Abstract

This chapter details the challenges of mutual digital communication, particularly pressing in light of the geopolitics of the blockade in the Gaza Strip, where conditions are deteriorating and many live below the poverty line. I became acquainted with these challenges through the process of founding and implementing an initiative to connect student refugees in Gaza with undergraduate student interlocutors in the United States. As part of the outreach, participants reflected upon the historical background of the crisis of refugee displacement in the Gaza Strip—the world’s third most densely populated territory. Student conversations, via WhatsApp video chats and voice messenger, also forged intercultural bridges and encouraged leadership. The experience in a nontraditional classroom environment promoted student advocacy and enriched the curriculum for both U.S. students and students in Gaza learning about civic engagement.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

This chapter details the challenges of mutual digital communication, particularly pressing in light of the geopolitics of the blockade in the Gaza Strip, where conditions are deteriorating and many live below the poverty line. I became acquainted with these challenges through the process of founding and implementing an initiative to connect student refugees in Gaza with undergraduate student interlocutors in the United States. As part of the outreach, participants reflected upon the historical background of the crisis of refugee displacement in the Gaza Strip—the world’s third most densely populated territory. Student conversations, via WhatsApp video chats and voice messenger, also forged intercultural bridges and encouraged leadership. The experience in a nontraditional classroom environment promoted student advocacy and enriched the curriculum for both U.S. students and students in Gaza learning about civic engagement.

In this chapter, I provide a toolkit for educators looking to explore similar opportunities for their students. Between Spring 2017 and Fall 2021, I developed this opportunity and incorporated it into undergraduate courses listed or cross-listed in a variety of departments, including Communication, Political Science, Modern Languages and Cultures, and History. Each course was unique, and, in each iteration, I tailored the exchange experience, which usually represented 25–30 percent of students’ final grade, to the specific context of the curriculum. Throughout the semester, students in the U.S.-based course were connected with pre-professional students in Gaza. U.S.-based students took this course for credit, while the students in Gaza participated for enrichment. After describing the goals and outcomes of the exchange, I will identify areas for further development; for instance, though the pilot program focused on undergraduate students who identify as women, my aim is to expand the initiative to include students of all genders. As I show, such partnerships pose significant challenges, even as they offer great benefits to campuses seeking to foster global engagement and student advocacy in the twenty-first century.

A Different Pedagogical Approach in Social Justice: De-escalation Can Work

Through this exchange, undergraduate students in the Hudson Valley, New York, and in the Gaza Strip, Palestine, participated in a global engagement initiative to build intercultural bridges and promote mutual understanding of cultural differences through active listening and empathy in a nontraditional classroom setting. This program was piloted at more than one institution of higher learning in the New York region. Because of the sensitive nature of regional politics in the Middle East, I have elected not to name the institutions in order to protect participating students and ensure future collaborations.

My primary goals were to develop a transformative social justice pedagogy and course delivery, with the aid of WhatsApp; to persuade partners (students and faculty alike) to assess the potential learning outcomes associated with this global engagement; to adapt to the risks associated with computer-mediated communication (CMC) in areas of conflict; and to support women’s agency in global contexts.

The effort to foster greater global engagement in academia has been greatly influenced by the theoretical frameworks of cross-cultural communication (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2010; Thomas 1994; Thomas 2006). Such cross-cultural communication is necessary to establish feelings of trust and enable cooperation despite cultural barriers, misunderstandings, prejudice, racism, stereotypes, and conflicts between East and West. Models that incorporate student activism and horizontal relationships can defy preconceived notions about refugees and immigrants (Kim 1998). Despite growing student activism on behalf of migration, refugees, and displacement, critical pedagogy about Palestine remains difficult in the United States. In light of students’ desire for community-engaged learning and social activism, it is important to continue sharing successful pedagogical models. I suggest here that using digital communication is indispensable in creating such critical pedagogical practices.

For this purpose, peer conversations via WhatsApp turned out to be a transformative tool for student activism and advocacy. These connections enabled Hudson Valley undergraduates to understand more deeply the nature of the conflict, while building new intercultural bridges between the Gaza Strip and the Hudson Valley. Peer conversations also boosted hope. WhatsApp voice messages served as a key tool for preserving computer-mediated communication (CMC) at times when censorship and surveillance of the Gaza Strip residents prevented planned WhatsApp phone calls and live video calls. The course was built on these interpersonal connections, in a framework of global community-based learning (rather than service learning).

What Is Challenge2Change?

The goals of my course aligned with the mission of a nongovernmental organization called Challenge2Change. The organization empowers refugee women and young women in areas of conflict across the Middle East, supports their well-being, provides opportunities for both mentorship and leadership, and supports participants as they transform challenges into positive experiences.

Challenge2Change facilitated the recruitment of Gazan undergraduates for this global community-based learning initiative, and I committed to mentoring Gaza-based students for the duration of the exchange. Within twelve hours of setting up the online application, we had received applications from 65 undergraduates from both urban areas and refugee camps within the Gaza Strip. From this pool, Challenge2Change selected students based on grades (no lower than C) and English proficiency (beginner or intermediate). In the end, the selected student group came from many different academic disciplines and departments: Business, Computer and Information, Engineering, Liberal Arts and Sciences, Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmaceutical. Students made a verbal commitment to the exchange, and they agreed to read news articles in English on the course’s assigned topics to prepare for their conversations with U.S. students.

On the U.S. side of the exchange, undergraduate students applied by submitting a resume and participating in video interviews. During these individual interviews, typically 45 minutes long, students were briefed on the nature of the global community-based learning initiative. Participants then had to read an assigned article and later conduct self-directed scholarly research to understand the complicated nature of the project and the living conditions their Gazan counterparts endure. The U.S.-based students who have participated in the exchange have a wide variety of academic interests; the exchange has included students majoring in STEM subjects, such as Mathematics, Computer Science, and Biology as well as humanities and social science majors interested in Communications, Foreign Languages, Political Science, Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, History, Theater, and Music.

This particular exchange was offered as a civic engagement option, one element to enrich courses that explore themes like refugees, migration, and racism. Given the subject’s sensitivity, students could opt out of this civic engagement opportunity and instead work with a local community organization, For The Many. For those students who opted into the partnership with Challenge2Change, one of the course expectations was to fundraise $50 at the end of the semester, in order to enable some of the Palestinian students participating in this project to enroll in English courses taught at AMIDEAST in the Gaza Strip. Each English course and its textbook cost $150—in an area where the average individual makes $2 or less per day and child labor is the norm, as reported by the United Nations Children’s Fund and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (Bureau of International Labor 2019).

Intercultural Communication Competence and Tenacity

Our undergraduate students in the Mid-Hudson Valley interacted with young women who pursued their college educations despite disruption from political violence in the Gaza Strip and dire socioeconomic situations. Students connected via video conference, WhatsApp, and social media. At times, students were limited to voice calls only (via WhatsApp) in light of the blockade, which limited access to electricity and Wi-Fi to four hours per day in the Gaza Strip. Another persistent challenge was the seven-hour time difference between New York and Palestine. These practical challenges became the basis for growth. The New York students learned that the dictum that “time is money” that cannot be wasted is a culturally embedded belief, not a universal principle. For their part, the Gazan students had to navigate the program’s tight schedule, despite lacking control over their time in a volatile political situation.

Given the unique circumstances surrounding this civic engagement, all participants were strongly determined to figure out strategies and work around these challenges. Some participants in Gaza borrowed cell phones from relatives, friends, neighbors, and friends of friends. Meanwhile, American students committed to adjusting their schedules as circumstances required. All participants were highly motivated to make these intercultural exchanges a reality. Many participants in Gaza wanted to participate in order to enhance their English language proficiency; practical motivations drove students with goals for professional development or plans for further study. In response to the deteriorating humanitarian conditions in the Gaza Strip, we wanted to reinforce connections between the student refugee population and the outside world.

As Gaza students enhanced their language capacities, American students questioned their assumptions, rethinking the way they perceived accents associated with non-native English speakers. Throughout the process, American students expressed their appreciation of Gazan students, who had minimal prior exposure to English. As a result of the experience, U.S. students developed greater tolerance to support Gazan students’ language learning during interactive sessions.

Through ten virtual meetings over ten weeks, students had intercultural exchanges in English about daily life in both societies. We explored cultural history, religion, politics, travel (freedom of travel vs. restricted movement), unemployment, healthcare communication and systems, and education. In Spring 2020, we added Covid-19 to the list of topics.

New York participants developed an understanding of what it means to live in an open-air prison, where metaphors of the blockade, siege, trauma, crisis, occupation, terror, and resistance contextualize Gaza’s everyday reality (Tawil-Souri and Matar 2016). Gaza has become “unlivable,” according to the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, who insisted that all parties—particularly Israel—bring an end to this disaster. Eight hundred thousand people drink contaminated water, and two million people navigate a collapsed healthcare system, per the UN report, in a territory with the third-highest population density in the world (Berger and Balousha, 2020). Also, the Israeli series of wars with Hamas led to more severe food insecurity in the Gaza Strip, unemployment at 48 percent, and poverty above 50 percent even before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and hostilities during the 11-day war in May 2021 (Abu Amer 2021; Azaiza 2020; Lynk 2018; Macintyre 2019; Schlein 2018; Trew 2019). It is extraordinarily difficult for these young learners to pay for professional development services, such as educational centers or workshops that advance their learning and careers. The class prompted students to identify patterns across borders—connecting, for example, water contamination in Gaza and in Flint, Michigan (Williams 2020). In sum, civic mindfulness empowers individuals to question the dominant power structure and to see how their everyday worries and insecurities are linked to the social and economic contexts of their everyday lives (Purser 2019).

For the New York students, the main purpose was to provide an opportunity for virtual, intercultural exchanges with a population continuously living the norm of internal displacement. They needed to understand the unthinkable magnitude of suffering and the depth of the crisis as a result of Palestinian-Israeli conflict. It is indispensable to listen to stories that are not only unique but also often unpublicized by mainstream media in the United States and Europe.

Self-determination and tenacity empowered interpersonal connections in this virtual setting. Furthermore, the exchange was affirming for students in both locations, supporting participants’ sense of agency and galvanizing their engagement with their respective communities on the ground. In their one-on-one interactions and in papers, participants acknowledged each other’s strengths and the benefit of a more horizontal exchange of ideas.

Resilience Through Connection and Exchange

In addition to academic and cultural learning, an unexpected benefit of the program was a sense of social and emotional support. According to Gazan students, these intercultural exchanges served as an important coping mechanism to support their well-being, even for a short period of time. Before the 11-day Israeli aggression in May 2021, the Gazan students were already terrorized and traumatized from the collective punishment of daily Israeli strikes that go unreported in Western mainstream media. The ten weeks of our sessions offered a temporary escape from the horror of bombardments, a sentiment participants expressed over WhatsApp voice messaging exchanges.

Gazan students were also surprised that their American counterparts were not aware that successive U.S. presidential administrations have provided nearly $4 billion a year in military aid to Israel. Mid-Hudson Valley students left the course with a nuanced understanding of the United States’ role in Gaza. While some expressed their support of past United States policy in the Middle East, they also denounced the consequences of that policy upon residents of Gaza. During one iteration of the class, in Spring 2019, Israeli military aggression in Gaza cut off electricity and Wi-Fi; our class was able to reconvene only after the Gazan students mourned the deaths of family and friends. The New York students expressed authentic concern for their counterparts in the aftermath of the Israeli strikes, and the experience led them to question America’s claim to be a global leader in human rights.

The participants found such experiences extremely valuable; both American and Gazan students strengthened their ability to reciprocate different learning experiences, understand cultural differences, and question global issues. De-escalation within these intercultural exchanges is key at times, when participants have challenged one another to think critically about political discourses about the nature of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the Palestinian diaspora, undocumented immigration, United States foreign policy, cultural hegemony, imperialism, and post-colonization.

Assessment Recommendations

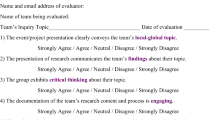

By working with young women whose lives are shaped by their families’ displacement in Gaza, students based in New York could develop a more concrete sense of the impact of communication, conduct, and the pragmatic interplay of geopolitics on the livelihoods of civilians and refugees alike in the Gaza Strip. This process of intellectual growth was further cultivated in a rigorous reflection essay that integrated hands-on experiences and civic engagement with communication concepts and theories.

U.S.-based students wrote a reflection paper that briefly described activities undertaken through the project, connected the theme of civic engagement with material covered in the content of the class, and formulated a concrete takeaway about how the experience can be applied to professional and personal goals. Students strove to be specific, concrete, theoretical, and analytical in the final paper. The paper required students to integrate discipline-specific concepts and theories with their hands-on experiences; students wrote about how the experience applied to their current lives and future research trajectories in fields like communication, computer-mediated communication (CMC), refugees, and/or displacement (Kim 1998; Burton 1999).

Finally, the student learning outcomes from this global engagement initiative defied the stereotypical notions of migrants and refugees frequently conveyed by the United States media. Overall, this civic engagement project linked the challenging circumstances of displaced people to uncontrollable political oppression and socioeconomic circumstances. The lack of opportunity in the Gaza Strip was eye-opening to many of the Hudson Valley students, negating the traditional American values of hard work, upward mobility, and individualism. Even the most educated populations and upper-class families in the Gaza Strip nevertheless faced the devastating ramifications of political violence there.

Students’ cultural sensitivity increased to develop a further understanding of the humanitarian implications of closed borders and harsher immigration policies. Also, it allowed them to examine contemporary issues of undocumented immigration and forced displacement with more depth and from different perspectives. The project also triggered their interest in exploring in future research the ethical issue of the refugee plight in Gaza from a legal standpoint.

Conclusion

The spread of Covid-19 disrupted our constructs of traditional academic venues, that is, face-to-face classrooms. However, the participants’ familiarity with online, community-based global engagement, applied in areas of conflicts, was instrumental in adapting to the sudden shift to remote learning in March 2020. As founders of this virtual, civic engagement initiative between Hudson Valley undergraduates and stateless college students in Gaza, we set goals to work around warplane bombardments as well as electricity and Wi-Fi shortages in refugee spaces. Drawing upon our existing knowledge of applied intercultural communication competence, student-teacher global activism, and student-centered global advocacy in emergencies, we were able to identify pathways to rethinking the pedagogy of activism and social justice in distance learning. These same strengths aided us in swiftly adapting to a “new normal” during the worldwide pandemic, and now as we enter the post-pandemic world.

Further Reading

Lynk, Michael. “Gaza ‘unliveable,’ UN special rapporteur for the situation of human rights in the OPT tells third committee.” The United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine. October 24, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/unispal/document/gaza-unliveable-un-special-rapporteur-for-the-situation-of-human-rights-in-the-opt-tells-third-committee-press-release-excerpts/.

Thomas, Warren L. “Cross-Cultural Communication: Perspectives in Theory and Practice.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 49: 2006.

Works Cited

Abu Amer, Adnan. “How the Gaza War Affected Palestinian Politics.” Al Jazeera. June 7, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/6/7/gaza-war-leaves-its-mark-on-the-palestinian-political-system.

Azaiza, Mohammed. “The United Nations Was Right – Gaza Is Unlivable.” Haaretz, September 20, 2020. https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-the-united-nations-was-right-gaza-is-unlivable-1.9145175.

Berger, Miriam, and Hazem Balousha. “The U.N. Once Predicted Gaza Would Be ‘Uninhabitable’ by 2020. Two Million People Still Live There.” Washington Post, January 2, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/01/01/un-predicted-gaza-would-be-uninhabitable-by-heres-what-that-actually-means/.

Bureau of International Labor Affairs. Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – West Bank and the Gaza Strip. 2019. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/west-bank-and-gaza-strip.

Burton, David. “A Service Learning Rubric.” VCU Teaching. 1999.

“Gaza ‘Unliveable’, UN Special Rapporteur for the Situation of Human Rights in the OPT Tells Third Committee – Press Release (Excerpts).” Question of Palestine, https://www.un.org/unispal/document/gaza-unliveable-un-special-rapporteur-for-the-situation-of-human-rights-in-the-opt-tells-third-committee-press-release-excerpts/.

Hofstede, Geert, and Gert Jan Hofstede. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. McGraw-Hill. 2010.

“Israel/OPT: UN Experts Call on Israel to Ensure Equal Access to COVID-19 Vaccines for Palestinians.” OHCHR, January 14, 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/01/israelopt-un-experts-call-israel-ensure-equal-access-covid-19-vaccines.

Kim, Young Yun. “Communication and Cross-Cultural Adaptation: An Integrative Theory.” Multilingual Matters: 1988.

Macintyre, Donald. “By 2020, the UN Said Gaza Would Be Unliveable. Did It Turn out That Way?” The Guardian, December 28 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/28/gaza-strip-202-unliveable-un-report-did-it-turn-out-that-way.

Purser, Ronald. McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality. Repeater. 2019.

Schlein, Lisa. 2018. “UN Says Gaza Could Become Uninhabitable by 2020.” VOA, https://www.voanews.com/a/un-says-gaza-could-become-uninhabitable-by-2020/4569898.html.

Tawil-Souri, Helga, and Dina Matar. Gaza as Metaphor. Hurst. 2016.

Thomas, David R. “Understanding Cross-Cultural Communication.” South Pacific Journal of Psychology, vol. 7, ed 1994, pp. 2–8.

Trew, Bel. “Opinion: The UN Said Gaza Would Be Uninhabitable by 2020 – In Truth, It Already Is.” The Independent, December 30 2019, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/israel-palestine-gaza-hamas-protests-hospitals-who-un-a9263406.html.

Williams, Ursula J. “Encouraging Civic-Mindedness in the Undergraduate Chemistry Classroom.” Chemistry Student Success: A Field-Tested, Evidence-Based Guide, ACS Publications. 2020, pp. 103–17.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hajjaj, N. (2023). Global Cultural Exchange, Women’s Leadership, and Advocacy: Connecting the Hudson Valley and the Gaza Strip Through WhatsApp. In: Murray, B., Brill-Carlat, M., Höhn, M. (eds) Migration, Displacement, and Higher Education. Political Pedagogies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12350-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12350-4_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-12349-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-12350-4

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)