow and local food self-sufficiency research. Environ Res Lett 16(2):023003

Shekar M, Condo J, Pate MA, Nishtar S (2021) Maternal and child undernutrition: progress hinges on supporting women and more implementation research. Lancet 397(10282):1329–1331

Sirdey N (2020) Pour une analyse des « systèmes alimentaires du milieu »: étude de la pertinence et de l’opérationnalisation de la notion en contexte africain. Document de travail Cirad

Si Z, Scott S, McCordic C (2019) Wet markets, supermarkets and alternative food sources: consumers’ food access in Nanjing, China. Can J Dev Stud 40(1):78–96

Sonnino R, Tegoni CL, De Cunto A (2019) The challenge of systemic food change: insights from cities. Cities 85:110–116

Soula A, Yount-André C, Lepiller O, Bricas N (eds) (2020) Manger en ville: Regards socio-anthropologiques d’Afrique, d’Amérique latine et d’Asie. Editions Quae, Montpellier

Tangworamongkon C (2014) Street vending in Bangkok: legal and policy frameworks, livelihood challenges and collective responses. Woman in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/Street-Vending-Bangkok-Legal-and-Policy-Framework-Law-Case-Study.pdf

Tefft J, Jonasova M, Adjao R, Morgan A (2017) Food systems for an urbanizing world. World Bank and FAO

The EAT-Lancet Commission (2019) Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet Commissions. https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/EAT

The World Bank (2016) Linking farmers to markets through productive alliances: an assessment of the World Bank experience in Latin America. World Bank, Washington DC

Tschirley D, Bricas N, Sauer C, Reardon T (2020) Opportunities in Africa’s growing urban food markets. In: feeding Africa’s cities: opportunities, challenges, and policies for linking African farmers with growing urban food markets. AGRA. Nairobi: AGRA, 25-56. Africa agriculture status report. https://agra.org/reports-and-financials/

Tschirley D, Haggblade S, Reardon T (2014) Africa’s emerging food transformation, Eastern and Southern Africa. MSU. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/global-food/research/international-development/vietnam-consumer-survey

Turner S, Schoenberger L (2011) Street vendor livelihoods and everyday politics in Hanoi, Vietnam: the seeds of a diverse economy? Urban Stud 49(5):1027–1044

UNICEF/GAIN (2018) Food systems for children and adolescents. Summary report

University of Adelaide (2014) The Vietnam urban food consumption and expenditure studyFactsheet 4: where do consumers shop? Wet markets still dominate. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/global-food/ua/media/95/Urban_Consumer_Survey_Factsheet_04.pdf

Valette E, Philifert P (2014) L’agriculture urbaine: un impensé des politiques publiques marocaines? Géocarrefour 89:75–83

Verger EO, Perignon M, El Ati J, Darmon N, Dop MC, Drogué S, Amiot-Carlin MJ (2018) A “fork-to-farm” multi-scale approach to promote sustainable food systems for nutrition and health: a perspective for the Mediterranean region. Front Nutr 5:30

Vietnam news (2021) Agricultural products go online. https://vietnamnews.vn/economy/899756/agricultural-products-go-online.html

Vorley B (2013) Meeting small-scale farmers in their markets: understanding and improving the institutions and governance of informal agrifood trade. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED)

Wanyama R, Gödecke T, Chege CG, Qaim. (2019) How important are supermarkets for the diets of the urban poor in Africa? Food Security 11(6):1339–1353

Wertheim-Heck SC, Raneri JE (2019) A cross-disciplinary mixed-method approach to understand how food retail environment transformations influence food choice and intake among the urban poor: experiences from Vietnam. Appetite 142:104370

Yaya S, Ekholuenetale M, Bishwajit G (2018) Differentials in prevalence and correlates of metabolic risk factors of non-communicable diseases among women in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from 33 countries. BMC Public Health 18(1):1–13

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ninon Sirdey, two anonymous reviewers from the UNFSS scientific group for their comments on an earlier version, and to Jemimah Njuki, International Food Policy Research Institute, Africa Regional office c/o ILRI Nairobi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Moustier, P. et al. (2023). Priorities for Inclusive Urban Food System Transformations in the Global South. In: von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L.O., Hassan, M.H.A. (eds) Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15702-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15703-5

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)