Abstract

Social enterprise can be described as a complex and variegated phenomenon marked by different extensions and definitions according to the legal system of reference. This contribution is focused on a specific area of the social enterprise spectrum, that of the hybrid dual-purpose businesses, conceiving social enterprises as private organisations that carry out commercial activities to pursue social and environmental, as well as economic, objectives. In the past few decades, several legal systems have introduced new hybrid entities designed to adequately meet the needs of social entrepreneurs and capable of bringing together social and environmental aims with business approaches. The birth of social enterprise, with the introduction of philanthropic goals into the articles of association’s corporate purpose clause, is particularly difficult to understand through the lenses of the economic analysis of law or the neoclassical economics and its homo economicus paradigm. This study attempts to offer an interpretative key for understanding these hybrid models abandoning the classical homo economicus paradigm to embrace a reading based on behavioural law and economics and the Yale approach to the economic analysis of law, according to which altruism and beneficence should be considered as ends in themselves, as goods desired by people and for which they are willing to pay the price. In this line of reasoning, social enterprises, as a bottom-up phenomenon are the legislator’s policy response to the growing demand for firm altruism emerging from civil society.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: Definition of Social Enterprise

Social enterprise (SE) can be described as a complex and variegated phenomenon marked by different extensions and connotations according to the legal system of reference. The definitions of social enterprise indeed are numerous and differently characterised in the various legal systems.Footnote 1 For example, with regard to the countries belonging to the Western legal tradition, Europe and the United States have different approaches towards SE.Footnote 2

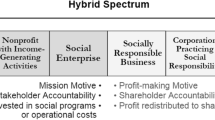

In Europe, social enterprise is traditionally considered an alternative to charities,Footnote 3 while the United States has embraced a broader view of SE, including profit-oriented businesses organisations involved in socially beneficial activities, hybrid dual-purpose businesses mediating profit goals with social objectives, and non-profit organisations engaged in mission-supporting commercial activity.Footnote 4 However, from a general perspective, it is possible to identify a common element characterising social enterprises regardless of the legal structure used, namely, the positive impact generated by the entity in the territory and the community in which it operates, through the creation of positive externalities or the reduction of negative externalities.

In this contribution, a broad definition of SE is accepted. Moving from such broader definition, the focus will be on a specific area of the social enterprise spectrum, that of the hybrid dual-purpose businesses, thus conceiving social enterprises as private organisations, particularly profit-making companies, that carry out commercial activities—with an economic method—to pursue economic, as well as social and environmental objectives.Footnote 5 Companies with a double (or blended) purpose, profit-making and “common benefit”, operating in accordance with the so-called “triple bottom line” scheme (the 3P scheme, regarding people, planet, profit), which takes into consideration the social, environmental, and economic result of the company.Footnote 6

2 The Evolution of Social Enterprise Hybrid Legal Forms: A Comparative Law Perspective

From a legal perspective, the development of laws aimed at regulating social enterprises is related to the debate on the use of existing entities, particularly for-profit legal structures, for the conduct of “hybrid” (profit and non-profit) businesses.

Some legal systems, such as the United States, Germany, and Switzerland, do not have problems of systematic interpretation related to the logical coherency of the system itself in the use of for-profit structures by social enterprises because they generally allow the use of the business structures (e.g., corporations/companies limited by shares, or limited liability companies) for non-profit activities. Other legal systems, such as France and Italy,Footnote 7 provide for the use of for-profit structures mainly (unless specific exceptions are prescribed for by law) for the pursuit of profit-making purposes (although business companies may seek social benefit, e.g., through philanthropy or other corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities,Footnote 8 not as their primary objective but as a secondary and eventual objective), and reserve other legal forms (i.e., non-profit legal forms) such as associations and foundations for philanthropic activities.

However, a significant body of scholarship and business leaders argue that the existing for-profit entities, also in countries allowing their use for hybrid purposes, are not sufficient for the development of the modern social enterprise sector.Footnote 9 The most relevant issues about the use of for-profit organisations concern: i) the safeguarding of the “fidelity to the mission” following a change of control,Footnote 10 and ii) the predominance of the shareholder wealth maximisation principle as a parameter that directors must consider in their decisions, to avoid claims for breach of fiduciary duties.Footnote 11

To overcome all these limitations and the dissatisfaction with the for-profit/not-for-profit dichotomy, in the past few decades, several legal systems from the Americas to Europe, have introduced new hybrid entities designed to adequately meet the needs of social entrepreneurs and capable of bringing together social and environmental aims with business approaches.

Since the 1980s, the United States has experienced rapid growth in the modern SE movement with the proliferation of new hybrid forms, such as the low-profit limited liability company (L3C)Footnote 12 introduced for the first time in Vermont in 2008,Footnote 13 the social purpose corporation (SPC) introduced in California in 2011 (formerly known as the flexible purpose corporation),Footnote 14 and the benefit corporation introduced in Maryland in 2010.Footnote 15 The latter is reflected in a more comprehensive model legislation (the Model Benefit Corporation Legislation – Model ActFootnote 16), and currently implemented by 36 states plus Washington DC and Puerto Rico.Footnote 17 In North America, British Columbia – Canada, followed the U.S. example introducing the “benefit companies” in 2020.Footnote 18

With regard to Europe, sustainable development has long been at the heart of the European project, but European countries and Institutions have long adhered to a narrow view of the social enterprise, considering it as a synonym for charitable activities rather than a genuine blended-value enterprise.Footnote 19 As a result, the social enterprise movement in Europe is mainly focused on the development of third sector services, on areas from which the welfare state had retreated, and operates through non-profit associations, foundations, or cooperatives, which are generally characterised by the non-distribution constraint.Footnote 20

A different approach has been taken by the United Kingdom, which in 2004 introduced a new hybrid model specifically designed for SE, the “community interest company” (CIC), consistent with the evolution of the SE movement towards blended enterprises aimed at pursuing social and environmental goals as well as generating shareholder wealth.Footnote 21 CICs represent the first step towards a new blended-value entity, but they have as primary purpose the pursuit of social and environmental objectives and are characterised by limits to the distribution of dividends.

From this perspective, the most innovative legal structure introduced in Europe in 2016 is the Italian “società benefit” (SB), which is the legal transplant of the U.S. benefit corporation.Footnote 22 A few years later, in 2019, also France, going further the development of the “Économie Sociale et Solidaire”,Footnote 23 introduced a new hybrid legal status similar to that of the benefit corporation, the “entreprise à mission”, allowing for-profit companies to incorporate social and environmental aims into their corporate purpose.Footnote 24

Latin American countries are also exploring new models of growth that focuses not solely on making profits but also on a social and environmental mission.Footnote 25 A legal model designed for SE is pending introduction in several states, such as ArgentinaFootnote 26 and Chile,Footnote 27 while, between 2018 and 2020, benefit corporations have been transplanted in Colombia,Footnote 28 EcuadorFootnote 29 and PerùFootnote 30 through the introduction of the “Sociedades de Beneficio e Interés Colectivo” (BICs).

Finally, the spread of new hybrid legal structures also reached the African continent. At the beginning of 2021 in fact, Rwanda passed the benefit corporation legislation introducing the so-called “community benefit company” and becoming the 7th country in the world to provide this option.Footnote 31

3 Philanthropic Purposes and For-profit Corporation

Observing the convergence of the legal systems in the implementation of hybrid entities statutes to support the development of SE one wonders why in the context of the for-profit sector, traditionally characterised by a self-interest purpose (materialised in the maximisation of profits and their distribution to the shareholders), the need has been felt to introduce altruistic or philanthropic aims right into the articles of association’s corporate purpose clause.Footnote 32

It is particularly difficult to find an answer analysing the phenomenon through the inflexible lenses of the economic analysis of law (EAL) or the neoclassical economics and its homo economicus paradigm, according to which human beings are rational and selfish actors, focused entirely on maximising their own material well-being.Footnote 33 Once accepted the rational choice theoryFootnote 34 indeed, appears to be difficult to justify those human conducts led by altruistic and disinterested behaviours (such as the inclusion of altruistic purposes within the corporate purpose of business companies).

Nonetheless, the observation of the reality shows that the unselfish prosocial behaviour is very common in human social life (as also demonstrated by several social dilemma experiments),Footnote 35 suggesting the need for re-thinking the behavioural paradigm of the homo economicus that is not apt to explain inclination towards altruism and cooperation that is, to the contrary, a fundamental and universal aspect of human behaviour, as much as selfish conduct and the pursuit of material well-being.Footnote 36

In this sense, new behavioural models suitable for explaining the physical and juridical world can be found both in the studies of Behavioural Law and Economics (aimed at highlighting the cognitive variables within the decision-making processes of individualsFootnote 37 and the reasons underlying human behavioursFootnote 38), as well as in the “multi-faceted approach” to juridical phenomena that is typical of the Yale School of economic analysis of law (the so-called “Law & Economics”).Footnote 39

Regarding this latter, an impressive starting point for the reconstruction of the phenomena of altruism and beneficence, useful for our purposes, is offered by a recent contribution of Guido Calabresi.Footnote 40 According to the author, altruism, beneficence, and similar values exist in the empirical reality not simply as “means” for the production of other goods and services, but also because they constitute “ends in themselves”, they are desired as “goods in and of themselves” to satisfy the desire of which individuals are willing to pay a price.Footnote 41

Using the arguments employed by Calabresi, hybrid entities (or SEs), although apparently in contrast with the concept of maximising individual, are therefore made logical when considered as the products of a new way of interpreting economics, in which the purposes, selfish (profit-making) and altruistic (public benefit), are both desired by the shareholders as goods in and of themselves. Both purposes enter the company’s articles of association and by-laws, legitimising the pursuit of business strategies that can turn out to be less profitable in terms of immediate profit and maximisation of wealth for the shareholder,Footnote 42 but also capable of generating wealth to be shared with the community and the territory. Hence, if we look at the public benefit purpose pursued by social enterprises as a good in and of itself, desired by members/shareholders, the social enterprise model cannot be deemed irrational merely because it does not correspond to the behavioural model of the homo economicus.

In his analysis of altruism, beneficence, and non-profit institutions, Calabresi also underlines how the individuals’ need for altruism as good in and of itselfFootnote 43 shows in several forms: the desire of individual altruistic behaviors’ (private altruism), altruistic behaviours by the State (public altruism) and altruistic behaviours by private firms (firm altruism). In this last case, it can show both as non-profit companies and as philanthropic activity undertaken by for-profit companies.Footnote 44

From the perspective of for-profit companies, traditionally, the answer to the request for firm altruism was embodied in “corporate philanthropy” activities and programmes, thus supporting beneficial causes and achieving a positive social impact through contributions in cash or in kind. But using the categories employed by Calabresi, it can be affirmed that social enterprise constitute a further manifestation of firm altruism, more efficient (from a law and economic perspective) than the not-for-profit organisations, because devoid of the limits of the nondistribution constraint, and characterised, compared to philanthropy, by a deeper and lasting impact on environment and civil society, given the integration of altruistic values within the framework of the company purpose clause contained in the articles of association.

4 Social Enterprise as a Bottom-Up Process

Social enterprise statutes are thus the new legislator’s policy response to the growing demand for firm altruism emerging from civil society. SE law indeed, can be described as a bottom-up phenomenon.

In the last decades, especially due to the financial crisis, increased inequality, ethics-based corporate scandals, and the rise of awareness on climate change’s risks, a profound reconsideration of the current economy and the capitalist system has begun, pointing out the need for a broader and deeper involvement of companies in generating a positive impact on the environment and the society. The idea of corporations not only as a tool for maximising shareholders’ profits but also as an essential means for the resolution of social and environmental problems has spread, basically increasing and strengthening the demand for firm altruism.

Nowadays, many voices are supporting the cultural transition from the shareholders’ capitalism model to a new form of stakeholders’ capitalism. Among them, for example, it is worth mentioning the proposals offered by the Catholic social doctrine through Pope Francis landmark encyclical Laudato sìFootnote 45 in which the predominant paradigm of the profit maximisation is placed in doubt in favour of an “integral ecology” (namely environmental, economic, social and cultural) aimed at the protection of the common good.Footnote 46

With regard to international institutions, the Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy adopted by the International Labour Organisation,Footnote 47 the UN Global Compact,Footnote 48 and the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)Footnote 49 can be mentioned. As far as the European Union is concerned, the call for sustainability has been supported by the Europe 2020 strategy for a smart, sustainable and inclusive growth Footnote 50 and, recently, in the context of the recovery plan following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, by the Communication Europe’s Moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation.Footnote 51

The increasing desire of firm altruism seems also confirmed by several market studies.Footnote 52 People hold companies as accountable as governments for improving the quality of their livesFootnote 53 and the improvement of society is considered the first goal that every company should pursue according to a study conducted among millennials from eighteen different countries.Footnote 54 Regarding consumers, a growing number already aligns its purchases with its values and consider sustainability in its purchasing decisions.Footnote 55

Investors as well, are increasingly interested in financing socially conscious businesses, see e.g., the BlackRock statement of February 2019 on sustainability as the future of investing.Footnote 56 This contributed to the growth of the socially responsible investing (SRI) movement,Footnote 57 the emergence of specific stock markets (i.e., Social Stock Exchanges) and indices (e.g., the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices and the Financial Times Stock Exchange 4Good), as well as the development of ESG criteria (with reference to environmental, social and governance) and sustainability assessment tools (such as the Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIIRS), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards, or the “B Corp” certification issued by B Lab).

Even in the labour market, an additional value is recognised by students and employees to companies that can make a positive social and environmental impact.Footnote 58

Moreover, in the last years, the debate about corporate purpose and the “problem of shareholder primacy” has intensified among legal academics and business scholars,Footnote 59 and the relevance of firm altruism has been recognised also by the business community. In 2018, BlackRock CEO, Larry Fink, called for companies, together with delivering financial performance, to pursue a “social purpose”, a positive contribution to society. Footnote 60 While in August 2019, nearly 200 CEOs representing the largest U.S. companies that are members of the Business Roundtable released a “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation”, which moves away from shareholder primacy and includes a fundamental commitment to all of a company’s stakeholders. Footnote 61

The answer of the law to this strong demand for firm altruism coming from the civil society has been the introduction of new hybrid organisational forms suitable for the social enterprise and characterised by a governance structure appropriate for incorporating within the decision-making process altruism as good in and of itself, as a new company purpose equivalent and complementary to the profit-making purpose.

The hybrid forms regulated by the legislators in the various legal systems can be characterised by different features due to path dependency but is possible to identify a certain level of convergence on issues such as the dual company purpose,Footnote 62 new duties of conduct for directorsFootnote 63 and disclosure requirements.Footnote 64 This convergence is due to the circulation of legal models, particularly that of the U.S. benefit corporation, and to the actual global dimension of markets and economies.

5 New Challenges for the Social Enterprise

The spread of the social enterprise phenomenon and the hybridisation process of business companies’ purpose has given new life to the old debate on the nature and the purpose of the corporationFootnote 65 (and, generally, of for-profit entities). The emergence of new hybrid entities together with the growing awareness of the risks of climate change and the role of sustainability in businesses has led to an evolution of corporate and financial law towards the acceptance of the environmental and philanthropic dimensions.

An example can be offered by the European Union path in the harmonisation of company law that over recent years seems to have opened to a more comprehensive protection of stakeholders’ interests in for-profit entities, almost bringing traditional business companies closer to the social enterprise model.

The growing importance of sustainability and its perception as an added value for profit-making companies triggered an intense activity of revisioning and updating the European rules applicable to financial markets and company law. From an initial promotion of voluntary CSR programmes through the development of soft law instruments such as the European Strategy on Corporate Social Responsibility,Footnote 66 the focus has been shifted to the introduction of mandatory rules requiring the adoption of sustainable business practices. Among them, the Directive on non-financial reporting,Footnote 67 the Directive on long term shareholder engagement,Footnote 68 the Regulation on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector,Footnote 69 and the recent Regulation on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment.Footnote 70 Moreover, a directive on corporate sustainability reporting,Footnote 71 a directive on supply chain due diligence,Footnote 72 and a directive on directors’ duties and sustainable corporate governanceFootnote 73 are currently under consideration by the EU institutions.

Given the global nature of markets, it is possible to identify two new challenges that the social enterprise will have to face, i.e., the harmonisation of SE organisational forms, and the relevance and comparability of impact assessment metrics.

The first concerns the utility of some forms of unification or harmonisation of the fourth sector organisational forms, the social enterprise sector, in which firms integrate social and environmental purposes with the business method. From the international perspective, the unification/harmonisation of domestic regulation of hybrid companies can help foster a common approach for the development of a strong fourth sector, thus increasing trust and facilitating cross-border investment and trading within the sector itself. From the domestic law perspective, the introduction of a well-known and recognised international hybrid entity model may play an important role in the development of a domestic fourth sector and in enhancing the credibility and branding aspect of these companies in a global market perspective.

The second challenge is related to the essential role of reliable impact assessment metrics and their comparability. It is essential that positive effects generated by social enterprises and communicated to third parties through periodic reports are evaluated through metrics suitable for appraising the real impact generated on several areas (such as the environment, the community, and the employees and other stakeholders) and capable of guiding firms to improve their strategy and performances. Moreover, the freedom for companies to choose the impact assessment metric to use and the global market perspective emphasise the importance and the necessity of metrics comparability. They should be recognised internationally to boost public trust in social enterprises. The large number of private standards and frameworks in existence make it difficult for the public to understand and compare companies’ results. For this reason, the trend towards a worldwide convergence and simplification and standardisation of impact assessment metrics and sustainability reporting standards must be supported and strengthened.

Notes

- 1.

See e.g., the definition of Paul Light (Light 2008), who describes SE as organisations or ventures that achieve their primary social or environmental missions using business methods, typically by operating a revenue-generating business. SE entities are entities seeking to blend the production of shareholder wealth with social and environmental goals under the umbrella of a single entity.

- 2.

- 3.

On the issue, Kerlin (2006), pp. 247–263; Esposito (2013), pp. 646–647; Defourny and Nyssens (2008), pp. 202 et seq. E.g., in Italy, the reference to “social enterprise” has a specific meaning, i.e., an entity that, according to the law, can be structured as a for-profit entity although it pursues a non-profit purpose (see D.Lgs. 24 March 2006, n. 155, now D.L. 3 July 2017, n. 112). Moreover, according to the definition developed in the UK in 2002 by the former Department of Trade and Industry, social enterprises are “a business with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximize profit for shareholders and owners” (cfr. Dep’t of Trade & Indus., Social Enterprise: A strategy for Success, 2002, p. 7).

- 4.

See the definition of Kerlin (2006), p. 248.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

Under the French and Italian Civil Codes, for profit structures can be used only to pursue profit-making activities (unless the law—D.L. 3 July 2017, n. 112—provides for specific exceptions in this regard, such as the so-called “impresa sociale” in Italy), see Art. 2247 Italian Civil Code (“Con il contratto di società due o più persone conferiscono beni o servizi per l’esercizio in comune di una attività economica allo scopo di dividerne gli utili.”) and Art. 1832 French Civil Code (“La société est instituée par deux ou plusieurs personnes qui conviennent par un contrat d’affecter à une entreprise commune des biens ou leur industrie en vue de partager le bénéfice ou de profiter de l’économie qui pourra en résulter.”).

- 8.

On the issue Peter and Jacquemet (2015), pp. 170–188.

- 9.

- 10.

Following a change of corporate control, the new controller can decide to terminate the original social mission and to pursue only the profit purpose, which is the only corporate purpose provided in the articles of incorporation and bylaw of an ordinary business entity. See Cummings (2012), pp. 589–590.

- 11.

The shareholder primacy model has become the predominant model accepted by corporate law in the major legal systems belonging to the Western legal tradition (see Hansmann and Kraakman 2001, pp. 440–441, according to which “[t]here is no longer any serious competitor to the view that corporate law should principally strive to increase long-term shareholder value.”). On the shareholder primacy model, see Friedman (1970), and Jensen (2001), pp. 32–42. The shareholder primacy originates in the United States and has been first articulated by the Michigan Supreme Court in 1919 in Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. 204 Mich. 459, 170 N.W. 668 (Mich. 1919) and reaffirmed in Unocal Corp. V. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985); Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc., 506 A.2d 173, 182 (Del. 1986); Katz v. Oak Indus., 508 A.2d 873, 879 (Del. Ch. 1986); eBay Domestic Holdings, Inc. v. Newmark, 16 A.3d 1 (Del. Ch. 2010).

- 12.

L3Cs are companies aimed primarily at performing a socially beneficial (charitable or educational) purpose and not at maximising income. The L3C legal form is designed to make it easier for socially oriented businesses to attract investments from foundations, simplifying compliance with the Internal Revenue Service’s Program Related Investments’ (PRI) regulations (I.R.C. §§4944(c); 170(c)(2)(B); 26 CFR 53.4944-3(b) Ex. (3)). Indeed, thorough PRIs private foundations can satisfy their obligation under the Tax Reform Act of 1969 to distribute annually at least 5% of their assets for charitable purposes. Investments in L3Cs that qualify as PRIs can fulfil this requirement while allowing the foundations to receive a return from the investment. L3Cs have been widely criticised for their unclear regulation under tax law and did not have huge success among practitioners. See Esposito (2013), pp. 682–688; Murray (2016), pp. 545–546; Kelley (2009), p. 356.

- 13.

See Vt. Stat. Ann. Tit. 11, §3001(27). Other states such as Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Rhode Island, Utah, and Wyoming introduced the L3C statute. On L3Cs, see Lang and Carrott Minnigh (2010), p. 15.

- 14.

Then introduced in Washington in 2012, and in Florida in 2014. The SPC is a corporate entity enabling directors to consider and give weight to one or more social and environmental purposes of the corporation in decision-making. Unlike the L3C, where the charitable purpose overrides profit maximisation, the SPC give directors the discretion to choose social and environmental purposes over profits. See Esposito (2013), p. 693.

- 15.

Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns §5-6C.

- 16.

The Model Act has been proposed by B Lab with the support of William H. Clark (Of Counsel at Jr. Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP) and the American Sustainable Business Council, available at http://benefitcorp.net/sites/default/files/Model%20benefit%20corp%20legislation%20_4_17_17.pdf (accessed 4 January 2022).

- 17.

Among the U.S. states introducing benefit corporation statutes, it is worth mentioning Delaware (see Subchapter XV of the Delaware General Corporation Law (Del. Code Ann. Tit. 8, §§ 361–368).

- 18.

The Business Corporations Amendment Act (No.2) 2019 (Bill M209), which introduced benefit companies within the Busines Corporations Act (see Chapter 57, Part 2.3, §§ 51.991–51.995), received the Royal assent on May 16, 2019, and entered into force on June 30, 2020.

- 19.

Recent measures suggested by the European institutions to boost the growth of the social enterprise sector, such as the Europe 2020 Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth (Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, COM(2010) 2020, 3 March, 2010, p. 2), the Single Market Act (Single Market Act: Twelve Levers to Boost Growth and Strengthen Confidence, COM(2011) 206, 13 April, 201, pp. 24–25), and the Social Business Initiative (Social Business Initiative: Creating a Favorable Climate for Social Enterprises, Key Stakeholders in the Social Economy and Innovation, COM(2011) 682, 25 October, 2011, p. 2), continue to reflect this narrow view of the SE movement. The numerous communications released by the European Commission suggest the creation of a comprehensive European legal framework to promote the development of the SE sector and facilitate investments in these enterprises at a European level. Moreover, the Commission suggests reforming the statute of the European Cooperative Society considering that many social enterprises operate in the form of social cooperatives. Thus, the European Commission focused the development of an organisational form characterised by the non-distribution constraint with limits on the distribution of profits. On this issue, see Esposito (2013), pp. 679–680.

- 20.

- 21.

See Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act, 2004, c. 27, §26. CICs are blended legal structures (companies limited by guarantee or companies limited by shares) for businesses that primarily have social and environmental objectives and whose surpluses are principally reinvested in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders. CICs can raise equity capital as for-profit companies but at the same time their use ensure that company’s assets are dedicated to public benefit. Thus, the distribution of dividends is capped at 35% of the aggregate total company profits (Office of the Regulator of Community Interest Companies, Community interest companies: guidance chapters, Chapter 6: The asset Look, pp. 6 et seq.) and, in the event of dissolution, CICs’ assets must go to similar entities pursuing community benefits. Moreover, CICs are overseen by the CIC Regulator, which ensures compliance with the “community interest test” (verifying, according to the Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act, 2004, c. 27, §35(2), that CIC’s activity is carried on for the benefit of the community) and receives the CIC’s annual report. It is worth noting that CICs do not have tax advantages and are subject to the corporation tax regime. In legal literature, see Lloyd (2010), p. 31; Esposito (2013), pp. 674–678.

- 22.

Law No. 208 of December 28, 2015, “Disposizioni per la formazione del bilancio annuale e pluriennale dello Stato (Legge di Stabilità 2016)” Art. 1, paragraphs 376–384.

- 23.

Law No. 2014-856 of July 31, 2014. The “Économie Sociale et Solidaire” (ESS) (literally, Social and Solidarity Economy) encompasses all the entities whose status, organisation and activity are based on the principles of solidarity, equity and social utility. The ESS is composed of not-for-profit and for-profit structures. SSE entities adopt participative and democratic governance mechanisms and are characterised by strict limitations to the distribution of profits.

- 24.

Law No. 2019-486 of May 22, 2019, Art. 169. See the amendment to Civil Code Arts. 1833 and 1835, and French Commercial Code, Arts. L. 225-35, L. 225-64, L. 210-10, L. 210-11. To acquire the status of entreprise à mission the articles of association of a for-profit company must specify the peculiar raison d’être of the company and one or more social and environmental purposes that the company want to pursue in the framework of its activity. Moreover, the publication of an annual report on the company’s social mission assessed against an independent third-party standard, and the creation of a special committee (“comité de mission” or “référent de mission”) separate from the other corporate bodies, which is exclusively responsible for monitoring and reporting the pursuit of the social mission is required.

- 25.

On the issue, see Alcalde Silva (2018), pp. 381–425.

- 26.

See Bill No. 2498-D-2018, approved by the Cámara de Diputados in December 2018, which is pending approval in the Senado.

- 27.

Bill No. 11273-03, of May 2017.

- 28.

Law No. 1901, of June 8, 2018.

- 29.

See the Resolution of the Superintendencia de Compañías, Valores y Seguros No. SCVS-INC-DNCDN-2019-0021, of December 6, 2019, and Law January 7, 2020 (so-called “Ley Orgánica de Emprendimiento e Innovación”), published in the Registro Oficial Suplemento No. 151, of 28 February 2020.

- 30.

The Bill No. 2533/2017-CR, so-called Ley de Sociedades de Beneficio e Interés Colectivo, has been approved on October 23, 2020 by Congreso de la República.

- 31.

See Chapter XIII “Community Benefit Company”, Articles 269–273 of Law N° 007/2021, of 5 February 2021 (Official Gazette n° 04 ter of 08/02/2021).

- 32.

On this issue Ventura (2018), pp. 545–590.

- 33.

On the homo economicus model Stout (2014), pp. 195–212.

- 34.

- 35.

Stout (2014), pp. 198–200.

- 36.

- 37.

See the studies by Simon (1955), pp. 99 et seq.; Simon (1957), pp. 270 et seq.; Kahneman and Tversky (1974), pp. 1124 et seq.; Kahneman and Tversky (1984), pp. 341 et seq.; Kahneman (2011). In general, on Behavioral Law and Economics, see Thaler (1996), pp. 227 et seq.; Sunstein (1997), pp. 1175 et seq.; Sunstein et al. (1998), pp. 1471 et seq.; Korobkin and Ulen (2000), pp. 1051 et seq.; Sunstein (2000); Parisi and Smith (2005); Thaler and Sunstein (2008); Zamir and Teichman (2014).

- 38.

- 39.

In addition to the volume by Calabresi (2016), for a description of the approaches to the economic analysis of law of the two schools of Yale (of Law & Economics)—using economics to understand the law as it is in the reality—and of Chicago (Economic Analysis of Law)—using the economic paradigms to adjust the law, identifying the best choices in terms of efficiency, according to Pareto optimality—see the contribution of Alpa (2016), pp. 599–601.

- 40.

Calabresi (2016), pp. 90–116.

- 41.

Calabresi (2016), pp. 90–91.

- 42.

For a summary of the several advantages, also economic, that a corporation can derive from good reputation in terms of social and environmental sustainability, see Monoriti and Ventura (2017), pp. 1125–1128.

- 43.

It must be specified that according to Calabresi altruism does not constitute a single good, rather it constitutes a group of interrelated goods that can be placed on different levels: altruism as means—replaceable—for the production of other desired goods; and the altruism as end and good in and of itself, only partially replaceable depending on the type of desired altruism (private, public, or firm altruism), see Calabresi (2016), pp. 94, 98 et seq.

- 44.

Calabresi (2016), pp. 93–94.

- 45.

Laudato sì - Enciclica sulla cura della casa comune, 24 May 2015, Pope Francis, Italian edition Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, 2015.

- 46.

On the Encyclica Laudato sì, see also Toffoletto (2015), pp. 1203 et seq.

- 47.

Adopted by the Governing Body of the International Labour Office at its 204th Session (Geneva, November 1977) and amended at its 279th (November 2000), 295th (March 2006) and 329th (March 2017) Sessions.

- 48.

The UN Global Compact was officially launched at UN Headquarter in New York City on 26 July 2000.

- 49.

See A/RES/70/1, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, launched by a UN Summit in New York on 25–27 September 2015.

- 50.

Commission Communication of 3 March 2010 on “Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth”, COM(2010) 2020.

- 51.

Commission Communication of 27 May 2020 on “Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation”, COM(2020) 456.

- 52.

See, among others, Ernst & Young, Climate Change and Sustainability: Seven Questions CEOs and Boards Should Ask About “Triple Bottom Line” Reporting (2010), pp. 7–9; The 2010 Cone Cause Evolution Study, available at https://www.conecomm.com/2010-cone-communications-cause-evolution-study-pdf (accessed 4 January 2022). Among scholars, see Grant (2012), pp. 591–597; Kerr (2008), pp. 832 et seq.; Jackson (2010), pp. 92 et seq.

- 53.

See Accenture, Havas Media RE:PURPOSE, The Consumer Study: From Marketing to Mattering, The UN Global Compact-Accenture CEO Study on Sustainability, available at https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:2tvcvHIRST4J:https://sustainability.glos.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Accenture-Consumer-Study-Marketing-Mattering-2.pdf+&cd=1&hl=it&ct=clnk&gl=it&client=firefox-b-d, pp. 7–8 (accessed 4 January 2022).

- 54.

Deloitte, Millennial Innovation survey, January 2013 available at https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/dttl-millennial-innovation-survey.pdf, p. 9 (accessed 4 January 2022).

- 55.

Accenture, Havas Media RE:PURPOSE, The Consumer Study: From Marketing to Mattering, The UN Global Compact-Accenture CEO Study on Sustainability, cit., pp. 9–10; The 2010 Cone Cause Evolution Study, cit., p. 5.

- 56.

- 57.

E.g., see the growth of the US Responsible and Impact Investing movement, which has expanded to encompass about 33% of U.S. investments, roughly $17.1 trillion, as highlighted by the US SIF Foundation’s 2020 Report on US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends, Executive Summary, available at https://www.ussif.org/files/Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf (accessed 4 January 2022).

- 58.

See The 2010 Cone Cause Evolution Study, cit., pp. 19–21; Net Impact’s Talent Report:What Workerswant in 2012 available at https://www.netimpact.org/research-and-publications/talent-report-what-workers-want-in-2012 (accessed 4 January 2022); Clemente (2013), p. 17; Montgomery and Ramus (2007).

- 59.

On the recent debate on corporate purpose, see e.g., Mayer (2013); Mayer (2017), pp. 157–175; Mayer (2018); The British Academy, The Future of the Corporation: Principles for Purposeful Business (Nov. 2019), available at https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/publications/future-of-the-corporation-principles-for-purposeful-business (accessed 4 January 2022); Bebchuk and Tallarita (2020), pp. 91–178; Rock (2020); Lund and Pollman (2021).

- 60.

See https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2018/01/17/a-sense-of-purpose/ (accessed 4 January 2022).

- 61.

See the Business Roundtable statement available at https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans (accessed 4 January 2022).

- 62.

With regard to the entity purpose, hybrid entities’ statutes generally provide for a dual-purpose clause combining profit-making and pursuit of the public benefit, but they do not clearly indicate how these different interests should be prioritised, giving directors a large degree of flexibility. Furthermore, most of the legislations do not address dissenters’ rights for shareholders who oppose the transition to or from the hybrid status but usually require a special majority vote in case of fundamental changes to the entity purpose clause, such as for the introduction or deletion of the social mission.

- 63.

As for directors, they are required to consider or to balance the impact of their decisions not only on the company and the shareholders, but also on other stakeholders (like workers, customers, communities, suppliers and the environment) and the pursuit of the public benefit/s indicated in the company agreement. Thus, directors have great discretion in achieving a higher purpose than simply maximising shareholder value. Moreover, they are generally protected from claims of external stakeholders that generally have no standing to sue both the company and its directors for failing to pursue the company’s social mission. Only shareholders have standing to bring derivative suits alleging breach of fiduciary duties or violations of the duty to pursue the public benefit.

- 64.

For greater accountability and transparency, most statutes require hybrid companies to publicly report about their social and environmental performance using a third-party standard, so customers, workers, investors, and policymakers can assess the company impact.

- 65.

On the different theories on the nature of the corporations, such as the concession theory, aggregate theory, or real entity theory see e.g., Millon (1990), pp. 201–262; Padfield (2014), pp. 327–361; Padfield (2015), pp. 1–34. For a deeper analysis of the famous debate on the issue in the 30s, see Berle (1931), pp. 1049 et seq.; Dodd (1932), pp. 1145 et seq.; Berle (1932), pp. 1365 et seq. On the evolution of Berle’s thought Berle (1954), p. 169; Berle (1959), pp. ix, e xii. For more recent contributions on the issue, see Sommer Jr (1991), pp. 33 et seq.; Harwell Wells (2002), pp. 77 et seq.; Bratton and Wachter (2008), pp. 99 et seq.

- 66.

See e.g., the Green Paper “Promoting a European framework for Corporate Social Responsibility”, 18.7.2001, COM(2001) 366; the Commission Communication of 15 May 2001 on “A Sustainable Europe for a Better World: A European Union Strategy for Sustainable Development”, COM(2001) 264; the Commission Communication of 13 December 2005 “On the review of the Sustainable Development Strategy – A platform for action”, COM(2005) 658; the Commission Communication of 25 October 2011 on “A renewed EU strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility”, COM(2011) 681.

- 67.

Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (“the Non-Financial Reporting Directive”).

- 68.

Directive (EU) 2017/828 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 amending Directive 2007/36/EC as regards the encouragement of long-term shareholder engagement.

- 69.

Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector.

- 70.

Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (the “EU Taxonomy Regulation”). See also the Commission Communication of 21 April 2021 on “EU Taxonomy, Corporate Sustainability Reporting, Sustainability Preferences and Fiduciary Duties: Directing finance towards the European Green Deal”, COM(2021) 188.

- 71.

See the Proposal for a Directive amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as regards corporate sustainability reporting, of 21 April 2021, COM(2021) 189, 2021/0104 (COD), reviewing the Non-Financial Reporting Directive.

- 72.

See the Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain: Final Report (2020), published on 20 February 2020, available at https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8ba0a8fd-4c83-11ea-b8b7-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed 4 January 2022); and the European Parliament resolution (P9_TA(2021)0073) of 10 March 2021 with recommendations to the Commission on corporate due diligence and corporate accountability (2020/2129(INL)).

- 73.

See the Study on Directors’ Duties and Sustainable Corporate Governance: Final Report (2020), published on 29 July 2020, available at https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e47928a2-d20b-11ea-adf7-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed 4 January 2022). For a critique of that study, see Roe et al. (2020).

References

Alcalde Silva J (2018) Observaciones A Un Nuevo Proyecto De Ley Que Regula Las Empresas De Beneficio E Interés Colectivo Desde La Experiencia Comparada. Revista Chilena de Derecho Privado 31:381–425

Alpa G (2016) Il futuro di Law & Economics: le proposte di Guido Calabresi. Contr. e impr. 32:597–607

Bebchuk LA, Tallarita R (2020) The illusory promise of stakeholder governance. Cornell Law Rev 106:91–178

Berle AA (1931) Corporate powers as powers in trust. Harv Law Rev 44:1049–1074

Berle AA (1932) For whom corporate managers are trustees: a note. Harv Law Rev 45:1365–1372

Berle AA (1954) The 20th century capitalist revolution. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

Berle AA (1959) Forward. In: Mason ES (ed) The corporation in modern society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Brakman Reiser D (2010) Blended enterprise and the dual mission dilemma. Vt Law Rev 35:105–116

Bratton WW, Wachter ML (2008) Shareholder primacy’s corporatist origins: Adolf Berle and the modern corporation. J Corp Law 34:99–152

Calabresi G (2016) The future of law & economics. Essay in reform and recollection. Yale University Press, New Heaven, Cambridge, Mass.-London

Clemente M (2013) Benefit corporations: novelty, niche, or revolution. March 7, 2013. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2359226

Cummings B (2012) Benefit corporations: how to enforce a mandate to promote the public interest. Colum Law Rev 122:578–627

Defourny J, Nyssens M (2008) Social enterprise in Europe: recent trends and developments. Soc Enterp J 4:202–228

Dodd EM (1932) For whom are corporate managers trustees? Harv Law Rev 45:1145–1163

Elkington J (1997) Cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone, Oxford

Esposito RT (2013) The social enterprise revolution in corporate law. Wm & Mary Bus Law Rev 4:639–714

Fehr E, Fischbacher U (2003) The nature of human altruism. Nature 425:785–791

Fehr E, Gächter S (2000a) Fairness and retaliation: the economics of reciprocity. J Econ Perspect 14:59–181

Fehr E, Gächter S (2000b) Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev 90:980–994

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (2006) The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism. Experimental evidence and new theories. In: Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 615–691

Fishman JJ (2007) Wrong way Corrigan and recent developments in the nonprofit landscape: a need for new legal approaches. Fordham Law Rev 76:567–607

Fisk P (2010) People planet profit: how to embrace sustainability for innovation and business growth. Kogan Page Ltd, London – Philadelphia

Friedman M (1953) Essays in positive economics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Friedman M (1970) The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970

Gintis H, Bowles S, Boyd R, Fehr E (2003) Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evol Hum Behav 24:153–172

Grant JK (2012) When making money and making a sustainable and societal difference collide: will benefit corporations succeed or fail? Ind Law Rev 46:581–602

Hansmann H, Kraakman R (2001) The end of history for corporate law. Geo Law J 89:439–468

Hargreaves Heap S et al (1995) Game theory. A critical introduction. Routledge, London

Harwell Wells CA (2002) The cycles of corporate social responsibility: an historical retrospective for the twenty-first century. Univ Kan Law Rev 51:77–140

Jackson KT (2010) Global corporate governance: soft law and reputational accountability. Brook J Int Law 35:41–106

Jensen MC (2001) Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. J Appl Corp Finance 22:32–42

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking: fast and slow. Penguin, London

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1974) Judgement under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science New Series 185:1124–1131

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1984) Choice, values, and frames. Am Psychol 39:341–350

Katz RA, Page A (2010) The role of social enterprise. Vt Law Rev 35:59–103

Kelley T (2009) Law and choice of entity on the social enterprise frontier. Tul Law Rev 84:337–377

Kerlin JA (2006) Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 17:247–263

Kerr JE (2008) The creative capitalism spectrum: evaluating corporate social responsibility through a legal lens. Temp Law Rev 81:831–870

Korobkin RB, Ulen TS (2000) Law and behavioral science: removing the rationality assumption from law and economics. Cal Law Rev 88:1051–1144

Lang R, Carrott Minnigh E (2010) The L3C, history, basic construct, and legal framework. Vt Law Rev 35:15–30

Light PC (2008) The search for social entrepreneurship. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC

Lloyd S (2010) Transcript: creating the CIC. Vt Law Rev 35:31–43

Lund DS, Pollman E (2021) The Corporate Governance Machine. European Corporate Governance Institute, Law Working Paper N° 564/2021, February 2021. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3775846

Mayer C (2013) Firm commitment. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Mayer C (2017) Who’s responsible for irresponsible business? An assessment. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 33:157–175

Mayer C (2018) Prosperity. Better business makes the greater good. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Millon D (1990) Theories of the corporation. Duke Law J 1990:201–262

Monoriti A, Ventura L (2017) La società benefit: la nuova dimensione dell’impresa italiana. La Rivista Nel diritto 7:1125–1128

Montgomery DB, Ramus CA (2007) Including corporate social responsibility, environmental sustainability, and ethics in calibrating MBA job preferences. Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 1981. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1077439

Murray JH (2014) Social enterprise innovation: Delaware’s public benefit corporation law. Harv Bus Law Rev 4:345–371

Murray JH (2016) The social enterprise law market. Md Law Rev 75:541–589

Padfield SJ (2014) Rehabilitating concession theory. Okla Law Rev 66:327–361

Padfield SJ (2015) Corporate social responsibility & concession theory. Wm & Mary Bus Law Rev 6:1–34

Parisi F, Smith VL (2005) The law and economics of irrational behavior. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Peter H, Jacquemet MG (2015) Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainable Development et Corporate Governance: quelles corrélations? Revue suisse de droit des affaires et du marché financier 3:170–188

Plerhoples AE (2012) Can an old dog learn new tricks? Applying traditional corporate law principles to social enterprise legislation. Transactions: Tenn J Bus Law 13:221–165

Posner RA (1998) Economic analysis of law, 5th edn. Aspen Law & Business, New York

Reints R (2019) Consumers say they want more sustainable products. Now they have the receipts to prove. In: Fortune, November 5, 2019. https://fortune.com/2019/11/05/sustainability-marketing-consumer-spending/?utm_source=email&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_campaign=business-by-design&utm_content=2019110520pm

Resta G (2014) Gratuità e solidarietà: fondamenti emotivi e ‘irrazionali’. In: Rojas Elgueta G, Vardi N (eds) Oltre il soggetto razionale. Fallimenti cognitivi e razionalità limitata nel diritto privato. Roma Tre Press, Rome, pp 121–161

Rock EB (2020) For whom is the corporation managed in 2020?: The debate over corporate purpose. European Corporate Governance Institute, Law Working Paper N° 515/2020, September 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3589951

Roe MJ et al. (2020) The European Commission’s Sustainable Corporate Governance Report: a critique. European Corporate Governance Institute, Law Working Paper 553/2020, Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 20-30, October 14, 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3711652

Shavell S (2004) Foundations of economics analysis of law. Harvard University Press

Simon HA (1955) A behavioral model of rational choice. Q J Econ 69:99–118

Simon HA (1957) Models of man: social and rational. Wiley, New York

Slaper TF, Hall TJ (2011) Triple bottom line: what is it and how does it work? Indiana Bus Rev 86:4–8

Solomon RC (1998) The moral psychology of business: care and compassion in the corporation. Bus Ethics Q 8:515–533

Sommer AA Jr (1991) Who should the corporation serve? The Berle-Dodd Debate Revisited sixty years later. Del J Corp Law 16:33–56

Stout LA (2014) Law and prosocial behavior. In: The Oxford handbook of behavioral economics and the law. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sunstein CR (1997) Behavioral analysis of law. Univ Chic Law Rev 64:1175–1195

Sunstein CR (2000) Behavioral law and economics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sunstein CR, Jolls C, Thaler RH (1998) A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stan Law Rev 50:1471–1550

Thaler RH (1996) Doing economics without Homo Economicus. In: Medema SG, Samuels WJ (eds) Foundations of research in economics: how do economists do economics?, Elgar, Cheltenham, UK – Northampton (Massachusetts, USA), pp 227–237

Thaler RH, Sunstein CR (2008) Nudge – improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press, New Haven

Toffoletto A (2015) Note minime a margine di Laudato si’. Società 11:1203–1209

Ulen TS (2000) Rational choice theory in law and economics. In: Bockaert B, De Geest G (eds) Encyclopedia of law and economics, pp 790–818

Ventura L (2018) “If not for profit, for what?” Dall’altruismo come ‘bene in sé alla tutela degli stakeholder nelle società lucrative. Rivista del diritto commerciale e del diritto generale delle obbligazioni 3:545–590

Whelan T, Kronthal-Sacco R (2019) Research: actually, consumers do buy sustainable products. In: Harvard Business Review, 19 June 2019. https://hbr.org/2019/06/research-actually-consumers-do-buy-sustainable-products

Yockey JW (2015) Does social enterprise law matter? Ala Law Rev 66:767–824

Zamir E, Teichman D (2014) The Oxford handbook of behavioral economics and the law. Oxford University Press, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ventura, L. (2023). The Social Enterprise Movement and the Birth of Hybrid Organisational Forms as Policy Response to the Growing Demand for Firm Altruism. In: Peter, H., Vargas Vasserot, C., Alcalde Silva, J. (eds) The International Handbook of Social Enterprise Law . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14216-1_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14216-1_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14215-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14216-1

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)