Abstract

Among Hispanic women, breast cancer is the most common cancer accounting for close to 30% of the total cancer cases. It is estimated that in 2018 alone, 24,000 Hispanics were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Of significant importance is that breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death (16%) among Hispanic women, with over 3000 patients dying in 2018 secondary to this disease.

Despite the decrease in breast cancer mortality rates seen in recent years, the magnitude of that decrease among Hispanics is lower compared to the decrease seen among non-Hispanic White women (1.1% per year vs 1.8% per year). Potential contributing factors associated with this phenomenon include the fact that Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced stages and to have tumors with aggressive biology. In addition, sociodemographic factors and difficulty accessing medical care are likely to play an important role. It has been described that Hispanic women are less likely that non-Hispanic Whites to receive appropriate and timely breast cancer treatment. In this chapter, we will review the complexities of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. We will briefly review some of the challenges in cancer care delivery that Hispanics experience and will review data describing the detrimental impact that treatment delays can have among minorities and some of the unique challenges that Hispanics experience.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide [1]. In the United States, it also represents the most common cancer in women – in 2019, it is estimated that 268,600 women were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and 41,760 died of the disease. Among Hispanic women, breast cancer is the most common cancer accounting for close to 30% of the total cancer cases. It is estimated that in 2018 alone, 24,000 Hispanics were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer [2]. Of significant importance is that breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death (16%) among Hispanic women, with over 3000 patients dying in 2018 secondary to this disease [2].

Despite the decrease in breast cancer mortality rates seen in recent years, the magnitude of that decrease among Hispanics is lower compared to the decrease seen among non-Hispanic White women [3]. Potential contributing factors associated with this phenomenon include the fact that Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced stages and to have tumors with aggressive biology. In addition, sociodemographic factors and difficulty accessing medical care are likely to play an important role. It has been described that Hispanic women are less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to receive appropriate and timely breast cancer treatment [4]. Unfortunately, cancer care delivery is not the same for all and this can seriously hinder the cancer outcomes of those affected. In this chapter, we will discuss the complexities associated with breast cancer treatment and some of the challenges in cancer care delivery that Hispanics experience. In addition, we will expand on data describing the detrimental impact that treatment delays can have among minorities and some of the unique challenges that Hispanics experience.

Understanding the Magnitude of the Problem: Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the deadliest cancer among women worldwide, with a total of over half a million deaths annually impacting both developed and developing countries [1]. There are an estimated 912,930 new cancer cases expected to occur in the United States in 2020 – breast cancer alone is projected to account for 30% of these cases despite numbers accounting solely for cases among women. With an estimated 276,480 breast cancer cases projected to occur in women, it is estimated that 42,170 women will die in 2020 due to this devastating disease [5].

Currently, one in eight women in the United States are likely to develop breast cancer in their lifetime [5]. While a decrease in breast cancer incidence is being seen overall due to continued screening efforts and therapeutic improvements, this trend is disparate across race and ethnicity. Hispanics make up the largest minority group in the United States with a population that is expected to double over the next four decades [2]. Although Hispanic women experience lower breast cancer incidence compared to Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites (93.9, 126.7, and 130.8 per 100,000, respectively) [5], the projected population growth coupled with increasing lifestyle risk factors through acculturation could contribute to a higher breast cancer incidence and mortality overall.

Breast Cancer Outcomes in Minorities: Why the Difference?

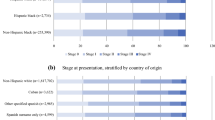

Despite minority groups having lower rates of breast cancer incidence among women, Black and Hispanic women are more likely to: (1) be diagnosed with more aggressive forms of breast cancer [4], (2) experience higher rates of delays in breast cancer treatment, and (3) have worse survival outcomes compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts [4, 6]. In order to better explain the differences in breast cancer outcomes among minorities, we must analyze this phenomenon through the complex interaction of social, cultural, and structural factors between minorities and the health-care system.

One of the cornerstones of breast cancer control is early detection of abnormalities to improve outcomes and survival – yet there are significant differences in adherence to screening guidelines among Hispanic, Black, and non-Hispanic White women, with foreign-born women being less likely to have ever had a mammogram [7, 8]. According to the last mammography utilization rates reported by the Center for Disease Control in 2015, Black and non-Hispanic White women both have higher breast cancer screening rates (69.7% and 65.8%, respectively) than Hispanics (60.9%), reported as the percent of women having had a mammogram in the last 2 years [9]. The disparity in screening among foreign-born women compared to US-born women is even greater (88.3% compared to 94.1%), with even lower rates of screening among recently immigrated women (76.4%) [8].

Hispanics in particular are more likely to not adhere to screening guidelines, be diagnosed with advanced stages of disease, have longer time to definitive diagnosis and treatment initiation, and experience poorer quality of life relative to non-Hispanic Whites [3]. Inequities in cancer and quality of life outcomes are impacted by intermediate and modifiable targets that act as barriers to accessing breast cancer treatment, including but not limited to psychosocial, health care, cancer-specific, medical factors, and cultural factors [10].

It has been reported that foreign-born minorities experience a unique process of acculturation in regard to American culture and lifestyle [10, 11]. Acculturation is a multidimensional process of culture change among Hispanics through integration of cultural values and habits of their surrounding social environment relative to their native culture. Interestingly, studies have revealed that acculturation carries both positive and negative impacts on health outcomes.

Benefits of acculturation can encompass an increase in English literacy and the ability to communicate with health-care providers as well as a shift in cultural perspectives of susceptibility to disease, all of which can increase breast cancer screening among Hispanic women. However, acculturation can also have detrimental impacts on breast cancer outcomes among Hispanics by assumption of lifestyle behaviors similar to those of American women which has been studied as a possible factor in the stagnancy of decreasing incidence rates among Hispanic women beyond nonadherence to screening [6, 10].

Foreign-born Hispanics experience a unique protective benefit from a combination of their native values and lifestyle factors, a phenomenon referred to as the Hispanic paradox [10, 12]. The Hispanic paradox emerged from observations showing that middle-aged to elderly Hispanics had similar or improved mortality compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts [13]. This immigrant paradox highlights the negative impacts of acculturation on foreign-born Hispanic’s health outcomes. The Hispanic paradox suggests significant correlations between varying levels of American acculturation, socioeconomic factors, and native cultural factors influencing health statuses [12]. Recent research suggests that the benefits from the Hispanic paradox may also carry over to cancer outcomes [10].

Is Breast Cancer Care Delivery Equal for All?

Breast Cancer Treatment, Biology, and Social Factors

Today, a large proportion of patients with early-stage breast cancer are cured due to the high effectiveness of breast cancer treatment. Breast cancer treatment by nature is multidisciplinary and most patients receive multi-modality treatment, usually including surgery, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and endocrine therapy) [3]. The complex, and in many cases long, treatments that are needed to achieve the desired outcomes force patients to face issues associated with navigating the health-care system, timely treatment, and adherence.

It is well known that breast cancer is a biologically heterogenous disease. While it is possible that some biological features are different among Hispanic populations, many cancer-specific biological factors are not well studied in Hispanic populations [10]. Evaluating biological or molecular characteristics of cancer in Hispanics is inherently challenging, given the great heterogeneity and diversity that defines Hispanics and Latinx populations. Despite this, our group and many others have tried to determine whether the differences in outcomes seen among Hispanics can be explained based on biological factors alone.

In a study evaluating 2074 breast cancer patients treated with similar preoperative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy regimens, we determined that after adjusting for breast cancer subtype, the rates of complete pathological response were not different among Hispanics, suggesting that treatment effect is not associated with race or ethnicity [14]. Similarly, using transcriptional profiling in a cohort of 376 breast cancer patients, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of protein expression data showed no distinct clusters by race. An analysis of patients registered to participate in phase II/III clinical trials showed that when Hispanic breast cancer patients receive uniform treatment and follow-up in a highly controlled setting, no differences in survival are observed when compared to non-Hispanics [15]. This study emphasizes that when Hispanic cancer patients receive state-of-the-art treatment, disparate outcomes among race and ethnicity groups are reduced. The evidence described above suggests that differential outcomes are not derived from differences in biology or differential treatment, but rather that social determinants of health are at the root of the problem.

Social determinants of health encompass a complex interplay of factors. The place where an individual lives, learns, and works influences a wide range of health decisions, risks, and both quality-of-life and health outcomes [16]. Among some Hispanics, issues like lower rates of economic stability, language differences, low health literacy, and lack of access to regular medical services and/or health insurance determine poor health outcomes [17]. For Hispanic women, some of these social determinants and their interconnections are shown in Fig. 6.1, which graphically depicts how all these factors can have a critical impact on breast cancer outcomes.

Ideally, the first steps in cancer care include prevention and early detection. Breast cancer screening programs are aimed at evaluating healthy women prior to the presentation of symptoms to detect abnormalities at an early stage. Hispanic women tend to have low screening rates, a phenomenon has been connected to cultural factors, financial factors, and limited access to health care [10, 18]. Given the low participation rates in screening programs, many Hispanic women begin their breast cancer journey after symptoms have presented, most commonly the detection of a palpable mass [6]. The difference between screening and diagnosis based on symptoms can have a significant impact on cancer outcomes, as presentation of symptoms can indicate breast cancer that has progressed to a more advanced stage. Advanced presentation of cancer is not confined to older Hispanic women, as younger Hispanic women tend to experience diagnostic delays due to providers’ lack of suspicion of cancer at first presentation [19]. Suboptimal cancer care disproportionately impacts Hispanic patients throughout the continuum of breast cancer treatments [20].

The Impact of Treatment Delays

Treatment delays have been known to have significant detrimental impacts on survival outcomes among vulnerable populations [10, 21,22,23]. Shortened times to surgery along with timely initiation and administration of treatment can be a turning point for survival outcomes [24] – yet treatment delays persist. Hispanic women’s disparate experience with cancer care does not stop at screening nonadherence or diagnostic delays – longer times to surgery from diagnosis and delays in chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and endocrine therapy have all been found to be significantly different among Hispanic women. One study focusing on breast cancer patients in a safety net hospital observed 3.38 times increased odds of longer interval between initial presentation of symptoms and first treatment among patients with Hispanic ethnicity compared to non-Hispanic Whites [20].

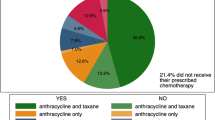

Adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation, and endocrine therapy dramatically decrease the risk of breast cancer recurrence and breast cancer mortality. However, evidence suggests significant delays in administration across race and ethnicity and across those belonging to a low socioeconomic status [25,26,27]. Significant delays in initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy have been found to have adverse breast cancer outcomes [21,22,23]. Research from our group demonstrated that older age, Hispanic ethnicity, and non-Hispanic Black race as well as low socioeconomic status are all associated with treatment delays. Other factors that have been associated to delays include comorbidities, not having a partner, being uninsured, and being a Medicare or Medicaid beneficiary. Treatment delays likely contributed to Hispanic breast cancer patients having 1.53 higher risk of experiencing worse overall survival and 1.27 higher risk of worse breast-cancer specific survival compared to Whites [21,22,23].

Since patients that experience delays in the administration of chemotherapy are at an increased risk of death, every effort should be made to understand and remove barriers associated with treatment delays. However, in order to fully understand this complex phenomenon, it is imperative to evaluate factors at the operational, medical, and personal/social level. Our group is currently recruiting participants to project START (NCT04087057), a qualitative study in which we aim to comprehensively assess and identify determinants of delays in chemotherapy initiation among breast cancer patients. In addition to deeply evaluating operational and personal factors, we are evaluating social support, health literacy, and trust in medical professionals using validated instruments. We believe that understanding the complexities of the problem at hand is critical in the design and implementation of highly effective strategies for decreasing treatment delays.

Impact of COVID-19

In 2020, the global health-care system was overwhelmed by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization. As of September 2020, the global health crisis had seen over three million cases of COVID-19 caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with almost one million fatalities [28].

Since the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in the United States, screening tests for early detection of cervical, breast, and colon cancer plummeted by over 85% [29]. It is estimated that 79% of cancer patients actively undergoing treatment experienced some type of a delay in care due to COVID-19, with 17% specifically experiencing a delay in cancer therapy (chemotherapy, radiation, endocrine therapy) [30]. Communities of color and minorities have disproportionately shouldered the COVID-19 burden, with Hispanics accounting for 34% of cases despite only representing 18% of the US population [31] – this unequal burden exacerbates the poor survival outcomes among Hispanic women with cancer as they are at higher risk for mortality if infected with SARS-CoV-2 than non-cancer patients [29]. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 among cancer patients and minorities is yet to be determined; however, the National Cancer Institute estimates an additional 10,000 associated deaths from breast cancer and colorectal cancers over the next decade due to the global pandemic’s impact on screening and treatment [32].

How to Improve Cancer Care Delivery for All?

Success in improving cancer care delivery for all hinges on a holistic approach to reducing disparities across race, ethnicity, and the socioeconomic strata. Increasing adherence to screening guidelines for early detection is critical for overall improvement in survival outcomes, but we cannot ignore the complex dynamics of factors that infringe on cancer care access among minorities. Expansion of culturally effective health education programs and social assistance alongside research of biological differences in Hispanic tumor characteristics are crucial in improving cancer care delivery and long-term breast cancer outcomes.

Patient navigation programs are known to play a role in reducing cancer disparities by empowering patients to take an active role in their health-care experience – this is accomplished by the use of patient navigators, people who work with patients to eliminate barriers to accessing care once they are admitted into the health-care system [3]. Traditional patient navigation only comes into play when an individual has been admitted into the health-care system with the intention to decrease delays in treatment initiation and delivery with little to no impact on adherence to timely screening. Community patient navigation can bridge the gap between the community and clinical setting by expanding the traditional patient navigation program beyond the existing internal system within the health care. The implementation of community-based navigation programs among Hispanics, such as Naveguemos con Salud in Philadelphia, extends social assistance to target individuals from prescreening outreach to posttreatment follow-up [18] in order to improve quality of life and outcomes among Hispanics [10]. This form of community planning highlights the need for culturally sensitive health education programming and implementation, which can successfully address cultural factors contributing to screening nonadherence by targeting not just Hispanic women but also their family units and supporting communities.

Increasing access and availability of financial assistance programs for minorities along with expanding eligibility criteria is key in reducing financial toxicity derived from breast cancer treatment and care. Financial assistance programs provide additional support to mitigate treatment costs, yet limited assistance programs exist to cover family expenses, cost of living, or indirect medical costs, such as housing and travel [26]. There are a number of theoretical models showing that Hispanic breast cancer patients tend to emphasize survival at any cost over financial concerns; however, resulting financial stress from limited pretreatment knowledge and delays in financial planning have long-lasting impact even beyond post-cancer treatment [26].

Further investigation of the differences among Hispanic subgroups in regard to cultural differences and their impact on health decision-making and education is necessary to develop increasingly culturally effective health education interventions to reduce breast cancer disparities. Quantitative research provides insight into the treatment delays among women with breast cancer by identifying key factors that elucidate the complex interaction of social determinants of health. Future research should focus on expanding breast cancer patient narratives to enrich qualitative understanding of treatment delays among racial and ethnic populations to develop a culturally effective framework for reducing health disparities and improving breast cancer outcomes for all.

References

World Health Organization. WHO | Breast cancer. WHO; 2018.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2018–2020. Atlanta; 2018.

American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2019–2020. Am Cancer Soc. 2019.

Farias AJ, Wu WH, Du XL. Racial differences in long-term adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence and mortality among Medicaid-insured breast cancer patients in Texas: findings from TCR-Medicaid linked data. BMC Cancer [Internet]. 2018 Dec 4 [cited 2020 Sep 20];18(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6280479/?report=abstract.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];70(1):7–30. Available from: https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21590.

Miller BC, Bowers JM, Payne JB, Moyer A. Barriers to mammography screening among racial and ethnic minority women. Soc Sci Med. Elsevier Ltd. 2019;239:112494.

Bolton CD, Sunil TS, Hurd T, Guerra H. Hispanic men and women’s knowledge, beliefs, perceived susceptibility, and barriers to clinical breast examination and mammography practices in South Texas Colonias. J Community Health [Internet]. 2019 Dec 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];44(6):1069–75. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31161398/

Clarke TC, Duran D, Saraiya M. Breast cancer screening among women by nativity, birthplace, and length of time in the United States [Internet]. Vol. 129. National Health Statistics Reports Number; 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm.

Center for Health Statistics N. Health, United States 2018 Chartbook [Internet]. Health. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/hus_infographic.htm.

Yanez B, McGinty HL, Buitrago D, Ramirez AG, Penedo FJ. Cancer outcomes in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: an integrative review and conceptual model of determinants of health. J Lat Psychol [Internet]. 2016 May [cited 2020 Sep 20];4(2):114–29. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4943845/?report=abstract.

John EM, Phipps AI, Davis A, Koo J. Migration history, acculturation, and breast cancer risk in Hispanic women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2005 Dec 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];14(12):2905–13. Available from: https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/14/12/2905.

Teruya SA, Bazargan-Hejazi S. The immigrant and Hispanic paradoxes: a systematic review of their predictions and effects. Hisp J Behav Sci [Internet]. 2013 Nov 5 [cited 2020 Sep 19];35(4):486–509. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0739986313499004.

Turra CM, Goldman N. Socioeconomic differences in mortality among U.S. adults: insights into the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci [Internet]. 2007 May 1 [cited 2020 Sep 19];62(3):S184–92. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/62/3/S184/600844.

Chavez-MacGregor M, Litton J, Chen H, Giordano SH, Hudis CA, Wolff AC, et al. Pathologic complete response in breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline- and taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy: evaluating the effect of race/ethnicity. Cancer [Internet]. 2010 Sep 1 [cited 2020 Sep 23];116(17):4168–77. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20564153/.

Chavez-MacGregor M, Unger JM, Moseley A, Ramsey SD, Hershman DL. Survival by Hispanic ethnicity among patients with cancer participating in SWOG clinical trials. Cancer. 2018;124(8):1760–9.

Social Determinants of Health | Healthy People 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health.

Karimi SE, Rafiey H, Sajjadi H, Nejad FN. Identifying the social determinants of breast health behavior: a qualitative content analysis. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev [Internet]. 2018 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];19(7):1867–77. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6165651/?report=abstract.

Keith JD, Kang NE, Bodden MR, Miller C, Karamanian V, Banks T. Supporting Latina breast health with community-based navigation. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. 2019 Aug 15 [cited 2020 Sep 20];34(4):654–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29574540/.

Unger-Saldaña K, Fitch-Picos K, Villarreal-Garza C. Breast cancer diagnostic delays among young Mexican women are associated with a lack of suspicion by health care providers at first presentation. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–12.

Jaiswal K, Hull M, Furniss AL, Doyle R, Gayou N, Bayliss E. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: a safety-net population profile. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];16(12):1451–7. Available from: https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/16/12/article-p1451.xml.

Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajn DY, Giordano SH. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):322–9.

Smith-Graziani D, Lei X, Giordano SH, Zhao H, Karuturi M, Chavez-MacGregor M. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2020;9(19):6961–71.

De Melo Gagliato D, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lei X, Theriault RL, Giordano SH, Valero V, et al. Clinical impact of delaying initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):735–44.

Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Beck JR, Ross E, Wong YN, et al. Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2016 Mar 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];2(3):330–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26659430/.

Rossi L, Stevens D, Pierga J-Y, Lerebours F, Reyal F, Robain M, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on breast cancer survival: a real-world population. Bathen TF, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015 Jul 27 [cited 2020 Sep 20];10(7):e0132853. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132853.

Chebli P, Lemus J, Avila C, Peña K, Mariscal B, Merlos S, et al. Multilevel determinants of financial toxicity in breast cancer care: perspectives of healthcare professionals and Latina survivors. Support Care Cancer [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];28(7):3179–88. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31712953/.

Wöckel A, Wolters R, Wiegel T, Novopashenny I, Janni W, Kreienberg R, et al. The impact of adjuvant radiotherapy on the survival of primary breast cancer patients: a retrospective multicenter cohort study of 8935 subjects. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2014 Mar 1 [cited 2020 Sep 20];25(3):628–32. Available from: http://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923753419342760/fulltext.

WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

AACR cancer disparities progress report 2020 | Cancer Progress Report [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 19]. Available from: https://cancerprogressreport.aacr.org/disparities/.

COVID-19 pandemic ongoing impact on cancer patients and survivors survey findings summary [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/.

COVID-19 data from the National Center for Health Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/index.htm.

Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer [Internet]. Vol. 368. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 20]. p. 1290. Available from: www.cancer.gov.

Acknowledgments

MCM is funded by Susan G. Komen, CIPRIT, Conquer Cancer and BCRF. CM is funded by Susan G. Komen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Malinowski, C., Chavez Mac Gregor, M. (2023). Cancer Care Delivery Among Breast Cancer Patients: Is it the Same for All?. In: Ramirez, A.G., Trapido, E.J. (eds) Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14436-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14436-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14435-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14436-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)