Abstract

The emergence of fake news has systematically challenged traditional media institutions as disinformation and misinformation are increasingly utilised in political attacks on social media. As in many countries, also in Finland, the emergence of current counter media sites is closely connected to the rise of the anti-immigration movement, and immigration policies and immigrants have been targets of the massive social media disinformation and misinformation campaigns. By employing a nationally representative survey (N = 3724) from Finland, this study investigates how three social-media-related concerns addressing misinformation and disinformation are explained by political party preferences, media trust, and immigration attitudes. We found that the supporters of the populist party, the Finns, had more critical views on freedom of expression and monitoring of hateful content on social media. Moreover, they were less concerned with the flow of fake news on social media. Based on mediation analysis, we found that trust in traditional media and attitudes on immigration are lowest among the supporters of the Finns, which also explained their different views on fake news, freedom of expression and hateful content monitoring. Even though the independent variables were highly inter-correlated, they also associated individually with social media users’ perceptions. We argue that the accumulation of negative immigration attitudes and low trust in the media is reflecting attitudes towards social media among the supporters of populist parties. The results underline the populist right-wing communication strategy, which questions the reliability of mainstream media, undermines professional journalism, criticises political correctness, and appeals to those who are most frustrated with mainstream media and critical towards immigration.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social media have brought many positive things to political life: they facilitate the expression of opinions, set a lower threshold for political participation, change internal logics of political movements, and expand people’s information resources (see Bennett & Segerberg, 2013). However, there is a darker side of online participation, as social media are known to facilitate the spread of misinformation, targeted attacks in the form of hate speech, affective polarisation, and political disagreement (Barnidge, 2017; Boutyline & Willer, 2017; Del Vicario et al., 2016; Keipi et al., 2017).

Hybrid is the best word to describe the twenty-first century media system. Information is consumed, circulated, and interacted with in many different public arenas by multiple actors’ agenda setters (Chadwick, 2013). This means that traditional elite-driven media news production has become challenged by horizontal online political communication actors, such as fake news sites (Hatakka, 2019). The spread of fake news has recently gained a great deal of attention in public discussion due to its highly partisan nature and growth in conjunction with the popularity of social media (Kahan, 2017; Van Bavel & Pereira, 2018). Internet-mediated communication and social media have also offered new information platforms for those political ideologies that are not covered by traditional media. As presented in a study from Sweden, recently anti-immigration and racist views have become prevalent in social media discussions and people spread this type of content either intentionally or without checking its reliability (Ekman, 2019). Therefore, social media companies have been accused of enabling the massive spread of problematic content. Some features of platform infrastructure, particularly their vague policies, decontextualised content moderation system, and the algorithmic content curation that promotes content that attracts reactions in users, are driving the circulation of problematic content (Ekman, 2019; Nikunen, 2018).

Misinformation has become so widespread in the online context that the World Economic Forum (2014; Del Vicario et al., 2016) has listed it as one of the main threats to society. Because the online social media environment lacks third-party filtering, fact-checking, or editorial judgement on news content (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017), users have direct access to all manner of information and peer networks that become primary sources of news content. When the number of relevant information sources decreases, speculation, rumours, and mistrust are likely to flourish (Sunstein & Vermeule, 2009). At worst, this may lead to reinforcement of confirmation biases, segregation, and polarisation at the expense of the quality of information (Del Vicario et al., 2016). Misinformation and other problematic content tend to spread quickly online, at a pace faster than accurate information, due to social media users preferring to share novel and emotionally triggering content, which they assume will interest their peers (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Affective factors play a large role in the circulation of misinformation and rumours; when they trigger feelings such as fear or anger, they are far more likely to be circulated (Sunstein & Vermeule, 2009).

As daily life continues to be mediated by social media, the links to political ideology become highly relevant in better understanding of how various population groups view information, trust, and expression. Whereas researchers have extensively examined the links between political ideology, fake news, and media trust in the United States, Finland provides a valuable contrast as a multiparty system in a mature information society. With this population-wide study, we provide a new viewpoint on people’s social media concerns through media trust, political ideology, and immigration attitudes.

This chapter investigates how three social-media-related concerns addressing misinformation and disinformation are explained by political party preferences, media trust, and immigration attitudes. We state two research questions:

-

1.

How is political party preference associated with social-media-related concerns?

-

2.

To what extent are media trust and immigration attitudes related to party differences when assessing attitudes towards social-media-related concerns?

The chapter is structured as follows: first, we introduce the specific characteristics of the changing media landscape, then second, we focus on the relationship between Finnish political parties and media. Finally, we present our empirical research design including data, methods, results, and discussion.

Hate Speech, Fake News, and Political Ideology

Online media have facilitated democracy and deliberative participation by providing new and accessible platforms for political discussion and information consumption (Papacharissi, 2004; Santana, 2014). However, an abundance of evidence shows that in the online context, the tone of discussions can quickly turn uncivil and aggressive. This has been explained by anonymity (Santana, 2014), the absence of face-to-face contact (Papacharissi, 2004), infrequent and indirect comments (Coe et al., 2014), or social media users’ more extensive and ideologically diverse networks compared to nonusers (Barnidge, 2017). Overall, hateful or disrespectful tones can weaken the quality of political discussion online, and, accordingly, harm democracy (Massaro & Stryker, 2012; Papacharissi, 2004).

The term fake news, which is generally used to denote fabricated news stories purporting to be accurate, surfaced in 2016 and was frequently used during the Brexit vote and the American presidential election. Unlike the term misinformation, fake news refers to false information, which is created and spread deliberately and disguised as credible news for political or financial gain (Shin & Thorson, 2017; Silverman, 2017; Vargo et al., 2017). The societal consequences of fake news and misinformation have not yet been extensively studied, but they may affect voting decisions and increase mistrust towards governments (Einstein & Glick, 2015; Weeks & Garrett, 2014). Fake news and partisan media seem to be focused on themes such as anti-immigration, international relations, and religion, which are also themes highlighted by populist parties. Along with their popularity, fake news sites also influence traditional media because they can push their topics into the broader news media (Vargo et al., 2017). For example, the most significant Finnish fake media actor MV-journal (currently UMV-journal) has focused mostly on spreading anti-immigration views. Similarly, to many other anti-immigration actors on social media, it circulates mainstream news about immigration with a focus on crime or other negative topics (Ekman, 2019).

In the contemporary public discussion about fake news and misinformation, tension between demands for freedom of speech and control of inappropriate content—such as hate speech—is ongoing. It can even be said that in the current political climate within Finland—the context of this study—the concept of “freedom of speech” has to some extent become politicised as it is often applied to justify sharp criticism on immigration or even racist slander. As noted by Pöyhtäri et al. (2013), the recent discussion around hate speech has been somewhat confusing because it mixes up illegal comments that are likely to lead to punishment, with mere inappropriate behaviour.

“Hate speech” is a broad term used to denote negative and harmful tones of discussion. However, the conception of what is hateful has remained highly controversial. In the United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action, hate speech is defined as:

any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor. (2019)

Notably, hate speech is typically aimed at silencing people, for instance, preventing professional journalists and experts from doing their work (Pöyhtäri et al., 2013). Given these definitions, hate speech presents a challenging dilemma in terms of what is acceptable under freedom of expression and what is not.

Current research has shown that populist parties benefit more from social media than other political actors (Zhuravskaya et al., 2019). For example, it is widely acknowledged that populist parties use social media and alternative information as a strategy to question mainstream policies by proposing politically charged alternatives instead of established ones (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). In the populist view, society is typically divided into two antagonistic groups (i.e. ordinary people and the elite), the first group being glorified and the second attacked (Ernst et al., 2019; Mény & Surel, 2002). According to Engesser et al. (2016), in addition to emphasising the sovereignty of the people and attacking elites, populist communication is characterised by ostracising “others” and invoking the “heartland”. Linked to this theme, populist party supporters have been shown to consider journalists as part of the liberal elite (Wodak, 2015).

Populist communication strategy seems to be particularly successful on social media: research shows that people tend to evaluate populist politicians as more authentic than traditional politicians (Enli & Rosenberg, 2018). Participatory media enables a close and direct connection with the audience, helps to tailor their message to the target group, and fosters feelings of belongingness (Ernst et al., 2017, 2019). Furthermore, Enli and Rosenberg (2018) argued that typical characteristics of populistic strategy (i.e. antielitism, spontaneity, and outspokenness) are also strategies that can be used for constructing authenticity. As such, social media are a valuable asset that helps to facilitate a populistic communication style.

When traditional media are critical towards populist politics, the countermedia are able to offer a public platform for sharing alternative or even fabricated information. Countermedia, often referred to as alternative media, have played a significant role in the mobilisation of anti-immigration movements and views of the right-wing populist party (i.e. the Finns Party [FP]) in Finland. The content on Finnish countermedia sites has proliferated, with the sites growing in popularity during the autumn 2015 immigration wave in Europe. In general, countermedia are not always committed to certain political ideologies, but their main aim is typically to make a clear distinction between the elite and the general population, while also opposing the agenda of this elite group (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

Freedom of expression online is a double-edged sword, because it enables new forms of free expression, but also fosters the sharing of content that may be inaccurate or even democratically damaging in terms of adding to harmful polarisation. Furthermore, political ideologies differ in how they relate to the spread of fake news on social media. During the 2016 election in the United States, 62% of adults looked to social media for their news (Gottfried & Shearer, 2016), and the most popular fake news stories were more widely shared on social media than the most popular mainstream news stories (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Silverman, 2017). In terms of the left–right spectrum in the United States, the most popular fake news stories tended to favour conservatives rather than liberals (Silverman, 2017). Some previous findings on people who share fake news confirm that very conservative and older users (over 65 years) are the most likely to spread content referred to as fake news on Facebook (Guess et al., 2019).

In the United States, trust in the mainstream media has continued to decline as accurate and fair reporting is called into question. The decline since 2015 has been particularly steep among Republicans (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). In general, perceived trust in media is connected to people’s media consumption patterns, so that those who experience less trust in media tend to have more diverse media consumption patterns and use alternative information sources (Jackob, 2010; Tsfati & Cappella, 2003).

Finnish Media System and Political Parties

Finland is an interesting case for studying questions of media trust, freedom of expression, and fake news for several reasons. First, in Finland, the role of government has been influential in media and news production. The national broadcast company Yleisradio has been dominant in news production, and consumers have not had many alternatives to it until recently. As such, the government has been able to affect the presenting of news topics and viewpoints to a relatively high degree.

Second, because broadcast media has been somewhat centralised and run by national companies in Finland, alternative and countermedia are a new phenomenon and the majority of people are still unfamiliar with them. For instance, the most famous Finnish countermedia site was established in 2014, whereas the US media landscape is more diverse than in Finland, with alternative media having existed since the 1960s.

Third, in a global comparison, Finnish people’s trust in government and institutional authorities has been generally strong (Kouvo, 2014; OECD, 2021). In comparison with the United States—where institutional trust is weaker and supervisory control of freedom of expression is not accepted—the demand for alternative, non-institutional media choices is weaker. However, as Bennett and Livingston (2018) argued, there has been a global breakdown of trust in democratic institutions of press and politics, which is likely to help explain the emergence of extensive misinformation. Many reports and polls (e.g. OECD, 2017) have confirmed this trend of decreasing confidence levels across Western countries during past years.

Drawing from Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) media system theory, the Finnish media system is classified as a democratic corporatist model, which is characterised by, for example, substantial professionalisation, institutionalised self-regulation and an active role of the state. Recent survey research from Finland confirms that people’s trust in established national broadcast news media is still high, whereas so-called countermedia is the least trusted (Sivonen & Saarinen, 2018). An international comparison of 36 countries by Reuters Digital Institute revealed that in Finland the proportion of those who trust in news and media organisations is similarly the largest (Newman et al., 2017). According to the same report, distrust in the media seems to be connected to perceived political bias, which is most prevalent in countries with high levels of political polarisation, such as the United States, Italy, and Hungary.

Furthermore, the Finnish multiparty system provides a different environment for political polarisation compared to the two-party system of the United States. In Finland, the emergence of current countermedia sites is closely connected to the rise of the anti-immigration movement. As Ylä-Anttila (2018) has stated, the Finnish right-wing countermedia combines “facts with fiction and rumors, sometimes intentionally blurring the lines or spreading outright lies, most often cherry-picking, coloring, and framing information to promote an anti-immigrant agenda”. Finnish countermedia does not necessarily disseminate fabricated stories but instead typically takes news stories from other media sources and reframes them to fit a more suitable agenda (Haasio et al., 2017). Typically, countermedia actors utilise material provided by their readers and in return, the readers share the content produced by anti-immigration websites through their own social media accounts (Ekman, 2019). As argued by Nielsen and Graves (2017), the popularity of fake news is only partly about fabricated news reports and much more about a profound discontent with the news media, including politics and media platforms. Using this strategy, countermedia actors exploit their readers’ distrust towards mainstream media, particularly regarding news that reports about immigration issues (Ekman, 2019).

Because challenging the political elite and mainstream media are an integral part of today’s populism, countermedia should be understood as offering alternative explanations that challenge the mainstream, providing political fuel for those seeking it (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). A recent study from Finland confirms that lack of trust in traditional media does play a role in the consumption of countermedia. According to Noppari et al. (2019), using a populist countermedia site is motivated by scepticism and frustration. Users typically reported deep distrust in society and expressed their discontent with discussion that dominates the public sphere, with them turning to countermedia to find alternative narratives (Noppari et al., 2019). Hence, there seems to be a connection between having a high distrust, negative attitudes towards immigration issues, and the use of alternative news outlets on social media.

The members and the supporters of the populist right-wing party (i.e. the Finns Party [FP]) are relatively confident about the countermedia, whereas they are less trusting of traditional news media as compared to other parties (Koivula, Saarinen & Koiranen, 2016; Sivonen & Saarinen, 2018). The supporters of the Finns party are also more critical towards immigration issues and are active on social media (Koiranen et al., 2020; Ylä-Anttila, 2020).

The liberal environmental party Green League (GL) has been the clearest contrast to the Finns Party. Green League members and supporters are highly confident in traditional media; whereas members of the four other parliamentary parties are fairly or reasonably confident in traditional mediaFootnote 1 (Koivula et al., 2016; Sivonen & Saarinen, 2018). The four other parties are the Social Democratic Party of Finland (SDP), the National Coalition Party (NCP), the Centre Party of Finland (CPF), and the Left Alliance (LA). Before the rise of the Finns Party in 2011, the right-wing NCP, the SDP, and the agrarian CPF were the biggest parties for more than three decades, leaving a significant mark on the Finnish political system. As these new parties—the Finns and the Green League—have diverged from the traditional left–right spectrum, the Left Alliance has also developed even more strongly from a traditional working-class party into a so-called new left party. Nowadays, the Left Alliance members and supporters are more likely to be highly educated, young, and women (Koivula, 2019).

Method

Participants

Our analyses are based on survey data that included 3724 respondents. The data were collected in a two-part process. We obtained 2452 responses during the first part which was distributed by mail to a simple random sample of 18- to 74-year-old Finnish speakers (8000 total), which amounted to a 31% response rate. The data were improved with 1254 volunteer respondents (also aged 18–74) from a nationally representative online panel that a market-research company administered.

Detailed information on the data suggested that the final sample generally represented Finnish citizens as a group, although the oldest users and women were slightly overrepresented (Sivonen et al., 2018). We handled the age and gender distribution bias by using a poststratification weighting to balance the sample’s distributions to correspond with the official population distribution of Finnish citizens according to Official Statistics of Finland (Sivonen et al., 2018).

Measures

We asked the respondents about their concerns and opinions on social media in terms of three topics: the spread of fake news, freedom of expression, and monitoring of discussion. They were asked to rate the statements using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree. Table 10.1 presents the initial statements with the response scale.

The descriptive information of response distribution indicates that measures are nonlinearly distributed and there are relatively few completely disagree responses. To have a meaningful number of observations for multivariable analyses, we recoded the variables into three categories by combining responses 1–2 into Category 1 labelled as Disagree and responses 4–5 into Category 3 labelled as Agree.

Our primary independent variable is a measure of political party preference (i.e. the political party that the respondents felt most closely matched their beliefs). In the analyses, we mainly focused on the six largest parties in the Finnish parliament. Due to a lack of data, the supporters of other parliamentary parties—the Swedish People’s Party, the Christian Democrats, and the Blue Reform—were grouped with other minor parties in the Other category. We also grouped those who did not prefer any party in the None category.

As for the second independent variable, we used trust in the traditional news media. The initial question was, “How trustworthy do you consider the following” with the scale ranging from 1 = not trustworthy at all to 5 = very trustworthy. We measured attitudes towards immigration with an item that asks respondents, “How do you relate to increasing immigration” with the scale being 0 = “Very negatively” to 10 = “Very positively”.

Controlling for the effect of sociodemographic variables, we used the respondents’ ages asked via an open-ended question in which the respondents reported their year of birth. We categorised the respondents into three educational classes. The categorisations and descriptive statistics of the applied independent variables are shown in Table 10.2.

Analysis Strategy

We began the analysis by assessing the association between political party preference and the dependent variables. Second, we evaluated whether media trust and immigration attitudes were associated with the dependent variables. Finally, we used decomposition analysis to estimate how media trust and immigration attitudes confound party differences.

Our multivariable method is a multinomial logistic regression analysis that was performed with Stata 16.1. We present the results as average marginal effects. In the decomposition analysis, the method developed by Karlson, Holm, and Breen (hereinafter KHB) was used to obtain the confounding effects of media trust robustly with the nonlinear dependent variables (Breen et al., 2013). We generally hold the supporters of the populist party (the FP) as a reference category. In this way, we were able to evaluate the extent to which supporting the traditional major parties or other parties was related to participants’ views of social-media-related questions, as compared to supporting the FP.

Results

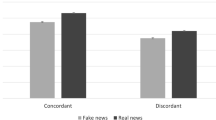

First, we analysed how political party preference is associated with respondents’ views on the spread of fake news, freedom of expression, and the monitoring of discussion in social media. The results of party differences are presented in Fig. 10.1.

As expected, political preference was associated with social media concerns: the supporters of the Finns Party especially stood out in the comparison as their views differ significantly from those of other parties’ supporters. The Finns Party supporters agreed the least with all three statements, which shows that they are most sceptical about freedom of expression in social media and least interested in monitoring discussions in social media due to hateful and attacking tendencies. In addition, they were the least worried about the spread of fake news. We also found that supporters of the Green League and the Left Alliance were most worried about fake news and, accordingly, most positive about content moderation on social media.

The first results of multinomial logistic models are presented in the columns in Table 10.3. Here, the average marginal effects describe the differences in the probability of obtaining a value of 3 (i.e. one agrees with the statement given). The results shown in the columns headed M1 indicates that supporters of other parties differ significantly from the supporters of the Finns Party, even taking into account the demographic background factors of the respondents.

Our next task was to assess how media trust and immigration attitudes were related to the dependent variables. First, we evaluated the direct associations of media trust and immigration attitudes with the party preference by adding the trust and immigration variables to the previously constructed models. The new models are presented the columns headed M2 in Table 10.3. Based on the analysis, media trust and immigration attitudes had a very strong association with all dependent variables.

The higher the media trust and the more positive immigration attitudes were the more likely one was to be concerned about the spread of fake news on social media. Similarly, those with high trust in traditional media and positive attitudes towards immigration were also likely to feel that users can freely express their opinions on social media. It also appeared that high trust in traditional media and positive immigration attitudes sharply increases the likelihood of the opinion that hateful and attacking discussions should be monitored on social media.

Finally, we confirmed how media trust and immigration attitudes contributed to the differences between the parties by using the KHB method. In this case, we decomposed the relationships between political party preference and the dependent variables according to trust in traditional news media and immigration attitudes. The results of the decomposition analysis are presented in Table 10.4. The indirect effects of political party preferences via media trust and immigration attitudes are presented as the logit coefficients. The indirect percentages display the proportions of both variables explained from the total effects of political party preferences on the dependent variables.

The results suggest that trust in traditional media and immigration attitudes significantly contributes to differences between the populists’ (i.e. FP) and other-party supporters’ views on the spread of fake news, freedom of opinion, and monitoring discussion on social media. In terms of the spread of fake news, media trust explained 15–26% of the differences between the FP and others. The confounding effect of immigration attitudes was even stronger, as it explained 20–28% of the party differences. However, it is noteworthy that party differences remained significant even after controlling for media trust and immigration attitudes.

When it comes to freedom of expression, the effect of media trust was very strong on party differences, as it explained 26.1–39.5% of the party differences. Immigration attitudes were also related to differences between parties, explaining 12–25% of them. The results showed that after taking into account the total effect of immigration attitudes and media trust, the supporters of FP would no longer differ statistically significantly from the supporters of LA.

Finally, trust in traditional media explained 21.6–32.3% of party differences when analysing respondents’ views on social media monitoring due to hateful and attacking tendencies. Here, we also found that immigration attitudes were related to the party supporters’ views by explaining 12–17.4% of party differences. The total effects showed that differences between parties remained significant even after considering the relatively high effect of media trust and immigration attitudes.

Discussion

The main goal of this chapter was to investigate how three social-media-related concerns addressing misinformation and disinformation are explained by political party preferences, media trust, and immigration attitudes. Furthermore, we considered how respondents’ demographic backgrounds associate with these concerns and whether media trust and immigration attitudes explain the party differences in views of social media concerns related to fake news, freedom of expression, and monitoring of social media discussion.

The results confirm that the supporters of the populist party, the FP, clearly stand out from other parties. They are particularly sceptical that social media enable freedom of expression and the least concerned about the spread of fake news. They were also strongly against monitoring social media discussions. Our findings underline that the supporters of populism are characterised by an active questioning of established media institutions.

Our results also suggest that media trust and immigration attitudes are highly related to social media concerns in a hybrid media context. First, we found that the higher the media trust and the more positive the attitudes towards immigration, the more likely one was to be concerned about the spread of fake news on social media, think that people can freely express their opinions on social media, and experience that hateful and attacking discussions should be monitored on social media.

According to the results of the decomposition analysis, low trust in traditional news media seems to be a significant explanator of why supporters of populism differ so prominently from others. We also found that attitudes on immigration are lowest among the supporters of the Finns, which was also related to their different views on fake news, freedom of expression, and hateful content monitoring.

Countermedia actors and populist politicians have systematically challenged traditional media institutions and offered media consumers new alternative media sites and narratives (Hatakka, 2019) which might have long-term effects on media trust. A similar media disruption tendency has recently been observed in all Western democracies (Bennett & Livingston, 2018). However, we need follow-up research on how the emergence of alternative media and systematic attacks on the prevailing media system are affecting trust in different media sources, and consequently people’s media consumption choices.

Our study naturally has its limitations. Because the concepts of fake news and hate speech are strongly politicised in current political debate and connected to ideological preferences, they are open to various interpretations, especially in self-reported survey research such as the present study. As some have suggested, perhaps the term fake news should be abandoned because it is so vague and used by politicians to attack news media and platform companies (Nielsen & Graves, 2017). Although “fake news” is frequently used instrumentally for political advantage, it has also become a useful concept for people in the expression of their frustration with the media environment, including misinformation, political propaganda, or poor journalism they frequently encounter, particularly in the online environment (Nielsen & Graves, 2017). We decided to use the term “fake news” instead of the more accurate equivalent “disinformation” in the survey because it is commonly used to denote all sorts of unreliable information in people’s everyday speech. However, we suggest that scholars should thoughtfully consider the context in which the term is applied when using it in surveys. During our data collection period, “fake news” was widely used in news media, particularly because of the Trump’s era, and the spread of fake news was considered as a new and alarming phenomenon in public discussion.

Our findings confirm that political communication on social media creates tensions because users’ conceptions of what is appropriate online behaviour vary greatly. Although social media promote deliberation and free expression of opinions, there is also public concern for the need to control some harmful forms of participation. As we have found, social media users possess contrasting views about hateful content and content moderation, which arise from their experienced trust in media, immigration attitudes and political preference. To balance these different views in a moderation strategy is a challenging task for social media providers. Because those who distrust traditional media are also strongly against content moderation, moderation of the views that they support might lead to even deeper frustration and alienation from traditional media.

Notes

- 1.

The Finnish parliament consists of nine parties. We do not have the survey data from the Christian Democrats, Movement Now and the Swedish people’s Party. These three parties are the smallest in the Finnish parliament.

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Barnidge, M. (2017). Exposure to political disagreement in social media versus face-to-face and anonymous online settings. Political Communication, 34(2), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1235639

Bennett, L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge University Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., & Holm, A. (2013). Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(2), 164–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113494572

Boutyline, A., & Willer, R. (2017). The social structure of political echo chambers: Variation in ideological homophily in online networks. Political Psychology, 38(3), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12337

Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12104

Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petronic, F., Scala, A., Caldarellia, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchia, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517441113

Einstein, K. L., & Glick, D. M. (2015). Do I think BLS data are BS? The consequences of conspiracy theories. Political Behavior, 37(3), 679–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9287-z

Ekman, M. (2019). Anti-immigration and racist discourse in social media. European Journal of Communication, 34(6), 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323119886151

Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2016). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society, 20, 1109–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

Enli, G., & Rosenberg, L. T. (2018). Trust in the age of social media: Populist politicians seem more authentic. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118764430

Ernst, N., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Blassnig, S., & Esser, F. (2017). Extreme parties and populism: An analysis of Facebook and Twitter across six countries. Information, Communication & Society, 20, 1347–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329333

Ernst, N., Blassnig, S., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., & Esser, F. (2019). Populists prefer social media over talk shows: An analysis of populist messages and stylistic elements across six countries. Social Media + Society, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118823358

Gottfried, J., & Shearer, E. (2016). News use across social media platforms 2016. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2016/05/26/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2016/

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau4586. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

Haasio, A., Ojaranta, A., & Mattila, M. (2017). Valheen lähteillä - Valemedian lähteistö ja sen luotettavuus. Media & Viestintä, 40(3–4), 100–121. https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.67796

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press.

Hatakka, J. (2019). Populism in the hybrid media system. Populist radical right online counterpublics interacting with journalism, party politics, and citizen activism (Doctoral thesis). University of Turku, Turku. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-7793-2

Jackob, N. G. E. (2010). No alternatives? The relationship between perceived media dependency, use of alternative information sources, and general trust in mass media. International Journal of Communication, 4, 18. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/615

Kahan, D. M. (2017). Misconceptions, misinformation, and the logic of identity-protective cognition. Kahan, Dan M., Misconceptions, Misinformation, and the Logic of Identity-Protective Cognition (May 24, 2017). Cultural Cognition Project Working Paper Series No. 164; Yale Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 605; Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 575. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2973067

Keipi, T., Näsi, M., Oksanen, A., & Räsänen, P. (2017). Online hate and harmful content: Cross-national perspectives. Routledge.

Koiranen, I., Koivula, A., Saarinen, A., & Keipi, T. (2020). Ideological motives, digital divides, and political polarization: How do political party preference and values correspond with the political use of social media?. Telematics and Informatics, 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101322

Koivula, A. (2019). The choice is yours but it is politically tinged. The social correlates of political party preferences in Finland (Doctoral thesis). University of Turku, Turku. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-7587-7

Koivula, A., Saarinen, A., & Koiranen, I. (2016). Yksipuolinen vai tasapuolinen media? Puoluejäsenten mielipiteet mediasta . Kanava, 8.

Kouvo, A. (2014). Luottamuksen lähteet. Vertaileva tutkimus yleistynyttä luottamusta synnyttävistä mekanismeista (Doctoral thesis). University of Turku, Turku. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-5715-6

Massaro, T. M., & Stryker, R. (2012). Freedom of speech, liberal democracy, and emerging evidence on civility and effective democratic engagement. Arizona Law Review, 375. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2042171

Mény, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002). The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 1–21). Palgrave Macmillan.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3026082

Nielsen, R. K., & Graves, L. (2017). ‘News you don’t believe’: Audience perspectives on fake news. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Report. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-10/Nielsen&Graves_factsheet_1710v3_FINAL_download.pdf

Nikunen, K. (2018). From irony to solidarity: Affective practice and social media activism. Studies of Transition States and Societies 10(2), 10–21. http://publications.tlu.ee/index.php/stss/article/view/655

Noppari, E., Hiltunen, I., & Ahva, L. (2019). User profiles for populist counter-media websites in Finland. Journal of Alternative and Community Media, 4(2019), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1386/JOACM_00041_1

OECD. (2017). Trust and public policy: How better governance can help rebuild public. Paris, France. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en

OECD. (2021). Drivers of trust in public institutions in Finland, OECD Publishing, Paris, France. https://doi.org/10.1787/52600c9e-en

Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444804041444

Pöyhtäri, R., Haara, P., & Raittila, P. (2013). Vihapuhe sananvapautta kaventamassa. Tampere University Press.

Santana, A. D. (2014). Virtuous or vitriolic. Journalism Practice, 8(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.813194

Shin, J., & Thorson, K. (2017). Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. Journal of Communication, 67(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12284

Silverman, C. (2017, February 26). What exactly is fake news? The Fake Newsletter. http://us2.campaign-archive.com/?u=657b595bbd3c63e045787f019&id=e0b2b9eaf0&e=30348b6327

Sivonen, J., Koivula, A., Saarinen, A., & Keipi, T. (2018). Research report on the Finland in the Digital Age-survey. University of Turku, Department of Social Research.

Sivonen, J., & Saarinen, A. (2018). Puolueiden kannattajien luottamus mediaan. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka, 83(3), 287–293. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2018112348908

Sunstein, C., & Vermeule, A. (2009). Conspiracy theories: Causes and cures. Journal of Political Philosophy, 17(2), 202–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2008.00325.x

Tsfati, Y., & Cappella, J. N. (2003). Do people watch what they do not trust? Exploring the association between news media skepticism and exposure. Communication Research, 30(5), 504–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203253371

United Nations (2019). United nations strategy and plan of action on hate speech. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/UN%20Strategy%20and%20Plan%20of%20Action%20on%20Hate%20Speech%2018%20June%20SYNOPSIS.pdf

Van Bavel, J. J., & Pereira, A. (2018). The partisan brain: An Identity-based model of political belief. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.004

Vargo, C. J., Guo, L., & Amazeen, M. A. (2017). The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014–2016. New Media & Society, 20(5), 2028–2049. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817712086

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Weeks, B. E., & Garrett, R. K. (2014). Electoral consequences of political rumors: Motivated reasoning, candidate rumors, and vote choice during the 2008 US presidential election. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 26(4), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edu005

Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear. Sage.

World Economic Forum. (2014). The rapid spread of misinformation online. http://reports.weforum.org/outlook-14/top-ten-trends-category-page/10-the-rapid-spread-of-misinformation-online/

Ylä-Anttila, T. (2018). Populist knowledge: ‘Post-truth’ repertoires of contesting epistemic authorities. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 5(4), 356–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2017.1414620

Ylä-Anttila, T. (2020). Social media and the emergence, establishment and transformation of the Right-Wing Populist Finns Party. Populism, 3(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1163/25888072-02021043

Zhuravskaya, E., Petrova, M., & Enikolopov, R. (2019). Political effects of the Internet and social media. Annual Review of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-081919-050239

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Malinen, S., Koivula, A., Keipi, T., Saarinen, A. (2023). Shedding Light on People’s Social Media Concerns Through Political Party Preference, Media Trust, and Immigration Attitudes. In: Conrad, M., Hálfdanarson, G., Michailidou, A., Galpin, C., Pyrhönen, N. (eds) Europe in the Age of Post-Truth Politics. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13694-8_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13694-8_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-13693-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-13694-8

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)