Abstract

Japan finds itself in a double bind. On the one hand, the United States (US) has been a committed military ally, guaranteeing the national security of Japan since 1952. Any discussion of abandonment by the US sends shockwaves throughout the conservative security establishment of Japan. On the other hand, the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has transformed it into the most important trade partner of Japan, by far. Japan is interested in a continued expansion of the PRC economy. This paper analyzes the foreign economic policy of Japan and the security policy of the conservative, LDP-led governments under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe (2012–2020) and his successors in this complex interplay of international relations and national politics.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Japan finds itself in a double bind. On the one hand, the United States (US) has been a committed military ally, guaranteeing the national security of Japan since 1952. Any discussion of abandonment by the US sends shockwaves throughout the conservative security establishment of Japan. On the other hand, the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has transformed it into the most important trade partner of Japan, by far. Japan is interested in a continued expansion of the PRC economy. Its markets are crucial for Japanese industries and promise future profits, whereas the declining population in Japan will hardly generate any future economic growth. The heated strategic competition between the US and the PRC has tightened the double bind. It is difficult to imagine how Japan could confront this inherent dilemma and resolve the situation. One might have hoped that the sandwich position that Japan finds itself in between the US hegemon and Chinese contender would allow it to play a mediating role. Given the escalating strategic rivalry between the US and PRC, some might even assign blame to Japan for completely failing in this aspect.

Aside from the question of whether Japan would ever have been accepted by the PRC as an intermediary because of their bilateral historical issues and its security alliance with the US, it must be stressed that Japan was not just a passive “victim” of rising US-Chinese rivalry. On the contrary, it played an active role that welcomed an increasingly assertive position of the US vis-à-vis the PRC, especially during the government of Shinzō Abe (2012–2020). In fact, the conservative security establishment of Japan has good reasons to welcome the new US approach to Beijing, given the increasingly assertive stance of the PRC in East and Southeast Asia as well as its territorial conflicts with other countries in the region, including Japan. However, the conservative security establishment does not represent the whole conservative establishment in Japan, and its business community has much to lose from disintegrating economic relations with the PRC.

The picture becomes even more complicated when looking beyond the conservative elites themselves. Shared growth was established as the new social contract in Japan between the conservative establishment and the population after the crushing defeat in the reckless expansion wars up to 1945. This social contract guaranteed the delivery of the fruits of economic expansion and hard work to the general population in the form of prosperity and increasing purchasing power combined with a very defensive and limited security policy that leaned on US support. The successful realization of the promises of the social contract regarding general well-being was the foundation of the continuing dominance of elections and politics by the conservative establishment and its Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). In recent years, power has become concentrated and consolidated in the hands of the prime minister and his entourage, which never occurred in modern times. In Japan, this is called the kanteishugi (literally the Residence-ism of the Prime Minister). Still, Japan’s executive remains bound by democratic constraints. The conservative establishment and the LDP cannot ignore the economic priorities and wishes of the voters if they want to remain in power in the Japanese democracy. This is primarily due the increasingly low growth and standstill in social upgrading in recent decades, which have led to narratives of “lost decades” and perception of Japan as a “gap society” marked by social differences and increasing social exclusion (Chiavacci 2021, 2022).

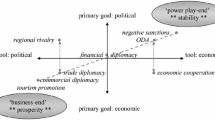

This paper analyzes the foreign economic policy of Japan and the security policy of the conservative, LDP-led governments under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe (2012–2020) and his successors in this complex interplay of international relations and national politics. The theoretical framework of this analysis uses the concepts of the balancing-hedging-bandwagoning continuum (see Fig. 9.1), which has been proposed by Bloomfield (2016) and others.

During the decade of conservative governance, the Japanese security policy included a strategy in the balancing zone between hard balancing and containment toward the PRC and a strategy in the bandwagoning zone between allied alignment and dependence toward the US. However, Japan followed both the PRC and US strategy in the hedging zone between dominance denial and economic pragmatism in its foreign economic policy. Furthermore, Japanese foreign policy was not just reactive during this decade, as famously postulated by Calder (1988), but very proactive. Japan was not just carefully navigating its double bind but actively riding it. Under Abe, it played an increasingly influential role in international trade and security policy (e.g., Funabashi and Ikenberry 2020). It remains to be seen if this proactive foreign policy will continue after Abe. One precondition for such an assertive foreign policy, which cannot be taken as a certainty, is that longer terms of office for the Japanese Prime Minister become the rule, as was the case with Abe.

Path-Dependency and Shifts in the Ideational Map of the Japanese Foreign Policy

In order to understand the new directions in Japanese foreign policy in the last decade, a quick assessment of the redefinition of Japan after its expansion wars defeat, following the 1945 detonation of the two atomic bombs (Chiavacci 2007), is required. Due to the complete failure of the previous strategy of gaining a dominant position in East Asia, a leading role in the world system as a military superpower was no longer sustainable. During the US-led allied occupation, the reform policies unleashed the left-wing that gratefully accepted the new constitution and its article 9 written by the US that envisaged a demilitarized and peaceful Japan. The progressive left embarked on transforming Japan into a neutral country pertaining neither to the capitalist nor the communist bloc during the Cold War (Stockwin 1962). However, the conservative establishment did not want to know anything about this idea and was finally able to establish the Yoshida doctrine as a new blueprint for the future of Japan. This doctrine, named after the influential Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida (1946–1947 and 1948–1954), focused on the economic rebuilding of Japan (Pyle 1992). The doctrine also accepted the submission of Japan under US leadership in foreign and security policy regarding allied alignment and even dependence in the bandwagoning zone.

Still, this prioritization of economic growth and acceptance of dependence on US protection as well as a semi-sovereignty with respect to the stationing of US troops in Japan, even after the end of the occupation period in 1952, was not popular in the whole conservative establishment. For instance, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi (1957–1960), a member of the war elite, tried to re-establish Japan as a partner on more equal footing to the US through limited bandwagoning when renewing the bilateral security treaty in 1960. This led to a huge national protest movement that shook the foundations of the democratic institutions in Japan (Kapur 2018; Saruya 2021). Kishi finally pushed through the renewal but had to resign as prime minister and renounce his plan for a “normal” Japan with a strong military and autonomous security policy. His successor, Hayato Ikeda (1960–1964), not only refocused on the Yoshida doctrine but socially embedded this doctrine by making the conservative establishment and its LDP into the guarantor and champion of shared growth (Chiavacci 2007; Pyle 1992). Rebuilding national greatness and prestige through the economic development of Japan was no longer the goal with Ikeda. Focusing all available resources on economic growth of Japan became now a strategy for general well-being and a good life. Ikeda pulled together the compromise, which became the social contract of the following decades. It allowed Japan to overcome the fierce struggles between conservative employers and left-wing labor unions and to rise from the ashes of war and destruction to become an economic and technological superpower.

In the years leading up to the 1990s, the main disparity in the foreign and security policies remained between the pacifists (Socialist Party Japan and Communist Party Japan) and middle-power internationalists (LDP and Yoshida doctrine). Still, both sides agreed on prioritizing economic development over remilitarization. However, new discourses on the future foreign and security policies of Japan arose in the conservative establishment following the Cold War (Samuels 2007). As Japan’s role in the Gulf War (1990–1991) was regarded by many in the conservative establishment as a fiasco and humiliation, they started to push for fundamental reforms in the security policy of Japan. The first group of leading conservative politicians, such as Shinzō Abe, Junichirō Koizumi and Ichirō Ozawa, wanted to transform Japan into a normal state, basically picking up the Kishi vision for a remilitarized Japan as more of an equal partner to the US. The second group of far-right politicians, most prominently Shintarō Ishihara, Governor of Tokyo (1999–2012), wanted to go even further and re-establish Japan as a fully sovereign and autonomous nation by repealing the security treaty with the US and sending the US troops home. The goal of this group was no longer an allied alignment with the US but outright dominance denial (Fig. 9.1).

Normal nationalism then began dominating Japanese foreign and security policy. In a kind of salami tactic, they began cutting off more and more slices of the Yoshida doctrine, such as sending Japanese troops overseas or establishing a new Ministry of Defense. However, the international environment and national development changed in a short time, which redrew the map of foreign and security policy discourses in Japan. The economic and political rise of the PRC and Japan’s economic stagnation fundamentally changed the game board on which Japan was playing. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Japan stagnated since the mid-1990s, the PRC began its ascendance and overtook Japan in 2009 (Urata 2020: 149). In parallel, the military expenditures of the PRC began exceeding the spending of Japan many times over.

However, the rise of the PRC was not just a bad story for Japan. Bilateral trade multiplied, and many Japanese companies profited from the new business opportunities in the PRC. According to the GDP in US$, as an indicator, the Japanese economy was stagnating, but Japanese investments and business activities abroad and especially in the PRC increased. Therefore, lost decades for Japanese business interests can hardly be discussed if foreign activities are taken into consideration. The rise of the PRC was, in other words, a huge opportunity for the Japanese economy. This led to a double bind for Japan and the question involving how Japan should position itself and hedge, given the risks and opportunities arising from the rise of the PRC and continuing importance of the bilateral relationship with the US (Michishita and Samuels 2012).

The main strategic question involved the priorities chosen in this dual hedge of further economic integration with the PRC and maintaining strong security relations with the US. Initially, the priority was set by the conservative establishment on security. For example, due to the more assertive foreign and maritime policy of the PRC, Japan began developing a more security-oriented and active administration of its extended maritime zones in the mid-2000s (Manicom 2010). However, the late 2000s marked a political earthquake in Japan. The progressive Democratic Party Japan (DPJ) defeated the conservative establishment in the lower house election in a landslide victory (Chiavacci 2010; Shiratori 2010). This proved that the LDP was not invincible, even though it had been nearly uninterrupted in power for over 50 years since its founding in 1955. Its neoliberal reform policies, introduced from the late 1990s onward and further strengthened under Koizumi in the early 2000s, came increasingly under criticism for producing a “gap society” (kakusa shakai) in the mid-2000s marked by increasing social inequality and polarization and for leaving rural areas to decay. The LDP no longer seemed to be a guarantor of shared growth. The DPJ, under the strategic leadership of Ozawa, mainly used the feeling of decoupling from national growth in the countryside to inflict crushing defeats on the LDP in the 2007 upper house and 2009 lower house elections. The new Prime Minister of the DPJ, Yukio Hatoyama, focused his foreign policy on economics by favoring economic development and prioritizing stronger links to Asia and the rising PRC over the declining US (Liff 2019). His “friendship diplomacy” (yuai gaikō) tried to achieve in his own words “coexistence and co-prosperity with countries that have different values from Japan while recognizing each other’s position” (quoted after Tsai 2012: 262). This attempt to move Japan toward limited bandwagoning with the US and economic pragmatism with the PRC not only caused adverse reactions from Washington but also did not find strong resonance with Beijing. On the contrary, the relations between Japan and the PRC strongly deteriorated from 2010 onward. After a collision between a Chinese trawler and Japanese Coast Guard patrol boats near the Senkaku Islands, the territorial conflict regarding these islands, which are under Japanese control but also claimed by the PRC and Taiwan, heated up and reached a whole new level. When the Japanese government purchased the Senkaku Islands from its private owner in 2012, the number of Chinese vessels and airplanes entering the territorial waters and airspace near the island significantly increased, which led to the risk of escalation and war engagement with Japanese units. The conservatives in the Japanese security establishment saw their position fully confirmed. The US was needed more than ever as a strong partner to Japan, and the PRC was a threat to national security and could not be trusted. Right-wing politicians, such as Shintarō Ishihara (2013) ridiculed the “naïve” DPJ approach toward Beijing.

In 2012, when Abe was re-elected as LDP President and led the LDP to a victorious election campaign, many pundits were seriously nervous because of his rise to power. In his election campaign, Abe had promised to “take Japan back” to the good old times. Given the conflicts over the Senkaku Islands with the PRC that had escalated during the DPJ government, Abe seemed to be an international risk factor to peace in East Asia. He was known for his revisionist ideas about the wartime history of Japan, for his nationalist position on the right of the LDP, and for his hawkish wish to re-establish Japan as a normal military power, ready to use force to achieve foreign policy goals. These seemed to be bad ingredients in light of the unstable situation with the PRC in September 2012. The Economist (2012) was not the only commentator that was alarmed: “Could China and Japan really go to war over these [Senkaku Islands]? Sadly yes.” Some observers even compared the situation in East Asia with the situation in Europe leading to the First World War in 1914. Fortunately, both sides kept their composure, and war never materialized. Still, the Abe administration refocused their attention on security issues over economic considerations preferring a military hedge by maintaining the security treaty with the US and keeping distance from the PRC. It reformulated the double hedge of Japan by making it a full partner with the US and starting an active containment policy vis-à-vis the PRC. Japan, under Abe, was even able to recruit the US as a partner for a PRC containment policy. The institutional changes in the national polity of Japan that handed Shinzō Abe the institutional requirements for reformulating Japanese security and foreign policy were vital for this turn toward an active security policy in Japan.

The Rise of a Core Executive

In his classical analysis of Japan, as a reactive state that is not formulating a strategic, proactive foreign policy but primarily reacting to foreign pressure, Calder (1988: 528) identified the fragmented character of state authority as “perhaps [the] most important” factor. In comparison with the US President that has all the capabilities of being a strong chief executive and of setting strategic goals in foreign policy, the Japanese Prime Minister and his Cabinet lack power and are confronted with a fragmented bureaucracy in which ministries are neither cooperating nor coordinating. Instead, they often undermine the competencies of each other and engage in open conflicts when invading policy fields. Illustrative in this context is the joke by an Australian minister in an official speech in 1992, in which he pointed out that the Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) had not only a three-China problem (PRC, Hongkong and Taiwan) but also a two-Japan problem (Krauss 2003: 327). At the time, Japan always sent two delegations to the APEC meetings that did not coordinate and often made contradictory proposals. These two “independent” delegations came from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

Many Japanese commentators and politicians had similar perspectives like Calder (1988). Even members of the conservative elite identified a basic deficit in the Japanese political system dominated by sectorial interests, which led to an inability to formulate a long-term strategic economic policy and proactive foreign policy. They demanded institutional reforms in the polity of Japan, which should strengthen the core executive (Ozawa 1993; Sakakibara 2008). Accordingly, Japanese politics in the 1990s were characterized by institutional reforms. The main thrust of these reforms was to strengthen the prime minister and his cabinet as the executive. This centralization of political decision-making was regarded as important to overcome the influence of interest groups and accompanying clientelism for making the path free for structural economic reforms and to develop a more strategic and active foreign policy. The central goal was to move policymaking away from the established insider circles of LDP lobby politicians—organized in tribes, bureaucrats and organized interest groups—toward a dominant cabinet with control over the LDP rank politicians and the bureaucracy (Tanaka 2019). A new political center should develop an overarching national policy agenda and overcome particularistic interests and fragmentation, which have marked Japanese politics since the 1970s. The comprehensive administrative reform of 1997, which was fully implemented in the four years leading up to 2001, reshuffled ministries and concentrated more resources in the hand of the prime minister and the cabinet. The legislative initiatives of the prime minister were legally enshrined and support for developing a political agenda expanded significantly by increasing the administrative staff (Shinoda 2005, 2013).

During his years as Prime Minister, Junichirō Koizumi (2001–2006) showed that the institutional change allowed the prime minister to have a much bigger say in policy and decision-making with his far-reaching economic reform agenda and active foreign policy. However, his six successors—three LDP and three DPJ Prime Ministers—up to 2012, including Abe during his first time as prime minister (2006–2007), remained approximately one short year in office and could hardly leave behind a lasting influence on Japanese politics. The reforms had given the prime minister and his executive core team much more power. However, to put these new capabilities into practice, the stability and continuity of a prime minister were needed. With the position of prime minister again a revolving door after Koizumi, Japan seemed to fall back into unstable governments and decentralized decision-making. The prime minister and cabinet became a plaything of interest groups and internal party disputes, unable to impose or even develop a comprehensive strategy.

However, the second tenure of Shinzō Abe lasted eight years until September 2020. This made him not only the longest-serving prime minister of Japan, but he was able to concentrate power in the core executive like no other Japanese leader after 1945. During his second time as prime minister, he established a strong grip on the ministerial bureaucracy, the LDP and interest groups. The concentration of decision-making power in the core executive was even significantly stronger than in the years of the Koizumi administration in the early 2000s. Japan now had a full-fledged core executive that dominated economic and foreign policy (George Mulgan 2018; Iio 2019; Takenaka 2019). Due to several political scandals, commentators increasingly questioned whether the power concentration in the hand of the prime minister and the core executive under Abe had gone too far. National administration seemed to increasingly function in a system of “anticipatory obedience” (sontaku) toward Abe and his entourage, even if this meant that the bureaucrats were no longer fully following legal provisions and procedures (Carlson 2020; Iio 2019). Some commentators even regarded Abe and his government as a risk for Japanese democracy (Banno and Yamaguchi 2014; Kolmaš 2018). They emphasized his personal, revisionist convictions that downplayed Japanese historical errors and acts of violence during its expansion wars. He and his cabinet were very close to right-wing ideas like those of Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), an ultra-conservative and nationalist organization in which many leading members of the conservative establishment, including Abe, are affiliated. Critics of Abe also pointed to his fierce attacks on progressive mass media, whose reporting was not to his liking or sympathetic toward his policies, as an undermining of a free press system (Kingston 2017).

However, Abe’s original agenda collided with the will of the people and the checks and balances involved in Japanese democratic institutions. He and his core executive have, without a doubt, left their mark on Japanese foreign policy regarding security questions and economic questions. Still, despite his long tenure and the unprecedented power concentration in his hands, Abe was also forced to redraft some policy goals. Additionally, he could not fully realize all his central policy goals. Let us first examine the security policy under the Abe administrations.

Introducing the Abe Doctrine

During his first term as prime minister in 2006–2007, Abe introduced one major reform in security policy. He upgraded the Defense Department—a subdivision of the Cabinet Office without a seat in the cabinet—into the Ministry of Defense with a defense minister as part of the core executive. In this short year, he also introduced the idea of a value-based foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific, which is regarded as the origin of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy today. Still, despite the high expectations of Abe at his inauguration, his first term as prime minister can hardly be described as successful. Due to falling support, poor elections results and health issues, he was forced to step down after 12 short months in September 2007 to make way for a new LDP Prime Minister.

Given this record, he was not unanimously elected as party president and leading candidate by the LDP, then in opposition, for the upcoming lower house elections in 2012. Not everyone in the LDP was convinced that Abe was the right candidate to bring the party back into power. In fact, in the first round, he only obtained 29% of the party member votes, far behind the 55% of the leading candidate (Endo et al. 2013: 54). Still, Abe finally won, thanks to the support of LDP Diet members. He then led the LDP to an election victory and back into government (for details of the 2012 election, see Pekkanen et al. 2013). The US government generally welcomed the return of the LDP to power as the party that stands for a stable security partnership between Japan and the US. However, as discussed above, there was some nervousness about Abe, concerning his nationalistic agenda and hawkish approach to foreign policy, especially in view of the heated and virulent conflict around the Senkaku Islands. Abe was perceived as a risk factor that had to be tamed. When he visited the Yasukuni Shrine in late December 2013, this led (as expected) to fierce criticism by the PRC and South Korea. However, for his shrine visit Abe was also subjected to a public rebuke by the US. The Yasukuni Shrine celebrates those who have fallen during war conflicts on the Japanese side. However, it also represents a revisionist historical perspective because the war criminals sentenced to death at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal (1946–1948) were also included in the shrine in the 1970s. Through this action, war criminals were de facto transformed into soldiers that have honorably fallen for Japan, an action which has infuriated countries such as China and South Korea, both victims of Japanese expansionism and imperialism. Although conservative Japanese Prime Ministers and Ministers had been visiting the shrine since the mid-1970s, public criticism from Washington came for the first time after such a visit in 2013, expressing “disappointment” over the behavior of Abe (Smith 2015: 58). Conspicuously, Abe never visited the shrine again, during the rest of his tenure as prime minister.

Still, the reforms and fundamental reorientation of the security policy of Japan in the eight years under Abe were most welcomed by the US government. The two main reforms in the field of security policy by the Abe government were the introduction of the State Secrecy Law (Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets, Tokutei Himitsu no Hogo ni kan suru Hōritsu) of 2013 and the new Japanese military legislation (Legislation for Peace and Security, Heiwa Anzen Hōsei) of 2015. The latter reinterpreted Article 9 and allowed the Japanese Self-Defense Forces to operate overseas and engage in collective self-defense with allies. The US embraced both reforms as fundamental improvements for the security collaboration between the US and Japan. In fact, the US government had pressured Japan to control classified information more tightly, similar to what was done with the State Secrecy Law as a prerequisite for more information sharing and cooperation between the two partners (Williams 2013). The new military legislation and reinterpretation of the constitution allowed Japan to send its army and navy to support the US in the case of an attack on US troops, for example, in the Taiwan Strait. It marked a fundamental switch in the security relationship. The US nuclear shield and the US troops stationed in Japan led, in the postwar era on the one hand, to a dependence of Japan on the US for its security. On the other hand, Japan tried to keep some distance from the US to avoid being drawn into its military conflicts. In the balancing-hedging-bandwagoning continuum (see Fig. 9.1), Japan was in a state of dependence on its US partner regarding its national security. However, at the same time, it restricted its external security support from the US by invoking Article 9 to limit bandwagoning and, if possible, even only binding engagement. The new defense posture of collective self-defense changed its position regarding the external security support of its US partner into an allied alignment in the zone of bandwagoning. These reforms under Abe marked a turn toward a proactive security policy and were so far-reaching that some authors argue that Japan had now overthrown the Yoshida doctrine and switched to a new Abe doctrine (Akimoto 2018; Hughes 2015).

However, both legislations led to a public backlash and the rise of oppositional social movements not seen in decades in the field of security policy. According to representative national opinion polls by Japanese newspapers, a clear majority of the Japanese population opposed the State Secrecy Law, and support rates could not even garner 30% (Nihon Keizai Shinbun 2013; Suzuki 2013). Critics regarded the law as a turn toward state authoritarianism and militarism similar to the period up to 1945 and feared a gradual undermining of the democratic checks and balances as well as public information disclosure. In 2015, approximately two-thirds of the population rejected the new Legislation for Peace and Security (Soble 2015). The Abe government pushed the legislation through the parliaments, but a population majority and the overwhelming majority of constitutional scholars rejected the new bill as a distorted interpretation of Article 9 and outright anti-constitutional (Kokubu 2015). A public protest movement against the Abe policies gained increasing momentum and staged demonstrations that resembled the peak of public protest during the renewal of the security treaty under Kishi in the late 1950s (Chiavacci and Grano 2020; Chiavacci and Obinger 2018).

In this context, even business interests, usually an unshakeable ally and long-time supporter of the LPD, were rather reluctant to endorse the new security agenda of Abe fully. The Abe administration lifted the ban on arms exports in 2014. It tried to promote more weapon exports by Japanese producers to potential allies in East and South-East Asia to restrain the rise of the PRC and increase influence in the region. However, Japanese weapon producers like Mitsubishi Heavy Industry or Kawasaki Heavy Industry were not fully supportive of this new export strategy. As defense-related sales were less than 10 percent of their total revenues, they were afraid that massive weapon exports might lead to a more negative public image and hurt their business interests in civilian sales (Sakaki and Maslow 2021).

Constitutional reform, the main goal of Abe, became a central political issue. After the Legislation for Peace and Security was passed, surveys consistently show that public opinion in reaction to the security policy reforms became more opposed to constitutional reform and reformulating or complementing Article 9 (Suzuki and Wallace 2018: 730). Only eight days before the 2017 lower house election was called, a new center-left party was founded as part of a major reorganization of the opposition parties, which called itself the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP). This name was a clear reference to the new party position of defending the Japanese constitution, including Article 9 and its democratic institutions. Surprisingly, despite its organizational weakness and poorly conceived election agenda due to its short-term establishment, the CDP had notable electoral success and became the second largest party in the new lower house (Pekkanen and Reed 2018). Given the public opinion and these developments, even voices inside the conservative LDP establishment called for a postponement regarding any amendment or reformulation of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution (Ishiba 2017). It became clear that constitutional reform, which requires not only a two-thirds majority in both chambers of the parliament but also a majority in a national referendum, was hardly realizable and would be a huge political risk for the LDP. Abe successfully pushed through an Abe doctrine and strengthened the US-Japanese security alliance. However, his action led to popular pushback that impeded any possibility of constitutional reform, and especially of amending or reformulating Article 9. As was the case with his grandfather Kishi, the ultimate goal of Abe was to “normalize” Japan and its security policy and build a new foundation for the alliance with the US, especially given the rising PRC. However, it remained an unrealizable dream.

Although the domestic road for normalization became closed, the election of Donald Trump as US President opened a new opportunity in the international arena. Prior to the inauguration of Trump in January 2017, Abe met with him in November 2016 to initiate a good relationship. Abe personally invested significant time and resources into the relationship with Trump. Obviously, Abe saw in Trump a US President that took a much more aggressive stance toward the PRC. His goal was not only to develop and maintain a good personal relation with Trump and strengthen the Japan-US security relationship but also to pull the US, under Trump, toward a more active containment policy of the PRC, consistent with his view of a rising China as a security risk. The proactive security policy of Abe proved to be quite successful. Japan was able to skillfully navigate the space between US hegemony and Chinese contenders and even shape the US-Chinese rivalry by riding it. Under Abe, Japan could mold the US security policy and its rivalry with the PRC, to some extent, by adding new strategies and revitalizing partnerships.

The main success stories of the initiatives by Abe in this context were the FOIP strategy as well as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) between Australia, India, Japan and the US. The strategy and dialogue originated during the first tenure of Abe as Prime Minister in 2006–2007. The FOIP had its origin in the “Arc of Freedom and Prosperity,” which was declared as a new departure to Japanese foreign policy in November 2006, by Foreign Minister Tarō Asō (2006):

[W]e are aiming to add a new pillar upon which our policy will revolve. First of all, there is ‘value-oriented diplomacy,’ which involves placing emphasis on the ‘universal values’ such as democracy, freedom, human rights, the rule of law, and the market economy as we advance our diplomatic endeavors. And second, there are the successfully budding democracies that line the outer rim of the Eurasian continent, forming an arc. Here Japan wants to design an ‘arc of freedom and prosperity.’ Indeed, I believe that we must create just such an arc.

This envisaged arc from Japan over Southeast Asia and India to Europe excluded the PRC and was openly a policy to encircle it (Hosoya 2011). The FOIP was introduced by Abe in August 2016 and had many continuities with its predecessor by trying to establish a rule-based order against increasing Chinese interference and territorial claims in the important sea-lanes for Japan in the Pacific and Indian Oceans (Abe 2016):

What will give stability and prosperity to the world is none other than the enormous liveliness brought forth through the union of two free and open oceans and two continents. Japan bears the responsibility of fostering the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and of Asia and Africa into a place that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion, and making it prosperous.

Abe successfully promoted this concept to Trump. In fact, it made its way into the December 2017 US National Security Strategy and was adopted by the US under Trump as part of a PRC containment policy.

Abe had also initiated the QUAD in 2007. It was regarded as a response to increased Chinese economic and military power. In fact, after its announcement in 2007, the PRC even issued formal diplomatic protest to QUAD members. After the first round of dialogue and military exercise, the forum of the QUAD ceased due to the withdrawal of Australia. However, cooperation, including military exercise, continued between the three remaining partners. From 2013 onward, Abe began his efforts to re-establish the QUAD. Finally, in November 2017, the QUAD was restarted concurrently with the establishment of the FOIP.

Overall, Abe has achieved many of his goals in national security policy and played an important, sometimes even pivotal role on the international level. Under him, Japanese foreign policy was everything other than reactive. However, he could not realize his primary goal of a revised constitution as a new foundation for Japan as a normal state. Furthermore, he also had to devote much energy and time to economic policy and, as one outcome of this, had to adapt his China policy.

Abenomics for Winning Elections

The long tenure of Abe as Prime Minister and President of the LDP was due to his ability to deliver victories for the conservative establishment. In contrast to the crushing defeat of the LDP under him in 2007, he leaded the LDP successfully in no less than six national elections for the lower and upper house of the parliament in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017 and 2019 during his second term as prime minister. However, the LDP successes in the elections under his leadership were not due to his security agenda. As a result of the aforementioned negative public perception, one can even say that the election victories were despite the reforms in security policy. What made the LDP and Abe primarily attractive for voters was his economic policy called Abenomics, with its three arrows that promised to bring Japan back on a path of sustained and shared growth without many painful structural reforms (Chiavacci 2021, 2022; Shibata 2017). In short, Abe imagined his tenure to accomplish the normalization of Japan as envisioned by his grandfather Kishi but ended up following the steps of Ikeda by focusing and stressing on economic policies. He even formulated innovative ideas for enhancing social policy despite his very conservative social and political value preferences, such as womenomics for promoting labor market participation and career opportunities for women (Takeda 2018).

This “social turn” (Katada and Cheung 2018) was not a complete contradiction to his security agenda. Given the decreasing Japanese population and demographic projections of a population implosion in the coming decades (Funabashi 2018), it became imperative for Japanese security policy to secure the population size and economic foundation. The Abenomics 2.0, presented as an updated version of Abenomics in September 2015, introduced more support for young families, to raise the fertility rate and to prevent the population from falling below a level of 100 million. It appeared on paper as an attempt to move the Japanese welfare state toward a social-democratic welfare regime but was never really followed up by substantial reforms and resources.

Although the election of Trump in 2016 was a window of opportunity in security policy for Abe, Trump, as President, was a double shock for the Abe government and Japan in the field of economics and trade policy. Similar to the Western partners of the US, it was a shock because Trump transformed the US foreign policy fundamentally. Under him, the US turned from a hegemon guaranteeing international institutions and the world trade order into a power that openly disregarded many international rules and tried to use its power, especially in trade, to impose its interest on others. The Trump slogan “America First” meant a strong focus on the red numbers of the US in bilateral trade with the PRC, and also that the US-trade deficit with Japan would receive strong attention and come under increasing pressure. Specifically, it was also a shock for the Japanese conservative establishment because it broke the basic rule that a Republican President was better for Japanese-American relations. After all, he would focus more on the bilateral security agenda and less on bilateral trade issues that had become very contentious since the 1980s (Chiavacci 2018; Urata 2020). However, Republican President Trump made the US trade deficits an issue of the highest importance in his political agenda. Despite the charm offensive of Abe on Trump, Japan could not completely escape this US pressure and was forced to sign a bilateral trade agreement with the US in 2019. Still, through his intensive diplomacy, Abe and Japan were able to sidestep the most incisive demands from the US side.

Moreover, Trump withdrew the US from the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which had been highly controversial in Japan (Solís and Urata 2018; Tashiro 2013). Agricultural interests, a main support group of the LDP, opposed this agreement and regarded it as another nail in the coffin of Japanese agriculture. Despite angering his rural clientele, Abe had pushed very hard for Japan to join the CPTPP due to trade policy considerations. His government hoped that the CPTPP would form an economic bloc led by the US that could contain Chinese (future) influence on international standards in trade and investment. As a result of the US turning away from a free trade policy, Japan became an unexpected champion of open trade under Abe (Solís 2020). Not only did Japan play a pivotal role in realizing the CPTPP after the US withdrawal, but it also signed a Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement in 2018, which had been regarded as very complicated before. Because of the US absence, Japan changed in trade policy from a rather reactive side-actor to a proactive and important player in world trade politics.

Economic considerations also led to a re-rapprochement between Japan and the PRC. From an icy and even hostile relationship in the early years of the Abe government, a working relationship was established. Given the increasingly aggressive hostility from the US, the PRC started to change its attitude toward Japan. For Japan and Abe, the Chinese market was too important to be ignored, considering the significance of generating a favorable economic development for winning elections. In 2007, the PRC had overtaken the US as the most important trade partner of Japan. According to Japanese trade statistics, Japanese trade with the PRC is approximately 60% larger than its trade with the US in recent years. The growth of the PRC has been a huge opportunity for many Japanese companies and was in recent years one of the most important drives for Japanese economic growth. Without COVID-19 and the new Hong Kong national security law, the working relationship with Beijing would have even culminated in an official state visit of the Chinese President Xi Jinping in Japan. Something that seemed hardly possible to consider at the beginning of the Abe years, when his meetings with Xi were showcases of mutual dislike. In accordance with the re-rapprochement to the PRC, the Japanese FOIP vision has evolved in the late years of the time in power of Abe. The FOIP changed into a concept seeking to maintain an open and inclusive regional order that incorporates all regional powers, including the PRC (Hosoya 2019; Satake and Sahashi 2021). The recent signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in November 2020, which includes the PRC and Australia but not the US, is another constituent step in the Japanese efforts to incorporate the PRC into a regional order. In contrast, Japanese security relations with the PRC remained tense. They moved from an open containment position to a hard balancing position inside the balancing zone in the later years of the Abe administration. However, economic relations with Beijing were again increasingly marked by economic pragmatism deeply settled in the hedging zone.

Conclusion: Japan Beyond Abe

In a nutshell, Japanese foreign policy has moved from economic preferences and trying to find a binding engagement in economic relations with the PRC in the early years of the DPJ rule to a prioritizing of security issues by fully developing an allied alignment to the US, not only in Japanese national defense, but also in the Japan-US security cooperation beyond the borders of Japan. As a result of the Senkaku Island conflict under Abe, at first, the risk of an escalation and open military conflict was not excluded by many pundits and analysts. However, throughout the years in government, the foreign policy of the Abe administration edged toward an economic pragmatism toward Beijing while continuing allied alignment in security questions toward the US.

A proactive foreign policy marked the long period of the Abe government. In the field of security and trade, Japan has been very active. It has not only navigated the double bind of political and economic hedging under the intensifying rivalry between the PRC and the US, but it has also actively ridden the rivalry, trying (with some success) to influence it. However, even Shinzō Abe, with a concentration of power in his hands like no other prime minister before him, still had to act under democratic constraints. The electorate was not fully supportive of his new security policy. To win elections, he had to pay attention to economic issues, which also resulted in a re-rapprochement to the PRC.

One big question remains: how will Japanese security and foreign policy evolve under his successors? The short stay in power of his immediate successor Yoshihide Suga (2020–2021) as Prime Minister indicates that longer terms in office at the head of the Japanese government might not become the norm, which would also diminish the influence of prime ministers in foreign and security policy. The current Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida (since October 2021), has only been in power for one year. Some pundits expected that he might try to improve relationships with the PRC due to economic considerations. However, he is looking into a new security architecture. The new security agreement between Australia, the UK and the US (AUKUS), as well as the continuity of FOIP and QUAD under the current US President Joe Biden (since January 2021), suggests that the room for maneuvering might shrink for Kishida, even if he could remain in office for a long period. Moreover, the Russian invasion in Ukraine has changed the security perceptions in East Asia. Decision-makers and public opinions are taking the risks of a new war in the region through a Chinese attack on Taiwan much more seriously. This became visible during the Tokyo Quad Summit of May 2022, when the US and its allies, Japan Australia, enlisted India in the grand plan to contain China (Moriyasu 2022). In Japan, especially former Prime Minister Abe has been very active in March and April 2022 in the heated public and political discussions on security policy in response to the Russo-Ukrainian War. He proposed that Japan should consider hosting US nuclear weapons on its territory, which would be a breach of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles of not possessing, not producing and not permitting the introduction of nuclear weapons, which had been introduced back in 1971. This proposal will hardly be realized under the current Prime Minister Kishida who rejected it immediately (Nikkei Asia 2022). However, calls from Abe and others that Japan should substantially increase its defense budget to 2% of its GDP have much bigger chances of being realized. Such an expansion of defense spending would mean breaking a taboo in security policy by going far beyond the 1% of GDP limit for the defense budget, which has been implicit rule for decades in Japan to honor Article 9. Still, this far-reaching proposal finds in view of the war in Ukraine the support of Japan’s population. In a poll in April 2022, 55% of the respondents welcomed such an increase in defense spending and only 33% opposed it (Okuyama 2022). The Chinese non-condemnation of the Russian invasion in Ukraine has reinforced the perception of the PRC as a security threat for Japan and East Asia among Japan’s conservative establishment and its population. Kishida is surely less hawkish than Abe regarding security policy, but for the time being, even after Abe’s assassination in early July 2022, he has limited possibilities for fundamentally deviating from the Abe doctrine, which means maintaining a comprehensive security policy and active support of Taiwan by Japan alongside the US.

Literature

Abe, Shinzō. 2016. Address by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the opening session of the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD VI). August 27. https://www.mofa.go.jp/afr/af2/page4e_000496.html [November 29, 2021].

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2018. The Abe doctrine: Japan’s proactive pacifism and security strategy. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Asō, Tarō. 2006. Arc of Freedom and Prosperity: Japan’s expanding diplomatic horizons. Speech at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, November 30. https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/fm/aso/speech0611.html [November 29, 2021].

Banno, Junji, and Jirō Yamaguchi. 2014. Rekishi o kurikaesu na [Do not repeat history]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Bloomfield, Alan. 2016. To balance or to bandwagon? Adjusting to China’s rise during Australia’s Rudd-Gillard era. The Pacific Review 29 (2): 259–282.

Calder, Kent E. 1988. Japanese foreign economic policy formation: Explaining the reactive state. World Politics 40 (4): 517–541.

Carlson, Matthew. 2020. Sontaku and political scandals in Japan. Public Administration and Policy 23 (1): 33–46.

Chiavacci, David. 2007. The social basis of developmental capitalism in Japan: From postwar mobilization to current stress symptoms and future disintegration. Asian Business and Management 6 (1): 35–55.

Chiavacci, David. 2010. Divided society model and social cleavages in Japanese politics: No alignment by social class, but dealignment of rural-urban split. Contemporary Japan 22 (1/2): 47–74.

Chiavacci, David. 2018. Changing industrial hegemony: Circulation of management ideas between Japan and the West. Asia and Europe – Interconnected: Agents, concepts, and things, ed. Angelika Malinar, and Simone Müller, pp. 15–54. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Chiavacci, David. 2021. Japan’s melting core: Social frames and political crisis narratives of rising inequalities. Crisis narratives, institutional change and transformation of the Japanese state, ed. Sebastian Maslow, and Christian Wirth, pp. 25–50. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Chiavacci, David. 2022. Social inequality in Japan. Oxford handbook of Japanese politics, ed. Robert Pekkanen, and Saadia M. Pekkanen, pp. 451–470. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chiavacci, David, and Julia Obinger. 2018. Towards a new protest cycle in contemporary Japan? The resurgence of social movements and confrontational political activism in historical perspective. Social movements and political activism in contemporary Japan: Re-emerging from invisibility, ed. David Chiavacci, and Julia Obinger, pp. 1–23. London: Routledge.

Chiavacci, David, and Simona Grano. 2020. A new era of civil society and state in East Asian democracies. Civil society and the state in democratic East Asia: Between entanglement and contention in post high growth, ed. David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger, pp. 9–30. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Endo, Masahisa, Robert Pekkanen, and Steven R. Reed. 2013. The LDP’s path back to power. Japan decides 2012: The Japanese general election, ed. Robert Pekkanen, Steven R. Reed, and Ethan Scheiner, pp. 49–64. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Funabashi, Yoichi, ed. 2018. Japan’s population implosion: The 50 million shock. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Funabashi, Yoichi, and G. John Ikenberry, eds. 2020. The crisis of liberal internationalism: Japan and the world order. Washington: Brooking Institution Press.

George Mulgan, Aurelia. 2018. The Abe administration and the rise of the Prime Ministerial executive. London: Routledge.

Hosoya, Yuichi. 2011. The rise and fall of Japan’s grand strategy: The ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’ and the future Asian order. Asia-Pacific Review 18 (1): 13–24.

Hosoya, Yuichi. 2019. FOIP 2.0: The evolution of Japan’s free and open indo-Pacific strategy. Asia-Pacific Review 26 (1): 18–28.

Hughes, Christopher W. 2015. Japan’s foreign and security policy under the ‘Abe Doctrine’: New dynamism or new dead end? New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Iio, Jun. 2019. Seisaku no shitsu to kanryōsei no yakuwari: Abe Naikaku ni okeru ‘kantei shudō’ o rei ni shite [The quality of legislation and the role of the bureaucracy: On the example of ‘leadership by the Prime Minister Office’ under the Abe government]. Nenpō Gyōsei Kenkyū, 54: 2–20.

Ishiba, Shigeki. 2017. Kenpō kyūjō kaisei no jōken [Conditions for amending Article 9 of the constitution]. Bungei shunjū opinion: Ronten 100, ed. Bungei Shunjū Henshubu, pp. 20–23. Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū.

Ishihara, Shintarō. 2013. Nichū yūkō ‘nise’ to ‘gensō’ no 40-nen ha owatta [40 Years of friendship between Japan and China as ‘deception’ and ‘illusion’]. 2013-nen no Ronten 100, ed. Bungei Shunjū, pp. 18–22. Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū.

Kapur, Nicki. 2018. Japan at the crossroads: Conflict and compromise after Anpo. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Katada, Saori N., and Gabrielle Cheung. 2018. Monetary and fiscal politics in the 2017 snap election. Japan decides 2017: The Japanese general election, eds. Robert J. Pekkanen, Steven R. Reed, Ethan Scheiner, and Daniel M. Smith, pp. 243–259. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kingston, Jeff, ed. 2017. Press freedom in contemporary Japan. London: Routledge.

Koga, Kei. 2018. The concept of ‘hedging’ revisited: The case of Japan’s foreign policy strategy in east Asia’s power shift. International Studies Review 20 (4): 633–660.

Koga, Kei. 2020. Japan’s ‘Indo-Pacific’ question: Countering China or shaping a new regional order? International Affairs 96 (1): 49–73.

Kokubu, Takashi. 2015. Abe seiken ha kaishaku kaiken kara meibun kaiken ni mukau ka [Is the Abe administration going from constitutional interpretation amendment to clear constitutional amendment?]. Asahi Shinbun Opinion: Nihon ga Wakaru Ronten 2016, ed. Asahi Shinbun Shuppan, pp. 69–84. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbun Shuppan.

Kolmaš, Michal. 2018. National identity and Japanese revisionism: Abe Shinzo’s vision of a beautiful Japan and its limits. London: Routledge.

Krauss, Ellis S. 2003. The US, Japan, and trade liberalization: Form bilateralism to regional multilateralism to regionalism+. The Pacific Review 16 (3): 307–329.

Kuik, Cheng-Chwee. 2008. The essence of hedging: Malaysia and Singapore’s response to a rising China. Contemporary Southeast Asia 30 (2): 159–185.

Liff, Adam P. 2019. Unambivalent alignment: Japan’s China strategy, the US alliance, and the ‘hedging’ fallacy. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 19 (3): 453–491.

Manicom, James. 2010. Japan’s ocean policy: Still the reactive state? Pacific Affairs 83 (2): 307–326.

Michishita, Narushige, and Richard J. Samuels. 2012. Hugging and hedging: Japanese grand strategy in the 21st century. Worldviews of aspiring powers: Domestic foreign policy debates in China, India, Iran, Japan, and Russia, ed. Henry R. Nau and Deepa M. Olapally, pp. 146–180. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moriyasu, Ken. 2022. Abe leads charge for Japan to boost defense spending to 2% of GDP. Nikkei Asia, April 22, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/Abe-leads-charge-for-Japan-to-boost-defense-spending-to-2-of-GDP [April 27, 2022].

Nihon Keizai Shinbun. 2013. “Himitsu hogo, hantai 5-wari” [Secret protection, 50% against]. November 25, morning edition, p. 1

Nikkei Asia. 2022. Kishida says Japan won’t seek nuclear sharing with U.S.: Prime Minister rejects deterrent idea amid Russian invasion of Ukraine. February 28, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Kishida-says-Japan-won-t-seek-nuclear-sharing-with-U.S [April 27, 2022].

Okuyama, Miki. 2022. Kishida’s handling of inflation spurned by majority: Poll. Asian Nikkei, April 25, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Kishida-s-handling-of-inflation-spurned-by-majority-poll [April 27, 2022].

Ozawa, Ichirō. 1993. Nihon kaizō keikaku [Blueprint for Japan]. Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Pekkanen, Robert J., and Steven R. Reed. 2018. The opposition: From third party back to third force. Japan decides 2017: The Japanese general election, ed. Robert J. Pekkanen, Steven R. Reed, Ethan Scheiner and Daniel M. Smith, pp. 77–92. Houndmills. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pekkanen, Robert J., Steven R. Reed, and Ethan Scheiner, eds. 2013. Japan decides 2012: The Japanese general election. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pyle, Kenneth B. 1992. The Japanese question: Power and purpose in a new era. Washington: AEI Press.

Sakaki, Alexandra, and Sebastian Maslow. 2020. Japan’s new arms export policies: Strategic aspirations and domestic constraints. Australian Journal of International Affairs 74 (6): 649–669.

Sakakibara, Eisuke. 2008. Seiken kōtai [Regime change]. Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū.

Samuels, Richard J. 2007. Securing Japan: The current discourse. Journal of Japanese Studies 33 (1): 125–152.

Saruya, Hiroe. 2021. Rokujūnen Anpo tōsō to chishiki hito - gakusei - rōdōsha: Shakai undō no rekishi shakaigaku [1960s Anpo struggle and intellectuals/students/workers: Historical sociology of social movements]. Tokyo: Shinyōsha.

Satake, Tomohiko, and Ryo Sahashi. 2021. The rise of China and Japan’s ‘Vision’ for free and open indo-Pacific. Journal of Contemporary China 30 (127): 18–35.

Shibata, Saori. 2017. Re-packaging old policies? ‘Abenomics’ and the lack of an alternative growth model for Japan’s political economy. Japan Forum 29 (3): 399–422.

Shinoda, Tomohito. 2005. Japan’s cabinet secretariat and its emergence as core executive. Asian Survey 45 (5): 800–821.

Shinoda, Tomohito. 2013. Contemporary Japanese politics: Institutional changes and power shifts. New York: Columbia University Press.

Shiratori, Hiroshi (ed.). 2010. Seiken kōtai senkyo no seijigaku: Chihō kara kawaru Nihon seiji [Political science of the change of governmen election: The countryside changing Japanese politics]. Kyoto: Mineruva Shobō.

Smith, Sheila A. 2015. Intimate rivals: Japanese domestic politics and a rising China. New York: Columbia University Press.

Soble, Jonathan. 2015. Japan moves to allow military combat for first time in 70 years. The New York Times, July 17, p. A1.

Solís, Mireya. 2020. Follower no more? Japan’s leadership role as a champion of the liberal trading order. The crisis of liberal internationalism: Japan and the world order, ed. Funabashi, Yoichi, and G. John Ikenberry, pp. 79–105. Washington: Brooking Institution Press.

Solís, Mireya, and Shujiro Urata. 2018. Abenomics and Japan’s trade policy in a new era. Asian Economic Policy Review 13 (1): 106–123.

Stockwin, J.A.A. 1962. ’Positive neutrality’: The foreign policy of the Japanese socialist party. Asian Survey 2 (9): 33–41.

Suzuki, Miho. 2013. “Mainichi shinbun seron chōsa: Himitsu hogo hōan ‘hantai’ 59-pāsento” [Mainichi newspaper opinion poll: Secret protection bill ‘opposite’ 59%]. Mainichi Shinbun, morning edition, p. 1, November 12.

Suzuki, Shogo, and Corey Wallace. 2018. Explaining Japan’s response to geopolitical vulnerability. International Affairs 94 (4): 711–734.

Takeda, Hiroko. 2018. Between reproduction and production: Womenomics and the Japanese government’s approach to women and gender policies. Jendā Kenkyū 21: 49–70.

Takenaka, Harukata. 2019. Expansion of the Prime Minister’s power in the Japanese parliamentary system: Transformation of Japanese politics and institutional reforms. Asian Survey 59 (5): 844–869.

Tanaka, Hideaki. 2019. Japan’s problematic administrative reform: A plea for neutral policymaking. Nippon.com, October 18, https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/d00516/japan%E2%80%99s-problematic-administrative-reform-a-plea-for-neutral-policymaking.html [December 3, 2021].

Tashiro, Yōichi. 2013. Abe seiken to TPP: Sono seiji to keizai [The Abe administration and the TPP: Its politics and economics]. Tokyo: Tsukaba Shobō.

The Economist. 2012. China and Japan: Could Asia really go to war over these. September 22–29, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2012/09/22/could-asia-really-go-to-war-over-these [December 3, 2021].

Tsai, Hsi-Hsum. 2012. Nihon fukkatsu no daisenryaku: Sandome no kiseki ha okiru no ka? [Grand strategy for Japan’s revival: Will a third miracle occur?]. Taipeh: Zhiliang Publishing House.

Urata, Shujiro. 2020. US-Japan trade frictions: The past, the present, and implications for the US-China trade war. Asian Economic Policy Review 15 (1): 141–159.

Williams, Brad. 2013. Japan’s evolving national security secrecy system: Catalysts and obstacles. Pacific Affairs 86 (3): 493–513.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chiavacci, D. (2023). Navigating and Riding the Double Bind of Economic and Political Hedging: Japan and the US-China Strategic Competition. In: Grano, S.A., Huang, D.W.F. (eds) China-US Competition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15389-1_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15389-1_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15388-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15389-1

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)