Abstract

Over the last several decades, the survival for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has increased from about 40–90%. However, current treatment strategies are associated with several acute and long-term toxicities, including neurotoxicity. Further, racial and ethnic disparities persist in both incidence and outcomes for ALL. In particular, Latino children experience both the highest incidence of ALL and less favorable outcomes. The incidence of neurotoxicity during ALL therapy potentially jeopardizes treatment efficacy, and long-term neurocognitive impairment profoundly affects quality of life for survivors. Emerging evidence indicates that Latino patients may be particularly susceptible to these adverse side effects of therapy. Unfortunately, studies of neurotoxicity during ALL therapy have not included large populations of Latino children. Therefore, well-designed studies are needed to characterize neurotoxicity outcomes in Latino patients, while considering factors associated with disparities in cognitive performance in the general population, including socioeconomic status and acculturation. Ultimately, a better understanding of the various factors likely responsible for disparities in neurotoxicity is needed to improve outcomes for Latino children with ALL; these factors include inherited genetic variation, clinical characteristics, and sociocultural differences.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignancy diagnosed during childhood [1]. Once considered a terminal diagnosis, pediatric ALL is now curable in approximately 90% of cases with contemporary therapy [2]. Despite significant improvements in the treatment of pediatric ALL, racial and ethnic disparities still persist. In particular, compared to non-Latino White populations, Latinos have both a higher incidence of pediatric ALL and less favorable outcomes [3]. Disparities in pediatric ALL outcomes are likely due to a number of factors, including ethnic variability in somatic molecular profiles, comorbidities, treatment adherence, and response to chemotherapy. Notably, exposure to central nervous system (CNS)-directed chemotherapy during ALL treatment is associated with a risk of acute and long-term neurotoxicity [4, 5]. Emerging research from our group and others suggests Latino patients with ALL may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse neurologic side effects of CNS-directed therapy [6,7,8]. Therefore, we provide an overview of ethnic disparities in treatment-related neurotoxicity and recommendations for future research directions.

Acute Neurotoxicity During ALL Therapy

The antifolate agent methotrexate is an important component of contemporary curative pediatric ALL protocols. Current ALL chemotherapy regimens typically include intravenous (IV), intrathecal (IT), and oral methotrexate. The antineoplastic effects of methotrexate are attributed to the competitive inhibition of the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzyme involved in tetrahydrofolate synthesis. The resulting tetrahydrofolate deficiency disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis, leading to cell cycle arrest. Methotrexate preferentially inhibits rapidly dividing cells, such as leukemic cells. However, because methotrexate is a folic acid analogue, prolonged use or exposure to high doses of methotrexate may deplete folate stores and result in adverse side effects. Specifically, approximately 10% of pediatric patients with ALL experience acute or subacute neurotoxicity, typically occurring within 14 days of receiving CNS-directed high-dose IV or IT methotrexate [4, 5]. Acute and subacute methotrexate-related neurotoxicity often manifests clinically as a combination of seizure, aphasia, altered mental status, stroke-like symptoms, and encephalopathy [6,7,8]. Although these symptoms are typically transient [9], the clinical management of methotrexate-related neurotoxicity often leads to delays or modification of cancer therapy, potentially limiting treatment efficacy. In fact, recent evidence from our group suggests that patients with suspected neurotoxic events during ALL therapy receive an average of two fewer doses of IT methotrexate [8]. Although follow-up was limited in this cohort, we also observed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) trend toward an increased risk of relapse in patients with a history of methotrexate-related neurotoxicity.

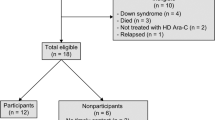

Despite neurotoxicity being a serious complication of methotrexate chemotherapy, information on the factors which modify the risk of methotrexate-related neurotoxicity is limited. Several independent studies have reported associations between older age at diagnosis and treatment intensity and the incidence of acute and subacute neurotoxicity [4, 5, 8, 10]. Recent case series further suggest that susceptibility to methotrexate-related neurotoxicity may vary across racial and ethnic groups. Giordano et al. [7] presented information on five ALL patients with acute or subacute neurotoxicity, all of whom were Latino, while Afshar et al. [6] described the presentation of clinical neurotoxicity in 18 pediatric oncology patients, including 12 Latino cases. Most recently, we conducted one of the largest evaluations of acute and subacute methotrexate-related neurotoxicity in a multisite study of patients treated on recent pediatric ALL protocols [8] and found significant differences in the incidence of neurotoxicity by ethnic group (Fig. 4.1). This analysis of 280 newly diagnosed (between 2012 and 2017) patients found that neurotoxicity occurred in 21.8% of Latino compared to 6.8% of non-Latino patients, corresponding to a nearly 2.5-fold increased risk of neurotoxicity after accounting for other clinical and demographic factors.

Growing evidence supports an association between genome-wide genetic ancestry and racial/ethnic disparities in pediatric ALL outcomes, including relapse [11], suggesting that genetic variants, which impact antileukemia therapy pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, may co-segregate with areas of the genome associated with differing ancestral populations [12]. Because Latino ethnicity encompasses a genetically diverse population with various degrees of European, African, and Native American genetic admixture, we sought to evaluate the association between genetic ancestry and methotrexate-related neurotoxicity in a prospective cohort of pediatric patients with ALL. We estimated the proportions of European, African, East Asian, and Native American genetic ancestry using genome-wide genotype data available on 190 pediatric patients with ALL, including 35 individuals with a history of acute and subacute methotrexate-associated neurotoxicity, and publicly available reference populations [13, 14]. The proportion of genetic variation that co-segregates with Native American ancestry was overrepresented in individuals with methotrexate-related neurotoxicity (mean = 34.9%; Fig. 4.2) compared to individuals without a history of neurotoxicity (mean = 23.2%, p = 0.025). In multivariable proportional hazards regression models accounting for sex, age at diagnosis, and treatment risk group, every 10% increase in the proportion of Native American genetic ancestry was associated with a 16% increase in neurotoxicity incidence (HR = 1.16; 95% CI: 1.02–1.32). These findings highlight that ethnic-specific differences in inherited genetic variation likely contribute to disparities in the incidence of treatment-related toxicity.

Neurocognitive Late Effects of ALL Therapy

Contemporary treatment protocols for childhood ALL have largely eliminated the use of prophylactic cranial radiation in favor of CNS-directed chemotherapy [4, 15, 16]. Efforts to reduce exposure to cranial radiation have also reduced many adverse effects of ALL therapy, including neurocognitive deficits. Although cognitive functioning in survivors treated with contemporary chemotherapy is better preserved than in those treated with cranial radiation, survivors treated with chemotherapy alone continue to demonstrate deficits relative to their unaffected peers [17,18,19,20,21]. In fact, neurocognitive difficulties are estimated to be one of the most prevalent late effects of childhood ALL chemotherapy, affecting nearly 50% of survivors [22]. Neurocognitive difficulties are commonly detected in the domains of attention, executive functioning, working memory, and processing speed among long-term survivors of childhood ALL [17, 23, 24]. Neurocognitive changes in this population appear to be related to the effects of methotrexate, which have been associated with demyelinating white matter injury and vascular damage in the developing brain. Specifically, survivors treated with chemotherapy only have been found to have total white matter volume loss [25], notably in the frontal [26] and subcortical regions [27], and abnormal or reduced white matter connectivity [27,28,29], with children diagnosed at younger ages being particularly vulnerable to these adverse effects of treatment [27]. Children and adolescents experiencing clinical findings of acute or subacute methotrexate neurotoxicity during treatment may be at particularly increased risk for long-term neurocognitive deficits [30]. For example, children who experienced seizures during treatment for ALL demonstrated reduced attention, working memory, and processing speed relative to children who did not develop seizures and had normative scores at the end of treatment; additionally, these difficulties persisted over a two-year follow-up period [30]. However, other therapeutic exposures, including anesthesia, have been associated with persistent neurocognitive issues among survivor [31]. These cognitive deficits not only impede learning and academic achievement but also have long-term educational and economic consequences [32,33,34].

Despite increased incidence of ALL and neurotoxic events during therapy among Latino patients coupled with increased neurocognitive risk among Latinos more broadly, there is an extreme lack of population diversity in neurocognitive outcomes research for pediatric ALL to date. According to recent meta-analyses summarizing sociodemographic factors and neurocognitive outcomes in ALL, only one-third of studies reported the ethnic/racial composition of their sample, and when race/ethnicity was reported, the overwhelming majority (almost 80%) self-identified as White or Caucasian [21, 35]. Two studies have been conducted among Latino cohorts, and they indicate that survivors are at risk for neurocognitive late effects and school-based learning difficulties [36, 37]. Specifically, Latino survivors of pediatric ALL demonstrated reduced performance relative to the normative mean in neurocognitive domains typically affected in non-Latino patients including working memory, processing speed, visual reasoning, executive functioning, and visual learning [37]. In addition, Latino survivors demonstrated reduced verbal reasoning and reading comprehension skills, which are not typically implicated in late effects research of predominantly non-Latino populations. Despite a focus on Latino survivors, models did not account for socioeconomic status (SES), though proxies for the general socioeconomic standing of the sample were described.

Emerging Research Needs

Most models of neurotoxicity in pediatric patients with ALL have focused on clinical predictors, often excluding sociodemographic and molecular factors known to influence neurologic development and outcomes in unaffected populations. For example, neurocognitive abilities of children in the general population are adversely impacted by many factors, including SES and native language [38, 39], which disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities. Despite the fact that ethnic disparities in ALL outcomes and toxicity are well documented [3, 11, 40,41,42,43], few studies have evaluated neurotoxicity in multiethnic populations, much less evaluated the role of SES and acculturation [24, 36, 37, 44]. Moreover, the considerable inter-patient variability in susceptibility to neurotoxicity might be partly explained by underlying molecular variation. However, the role of these factors in treatment-related neurotoxicity has received limited attention. Additional research on the roles of socioeconomic, cultural, and biologic factors in ethnically diverse populations is needed to advance our understanding of neurological outcomes in vulnerable populations.

Incorporating Information on SES and Acculturation

Survivors of childhood ALL who are from racial/ethnic minority groups and lower SES are at increased risk for cognitive deficits. SES refers to a combination of income, education, and occupation [45]. Therefore, generally speaking, the relationship between ethnicity and neurocognitive outcome is complex, given that ethnicity and SES can be highly related, particularly among Latino families [46]. In particular, Latinos who immigrate to the United States have, on average, a lower SES [47], though there is considerable variability depending on country of origin. For example, Cuban-Americans graduate from college at three times the rate of Mexican-Americans [48]. Among healthy children, associations are documented between SES and cognitive abilities. The domains most affected by SES disparities include language abilities, executive functioning, attention, and memory [38, 39]. Overall, few studies have considered SES in relation to neurocognitive outcome among survivors of childhood leukemia; however, when these factors are considered the observed associations are typically consistent with individuals of lower SES having an increased risk of impairment [49].

Among Latino families, acculturation may simultaneously impact cognitive and academic skill development along with socioeconomic factors, though acculturation is not necessarily related to such factors. Language is an important aspect of determining an individual’s level of acculturation. Parent language acculturation in Latino families, namely English proficiency and primary language in the home, is important for children’s academic readiness and academic success in higher grades [50, 51]. Furthermore, Latino children whose native language is Spanish perform significantly worse than non-Latino children on the Wechsler Intelligence Scales, the most commonly used measure of intelligence in childhood, with specific adverse effects exhibited on verbal subtests [52]. While there are a number of proxies for acculturation, such as generational status and number of years of US residency, none of them are adequate for providing insight into the influence on the acculturative experience on neurocognitive development and performance.

Molecular Predictors of Neurotoxicity

In addition to variability in patient characteristics and therapeutic exposures, a number of factors likely contribute to disparities in pediatric ALL toxicity and outcomes, including underlying genetic variation. To date, few studies have evaluated inherited single nucleotide variants; however, associations have been reported between clinical neurotoxicity and candidate variants in SHMT1, MTHFR, and GSTP1 [53, 54]. In particular, the missense C677T polymorphism in MTHFR (rs1801133) has been associated with adverse responses to methotrexate therapy in pediatric and adult patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis and various malignancies [55,56,57]. Several publications have speculated that inherited variation in MTHFR may also contribute to the risk of methotrexate-related neurotoxicity in children with ALL [54, 58], but direct evidence that MTHFR genetic variation affects neurotoxicity susceptibility is limited. Compared to individuals who are homozygous for the reference allele (CC), carriers of the alternate allele (CT/TT) exhibit decreased MTHFR enzymatic activity and increased plasma homocysteine levels [59]. Homocysteine concentrations are transiently elevated following methotrexate therapy, and cerebrospinal fluid levels of homocysteine have been linked to neurotoxicity in children undergoing treatment of ALL [60, 61]. Notably, the frequency of the C677T missense variant appears to vary across ancestral populations. Based on the 1000 Genomes data [62], the C677T alternate allele frequency is approximately 9.0% in individuals of African ancestry, 36.5% in individuals of European ancestry, and 47.0% in admixed American populations comprised individuals of Latino ethnicity. Additional research is needed to better characterize the genetic contribution to methotrexate-related neurotoxicity and disparities in susceptibility. However, genome-wide association studies have not yet successfully identified and replicated susceptibility loci due to challenges in assembling large cohorts to sufficiently power these studies [4]. Alternative approaches that examine the association between local Native American genetic ancestry and neurotoxicity risk using methods such as admixture mapping may prove more powerful at identifying novel susceptibility loci responsible for the ethnic disparities observed in neurotoxicity risk.

Conclusion

Current treatment strategies for pediatric ALL are associated with acute and long-term neurotoxicity. The incidence of acute and subacute neurotoxicity during pediatric ALL therapy potentially jeopardizes treatment efficacy, while long-term neurocognitive impairment profoundly affects quality of life in survivors of ALL. Emerging evidence indicates that Latino patients may be particularly susceptible to these adverse side effects of therapy. In fact, we recently reported that Latino patients with ALL experience acute and subacute neurotoxic events at a rate far exceeding their non-Latino counterparts [8]. Some evidence suggests that acute toxicity predisposes affected individuals to long-term neurocognitive and behavior complications as survivors [30]; therefore, Latino survivors may be particularly vulnerable. Unfortunately, studies of neurotoxicity during pediatric ALL therapy have largely neglected Latino populations. Future well-designed studies are needed to characterize neurotoxicity outcomes in Latino patients, while considering factors associated with disparities in cognitive performance in the general population, including SES and acculturation. Ultimately, a better understanding of the various factors likely responsible for disparities in neurotoxicity, including inherited genetic variation, clinical characteristics, and sociocultural differences, is needed to improve outcomes for Latino populations.

References

Linabery AM, Ross JA. Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the U.S. (1992–2004). Cancer. 2008;112(2):416–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23169.

Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1541–52. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1400972.

Kadan-Lottick NS, Ness KK, Bhatia S, Gurney JG. Survival variability by race and ethnicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2008–14. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.15.2008.

Bhojwani D, Sabin ND, Pei D, Yang JJ, Khan RB, Panetta JC, et al. Methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity and leukoencephalopathy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(9):949–59. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.53.0808.

Mahoney DH Jr, Shuster JJ, Nitschke R, Lauer SJ, Steuber CP, Winick N, et al. Acute neurotoxicity in children with B-precursor acute lymphoid leukemia: an association with intermediate-dose intravenous methotrexate and intrathecal triple therapy--a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1712–22. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1998.16.5.1712.

Afshar M, Birnbaum D, Golden C. Review of dextromethorphan administration in 18 patients with subacute methotrexate central nervous system toxicity. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;50(6):625–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.01.048.

Giordano L, Akinyede O, Bhatt N, Dighe D, Iqbal A. Methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity in Hispanic adolescents with high-risk acute leukemia-A case series. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(3):494–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2016.0094.

Taylor OA, Brown AL, Brackett J, Dreyer ZE, Moore IK, Mitby P, et al. Disparities in neurotoxicity risk and outcomes among pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(20):5012–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-0939.

Magge RS, DeAngelis LM. The double-edged sword: neurotoxicity of chemotherapy. Blood Rev. 2015;29(2):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2014.09.012.

Dufourg MN, Landman-Parker J, Auclerc MF, Schmitt C, Perel Y, Michel G, et al. Age and high-dose methotrexate are associated to clinical acute encephalopathy in FRALLE 93 trial for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Leukemia. 2007;21(2):238–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404495.

Yang JJ, Cheng C, Devidas M, Cao X, Fan Y, Campana D, et al. Ancestry and pharmacogenomics of relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):237–41. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.763.

Karol SE, Larsen E, Cheng C, Cao X, Yang W, Ramsey LB, et al. Genetics of ancestry-specific risk for relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1325–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2017.24.

Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467(7311):52–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09298.

Mao X, Bigham AW, Mei R, Gutierrez G, Weiss KM, Brutsaert TD, et al. A genomewide admixture mapping panel for Hispanic/Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(6):1171–8. https://doi.org/10.1086/518564.

Duffner PK, Armstrong FD, Chen L, Helton KJ, Brecher ML, Bell B, et al. Neurocognitive and neuroradiologic central nervous system late effects in children treated on Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) P9605 (standard risk) and P9201 (lesser risk) acute lymphoblastic leukemia protocols (ACCL0131): a methotrexate consequence? A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36(1):8–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/mph.0000000000000000.

Cole PD, Kamen BA. Delayed neurotoxicity associated with therapy for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12(3):174–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20113.

Conklin HM, Krull KR, Reddick WE, Pei D, Cheng C, Pui CH. Cognitive outcomes following contemporary treatment without cranial irradiation for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(18):1386–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djs344.

Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, Bowman WP, Sandlund JT, Kaste SC, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2730–41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0900386.

Peterson CC, Johnson CE, Ramirez LY, Huestis S, Pai AL, Demaree HA, et al. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological sequelae of chemotherapy-only treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(1):99–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21544.

von der Weid N, Mosimann I, Hirt A, Wacker P, Nenadov Beck M, Imbach P, et al. Intellectual outcome in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated with chemotherapy alone: age- and sex-related differences. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(3):359–65.

Campbell LK, Scaduto M, Sharp W, Dufton L, Van Slyke D, Whitlock JA, et al. A meta-analysis of the neurocognitive sequelae of treatment for childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(1):65–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20860.

Krull KR, Okcu MF, Potter B, Jain N, Dreyer Z, Kamdar K, et al. Screening for neurocognitive impairment in pediatric cancer long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4138–43. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.16.8864.

Cheung YT, Krull KR. Neurocognitive outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on contemporary treatment protocols: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;53:108–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.03.016.

Jacola LM, Krull KR, Pui CH, Pei D, Cheng C, Reddick WE, et al. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive outcomes in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on a contemporary chemotherapy protocol. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(11):1239–47. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.64.3205.

Reddick WE, Taghipour DJ, Glass JO, Ashford J, Xiong X, Wu S, et al. Prognostic factors that increase the risk for reduced white matter volumes and deficits in attention and learning for survivors of childhood cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(6):1074–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24947.

Carey ME, Haut MW, Reminger SL, Hutter JJ, Theilmann R, Kaemingk KL. Reduced frontal white matter volume in long-term childhood leukemia survivors: a voxel-based morphometry study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(4):792–7. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0904.

Kesler SR, Tanaka H, Koovakkattu D. Cognitive reserve and brain volumes in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Brain Imaging Behav. 2010;4(3–4):256–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-010-9104-1.

Aukema EJ, Caan MW, Oudhuis N, Majoie CB, Vos FM, Reneman L, et al. White matter fractional anisotropy correlates with speed of processing and motor speed in young childhood cancer survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(3):837–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.060.

Khong PL, Leung LH, Fung AS, Fong DY, Qiu D, Kwong DL, et al. White matter anisotropy in post-treatment childhood cancer survivors: preliminary evidence of association with neurocognitive function. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):884–90. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.02.4505.

Nassar SL, Conklin HM, Zhou Y, Ashford JM, Reddick WE, Glass JO, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes among children who experienced seizures during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26436.

Banerjee P, Rossi MG, Anghelescu DL, Liu W, Breazeale AM, Reddick WE, et al. Association between anesthesia exposure and neurocognitive and neuroimaging outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1094.

Jacola LM, Edelstein K, Liu W, Pui CH, Hayashi R, Kadan-Lottick NS, et al. Cognitive, behaviour, and academic functioning in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(10):965–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30283-8.

Kanellopoulos A, Andersson S, Zeller B, Tamnes CK, Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, et al. Neurocognitive outcome in very long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia after treatment with chemotherapy only. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(1):133–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25690.

Holmqvist AS, Wiebe T, Hjorth L, Lindgren A, Øra I, Moëll C. Young age at diagnosis is a risk factor for negative late socio-economic effects after acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55(4):698–707. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22670.

Pierson C, Waite E, Pyykkonen B. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of chemotherapy in the treatment of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(11):1998–2003. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26117.

Patel SK, Lo TT, Dennis JM, Bhatia S. Neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes in Latino childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(10):1696–702. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24608.

Bava L, Johns A, Kayser K, Freyer DR. Cognitive outcomes among Latino survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma: a cross-sectional cohort study using culturally competent, performance-based assessment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26844.

Hackman DA, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(2):65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.003.

Lawson GM, Farah MJ. Executive function as a mediator between SES and academic achievement throughout childhood. Int J Behav Dev. 2017;41(1):94–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415603489.

Dores GM, Devesa SS, Curtis RE, Linet MS, Morton LM. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001–2007. Blood. 2012;119(1):34–43. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-04-347872.

Bhatia S, Sather HN, Heerema NA, Trigg ME, Gaynon PS, Robison LL. Racial and ethnic differences in survival of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100(6):1957–64. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-02-0395.

Lim JY, Bhatia S, Robison LL, Yang JJ. Genomics of racial and ethnic disparities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2014;120(7):955–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28531.

Yang JJ, Landier W, Yang W, Liu C, Hageman L, Cheng C, et al. Inherited NUDT15 variant is a genetic determinant of mercaptopurine intolerance in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(11):1235–42. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.59.4671.

Moore IM, Lupo PJ, Insel K, Harris LL, Pasvogel A, Koerner KM, et al. Neurocognitive predictors of academic outcomes among childhood leukemia survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(4):255–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000293.

Adler NE, Stewart J. Preface to the biology of disadvantage: socioeconomic status and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05385.x.

Llorente AM. Principles of neuropsychological assessment with Hispanics: theoretical foundations and clinical practice. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 2007.

Advisers CoE. Changing America: indicators of social and economic well-being by race and Hispanic origin. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1998.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x.

Hardy KK, Embry L, Kairalla JA, Helian S, Devidas M, Armstrong D, et al. Neurocognitive functioning of children treated for high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia randomly assigned to different methotrexate and corticosteroid treatment strategies: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2700–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.71.7587.

Baker CE. Mexican mothers’ English proficiency and children’s school readiness: mediation through home literacy involvement. Early Educ Dev. 2014;25(3):338–55.

Quiroz BG, Snow CE, Jing Z. Vocabulary skills of Spanish—English bilinguals: impact of mother–child language interactions and home language and literacy support. Int J Biling. 2010;14:379–99.

Harris JG, Llorente AM. Cultural considerations in the use of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—fourth edition (WISC-IV). In: WISC-IV clinical use and interpretation. San Diego: Elsevier; 2005. p. 381–413.

Kishi S, Cheng C, French D, Pei D, Das S, Cook EH, et al. Ancestry and pharmacogenetics of antileukemic drug toxicity. Blood. 2007;109(10):4151–7. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-10-054528.

Vagace JM, Caceres-Marzal C, Jimenez M, Casado MS, de Murillo SG, Gervasini G. Methotrexate-induced subacute neurotoxicity in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia carrying genetic polymorphisms related to folate homeostasis. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(1):98–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21897.

Xiao H, Xu J, Zhou X, Stankovich J, Pan F, Zhang Z, et al. Associations between the genetic polymorphisms of MTHFR and outcomes of methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5):728–33.

Yousef AM, Farhad R, Alshamaseen D, Alsheikh A, Zawiah M, Kadi T. Folate pathway genetic polymorphisms modulate methotrexate-induced toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83(4):755–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-019-03776-8.

Zhao M, Liang L, Ji L, Chen D, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, et al. MTHFR gene polymorphisms and methotrexate toxicity in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(9):1005–17. https://doi.org/10.2217/pgs-2016-0004.

Muller J, Kralovanszky J, Adleff V, Pap E, Nemeth K, Komlosi V, et al. Toxic encephalopathy and delayed MTX clearance after high-dose methotrexate therapy in a child homozygous for the MTHFR C677T polymorphism. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(5b):3051–4.

Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10(1):111–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng0595-111.

Kishi S, Griener J, Cheng C, Das S, Cook EH, Pei D, et al. Homocysteine, pharmacogenetics, and neurotoxicity in children with leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3084–91. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2003.07.056.

Quinn CT, Griener JC, Bottiglieri T, Hyland K, Farrow A, Kamen BA. Elevation of homocysteine and excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters in the CSF of children who receive methotrexate for the treatment of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(8):2800–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.8.2800.

Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brown, A.L., Raghubar, K.P., Scheurer, M.E., Lupo, P.J. (2023). Acute and Long-term Neurological Complications of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) Therapy in Latino Children. In: Ramirez, A.G., Trapido, E.J. (eds) Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14436-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14436-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14435-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14436-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)