Abstract

Workplace learning opportunities are closely linked to the type of job an individual has, and people’s use of available opportunities differs. Learning opportunities do not translate automatically into learning: individuals need to take advantage of them. This chapter presents a novel approach to investigating individual agency in workplace learning, studying early career employees in three sectors (Retail, Metals and Adult Education) across nine countries. It develops accounts of 71 workers’ learning across 17 organisations, thereby investigating workplace learning as embedded both in contexts of work and individuals’ wider life structures. When individuals’ agency in workplace learning is considered in isolation from its context, it cannot be properly explained; other areas of life add to and/or limit individuals’ learning opportunities. Employment interacts with other parts of life.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When considering workplace learning, a well-known reversible figure comes to mind. As with the duck-rabbit-illusion (Jastrow, 1899; Wittgenstein, 1958), we see the duck appearing, that is a given workplace with its features enhancing or limiting the opportunities for learning at work. An individual’s opportunities for workplace learning appear as defined by the way work is broken down into tasks and how much autonomy and discretion is assigned to the job holder. The latter implies that the workplace learning available depends on the ‘decent’ or ‘poor’ quality of one’s job: workplace learning thus seems determined by social structure.

Enter the rabbit. Learning opportunities do not automatically translate into learning: individuals also need to apply themselves to the opportunities on offer to make learning happen. Even in the same type of workplace, some individuals will make good use of the opportunities at hand, while others will not. More important, individuals’ behaviour has the potential to alter the workplace’s overall situation, as even alone they can push for more learning opportunities. Vice versa, an individual’s resistance to learning will alter the job at hand. In short, learning in the workplace appears as subject to individual agency.

To understand workplace learning, we cannot help but enter the long-standing debate about the interplay between social structure (the features of the workplace as embedded in the organisation and the wider social environment) and individual agency (as shaped by one’s overall life structure). Given that an employer’s interest takes priority in shaping workplaces, with individuals being required to accommodate (see Chap. 10), we cannot miss the conflict dimension present in workplace learning, with employers’ interests pitted against employees’ when it comes to shaping the workplace and its learning potential (see also Chap. 14).

Within the Enliven project, we have attempted to expand our understanding of both structure and agency. One strand of our work focuses on structure—how features of the workplace shape opportunities for learning at work. However, we have highlighted that structure mirrors previous organisational decisions: hence organisational agency (see Chap. 10). Our key interest had been to study the interplay between organisational and individual agency in workplace learning, taking account of the social conflicts involved.

The current chapter presents a novel approach to investigating the role of individual agency in workplace learning. We study individual agency of early career employees within the first 10 years of their careers. Employees are studied in three sectors (Retail, Metals and Adult Education) in the nine countries. Our approach allows us to study workplace learning as embedded both in the organisational context of the job and in an individual’s wider life structure. We developed accounts for 71 workers in 17 organisations, constructing between 3 and 8 individual learning biographies for each organisation.

As a result of the approach taken, we can compare differences between individual responses across largely similar workplaces offered by a single organisation. This means we can observe better how individuals apply themselves to opportunities for learning at work, as we have multiple observations reflecting similar ‘structural conditions’, yet can also observe different individual responses.

In this chapter, we introduce our approach before presenting three case vignettes referring to early career workers facing unfavourable conditions for workplace learning. However, in all three cases, individuals developed high levels of initiative to make learning happen despite dire conditions, and despite the fact that colleagues working in similar workplaces for similar organisations showed fewer efforts to overcome apparently similar structural barriers to learning. Details of the organisations and types of workplaces provided can be found in Chaps. 11, 12 and 13 (full accounts are available in Enliven Project Consortium, 2020a, b). Our aim is to further develop our approach to understanding the basis for what seems an outpouring of individual agency and its ability to trump structural constraints.

Our approach, explained in the next section of this chapter, starts with Emirbayer and Mische’s (1998) seminal understanding of individual agency. Next, we introduce Daniel Levinson’s conception of an urge for development inherent in an ‘always poorly balanced’ individual life structure, echoing his teacher Erik H. Erikson’s conceptualisation of ‘new tasks meet unfinished business’ as the driving force in adult development. For the application of the approaches, we need ‘thick descriptions’: a reconstruction of our research participants’ (learning) biographies, where we can observe their development over time and across areas of their overall life structure, such as education, gainful work, intimate relationships and family commitments, civic engagement and leisure time activities. To harvest data and organise them across areas of the life structure and time, we have developed an approach centring on summary graphic representations.

In the third section, we present three purposefully selected individual learning biographies, with research participants mastering considerably high levels of learning—within or outside work—despite fewer promising conditions in the workplace or resulting from their employment. All three learn ‘against all odds’, and we use their cases to demonstrate how individual agency can explore the more improbable opportunities at play. We use our reconstruction of the evolution of the life structure over time to understand better why the research participants claim good progress in workplace learning while colleagues in similar circumstances provide much less encouraging accounts. In the final section, we compare the cases and draw conclusions.

Understanding Individual Agency in Workplace Learning: A Life Structure Approach

How can we understand why some adults achieve learning at work while others do not, when the type of work done and the organisation offering the job are the same or very similar? There is a growing literature that answers this question by highlighting the significance for workplace learning of individual agency—understood as the individual capacity to act, to stimulate change by meaningful choices made—echoing the Weberian tradition (social action—soziales Handeln) (Bishop, 2017; Eteläpelto et al., 2014; Evans, 2017; Goller & Paloniemi, 2017, pp. 111–114).

What individuals actually do when they apply themselves in a situation and learn as a result—in short, when they use their agency—is perhaps captured best by Emirbayer and Mische’s (1998) seminal definition of agency (see Chap. 10):

Actors are always living simultaneously in the past, future, and present, and adjusting their various temporalities of their empirical existence to one another (and to their empirical circumstance) in more or less imaginative or reflective ways. They continuously engage patterns and repertoires from the past, project hypothetical pathways forward in time, and adjust their actions to the exigencies of emerging situations. … [A]ctors may switch, thereby changing their degrees of flexible, inventive, and critical response toward structuring contexts. (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998, p. 1012)

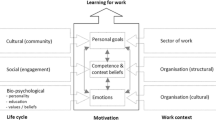

We agree that individuals navigate between their ways of making meaning of their pasts, their futures and their multiple present moments. Their lives populate various domains simultaneously: workplace, family, leisure, civic commitments and so forth. We understand agency as a capacity to relate competing claims of different domains and modes of time; that is by accommodating to one other the social domains in which an individual takes part and by relating to past, future and present. We therefore sought a framework which recognises this interplay between temporal modes; the life structure framework, developed by Daniel Levinson and colleagues in the 1970s for understanding adult development and learning over the life course, seemed particularly pertinent.

Levinson’s framework (see Hefler (2013) for a summary) echoed a rich field of research since the 1950s. The motivation to learn in adulthood was understood as an outcome of events in an individual’s life, both predictable (e.g. the timely death of parents) and unpredictable (e.g. an accident, military service in wartime, being laid off), and their inner world. Individuals need to find ways to adapt to change and strike new compromises between never diminishing needs and wishes. Levinson was, as we have seen, a student of Erikson, whose work had a huge influence on adult development theory in both North America and Europe.

Levison defines life structure as the object of analysis thus:

The life structure is the pattern or design of a person’s life, a meshing of self-in-world. Its primary components are one’s relationships: with self, other persons, groups, and institutions, with all aspects of the external world that have significance in one’s life. A person has relationships to work and to various elements of the occupational world; friendships and social networks, love relationships, including marriage and family; experiences of the body (health, illness, growth, decline); leisure, recreation, and use of solitude; memberships and roles in many social settings. Each relationship is like a thread in a tapestry: the meaning of a thread depends on its place in the total design. (Levinson, 1980, p. 278)

An individual life structure can therefore be captured by observing six areas: gainful work, intimate relationships, family (and care work), self-care (including topics of body, health, well-being but also religious activities), (organised) leisure activities and interaction with friends, and civil engagement and voluntary work.

Adults are expected to balance the demands and promises of all six areas in a satisfactory (or ‘good enough’) way: Time and again, as their environment changes, they need to intervene to rebalance their life structure. However, even when the ‘outer world’ works as individual hopes, the compromises required to hold everything together can become burdensome: dissatisfaction grows and motivates attempts to ‘change one’s life’; areas of life are re-arranged and a new balance sought.

A poor situation or break down in one area of life (e.g. no close friends, job loss, the breakup of an intimate relationship) burdens the life structure as whole and can make it precarious and unsustainable. A person may overcompensate for a void in one aspect of life by overly engaging in another. For example, being out of employment is stressful, given societal expectations and the dependence on wage income, but one may temporarily over-invest in another area. Early career workers may put their job first, exhausting themselves through long hours, at the cost of time for self-care and leisure with friends. This leads over time to growing imbalances in the life structure, perhaps requiring a sudden change—quitting ‘out of the blue’ is a possible scenario.

A poorly balanced life structure may be both the cause of developmental difficulties and a symptom of more severe psycho-social issues. Actively engaging in intimate relationships is considered an essential part of an individual life structure; the absence of initiative or good fortune with intimate relationships is expected to be experienced as overly stressful and limiting. To conclude, what takes place in one domain of life will spill over to other areas; the failure to fill vital gaps in one area will undercut the stability of the overall life structure, driving change even in areas, where—observed in isolation—everything seems fine. Actions which seem incomprehensible reveal their overall meaning when studied against the backdrop of the life structure.

Phases where individuals are open to engagement in serious developmental activities in an area of life can be considered ‘developmental windows’. They are often marked by changes in the balance of this life structure: former focal areas become less important, while others take centre stage. Many important life transitions (e.g. leaving the parental home, moving in with a partner, starting a family) demand temporary but significant shifts in the attention paid to various areas. To rework one life structure to fit with the needs of a new life stage, an individual needs to engage consciously or unconsciously in intense learning processes.

Tensions within the life structure are engines of change. The compromises required to achieve a fit between areas of the life structure are always unstable. Years of building up one life structure are followed by years where it is modified or disrupted. Adult development is understood as driven by the requirement to overcome the consequences of premature compromises made earlier.

On an objective level, life structures can be described by the outcomes of past achievements (or a lack of achievement). Levels of qualification attained or levels of occupational experience achieved are good examples of achievement and may last for considerable stretches of time. Having a stable place of one’s own to live might be another. Individuals may, of course, be simply endowed with resources for which they did not have to work. So on top of their own achievements, the life structure is strongly affected by resources provided (or taken away) by other people. In addition to past achievements, individuals also may be confronted in their current life structures with overcoming the negative consequences of previous situations, such as financial debt or weakened health.

We have therefore developed graphical representations of the content of the two interviews implemented with each early career worker. We include information on the domains of the life structure (gainful work, intimate relations, family, self-care, organised leisure, civic engagement) as well as participation in organised learning (formal or non-formal education). We also recorded whether organised learning had been supported by public funds or other mechanisms. Moreover, we observed the evolution of the life structure from the late phase of compulsory schooling (early teens) to the time of the interview and asked for their vision of the future, chiefly in relation to gainful work and further education. In the next sections, we give details and examples of the approach.

Learning Against All Odds: Understanding Resources for Individual Agency Embedded in the Individual Life Structure

In this section, we present three sketches of the learning biographies of early career workers. All faced conditions unfavourable to rich workplace learning or unstable employment: these suggest that their motivation to learn in the workplace or in general would be limited. However, in all three cases, they managed to stay motivated and to achieve considerable learning against the odds. These three case vignettes—all female—are taken from the three sectors studied and three rather different societal environments (Denmark, Bulgaria and Austria). They are summarised in Table 15.1.

Compensating for Poor Workplace Learning: Solveig in Danish Retail Work

In this case vignette, we study how wider life structure can provide the impulse for new plans to learn when the workplace offers practically no learning and very little motivation to seek opportunities to learn outside work.

Solveig (aged 20–24) was employed as a fresh food sales assistant in the food department of a large retail chain store (DK1 see Chap. 11). She had an apprentice contract for three and a half years and worked full-time (37 hours per week). Solveig was responsible for dressing and trimming the shop with fresh food and frozen products. She had just started her job in the organisation at the time of the first interview, with three years and three months left on her apprentice contract (Fig. 15.1).

Learning Biography Vignette: Solveig, a fresh food sales assistant in the food department in a store of a large retail chain in Denmark. (Source: (Enliven, 2020b, p. 99))

Solveig’s educational and career pathways seem close to the ideal type of non-linear trajectory: frequent changes in paths taken, difficulty in sticking to any decisions made (as she emphasised several times throughout both interviews). She completed the Danish lower secondary school system with a 10th grade diploma followed by enrolment as an industrial painter in an upper vocational educational programme (four and a half years). During that period, she moved into her own apartment, a so-called youth study apartment available to all young people in formal education. While attending lower secondary education and later the early phase of her painter training, she earned money as a student worker in a smaller retail supermarket and at a petrol station kiosk.

However, at a rather late stage, Solveig lost all motivation and dropped out of the industrial painting programme. She could not see herself becoming an industrial painter after becoming fully aware of what painters actually have to do. In order not to lose her student apartment, she needed to enter an alternative programme immediately; she therefore entered the retail programme, having found the opening for an apprentice on the web page of the company (DK1).

Solveig’s quick return to education was informed by her experiences of working in retail. She said she enjoyed interacting with clients and so was fine with the decision to enter a retail programme; however, the latter was prompted mainly by the need for any education in order not to lose the independence of living in a student apartment.

At the time of the first interview, Solveig’s day-to-day work was repetitive, routinised and with no learning requirements, other than to become acquainted with sheer boredom. Solveig performed the same tasks every day of the week with almost no variation. Customers asking for her assistance in finding an item represented a welcome diversion. New rules for displaying different products brought a kind of variation, at least for a brief period. Non-routine activities were entirely absent, despite her being on an apprenticeship track and not working as an unskilled helper. Surprisingly, Solveig rated her retail job as nevertheless more varied than her former experience of training to be an industrial painter.

By that time, Solveig was also confident that she might move on to work with a broader range of responsibilities within her employer’s organisation in the course of the programme. Indeed, by the time of the second interview, Solveig had changed departments, working in the dairy products unit. However, the nature of work had not changed at all: where she had previously placed fresh food, now she placed dairy products.

New tasks seldom required any complexity. Solveig illustrated this by describing new requirements for changing the price markings on frozen goods. This demanded some trial and error, but after a couple of attempts, she had fully absorbed this skill. Solveig mentioned only one area of personal development—how to handle difficult customers who became angry when unable to find the right items immediately. Over the months, she became more patient and relaxed with such clients.

Solveig described feeling stuck, bored and learning nothing at work. The lack of variation and challenges in her day-to-day work undermined her motivation, so she had difficulty getting out of bed in time. She explained that she had pressed for a change several times, but found herself rewarded with mundane tasks such as cleaning up the waste room. Moreover, she felt embarrassed by her inability to become used to her routine job, as though she were being unreasonable by asking for more variation and opportunities for learning.

Being asked about her future career plans, by the time of the first interview, Solveig reported the dream of running her own small shop, thereby reflecting that she did not foresee any managerial career pathway with her current employer. For the time being, the job’s main function was to provide income and her student flat. Roughly half a year later, life events unrelated to her job had changed her career ambitions (see below), with her apprenticeship in retail to be completed only to avoid her again becoming a ‘drop-out’.

The ambivalent significance of Solveig’s workplace experience became visible only in the light of her overall development in young adulthood. Neither the job itself nor the education programme but rather the attached right to student housing propelled her, allowing Solveig to move out of her parents’ home and become her ‘own woman’, entitled to make her own decisions.

Solveig revealed very little about her family of origin but reported that her father did not support her decision to enter the vocational stream and that she constantly felt under pressure from her family for her non-prestigious choices. While she had difficulties maintaining her interest in the jobs she selected, she defended the level of autonomy she gained from Denmark’s public support for apprentices. Through the money earned and the flat provided, she could live a self-determined life and invest in an intimate relationship comparatively early in life.

In a firm desire to defend this autonomy, Solveig learnt to survive the frustration involved in her current job. The latter took its toll. When she came home after a one-hour commute, she was too exhausted to do anything but watch TV and fall asleep, disrupting her previous spare time activities such as going to the gym regularly.

Solveig’s life structure and development became focused on developing her intimate relationship, the latter becoming even more important between the first and second interview. Her boyfriend got into trouble with the law and was convicted and imprisoned. She emphasised that her boyfriend’s trial had been a driver for her personal growth, changing her attitudes and perception of life as a whole and requiring her to immediately accept a much higher level of responsibility. Always considering herself a fighter, she focused on dealing with a very challenging situation where she could make a difference. Visiting her boyfriend in a distant prison became a key element of her life, leaving little space for anything else beyond work.

Having to give her relationship priority in this way, set Solveig’s overall life structure in motion again. Her undesirable current job became a firm basis from which she could care for her imprisoned boyfriend. Witnessing the wheels of justice working fuelled her desire to overcome her own marginal position, resulting in a (vague) plan to seek training later as a legal office assistant. She envisaged taking this step only after completing her current apprenticeship, which for the time being she accepted as providing necessary stability in her life situation. While her workplace learning remained limited, Solveig’s overall life structure allowed her to explore her agency and to seek meaningful learning and individual development. Public support provided for young adults in education plays an undeniable role in creating a base for learning and development against the odds.

Overcoming Limited Workplace Learning: Snejana in the Bulgarian Metal Sector

In our next example, the rather limited day-to-day informal learning opportunities of a semi-skilled blue-collar job are outweighed by the potential for new opportunities within a rapidly growing enterprise, offering stable employment and above-average pay, and allowing for supporting a family and down-payments on a home.

Snejana (30–34) operated a latheFootnote 1 in a milling-machine unit in a medium-sized company (BG 1—see Chap. 12 for details) in Southwest Bulgaria. The company, established at the beginning of the 1990s, has about 200 employees and specialises in small-batch production for larger metal companies.

The semi-skilled position Snejana held required only a few weeks’ introductory training and did not match her education. She completed her secondary education at a vocational high school in her hometown, giving her an accounting qualification. Afterwards, she left her parents’ home, moving to a nearby city, where she still lives. There she entered a higher education teacher education programme and received a bachelor’s diploma in the pedagogy of mathematics and informatics.

Although over-qualified for the job, Snejana emphasised that her previous education was of some help (Fig. 15.2):

I would not go so far as to say there is a match [between the completed education and the position she holds] but [the programmes] are of some use to me, because in university, I studied all kinds of mathematics and here, when we start calculating the points on the drawings as the programme is designed, it helps that I know how to calculate them. Because there are degrees, subtraction, addition, triangles. (BG1_ECW1_1_61)

Learning Biography Vignette: Snejana, a lathe operator in a Bulgarian local company in manufacturing metal products. (Source: Enliven, 2020b, p. 96)

During her university studies, Snejana’s parents assisted her financially. Nevertheless, she held various student jobs, as there was no public funding scheme to help. After graduation, she worked in a clothing workshop in the position of technical control of packaging for two years. Immediately after, she was on maternity leave for two years, taking her current job after that.

As it had a good reputation, Snejana had wished to work for her current company for some time before she found a job there:

There was no advertisement. I said that I wanted to submit my documents to eventually compete for a job and they told me to leave my CV and all else that was required and to wait, in case they might call me…. I submitted my documents every year… approximately after the fourth or third time when I submitted my documents, they called to say I could come. (BG1_ECW1_1_83)

The wages offered were above average, with even semi-skilled work paid higher than entrance-level jobs in secondary-level teaching. Moreover, the firm had responded to a local shortage of skilled labour by recruiting female talent, providing women with access to traditionally male blue-collar jobs.

Snejana operated a milling machine run by central programming (RCP). She had held this position since she was appointed. When entering the firm, she passed a course of theoretical training: ‘… the engineers, the head of the workshop also, the people in higher positions than us, were reading something like lectures to us, in order to familiarize us with the measuring equipment, the kinds of materials, the kinds of instruments’ (BG1_ECW1_1_96). This was followed by on-the-job training: ‘For two months I was with another person on a machine, after that they let me work independently with a machine’ (BG1_ECW1_1_109). Later, Snejana started work as a trainer at the company’s learning centre, supporting the practical training of newly appointed workers, in addition to working in the milling machine unit.

For her daily tasks, Snejana received information from the engineers on a memory stick, which she attached to the machine; she also had to write small programs herself, which broke up the otherwise highly routinised work. About 23 people worked in the milling machine unit, 17 of whom worked on RCP machines; the rest used a universal milling machine. When problems arise, the workers turn to the person in charge of the unit; if he cannot decide what is to be done, the case is referred to the head of the workshop or the chief engineer. Snejana’s position required teamwork:

We always work as a team with the engineers, with the person responsible for our unit. We make the decisions together in order to achieve the best possible result… From the highest level, from the engineer in chief, he tells us how to start, he distributes the things and after that, gradually, stage by stage, we come to what I am supposed to do. (BG1_ECW1_1_129)

Snejana found the working atmosphere in the company friendly:

The team is very united, we are all approximately the same age, we—on RCP are [young people], while on the universal milling machines, there older employees very often work… Personally, I am very pleased to have been put in that place. Some [colleagues] who you feel to be close friends, you see after work too. (BG1_ECW1_1_146)

She felt part of the company and had developed a feeling of organisational membership.

Snejana found her role as a trainer in the company’s learning centre challenging:

it is harder to be a trainer than a trainee. Because everybody has some ideas of their own, because you do not only need to know things here technologically but to understand what the machine will do at every moment. The programme and the machine—the similarity, to grasp the connection between the two and you must observe everything very carefully, especially when you start something new for the first time. Something new, when it is the first item after setting the machine, everything should be observed very carefully. (BG1_ECW1_1_216)

Snejana liked the company very much. Although educationally mismatched, she seemed to have found a place where she could apply herself and use her potential, quickly growing into the more demanding role offered in the evolving internal training centre. In the absence of a formalised career pattern, Snejana could hope to make progress based on her own specific contributions and become less constrained by the routinised nature of the work on one particular machine. This bright outlook drove her learning behaviour at work and helped her overcome the limited inspiration provided.

Snejana had grown up in a small town; her mother graduated from a mathematics high school; her father was an electrician. Going to university was her own choice and represented upward educational mobility for Snejana. Her childhood dream was to be a mathematics teacher. She found that she used mathematics extensively in her job: she found satisfaction in training new employees in the company, which enabled her to adopt a teacher’s role alongside her semi-skilled work. Outside work, however, Snejana had little time to attend further education beyond taking driving lessons at her own expense.

In terms of adult development, Snejana had mastered well all five markers of adulthood: finishing initial education, finding a job (with a living wage), leaving the parental home, entering into a civil marriage (nearly 12 years before the interview) and parenting two children. She had divorced her husband when her second child reached kindergarten age and, at the time of the interview, lived independently with her children in a home of her own, for which she was still paying instalments. The steady income from her job allowed her to live unsupported after the divorce. Overall, her life structure seemed quite stretched between responsibility as a mother (without a partner) and gainful work.

Snejana’s current job was a stronghold in her life structure. Thanks to it she could live independently and take care of her children. The price which she paid was no time for leisure activities and no space for personal development activities such as continuing and further education.

Rich Day-to-Day Learning in Insecure Employment: Nesrin in Austrian Adult Learning

In our third example, rich opportunities for day-to-day workplace learning were eagerly used despite high levels of job insecurity and comparatively low pay.

Nesrin (30–34) has been working as a teacher in adult basic education in a major provider organisation in Vienna for 14 months at the time of the first interview (see Chap. 13 for details on AT1). She had been born in Vienna as the third child of immigrant parents from Turkey. After compulsory schooling, she attended a three-year business VET school in Vienna but dropped out in the final year and started work in accounting. She did not enjoy it and, after some brief jobs, settled down in a travel agency, where she enjoyed herself with a range of interesting tasks. However, her employer went bankrupt during Nesrin’s first maternity leave; she got another job in a hotel, which she also liked. When the hotel ran into economic problems, she was made redundant, and during the following phase, she could find only short-time or marginal employment. After her second child was born, she could not find a job in tourism that provided working hours compatible with childcare; she therefore stayed at home but engaged in a range of further education classes in order not to lose skills (e.g. business English classes) and to enhance her employment prospects (e.g. office administrator adult apprenticeship).

Nesrin was desperately searching for a new job when a friend suggested training to become a tutor in German as a second language. Nesrin was convinced she did not have the necessary qualifications to enter the programme:

There I was, and I remember the first day: everyone introduces themselves, everyone tells us where they work and what kind of training and great things they do. Well, then it was my turn (laughs) and I said: I have not gone to university, I do not even know if I’m right in this class (laughs). (AT1_ECW4_1_131)

As it turned out, despite her unusual background, she overcame all doubts and succeeded very well in the training (Fig. 15.3):

you have to do a presentation right away and there is immediately this nervousness and this shame and this fear to take centre stage—you have to get rid of that … I have apparently made it and I constantly received so much positive feedback, … Yes, I am glad that I didn’t run away, because it got very close to me getting up and saying: I’m sorry, but I’m wrong here now. (AT1_ECW4_1_137)

Learning Biography Vignette: Nesrin, a teacher of adult basic education in an Austrian adult education centre. (Source: Enliven, 2020b, p. 92)

When she applied for an internship, Nesrin was immediately offered a position as an adult basic education teacher—a recent surge in funding had created a shortage in teachers in the field. When starting her job, she lacked the required credentials, but she acquired them via weekend courses during her first year in the job. At the time of the first interview, Nesrin taught 18 hours a week, plus another course of the same type as a substitute teacher for a second provider under the same funding scheme. At the time of the second interview, her weekly working hours had increased to 29.

Nesrin’s first class meant jumping in at the deep end. She was asked to take over a course after another teacher had left mid-term. The course was for migrant women with childcare obligations but limited German. Courses were held in local primary schools. Childcare for small children was provided free during classroom hours. This meant Nesrin worked mainly on her own and had limited contact with other adult educators.

She described a steady ongoing learning process in her day-to-day work. At the start, doing practically everything for the first time, she often needed to improvise. ‘So, I really had a tough time, muddling through all these challenges at once, there I had my learning by doing. Nothing, no educational programme, had prepared me for that’ (AT1_ECW4_1_903). She needed to overinvest in preparation during this crucial early phase.

Nesrin’s students were mainly refugees from Syria and Afghanistan and responding to traumatic experiences turned into a particular field of individual learning. She needed to adapt her plans for a lesson to make space for students’ immediate concerns:

Something unforeseen, let’s see …—Sometimes, when I am entering the classroom, I find one of my participants in tears. So, you simply cannot ignore her and continue as if nothing has happened. So, we stick together and we weep and mourn together …, you know, there are really moving issues at play. (AT1_ECW4_1_766)

She began to anticipate the need for exchange by reserving 30 minutes, out of 3 hours’ teaching, for any topic of this kind.

Nesrin also helped her students with administrative tasks, appointments with officials, and the like, in her free time, and long after they finished their courses. She explained her commitment as the outpouring of her personality as a born care giver. Although the course participants’ demands on Nesrin in her spare time were burdensome, she found confirmation in being needed:

It would be much better for me, something of a relief, if I could stop that, if I didn’t take everything so seriously; …—but that is, that is simply in my nature. That was already the case long before I started teaching, that I—I take after my mother. (AT1_ECW4_1_659)

Although she had never envisaged herself as a trainer, Nesrin enjoyed her new role. She knew from scratch that she had a great deal to learn in order to live up to what the job required, but felt excited by its challenges:

Somehow, I have ended up here—turned out it has been a great thing that I have ended up here—today, I would like to do nothing else, I am looking forward to working here until I retire, no joke, or even longer. (AT1_ECW4_2_1057)

Nesrin’s strong identification with her occupational role, and with her employer, energised her day-to-day workplace learning and helped her to live up to the job’s high demands in her early months.

Nesrin always strived for pleasure and meaning in a job. Many of her customer-facing roles and communicative tasks, such as working in a hostel with young casual guests in her early 20s, had provided these, enabling her to connect in personal ways. She always felt limited in her career options due to her interrupted education but took the initiative to improve her qualifications by completing the adult apprenticeship programme. Unfortunately, she then realised that her career options were limited by her obligations as a mother of two. This phase of uncertainty, during which she lacked a clear perspective, lasted for several years and resulted in a level of desperation, until a friend’s advice led to the chain of events and eventually—as described above—to her current job.

In retrospect, Nesrin accepted all these struggles as necessary: ‘And I just believe in kismet, right? Apparently, I had to wait for a reason, you know? … I had hard times to go through, but if it, if that was the reason, then it is good as it is’ (AT1_ECW4_2_1190). Despite the uncertainty of continuous employment, Nesrin was passionate about her new job and enmeshed herself fully in day-to-day learning, taking on any challenges offered.

Nesrin’s life structure was characterised by tensions between accepting the expectations of her conservative Muslim immigrant milieu and her own desires. She grew up in Vienna with three siblings. Her parents grew up in the same village in Turkey and migrated to Austria independently as adolescents, finally marrying. Nesrin’s father was a blue-collar worker; her mother worked as a housekeeper in a public care facility. Nesrin’s choice of education in a particular type of business VET school at the age of 15 is very common for girls in parts of Vienna’s Turkish community, and she felt it natural to get married and have a child around the age of 20. Although Nesrin could have been content with fulfilling the role of being a mother and wife, perhaps with some part-time work, she strived for more, making use of the training offered by the Austrian public employment service during a longer period of unemployment.

While Nesrin could count on the support of female members of her extended family, due to shift work at unsocial hours, her husband was hardly present during weekdays. All in all, Nesrin had to meet both her family’s and her job’s requirements mainly alone. Nevertheless, she found her position mainly a long sought-after enrichment, rather than a burden:

I don’t want to change anything; I want everything to stay as it is. It should continue the same way. Even when I really work a lot giving three courses, I also have to do a lot at home, but I always make my arrangements, …, that I neither neglect the kids, nor myself, nor, I don’t know—of course it happens, yes—sometimes I forget appointments [laughs]. (AT1_ECW4_2_334)

Discussion and Conclusions

The interviews with early career workers confirm that workplaces offering rich learning opportunities motivate these workers to enmesh themselves in workplace learning. In rich learning environments, these workers often engage fully in informal learning to develop their skills and work towards membership of their organisation and/or their occupations and professions. However, even when their workplaces are not learning-conducive, many early career workers report ways of learning at work.

In organisations dominated by restrictive learning opportunities, such as the retail examples in this project, cases stand out where interviewees held management trainee positions offering good learning opportunities per se, and their individual narratives were of commitment and will to develop. Against an overall expectation of ‘boring’ or monotonous retail jobs, burdensome for an individual’s personal development, some interviewees shared a different experience where simple jobs fitted quite well into their overall life structure for a period, for example, when bridging a gap until a new phase of education began, or merely acting as a temporary solution in an otherwise challenging life situation.

In retail, the research also revealed exceptional narratives of how interviewees succeeded in overcoming obstacles to learning that arose from the design of their workplaces—making learning happen against all odds. In adverse conditions, they were highly active in developing themselves and their professional identities. One way they described of making their tasks more comprehensive, and thus giving themselves new learning opportunities, was by making targeted demands on their superiors. Other interviewees described how they sought and used every informal opportunity in their daily work to achieve the same levels of skills as more experienced colleagues appeared to have. Such unexpected high levels of agency in restricted environments are often linked to overqualification in the current job, with young adults—for differing reasons—considering the job a ‘good enough’ solution for the moment. Though ‘stuck’ in a learning-restrictive work environment, they remain agentic, embracing all learning opportunities, sometimes making use of learning habits acquired earlier.

Clearly defined development pathways, commonly described as promoting learning, were observed in the machinery sector. Gaining full membership of one of the Basque co-operatives, which has predetermined stages of development, proved to be a strong motivator for individual development and agency. This was supported by other environmental factors that promote learning, such as responsibility for problem-solving, non-routine activities and the organisation’s provision of extensive training opportunities. In the Bulgarian metals sector, a pattern observed was that individuals’ learning benefits from changes—sometimes only small—in work tasks, such as moving from a simple to a more advanced machine, or taking on additional work as an in-house trainer (allowing partial time away from routinised to more demanding work tasks).

Among the interviewees from the adult education sector, especially those working as teachers or trainers, descriptions of highly learning-conducive workplaces dominated—as we anticipated would be common in teaching professions. In the first years of their careers as teachers, individuals reported that they adapted to the need for high levels of day-to-day learning ‘to survive’. Teaching requires commitment. Many interviewees added that they expected that growing experience would ease their day-to-day work pressures: entering the field was a transitional phase. For self-employed trainers, the early career phase involves establishing themselves in the field and attaining job security and a stable income. During this phase, temporary privations in other areas of life may be accepted as a necessary cost.

Despite the participants’ youth, Enliven research interviews resulted in narratives of varied life paths and rich past experiences in all areas of life. A considerable proportion of young adults look back on non-linear education and career pathways, which may include interrupted, resumed and planned training as well as experience of work in different industries and jobs, both in their country of origin and abroad.

Different patterns could be distinguished in the interplay of learning at the workplace and in other areas of life. Not all of these are strongly linked to particular features of the sectors under consideration: characteristics of the life structure, such as having children or not, have a significant influence on all other parts of life. Cases where a high level of learning at work coincides with lively activities in other areas stand in contrast with cases where learning across all areas of life is possible only to a limited extent. Many of our interviewees fell into the first category, and a few into the second. By moving beyond descriptions of the current life situation to a view spanning the life course, it becomes clear that when few learning opportunities are reported at a particular point in time, a longer view may reveal other dynamics.

Cases in which high levels of activity in one area of life compensate for a standstill or obstacles in other areas were found in all three sectors. Again, constellations tend to recalibrate over time. People who interrupted their education and currently earn their living in a routine retail job, for example, described this as a transitional situation: it reduced speed and pressure in several areas of their lives, while they forged or implemented new educational plans. Such a job might be an important step towards gaining independence from one’s parents and thus freedom in choosing one’s next career steps.

Demanding life situations can increase one’s engagement in gainful work. An ongoing crisis or imbalance in another part of life may call for stabilising at least one part of the life structure—for example, when a close relative suffers from severe illness. But there are also cases where life events force individuals to concentrate their agency on solving those problems and to put their learning ambitions in gainful work ‘on hold’. We observed this in cases of divorce or childcare obligations: the resulting life changes claimed an interviewee’s full attention.

The examples above have shown that if we consider the interactions of an individual’s agency in workplace learning in isolation from their context, the level of agency in workplace learning cannot be adequately explained. By applying Levinson’s (1980) life structure framework, our research shows how different areas of life add to and/or limit an individual’s learning opportunities and their agency in learning. Gainful work is an integral part of an individual’s life structure and always interacts with activities and events in other parts of life: intimate relations, family, self-care, organised leisure and civic engagement.

Notes

- 1.

Edited version of the original learning biography vignette written by Ulrik Brandi for (Enliven, 2020b).

- 2.

This is an edited version of the original learning biography vignette written by Vassil Kirov (see Enliven (2020b)).

- 3.

A lathe is a machine for fabricating metal for manufacturing.

- 4.

Edited version of the original learning biography vignette written by Eva Steinheimer for Enliven (2020b).

References

Bishop, D. (2017). Affordance, Agency and Apprenticeship Learning: A Comparative Study of Small and Large Engineering Firms. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 22(1), 68–86.

Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What Is Agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023.

Enliven Project Consortium. (2020a). Cross-Sector and Cross-Country Comparative Report on Organisational Structuration of Early Careers - Comparative Report and Country Studies in Three Sectors. Enliven report D 5.1. https://h2020enliven.files.wordpress.com/2021/08/enliven-d5.1_final.pdf

Enliven Project Consortium. (2020b). Agency in Workplace Learning of Young Adults in Intersection with Their Evolving Life Structure. Enliven Report D 6.1. https://h2020enliven.files.wordpress.com/2021/07/enliven-d6.1_final-2.pdf

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2014). Identity and Agency in Professional Learning. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & H. Gruber (Eds.), International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-Based Learning (pp. 645–672). Springer Netherlands.

Evans, K. (2017). Bounded Agency in Professional Lives. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development (pp. 17–36). Springer.

Goller, M., & Paloniemi, S. (Eds.). (2017). Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development. Springer.

Hefler, G. (2013). Taking Steps - Formal Adult Education in Private and Organisational Life. Lit-Verlag.

Jastrow, J. (1899). The Mind’s Eye. Popular Science Monthly, 54, 299–312.

Levinson, D. J. (1980). Toward a Conception of the Adult Life Course. In N. J. Smelser & E. H. Erikson (Eds.), Themes of Work and Love in Adulthood (pp. 265–290). Harvard University Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1958). Philosophical Investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans. Second ed.). Basil Blackwell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hefler, G., Fedáková, D., Steinheimer, E., Studená, I., Wulz, J. (2023). Early Career Workers’ Agency in the Workplace: Learning and Beyond in Cross-Country Comparative Perspective. In: Holford, J., Boyadjieva, P., Clancy, S., Hefler, G., Studená, I. (eds) Lifelong Learning, Young Adults and the Challenges of Disadvantage in Europe. Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14108-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14109-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)