Abstract

This chapter deals with gender economics, gender and management, and gender and innovation. After introducing the general concept of feminist economics and its critique of mainstream economics, this chapter explains the meaning of gender indicators, gender parity, gender equality, and gender mainstreaming. It further investigates the factors causing inequalities in the labour market. Gender is afterwards addressed from a managerial perspective, embracing a multidimensional notion of performance, and considering both the management of private and public organisations. Finally, the topic gender and innovation is deepened by explaining the importance of intellectual property rights, as well as the poor visibility of women inventors in society.

Authors are listed in alphabetical order. Although all the authors agreed on the contents of the chapter, Sect. 18.5 (and the related sections) is to be attributed to Francesca Costanza, who also coordinated the writing, Sect. 18.2 is attributable to Sofia Strid, Sects. 18.3 and 18.4 to Manuela Ortega Gil, Sect. 18.6 to Lydia Bares Lopez. Finally, Sect. 18.1 and 18.7 result from the joint efforts of all the authors.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Gender equality is a complex topic, with important ramifications in economy and society. Within this chapter, an overview of key gender concepts and issues within the economic and management disciplines is discussed. In reviewing these key concepts and issues, this chapter conveys the importance of both teaching and studying gender competent economics. This chapter starts with a general section on feminist economics, conceptualised as an economics focused approach on what is needed to produce a gender equal society. It introduces different feminist critiques of mainstream economics and the idea(l)s of homo economicus, exploring the role of gender and intersecting inequalities in the history of economic thinking. In turn, this illustrates how macroeconomic policy both produces and reproduces differential opportunities for women, men and further genders.

The following section devoted to introducing gender indicators from an economic perspective. This distinguishes gender parity, gender equality, and gender mainstreaming indicators, pointing out key databases to extract and analyse them, and the importance of doing so. The chapter then considers gender in the labour market, investigating the factors responsible for causing inequalities in opportunity distribution and wages. Therefore, a focus on gender and management faces gender equality and its relevance in modern management, embracing a multidimensional notion of performance and considering both private and public management aspects. Finally, this chapter addresses gender and innovation by explaining the importance of intellectual property rights (patents), and the poor visibility of women inventors in society.

Learning Goals

Students will learn about and gain a basic understanding of

The key concepts in gender economics and feminist critique of mainstream economics

The meaning and function of gender indicators from the economic and innovation perspectives

Key concepts and tools in gender and management

2 Feminist Economics

Feminist economics has predominantly developed over the last 30 years, in particular with the emergence of the International Association for Feminist Economics and the journal Feminist Economics (Taylor and Francis). Its roots are significantly older, building on the USA and British political economy movements and social (welfare) reforms as their philosophical and political underpinnings. These include, in particular, John Stuart Mill, Harriet Taylor Mill, and Millicent Fawcett, writing about, and campaigning for, women’s and workers’ rights.Footnote 1

Feminist economics is, in its most basic definition, the critical study of (mainstream) economics with a focus on gender inclusive economics and economic policy analysis. It calls for an inclusive critical inquiry, not only in terms of topics, but also in terms of who studies the topics, and what truths are taken for granted. It explores the influence of gender on economics, and conversely, the influence of economics on gender. Feminist economics adds a gendered eye to the field of (mainstream) economics; scrutinising and developing it, often to include what mainstream economics historically has considered “feminine” topics or “women’s issues”. It focuses on how different economic structures enable and reproduce gender regimes by privileging men’s interests over the interests of women.Footnote 2 A crucial outcome of gender economics, and putting it into practice, is the potential to address and contribute towards the solution to some of the most pressing contemporary social, economic, and environmental concerns. Namely, the environmental and economic inequality crises, where (a) feminist practices of degrowth with care at the centre constitute a foundation for economic, ecological and social sustainability, and (b) broadening economic practices with the inclusion of gendered and intersectional perspectives. This enables a complete and accurate understanding of economic phenomena, patterns and mechanisms to reduce economic inequality. Two major concerns are the gendered division of labour in the market economy and the gender distribution of unpaid work within the household, in the interrelation of the two.Footnote 3

The word economics comes from the Greek ‘oikonomia’, meaning ‘household management’. The contemporary meaning of the term has however expanded, or narrowed, from a feminist point of view, to exclude the productions outside of the market and to include only the public production, distribution and consumption of goods and services: to study the market at the expense of the household. A key feature of feminist economics is therefore to bring the household perspective, particularly including the provision of care and unpaid work/domestic labour, back into gender analysis of economics, and to show the interrelation between the “private” and the “public”. It simultaneously highlights the problems posed by a “unitary” conceptualisation of the household.Footnote 4 In making this a focus, feminist economics seeks to challenge notions of “work” and “production” based solely on public production, as contrasted to ‘private’ production and manufacturing, rethinking the status of the different sorts of activities that occur within our economy.

Looking at the division of unpaid work and time use patterns, these are strikingly gendered: women, on average, carry out substantially more unpaid work than men, including food management, cleaning, ironing, laundry and care work. National time use surveys show that in Ireland, Italy and Portugal, women carry out more than 70% of unpaid work. In the more (often regarded) gender equal countries of the North, women are still doing almost two-thirds of such unpaid work.Footnote 5

Gender is consequently strongly related to unpaid work, both historically and in contemporary discourse and data: the amount of time people invest in unpaid versus paid work; the distribution of unpaid work time between different tasks, and the patterns of unpaid care work are largely determined by a person’s gender. Despite a shift from women as workers in the private to women as workers in the public, occasionally referred to a shift from private patriarchy to public patriarchy,Footnote 6 women continue to bear the responsibility for, and spend more time, than men on unpaid housework and unpaid care work, regardless of their employment status. Further, women’s spare time and volunteer activities are more likely to be related to family than are men’s.Footnote 7 Women often work double shifts; a first shift paid outside of their home, and a second shift of unpaid domestic work. This is often referred to as women’s double burden.Footnote 8 While this work remains unpaid and undervalued, it is crucial to the economy; keeping current workers and consumers alive and healthy, raising new generations of workers and consumers, and producing a value in itself. Therefore, not only is the gendered division of unpaid work a problem in itself, it also has a bearing on the labour market and women’ participation therein; the two ‘markets’, the domestic/private and the public, are interrelated. In exploring how mainstream economics, including economic statistics and economic policy, would have to change in order to attribute a value to the contributions of women, some of the pioneering feminist criticism deconstructed the very basis and rational for ‘modern’ economics.Footnote 9

2.1 Gender and the ‘Economic Man’

Fundamentally, it has been argued that since modern economics is based on the notion of the “economic man”, it is necessarily ideologically and politically loaded towards normalising the work and life experiences of men. Economics subsequently ignores the experiences of women, as well as those of men who do not fit the norm.Footnote 10 Introduced in the 1800s by John Stuart Mill, the concept of the ‘economic man’, or ‘homo economicus’ was perceived as an economic actor “who inevitably does that by which he (sic) may obtain the greatest amount of necessaries, conveniences, and luxuries, with the smallest quantity of labour and physical self-denial with which they can be obtained”.Footnote 11 Hence, the argument follows that the political economy removes all human desires, emotions, and ‘irrationalities’, except those that assist in the pursuit of wealth.

There has been extensive critique of the idea(l)s of homo economicus, including from within mainstream economics itself; human behaviour is irrational, and economic actors are neither always fully informed when making economic decisions, nor do they always act in their own self-interest. Despite such critique, the assumption, and ideal, of a rational economic man remains in both microeconomic and macroeconomic models in some of the most influential contemporary work (e.g., Piketty)Footnote 12 and everyday thinking.Footnote 13

Whilst it is self-evident what this typical ‘economic man’ does: he works; earns an income; engages in market transactions and spends money on the consumption of goods. Contemporaneously it is equally clear what he does not: he does not do unpaid housework chores, and he does not have caring responsibilities. Hence, economic models based on the ‘economic man’ cannot incorporate, recognise or demonstrate gendered or intersectional inequalities. Without such recognition and visibility of multiple and complex gendered inequalities, policies to reduce them are bound to fail.Footnote 14

The notion and idea of the economic man is not necessarily a figuration in the interests of men either; in building on homo economicus, the traditional economic models provide both an incomplete and inaccurate model of what affects men’s lives too. Men’s existence is not disconnected from, but rather depends on, the performance of unpaid work and the production and use of care. Further, men are not only the recipients of such work and care, indeed, some men are directly involved in these activities too. Finally, the notion of homo economicus fails to recognise the existence of further genders. The conclusions, from the perspective of feminist economics and from a gender perspective more broadly, are that a wider concept of what constitutes both the economy and gender are required. The very existence of the current system, under mainstream economics and economic theory, depends on activities outside of its empirical and theoretical scopeFootnote 15 and by economic actors beyond the gender binary.

Feminist economics is therefore a necessarily comprehensive academic field, encompassing a wide range of areas aiming to add nuance and complexity to an already established field. Key areas of study within feminist economics go beyond the care economy and unpaid work (e.g. caring labour, time-use surveys, household expenditures, same-sex and lone mother families, sexuality and reproduction, and family and social policy). For example, the journal Feminist Economics, the international scholarly journal of the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE), published by Taylor and Frances, includes articles on a wide range of topics, including:

-

environmental economics (e.g., the economic effects of national or local environmental policy, the costs and benefits of alternative environmental policies, and global warming);Footnote 16

-

feminist theory and economics (including e.g., methods and argument, the history of thought, and feminist theories);

-

labour markets (including e.g., stratification, employment and labour force participation, wage outcomes, wage gaps, wage discrimination, firm performance, labour market policies, informal labour, and time stress; land, agriculture and rural development);

-

LGBTQIA+ economic issues; income poverty and capability deprivations (including e.g., income, poverty and capability deprivations, migration, microfinance, rights/international human rights and national, capabilities-based evaluations of outcomes, including index measures);

-

assets, education, conflict/warfare, environmental degradation and climate crisis;

-

and macroeconomics contexts (including e.g., crises, trade structure, financialisaton, gender budgeting, macroeconomics policies and outcomes, gender mainstreaming, and international institutions).

Just as there are multiple linkages and interrelations between unpaid work and the conventional macroeconomy per se, these fields of study are also interlinked, suggesting to feminist economists that it is necessary to expand the boundary of conventional macroeconomics to incorporate unpaid work.

Returning to the key feature of unpaid work and the macro level, there is much empirical work and efforts to integrate unpaid work into macro policies, in particular, efforts to interrogate and understand the impacts and effects of macroeconomic policy on both paid and unpaid work, and on the relation between them. Unpaid work raises the overall well-being of the economy; it entails the productive use of human labour, and through the caring and rearing of children, unpaid work contributes to the formation of human capital. While unpaid work is excluded from, and falls outside of, the national income accounts and GDP measurements, it falls within the general production boundary. Further, various mainstream experts view unpaid work as either “care” or “work”. The near global unequal distribution of work between men and women implies a violation of the basic human rights of women, with unpaid care work having an enormous impact on women’s poverty and capacity to exercise their rights, and the exclusion of women’s experiences and some men’s experiences of work reflect the dominance of patriarchal values, bringing male bias into macroeconomics.

2.2 Gendering for Objectivity

The manifesto of feminist economics, Ferber and Nelson’s Beyond Economic Man: Feminist Theory and Economics,Footnote 17 argued the very discipline of economics needed to free itself from both the dominance of men and from the bias of masculinity in economics. Further, and perhaps somewhat counter-intuitive to much feminist work, Ferber and Nelson raised questions regarding the discipline, not because economics is too objective, but because it is not objective enough. This epistemological critique firstly raised an empirical knowledge concern and discussed the extent to which gender influenced both the range of subjects studied by economists, and secondly, a methodological concern by questioning the very ways in which scholars have conducted their studies.

To summarise the main lines of critique of conventional/mainstream economics: (1) the majority men, or the norm group of men and their interests and concerns underlie economists’ concentration on markets, as opposed to household activities; (2) the emphasis on individual choice necessarily renders social and economic inequalities invisible, and their constraints/limitations on choice unrecognised; and (3) the focus on cis men’s interests has biased the definition and boundaries of the discipline; its central assumptions, its choice and acceptance of methods, and its results. To move forward, it is important to note that the objective of feminist economics is not to reject mainstream economic theory or economic practices, but rather to broaden them with the inclusion of gendered and intersectional perspectives, thereby enabling a fuller, and more accurate, understanding of economic phenomena, patterns, and mechanisms.

3 Indicators of Gender from the Economic Perspective

Indicators are essential for the study and analysis of social phenomena. Currently, there is no official definition of an indicator by any national or international body, although based on the contributions of different organisations and authors such as BauerFootnote 18 or Land,Footnote 19 it can be defined as an instrument that provides a measure of a concept, phenomenon, problem, or social fact. Indicators can be divided into qualitative or quantitative, simple, or synthetic (if it includes several components).

The combined set of indicators is called an index. Indices help to measure complex phenomena that have different dimensions and need a set of indicators to reflect a more complete reality of the analysed phenomenon. Both indicators and indices are used for the research and visualisation of social problems and phenomena, to follow changes over time.

A gender indicator, therefore, serves to measure the state of women compared to men in different dimensions of people’s lives, related to gender equality in a region.

Definition

Gender indicators could be grouped into three dimensions:

Gender equality: the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE)Footnote 20 defines it as “Equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys”. It is an indicator of sustainable development.

Gender parity: it can be focused as “the equal contribution of women and men to every dimension of life, whether private or public”.Footnote 21 It is also related to the terms gender balance, parity, parity democracy.

Gender mainstreaming: it involves the integration of a gender perspective into all public policy making process, regulatory measures, and spending programmes, with a view to promoting equality between women and men, and combatting discrimination. Gender mainstreaming contains two dimensions: equal representation of men and women, and gender perspective in the content of policies.Footnote 22

3.1 Main Indicators of Gender Equality

The complexity of the gender equality concept has led to the creation of composite indicators of different dimensions. Among them, the following stand out:

Gender Equality Index (GEI): is used to measure the progress of gender equality in the EU. It is a tool that supports policy makers in designing more effective gender equality measures, by allowing meaningful comparisons between different gender equality domains.Footnote 23 It is based on six domains (work, money, knowledge, time, power, health), two additional domains (violence and intersecting inequalities) and 14 subdomains and 31 indicators.Footnote 24 For example, GEI of EU in 2020 edition is 67.9 out of 100 points (work = 72.2, money = 80.6, knowledge = 63.6, time = 65.7, power = 53.5, health = 88.0).

Gender Parity Index (GPI): introduced by UNESCO to measure the access to education for men and women (ratio of female to male values at a given stage of education). A GPI close to one indicates parity between the genders, below 0.97 indicates a disparity in favour of males, and above 1.03 indicates a disparity in favour of females.Footnote 25 For example, the gender parity index (GPI) of the world in 2019 was 1.131 in the school enrolment, tertiary (gross), 0.986 in school enrolment, primary and secondary (gross) and 0.981 in school enrolment, primary (gross).

Gender Inequality Index (GII): is released by the UNDP and “measures the human development costs of gender inequality”.Footnote 26 Thus, the higher the GII value, the more disparities between females and males and more loss to human development. The country with the lowest value in 2019 was Switzerland with 0.025. The country with the highest value, the highest inequality, of the 189 countries analysed was Yemen with 0.795 It includes three aspects: reproductive health, empowerment, and economic status. In turn, this is demonstrated through the following five indicators:

Reproductive health: maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birth rate. In 2017, the country with the highest maternal mortality ratio was South Sudan with 1150 per 100,000 live births. Between 2015–2020, Niger was the country with the highest adolescent birth rate, at 186.5 births per 1000 women ages 15–19.

Empowerment: female and male population with at least secondary education and Female and male shares of parliamentary seats. In 2019, the country with the highest percentage share of seats in parliament held by women was Rwanda with 55.7%.

Economic status: female and male labour force participation rates. In 2019, the country with the highest force participation rate was Singapore with 1.041.

Global Gender Gap Index:Footnote 27 was presented in 2006 by World Economic Forum (WEF). In the Global Gender Gap Report (2021), the highest ranking countries in terms of equality are Iceland (89.2) followed by Finland (86.1) and Norway (84.9). This index is founded on three basics: “First, on measuring gaps rather than levels. Second, it captures gaps in outcomes variables rather than gaps in means or input variables. Third, it ranks countries according to gender equality rather than women’s empowerment”.Footnote 28 It measures one important aspect of gender equality; the relative gaps between women and men across a large set of countries, and covering four key areas (Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment).Footnote 29 These four dimensions are composed of the following indicators:

-

1.

Five indicators of Economic Participation and Opportunity: labour force participation rate; wage equality for similar work; estimated earned income; legislators, senior officials, and managers; professional and technical workers,

-

2.

Four indicators of Educational Attainment: literacy rate; enrolment in primary education; enrolment in secondary education; enrolment in tertiary education.

-

3.

Two indicators of Health and survival: sex ratio at birth and healthy life expectancy (years).

-

4.

Three indicators of Political Empowerment: women in parliament, women in ministerial positions and years with female/male head of state (last 50).

The main sources of data collecting gender indicators at international, European, and national level are: World Bank (WB),Footnote 30 United Nations (UN),Footnote 31 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),Footnote 32 European Statistics (Eurostat),Footnote 33 European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE),Footnote 34 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP),Footnote 35 UNESCO.Footnote 36

3.2 Sustainable Development Goals and Gender Equality

The General Assembly of United Nations approved the Agenda for Sustainable Development in September 2015. This agenda includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of universal application that govern the efforts of countries to achieve a sustainable world by 2030 (1. No poverty; 2. Zero Hunger; 3. Good health and Well-being; 4. Quality Education; 5. Gender Equality; 6. Clear Water and Sanitation; 7. Affordable and Clear Energy; 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth; 9. Industry, Innovation and infrastructure; 10. Reduce Inequalities; 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities; 12. Responsible Consumption and Production; 13. Climate Action; 14. Life Below Water; 15. Life on Land; 16. Peace, Justice and Strong Institution; 17. Partnerships for the Goals). These goals are designed to achieve a sustainable future for all and to combat the challenges facing the Earth.

The European Statistics collect indicators to measure the fulfilment of Goal 5 from the aforementioned Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), namely, to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”. Such indicators are:

-

Physical and sexual violence to women.

-

Gender pay gap in unadjusted form.

-

Gender employment gap.

-

Inactive population due to caring responsibilities.

-

Seats held by women in national parliaments and governments.

-

Positions held by women in senior management positions.

-

Early leavers from education and training.

-

Tertiary educational attainment.

-

Employment rates of recent graduates.

4 Gender in the Labour Market

The labour market is characterised by demands for goods and services, the productivity of workers and the cost of labour, and a supply represented by the labour force comprising all persons fulfilling the requirements for inclusion among the employed (civilian employment plus the armed forces) or the unemployed.Footnote 37 The labour market is diverse and segmented, mainly by age, sex, education and training, and citizenship. Many studies show that gender inequality exists. According to Eurostat, the gender employment gap in the European Union is considerable (EU-28 average 11.4%), highlighting significant differences between Member States; ranging from 1.6% of the population in Lithuania, to 20.7% in Malta (Fig. 18.1).

The main factors causing inequal feminist socioeconomics in work and employment are:

-

persistent gender division of domestic and care work;

-

interplay of workplace and household power relations shapes good/bad job segmentation;

-

gendered wage practices target first and second earners;

-

economic cycles (booms and busts) have gendered employment effects;

-

occupational sex segregation, including feminised part-time work, influences the accompanying job design, career tracks and wage value; jobs associated with women (‘women’s work’) are undervalued;

-

sex discrimination by employers, co-workers and customers is shaped by powerful stereotypes about motherhood, and

-

different standards and gendered models of family support provision.Footnote 38

There remains a significant gender gap caused, among many factors, by occupational segregation, differences in academic specialisation, difficulty in balancing work and household responsibilities, and wage discrimination.Footnote 39 In addition, the labour market is immersed in a process of transformation caused by the introduction of the digital world into everyday life. This was accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic; during the year 2020, teleworking and online work patterns increased considerably.

The study by Frey and OsborneFootnote 40 indicates that the process of digitalisation of the labour market is expected to take place in two waves. It is thought the first wave is currently underway; workers in transportation and logistics occupations, office and administrative support workers, as well as labour in production occupation, will be substituted by computer capital. This stage is to be followed by a “technological plateau” before entering the second wave. This second wave depends on the capacity of the engineering bottlenecks related to creative and social intelligence, encompassing the generalist occupations specialised in the human aspect, and specialist occupations involving the development of novel ideas and artifacts.Footnote 41 Against this background, educational attainment remains a key to improve employability and labour market outcomes.Footnote 42

In turn, the digitalisation process can improve gender equality. The characteristics of the tasks currently performed by women, the robotisation of domestic tasks, teleworking, and social skills will open new opportunities for female employment.Footnote 43 The jobs held by women require high nonroutine manual or social skills, and this creates bottlenecks to digitalisation and automation. This opportunity will depend on the entry of women into jobs benefitting most from digitalisation (management, science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and entrepreneurship) in roles where they are currently in the minority, shown by recent data on the gender gap.Footnote 44

In 2015, although globally women were more educated than men on the average, their chances of rising to leadership positions were exceptionally low and their labour force and wages were lower than those of men.Footnote 45 However, women had increased their participation in professional and technical occupations and controlled 64% of household spending.

In 2019, the European Union showed significant differences in employment (10.4 percentage points), labour force participation rateFootnote 46 (10.8 percentage points) and unemployment rate (−0.4 percentage points) between men and women.Footnote 47 According to literature, age, education, or household financial situation, as well as economic, social and demographic characteristics, influence labour supply behaviour. In poor households, the economic pressure to contribute to household income is more pronounced for both women and men.Footnote 48

There are different approaches to women labour force participation and family structure and household. A study of the Japanese society by SasakiFootnote 49 shows that married women who share the burden of household work with their parents, or in-laws, are more likely to participate in the labour force. Another study illustrated that the wife’s labour supply is inversely related to the quality of the couple’s relationship.Footnote 50

The relationship between women’s education and work outside from home has also been investigated, concluding that women’s bargaining power increases when women are more educated relative to their spouses. Correspondingly, as women’s bargaining power increases, they participate more in the labour market.Footnote 51

5 Gender and Management

Gender equality is a relevant topic in modern management, since the real-life application of gendered policies at any societal level requires a joint effort of many actors (belonging both to private and public sectors), and the development of new awareness, tools, and skills.

For public and private organisations, incorporating the gender perspective in managerial processes means to acknowledge the contribution of gender diversity in affecting leadership styles at any hierarchy level,Footnote 52 and in influencing decision-making processes, information systems and accountability towards civil society.Footnote 53 However, in treating gender and management issues, it is important to consider their intersectionality with other life categories such as class, age, education, sexual orientation.Footnote 54

Table 18.1 summarises the main features of the Gender and Management analysis conducted in this chapter. Each category of organisation (private and public) can be read in light of gender-related criteria.

Noticeably, private and public actors share a common gender-related scope, the realisation of gender equality. In pursuing this scope, each hold specific roles and responsibilities. The economic role played by private organisations makes them potential catalysts of sustainable development.Footnote 55 In contrast, public organisations, through incentives and regulations, oversee sustainable (including gender-related) policy making and implementation at the national and local level. Both spheres are addressed by referring to the Corporate Social Responsibility (or CSR) framework, considered valuable for its breadth and being comprehensive. In addition, the public sphere also considered Public Management and Administration theories and applications.

The fact that this chapter addresses gender and management by considering private and public institutions separately, is not only to facilitate discussion and chapter readability, but also to remark sectoral specificities. However, public and private worlds are not to be intended as “institutional islands”; they continuously communicate, reinforce each other and present overlapping areas. Moreover, the public value management approachFootnote 56 is coherent with the sustainability framework and the descending accountability efforts towards several categories of stakeholders.Footnote 57

Significantly, since the end of the twentieth century, the areas of “contamination” between public and private sectors management have been growing. Indeed, the traditional notion of public institutions, bureaucratic in nature and founded on legal power, has been criticised for its resistance to change.Footnote 58 This notion has been surpassed by: (a) the New Public Management paradigm (or NPM), which postulates the necessity to apply to the public sector tools and techniques from the private one;Footnote 59 and (b) the New Public Governance paradigm (or NPG) which emphasised the contribution of public-private cooperation to deliver value to citizens.Footnote 60

In both public and private organisations, the translation of gender mainstreaming in effective actions implies the adoption of a multidimensional notion of performance. As far as private actors are concerned, CSR business models represent the translation of the sustainability paradigm at a micro-level and the acceptance of an articulated finalism that, in line with the triple bottom line approach,Footnote 61 strives for satisfying balanced results along the economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

In the Public Management and Administration sphere, in conjunction with the affirmation of New Public Governance and Public Value Management paradigmsFootnote 62 the performance notion runs through the entire public value chain and encloses the consideration of inputs, outputs, outcomes. In turn, such measures could be read according to a sustainability lens to highlight social policies, economic policies, and environmental policies.

In the following two sections, public and private managerial concepts and tools will be deepened. In “Gender and Corporate Social Responsibility”, gender diversity and responsiveness will be analysed as part of a virtuous company’s social strategy, able to contribute to other performance dimensions. In “Gender and Public Management and Administration”, the gender mainstreaming approach within public organisations will consider processes of gendered performance management at both top and street management level, and illustrate the role of gender responsive public balance sheets.

5.1 Gender and Corporate Social Responsibility

In recent history, Corporate Social Responsibility has been gaining momentum between scholars and policy makers. It was even included in institutional agendas, particularly after the publication of the CSR Green BookFootnote 63 and the European Commission Directive on CSR.Footnote 64 Such initiatives attempted “to promote a consensus for CSR implementation through debate groups and the participation of diverse social actors”.Footnote 65

There is no unique definition of Corporate Social Responsibility, or CSR (see the contribution of Garrica and Melè for a review).Footnote 66 However, for the scopes of this chapter, CSR can be understood as:

Definition

A company’s commitment to be accountable for the impacts of its activity “minimizing or eliminating any harmful effects and maximizing its long-run beneficial impact on society”.Footnote 67

Furthermore, CSR concept postulates that “companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis”.Footnote 68

Company activity embeddedness in social system is part of its own entrepreneurial formula,Footnote 69 which is valid when “oriented toward simultaneously pursuing success on the competitive, social, and economic levels”.Footnote 70 Thus, beside ethical reasons for Corporate Social Responsibility, it can also be intended as a strategic lever source of competitive advantage,Footnote 71 boosting company reputation within employees,Footnote 72 purchase intentionsFootnote 73 and consumer awareness or attitudes.Footnote 74

Corporate Social Responsibility can be articulated into two areas of study; internal and external CSR. The former concerns inside operations and includes employees related activities. The latter regards other stakeholders such as customers, business partners, community, environment.Footnote 75

Corporate social responsibility is strictly related to sustainable development; a socioeconomic concept implying the satisfaction of actual needs, bearing in mind the necessities required for future generations.Footnote 76 Sustainable development is a broad concept based on three key elements: economic growth; environmental protection, and social inclusion. The sustainable development in practice entails the active role of entrepreneurship,Footnote 77 and, from a managerial perspective, a “triple bottom line” approachFootnote 78 postulating for companies the joint pursuits of economic, environmental, and social performances.Footnote 79 Consequently, profit maximisation as the unique company objectiveFootnote 80 is replaced by the consideration of multiple stakeholder interests in corporate activities.Footnote 81

In this regard, CSR accountability routes to Environment, Social and Governance (ESG); to integrate social and environmental sustainability with governance and long-term corporate vision.Footnote 82 Public awareness regarding ESG principles has converged to the formulation of ESG ratings, “evaluations of a company based on a comparative assessment of their quality, standard or performance on environmental, social or governance issues”.Footnote 83

More specifically, sustainability values are to be included within the vision and “can be addressed during strategic decision-making process and as part of the organisation’s corporate, business and functional level strategies”.Footnote 84

Given the above reasoning, gender equality and responsiveness can be intended as part of a virtuous company’s social strategy, being able to contribute to other performance dimensions. There are three relevant managerial aspects of gender perspective’s inclusion in CSR: gender diversity in companies’ boards; the organisational welfare, and the Corporate Social Responsibility tools (such as standards, codes of ethics and reports).

5.1.1 Gender Diversity in Companies’ Boards

The first indicator of gender diversity within organisations can be envisaged within the board of directors, due to the board’s role in company goal setting, including CSR policies and strategies.Footnote 85 Specifically, boards may integrate socially and environmentally responsible behaviour in the strategic planning process.Footnote 86 Frequently, in homogeneous boards, the decision-making is faster due to convergent opinions and a more fluid communication.Footnote 87 Notwithstanding, in heterogeneous groups, many points of view and skills are taken into consideration to deal with complex problems.Footnote 88

Various scientific contributions highlight the positive impact of boards’ gender diversity on environmental issues; the voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas,Footnote 89 risks of climate changeFootnote 90 and carbon reduction initiative.Footnote 91 According to the study of De Masi and colleagues,Footnote 92 three is a minimum number of female directors required on company boards, to stimulate the disclosure of ESG information, ameliorate ESG score and to encourage the highest contribution of women to governance performance. Indeed, “women’s contribution is visible when the critical mass, identified as three women on boards, is reached, after which the voices of women are heard, and their impact becomes discernible”.Footnote 93

Valls Martínez, Cervantes and RambaudFootnote 94 frame such propensity in five theoretical streams:

-

1.

the social role theory: the fact that women act according to gender roles and social expectations influences their management style. This results in more empathetic and participative leadership,Footnote 95 able to handle CSR and stakeholders’ expectations;

-

2.

the resource dependency theory: according to this theoretical perspective, facing social and environmental issues requires board diversity to intercept many kinds of environmental resources;Footnote 96

-

3.

the legitimacy theory: legitimacy occurs when stakeholders accept a company as a corporate subject characterised by moral citizenship.Footnote 97 In this regard, a diverse board structure can contribute to legitimacy, witnessing sensibility towards women’s potential and equal opportunities;Footnote 98

-

4.

the agency theory: in companies where it is possible to distinguish ownership and control,Footnote 99 there are information asymmetries making managers (the agents) to behave contrary to the principals’ interests (i.e., the shareholders). A diverse board composition can play a role in corporate governance, whereas higher representation of women is likely to mitigate agency costs, due to their tendency to transparency and accountability;Footnote 100

-

(a)

the stakeholder theory: CSR helps a company to comply with stakeholders’ expectations.Footnote 101 Gender diversity contributes to this scope by allowing women moral reasoning of women in meeting stakeholder needs,Footnote 102

-

(b)

the stakeholder agency theory:Footnote 103 this theory combines agency theory and stakeholder theory, assigning to the board a twofold role; as principals for managers, while contemporaneously playing the role of agents according to the stakeholders’ perspective.Footnote 104

-

(a)

5.1.2 The Organisational Welfare

As far as organisational welfare policies are concerned, the use of organisational welfare indicators (for example regarding the balancing of working and private lives) is instrumental to the satisfaction of internal stakeholders (workers), whose needs are to be satisfied to improve their sense of belonging.Footnote 105

Indeed, company performances may be affected by work-family conflicts, arising whenever individuals handle these two life domains.Footnote 106 Organisations can be family-friendly by implementing solutions such as childcare assistance and flexible working hours.Footnote 107

According to Pulejo,Footnote 108 such initiatives contain the ability to make workers feel a sense of company belonging. This is achieved through the reconciliation of family and work responsibilities as they are more effective when implemented in a systemic way, when:

-

(a)

the organisational culture evaluates work on the basis of intrinsic quality instead of time, whereas family commitments do not penalise professional development paths;

-

(b)

the sensitivity to reconciliation issues is widespread at all hierarchical levels,

-

(c)

the family-friendly company policies are clearly communicated and incentivised.

5.1.3 Corporate Social Responsibility Tools

In this subsection the key tools fostering the implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) within companies are described. CSR should go “over and above their legal obligations towards society and the environment”, however “certain regulatory measures create an environment more conducive to enterprises voluntarily meeting their social responsibility”.Footnote 109

The EU Commission acknowledges the key role of international guidelines and principles, such as the ISO 26000 Guidance Standard on Social Responsibility, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.Footnote 110

“According to these principles and guidelines, CSR at least covers human rights, labour and employment practices (such as training, diversity, gender equality and employee health and well-being), environmental issues (such as biodiversity, climate change, resource efficiency, life-cycle assessment and pollution prevention), and combating bribery and corruption”.Footnote 111

However, CSR standards do not automatically affect CSR effectiveness. They are relevant for a symbolic and signalling effect,Footnote 112 thus contributing to external legitimacy without implementing substantial commitment to CSR in organisations.Footnote 113 As remarked by Testa and colleagues,Footnote 114 CSR company internalisation depends on a series of “hard” and “soft” factors, whereas CSR standards are part of the hard determinants, together with other formal structures and routines (technology, accounting and management systems, etc…). Among the soft determinants to CSR, there are the citizenship behaviours of managers, the employees’ commitment and a leadership based on good examples.Footnote 115 Other important tools helping CSR implementation at a company level are codes of ethics and conducts. CSR reports published together with financial information started to be elaborated after multiple corporate scandals in the 1990s.Footnote 116 Company nonfinancial information can be issued through social reports (or sustainability reports). These can consist of stand-alone reports, dealing with sustainability aspects and disclosing the organisational interrelations within the natural and social environment.Footnote 117 However, these reports have been criticised for their lack of a holistic view of performance, since they do not link social and environmental performance with financial information.Footnote 118 For these reasons, they must be replaced by integrated reports; corporate disclosure reports combining information regarding financial and non-financial performance.Footnote 119

5.2 Gender and Public Management and Administration

In this section, the gender mainstreaming approach within public organisations considers processes of gendered performance management at both top and street management level. This illustrates the role of public balance sheets in disclosing the socioeconomic impact of gender related policies’ implementation, and the potential impact of non-gendered policies on gender related issues.

As aforementioned, we assume a multi-dimensional definition of performance, based on the distinction between inputs (resource consumed), outputs (amount of goods and services produced), and outcomes (long-term socioeconomic impacts). Such an approach is coherent with the evolution of Public Management and Administration theory and practice, whereas the traditional bureaucratic control on inputs has been overpassed by managerial and governance-based models. Such models are more focused on public results, namely, outputs and outcomes.Footnote 120 According to Moore,Footnote 121 public managers are responsible for creating public value; a key evaluative criterion within a performance-based perspective. Moore distinguishes three public management tasks: managing upward; downward, and outward, implying specific behavioural features:Footnote 122

Managing upward; it takes place when public top managers interact with their principals, their elected political leadership. In this sphere, public performance could benefit from more gender-representative organisations, as women managers appear to be more participatory, interactional, flexible,Footnote 123 and increase or at least maintain managerial resources and legitimacy.Footnote 124 Managing outward; is based on the managers’ interactions within the networked character of public programs, with organisational success based on the capacity to keep links with the community. Both men and women managers make use of such networks, with males excelling in informal connections and females privileging formal networking.Footnote 125 Managing downward; is the classic, hierarchical public management mechanism, characterised by the managers’ interactions with subordinate line managers. Here, female managers may struggle for authority, due to an image of organisational leadership mostly associated to masculine terms for executive positions,Footnote 126 unbalanced domestic responsibilities,Footnote 127 and the underestimation of emotional labour skills.Footnote 128 As a result, females in middle or top-level management positions are rarer than ones occupying street-level positions.Footnote 129

In this context, public balance sheets, or public budgets, can help in promoting gender equality, by representing governmental statements of priorities in expenditures and revenues. We adopt the definition of “gender responsive budget” provided by Rubin and Bartle,Footnote 130 as a “government budget that explicitly integrates gender into any or all parts of the decision-making process regarding resource allocation and revenue generation”.Footnote 131 The budgeting initiatives enclosing the gender perspective function at the level of national or subnational government.Footnote 132 The use of gender responsive public budgets started to be encouraged since the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women”.Footnote 133 The aims of the Convention were confirmed by the United Nations’ Fourth World Conference on Women, pushing governments to “incorporate a gender perspective into the design, development, adoption and execution of all budgetary processes as appropriate in or to promote equitable, effective and appropriate resource allocation and establish adequate budgetary allocations to support gender equality”.Footnote 134 Later, the “European pact for gender equality”Footnote 135 prescribed to include the gender view into public policies’ monitoring and evaluation at the European level, including the Union’s public budgeting processes. Furthermore, the document encourages peripheral initiatives, promoting gender responsive budgets at a local level and the exchange of best practices.Footnote 136

Public budgets are made of financial aggregates, and do not distinguish gender-specific issues or impacts.Footnote 137 However, a budget is only apparently gender neutral, ignoring this fact denotes “gender blindness” about the unintended impacts of budget policies, able to affect both revenue and expenditure.Footnote 138

Some countries (e.g., France, Germany, Italy, and Spain in the context of the European Union)Footnote 139 have undertaken initiatives to create gender-responsive budgets, both at national and/or sub-national levels. These practices share some common traits; they all require the decision-makers’ awareness on gender inequities, and the relevance of budget policies to mitigate them. Acceptance of these initiatives also requires consideration of the roles of the political environment and social values.Footnote 140

Furthermore, efficiency and equity can find a balance in the adoption of gender-equity objectives for the definition of performance measures.Footnote 141 The gender perspective can be integrated in any step of the budget cycle, from preparation to evaluation, as reported by Rubin and Bartle.Footnote 142 Specifically, the authors suggest that in the first stage of public budgeting processes (budget preparation), gender-specific policies and priorities can be inserted.Footnote 143 In the next stage (budget approval), possible gender-responsive actions are, for example, the creation of gender guidelines in allocating resources and the inclusion of gender outcomes in fiscal notes.Footnote 144

At budget execution, departments could be provided with specific guidelines (for spending, outsourcing, procurement, grant disbursement), whilst gender goals are implemented at a staff level.Footnote 145 The final stage of budget audit and evaluation could incorporate the gender perspective, for example, carrying out auditing activities about expenditures, outputs, outcomes, as well as compliance with gender-related goals and guidelines.Footnote 146

Gender-related budgeting requires measuring the impacts of policy making on gender equality. The measuring/evaluation activity should regard all government functions, including seemingly gender-neutral expenditures. Indeed, direct and indirect policy impacts should be considered; one policy targeting a specific segment of population could have indirect (desired or undesired) effects on other segments, and vice versa.

Figure 18.2 proposes a bidimensional matrix to be intended as a general framework for policy analysis. The potential policy packages can be separated into two main categories: gender related policies, explicitly targeting gender inequality (and eventual intersections); and (apparently) gender neutral policies. Each category can affect gender equality and/or other aspects. Thereafter, it is possible to estimate the impact of gender policies on gender inequalities (quadrant I), on other aspects (quadrant II), the impact of gender-neutral policies on gender inequalities (quadrant III) and on other aspects than gender equality (quadrant IV). Gender-responsive budgets should disclose, at least, what is included in quadrants I and III. Notwithstanding, they do not require new formats of balance sheets, but their adaptations should be read according to “gender lenses” in any existing budget format. For example, line-item budgets (organised by objects of expenditure), could separately indicate the percentage of wages/salaries or contracts to women and/or firms owned by women.Footnote 147 In contrast for performance-based budgets, where expenditures are articulated in performance objects, tasks, outputs, and outcomes, the budget document could contain the performance measures capturing gender goals.Footnote 148

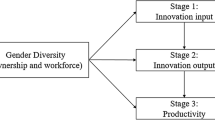

6 Gender and Innovation

The overall aim of this section of this chapter is to analyse the importance of intellectual property rights (patents) and the poor visibility of women inventors in society.

6.1 General Concepts from an Economic Angle

Innovation is a key piece in the economic development of countries. According to the Oslo Manual,Footnote 149 an innovation is “a new or improved product or process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and that has been made available to potential users (product) or brought into use by the unit (process)”. A large number of innovations can be protected through intellectual property (IP) rights.

IP is defined as “creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce”.Footnote 150 Intellectual property is divided into two groups, “industrial property” and “copyright”.

Industrial property includes “inventions in all fields of human endeavour, industrial designs, trademarks, service marks and commercial names and designations” (World Intellectual Property Organization or WIPO). According to WIPO, an invention is “a new solution to a specific technical problem in the field of technology”.Footnote 151

“A patent is a legal title that gives inventors the right, for a limited period (usually 20 years), to prevent others from making, using or selling their invention without their permission in the countries for which the patent has been granted”.Footnote 152

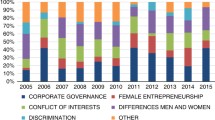

6.2 The Gender Patenting Gap

Gender disparity still exists, despite many excellent intentions and activities. Even though female undergraduate and graduate students outnumber male students in many countries, there are few female full professors. Gender disparities in employment, wages, financing, satisfaction, and patenting still exist.Footnote 153

Many studies have attempted to examine women’s involvement in science, technology, and innovation, primarily utilising statistics from patent filings and scientific publications. By methodically assigning gender to the names of inventors and authors from 14 countries, Frietsch et al.Footnote 154 explored gender-specific patterns in patenting and academic publication. The findings revealed significant disparities in female engagement across countries, with the higher-performing countries showing minimal increase in this area over the study period (1991–2005).

There are several studies that focused their attention in the second country with the most patents in the world; the United States of America.

Murray and GrahamFootnote 155 used bibliometric data and semi-structured interviews to investigate the origination and maintenance of the gender gap in commercial science between 1975 and 2005 in the U.S. Women constituted 56 of a possible 148 life science faculty members (38% of the population), with 34 male (29%) and 22 female (73%) active during 2 years. According to their findings, key determinants of gender stratification in commercial science can be traced back to “when early buyers in the market activated traditional cultural stereotypes of women in science and business and showed an initial gender bias in the opportunities available to women life scientists”. Homophily in mentoring and networks, among other factors, reinforced these traits through generations. While the study’s findings were limited in their generalisability, they did agree that the lack of a supporting network for the patenting procedure was the most important factor in shifting gender prejudice.

Whittington and Smith-DoerrFootnote 156 looked into gender differences in commercial engagement for both industrial and university life scientists. Their findings revealed that, despite women’s lower participation in patenting, the quality and impact of female patents were comparable to male patents, suggesting commercial science may be missing out on opportunities to generate value by failing to address disparities in patenting support. In a later study, Whittington and Smith-DoerrFootnote 157 examined detailed data from a sample of academic and industrial life scientists working in the United States. This highlighted the role of organisational settings in influencing gender disparities, suggesting that less bureaucratic and horizontal work relations might favour better female participation.

In their statistical study on the U.S. 2003 National Survey of College Graduates, Hunt et al.Footnote 158 explained the gender gap in terms of women’s underrepresentation in engineering, development, and design occupations.

Sugimoto et al.Footnote 159 used 4.6 million utility patents issued by the United States Patent and Trade Office (USPTO) between 1976 and 2013. They found that the female-to-male ratio of patenting activity increased from 2.7% to 10.8% during that period, with female patentees primarily originating from academic institutions.

However, there are few studies analysing the gender patenting gap in Europe and Ibero-America.

Busolt and KugeleFootnote 160 conveyed that female participation ranged from 5% to 25% in European Union Member States, with a significant disparity between female academic production and patent output, indicating that women inventors’ potential is underutilised.

For the period 1990–2006, Morales and SifontesFootnote 161 investigated gender differences in patenting activity in eight Latin American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Cuba, Peru, Chile, and Venezuela. According to data from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), female inventors account for 20% of all patents. The countries with the most gender inequality are Peru, Mexico, and Uruguay. Finally, chemistry and metallurgy are two technological disciplines with a higher female presence.

Carvalho, Bares and SilvaFootnote 162 studied the female involvement in patent applications in 23 Ibero-American countries. The findings showed that even in more active economies like Portugal and Spain, women’s participation in patent applications does not reach 30%.

Figure 18.3 shows the evolution of share women inventors in the period 2004–2018. Despite an encouraging record high of 17% of applications coming from female inventors in 2018, the numbers demonstrate that a large gender disparity still exists (Fig. 18.3). According to Hosler,Footnote 163 gender equality in invention was more than 75 years away.

7 Conclusion

The chapter has attempted to shed light on gender equality from an economic and managerial perspective. Feminist economics has been conceptualised and framed in comparison with mainstream economics, showing how macroeconomic policy produces and reproduces differential opportunities for women and men and further genders. From raising political critique on the division of private and public, theoretical critique of the notion of ‘economic man’, to human rights-based critique towards the unequal division of unpaid care work, feminist economics has developed to become an academic field and institutionalised discipline in its own right. The main lines of critique of mainstream economics include: (1) majority men, or the norm group of men and their interests and concerns, underlie economists’ concentration on markets, consequently leaving women’s household activities and unpaid care work unrecognised; (2) the emphasis on individual choice and autonomy, rendering social and economic inequalities and their constraints/limitations on choice unrecognised; and (3) the focus on (some) men’s interests has created bias in the definition and boundaries of the discipline, its central assumptions, its choice and acceptance of methods, and its results. This bias, produces theories and knowledge that have excluded the knowledge and experiences of women, may therefore not be valid. As it has been argued in the chapter, a main conclusion is that a focus on gender economics, and putting it into practice, has the potential to address and contribute to the solution to some of the most pressing contemporary social, economic, and environmental concerns.

The main gender indicators, their sources and databases have been presented in order to provide the necessary tools for students to learn how to analyse data from a gender perspective. These indicators have shown that the Baltic countries are the most gender equal. The functioning of the labour market has also been analysed from a gender perspective and the consequences that digitalisation can have on gender equality have been indicated.

Gender mainstreaming was identified as a relevant approach for promoting gender equality and combatting discrimination. It consists of the integration of gender perspective into policy making, real-life facets and manifestations. Key features of gender mainstreaming are women’s equal representation in any societal aspect, and the inclusion of gendered issue within policy contents. However, alongside regulations and principle’s statements, what matters is how they can be put into practice.

Thus, managerial concepts and tools used to operationalise gender mainstreaming within both private and public sectors are considered, adopting Corporate Social Responsibility as a general framework. For educational reasons, public and private actors gendered policies’ design and implementation have been treated separately. However, it has been recognized that these two worlds are interrelated; the put-in-action of gender mainstreaming requires the adoption of a multidimensional notion of performance, not just focused on financial results, but also on environmental and social ones. Consequently, the profile of gender responsive companies is identified, characterised by female directors and/or organisational welfare systems fostering the balance between work and family life.

Codes of ethics, sustainability reports, gender-responsive policy design and public budgeting are described as valuable managerial tools for triggering gender equality in organisations. However, their effectiveness is not fully realisable without educational interventions aimed at stimulating motivational forces, going beyond the mere rule-compliance logic.

Finally, gender inequality in Science, Technology, and Innovation should be the focus of public policies, being better equipped to access up-to-date regional data on the evolution of gender inequalities, and the outcomes of current and previous attempts to minimise them. Offering financial aid with patenting fees, promoting women’s participation in STEM fields, and enhancing business networking are just a few of policy ideas.Footnote 164

Questions

-

1.

What are the main lines of feminist critique of mainstream economics?

-

2.

What is homo economicus?

-

3.

Describe the gendered division of labour in the market economy and how the market economy could be reconsidered from a gender perspective?

-

4.

Identify three European countries whose gender indicators show greater equality between men and women. Justify your answer.

-

5.

Select three gender indicators related to the labour market in European countries and analyse their 2020 values.

-

6.

What are the main factors causing feminist socioeconomic inequalities in work and employment?

-

7.

What is Corporate Social Responsibility? How is gender related to it?

-

8.

How is it possible to incorporate the gender perspective into public budgets?

-

9.

Based on your own opinion, what are the main causes of the gender patenting gap?

-

10.

How many female inventors do you know? What are their inventions?

Notes

- 1.

Becchio (2019).

- 2.

Boehnert (2019).

- 3.

- 4.

Agarwal (1997).

- 5.

OECD (2021). OECD.Stat. Employment: Time spent in paid and unpaid work, by sex.

- 6.

Walby (1990), pp. 91–104.

- 7.

Chesley and Flood (2017).

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

Nelson and Ferber (2003).

- 11.

Mill (2007).

- 12.

Piketty (2014).

- 13.

Morgan (2009).

- 14.

Strid et al. (2013).

- 15.

Bjørnholt and McKay (2014).

- 16.

Feminist economics’ interactions with ecological economics is an emerging academic field, with potential analytical synergies using degrowth and placing the care society at the center of analysis (Dengler and Strunk 2017).

- 17.

Ferber and Nelson (1993).

- 18.

Bauer (1966).

- 19.

Land (1971).

- 20.

EIGE (2020).

- 21.

Ibid.

- 22.

Ibid.

- 23.

EIGE (2013).

- 24.

Papadimitriou et al. (2020).

- 25.

Richie et al. (2020).

- 26.

- 27.

- 28.

Hausmann et al. (2006), p. 5.

- 29.

Ibid.

- 30.

- 31.

- 32.

- 33.

- 34.

- 35.

- 36.

- 37.

OECD (2021).

- 38.

Grimshaw et al. (2017), p. 6.

- 39.

Schanzenbach and Nunn (2017).

- 40.

Frey and Osborne (2017).

- 41.

Ţiţan et al. (2014).

- 42.

European Commission (2020).

- 43.

Krieger-Boden and Sorgner (2018).

- 44.

- 45.

World Economic Forum (2016).

- 46.

“This indicator is broken down by age group and it is measured as a percentage of each age group” (OECD 2021). Labour force participation rate = labour forcetotal working age population (15–64)

- 47.

OECD (2021).

- 48.

Eberharter (2001).

- 49.

Sasaki (2002).

- 50.

Mazzocco et al. (2014).

- 51.

Moeeni (2021).

- 52.

- 53.

Nadeem et al. (2020).

- 54.

- 55.

Apostolopoulos et al. (2018).

- 56.

Moore (1995).

- 57.

Leuenberger (2006).

- 58.

Hughes (2003).

- 59.

Hood (1991).

- 60.

Rhodes (1996).

- 61.

- 62.

Stoker (2006).

- 63.

European Commission (2001).

- 64.

European Commission (2002).

- 65.

Celma et al. (2014).

- 66.

Garrica and Melè (2004).

- 67.

Mohr et al. (2001).

- 68.

European Commission (2001).

- 69.

Coda (2012).

- 70.

Ibid., p. 73.

- 71.

Porter and Kramer (2006).

- 72.

Turban and Greening (2017).

- 73.

Luo and Bhattacharya (2009).

- 74.

Bhattacharya and Sen (2004).

- 75.

- 76.

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987).

- 77.

Apostolopoulos et al. (2018).

- 78.

Elkington (1997).

- 79.

Tullberg (2012).

- 80.

Friedman (1970).

- 81.

Freeman (1984).

- 82.

Gennari (2018).

- 83.

SustainAbility (2018), p. 4.

- 84.

Bonn and Fisher (2011).

- 85.

Mason and Simmons (2014).

- 86.

- 87.

Earley and Mosakowski (2000).

- 88.

Pletzer et al. (2015).

- 89.

Liao et al. (2015).

- 90.

Ben-Amar et al. (2017).

- 91.

Haque (2017).

- 92.

De Masi et al. (2021).

- 93.

Ibid., p. 1866.

- 94.

Valls Martínez et al. (2020).

- 95.

Eagly et al. (2003).

- 96.

Pfeffer (1972).

- 97.

Scherer and Palazzo (2007).

- 98.

Gennari (2018).

- 99.

Jensen and Meckling (1976).

- 100.

Adams and Ferreira (2009).

- 101.

Freeman (1984).

- 102.

Francoeur et al. (2019).

- 103.

See also the business law chapter of this book for the legal provisions.

- 104.

Hill and Jones (1992).

- 105.

Pulejo (2011).

- 106.

- 107.

Perry-Smith and Blum (2000).

- 108.

Pulejo (2011), p. 60.

- 109.

European Commission (2011).

- 110.

Ibid.

- 111.

Ibid.

- 112.

- 113.

Testa et al. (2018b).

- 114.

Testa et al. (2018a).

- 115.

Ibid., pp. 853–854.

- 116.

Valls Martínez et al. (2020).

- 117.

- 118.

Adams and Simmet (2011).

- 119.

Eccles and Saltzman (2011).

- 120.

Stoker (2006).

- 121.

Moore (1995).

- 122.

Meier et al. (2006).

- 123.

Rosener (1990).

- 124.

- 125.

- 126.

- 127.

Ibid.

- 128.

Guy and Newman (2004).

- 129.

Meier et al. (2006).

- 130.

Rubin and Bartle (2005).

- 131.

Ibid., p. 259.

- 132.

Budlender and Hewitt (2002).

- 133.

United Nations (1979).

- 134.

United Nations (1995).

- 135.

Council of the European Union (2006).

- 136.

Pulejo (2011).

- 137.

Ibid., p. 260.

- 138.

- 139.

Budlender and Hewitt (2002).

- 140.

Rubin and Bartle (2005).

- 141.

Ibid., p. 269.

- 142.

Ibid., p. 264.

- 143.

Ibid., p. 264.

- 144.

Ibid., p. 264.

- 145.

Ibid., p. 264.

- 146.

Ibid., p. 264.

- 147.

Ibid., p. 269.

- 148.

Ibid., p. 269.

- 149.

OECD and Eurostat (2018).

- 150.

World Intellectual Property Organization. “What Is Intellectual Property (IP)?”

- 151.

World Intellectual Property Organization. “Innovation and Intellectual Property”.

- 152.

European Patent Office, “Glossary”.

- 153.

Larivière et al. (2013).

- 154.

Frietsch et al. (2009).

- 155.

Murray and Graham (2007).

- 156.

Whittington and Smith-Doerr (2005).

- 157.

Whittington and Smith-Doerr (2008).

- 158.

Hunt et al. (2013).

- 159.

Sugimoto et al. (2015).

- 160.

Busolt and Kugele (2009).

- 161.

Morales and Sifontes (2014).

- 162.

Carvalho et al. (2020).

- 163.

Hosler (2018).

- 164.

Milli et al. (2016).

References

Adams RB, Ferreira D (2009) Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J Financ Econ 94:291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

Adams S, Simmet R (2011) Integrated reporting: an opportunity for Australia’s not-for-profit sector. Aust Account Rev 58:292–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-2561.2011.00143.x

Agarwal B (1997) Bargaining’ and gender relations: within and beyond the household. Fem Econ 3:1–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457097338799

Apostolopoulos N, Al-Dajani H, Holt D et al (2018) Entrepreneurship and the sustainable development goals. Contemp Issues Entrep Res 8:1–7

Arrive JT, Feng M (2018) Corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from BRICS nations. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 25:920–927. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1508

Bàez AB, Bàez-Garcìa AJ, Flores-Munoz F et al (2018) Gender diversity, corporate governance and firm behavior: the challenge of emotional management. Eur Res Manag Bus Econ 24:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2018.07.001

Barnett K, Grown C (2004) Gender impacts of government revenue collection—the case of taxation. Commonwealth Secretariat, London

Bauer RA (1966) Social indicators and sample surveys. Public Opin Q 30:339–352

Becchio G (2019) A history of feminist and gender economics. Routledge, London

Ben-Amar W, Chang M, McIlkenny P (2017) Board gender diversity and corporate response to sustainability initiatives: evidence from the Carbon Disclosure Project. J Bus Ethics 142:369–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2759-1

Bhattacharya CB, Sen S (2004) Doing better at doing good: when, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif Manag Rev 47:9–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166284

Bjørnholt M, McKay A (2014) Counting on Marilyn Waring: new advances in feminist economics. Demeter Press, Toronto

Boehnert J (2019) Anthropocene economics and design: heterodox economics for design transitions. She Ji: J Des Econ Innov 4:355–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2018.10.002

Bonn I, Fisher J (2011) Sustainability: the missing ingredient in strategy. J Bus Strateg 32:5–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/02756661111100274

Celma D, Martínez-Garcia E, Coenders G (2014) Corporate social responsibility in human resource management: an analysis of common practices and their determinants in Spain. Corp Soc Respon Environ Manag 21:82–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1301

Chesley N, Flood S (2017) Signs of change? At-home and breadwinner parents’ housework and child-care time. J Marriage Fam 79:511–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12376

Coda V (2012) The evaluation of the entrepreneurial formula. Eur Manag Rev 9:63–74

Council of the European Union (2006) Presidency conclusions of the Brussels European Council, 23/24 March 2006, 7775/1/06 REV 1. Annex II, European pact for gender equality. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7775-2006-REV-1/en/pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2021

Crenshaw K (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum 1989:139–167

Crompton R (2006) Employment and the family: the reconfiguration of work and family life in contemporary societies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

De Masi S, Słomka-Gołębiowska A, Becagli C, Paci A (2021) Toward sustainable corporate behavior: the effect of the critical mass of female directors on environmental, social, and governance disclosure. Bus Strateg Environ 30:1865–1878. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2721

Budlender D, Hewitt G (2002) Gender budgets make more cents: country studies and good practices. Commonwealth Secretariat, London

Dierkes M, Peterson A (1997) The usefulness and use of social reporting information. Acc Organ Soc 10:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(85)90029-7

Duerst-Lahti G, Johnson CM (1990) Gender and style in bureaucracy. Women Polit 10:67–120

Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC, van Engen ML (2003) Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull 129:569–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.569

Earley CP, Mosakowski E (2000) Creating hybrid team cultures: an empirical test of transnational team functioning. Acad Manag J 43:26–49

Eberharter V (2001) Gender roles, labour market participation and household income position. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 12:235–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0954-349X(01)00021-2

Eby LT, Casper WJ, Lockwood A et al (2005) Work and family research in IO/OB: content analysis and review of the literature (1980-2002). J Vocat Behav 66:124–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.003

Eccles RG, Saltzman D (2011) Achieving sustainability through integrated reporting. Stanf Soc Innov Rev 9:57–61

EIGE (2013) Gender equality index: main findings. European Institute for Gender Equality, Vilnius

EIGE (2020) Glossary & thesaurus. European Institute for Gender Equality, Vilnius. https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1195. Accessed 29 Oct 2021

Elkington J (1997) Cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21th century business. Capstone Publishing, Oxford

Elson D (1999) Gender-neutral, gender-blind, or gender-sensitive budgets? Changing the conceptual framework to include women’s empowerment and the economy of care. Gender Budget Initiative Background Papers. Commonwealth Secretariat, London

European Commission (2001) Green paper – promoting a European framework for corporate social responsibility. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2001/EN/1-2001-366-EN-1-0.Pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2021

European Commission (2002) Communication from the Commission concerning corporate social responsibility: a business contribution to sustainable development. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6e2c6d26-d1f6-48a3-9a78-f0ff2dc21aad/language-en. Accessed 29 Oct 2021

European Commission (2011) A renewed EU strategy 2011–14 for corporate social responsibility. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52011DC0681. Accessed 29 Oct 2021

European Commission (2020) Proposal for a Joint Employment Report 2021: text proposed by the European Commission on 18 November 2020 for adoption by the EPSCO Council. European Union, Brussels

European Patent Office. Glossary. https://www.epo.org/service-support/glossary.html. Accessed 29 October 2021.

Ferber MA, Nelson JA (1993) Beyond economic man: feminist theory and economics. Chicago University Press, Chicago