Abstract

This essay argues that shortcomings in our approaches to global agriculture and its data infrastructures are attributable in part to a constricted application of population concepts derived from biological sciences in the context of international development. Using Palestine as a case study, this chapter examines the category of baladi seeds as a community-generated characterization of population, and one which arguably defies reduction to data. Drawing on quantitative research on farmer participation in informal seed production for wheat in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt) and oral histories of farmers in the West Bank, this chapter analyzes the relation between participatory plant breeding initiatives, heritage narratives, and international agricultural research in rendering baladi seeds legible for archiving. It considers the multiple technological practices through which these institutions characterize and manage access to cultivated seeds, and how they differently approach problems of standardization, scalability, and variability. Through case studies of national and local seed saving initiatives, it asks, in turn, whether baladi seeds can be reduced to data, how they might be reduced to data, and whether they should be reduced to data.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fundamentally, data constructs a narrative around seeds, characterizing plants according to genetics, morphology, habitat, and a range of other factors. Yet people express numerous ways of living through seeds, in priorities and concepts imperfectly reduced by data schema. This chapter argues that shortcomings in our approaches to global agriculture and its data infrastructures are attributable in part to a constricted application of population concepts derived from biological sciences in the context of international development. Data infrastructures reflect the priorities of the institutions the produce them, as well as the social and political contexts in which those institutions operate. As a result, data mirror the inequalities and exclusions of the societies in which they are embedded. In historical terms, the imperial/colonial framework of plant science provided the categories from which twenty and twenty-first-century data infrastructures are derived. These infrastructures have simultaneously enabled and restricted our ability to imagine alternative agricultures. Towards exploring these alternatives, this paper explores how multiple institutions and communities of practice define the population as an object of conservation, research, and development.

As a fundamental object of data infrastructures, biodiversity has multiple genealogies. As a term, it is commonly used to encompass species, genes, and ecosystems. It was deployed in the 1970s by conservation biologists concerned with species extinction, but also, in agricultural research, by breeders concerned with securing access to global plant genetic material for improved varieties. Beloved by proponents of community sovereignty, the concept of biodiversity is nevertheless trafficked by national governments seeking rhetorical and political tools for control of territory and natural resources, which are documented as biological populations in need of protection. Institutions dedicated to international development inherit this muddle of values and priorities; and so it is little surprise that their databases reflect the complexity and confusion of historical approaches to biodiversity preservation.

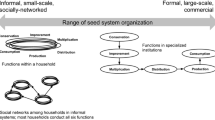

The concept of population applies to with cultivated plants quite differently than other flora and fauna, inasmuch as crops are human social and technological productions as well as natural objects. The diverse social and technological styles of agricultural production, and their variable relation to data concepts rooted in population biology, are the subject of this chapter. Within the field of agrobiodiversity preservation, data scientists often classify certain domains of research and production as “informal,” where informal is a synonym for community. This identification runs the risk of ignoring diverse local institutional approaches to agricultural practice, which take shape in the absence of, and in opposition to, formal networks of seed production, distribution, and conservation.

Using Palestine as a case study, this chapter examines the category of baladi seeds as a community-generated characterization of population, and one which arguably defies reduction to common databases. Through case studies of national and local seed saving initiatives, it asks, in turn, whether baladi can be reduced to data, how it might be reduced to data, and whether it should be reduced to data. It considers the multiple technological practices through which institutions characterize and manage access to cultivated seeds, and how these differently approach problems of standardization, scalability, and variability.

Ultimately, this paper identifies a series of social and political considerations that trouble efforts to harmonize data produced in the context of international development. It does not propose universal technical solutions to these problems, because it holds that social and political solutions must precede and direct technological ones. This is a sobering insistence from a place where conflict seems intractable, and where power is alternately sapped by occupation and a bloat of international development agencies complicit in neoliberal development strategies. Agrobiodiversity preservation in the West Bank takes shape against the backdrop of Israeli occupation, which hobbles commercial agricultural development and intensifies dependence on Israeli imports of seeds and finished agricultural products. There is a necessary and relentless focus on access to land and water, amplified by the occupation and the construction of the separation wall snaking the West Bank. Moreover, in a post-Oslo Palestine, local NGOs acquiesce to a multitude of donor priorities and fall in line with their inconsistently expressed requirements. The result is an overlapping array of projects in pursuit of community empowerment, national sovereignty, and neoliberal development. Palestine is an illuminating case study not in spite but because of these tendentious questions of occupation and marginalization, and the ways in which rhetorics of food security and food sovereignty face off or muddle together. These are the world’s problems, expressed pointedly in the extremity of the occupied West Bank.

2 “Population” as Unit of Analysis and a Target of Preservation

Ex situ gene banks remain the most prominent conservation strategy for cultivated crops and their wild relatives; but critics have charged that they are insufficient in multiple respects, severing the relation of plant genetic material not simply to its environs, but also to the farmers who have stewarded it. In response, agronomists and breeders have designed in in situ conservation strategies aiming to foster on-farm preservation. While both approaches to conservation have created spaces for sustainable agricultural improvement, they have often reified categories of “landrace” and “heirloom” that mark locally adapted seeds as stable artifacts of past agricultural practices, to be collected and preserved in static form. The concept of landrace presupposes a regional ecotype, locally adapted variety, or traditional variety of a domesticated species of plant or animal, generally distinguished by its isolation from other populations of the species. It is typically opposed to a cultivar, produced by selective breeding and maintained by propagation. Practice suggests a more fluid relation between on-farm and ex-situ improved varieties. The landrace concept has been called into question in part because of the hard line it draws between laboratory-based breeding and farmer selection (Berg, 2009). In addition, many “heirloom” seeds are a previous century’s commercial varieties, suggesting the ways in which agricultural knowledge is characterized by mobility rather than stasis, and transaction rather than withholding.

This muddle derives from the imperfect application of the population concept to diversity in cultivated plants. In the simplest terms, a population is “all coexisting individuals of the same species living in the same area at the same time.” The primacy of the population concept derives from a historical focus on species as the primary unit of analysis, beginning in the natural sciences of the eighteenth century. The species unit has remained fundamental to the twentieth-century disciplines of population genetics and community ecology, as well as their integration in the new population biology of the 1950s. These sciences of the “New Synthesis” were in turn prerequisite to the founding of conservation biology as a “science of crisis” in the 1970s, and subsequent attempts to mark populations for conservation and restoration (Simberloff, 1988; Soulé, 1985). In international agricultural research, population concepts derive from agronomy and conservation biology. Their primary orientation remains toward species protection, codified in the structure of gene banks according to Linnaean binomials. This static taxonomic practice, fundamental to historical plant database design, remains dominant in all formal agricultural research. These continuities obscure the fact that agriculture itself is one of the greatest disruptors of ecosystems. The large-scale farming of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have intensified this disruption. Even so, agricultural improvement relies on the introduction new genetic material well adapted to local conditions; and thus an imperative to preserve species richness is a focus of modern conservation policies.

Efforts to map species were aspects of a European imperial project to identify nature in an original state, and to justify colonial management of resource stocks (Davis, 2009, 2015; Drayton, 2000; Grove, 1995). The quest for useful plants provided the machinery of imperialism and colonization through European botanic gardens. Forged against fears of colonial degeneracy and the pursuit of valuable natural resources, these scientific projects provided the foundation for nineteenth and twentieth-century models of development rooted in concepts of social evolution and economic growth. In the wake of imperial collecting projects, European and American governments continued to sponsor extensive natural history expeditions (Anker, 2001; Pauly, 2007). The heirs of European botanic gardens oversaw the institutionalization of new sciences of the environment, with institutions such as the New York Botanic Garden incubating the discipline of ecology (Kingsland, 1995; Mitman, 1992). The coalescence of ecology as a discipline in the early twentieth century brought new attention to the study of how organisms live in their environments, and intensified the development of a “baseline concept” in conservation efforts (Alagona et al., 2012). The interwar period, in turn, saw the international development of mathematical models in population growth and dynamics, competition, and predation, inspiring new approaches to the study of biology and population genetics (Huneman, 2019).

By the 1940s, the biologist E.O. Wilson, Ronald Fisher, and others contributed the insights of population genetics to an institutional and intellectual movement ultimately celebrated as a new Darwinian synthesis. Population biologists of the 1950s linked the driving questions of community ecology and population genetics through theorizations of ecological niche and island biogeography, and, crucially, through the application of mathematical modeling to the history of life on earth. As with any synthesis, this one concealed divisions (Huneman, 2019; Kingsland, 1995). Inter and intra-disciplinary debates regarding the relative merits of experimental and laboratory work, theory and practice, and modeling vs. field study are not unique to population ecology; and, indeed, we see them echoed in contemporary discussions of the application of big data to a range of practices, including agriculture and agro-biodiversity. Mathematical models produced striking insights, and yet they seemed to bely the messiness, complexity, and fundamental uncertainty of the life they aimed to characterize. In the field, it is never so simple.

The new synthesis echoed the timelessness of Linnaean natural history rather than the changeability pursued by Charles Darwin and others (Huneman, 2019; Kingsland, 1995). That is: the twentieth century pursued the fixity of the 18th, in denial of the intervening century’s messy confrontation with evolution. Crucially, this confrontation was enacted not simply in the theory of natural selection, or in the social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer, but in the agricultural lands of the Maghreb, the Americas (including the American South), and the East Indies. These were the fields of Euro-American colonial expansion, converted for global commodity export. By the mid-twentieth century, they were the sites of agricultural modernization projects. By the 1970s, they were the hosts of a network of Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) centers for research on food security, rural poverty, and sustainable development.

CGIAR was founded against the backdrop of international agricultural modernization. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the US and Europe competed to establish themselves as dominant exporters of food, then of agricultural inputs, based on a model of input-intensive industrial agriculture. The export of high-yielding seeds and agricultural methods developed by American agronomists aimed to usher in a “Green Revolution,” averting the Red alternative of Communism by increasing rural prosperity. Global conservation strategies developed to match these agendas, oriented at first toward state control of natural resources, and then toward an international order that recognized the sovereignty of member states over others. Aiming to build on the alleged successes of the Green Revolution, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations supported programs of agricultural modernization and the free exchange of germplasm between countries for the use of breeders.

CGIAR’s mandates for food security and sustainable development included large-scale programs for agro-biodiversity preservation, the most notable of which was a network of international gene banks to amass landraces, and, later, wild relatives of target grains and legumes. When international agricultural research centers turned their attention to biodiversity loss, it was to argue that public and private breeders should have access to global plant genetic resources: moving seed stocks out of the field and into banks from which they could circulate to countries with the capital to pursue research (Curry, 2017; Fenzi & Bonneuil, 2016; Flitner, 2003; Fullilove, 2017; Saraiva, 2013). Today, international research organizations govern the free transfer of global germplasm through standard material transfer agreements (SMTAs) defined by the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources (2001). (The Middle East and North Africa is served by the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), headquartered in Syria until 2010, and now in Lebanon.)

Historical arguments for conservation are often nostalgic; and the past provides an imperfect guide to the future at best (Alagona et al., 2012; Cronon, 1992, 1993). In spite of the fashion for heritage seeds and landraces untainted by modern breeding methods, the quest for origins is in many ways misguided, masking the fluidity of agro-biodiversity. These shortcomings suggest the ways in which a focus on species fails to characterize biological diversity, within and beyond the practice of agriculture.

Moreover, arguably human beings have been under-theorized in most studies of populations, defined as ecosystems managers rather than objects of study. The application of entomologist Paul Ehrlich’s (1968) population studies to human beings and subsequent discussions of the planet’s “carrying capacity” are the exception that prove the rule. These alarmist scenarios of a global overpopulation crisis provided the basis for imperatives of yield that have governed international debates about “food security” from the post-World War II period to the present day.

Alternative approaches to preserving agro-biodiversity have the potential to elevate social and political considerations. Agroecological approaches favor a focus on ecosystem over species, toward polycultural models of production. Agroecological approaches have applied practices such as nutrient cycling and intercropping to modern agriculture, drawing on techniques developed over millennia of agricultural practice and applied by farmers across the world (Altieri, 1995). Intellectually, agroecologists are indebted to these millennia of farmers. More narrowly, the discipline draws on concepts of ecological succession and landscape formulated by community and population ecologists such as Frederic Clements and Henry Gleason. Since the 1980s, agroecological approaches have been popularized by agronomists such as Miguel Altieri not simply for their ecological aspects, but also for their social and political implications. These implications are made explicit by the global food sovereignty movement Via Campesina, which promotes agroecological methods as an expression of traditional peasant farming.

3 Baladi Seeds in Occupied Territory

In recent decades, international agricultural researchers have endeavored to include farmer knowledge in data infrastructures and plant breeding projects. Perhaps ironically, agrarian knowledge provides both the source and the target of their innovations. In Palestine, which provides the case study for this paper, collectors seek local varieties, drawing on the knowledge of local farmers to identify baladi seeds (literally “my country,” and connoting local and traditional production, native to place) (Nadar, 2018). In common usage, one could regard “baladi” as a synonym for local, and it connotes a similar array of associated, yet contested values: community, tradition, ownership, and stewardship, to cite a few examples. In a biological context, “baladi” refers generally to a population comprised of numerous heterogeneous lines with their own individual characteristics. In wheat, for example, characteristics might encompass resistance to drought, pests, and rusts, as well as traits related to gluten content and yield (Nadar, 2018). Collectors render baladi populations legible for archiving through morphological analysis, physical multiplication, and multiple documentation processes. Thus, even as it shelters and generalizes enormous diversity, the population remains the the object of preservation and the principal unit of analysis.

But baladi seeds are differently characterized in projects that seek to express community values of taste, appearance, and texture as primary. That is, baladi seeds may stabilize through other means than line characteristics, such as the stories woven around them. Overlapping oral, literary, and documentary practices do not, however, have the same status as data. That is, only certain markings are viable representations of agrarian knowledge in international research and development. The remainder of the essay explores some of these alternative characterizations of population through a survey of four institutions pursuing agro-biodiversity preservation projects in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt).

In spite of the challenges posed by climate change and occupation, Palestine has one of the highest concentrations of agrobiodiversity in the world, consisting of wild pulses, grains, woody plants, and trees that humans began to modify and domesticate about 12,000 years ago (Tesdell et al., 2020). It is a center of diversity for the crops of the Neolithic (wheat, barley, bitter vetch, chickpea, lentil, flax, and oat) as well as numerous legume species and tree crops (Tesdell et al., 2020; Zohary & Feinbrun-Dothan, 1966). In scientific terms, drylands such as Palestine’s are a focus of twenty-first-century breeding research because they host plants and crop varieties adapted to drought, salinity, and high temperatures. These qualities make them objects of interest in the face of global climate change. Seeds form the basis of new research into drought resistant wheat varieties, and through “pre-breeding” can introduce genetic material into parental germplasm used in the production of new seed varieties (e.g. Buerstmayr et al., 2012).

Agricultural science in Palestine took shape against the background of European colonial policy after World War I, Israeli national development after World War II, and Israeli occupation of the West Bank after 1967. Each facilitated governance by circumscribing and cataloguing practices of cultivation in the language of Euro-American agricultural science (Tesdell, 2013). In the early decades of the twentieth century, international wheat breeding initiatives, and the focus on Palestine as a site of domestication, helped remake drylands as targets of colonization (Tesdell, 2017). Although the nascent state of Israel (1946) stood apart from the Cold War on hunger in the third world, it followed a very similar trajectory to other colonized territories in categorizing local agriculture. Policy discourses about local land use mythologized some agricultural practices and degraded others, using historical legal and scientific pretexts to justify intervention (Tesdell, 2013: 79, Salzmann, 2018). A primary theme was that Palestinian agriculture was degraded, backward, primitive, and that the landscape was wasted and barren. The Ottoman-Israeli legal apparatus was used to mark lands as uncultivated, thereby claiming them for the new state of Israel (Tesdell, 2013: 84; Cohen, 1993; Tyler, 2014). These fictions facilitated occupation, governance, and the cultivation of dependency. In June 1967, after brief but decisive conflicts with the surrounding Arab states, Israel occupied the West Bank, along with Gaza, Sinai and the Golan Heights. In the West Bank, Israel supported policies of agricultural modernization intended to bind Palestinian farmers to the Israeli state technical apparatus (Tesdell, 2013: 86). As local production declined and Palestinians entered the Israeli wage labor market, Palestine effectively became “a captive market for finished Israeli goods” (Abu-Sada, 2009).

While Israeli occupation took on distinctive forms, it shares features with the neoliberal, globalized food system derived from European imperial geopolitics: specifically, as Philipp Salzmann has characterized it, land grabbing, or “accumulation by dispossession. .. within the corporate food regime.” Israeli pretexts for land dispossession resembled those used in other settler colonies: displacing current inhabitants, characterizing territory as uncultivated, and casting peasant agricultural practices as primitive and unproductive. While the market replaced the state as the “primary guarantor of food security” after the 1970s, it remained sponsored and enabled by dominant states (Salzmann, 2018). The signing of the Oslo accords in 1993 left Palestine under the twin control of Israel and international finance institutions, marking a moment of neoliberal restructuring and defeat for a nationalist project of liberation (Salzmann, 2018; Samara, 2000). Specifically, the division of the West Bank into Areas A, B, and C, with Area C under full Israeli administrative control, normalized dispossession of Palestinian territory. This reordering paved the way for incursions of Israeli agribusiness and further contributed to the marginalization of rural communities based on peasant agriculture. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) further institutionalized asymmetries in power between states inherited from their imperial pasts, dictating loan conditions to the governing Palestinian Authority (PA) (Holt-Giménez & Shattuck, 2011; McMichael, 2009; Salzmann, 2018). The PA’s rural policy, outlined in the 2008 Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (PRDP), adopted a market vision for agriculture supported by international lenders (Salzmann, 2018). The PA’s acquiescence to neoliberal structural adjustment policies also hobbled community development initiatives and economies of resistance that had flourished during the first Intifada (1987–1993) (Kuttab, 2018).

The depoliticized development practice that took shape catered to donors rather than to communities. Palestine has received some twenty-four billion dollars of assistance since 1993 (Kuttab, 2018: 76). In 2008, the Agricultural Project Information System, managed by the Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture with assistance from the FAO, included some 170 international non-governmental, local nongovernmental and community-based organizations, UN agencies, and donors that represent the agricultural sector of West Bank and Gaza Strip (FAO, 2008). The PA remains subservient to the priorities of international actors and donors.

In this climate, international organizations have taken up the mantle of European colonial governments in shaping institutions and regulations to organize natural resources in occupied territory. International development agencies prioritize market potential for an expanded agricultural sector liberated from the impediments of occupation. UNCTAD emphasizes that Palestinian agricultural yields are 43% of Israel’s and half of Jordan’s. It recommends support required to develop Palestinian agricultural infrastructure, support farmer cooperatives, and stabilize production and transportation costs. The implicit goal is to increase the productivity of the Palestinian agricultural sector for the purposes of trade and development (UNCTAD, 2015).

In practice, agrobiodiversity and rural development projects cross formal and informal domains: CGIAR-funded agricultural research promoted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Palestinian NGO-directed community seed banks supported by international aid, and volunteer-based community organizations oriented toward Palestinian heritage and sovereignty. These various overlapping informal projects skate under the radar, contributing to a patchwork of data infrastructures and undocumented practices. This institutional drift, which is in many respects the product of a post-Oslo development landscape, creates a Swiss cheese of data infrastructures, which in turn masks a Swiss cheese of development and conservation priorities.

4 International Agricultural Research

Institutions dedicated to scientific research interface distinctively with Palestinian agriculture, even as they remain oriented toward market agriculture. In recent decades, biodiversity preservation advocates have emphasized that ex situ conservation of seeds in genebanks must be complemented by in situ conservation of traditional farming systems, which are often confined to drylands and mountainous areas not extensively cultivated for commercial purposes. While strategies for in situ preservation have been drafted by research funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF)/United Nations Development Program (UNDP), these programs have retained a primarily development-oriented perspective (Freeman et al., 2005). Such research emphasizes the adaptability of landraces to harsh conditions and low input agriculture, and it recommends the pursuit of increased yields through participatory breeding, water harvesting, conservation agriculture, and integrated pest management. These values also make biodiversity loss in arid regions an object of concern for international research. The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), established in 1977 in Tal Hayda, Syria, is the CGIAR center for the Middle East and North Africa, with a broader mandate to promote agriculture in non-tropical dry areas. Its stated mandate is to improve the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers in dry areas through delivery of its research output, working within national agricultural resource systems and directly with farmers. A GEF-funded, ICARDA-coordinated project on “conservation and sustainable use of dryland agrobiodiversity in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinian Authority and Syria” conducted eco-geographic and botanic surveys in 75 monitoring areas from 2000–2004, identifying threats to wild relatives of field crops, forage legumes and fruit trees. While overgrazing, wood cutting, poverty, and weak environmental protection laws posed threats in the region as a whole, the project identified the “political situation in the West Bank” as a primary threat to biodiversity (Amri et al., 2008).

In Palestine, ICARDA’s capacity building projects are channeled through the National Agricultural Research Center (NARC) in Jenin (Northern West Bank). These include its participatory plant breeding programs and the establishment of a gene bank targeting traditional varieties of cereals, legumes, and forage crops. NARC, which receives variable funding from the UNDP/GEF, the Ministry of Agriculture, the government of the Netherlands, and numerous international NGOs, pursues a range of research in the fields of rainfed agriculture, wastewater conversion, drought-tolerant crops, and informal seed production. ICARDA’s participatory plant breeding program, inaugurated in Syria in 1996, has been replicated in 11 countries, including NARC’s implementation in the West Bank (Nadar, 2018).

NARC’s Genetic Resource Unit (GRU) was the fruit of 2011 funding to support field crop landraces, ultimately resulting in the establishment of the gene bank in 2013. Its objectives are to support agrobiodiversity imperiled by climate change, drought, and disease. Consistent with CGIAR imperatives, the GRU regards crops and their wild relatives as material for breeding improved varieties. Also consistent with the CGIAR centers, its primary clients are researchers and institutions rather than individual farmers or the general public. The GRU provides the infrastructure for a national genebank, with all associated documentation practices. Collection targets ecologically and culturally precise regions: for example, central highland villages outside of Bethlehem and Hebron, known for their drought resistant wheat varieties. Researchers interview farmers about baladi varieties, with a focus on elders. Notably the same crop variety may have different names depending on the community in which the crop is grown, creating challenges in documentation. Collected seeds are studied for crop variations characteristic of baladi seeds. Accessions are multiplied, dried, catalogued, and split into short, medium, and long-term storage, with label noting GPS coordinates, scientific name, local name, date stored, and viability term (Nadar, 2018). NARC’s data standards are consistent with ICARDA’s and utilize passport descriptors.

The presence or absence of a national gene bank has major implications for the representation and claims to Palestinian flora. In the absence of an internationally recognized genebank, plants are collected in the Israeli National Genebank, often with different naming conventions. In addition, continued dependence on international donors and the Palestine National Authority’s Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) budgets imperils national agricultural research and agrobiodiversity preservation. Without adequate funding for collection and preservation, the gene bank may be underutilized. As an outcome of these conditions, and of continued lack of state recognition, Palestinian flora remain represented by proxy in the state of Israel and its scientific institutions. This condition exacerbates geopolitical inequalities in the production of scientific knowledge.

NARC’s goals conform to the MoA’s for “increasing agricultural production and productivity and improving livelihoods of the farmers” (MoA, 2013). The MoA strategy prioritizes food security in the West Bank with a fundamental market orientation. The primary targets of its research are grains and legumes, including wheat, chickpeas, and faba beans. NARC shares 70 dunums of land in Beit Qad with a Jenin farmers’ association, which benefits from partnership in participatory plant breeding trials and other projects. Farmers in the Jenin region, which is regarded as a breadbasket of Palestine, are comparatively well-served by both NARC and the MoA. This position of privilege may also translate into commitments to small-scale agriculture. Many of these farmers express a commitment to baladi seed production, articulated as commitments to Palestinian land inheritance and persistence on the land, as well as preferences for rainfed (ba’al) crops requiring less water and fertilizer. They express pride in their relationship with NARC in their production of seeds and knowledge for other farmers, including traditional varieties. They note, for example the superior qualities of smell, color, and flavor of baladi wheat varieties for traditional Palestinian cuisine in opposition to hybrid wheat stocks imported from Israel (Nadar, 2018).

Among NARC’s projects are surveys regarding participation in community, or informal, seed production, which it identifies as a target for increasing food security by decreasing imports and developing varieties well suited to dry conditions and rainfed agriculture (Istaitih et al., 2020). Community seed production also offers a strategy to reduce dependence on Israeli imports, shore up land claims, and resist the archiving of Palestinian flora as an Israeli national project. To determine farmer participation in informal seed production of wheat in Palestine, NARC conducted surveys of 145 farmers from major seed production sites in Palestine” (Istaitih et al., 2020). The survey aimed to ascertain who participated in these programs and why, finding that “farmers’ participation in seed production was significantly influenced by a range of factors, including seed source, planting date, rainfall and productivity, membership in agricultural association, technology adoption, capacity building, frequency of extension contact, and net returns and profit. The most important reason that the participants wanted to participate in the seed production was the access to improved input, the increase in rate of net returns, increase in profit and decreased production costs (Istaitih et al., 2020).

Toward that end, NARC works with agricultural cooperatives to distribute seed and promote best practices. In effect, agricultural cooperatives, liaising with NARC, become middlemen to community seed producers. These practices promote a range of technologies identified as appropriate to the region, including promotion of high yielding and drought tolerant forage crops/species and wild relatives, waste water conversion, scaling up of established water harvesting techniques, and best practices for cultivating medicinal and aromatic plants. The characterization of community production as informal, however valued and however accurate, underscores the market orientation of national agricultural research. Rural development and biodiversity preservation efforts at a national level bridge community empowerment, the PA’s market orientation, and movements for international recognition in governance and R&D.

5 Heritage Narratives

In contradiction to a neoliberal development model stand an array of community institutions, universities, and Palestinian NGOs committed to community prosperity through local stewardship of natural resources.

Independent of the Ministry of Agriculture’s sponsorship, Palestinian NGOs have led the charge in organizing farmers. This arrangement stems from the founding of multiple agricultural relief committees in the 1980s, primarily in the context of the first intifada (1987–1993). Now nearly forty years on, the politics of Palestinian agricultural NGOs bear faint resemblance to their founding moments, especially as international aid has altered the profile of each organization. Yet some features remain. The agricultural NGOs focus on control of natural resources, including land and water, as a means to achieve both self-sufficiency and territorial sovereignty. They pursue the cultivation of land, primarily through rainfed agriculture, both to diminish dependence on Israeli goods and to forestall Israeli confiscation of uninhabited lands. Like NARC, these NGOs support agricultural modernization to enable competition with Israeli producers; and they organize agricultural cooperatives throughout the West Bank. Cultivating land makes it inaccessible for settlement or protective restrictions applied to nature preserves (Abu-Sada, 2009: 416).

NGOs provide an example of community biodiversity management (CBM) approaches prioritizing community-driven, participatory approaches to biodiversity management and local and subsistence farming (Nadar, 2018; Subedi et al. 2006; Thijssen et al. 2013). Community seed banks have been widely established in Asia, Latin America, and Africa beginning in the 1980s. The Middle East has lagged behind these trends. Advocates hold that CBM empowers farming communities to promote conservation and use of local biodiversity, further aided by partnerships with institutions of research and development (Boef, 2013). Community based seed banks are not necessarily incompatible with national strategies. Several Palestinian NGOs (Union of Agricultural Work Communities [UAWC], Palestinian Agricultural Relief Committees [PARC], Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem [ARIJ]) and universities [Al Najah, Al-Quds, Al-Azhar]) have an MOI with the Ministry of Agriculture and NARC in an attempt to avoid duplication of efforts (Zayed, 2020).

In practice, Palestinian NGOs constantly renegotiate their relationship to international networks of science and capital. NGOs nevertheless prioritize community needs rather than national or international ones. Community seed banks also operate with a shorter time-scale, serving the farmers of the present rather than those of a hypothetical future. To some extent, this frees them from the arts of abstraction and renders immediate their pursuit of drought-resistant crops for which there is local demand: Battir eggplant, Dura serpent squash, and tomato. Moreover, overt orientation toward food sovereignty injects human social life into any ecological equation.

Nor is biodiversity preservation confined to national governmental and non-governmental organizations. At the university level, nearly every Palestinian University has departments and centers dedicated to water resource management and sustainable land use. At the community level, Um Selim farm, the Bethlehem Farmers’ Association, Bustana Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), and the Heirloom Seed Library in Battir, among others, prioritize the preservation of local seed varieties. These are grassroots organizations operating independently of institutionalized research and development.

Perhaps the most well publicized of these is the Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library directed by Vivien Sansour. In 2018, Al Jazeera dubbed Vivien Sansour “the Seed Queen of Palestine” (Anonymous, 2018). Four years earlier, Sansour founded the seed library and the associated organization El Beir Arts and Seeds, crowd-sourcing via Facebook and combing markets to find traditional seeds being cultivated in Palestine. Sansour prioritizes “seed revival” rather than seed saving, enlisting farmers in her project through a mix of enthusiasm and persistence. As a sequel to the Seed Library, she founded the Traveling Kitchen, which hitches itself to a truck and travels from town to town, cooking up the produce of the library. In this practice, she builds on her previous work at Canaan, an olive and almond Fair Trade company selling for export (Nadar, 2018).

The Seed Library is small, enrolling 20 farmers and 4 threatened varieties, including Jadu’i watermelon, white (Sahour) cucumber, and Abu Samra (“father of the dark one”) wheat, also sometimes called Kahla (“dark eyes”), or Haba Soda (“dark seeds”). (The variety is named for its long, dark awns and dark seeds.) Sansour also raises awareness of wild plants used in Palestinian cuisine. The Israeli government now classifies Akkoub, a thistle commonly used in Palestinian cuisine, as an endangered species. With collection prohibited by law, foraging has become a site of conflict, with Palestinian youth detained by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Sansour and others hold that the expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank is a primary driver in the plant’s endangerment. She adds settlements to Israeli agribusiness and climate change as threats to traditional agriculture.

The Seed Library begins by identifying baladi seeds with the aid of local farmers. Seeds are catalogued with crop name and year collected, placed in jars, and shelved in the Seed Library headquarters in Beit Sahour. The library retains seeds for less than a year. The priority is to distribute seeds to farmers, who may “check out” seeds and replenish the stock at the end of the season. As of 2018, the Library housed 40 varieties of baladi seeds. Along with the seeds, the Library records stories associated with the crops. It also pursues alternative food networks linking producers and consumers outside of regular market structures (Nadar, 2018).

Sansour is a master storyteller. Putting aside the value of biodiversity and climate change resistance, she links seeds to stories of identity and belonging. Perhaps deliberately choosing a genetic metaphor, she offers that “seeds carry the DNA of who we are, our culture, the work of our ancestors” (Nadar, 2018). She aims to promote agriculture by telling the stories that have made it durable. Hers is a strategy to combat knowledge loss and retain the oral tradition of agriculture, which precedes written language, never mind digital infrastructures.

Sansour has well-trafficked stories about Battir’s ancient terracing and aqueduct system (now a UNESCO World Heritage site), and the havoc wreaked by the snaking of the Green Line across its borders. (Only concerted effort by Palestinians and Israelis preserved the village and surrounds from demolition for the construction of the Separation Wall tracking the Green Line.) She celebrates Battir’s baladi seeds as continuously cultivated since the second c. BCE. El Beir sponsors terrace revival in the zone of the wall, including the planting of mulukhiya for stew. Sansour tells stories about how women remember giving birth among the Jadu’i watermelons, and about the Quality Street chocolate tins full of seeds kept in every grandmother’s drawer. She talks about cooking purple carrot stuffed with pine nuts and rice (Anonymous, 2018). These stories remind us that women are the majority of the world’s farmers, and that seeds belong to communities. Fundamentally, her work is about reminding people of their worth and their sense of belonging, in opposition to the imperatives of the market, the constraints of international aid, and the imposition of neoliberal approaches to development in the Middle East and North Africa.

Perhaps it is no surprise that Sansour’s interest in agriculture was provoked by her experience in Chiapas, Mexico, where she helped build a cistern for highland coffee growers. During a break, an elder served the team papaya grown from his great grandfather’s seeds, inspiring Sansour to consider her own agricultural heritage in Palestine. Chiapas, the site of the anti-NAFTA Zapatista rebellion in 1994, became a center of anti-globalization and indigenous activism in the 1990s. Efforts by the International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups (ICBG) and prominent ethnobotanists to collect Mayan medicinal plants and knowledge collapsed amid charges that ICBG’s commercial partners included numerous transnational pharmaceutical and agrochemical companies (RAFI, 1999; Berlin & Berlin, 2003, 2004; Hayden, 2003). The specter of Chiapas haunts twenty-first-century biodiversity collecting enterprises, suggesting that the preservation has always been coupled with exploitation. The proper relation between smallholder agriculture and commercial monoculture remains unresolved, as do broader questions of how local communities should interface with international markets.

Sansour and her collaborators reject the globalizing force of the market. They embrace participatory as opposed to technocratic projects, drawing on the knowledge and engagement of communities. This approach echoes those which elevate traditional environmental knowledge and local knowledge, and promote community involvement in restoration projects. In doing so, they may (or may not) acknowledge the variability of collective memory, preferences, and values in dictating the meanings of the past. (Alagona et al., 2012; Eliott, 2008). These allowances, however consciously made, create a conundrum for the collection and transcription of data, inasmuch as they call into question the very idea of data as “the givens.” One farmer who grows hybrid and traditional varieties was asked about the benefits of the latter, to which he replied: “hybrids can give me high yields, but it’s not consistent. Hybrids breakdown the soil, eventually stops producing. Baladi is consistent, and you get to preserve your country, conserve your tradition. Baladi is timeless” (Nadar, 2018). Here, the data is the story, and it is meaningful in the act of retelling.

But there is no such thing as a timeless seed.

6 Agroecosystems

If the vocabulary of taxonomy and genomics universalizes targets of preservation, agroecology prioritizes locality. Through the research group Makaneyyat, which he co-founded in 2015, geographer Omar Tesdell and his collaborators aim to conserve local agrobiodiversity and develop perennial agroecosystems that support polycultures (Tesdell et al., 2020). They see this as a strategy to combat the massive decline of agriculture in Palestine, including wheat, barley, and pulses like lentil and chickpea. They attribute this shift to the transition to wage labor in the Israeli economy, as well as Israeli policies restricting access to land, water, and markets. Olive production provides the single counter-example to a trajectory of agricultural decline. Yet olives themselves were formerly components of polycultures (e.g. olive-grape-wheat), which historically promoted soil health and community subsistence. Tesdell and team aim to design perennial polycultures within existing olive groves with the objectives of improving biodiversity, reducing tillage, rebuilding soils, and providing resilience for climate change.

The founding of Makaneyyat resulted in the compilation of large and diverse data sets consisting of archival sources, aerial images, interviews, and fieldwork. Makaneyyat’s methods encompass the frameworks of landscape ecology, geography, and ethnobotany, and history. The research group uses an open-source agroecological research engine, “which allows researchers to manipulate, filter, visualize, and store agroecological data in order to drive their own investigations” (Tesdell et al., 2020). Given the interdisciplinary nature of the work, the archive consists of genetic material, geodata, and ethnobotanical information. In addition to polyculture design, its work encompasses in-situ and ex-situ conservation of wild food plants and crops, as well as digitization of existing primary source floras of Palestine. A priority of the project is on the “lived experience and knowledge of local farmers and foragers to coproduce knowledge that is relevant to Palestinian communities and agroecosystems.” Makaneyyat draws inspiration from Wes Jackson’s Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, which aims to develop new perennial grain crops adapted to the prairie’s native ecosystem. Makaneyyat collaborates with the Land Institute on research design, candidate selection, and community-based approaches, including “the use of open science models to build climate adaptation into agriculture,” developing perennial grain culture oriented toward ecosystem stability (Tesdell et al., 2020).

Acknowledging the historical wealth and complexity of Palestinian agriculture, Makaneyyat and others are less concerned with restoration than attempts to create ecosystems for the future. These projects martial historical evidence and claims about the past to attempt renewed production and partial reconstruction of agrarian landscapes transformed by colonization and occupation. But this makes them ill-fitted to the data regime constructed under the auspices of the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, which aims to protect farmers’ rights by insisting that their knowledge and labor belongs to the world (FAO, 2009: v).

Drawing on social ecological and agroecological approaches, Makaneyyat attends to the social as well as biophysical aspects of agriculture in its approach to community and socioeconomic relations. By extension, its approach acknowledges the value of historical agricultural inputs (here, seeds and crop wild relatives); but it regards them as components of a social system rather than isolated variables, and it considers the social system rather than the inputs to be its primary focus. It explicitly rejects the “agrilogistical” approach of annual grain culture, which holds people apart from nature and demands intensive disturbance of local ecosystems. It finds patriarchy and settler colonialism implicated in the broader shift to input-intensive and carbon exploitative agriculture of scale (Streit Krug & Tesdell, 2020).

This overtly utopian outlook on perenniality and diversity, oriented clearly toward social relations rather than technological solutions, sits awkwardly in an international system targeting seeds as determinative inputs of successful agricultural systems. It also scales poorly, focused as it is on the precise needs and configurations of local communities. That is, its “landscape-scale agricultural intervention” makes plant knowledge a social process rather than an object to be universalized as data.

Makaneyyat at odds with related projects constructed on values and infrastructures of improvement, development, capitalism, and settler colonialism; but it does not exist in isolation from them, nor in simple opposition. Rather, Makaneyyat draws widely on available technologies, leveraging global datasets as well as local observations to build knowledge about the Palestinian landscape. Its architects regard gene editing not as a bogeyman but as a path to domestication of new crops for degraded and stressed environments (Van Tassel et al., 2020). It seeks to ally itself with open-source software and seed movements through the adoption of open-source data management and storage tools. Arguably these are ideological commitments as well as practical ones; but they nevertheless set the stage for future projects that take collaborative labor as the basis of agricultural knowledge rather than an object to be secured or commodified. In policy terms, openness and transparency provide the technical basis for just social relations to devise novel agroecosystems.

7 Conclusions

As Alfred Lotka and his heirs brought mathematics to ecology, so has big data come to biodiversity. But it is not clear where to go from here. Since their 2016 publication, the FAIR data principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability have been endorsed by a broad range of stakeholders in digital data (Jacobsen et al., 2020). This wide acceptance signals the ascendance of Open Science as an international movement, and of FAIR in the age of Big Data (Mons et al., 2017).

Good data stewardship, however, is incomplete without a more broadly based ethics and practices of stewardship to undergird it. That is, these are not merely questions of implementation, but rather questions about the quality and scope of the data itself. In summary, “the givens” itself never was.

FAIR provides regulations for access to data, but, ironically, these may further limit the scope of the data itself, disqualifying legacy collections or sources badly suited to reduction. Too often, open source data projects manage to excel at the stated principles of access and usability while still failing to make room for other forms of qualitative data, narrative sources, and archival material. Scholars oriented towards “communities of practice” have pursued alternative formulations for data collection, but they remain hamstrung by inability to scale up to the level of big data (Louafi et al., this volume). In response to the limits of FAIR, the International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group of the Research Data Alliance has developed ‘CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance’ (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics) (Carroll et al., 2020). These guidelines were the products of consultations with Indigenous Peoples, scholars, non-profit organizations, and governments, and authored by a network of Indigenous data sovereignty networks. Like FAIR, CARE specifies principles with little guide to application. But their publication is a clear demand to orient conversations about international data sharing away from the funding bodies who endorse FAIR, and toward the communities they have too often failed to engage.

NARC, Makaneyyat, and El Beir provide different approaches to interfacing with international agricultural research data infrastructures and the Open Source data platforms that have gained traction in the past decade. Their varied paths suggest that there is no technological end run around the social and political problems posed by international agricultural development and biodiversity preservation initiatives, but rather an approach to technology as a set of diverse material practices associated with particular communities. By representing the values of communities in their data collection and preservation, these institutions aim to counter exclusions reproduced in the legacies of imperial science and governance.

Between science, policy, and community are the spaces to be cultivated. In Palestine, it’s often difficult to get farmers on board with agricultural development programs for many reasons: because these programs should pay, and they don’t. Because they should make things easier, and they can’t. Because although it may be an ecologically appropriate technology, no one wants to manually dig hundreds of curved swales in the ground to channel rainwater: because, whether or not it was traditional agricultural practice in the region, it is back-breaking labor, and the returns don’t justify it. Because no one wants to grow vegetables they can’t sell amid a glut of lower priced Israeli products. In place of market incentives, there are fervent political commitments to Palestinian sovereignty and heritage, with farming deployed to prevent land seizures and to promote solidarity and community. These very commitments mitigate participation in neo-colonial and neoliberal international development projects. Data won’t be FAIR until it speaks to the needs and desires of these communities so pervasively excluded from the benefits of international development.

References

Abu-Sada, C. (2009). Cultivating dependence: Palestinian agriculture under the Israeli occupation. In A. Ophier, M. Givoni, & S. Hanafi (Eds.), The power of inclusive exclusion: Anatomy of Israeli rule in the occupied Palestinian territories. Zone Books.

Alagona, P. S., Sandlos, J., & Wiersma, Y. F. (2012). Past imperfect: Using historical ecology and baseline data for conservation and restoration projects in North America. Environmental Philosophy, 9(1), 49–70.

Altieri, M. (1995). Agroecology: The science of sustainable agriculture. Westview Press.

Amri, A., Monzer, M., Al-Oqla, A., Atawneh, N., Shehadeh, A., & Konopka, J. (2008). Status and threats to natural habitats and crop wild relatives in selected areas in West Asia region. Proceedings of the International Conference on Promoting Community-Driven In Situ Conservation of Dryland Biodiversity. 18-21 April 2005, ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria.

Anker, P. (2001). Imperial ecology: Environmental order in the British empire, 1895–1945. Harvard University Press.

Anonymous. (2018) The Seed Queen of Palestine. Al Jazeera News, December 10. https://www.aljazeera.com/program/witness/2018/12/10/the-seed-queen-of-palestine

Berg, T. (2009). Landraces and folk varieties: A conceptual reappraisal of terminology. Euphytica, 166(3), 423–430.

Berlin, B., & Berlin, E. A. (2003). NGOs and the process research: The Maya ICBG project in Chiapas, Mexico. International Social Science Journal, 55(178), 629–638.

Berlin, B., & Berlin, E. A. (2004). Community autonomy and the Maya ICBG project in Chiapas, Mexico: How a bioprospecting project that should have succeeded failed. Human Organization, 63(4), 472–486.

Buerstmayr, M., Huber, K., Heckmann, J., Steiner, B., Nelson, J. C., & Buerstmayr, H. (2012). Mapping of QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance and morphological and developmental traits in three backcross populations derived from Triticum dicoccum × Triticum durum. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 125(8), 1751–1765.

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueora-Rodriguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J. D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. (2020). The CARE principles for indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal, 19, 43. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043

Cronon, W. (1992). A place for stories: Nature, history, and narrative. The Journal of American History, 78(4), 1347–1376.

Cronon, W. (1993). The uses of environmental history. Environmental History Review, 17(3), 1–22.

Curry, H. (2017). From working collections to the World Germplasm Project: Agricultural modernization and genetic conservation at the Rockefeller Foundation. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 39(5).

Davis, D. K. (2009). Historical political ecology: On the importance of looking back to move forward. Geoforum, 40(3), 285–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.01.001

Davis, D. K. (2015). Historical approaches to political ecology. In T. Perreault, G. Bridge, & J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of political ecology. Routledge.

Drayton, R. H. (2000). Nature’s government: Science, imperial Britain, and the “improvement” of the world. Yale University Press.

Ehrlich, P. (1968). The population bomb. Ballantine Books.

Eliott, R. (2008). Faking nature: The ethics of environmental restoration. Routledge.

FAO. (2009). International treaty on plant genetic resources. FAO. https://www.fao.org/3/i0510e/i0510e.pdf

FAO. (2008). Agricultural projects in the West Bank and Gaza Strip 2008. Agricultural Projects Information System (APIS) report. FAO. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-203615/

Fenzi, M., & Bonneuil, C. (2016). From “genetic resources” to “ecosystems services”: A century of science and global policies for crop diversity conservation. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment, 38(2), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/cuag.12072

Flitner, M. (2003). Genetic geographies: A historical comparison of agrarian modernization and eugenic thought in Germany, the Soviet Union, and the United States. Geoforum, 34(2), 175–185.

Freeman, J., Mehdi, S., & Duwayri, M. (2005). Conservation and sustainable use of dryland agrobiodiversity, Jordan/Lebanon/Syria/Palestinian authority, terminal evaluation final report. December 2005, United Nations Development Program Evaluation Resource Center. https://erc.undp.org/evaluation/documents/download/849.

Fullilove, C. (2017). The profit of the earth: The global seeds of American agriculture. University of Chicago Press.

Grove, R. (1995). Green imperialism: Colonial expansion, tropical Island Edens, and the origins of environmentalism, 1600–1860. Cambridge University Press.

Hayden, C. (2003). When nature goes public: The making and unmaking of bioprospecting in Mexico. Princeton University Press.

Holt-Giménez, E., & Shattuck, A. (2011). Food crises, food regimes and food movements: Rumblings or ferorm or tides of transformation? Journal of Peasant Studies, 38, 109–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.538578

Huneman, P. (2019). How the modern synthesis came to ecology. Journal of the History of Biology., 52, 635–686.

Istaitih, Y., Alimari, A., & Jarrar, S. (2020). Determinants of farmers’ participation in informal seed production for wheat in Palestine. Research on Crops, 21(1), 186–176. https://doi.org/10.31830/2348-7542.2020.028

Jacobsen, A., de Miranda Azevedo, R., Juty, N., et al. (2020). FAIR principles: Interpretations and implementation considerations. Data Intelligence, 2(1–2), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_r_00024

Kingsland, S. (1995). Modeling nature: Episodes in the history of population ecology. University of Chicago Press.

Kuttab, E. (2018). Alternative development: A response to neo-liberal de-development from a gender perspective. Journal für Entwicklunspolitik, 34(1), 62–90. https://doi.org/10.20446/JEP-2414-3197-34-1-62

McMichael, P. (2009). A food regime analysis of the ‘world food crisis’. Agriculture and Human Values, 26, 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9218-5

Mitman, G. (1992). The state of nature: Ecology, community, and American social thought, 1900–1950. University of Chicago Press.

Mons, B., Neylon, C., Velterop, J., Dumontier, M., da Silva Santos, L. O. B., & Wilkinson, M. D. (2017). Cloudy, increasingly FAIR; revisiting the FAIR Data guiding principles for the European Open Science Cloud. Information Services and Use, 37, 49–56.

Nadar, D. (2018) How community saving of traditional seeds promotes agrobiodiversity and farmer autonomy in the West Bank, Palestine. M.A. thesis, American University of Rome.

Pauly, P. J. (2007). Fruits and plains: The horticultural transformation of America. Harvard University Press.

Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI). (1999). Biopiracy Project in Chiapas, Mexico Denounced by Mayan Indigenous Groups. News Release, December 1. www.rafi.org

Salzmann, P. (2018). A food Regime’s perspective on Palestine: Neoliberalism and the question of land and food sovereignty within the context of occupation. Journal für Entwicklunspolitik, 34(1), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.20446/JEP-2414-3197-34-1-14

Samara, A. (2000). Globalization, the Palestinian economy, and the “peace process”. Journal of Palestine Studies, 29(2), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676534

Saraiva, T. (2013). Breeding Europe: Crop diversity, gene banks, and commoners. In N. Disco & E. Kranakis (Eds.), Cosmopolitan commons: Sharing resources and risks across Borders. MIT Press.

Simberloff, D. (1988). The contribution of population and community biology to conservation science. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 19, 473–511.

Soulé, M. E. (1985). What is conservation biology? Bioscience, 35(11), 727–734.

Streit Krug, A., & Tesdell, O. I. (2020). A social perennial vision: Transdisciplinary inquiry for the future of diverse, perennial grain agriculture. Plants, People, Planet, 3(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10175

Tesdell, O. (2013). Shadow spaces: Territory, sovereignty, and the question of Palestinian cultivation. PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota. https://hdl.handle.net/11299/174898

Tesdell, O. (2017). Wild wheat to productive drylands: Global scientific practice and the agroecological remaking of Palestine. Geoforum, 78, 43–51.

Tesdell, O., Othman, Y., Dowani, Y., Khraishi, S., Deeik, M., Muaddi, F., Schlautman, B., Streit Krug, A., & Van Tassel, D. (2020). Envisioning perennial agroecosystems in Palestine. Journal of Arid Environments, 175, 104086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2019.104085

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2015). The besieged Palestinian agricultural sector. United Nations. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsapp2015d1_en.pdf

Van Tassel, D. L., Tesdell, O., Schlautman, B., Rubin, M. J., DeHaan, L. R., Crews, T. E., & A Streit Krug. (2020). New food crop domestication in the age of gene editing: Genetic, agronomic and cultural change remain co-evolutionarily entangled. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00789

Zayed, D. (2020). Interview by Courtney Fullilove at UAWC Local Seed Bank. Ramallah.

Zohary, M., & Feinbrun-Dothan, N. (1966). Flora Palaestina. Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fullilove, C., Alimari, A. (2023). Baladi Seeds in the oPt: Populations as Objects of Preservation and Units of Analysis. In: Williamson, H.F., Leonelli, S. (eds) Towards Responsible Plant Data Linkage: Data Challenges for Agricultural Research and Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13276-6_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13276-6_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-13275-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-13276-6

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)