Abstract

This chapter develops a theoretical framework for conceptualising adult education’s role in individual empowerment using a capability approach perspective. It also provides empirical evidence on how adult education can contribute to individuals’ empowerment. Adult education is both a sphere of, and a factor for, empowerment. Empowerment through adult education is embedded in institutional structures and socio-cultural contexts and has both intrinsic and instrumental value; it is neither linear nor unproblematic. Adult education’s empowerment role is revealed in expanded agency; this enables individuals and social groups to gain power over their environment. Using quantitative and qualitative data, the chapter shows that participation in non-formal adult education can empower individuals, increasing their self-confidence, capacity to find employment, and to control their daily lives.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has recently been growing research interest in going beyond the instrumental and economised understanding of adult and lifelong education and learning and focusing on its empowerment potential (Baily, 2011; Fleming & Finnegan, 2014; Fleming, 2016; Tett, 2018). Attempts have also been made to provide a more comprehensive view of the mission and roles adult education serves by revealing its substantial transformative power at both the individual and societal levels (Boyadjieva & Ilieva-Trichkova, 2021). In addition, policy documents have been published which not only acknowledge the complexity of adult educational goals and the contributions made to individual and societal development, but also explicitly emphasise the emancipatory role that lifelong learning can play. Thus, according to UNESCO’s Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education of 2015 (UNESCO, 2016), the objectives of adult learning and education are: ‘to equip people with the necessary capabilities to exercise and realise their rights and take control of their destinies… to develop the capacity of individuals to think critically and to act with autonomy and a sense of responsibility’, and to reinforce their capacity not only to adapt and deal with but also to ‘shape the developments taking place in the economy and the world of work’ (art. 8 and 9, italics added). However, more research is needed in order to better conceptualise and empirically demonstrate the complexity of the empowerment potential and implementation of adult education in different socio-cultural contexts.

Against the above background, this chapter contributes to the discussion of the relationship between adult education and empowerment, thus further developing one of the main arguments of the present book: that there are multiple benefits to lifelong learning and adult education for individuals and societies, and they should not be restricted to delivering requisite skills to the workforce. It also enriches the understanding of the concept of bounded agency (Rubenson & Desjardins, 2009) by demonstrating, firstly, that the process of empowerment through adult education is not a linear or unproblematic one and, secondly, that only in some cases can the benefits from adult education lead to empowered agency. More concretely, the objective of this chapter is twofold. On the one hand, it seeks to outline a theoretical framework for conceptualising the role of adult education in individual empowerment from a capability approach perspective. On the other, it aims to provide some empirical evidence about how adult education can contribute to individuals’ empowerment. To that end, we argue that adult education is a distinct sphere of empowerment. At the individual level and from a capability approach perspective, empowerment in and through adult education is a process of expanding both agency and capabilities, enabling individuals to gain power over their environment as they strive for their own well-being and a just social order. As a process, empowerment is embedded in the available opportunity structures.

The chapter proceeds as follows. First, we present our conceptual framework by briefly reviewing different approaches towards the understanding of empowerment and highlighting ideas which are relevant to discussions on (adult) education. Then, we outline an empowerment perspective towards adult education within the theoretical framework of the capability approach. A description of the data (both quantitative and qualitative) and methods as well as a presentation of the results follow. Finally, these results are discussed in light of previous research, and some directions for future research and policy implications are outlined in the conclusion.

Theoretical Considerations

Empowerment as a Contested Concept

Many studies—and Chap. 2 of this volume, as well—have emphasised that the notion of empowermentFootnote 1 is inherently complex and open to many interpretations, that there are internal contradictions in this concept, and that it remains under-theorised and contested (Samman & Santos, 2009; Monkman, 2011; Pruijt & Yerkes, 2014; Unterhalter, 2019). Some of the problems and confusion which prevent our understanding of empowerment arise from the fact that its ‘root-concept – power – is itself disputed’ (Rowlands, 1995, p. 101).

Unterhalter (2019, p. 86) traces the history of the use of the word empowerment back to the mid-seventeenth century, outlining that this historical detour highlights ‘that empowerment as a concept can be deployed in multiple ways’. The concept was later firmly established by radical social movements, especially women’s movements, and feminist theorists starting in the 1970s. It has mainly been used to delineate personal and collective actions for justice and the processes of participatory social change which challenge both existing power hierarchies and the relationship between inequality and exclusion (Batliwala, 1994, 2010; Unterhalter, 2019). It has been argued that, over the last 30 years, the concept of empowerment has undergone some distortion, becoming ‘a trendy and widely used buzzword’ (Batliwala, 2010, p. 111). Batliwala (2010, pp. 114, 119) claims that the dominance of neo-liberal ideology has led to ‘the transition of empowerment out of the realm of societal and systemic change into the individual domain—from a noun signifying shifts in social power to a verb signalling individual power, achievement, status’. Some authors argue that empowerment in itself is ‘a disguised control device’, one ‘fraught with contradictions’ stemming from its essence as an asymmetrical relationship (e.g. Pruijt & Yerkes, 2014, pp. 49–50). Empowerment is also viewed as a power relationship which remains, even when the will to empower is well-intentioned, ‘a strategy for constituting and regulating the political subjectivities of the “empowered”; and furthermore, “the object of empowerment is to act upon another’s interests and desires in order to conduct their actions toward an appropriate end”’ (Cruikshank, 1999, p. 69). In a similar vein, Pruijt and Yerkes (2014) identify three challenges associated with empowerment as an asymmetrical relationship: level of control, programmed failure, and risk of stigmatisation. Thus, for example, they argue that ‘an empowerment frame can entice people to start on an impossible mission that can end with them blaming themselves for problems beyond their control’ and that often ‘those to be empowered are deemed to be lacking in autonomy or self-sufficiency’, which entails a risk of stigmatisation (Pruijt & Yerkes, 2014, p. 51).

In a comprehensive review of works on empowerment, Ibrahim and Alkire (2007) systematise 29 understandings of the concept used in the period from 1991 to 2006. These definitions of empowerment differ in terms of the theoretical frameworks they have been elaborated in, the levels they refer to (individual and/or collective), and their scope (processes but also activities and outcomes). All of the above clearly demonstrates that empowerment—both as a concept and a practice—needs to be very carefully studied and re-thought based on fresh theoretical ideas, taking into account its specificity in different social spheres as well as socio-cultural and political contexts. It is very important to emphasise that ‘although different kinds of empowerment may be interconnected, empowerment is domain specific’ (Ibrahim & Alkire, 2007, p. 383). This means that in order to be thoroughly understood, empowerment should be analysed in respect to different domains of life whilst acknowledging their specificity. Thus, for example, empowerment in education is not only related to empowerment at work or in public life but may also differ from them. Revealing this difference is a sine qua non for grasping its meaning and path towards accomplishment.

Theorising the Relationship Between Empowerment and Education

As Unterhalter (2019, p. 75) acknowledges, ‘the relationship between empowerment and education is neither simple nor clear’. She concludes that education ‘can be positioned as an outcome of empowerment or as a process associated with its articulation’ (Unterhalter, 2019, p. 80).

The diversity of theoretical approaches which could be applied towards an understanding of the relationship between empowerment and education is clearly evident in the special ‘Gender, education and empowerment’ issue of the journal Research in Comparative and International Education, published in 2011. Various authors there use Stromquist’s (1995) model of empowerment, which consists of four necessary components: cognitive, psychological, political, and economic. Still others try to reveal the three dimensions upon which Rowlands’s (1995) empowerment operates—the personal, where empowerment is about developing a sense of self and individual confidence and capacity; that of close relationships, where empowerment is about developing the ability to negotiate and influence the nature of those relationships and the decisions made within them; and the collective, where individuals work together to achieve more extensive impact than they could alone. The issue features articles based on Cattaneo and Chapman’s (2010) Empowerment Process Model, articulating empowerment as an iterative process whose components include personally meaningful and power-oriented goals, self-efficacy, knowledge, competence, and action, as well as Rocha’s model (1997), which presents the empowerment process as a ladder moving from individual to community. Furthermore, several authors have used the capability approach (Sen, 1999; Nussbaum, 2000). It is important to note that there are some crucial points regarding the relationship between empowerment and education which the studies in this issue agree upon: ‘education does not automatically or simplistically result in empowerment; empowerment is a process; it is not a linear process, direct or automatic; context matters; decontextualized numerical data, although useful in revealing patterns and trends, are inadequate for revealing the deeper and nuanced nature of empowerment processes; individual empowerment is not enough; collective engagement is also necessary; empowerment of girls and women is not just about them, but perforce involves boys and men in social change processes that implicate whole communities; it is important to consider education beyond formal schooling: informal interactional processes and multi-layered policy are also implicated’ (Monkman, 2011, p. 10). Taking into account these outlined characteristics of the relationship between empowerment and education, we will try to delve further and present a more sophisticated understanding of this relationship within the framework of the capability approach.

The Capability Approach Towards the Relationship Between Empowerment and (Adult) Education

The capability approach is a social justice normative theoretical framework for conceptualising and evaluating phenomena such as inequalities, well-being, and human development. According to the capability approach, it is not so much the achieved outcomes (functionings) that matter; rather, one’s real opportunities (capabilities) determine whether those outcomes can be achieved. For Sen, capabilities are freedoms conceived as real opportunities (Sen, 1985, 2009). More specifically, ‘capabilities as freedoms’ refer to the presence of valuable options—in the sense that opportunities do not exist only formally or legally but are also effectively available to the agent (Robeyns, 2013).

There are three strands of research relevant to any attempt at understanding the relationship between empowerment and (adult) education from a capability approach perspective. The first one discusses the meanings of empowerment by drawing on different concepts associated with the capability approach, but it does not reflect upon any possible connections between education and empowerment (e.g. Alsop et al., 2006; Ibrahim & Alkire, 2007; Samman & Santos, 2009). The second strand includes literature on education and empowerment, also often referring to the debate over capabilities and empowerment (e.g. Loots & Walker, 2015; Monkman, 2011). The third strand comprises studies which aim to reveal the heuristic potential of the capability notion in understanding the relationship between empowerment and education (e.g. DeJaeghere & Lee, 2011; Seeberg, 2011; Unterhalter, 2019).

Based on this literature, we define empowerment in and through (adult) education from a capability approach perspective as an expansion of both agency (process freedom) and capabilities (opportunity freedom). Empowerment and adult education have one characteristic in common: neither is a single act, but they are rather lifelong processes embedded in the available institutional structures and socio-cultural context. The empowerment role of (adult) education is purposeful and matters both intrinsically and instrumentally. Empowerment in and through (adult) education is closely related, but not identical, to agency enhancement. It is not only an expanded agency but one which has a clear goal—gaining control over an individual’s environment with the aim of improving their own well-being and that of society. The empowerment role of (adult) education has two sides: a subjective one, referring to an individual’s capability to gain control over the environment, and an objective one, reflecting the available opportunity structures.

Adult Education as a Sphere of Empowerment

Alsop et al. (2006, p. 19) identify three domains, divided into different subdomains, in which empowerment can take place—the state (justice, politics, and public service delivery); the market (labour, goods, and private services); and society (intra-household and intra-community). We argue that (adult) education can be defined as a specific, complex subdomain of empowerment which functions at the intersection of all three domains: the state, the market, and society. (Adult) education can be a public service, but it is also a good—both private and public—which is firmly embedded in the dominant social hierarchies, institutional and cultural norms, community, and societal milieu.

In conceptualising (adult) education as a sphere of empowerment, we have drawn upon the heuristic potential of Sen’s concept of conversion factors and the crucial significance of context for agency within the capability approach (Sen, 1985, 1999; Nussbaum, 2000). Conversion factors are defined as a range of factors influencing how a person can convert the characteristics of his/her available resources (initial conditions) into freedom or achievement. The empowering role of (adult) education depends on and is realised through the very way it is established and organised in a given society. That is why revealing and evaluating the empowerment role of adult education requires ‘understanding the contexts of learning, teaching, and education governance, considering whether the content of education encourages an individualistic or an inclusive and solidaristic sense of agency’, and looking ‘both at organisations and the norms that govern them’ (Unterhalter, 2019, p. 93).

At first glance, it seems that the role of adult education (viewed as a sphere and an outcome) for the subjectivity and agency of individuals would be less pronounced in adult students than teenagers. However, this statement does not take into account essential changes in systemic-structural characteristics of contemporary societies or the individual’s role in shaping them. The societies of late modernity feature changes, turning from sporadic occurrences into a permanent fixture, in both their existence and the lives of individuals (Bauman, 1997). Changes in the main characteristics of these societies will inevitably generate significant changes in the way individuals relate to their own lives, models of personal realisation, and long-term plans. Such life plans and goals are becoming increasingly hard to pursue, and the paths taken by individuals do not often follow single projects but rather increasingly become a matter of self-building—wherein the goals at one stage of a person’s development may not necessarily accrue upon the goals of preceding stages, quite possibly taking a very different turn (Bauman, 2002, pp. 433–434). Thus, throughout their lives, people are confronted with the need to (re)build their identity and subjectivity.

Adult Education as a Factor for Empowerment

Adult education can function as a factor for empowerment at three levels—individual, collective/group, and societal.

At an individual level, empowerment through adult education relates to its role in further developing individual capability sets, thus increasing their potential to make high-quality choices and allowing them the freedom to act. As already outlined, empowerment is not about expanding agency for any purposes or developing any capabilities—it is about developing capabilities that enable engagement in social change processes. Unterhalter (2019, p. 80) argues that ‘the capability approach provides some important additional conceptual connections that help link empowerment more closely to ideas about social justice and an understanding of the institutional space in which this is to be achieved’. She also emphasises, ‘for Sen, agency (and by implication empowerment) is not mere self-interest, but an expression of a sense of fairness for oneself and due process for oneself and others’ (Unterhalter, 2019, p. 91).

At a collective/group level, adult education can empower different social groups, especially vulnerable ones, by helping them to organise and express their interests and to achieve upward mobility.

At a societal level, empowerment through adult education reflects the role of education towards achieving important public goods—such as social equity, trust, and environmental conservation—and thus making the world a better place to live in. According to Sen (2009, p. 249), development is ‘fundamentally an empowering process’, and one of its important aims is to preserve and enrich the environment. Education plays a crucial role in this empowering process, as ‘the spread of school education and improvements in its quality can make us more environmentally conscious’ (Ibid).

Intrinsic and Instrumental Value of the Empowerment Role of Adult Education

The capability approach requires looking beyond achievements and relating the real freedoms or opportunities an individual has to the ‘goals or values he or she regards as important’ (Sen, 1985, p. 203). As far as adult education can have both intrinsic and instrumental value, its empowerment role also matters both intrinsically and instrumentally. Empowerment through adult education has intrinsic value: similarly to agency (Sen, 1985), it is the result of a ‘genuine choice’ made by a ‘responsible agent’, and as such, this is an important end in and of itself. Instrumentally, empowerment through adult education matters because it can serve as a means to develop other capabilities and achieve different outcomes.

The Role of Non-formal Adult Education for Increasing Individuals’ Agency Capacity: An Empirical Study

The next part of the chapter is empirically based and focuses only on two aspects of the very complex relationship between empowerment and adult education, outlined in the theoretical discussion. More concretely, we will analyse the influence of participation in non-formal adult education on the subjective side of the empowerment role of adult education, that is, on individuals’ capacity to act through increasing their self-confidence and capacity to control their daily life.

Data and Empirical Strategy

The empirical basis of our study is the Adult Education SurveyFootnote 2 (AES) and some interviews. The Adult Education Survey, conducted via random sampling procedure, targets people aged 25 to 64 who live in private households. So far, this survey has been conducted three times: in 2007, 2011, and 2016. However, 2007 was the only year in which questions about attitudes towards learning were included. The number of countries participating in the 2007 Adult Education Survey was 29. However, data on attitudes are available for just 13 of those (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia). Depending on the variable of interest, this data could also be found for 14 (+Poland) or 15 countries (+Poland and the United Kingdom). For that reason, the following analysis is based on data for the above-listed countries. In terms of the overall quality of data, it is worth mentioning that the Synthesis Quality Report (Eurostat, 2010) evaluated the Adult Education Survey positively. Classification regarding education follows the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) revision of 1997.

In addition, some qualitative data from interviews with young adults involved in adult education programmes will also be presented. As there are only a limited number of interviews that were carried out within the Enliven project, we have used quotations from these interviews mainly to illustrate the results obtained based on qualitative data. The fieldwork was conducted on 28 May 2018 in a small city in Bulgaria. Seven in-depth interviews, based on a preliminary scenario, were conducted: five with participants from low-income households in the Roma ethnic community lacking education and work experience; one with a staff member running the programme (the school principal); and one with a representative at the level of the learning setting (a teacher).

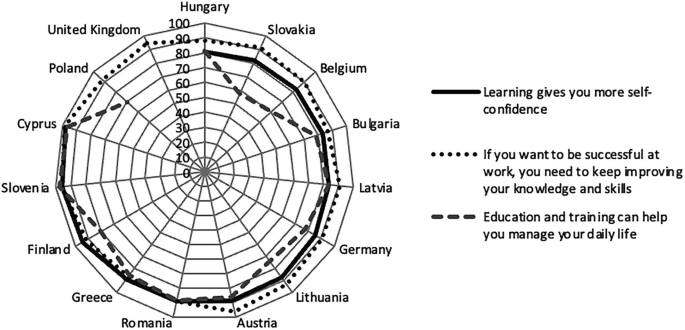

We measured self-confidence via two indicators: ‘Learning gives you more self-confidence’ and ‘If you want to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills’. One indicator was used to measure the capacity to control one’s daily life: ‘Education and training can help you manage your daily life’. These indicators represent respondents’ subjective perceptions and make up our dependent variables, which we measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Fully agree) to 5 (Totally disagree). However, for the needs of our analysis, the scale for each dependent variable was dichotomized into two values: 1, which includes the answers ‘Agree’ and ‘Fully agree’, and 0, which includes the remaining three answer options.

We used multi-level modelling to analyse the three dependent variables. Given that our dependent variables are binary, we used two-level random intercept logistic models. We also used the xtlogit command in Stata 14. More specifically, we estimated three model specifications for each dependent variable. This was done in order to see whether the effects of the different variables changed when additional variables were included. Model 0 is our (unconditional) baseline model containing the intercept (constant) only. Model 1 includes our main independent variable—participation in non-formal education or training (NFET) in the previous 12 months (dummy ref.: no = 0, yes = 1). We also included the highest educational level (three categories, ref.: ISCED 0–2 = low, ISCED 3–4 = medium, and ISCED 5–6 = higher) because previous research has clearly shown that participation in adult education strongly depends on the level of educational attainment (Roosmaa & Saar, 2012; Boyadjieva & Ilieva-Trichkova, 2021). In Model 2, we included an interaction term between the highest educational level and participation in NFET in order to determine whether the effect of NFET on the three dependent variables differed according to adults’ educational levels. To account for differences in the composition of different groups of adults, all our specifications were made to control for: educational background (dummy ref.: 0 = no parents had higher education [low]; 1 = at least one parent had higher education [high]); gender (dummy ref.: 0 = male; 1 = female); and main activity (ref. employed; 1 = unemployed, or 2 = inactive).

Following Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal (2012), we interpreted the odds ratios conditionally on the random intercepts of the models. The odds ratio is the number by which we multiplied the odds of agreeing with our three indicators for measuring self-confidence and control over everyday life for every single-unit increase in an independent variable, for example, participation in non-formal adult education. We interpreted an odds ratio greater than 1 as the increased odds of agreement with a certain statement along with the independent variable, whereas an odds ratio of less than 1 indicated decreased odds when the independent variable increased. Given that most of our independent variables are dummy and categorical, we compared the odds of each statement category with one which we chose as a reference.

How Learning Matters to Adults’ Agency Capacity

We begin with a look at the distribution of dependent variables in 13–15 European countries. Figure 7.1 shows the proportions of those agreeing with the three statements of interest. Overall, the majority of adults have a very positive attitude towards learning and they think that it gives them more confidence, regardless of their country of residence. The same is also true for the attitude that people who want to be successful need to keep improving their knowledge and skills—even to a slightly higher extent in almost all countries apart from Finland, Greece, Romania, and Slovenia. The majority of adults in all countries agreed that education and training could help them manage their daily life, although to a lesser extent compared to the previous two statements.

We now proceed to a more detailed discussion, based on multivariate analyses, of the three benefits of participation in non-formal adult education. Model 1 in Table 7.1 indicates that participation in NFET was positively associated with adults’ perceptions that learning provides more confidence. More specifically, the odds of agreeing with this statement are about 1.7 times greater for adults who had participated in NFET in the previous 12 months than for those who had not taken part in such an activity. There are also clear differences between adults according to educational level. The higher their attainment of education, the higher the conditional odds were of agreeing that learning gives you more self-confidence. The estimates in Model 2 are consistent with those from Model 1, and we could still observe the positive link between higher educational attainment and participation in NFET in the last 12 months and adults’ attitudes that learning provides more confidence. It is important to emphasise that the influence of NFET on this attitude differed among adults with varying levels of education. Namely, this influence was less pronounced among those with medium and higher education levels than those with lower levels of education. More specifically, having participated in NFET is significantly associated with relatively lower conditional odds of agreeing that learning provides more confidence among adults with medium and higher educational levels.

We carried out interviews with young adults who were illiterate or had completed only primary education. Those who had passed literacy programmes felt more satisfied, independent and confident:

-

Interviewer: ‘How do you feel now? Do you have a higher level of self-confidence?’

-

Respondent: ‘Yes, I feel good about it. Even when they evaluated me, I felt really happy.’ [BG2_P5_108]

-

Respondent: ‘It was really pleasant. I actually liked it. I’m satisfied.’ [BG2_P1_147–148]

The interviews with other young adults with lower literacy rates also confirmed that their decisions to be involved in adult education had been informed by a desire for their capabilities as human beings to be recognised and to develop their own abilities in order to improve self-identity and contribute to the flourishing of others.

Participation in NFET also demonstrated a positive link with adults’ likelihood to agree that in order to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills. More specifically, Model 1 in Table 7.2 indicates that the conditional odds of agreeing with this statement were about 2 times greater for adults who had participated in NFET in the previous 12 months than for those who had not taken part in such an activity. It also shows that there are clear differences between adults, depending on their educational levels, in terms of attitudes about whether the constant improvement of knowledge and skills is important for success at work. The higher the educational level, the higher the odds were of agreeing that people’s improvement of knowledge and skills was a prerequisite for success at work, given the other covariates. The estimates in Model 2 are fairly consistent with those in Model 1—an interaction term was added between the highest educational attainment and participation in NFET. Our analysis shows that having participated in NFET was significantly associated with relatively lower conditional odds of agreeing that ‘If you want to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills’ among young adults with medium and higher levels of education.

The positive association between participation in NFET and the importance given to improving knowledge and skills as a prerequisite for success at work is furthermore clearly visible in the following quotations from our interviews with young adults:

-

Interviewer: ‘How has participating in the programme changed your life?’

-

Respondent: ‘What’s changed, really, is that now I know more and things are clearer to me… And I want to continue studying… I’d really like to get a license for a car – a driver’s licence. I’d feel a little better at least having my diploma. Everyone thinks they can go out and find a job, no problem. It’s not such a big deal after all, completing 7th grade, but every place wants a diploma now.’ [BG2_P1_129–139]

-

Respondent: ‘Nothing happens without an education.’ [BG2_P2_42]

Participation in NFET also had a positive influence on the likelihood adults to agree that education and training can help you manage your daily life holding all other variables constant. More specifically, Model 1 in Table 7.3 shows that the odds of agreeing with this statement were about 1.4 times greater for adults who had participated in NFET in the previous 12 months than for those who had not taken part in such an activity. There are also clear differences among adults, depending on their educational levels, in terms of their degree of agreement that education and training help them to manage their daily lives. The higher the educational attainment, the higher the odds were of agreeing that education and training could help one to manage their daily life. The estimates in Model 2 are consistent with those from Model 1, and we can still observe the positive association between formal education and participation in NFET in the last 12 months and the attitudes about the role of education and training in managing one’s daily life—we added an interaction term between the highest educational level and participation in formal and NFET. In a similar way to the other two dependent variables, the results here show that the influence of NFET varies among adults with different levels of education. So, it follows that this influence was lower among those with medium and higher education levels than among those with low levels of education.

The positive association between participating in NFET and beliefs that education and training could help one to manage their daily life is further illustrated here:

-

Interviewer: ‘Did you volunteer for the programme?’

-

Respondent: ‘Yes, voluntarily, because they didn’t want to hire me because I am illiterate. And also [because I want] to be literate, not to be cheated with the bills, to understand numbers, to understand what is written.’ [BG2_P5_38–44]

-

Interviewer: ‘What motivated you to participate in the programme?’

-

Respondent: ‘I want to get my driver’s license, since I have a small child who’s starting kindergarten, then school. I think we’ll have to travel a long way away because we’re from the ghetto. I’d still like for my kid to learn in Bulgarian.’ [BG2_P3_91–93]

The Need to Rethink Adult Education Policies

The present chapter enriches the critical perspective adopted by this book and the Enliven project by outlining a theoretical framework for conceptualising the role of adult education for individuals’ empowerment from a capability approach perspective. The study contains both theoretical and methodological contributions. At the theoretical level, it argues that adult education should be regarded as both a sphere of and a factor for empowerment. Empowerment through adult education is embedded in the available institutional structures and socio-cultural context, and it matters both intrinsically and instrumentally. The empowerment role of adult education is revealed through agency expansion, which enables individuals and social groups to gain power over their environment in their striving towards individual and societal well-being. At the methodological level, to the best of our knowledge, this chapter offers the first attempt to investigate the importance of adult education in empowerment by using quantitative data from a large-scale international survey. Our analyses show that participation in non-formal adult education is viewed as a means for empowering individuals through increasing their self-confidence and their capacity to find a job and to control their daily life.

Despite wide-ranging criticism, adult education policies have recently been dominated by vocationalisation, instrumental epistemology (Bagnall & Hodge, 2018), and the prioritisation of ‘learning as performance over the holistic educational formation of a person’ (Seddon, 2018, p. 111). The empowerment perspective helps to reveal one very often overlooked part of these narrow, deficient aspects of contemporary adult education policies. We are referring to the often neglected role of adult education in the formation of individual agency, self-confidence, and capacity to control one’s environment.

This chapter has shown that the relationship between empowerment and adult education policies and practices should be regarded as a complex field of study. There is a need for future in-depth inquiries into a number of theoretical and methodological issues, including: (i) how the empowerment role of adult education differs in various socio-economic contexts and how to explain transnational differences; (ii) which dominant cultural norms in different countries impede parity of participation in adult education and its empowerment role; (iii) how the empowerment role of adult education is manifested in formal and non-formal adult education; (iv) how to develop policies aimed at enhancing the role of adult education in the formation of individual agency, self-esteem, and self-confidence; (v) how to produce reliable data in order to study the relationship between empowerment and adult education; (vi) what kinds of methodological instruments may be needed to reveal different aspects of the relationship between empowerment and adult education; and vii) what kinds of objective indicators could be used for measuring the empowerment role of adult education.

Tett (2018, p. 362) mentions that in the league tables produced by international organisations such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC), ‘attention is paid only to economic (or redistributive) aspects of inequality and both the cultural (or recognitive) aspects and also the participative (or representative) are ignored’. This conclusion can be extended to the Adult Education Survey, as well. In fact, the 2007 pilot Adult Education Survey survey included a special section on ‘Attitude towards learning’ that was comprised of eight questions.Footnote 3 Unfortunately, these and a number of other attitudinal questions were left out of the subsequent surveys conducted in 2011 and 2016.

Our analysis has demonstrated that the empowerment effect of adult education is greater among learners with low educational levels than it is among those with medium and higher educational levels. This means that in order to truly be sensitive towards vulnerable groups, adult education policies have to more seriously consider the varying roles adult education can play in the empowerment of people from different social backgrounds.

Notes

- 1.

‘To “empower” as a neologism was first used in the mid-seventeenth century in England in the context of the Civil War… the first uses of the term in 1641, 1643, and 1655 all refer generally to men being “empowered” by the law or a supreme authority to do certain things’ (Unterhalter, 2019, p. 80).

- 2.

This chapter uses data from Eurostat, AES, 2007, obtained for the needs of Research Project Proposal 124/2016-LFS-AES-CVTS-CSIS. The responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors.

- 3.

More specifically, adults were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: ‘People who continue to learn as adults are more likely to avoid unemployment’; ‘If you want to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills’; ‘Employers should be responsible for the training of their employees’; ‘The skills you need to do a job can’t be learned in the classroom’; ‘Education and training can help you manage your daily life better’; ‘Learning new things is fun’; ‘Learning gives you more self-confidence’; & ‘Individuals should be prepared to pay something for their adult learning’.

References

Alsop, R., Bertelsen, M., & Holland, J. (2006). Empowerment in Practice. From Analysis to Implementation. World Bank.

Bagnall, R. G., & Hodge, S. (2018). Contemporary Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning: An Epistemological Analysis. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 13–34). Palgrave Macmillan.

Baily, S. (2011). Speaking Up: Contextualizing Women’s Voices and Gatekeepers’ Reactions in Promoting Women’s Empowerment in Rural India. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6(1), 107–118.

Batliwala, S. (1994). The Meaning of Women’s Empowerment: New Concepts from Action. In G. Sen, A. Germain, & L. C. Chen (Eds.), Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights (pp. 127–138). Harvard University Press.

Batliwala, S. (2010). Taking the Power Out of Empowerment–An Experiential Account. In A. Cornwall & D. Eade (Eds.), Deconstructing Development Discourse, Buzzwords and Fuzzwords (pp. 111–122). Oxfam GB.

Bauman, Z. (1997). Universities: Old, New and Different. In A. Smith & F. Webster (Eds.), The Postmodern University? Contested Visions of Higher Education in Society (pp. 17–26). SRHE and Open University Press.

Bauman, Z. (2002). A sociological Theory of Postmodernity. In C. Calhoum, J. Gerteis, J. Moody, S. Pfaff, & I. Virk (Eds.), Contemporary Sociological Theory (pp. 429–440). Blackwell Publishing.

Boyadjieva, P., & Ilieva-Trichkova, P. (2021). Adult Education as Empowerment: Re-imagining Lifelong Learning Through the Capability Approach, Recognition Theory and Common Goods Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan.

Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The Process of Empowerment: A Model for Use in Research and Practice. American Psychology, 65(7), 646–659.

Cruikshank, B. (1999). The Will to Empower. Democratic Citizens and Other Subjects. Cornell University Press.

DeJaeghere, J., & Lee, S. (2011). What Matters for Marginalized Girls and Boys in Bangladesh: A Capabilities Approach for Understanding Educational Well-Being and Empowerment. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6(1), 27–42.

Eurostat. (2010). Synthesis Quality Report: Adult Education Survey. European Commission.

Fleming, T. (2016). Reclaiming the Emancipatory Potential of Adult Education: Honneth’s Critical Theory and the Struggle for Recognition. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 7(1), 13–24.

Fleming, T., & Finnegan, F. (2014). Critical Theory and Non-traditional Students in Irish Higher Education. In F. Finnegan, B. Merrill, & C. Thunborg (Eds.), Student Voices on Inequalities in European Higher Education (pp. 51–62). Routledge.

Ibrahim, S., & Alkire, S. (2007). Agency and Empowerment: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators. Oxford Development Studies, 35(4), 379–403.

Loots, S., & Walker, M. (2015). Shaping a Gender Equality Policy in Higher Education: Which Human Capabilities Matter? Gender and Education, 27(4), 361–375.

Monkman, K. (2011). Introduction. Framing Gender, Education and Empowerment. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6(1), 1–13.

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Pruijt, H., & Yerkes, M. A. (2014). Empowerment as Contested Terrain. European Societies, 16(1), 48–67.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata (3rd ed.). Stata Press.

Robeyns, I. (2013). Capability Ethics. In H. LaFollette & I. Persson (Eds.), The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory (2nd ed., pp. 412–432). Blackwell Publishing.

Rocha, E. M. (1997). A Ladder of Empowerment. Journal of Planning Education & Research, 17, 31–44.

Roosmaa, E.-L., & Saar, E. (2012). Participation in Non-formal Learning in EU-15 and EU-8 Countries: Demand and Supply Side Factors. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 31(4), 477–501.

Rowlands, J. (1995). Empowerment Examined. Development in Practice, 5(2), 101–107.

Rubenson, K., & Desjardins, R. (2009). The Impact of Welfare State Regimes on Barriers to Participation in Adult Education: A Bounded Agency Model. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(3), 187–207.

Samman, E., & Santos, M. E. (2009). Agency and Empowerment: Review of Concepts, Indicators and Empirical Evidence (OPHI Research Chapter 10a). Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

Seddon, T. (2018). Adult Education and the ‘Learning’ Turn. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 111–131). Palgrave Macmillan.

Seeberg, V. (2011). Schooling, Jobbing, Marrying: What’s a Girl to Do to Make Life Better? Empowerment Capabilities of Girls at the Margins of Globalization in China. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6(1), 43–61.

Sen, A. (1985). Well-being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984. The Journal of Philosophy, 82(4), 169–221.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Allen Lane.

Stromquist, N. P. (1995). Theoretical and Practical Bases for Empowerment. In C. Medel Annonuevo (Ed.), Women, Education and Empowerment: Pathways Towards Autonomy (pp. 13–22). UNESCO-UIE.

Tett, L. (2018). Participation in Adult Literacy Programmes and Social Injustices. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 359–374). Palgrave Macmillan.

UNESCO. (2016). Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education 2015. UNESCO.

Unterhalter, E. (2019). Balancing Pessimism of the Intellect and Optimism of the Will: Some Reflections on the Capability Approach, Gender, Empowerment, and Education. In D. A. Clark, M. Biggeri, & A. Frediani (Eds.), The Capability Approach, Empowerment and Participation Concepts, Methods and Applications (pp. 75–99). Palgrave Macmillan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Boyadjieva, P., Ilieva-Trichkova, P. (2023). Adult Education as a Pathway to Empowerment: Challenges and Possibilities. In: Holford, J., Boyadjieva, P., Clancy, S., Hefler, G., Studená, I. (eds) Lifelong Learning, Young Adults and the Challenges of Disadvantage in Europe. Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14108-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14109-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)