Abstract

The values driving entrepreneurs are evolving from shareholder wealth maximization towards a more holistic approach wherein business impacts on all stakeholders are considered. This change has been driven in part by a societal cultural shift focused on promoting a sustainable future. To meet this cultural change demanding a balance of profit and ethics, novel entities (e.g., B Corps) have emerged in the private sector. In this chapter, we engage with behavioral perspectives to explore B Corps’ achievements, opportunities, and challenges. We first outline the transition from shareholder to stakeholder considerations, as we believe it constitutes the philosophical ethos of social enterprises. We then focus in turn on four of the five areas used by B Lab’s Impact Assessment—governance, workers, customers and consumers, and community—as they are most appropriate for an exploratory analysis of their interaction with human behavior. Specifically, in governance, we approach the topic of corporate ethics and transparency, as well as how the values of social entrepreneurs shape a firm’s culture. We then outline the relationship between purposeful work and employee performance and examine how B Corps have applied effective practices on social inclusion and employee well-being, in the workers’ section. Concerning customers and consumers, we explore a range of perspectives, including consumer motivations to purchase from B Corps, caveats of ethical consumerism, and how B Corps can capitalize on decision-making research to inspire consumer change. Additionally, we present our research on public awareness and perceptions of B Corp trustworthiness and greenwashing. Finally, the last section—community—highlights B Corps’ civic engagement and communication with their communities through social media, corporate volunteering, and charity work, among others.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Context

The Friedman doctrineFootnote 1 asserts that a company’s primary responsibility is to maximize shareholder wealth. For decades, it has been the core of the most influential ideas behind modern Western economics, shaping the private sector, particularly in the US. Leveraged at a time of uncertainty, it quickly gained corporate and political traction and became the dominant business mindset until recently. The doctrine prevailed over competing contemporary proposals, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) advocated by Bowen, who stated that businessmen’s obligations are to pursue policies and make decisions that are desirable and of value to society.Footnote 2 Friedman’s doctrinal influence embedded itself into corporate cultures and emerging management styles, and concerns related to consumers, workers, and the environment remained secondary or even neglected as managers focused on profit maximization.

HestadFootnote 3 highlights that this still-widespread managerial culture—in which workers are conceptualized as economic agents, placed in a competitive environment, and incentivized to become increasingly productive, efficient, and profitable—generates false dichotomies. Specifically, dichotomies between present and future (i.e., maximizing profit each quarter while often disregarding long-term negative consequences), management and employees (i.e., establishing and maintaining a top-down culture of control and hierarchy), and lastly economy and nature (i.e., prioritizing financial growth at the expense of preserving the environment, frequently without adequate damage management and prevention). Recent studies highlight how these tensions are not actual intrinsic properties of business activities but rather mistaken human conceptualizations, as there are no real boundaries between organizations and the socio-ecological systems in which they are embedded.Footnote 4 Transcending such artificially defined boundaries entails a shift in the cultural and value systems of enterprises and the development of integrated perspectives on business, society, and the environment, which considers their effects from a systemic perspective and goes beyond profit motives. In a limited-resource system bound by natural laws, pursuing perpetual growth in a framework of false dichotomies is not only unsustainable but actively damaging to human health and well-being, as well as to biodiversity and ecosystems.

As a concrete example of the ineffectiveness of previous paradigms, pitting employees against each other in a quest to increase competition and efficiency resulted in the near-complete dissolution of Sears.Footnote 5,Footnote 6 Expecting that pure competition would stimulate highly rational decision-making and lead to the most profitable and efficient outcomes, Sears CEO Eddie Lampert divided the company into 30 units; however, this action backfired when unit executives attempted to undermine each other to boost their performance-dependent bonuses. As everyone became focused on self-interest and competition with other units, the importance of cooperation was forgotten, which actively led to overall brand damage.Footnote 7 This case adds to unequivocal evidence from the behavioral sciences demonstrating that humans do not behave like rational economic agents, but rather frequently follow predictable heuristics (also known as biases) resulting from cognitive and affective decision mechanisms rooted in evolutionary adaptations.Footnote 8,Footnote 9 Not only is the assumption of rationality unsuitable, but additional evidence from social neuroscience emphasizes that the brain’s intrinsic social wiring drives humans to cooperate and bond.Footnote 10,Footnote 11 Thus, an environment dominated by overcompetition and disregard for human instincts is more likely to result in reduced efficiency and trust as well as increased unethical behavior. This combination has negative implications for well-being and team performance and ultimately for firm profitability. For instance, on well-being, reports have shown an increased prevalence of mental health conditions related to work stress (such as anxiety and burnout): 44% of employees in 2018 reported work had caused or aggravated a mental health condition, representing a 10% increase from 2008 and an annual cost of £42–£45 billion to the UK economy.Footnote 12 Ripple effects have also been observed at other levels of society, prominently widespread public distrust resulting from high corporate executive pay, managerial corruption, and unsuitable treatment of the workforce.Footnote 13 Taken together, these findings portray various shortcomings of a shareholder wealth-maximizing economy. In parallel to the realization of these shortcomings, past years have seen a growing societal sentiment that both individuals and the private sector should not focus solely on profit maximization but also on ensuring a sustainable future. For instance, in 2016, only 19% of Americans aged 18–29 identified as capitalists according to a Harvard Institute of Politics study, a drop from 49% in 2010.Footnote 14,Footnote 15,Footnote 16 Furthermore, mainstream media have increasingly raised awareness on the current climate and biodiversity crisis.Footnote 17,Footnote 18

Thus, at the turn of the millennium, scholarsFootnote 19 and business leaders began questioning the validity—and more importantly the sustainability—of the notions of value, wealth, and efficiency. This reevaluation, along with a growing frustration with the “growth at all costs” mindset, has led to the reconsideration of alternative business doctrines, such as that proposed by Bowen.Footnote 20 It comes in the form of new frameworks for assessing performance, such as the triple bottom line (profit, people, planet),Footnote 21 environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investment criteria,Footnote 22 and hybrid companies or social enterprises,Footnote 23 such as B CorpsFootnote 24 and benefit corporations,Footnote 25 all underlain by one common principle: purpose-driven strategy. Both the frameworks and company certifications revolve around a similar core concept, that of moving away from shareholder capitalism and toward stake holder capitalism, in which other agents participating in or affected by the system are considered. These companies differ from traditional philanthropic or other nonprofit organizations as they still aim to generate a profit, and they are also distinct from traditional companies as they seek to create social and ecological value (e.g., sustainable resource use, worker well-being, protection of biodiversity) alongside financial returns (see Fig. 1 for a visual representation). It is worth noting that traditional companies have long incorporated purpose-driven practices under the most widely known form of CSR. CSR practices, however, are typically unverifiable, and while some companies have adopted them genuinely, inauthentic CSR used for advancing profit-maximization motives in disguise has faced repeated media coverage and public backlash. This phenomenon, often labeled “greenwashing,” has eroded public trust in CSR claims.Footnote 26 Thus, there is a need to differentiate honest social enterprises from greenwashers and create standards for firms aspiring to be considered social enterprises.

The spectrum of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and traditional for-profit organizations (Adapted from Alter (2007))

In this spirit, the California-based nonprofit organization B Lab launched B Corp certification in 2007. Since then, more than 4500 companies have been certified in over 75 countries and across 150 industries.Footnote 27 Notable global brands that have become certified include Patagonia, Danone, Ben & Jerry’s, and Seventh Generation. B Corps’ hybrid approach entails the pairing of economic motives with a social or environmental purpose and holistically considering all stakeholders and aspects that may be impacted by the company. B Lab evaluates potential applicants through the B Impact Assessment, which comprises five areas of evaluation: governance, workers, customers, community, and environment. To become certified, a company must obtain a minimum of 80 points out of 200. Governance primarily addresses ethics, mission, and transparency; workers evaluates aspects such as financial security, health and wellness, engagement, satisfaction, and employee career development; customers considers stewardship and whether the product or service provides a solution to a socio-ecological problem; community is concerned with diversity and inclusion, supply-chain ethics, engagement with local communities, and charity; and lastly environment focuses on sustainable practices, such as recycled materials and renewable energy, alongside waste reduction and wildlife conservation.Footnote 28 B Corps are also subject to random on-site audits by B Lab, meant to enhance company accountability. Overall, the B Corp certificate is not just another label attached to a product, instead it represents a bottom-up effort to shift the status quo of corporate misbehavior to re-establish public trustFootnote 29 while creating a novel economic sector.Footnote 30 Interestingly, there are more emerging B Corps in industries that exhibit strong hostile shareholder-centric tendencies (e.g., mass layoffs, excessive income inequality between executives and employees) than in less hostile environments,Footnote 31 further supporting the movement’s driving ethos to counteract the negative consequences of a pure profit motive.

Much of the B Corps literature, reviewed by Diez-Busto and colleagues in 2021,Footnote 32 focuses on conceptual analysis or review,Footnote 33 legal discussions,Footnote 34 financial or growth-oriented aspects,Footnote 35 and evaluating sustainability achievements.Footnote 36 There is, however, little scholarly work analyzing the benefits and challenges of B Corps from a behavioral perspective, as it is a rather young field. The few existing studies examine employee productivity,Footnote 37 entrepreneur and firm motivations,Footnote 38 and consumer motivations to purchase from B Corps.Footnote 39 Crucially, B Corps success is driven in part by placing humans and their values at the center of their entrepreneurial project. Given those behavioral sciences are intrinsically focused on understanding human behavior, they represent the foundation for analyzing how B Corps can, likely positively, influence workers, consumers, communities, or what factors determine successful policies. Therefore, to provide an informed overview of the behavioral aspects, we engage with interdisciplinary literature across the behavioral sciences, as well as sustainability investigations, consultancy research, and case studies. Together, these illustrate the ways in which B Corps positively contribute to society and how they can make use of insights from behavioral sciences to leverage their certification.

Considering the five aforementioned areas of the B Impact Assessment, the remainder of this chapter explores the first four categories, as these represent aspects wherein human behavioral phenomena are most evident. Section 2 evaluates governance, specifically the influence of ethics, transparency, and accountability on the internal and external relationships of B Corps, as well as the implications of managerial style on interpersonal relationships and work culture. Section 3, workers, explores the relationship between working with purpose and employee performance and the effects of social inclusion on employees’ health, presenting some examples of B Corps with leading practices in this regard. Next, Sect. 4 on customers (which we extend to consumers more generally) covers the synergy between consumer motivations and B Corp activity, caveats of moral behavior, and techniques to influence more sustainable consumer behavior; we also present our research regarding public awareness and perceptions of B Corp trust and greenwashing. Lastly, Sect. 5, community, discusses some of the ways in which B Corps engage with their communities through social media, corporate volunteering, and charity work, among others.

2 Governance

Governance represents the set of governing principles a company bases its activity on. While not a direct behavioral measure, it can greatly influence the behavioral dynamics within a company via corporate culture and subsequent team dynamics. The B Impact Assessment evaluates, among other aspects, governance ethics, accountability, and transparency, which are of particular relevance to behavioral outcomes.

2.1 Ethics, Transparency, and Trust

Ethics refers to the set of moral principles guiding integrity and honest behavior. In examining the relationship between implementing an ethics code, corporate philanthropy, and employee engagement and turnover in the hospitality sector, Lee and colleaguesFootnote 40 found that awareness of a code of ethics positively contributed to corporate philanthropy and organizational engagement. Further, they found an effect of corporate philanthropy on job and organizational engagement, both of which were negatively correlated with turnover. Overall, a code of ethics and a culture of corporate philanthropy increase employee moraleFootnote 41 and commitment.Footnote 42 Conversely, employees in work climates lacking a code of ethics experienced greater conflicts and increased turnover.Footnote 43 B Corps who excel in governance, particularly if they implement an internal code of ethics, would likely see similar benefits.

Accountability represents the obligation of being able to justify one’s actions to those who may be affected by themFootnote 44 and can extend to requiring rectifying one’s behavior in case of misaction. Similarly, transparency concerns reducing information asymmetry between managers and stakeholders,Footnote 45 which, in the business context, refers to openly communicating operating practices and reparatory actions with concerned stakeholders. Emerging literature suggests that B Corp certification can positively impact accountability and transparency, increasing the quality of corporate governance.Footnote 46 Across industries (e.g., hospitality,Footnote 47 telecom,Footnote 48 and financeFootnote 49), transparency has been consistently associated with higher stakeholder trust. In turn, higher trust is associated with higher predictability, representing a met expectation of the other party’s good will,Footnote 50 both of which lay the foundation for mutuality of intention and enhanced cooperation. The importance of transparency in building trust is no longer a novel concept—in PwC’s annual CEO survey,Footnote 51 the percentage of CEOs who considered transparency critical for trust-based relationships in business increased from 37% in 2013 to 60% in 2018, indicating a shift in values at the highest corporate levels. Interestingly, the percentage decreased to 50% in 2019, suggesting a shift from simple concern to proactive action, as leaders started implementing trust-building strategies based on transparency to meet stakeholder expectations.Footnote 52 When trust is eroded, accountability can be a means of restoring it; however, displays of accountability should not be used solely as instruments to repair a company’s self-image. Similarly with how strategic CSR negatively impacts trust when it is used for self-interested motives, tactical accountability is detrimental to an organization’s trustworthiness. Footnote 53 When examining how B Corps integrate these principles with their operations, future research should assess whether B Corps and benefit corporations are indeed more transparent and accountable than matched peers and the subsequent implications for mutual relationships with stakeholders, as well as public perceptions of trustworthiness.

2.2 Implications of Entrepreneurs’ Value Structures

Beyond the aspects evaluated by the B Impact Assessment, we posit that several other facets remain relevant when exploring governance’s influence on behavior. As previously mentioned, governance plays a role in defining a company’s culture, particularly via their leaders’ personality and behavioral tendencies. It follows that the particular personality types of both founders and managers will further influence team dynamics. Good governance would thus consider the influence of leaders’ personality types on organizational functioning, specifically considering interpersonal relationships.

Concerning entrepreneurs, Roth and WinklerFootnote 54 created a taxonomy of profiles by investigating personal motivations and values of B Corps entrepreneurs in Chile and categorizing them based on their social, environmental, and profit motivations. Four profiles emerged: (1) the social idealist, (2) the sustainable impact seeker, (3) the hybrid achiever, and (4) the self-sustaining hedonist. The first is characterized by defining success based on generated social value and a strong motivation to include both in-group and out-group members in the process.Footnote 55 Social idealists always prioritize social impact over financial gain and use profit only as a tool to support the continued activity of the B Corp. They are distinguished by their strong sense of community belonging and a desire for deeply connected relationships with others. Sustainable impact seekers define success as a combination of financial and social value generation metrics but continuing to show a strong motivation for welfare creation for everyone.Footnote 56 They value close, harmonious work relationships and include employee well-being as an indicator of success, which is measured by both financial and social impact indicators. Hybrid achievers also define personal achievement in a mixed manner similar to the second profile; however, the hybrid achiever’s definition of success is more closely aligned to profit metrics when compared to the first two. Moreover, personal achievement is a primary motivator for this kind of B Corp entrepreneur. Nonetheless, they are unwilling to generate profit if negative consequences exist, as they value ethical business practices and transparency. Lastly, self-sustaining hedonists are driven by their profit-oriented definition of success and have no particular expressed motivation for social value creation for in-group or out-group members. Pursuing personal passions is their primary motivator. This type was the least common among the sample.

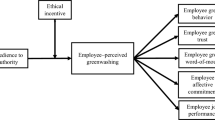

Studies have suggested that, generally, the motivation underpinning value creation reflects internal value structuresFootnote 57 and that social entrepreneurs are more likely to be motivated by inherent personal values regarding a social or environmental cause.Footnote 58 It follows that internal value structures will influence work priorities and organizational culture. With the increasing use of greenwashing because of its potential as an avenue for higher profits, we argue the self-sustaining hedonist is more likely to diverge from the fundamental purpose of creating a B Corp than the other profiles and thus would pursue certification for self-gratifying motives. B Corps led by this type of leader could potentially threaten the credibility and trustworthiness of the B Corp label. Further, a self-interested leader is more likely to neglect the social harmony necessary for effective teamwork, which may be more important for B Corps than for standard companies given the former’s focus on mutual value creation and stakeholder engagement. While no particular research has been conducted on the influence of the aforementioned profile types on B Corp culture, insights from social and organizational psychology support the idea that prosocial behaviors elicit positive outcomes such as creativity and innovation in organizational settings.Footnote 59 For example, ethical leadership (characterized by honesty, altruism, and trustworthiness) has been associated with positive organizational citizenship behavior,Footnote 60 employee creativity,Footnote 61 and job performance.Footnote 62 It also encourages employee participation and fosters an environment of openness and collaboration.Footnote 63 These effects can be explained using social exchange theory,Footnote 64 which posits that if the cost–benefit evaluation of a social interaction is positive (i.e., rewards are higher than costs), the interaction will be mutually beneficial. In the case of organizations, subordinates who perceive a strong positive exchange with their leaders will experience feelings of gratitude and trust, which elicit motivation to return the favor through their work behaviors. Footnote 65 Unsurprisingly, B Corps in Latin America that exhibit strong managerial support have higher rates of innovative work behavior.Footnote 66 Conversely, leaders exhibiting a lack of empathy or concern for others (e.g., as seen in subclinical psychopathy or narcissism), often induce psychological distress and distrust in their subordinates and generate unhealthy interpersonal relationships, which affects job performance and even individual health.Footnote 67

Taken together, we argue that, given their heightened prosocial tendencies, the first three profiles described above are more compatible with the B Corp philosophy as opposed to the self-sustaining hedonist. To avoid abuse of its label and increase the likelihood that B Corps reflect the movement’s values, B Lab could include evaluating the individual value structure and motivations of B Corp certification-seekers in the B Impact Assessment. Future research should investigate the prevalence of leaders’ prosocial tendencies among certified B Corporations and matched non-B Corp companies to identify whether differences exist. Other studies should attempt to identify the causal relationship between varied motivational profiles and their corresponding effects on organizational culture and stakeholder relationships in B Corps vs. standard firms.

In summary, governance encompasses several factors that have behavioral implications. First, the implementation of a code of ethics promotes internal coherence, employee morale, and reduced risk of conflict. Second, transparency facilitates stakeholder trust, and accountability can serve as a means of repairing trust in case of misaction. Lastly, because the intrinsic value structures and personality profile of B Corp leaders likely shape the development of B Corps, their internal functioning, and their credibility over time, B Lab could consider implementing a profile evaluation of B Corp certification-seekers to ensure compatibility between B Lab’s goals and the philosophies of emerging B Corp entrepreneurs.

3 Workers

3.1 Working with Purpose, CSR, and Employee Performance

Time at work comprises nearly a third of a person’s life, so making work meaningful through purpose is an increasing priority for many. In a survey by McKinsey,Footnote 68 70% reported that work is important for their sense of purpose, yet 49% of frontline workers disagreed that their purpose is fulfilled at work, with a further 36% being unsure. Interestingly, this response contrasts with that of top executives, among whom 85% reported that their sense of purpose aligns with work. Employees who feel more aligned with their work purpose are more likely to report higher levels of energy, resilience, and commitment, in addition to improved physical health, a claim supported by medical research.Footnote 69 PwC’s researchFootnote 70 highlights another intriguing gap between employees and executives (see Fig. 2): employees value a sense of purpose for daily meaning, a sense of community, and the energized feeling of genuine impact, while executives prioritize it as means of gaining more distinction and improved reputation. Overall, there is widespread demand for purpose-driven work with 74% of people surveyed believing a successful business needs to have a genuine purpose that resonates with people, and 75% caring to work for a business that matches their values. Footnote 71 Importantly, these trends are even stronger in younger generations: 10% more millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) care about making a positive difference in the world through their careers compared to Gen Xers (born between 1965 and 1980).Footnote 72

There is no doubt that employees have intrinsic motivations that keep them engaged beyond financial compensation and that conducting purposeful business comes with behavioral benefits at the worker level. Extensive research has explored the relationship between CSR and employee job satisfaction, performance, retention, and commitment. Footnote 73 CSR programs and prosocial incentives show positive correlations with satisfaction,Footnote 74 commitment,Footnote 75 and effort and productivity.Footnote 76,Footnote 77 Indeed, such results are consistent with theoretical arguments positing that prosocial incentives would motivate those who have intrinsic prosocial preferences.Footnote 78 This is also supported by real-world data showing that 71% of respondents to an IBM surveyFootnote 79 exhibited prosocial preferences, stating they were more likely to both apply and accept a job from a company demonstrating social responsibility. Other important empirical findings suggest that CSR policies both attract and increase retention of better talent,Footnote 80 thereby lowering turnoverFootnote 81 and increasing engagement.Footnote 82 Indeed, these trends in the more general CSR literature have begun to emerge in the nascent B Corp literature, as well. Romi and colleaguesFootnote 83 found that for B Corps who scored highly (i.e., is an “area of excellence”) on treatment of workers on the B Impact Assessment, employee productivity was significantly higher compared to matched standard companies, and the relationship held true for sales growth, as well. Therefore, a work environment in which ethical concerns are evident and characterized by a broader consideration of its relationship to its surrounding systems is more positively perceived by employees and generates considerable behavioral benefits. However, the intention behind such prosocial policies matters. If they are used instrumentally, that is, as a proxy to achieve profit-centered goals and not for their intrinsic social or environmental value, they tend to backfire and lead to a negative perception of the firm and a loss of the desired behavioral improvements.Footnote 84

Having purpose at work and working in a prosocial and considerate environment are intrinsic to the aims of B Corp certification. The certification can appeal to prospective employees’ sense of purpose and social identity (i.e., positioning themselves in a social environment of shared values), thereby attracting mission-aligned talent. Unsurprisingly, B Corps are the first employer choice for millennials in the US.Footnote 85 Because the B Corp mission and employees’ ideological needs align, not only is job satisfaction increased,Footnote 86 but affective commitment, which refers to an emotional bond to a cause’s values or ideals that elicits the desire to pursue congruent actions,Footnote 87 is enhanced. Bingham and colleaguesFootnote 88 posit that affective commitment is one of the strongest predictors of employees’ behavioral support of an organization’s cause, alongside (although to a lesser extent) normative commitment (employees feeling ethically obligated to support a cause because it is the normatively correct course of action and continuance commitment (employees being aware of the cost of not following the organizational cause).Footnote 89 Further, start-up B Corps or those that cannot match pay rates of standard for-profit businesses can still attract motivated talent, with research showing that employees are willing to accept a lower pay if working for genuinely responsible companies.Footnote 90

Together, the mission and purpose of B Corps have the potential to attract mission-aligned and committed talent with higher motivation and engagement to support a given cause. Additionally, B Corp leaders are more likely to value purpose at work for similar reasons as employees (i.e., day-to-day meaning, sense of community, making an impact) rather than for recognition and status, given their intrinsic social motivations (as described in Sect. 2).

3.2 Social Inclusion and Well-Being at Work

Moving on from work-related benefits to a more people-centric perspective, the interpersonal component of socially aware companies is equally important for generating a healthy and supportive environment. The United Nations (UN) World Happiness ReportFootnote 91 finds that social support explains the highest variance in measured happiness, ahead of GDP per capita, which ranked second. Social support is a powerful buffer against both work stressFootnote 92 and negative affect more generally.Footnote 93 This is relevant both at the individual level, given that higher levels of work stress increase the risk of immune system and cardiovascular disorders and worsen mental health, and at the organizational level, as it decreases performance while increasing absenteeism and turnover.Footnote 94 Another central factor contributing to healthy and supportive work environments is trust, which is a predictor of subjective well-being and social cohesionFootnote 95 and maintains its influence across environments (i.e., both in day-to-day life and at work). Moreover, a 10% increase in trust management corresponds to an increase in life satisfaction equivalent to a 36% increase in income.Footnote 96 Together, social support and trust represent a foundation for social capital, defined as “a combination of interpersonal links, shared beliefs and identities, and norms that together reduce the incidence of distrust in economic exchange and teamwork.”Footnote 97 Considering it as capital is appropriate because, just like financial capital, the weight of social networks accumulates over time and yields benefits such as reinforced trust, mutuality of intention, and efficient cooperation.

Interestingly, Culture Amp, a B Corp concerned with improving corporate cultures, has identified that B Corp employees express more trust regarding company commitment to positive social impact: 82% of employees agreed that their company’s commitment is genuine compared to 70% at non-B Corps.Footnote 98 While not a direct measure of interpersonal trust, this finding does reflect higher trust in management compared to non-B Corps, which has been shown to facilitate team performance.Footnote 99 Moreover, Culture Amp found a 12% difference between B Corp and non-B Corp employees on whether employees felt they could make a genuine impact, and overall, B Corp employees perceived their leadership as more inspiring and motivating.Footnote 100 This is consistent with case studies of B CorpsFootnote 101 that identified that such companies have empathetic leadership, implement democratic governance, and promote a collaborative work environment based on trust and equality.

Another example comes from Forster Communication, a UK-based company featured in B Lab’s Best for The World honorees listFootnote 102 for their worker- and governance-related performance and named one of Britain’s Healthiest Workplaces.Footnote 103 Tackling formerly stigmatized topics such as mental health, this company seeks to create inclusive cultures wherein discussing employees’ emotional and personal needs is not prejudicial or puts their job at risk but rather is encouraged and welcomed.Footnote 104 To contextualize the importance of workplace mental health, DeloitteFootnote 105 estimates that in the UK alone, poor mental health currently cost employers £42–£45 billion a year in 2018, compared to £33–£42 billion in 2017, representing an approximate 16% increase. Despite this considerable impact, it remains a largely taboo topic, with as many as 300,000 people losing or quitting their jobs due to a mental health condition.Footnote 106 Furthermore, BCG’s researchFootnote 107 shows that a lack of perceived social support adversely impacts employees’ work and private lives and that overall, employees whose work environments feel inclusive are 3.3 times more likely to feel supported by their managers and 2.6 times more likely to feel safe making a mistake (see Fig. 3). These results are complemented by insights from social neuroscience that show that social rejection activates similar brain networks to physical pain,Footnote 108 impairs high-order cognitive abilities such as problem-solving,Footnote 109 and increases risk of stress related disorders such as depression and anxiety. Conversely, social support is linked to cognitive resilience,Footnote 110 enhanced global cognition,Footnote 111 and higher likelihood of good physical and mental health.Footnote 112

Percentage of people who agree with the specific statements, by company type (Adapted from: BCG (2021) Inclusive Cultures Have Healthier and Happier Workers. Available at: https://www.bcg.com/en-ch/publications/2021/building-an-inclusive-culture-leads-to-happier-healthier-workers)

In this context, Forster Communications’ advocacy for destigmatization of mental health and wider social inclusion is not simply about following B Lab’s health and well-being guidelines but is the scientifically sound course of action. It also sets an industry example for approaching mental health and inclusion and encourages other companies to follow suit. The company further proves its comprehensive understanding of the multifactorial determinants of health and well-being by, for instance, advocating for physical activity and balanced nutrition. Specifically, it incentivizes employees to bike to work Footnote 113, Footnote 114 by offering equivalent time off from “pedal points,” a policy that both lowers individual carbon footprints and improves personal physical health, further promoted by free on-site healthy breakfast options. Unsurprisingly, their health-related absenteeism and presenteeism is 15–30%Footnote 115,Footnote 116 lower than the UK average.

Other B Corps also show consideration for their workers’ health as well as carbon footprints. US-based Dr. Bronner’s offers free vegan and vegetarian food and subsidies for electric vehicles to its employees. Dr. Bronner’s is particularly committed to B Lab’s vision, having been included on B Lab’s Best for the World honoree list several times and attaining a B Score of 178 out of 200.Footnote 117 The company’s most striking stance is its position on wage inequality; it limited top management’s earnings at five times that of an entry level employeeFootnote 118 (compared to a US average of 351-to-1 in 2020Footnote 119) and offers a minimum wage of almost US$19 per hour,Footnote 120 160% higher than California’s US$11 per hour in 2018.Footnote 121, Footnote 122

In summary, now that purposeful work is more important than ever, B Corps’ holistic value creation missions appeal to mission-aligned talent, which leads to increased retention, engagement, satisfaction, and performance. Emerging evidence demonstrates the movement’s commitment to offering not just career opportunities and development but also its concern for workers’ health and well-being through inclusion and social acceptance. In addition, B Corps consider fair wage distribution and employee financial security. Overall, B Corps are 55% more likely to cover at least partial health insurance costs and 45% more likely to offer bonuses regardless of employees’ company rank, and 54% have reported their intention to share profits with employees.Footnote 123 Lastly, they acknowledge their influence on employees beyond arguably self-interested measures (e.g., employee performance), seeking to incentivize workers to become more responsible citizens through sustainable behaviors.

3.3 Future Research

In our literature review, we identified a lack of systematic studies comparing B Corp environments to those of companies with varying degrees of CSR commitments and of standard for-profit organizations as a baseline. Behavioral data specific to B Corps is sparse, and while the CSR literature is partially applicable, it is important to identify specific B Corp-related effects on employee behavior. The B Corp environment offers ample opportunity for research, particularly because a standardized framework of assessment is available, contrary to the CSR literature, which lacks rigorous and consistent definitions of CSR meaning and policies. Indeed, B Corps also differ in terms of individual area scores; however, certified companies with similar scores in one category will certainly be more comparable given the homogeneity of evaluation criteria. Future research can consider comparing B Corps and traditional companies on employee trust in management, self-reported fulfillment, mental health measures, and productivity and engagement. Findings would serve as a foundation for identifying what specific B Corp characteristics are most effective in driving a particularly desired behavioral outcome and which could inform future corporate policies aiming to tackle current challenges in the work environment.

4 Customers and Consumers

This section considers the relationship between B Corps and customers and consumers,Footnote 124 focusing on six components: (1) the consumer landscape and the general demands of current consumers; (2) consumer motivations to purchase from B Corps; (3) moral licensing and the caveats of ethical consumerism B Corps should consider; (4) inspiring consumer change, which highlights some behavioral insights B Corps can leverage to incentivize a shift in consumption patterns; (5) exploring public awareness and perceptions of B Corps; and (6) methodological notes and future research.

4.1 The Consumer Landscape

Consumer preferences are trending toward increased awareness and concern for social ethics and sustainability, following wider exposure through digital media (among other sources) to the need for more sustainable consumption. This trend has been further strengthened by a number of corporate scandals such as oil spills and plastic pollution. Accenture’s 2018 Global Consumer Pulse ResearchFootnote 125 revealed that 62% of consumers “want companies to take a stand on current and broadly relevant issues” (e.g., sustainability, transparency, fair employment practices). IBM’s researchFootnote 126 mirrors this trend, with two out of three global respondents expressing deep concern for environmental issues and three out of four for social issues. This shift in consumer concerns has also been observed in the financial world, with an increased demand for sustainable investments, which resulted in a 96% growth between 2019 and 2020.Footnote 127 More recent data from Accenture’s 2021 Global Consumer Pulse reportFootnote 128 also found that 50% of consumers strongly agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic made them revise their personal purpose and what they deem as important in life (labeled reimagined consumers), while only 17% maintained the same attitudes (labeled traditional consumers). Of reimagined consumers, 70% believed private companies were just as responsible as elected governments for societal health compared to 40% of traditional consumers, a perspective that correlates with their increased emphasis on categories such as health and safety, product origin, and trust and reputation when choosing products or services. In other words, for most individuals, price and quality are no longer the primary drivers of their decision-making. Intriguingly, reimagined consumers seem to have shifted their social attitudes as well, with 42% recognizing the importance of focusing on others and not just themselves, marking a shift toward empathy. Lastly, 57% of reimagined consumers were ready to switch from their current providers to alternative ones more aligned with their views on pandemic, economic, or societal issues. Importantly, 50% actually took action to change, a stark contrast with the so-called intention-action gap finding that captures a discrepancy in consumers behavior (i.e., 65% indicate they care to buy from purpose-driven brands, but only 26% act on their intentionFootnote 129). This suggests the COVID-19 pandemic has been a catalyst for behavior change.Footnote 130

While all factors that became more important to consumers (health and safety, product origin, and trust and reputation) are aspects that B Corps can capitalize on when marketing themselves to consumers, the latter two are particularly relevant. First, product origin encompasses supply-chain ethics, an area where B Corps have potential to excel given that supply-chain ethics is a core determinant of whether a company receives B Corp certification. Delivering ethical products while being transparent about product origins is a major competitive advantage, as 94% of consumers report they are more likely to be loyal to brands that deliver complete transparency.Footnote 131 As discussed in Sect. 2, transparency has implications for trust and reputation; specifically in the context of consumer decision-making, it has been found to promote customer loyalty. For example, the B Corp Ben & Jerry’s found that consumers are 2.5 times more loyal to purpose-driven and trustworthy companies.Footnote 132 Most importantly, trust safeguards against greenwashing skepticism, which is increasing together with conscious consumerism. Greenwashing suspicions are, predictably, inversely correlated with brand trust,Footnote 133 and faced with growing CSR claims across a wide spectrum of companies, consumers have difficulty differentiating between genuine CSR and CSR for self-interested purposes such as financial gain.Footnote 134 Parguel and colleaguesFootnote 135 suggest independently generated sustainability ratings as a possible solution. Thus, B Corps could educate and inform consumers more generally about B Impact Assessment scores and use their scores as performance markers in target marketing areas to differentiate themselves from competitors while ensuring scores genuinely reflect their practices. A limitation of this approach, however, is that in the case of various ratings, most companies could pick and choose to find one that provides “proof” of their positive impact. So, it is crucial for B Corps to clearly communicate their scores in a consistent and structured manner and to emphasize their accountability to B Lab’s assessment and on-site audits. Demonstrating accountability to a consistent third-party evaluator in a standardized manner will most likely increase trust and company reputation among consumers; however, a prerequisite of the success of this process is that consumers are aware of the certification itself and its rigorous standards.

4.2 Consumer Motivations Behind B Corp Purchases

To date, only two studiesFootnote 136 have investigated consumer motivations and intentions to purchase specifically from B Corps; one is qualitative and the other quantitative, and both were carried out in Chile, a growing hub for B Corps.

The first study Footnote 137 relied on semi-structured interviews to identify decision chains that underlie participants’ purchase motivations. An analysis of which attributes of B Corp products or services are most often mentioned found that recyclable, reusable, or recycled products, and the B Corp accreditation itself were the main factors. When prompted on why these were important, participants responded by linking them to impacts such as reduced pollution and waste, helping local communities, and, more interestingly, a strong association between the accreditation label and increased trust, as mentioned in Sect. 4.1. At the very core of participants’ rationales behind the mentioned attributes and impacts, the researchers identified two overarching consumer values: (1) intrinsic socio-environmental responsibility and (2) self-satisfaction. Interestingly, the relationship between positive impacts (e.g., reduced pollution) and the self-satisfaction motive was interlinked by participants’ feeling they are an agent of change (i.e., on reducing pollution, helping others/local communities, or being part of a purposeful movement) and feeling gratified their actions to have an actual positive impact.

These two governing values are consistent with results from behavioral science suggesting that conforming to social norms and a desire to live in accordance with an idealized self are powerful catalysts for behavior change.Footnote 138 Implicitly, if social norms favor heightened environmental responsibility, they will influence individuals’ acceptance of these values as well, thus increasing the likelihood that individuals will develop an internal moral compass guided by sustainable-behavior norms. In turn, as their reference of what constitutes personal moral behavior changes, it precipitates behavior change such that they adhere to their own moral compass, ultimately leading to self-satisfaction. Thus, B Corps can appeal to various consumer values and motivations when promoting themselves. First, they can emphasize the role consumers play as agents of change, thereby eliciting self-satisfaction as well as appealing to their intrinsic socio-environmental responsibility; second, they can emphasize social norms by, for example, outlining the proportion of consumers who engage in ethical consumerism, thus incentivizing individual consumers to follow these social norms.

The second studyFootnote 139 replicates the finding that intrinsic socio-environmental responsibility and increased self-satisfaction are related to consumer intentions to purchase from B Corps. In addition, they also find that perceived behavioral control is significantly correlated with purchase intention. Perceived behavioral control the belief that one is able to execute a particular behavior. Financial resources are often necessary for sustainable consumption and are thus tied to the perceived behavioral control that one can indeed purchase from B Corps. It follows that the perceived behavioral control of consumers intending to purchase from B Corps will be influenced by their financial resources and willingness to pay. On sustainable consumption more generally, surveys have found that between 45%Footnote 140 and 57%Footnote 141 of consumers were willing to pay a premium for sustainable brands or brands matching their values. However, we believe that B Corps, because of their commitment to consumers and communities at large, should also consider lower-income groups and attempt to make their products or services more accessible where possible. Inaccessible B-certified products or services would be demotivating to this demographic, caused by a loss of perceived behavioral control, which would likely result in lower adoption rates. In Sect. 4.5.2, we further present consumer insights on the price perception of B Corps in lower-income demographics.

Insights from Sects. 4.1 to 4.2 highlight several important aspects: (1) growing consumer demand for conscious providers, (2) a diversification of consumer priorities on what they value when making purchasing decisions, (3) growing greenwashing skepticism due to failed CSR claims, and (4) the need for trustworthy and credible companies that deliver on their commitments. These represent a vast opportunity for B Corps to leverage their certification to reaffirm customer trust, avoid greenwashing skepticism, and highlight their contributions through B Impact Assessment scores.

4.3 Moral Licensing

While an upward trend in ethical consumerism may appear strictly beneficial when taken at face value, its actual effects may be more complex. Behavioral research points to important considerations when evaluating the macro impact B Corp consumerism has on the environment, namely, moral licensing and single action bias. Moral licensing is the idea that a good deed may give individuals leeway to engage in subsequent unethical or immoral behavior.Footnote 142 A similar concept is the single action bias posited by Weber,Footnote 143 which describes how decision-makers faced with a risk are likely to take a single action to reduce it, after which they are far less likely to take further actions. The action taken is not necessarily the best or most effective at achieving their goal, merely the first. Thus, consumers concerned with climate change may shop at a B Corp committed to reducing carbon footprint, consider their dues paid, and feel justified in continuing to engage in other harmful practices. Consequently, a mere increase in the number of B Corp customers is not necessarily reflective of an overall improvement in environmentally friendly actions. As Mazar and ZhongFootnote 144 notice, sustainable products do not automatically imply a greener, better consumer.

Numerous studies have found evidence of moral licensing in social and environmental domains; for example, a controlled field study followed a campaign to reduce water consumptionFootnote 145 and found a successful decrease in water consumption was offset by an increase in electricity consumption by the same households. In a laboratory experiment in which participants shopped in either a green store or a conventional store, Mazar and ZhongFootnote 146 found that green-store shoppers were subsequently less generous and more likely to cheat and steal than their counterparts. Importantly, this effect was found only for those who actually shopped in the store, while mere exposure to the store actually led to more generosity, pointing to the importance of the action itself. Alongside moral licensing, ample evidence has been found for moral cleansing, the desire to perform a good deed after one deemed immoral,Footnote 147 which may lead to an increase of B Corp consumerism. Indeed, a recent study by Schlegelmilch and SimbrunnerFootnote 148 found that people who had recently bought a luxury item, potentially considered wasteful and immoral, donated significantly more than those who had not.

Drawing on research of companies with CSR practices may also shed light on how moral licensing may be displayed by those working for B Corps. List and MomeniFootnote 149 found that, when randomly assigned to different company types, those hired to do a task by a company with notable CSR practices were more likely to misbehave on the job than people hired by companies without them. This was especially the case when CSR practices were framed as prosocial acts of the workers themselves, that is, “a donation to charity on behalf of the worker” rather than “a donation to charity.” Encouragingly, these effects disappeared when participants chose which kind of company they entered into contract with, which may indicate that those choosing to work for B Corps are less likely to use their employment as moral licensing for immoral actions. This finding highlights narratives that conflict with moral licensing, namely consistency and positive spillover effects. The consistency effectFootnote 150 refers to people’s desires to act in ways that are consistent with their long-term goals and personality traits. Thus, those who have strong environmental concerns are more likely to choose actions that are consistent with this ideal rather than using good deeds as justifications for bad ones.Footnote 151 Similarly, positive (and negative) spillover effectsFootnote 152 describe how engaging in one action may act as a gateway for choosing similar actions in the future. These findings suggest that the mere implementation of CSR standards is insufficient to drive positive behavior change but should be matched by strategies to develop intrinsic motivation for prosocial behavior, which leads to consistent prosocial actions.

Overall, a concern for both consumers and workers who engage in ethical behavior is moral licensing (the tendency to feel justified in engaging in an unsustainable behavior after having performed an “ethical” action). However, this phenomenon is paralleled by that of consistency and spillover effects, which may reflect differing underlying values driving one’s action. For example, consumers or workers who engage in sustainable behaviors because of their intrinsic value structure are less likely to engage in moral licensing (and thus exhibit consistent actions). Conversely, those who engage in sustainable behavior as an external social sign of their own virtue are more likely to engage in moral licensing (and thus not display consistent actions). This process is also modulated by individuals’ perceptions of their action: namely, if they view it as commitment to a goal or as incremental progress toward a goal.Footnote 153 If the sustainable action is viewed as a commitment to a goal, they are likely to choose actions consistent with previous ones to honor the commitment. Conversely, if they view it as incremental progress, a feeling of accomplishment might facilitate their moral licensing of a less sustainable choice. Taken together, this highlights the importance of how sustainable choices are presented. B Corps whose pitches appeal to people’s long-term commitment to sustainability and pro-sociality may be more successful in attracting those who have performed similar actions in the past and are driven by intrinsic values.

4.4 Inspiring Consumer Change

This section highlights how B Corps can inspire consumer change by promoting sustainability practices such as degrowth thinking and reduced consumption of unnecessary goods, as well as by applying “nudges”Footnote 154 and other techniques that influence behavior.

4.4.1 Sustainable Mindsets: Degrowth Thinking

Hankammer and colleaguesFootnote 155 advocate for degrowth and identify principles that hybrid companies (which include B Corps) can employ to educate and incentivize consumer behavior. One such principle pertains to promoting social and business acceptance of degrowth thinking—that is, rejecting the idea that continued growth is a prerequisite for success or well-being and supporting a perspective beyond mainstream consumerism and materialism.Footnote 156 Separately, and inspired by Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness measure,Footnote 157 alternative or complementary measures of GDP per capita have been developed, which include psychological health, population health, and sustainability (e.g., the UN Human Development Index; the OECD Better Life Index), among others. Together these suggest a growing awareness of the need to redefine value and wealth beyond economic measures, to include metrics that reflect human and environmental well-being. In this context, B Corps can promote acceptance of degrowth thinking by communicating their corporate values and conducting educational campaigns. Another principle related to degrowth thinking is that of sufficiency; in other words, educating consumers to moderate their net demand of goods and services that are not necessary for survival (e.g., reducing clothing demand, as fast fashion is a major freshwater pollutantFootnote 158). By combining degrowth and sufficiency, B Corps can also help facilitate the reuse and sharing of products in the transition from a linear to a circular economy (e.g., support of the 7R principle: rethink, refuse, reduce, reuse, repair, regift, and recycle).

4.4.2 Capitalizing on Decision-Making Research: MINDSPACE and SHIFT

Based on decades of aggregated decision-making research influenced by both cognitive and affective factors, scholars have formulated two powerful frameworks that can guide interventions on consumer behavior: MINDSPACEFootnote 159 and SHIFT.Footnote 160 MINDSPACE stands for: Messenger, Incentives, Norms, Defaults, Salience, Priming, Affect, Commitment, and Ego; SHIFT stands for: Social Influence; Habit Formation; Individual Self; Feelings and Cognition; and Tangibility. Each of these represent a set of principles that can be implemented at different levels (e.g., social norms, habits) to generate behavioral results with the potential to reduce consumers’ intention-action gap. Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of each framework.

Noticeable overlap exists between the two frameworks; for example, Social Influence, which includes social norms, corresponds to Norms, and Individual Self corresponds to Ego. The scopes of the two frameworks are not mutually exclusive but complementary, each taking slightly different approaches. SHIFT demonstrates a more applied approach (e.g., tangibility, habits), while MINDSPACE focuses more on fundamental modalities underlying information processing (e.g., salience, priming), and both converge on complex information processing (e.g., social influence, affect). While discussing each principle in depth is beyond the scope of this chapter, we will highlight the principles we consider most relevant for B Corps to incorporate into their activities to positively influence consumer behavior. We strongly encourage those interested to read the cited articles for each framework.

4.4.2.1 Social Influence (Messenger and Norms) and the Individual Self (Ego)

The relationship between social norms and internalized values and their influence on acting in accordance with an ideal moral self was already introduced in the context of consumer motivations for B Corps purchases (see Sect. 4.2). These aspects represent a keyway B Corps can inspire consumer change. The B Corp label can encourage consumers who are not intrinsically motivated by ethical consumption to purchase products by appealing to their sense of social identity or community pride (provided they recognize the label and are aware of what it stands for). This behavior is a form of signaling, that is, communicating one’s values and preferences to other community members, thus using the label for its functional utility (gaining social recognition) rather than its intrinsic value. Regardless of motivation, the net result of this kind of behavior is positive. Similarly, consumers who intrinsically value ethical consumption will act according to their idealized self-concept and self-defined moral compass;Footnote 161 therefore, in this case, the label would appeal to consumers’ internal value system and lead to feelings of self-satisfaction or self-interest and help maintain a positive self-concept (again, provided the consumer recognizes the label’s meaning).

A second way social norms can promote change is through peer comparison or peer relatability (which relates back to social identity). For example, when a hotel room displayed a sign asking people to recycle towels, 35% complied; however, when the sign included that most guests recycled towels at least once (thus including a social cue), 44% recycled.Footnote 162 Similar results have been seen in other sectors, including energy saving,Footnote 163 charity donations,Footnote 164 and seatbelt wearing.Footnote 165 By including social norm cues in their promotion, packaging, and websites, B Corps can influence their customers (and consumers who come across the information randomly, for example on social media).

Lastly, messengers, or the parties who deliver the message, have tremendous influence on how much consumers consider and integrate information in their decision-making. Research has identified that signals of authority can influence people both positively (to integrate information) and negatively (to discard it), likely based on one’s personality structure. Other strong influencers include indicators of prestige, socioeconomic status, competence, attractiveness, whether the communicator is similar or an in-group member, and displays of leader vulnerability.Footnote 166 When B Corps engage in public communication or promotion, they can decide what kind of communicator they want to employ, and which factors will influence their audience based on the audience’s aggregate values. For example, if most of the audience is concerned with prestige, they are more likely to integrate information if someone famous supports a sustainable behavior. Likewise, if the audience’s primary concern is environmental conservation, an authority figure (e.g., expert in the field) highlighting tangible actions that can be taken would be more suitable.

4.4.2.2 Feelings and Cognition (Affect)

Just as the assumption decision-making is a purely rational process dictated by utility maximization is incorrect, research has shown that assuming decision-making relies entirely on cognitive processes (and biases) is also inaccurate. Emotions are an integral part of decision-making and affect thinking in several ways, for example by influencing content and depth of thought and goal activation.Footnote 167 Content of thought refers to the type of information emotions elicit at a cognitive level, depth of thought to the thoroughness of analysis incited by different types of emotions, and goal activation to emotions’ ability to activate the desire or motivation to attain a certain goal. Further, emotions can be characterized beyond their valence (i.e., positive or negative); for example, they can be associated with appraisals of high or low certainty (“certainty is the degree to which future events seem predictable and comprehensible”).Footnote 168 Specifically, fear is associated with appraisals of low certainty and anger with high certainty. A low-certainty emotion (e.g., fear) will elicit a systematic and thorough type of thinking, while a high-certainty emotion (e.g., anger or happiness) is more likely to lead to heuristic thinking, thus altering the content and depth of thought. Concerning goal activation, anger represents a powerful catalyst by activating a desire to change a situation.Footnote 169 In the context of B Corp activities, an interesting example is Patagonia’s “The president stole your land” campaign, which was a response to Donald Trump’s reduction of protected national parks land in Utah. It frames the act as an injustice and is likely to trigger the public’s anger and subsequent goal activation, increasing the likelihood that the public will engage in rectifying actions and mount political pressure. Concerning positive emotions, engaging in sustainable behaviors often leads to a “warm glow” (overall positive feelings characterized by the satisfaction and fulfillment of having done something considered good), which leads to perceiving the action in a positive light. Another example is that of pride, which results from achieving something one deems as moral and responsible and relates to the maintenance of a positive self-concept as exemplified in Social Influence (Messenger & Norms) and the Individual Self (Ego). Both pride and warm glow have been identified as precipitants of continued sustainable behaviors.Footnote 170

To summarize, B Corps can strategically design their campaigns (whether promotional or activist) to elicit specific emotions that will shape their consumers’ content and depth of thought and goal activation. For example, in the context of reducing plastic pollution, B Corps can leverage fear of the effects of microplastics on human health to motivate consumers to reduce their plastic consumption and demand, given that fear is characterized by low certainty of future outcomes and can thus promote actions aimed to reduce uncertainty (in this case, reducing consumption). Similarly, B Corps can trigger a sense of pride in consumers who have achieved a specific target, further motivating them to continue engaging in that behavior and maintain a positive self-concept.

4.4.2.3 Commitments and Habit Formation

Behavior change is a resource demanding goal-directed process that requires cognitive control in the form of cost-benefits calculations to estimate optimal choices. Conversely, once a habit has been formed after repeatedly engaging in a goal-directed action through exposure to a cue, actions become automatic (i.e., transitions from a goal-directed system to a less computationally intensive “model free” system)Footnote 171 and bear considerably lower cognitive costs, thus facilitating sustainable engagement. One way to facilitate the habit formation process is by creating commitments that serve as a cognitive guide during goal-directed behavior, potentially increasing the likelihood of sustained sustainable behaviors. B Corps can leverage three techniques to promote both commitments and habit formation: (1) prompts/nudges (succinct messages about what ought to be done to achieve a goal); (2) targeted incentives (e.g., rewards, gifts, matching donation schemes); and (3) feedback that positively reinforces a consumer behavior (e.g., through personalized consumer messages). All of these can be successfully implemented in addition to social comparisons. For example, a prompt can say “60% of our customers have reduced their plastic use by switching to our reusable water bottles” or, to increase relatability, “70% of customers in your age group have switched to reusable water bottles.”

4.4.2.4 Decision Fatigue, Priming, and Salience

The phenomenon of choice overload has been widely documentedFootnote 172 and refers to the diminishing returns of increasing choice; in other words, there is an optimal point at which multiple options are beneficial, after which having many options becomes detrimental and has been associated with dissatisfaction and decision avoidance and paralysis.Footnote 173 With numerous brands claiming various degrees of CSR and with consumers unsure which are genuine or not, having an easily perceivable and trustworthy visual cue can facilitate decision-making. Here, priming is achieved through repeated exposure to the B label or B Corp-related visual cues. After repeated priming to this cue, it is likely the label will become more salient (i.e., more easily recognizable and evident). Thus, the B label can guide ethics-concerned consumers into choosing a product more easily and serve to mitigate the costs of choice paralysis and avoid decision fatigue. B Corps can ensure they routinely prominently display the certification and do their best to prime their consumers with related visual cues that create positive associations (e.g., a smiley face, a green symbol, or succinct information about CSR achievements in addition to the label).

4.5 Exploring Public Awareness and Perceptions of B Corps

Public awareness is paramount to ensuring the success of the B Corp movement: if consumers do not recognize the B certification label, the behavioral phenomena outlined above are unlikely to be effective, as consumers would not be able to use recognition or rely on take-the-best heuristics. To date, there has been only one estimate of public awareness of B Corps, which resides at an astonishingly low of 7% in 2017,Footnote 174 far from levels required to capitalize on the aforementioned benefits. The lack of awareness on what a B certification means can impact several other factors, such as perceptions of trustworthiness or, inversely, greenwashing skepticism, thus undermining one of the main motives for establishing standards, as discussed at the end of Sect. 1. As already mentioned, trust is paramount to building mutual and lasting relationships with all concerned stakeholders. It follows that if consumers intuitively perceive the B label as a marketing gimmick to sell more under the guise of sustainability, the movement’s future development will be negatively impacted. Likewise, without a nudge to incentivize consumers to switch to more sustainable alternatives, they are likely to continue using the default or status quo option. Thus, both recognition and trust of the label are necessary for adoption and successful nudging. B Corps could learn from other types of labeling, such as “bio” or “organic” labels in the food industry, for which marketing studiesFootnote 175 demonstrated a significant relationship between the use of food labels, knowledge, and consumer choice. Further, no research to date has investigated public perceptions of trust and greenwashing concerning B Corps nor compared perceptions of B Corps and other types of companies (specifically, for-profit companies with generic CSR programs). Thus, we conducted a survey to generate novel data to evaluate these aspects. The sections that follow discuss the survey methods, results, and implications.

4.5.1 Materials and Methods

We implemented an online survey in the UK and US with 620 participants (recruited via the online platform ProlificFootnote 176). Of these participants, 312 were in the UK (MedianAge = 41.7, MinAge = 18, MaxAge = 73, SDAge = 13.8, 49.3% female) and 308 in the US (MedianAge = 33, MinAge = 18, MaxAge = 80, SDAge = 14.3, 48.7% female). The survey comprised several sections, including: (1) a sociodemographic questionnaire; (2) a 7-point Likert scale to measure self-reported B Corp familiarity; (3) an objective knowledge quiz about B Corps; (4) a 7-point Likert scale to measure perceptions of whether B Corps provide societal benefits, as well as their perceived trustworthiness and likelihood to engage in greenwashing compared to for-profit companies with CSR policies, and (5) what factors (e.g., better environmental practices, ethical treatment of labor force, transparency, etc.) would be important to respondents when choosing a company’s product/service. Between sections (3) and (4), participants were presented with detailed information on B Corps (and its distinction from benefit corporations), alongside a short video summarizing what a B Corp is. In the middle and at the end of the survey, participants had the opportunity to answer an open question regarding their general perceptions of B Corps. The online survey was designed in PsytoolkitFootnote 177 and can be accessed online.Footnote 178

4.5.2 Results and Discussion

4.5.2.1 Public Awareness

Consistent with the previous data,Footnote 179 our results showed that familiarity with B Corps is still low: across both samples, only 15% of the respondents agreed (with just 3.5% strongly) with the statement, “I am familiar with B Corps,” while the majority (83%) disagreed. However, although still low, this result indicates that public awareness of B Corps has slightly increased compared to the 2017 survey. The lack of familiarity with B Corps was further reflected in the questions measuring participants’ level of knowledge of B Corps. In a multiple-choice question where participants had to choose three out of five statements that correctly defined B Corps, fewer than 3% identified all three, and only 15% identified at least two, with the rest identifying a mixture of both correct and incorrect answers. It was also reflected in additional qualitative data obtained through participants’ open-ended responses, which indicated they desired more access to information about B Corps, for example: “I wish there was more outreach to the public to understand which companies have this and which do not”; “I had never heard of them before this study - I am unsure if they are more common in the USA? There is a risk that, with a combination of other ethical standards, that the impact could be diluted by the presence of others (e.g. fair trade etc.)”; “Often as a consumer, it is hard to distinguish what aspects of production are genuinely ethical and what is ‘just for show.’” In sum, our results highlight that more work needs to be done by B Lab, B Corps, and other similarly oriented social enterprises to extensively engage with consumers to raise awareness on these new types of purpose-driven agents, their importance for society in promoting sustainable practices, and for other businesses considering becoming certified.

4.5.2.2 Perceptions of Societal Benefit, Trustworthiness, and Greenwashing

Despite most respondents’ lack of knowledge on B Corps, they tended to have a positive perception of B Corps. After being provided with a description of what B Corps are and what their ethos is (via a freely available video paired with descriptions), the vast majority (74%) indicated they believed B Corps are beneficial for society. Similarly, 60% of participants reported they believed B Corps could be instrumental in improving business ethics practices. Participants also indicated a preference for B Corps over standard for-profit companies with CSR policies regarding trusting their products or services and said they found B Corps more credible.Footnote 180 This higher credibility and trustworthiness was further corroborated by responses on the extent participants believed B Corps’ CSR policies were genuine or merely greenwashing: 55% of respondents indicated they believe them genuine. Despite these positive perceptions, when asked directly whether these practices were used instrumentally for financial gains, only 42% of participants disagreed, suggesting a majority are either unsure or actively believe so. Interestingly, we found a significant gender difference,Footnote 181 with men more likely to distrust B Corps’ intentions compared to women. Footnote 182 Lastly, when asked to rank from most to least likely to engage in greenwashing (between four options: B Corps, benefit corporations, standard companies with CSR policies, and social enterprises), 67% of participants ranked B Corps as their third or fourth options, and 63% of participants ranked standard companies with CSR policies as their first or second most likely to greenwash.Footnote 183 These somewhat mixed resultsFootnote 184 indicate that better communication on what B Corps are, how compliance with standards is determined, and the motivations of entrepreneurs behind purpose-driven businesses, is necessary to decrease the risk of B Corps misperceptions, which could potentially impact their credibility and success.

4.5.2.3 Important Factors Consumers Consider When Purchasing from B Corps

In our survey, we also investigated what motivated participants to purchase from B Corps. We found that besides price and quality, environmental, ethical, and social concerns were among the most important factors: 61% were motivated by ethical treatment of labor force, 58% by better environmental practices, 49% by transparency, 36% by locally produced (if goods), 24% by social/environmental activism, and 18% by customer education on sustainable practices. These results are consistent with information presented in Sect. 4.1. Furthermore, we found a significantFootnote 185 gender difference on factors considered most relevant: women were more likely than men to consider (1) ethical treatment of labor force, (2) customer education on sustainable practices, and (3) social/environmental activism when evaluating which brand to purchase from. These results are in line with literature showing that women exhibit more sustainable behaviorsFootnote 186 and help explain the finding that women are more likely to seek a B Corp certification for their businesses.Footnote 187

4.5.2.4 Qualitative Responses

Despite an overall inclination by participants to trust B Corps more than for-profit companies with CSR policies, some remained skeptical toward this type of social enterprise. Several participants expressed strong views in optional open-answer feedback questions, for instance: “B Corp seems like a new way to spin CSR with maybe little to no actual positive externalities”; “Getting logos on goods is a favourite marketing strategy. It’s mostly to fool the customer”; “I am very cynical of these kinds of schemes”; “Never heard of B Corps, but all for profit companies put profit first. Most engage heavily in marketing, including greenwashing. None can be trusted”; “Most corporations, no matter what they say, are always in it purely for profit”; “I feel that a lot of companies jump on the ‘going green’ bandwagon for the wrong reasons and to profit from it.” Others also expressed distrust in relation to price: “My concern that B Corps will use their environmental credentials as an excuse to put a higher price on a product that is ‘saving the planet’”; “I’m not interested in paying more money to subsidise a marketing gimmick.” These attitudes reflect the damage that instrumental CSR and greenwashing have done at a public level and further supports the need for public education campaigns to restore trust discussed throughout the chapter.