Abstract

The intergenerational transmission of socio-economic status is driven to a significant extent through parents with higher socio-economic status providing advantages to their children as they move through the education system. At the same time, attainment of higher education credentials constitutes an important pathway for upwards social mobility among individuals from low socio-economic family backgrounds. Given the critical importance of higher education for socio-economic outcomes of children, this chapter focuses on young people’s journeys into and out of university. Drawing on the life course approach and opportunity pluralism theory, we present a conceptual model of the university student life cycle that splits individuals’ higher education trajectories into three distinct stages: access, participation and post-participation. Using this model as a guiding framework, we present a body of recent Australian evidence on differences in pathways through the higher education system among individuals from low and high socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds. In doing so, we pay attention to factors such as family material circumstances, students’ school experiences and post-school plans, and parental education and expectations—all of which constitute important barriers to access, participation and successful transitions out of higher education for low SES students. Overall, our results indicate that socio-economic background plays a significant role in shaping outcomes at various points of individual’s educational trajectories. This is manifested by lower chances amongst low-SES individuals to access and participate in higher education, and to find satisfying and secure employment post-graduation. Our findings bear important implications for educational and social policy.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Educational inequalities are a critical area of policy concern in countries across the globe (OECD, 2017b), including Australia (Harvey et al., 2016b). In particular, the impacts of family background on educational outcomes—including access, participation, and post-graduation outcomes—have received considerable attention from both academics and policymakers (Tomaszewski et al., 2018). However, previous studies have often focused on a particular stage of the student life cycle, instead of approaching the issue through a more holistic lens. This chapter provides such a holistic perspective through leveraging the life course approach as an overarching framework.

Inequalities in higher education are particularly suited to be understood from a life course perspective, as they constitute the culmination of long-term processes of accumulation of advantage and disadvantage beginning at birth, or even prior to birth (Tomaszewski et al., 2018). Higher education is also a well-recognised mechanism for promoting intra-generational mobility, since university qualifications open the path to the most lucrative positions within the occupation structure (Desjardins & Lee, 2016; Heckman et al., 2016). In this chapter, we argue that inequalities in educational outcomes manifest across the key stages of a university student ‘life cycle’: the access, participation, and post-participation stages. We propose that, at each of these stages, individuals from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds will exhibit poorer outcomes than individuals from more socio-economically advantaged backgrounds. We link educational inequalities at each of these stages to indicators of family background that approximate different positions within the social hierarchy. This chapter focuses largely on one important status: the role of family socio-economic status (SES) commonly measured using parental occupational or educational status, or a composite measure of these.

Overall, it is well known that individuals born in low-SES families—however defined—are less likely to achieve positive outcomes, including participation and success in higher education and high labour-market returns to university qualifications. We know less, however, about how these differences come about, the mechanisms producing and reproducing them, the extent of such disparities at different points of the life course, and how we should intervene to ameliorate them. In this chapter, we showcase the value of the life course approach to understanding and intervening to resolve the persistence of educational inequalities at different stages of individuals’ educational careers. We also summarise recent empirical evidence taking a life course approach to enhance our appreciation of how socio-economic inequalities translate into differences in educational outcomes along different stages of university students’ life cycle. We conclude by pointing to policy implications and avenues for further research.

Inequalities in Higher Education from a Life Course Perspective

The life course approach is an increasingly influential lens through which researchers can study the intersections between socio-economic status and educational inequalities (Elder, 1995; Elder et al., 2003). As discussed in other chapters in this volume, this interdisciplinary research paradigm proposes principles to guide research on how relationships, life events and transitions, and social forces, influence people’s lives—including their educational outcomes—from birth to death (Elder, 1995). The role of time in producing and reproducing social inequalities is one of the central tenets of the life course approach. Broadly, this perspective highlights the importance of recognising ‘longitudinal dependencies’; that is, the influence of previous life events and experiences on later life outcomes. A toolset of theoretical principles follows from this general proposition, some of which are useful to understanding differences in higher-education access and participation by SES.

Unlike cross-sectional perspectives, where accumulation of disadvantage pertains to combinations of concurrent disadvantaged statuses, accumulation of disadvantage understood through the lens of life course theory refers to the recurrent experiences of disadvantage over time. Disadvantage is treated not as a static state, but rather as a cumulative process that unfolds over the life course (Elder et al., 2003). Compared to a one-off experience, repeated or chronic exposure to barriers and stressors can be more harmful to individuals’ chances to succeed in various aspects of their lives (Ferraro & Kelley-Moore, 2003; Kuh & Ben-Shlomo, 2004; Laub & Sampson, 1993; Sampson & Laub, 1996). Hence, individuals’ outcomes across life domains (including education) must be understood in the context of their earlier experiences in those and other domains. A related and important concept is that of individuals’ life course trajectories, defined as the sequences of events, transitions and social roles across multiple and interconnected life domains that individuals encounter as they age. Observing people at a single location within such trajectories is but a poor proxy for where they come from, and where they are heading.

In the context of this chapter, one could think of individual-specific trajectories capturing young people’s cumulative experiences and success, or lack of it, in the higher education system from entry (access to higher education) through participation, and onto exit (including post-graduation outcomes). These individual educational trajectories will be intertwined with those for other life domains, such as family or health trajectories. Individuals from low SES backgrounds experience greater exposure to stressors and barriers to educational success at multiple stages of the life course, which can result in educational trajectories that differ from those of those from more advantaged backgrounds.

Life course trajectories (including those pertaining to education) are not deterministic, and can be altered by life course experiences, including events and transitions. When negative, trajectories can be improved by individuals’ receipt of formal or informal support. In life course jargon, visible changes in the direction of a long-term developmental trajectory are referred to as turning points. Closely related to this notion are the concepts of sensitive and critical periods. Sensitive periods are periods within individuals’ life courses in which their outcomes are comparatively more likely to be affected, or affected more strongly, by a certain factor (e.g., the experience of adversity). Similarly, critical periods are those in which such exposures have lasting, even lifelong, consequences on individuals’ outcomes (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002). In addition, different factors may become important for individuals’ outcomes at different turning points of the life course. In the context of higher education, belonging to certain socio-economically disadvantaged groups may have different effects on the onset and maintenance of educational disadvantage at different points of the educational life course.

Opportunity Pluralism and ‘Bottlenecks’ to Success

Fishkin’s (2014) recent theory of opportunity pluralism offers additional insights into how educational inequality, including inequality in higher education, needs to be understood as a long-term process. Fishkin argues that the goal of Government policy should be to increase the range of opportunities available to individuals at all life stages, so that people can freely choose among different life paths leading to ‘human flourishing’. The pursuit and attainment of a university degree is a clear example of such a path. This argument resonates with the notion of ‘capability development’, coined by economist Amartya Sen, and its associations with social disadvantage (Sen, 1992).

Opportunity pluralism involves revising the ways in which we think about equality of opportunity by focusing on how opportunities in a society are created, distributed and controlled. Fishkin uses the analogy of ‘bottlenecks’ to refer to “the narrow places through which people must pass if they hope to reach a wide range of opportunities that fan out on the other side” (Fishkin, 2014, p. 1). In the context of this chapter, higher education is in itself a ‘bottleneck’, one that regulates access to labour market outcomes, social recognition and prestige, and other desirable socio-economic outcomes. However, earlier bottlenecks regulate individuals’ progress through the education system leading to higher education participation. These include: (i) Developmental bottlenecks—whereby certain developmental capacities are required to develop higher-order abilities (e.g., cognitive or non-cognitive skills necessary to do well at school); (ii) qualification bottlenecks—when a formal qualification or test score is required to gain access to the next set of opportunities (e.g., a pass mark in a university admission test); and (iii) instrumental-good bottlenecks—when some material good is required to attain a goal (e.g., money to fund one’s university studies).

Consistent with the life course principles outlined before, these educational bottlenecks are sequentially arranged and span from very early in life to the point of higher education entry (and beyond). As Chambers (2009) puts it “each outcome is another opportunity” (p. 374): access to later bottlenecks is contingent on successful passage through earlier ones, producing a concatenation of opportunities. For example, with some exceptions, young people typically face the opportunity to enter higher education if they have previously obtained a secondary school qualification, and only obtain such qualifications if they have developed the necessary cognitive skills. Critically, many of these opportunities are shaped by individuals’ socio-economic background, particularly at the earlier stages of the life course.

At the early stages of the life course, both genetic and socio-economic factors running though families affect children’s capacity to go through the first set of bottlenecks (Heckman, 2006; Kautz et al., 2014). The former include the child’s genetic endowments, while the latter include parental investments in the child, e.g., money, parenting practices, role modelling, etc. At this point, Fishkin’s thinking deviates from other perspectives emphasising the importance of early intervention—e.g., that of Nobel Prize awardee James Heckman. While Heckman advocates for intervening as early as possible to shift a disadvantaged life trajectory (within the first 5 years of life and prior to school entry), Fishkin argues that early intervention is never ‘early enough’ and thus not sufficient in isolation. In his words, “there is no fair place to put the starting gate” as “any starting gate will have the effect of amplifying past inequalities of opportunity” (Fishkin, 2014, p. 71). An alternative to early intervention may consist of early and sustained intervention over the life course: “instead of building a starting gate at one specific place, we have to do some of the work of addressing or mitigating inequalities at every stage” (Fishkin, 2014, p. 73). In addition, the necessity for certain bottlenecks should be questioned in the context of their consequences for structuring opportunities and life trajectories, such as the necessity of passing certain formal academic tests at specified ages.

Life Course Theory and Opportunity Pluralism in Practice: A Conceptual Model of the Student Life Cycle

Applying the life course approach and opportunity pluralism theory to inform our understandings of educational disadvantage in Australia hinges on the ability to identify the nature of the bottlenecks encountered by young people navigating the process. Recent efforts have provided some groundwork in this area in the context of higher education participation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2014). For example, research by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2014) proposed a model in which student higher education disadvantage was evaluated at four phases in the student life course: (i) the pre-entry phase (i.e., the decision about whether to apply to university), (ii) the enrolment phase (i.e., experiences navigating the admission process), (iii) the university experience phase (i.e., how well young people cope with participation in higher education), and (iv) the graduate outcomes phase (i.e., the post-graduation returns to education).

A similar model was suggested as part of the Critical Interventions Framework for advancing equity in Australian Higher Education by Naylor et al. (2013). The categorisation of equity initiatives contained in that framework was based on existing equity programs, such as outreach programs, many funded by the Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program (HEPPP), which is a testament to the fact that an understanding of the longitudinal nature of disadvantage in higher education has already been influencing higher education policies in Australia for some years. Consistent with existing outreach programs, the aforementioned models and associated evaluation frameworks consider the stage of school (including primary school) as the earliest point for interventions and evaluations relevant to higher education outcomes.

Pitman and Koshy’s (2014) framework for measuring equity performance in Australian Higher Education reflects an even stronger acknowledgement of the longitudinal nature of disadvantage in higher education. Their framework includes the domain of early childhood and proposes to report indicators from the Early Child Development Census and attendance rates at pre-school as part of the higher education equity performance reporting. The framework also covers student achievement indicators at primary and secondary school level, which could provide the basis for a more thorough examination of bottlenecks in the Australian education system, particularly as they pertain to the experiences of students from families of different socio-economic status.

Recent reports by the Centre for International Research on Education Systems (Lamb et al., 2015, 2020) adopt a similar perspective. They consider a conceptual model in which educational opportunities in the Australian context are channelled through four sequential milestones: (i) Developmental readiness at school entry, (ii) school performance in Year 7, (iii) completion of school Year 12 by age 19, and (iv) full engagement in education, training or work at age 24. Progress through these milestones constitutes a ‘leaking pipeline’ of sorts, with some students meeting the milestone and others dropping out of the race. This research provides important background and directions for the identification of ‘milestones’ and ‘bottlenecks’ in Australian youth’s pathways towards higher education (and beyond). The importance of considering longitudinal dependencies to study disadvantage in higher education is internationally recognised (OECD, 2017a, b) and apparent in the policy models in other countries, providing support that long-view solutions can work in practice.

The Three Phases of the Student Life Cycle: Access, Participation, and Post-participation

Informed by the body of work outlined above, in this chapter we conceptualise the pathways into and through higher education along three broad stages: access, participation and post-participation. Within each of these stages, we are interested in how socio-economic background shapes outcomes relevant to higher education.

In our framing, the ‘access’ stage comprises the ‘before university’ part of the student trajectory, including school experiences and performance. The key aspects to consider with respect to the access stage include the multiple barriers that individuals from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds may face in their journey to university. Previous literature identifies a range of such barriers, including material barriers (Edwards & McMillan, 2015; Lamb et al., 2004; Sellar & Gale, 2011), cognitive and non-cognitive barriers (Dickson et al., 2016; Harvey et al., 2016a; Kautz et al., 2014), aspirational barriers (Harvey et al., 2016a; James et al., 2008), cultural barriers (Bok, 2010; Burke et al., 2016; Devlin, 2013) and institutional barriers (Armstrong & Cairnduff, 2012). In this chapter, we present the results of empirical analyses in which we tested the relevance of selected barriers on the likelihood of university enrolment among young people from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

The ‘participation’ stage follows from the ‘access’ stage and refers to the time at university. The key areas of interest identified in the literature include issues of continued participation (attrition/retention) and completion of university studies. For instance, previous studies suggest that low SES students not only have a lower likelihood to enrol into university compared with their more socio-economically advantaged peers, but they are also less likely to continue and complete their studies once enrolled (Harvey et al., 2016a, b; Productivity Commission, 2019). In this chapter, we explore the influence of individual and family-level indicators of socio-economic background on the likelihood of university participation within the Australian context.

The ‘post-participation’ stage covers the time after university graduation and has been increasingly recognised in the literature as an integral stage when considering outcomes pertaining to higher education participation and success (Naylor et al., 2013; Tomaszewski et al., 2021). Completing a university degree has been associated with a number of positive outcomes spanning various life domains, including labour market participation (Heckman et al., 2016; OECD, 2019) and improved health and wellbeing (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2008; Heckman et al., 2017; Oreopoulos & Petronijevic, 2013). However, robust evidence on inequalities in these post-graduation outcomes by socio-economic background remains sparse. The analyses presented in this chapter afford us unique understandings of these processes.

In summary, this chapter aims to shed the light on how socio-economic background shapes differences in higher education outcomes at various stages of the student journey, including the mechanisms producing and reproducing these differences, and the extent to which such disparities emerge at various points of the university student life cycle. This evidence can in turn improve our understanding on how and when we should intervene to ameliorate socio-economic-background inequalities in higher education.

Socio-Economic Status Differences in Higher Education Access, Participation, and Outcomes: Empirical Evidence for Australia

The theoretical considerations and empirical evidence outlined earlier lead to the expectation that socio-economic disparities in family background may shape individuals’ outcomes at various stages of their journeys into and out of higher education. Validating and refining these theoretical propositions, however, requires a body of robust empirical evidence. In the remainder of this chapter, we identify and briefly summarise key findings from selected recent Australian studies relevant to the influence of socio-economic background on higher education outcomes at various points of the life course. These findings come from our long-standing program of research aimed at understanding how individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, including low socio-economic status, engage with the higher education system. The evidence presented here is based on robust, nationally representative longitudinal data for Australia, which improves on earlier cross-sectional studies based on a single point in time and longitudinal studies based on small and non-representative samples.

Over the next sections, we present empirical evidence from three studies covering the three stages distinguished in our conceptual model of student life cycle: access to higher education, participation in higher education, and post-participation outcomes. First, we present evidence on the influence of various barriers to accessing university faced by young people at the cusp of making the transition out of school (at approximately 15 years of age). We then move onto exploring how various individual and family-level markers of socio-economic disadvantage shape the chances of university participation several years later, at the ages of around 18–22 years. Finally, we present empirical evidence on how socio-economic family background shapes a range of post-graduation outcomes spanning up to 15 years after obtaining a university degree.

Access to Higher Education: Uneven Barriers to University Enrolment by Socio-Economic Background

We start our presentation of empirical evidence by showcasing a recent analysis pertaining to the access to university stage, focusing on the relevance of various barriers to university enrolment among low and high SES students. The analysis leverages data from the 2006 Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY). LSAY was designed to study transitions from school to further education, work and other destinations, following cohorts of students aged 15 years and tracking them over a 10-year period. The survey allows longitudinal tracking of post-school outcomes, while capturing information on a range of individual and family characteristics, including markers of disadvantage and potential barriers to participating and succeeding in higher education. The analyses presented in this chapter were based on the 2006 LSAY cohort, which tracks a cohort of young people aged 15 in 2006 up until 2015. The key variables representing various barriers to university participation were captured at LSAY Wave 1, when the individuals were approximately 15 years old.

Before we start discussing the specific barriers to accessing university among low SES youth, it is useful to present an overall picture of the socio-economic disparities in the likelihood of university enrolment over time. Figure 7.1 shows the likelihood of enrolling into university for young people from low and high SES backgrounds based on the LSAY 2006 data. It is evident that young people start enrolling into university between Waves 3 and 4 (at about 18–19 years of age), and already at that point a slightly larger proportion of young people from high SES backgrounds do so, compared with their peers from low SES backgrounds. However, the socio-economic background gap in enrolment becomes larger by Wave 5 (at approximately 20 years of age). At this point, about 50% of young people from high socio-economic status backgrounds have already enrolled at university, compared with just over 20% of young people from low SES backgrounds. This university enrolment gap remains fairly constant up to the end of the observation period (Wave 11; age approximately 25). By then, around 60% of young people from higher socio-economic backgrounds and about 30% of young people from low socio-economic status backgrounds were observed to have enrolled into university. Hence, we find a large socio-economic status gap in university enrolment, one which emerges largely due to differential enrolment rates at a “standard” enrolment time (i.e., ages 18–19).

Proportion of students enrolling into university, by socio-economic background

Notes: Kaplan-Meier (A Kaplan Meier graph was chosen to visualise the gap between the two groups and as such is the preferred approach than a life table) hazard rates, replicating analyses included in Tomaszewski et al. (2017) updated with LSAY 2006 data. Source: LSAY 2006 sample (n = 14,170)

The available literature identifies various mechanisms that help explain the socio-economic status differences in university enrolment. Material barriers to accessing higher education relate to a lack of financial resources, which can compromise the ability of families or individuals to invest in education, including higher education (Sellar & Gale, 2011; Edwards & McMillan, 2015). Cognitive barriers to higher education involve multiple dimensions but have been approximated in the empirical literature by measures of school performance. In Australia, poor school performance has been recognised as a major barrier to accessing university for people from low SES backgrounds (Harvey et al., 2016a; James et al., 2008). Non-cognitive barriers refer to lack of non-cognitive skills, such as perseverance (“grit”), conscientiousness, self-control, trust, attentiveness, self-esteem and self-efficacy, resilience to adversity, openness to new experiences, empathy, humility, or tolerance of diverse opinions (Kautz et al., 2014). Barriers related to aspirations and expectations for university participation have been another major focus of research and intervention in Australia in relation to people from low SES backgrounds (Bennett et al., 2015; Gale & Parker, 2018).Footnote 1 Cultural factors are another kind of potential barrier to accessing university. Some authors see universities as reproducing, valuing and relying upon particular cultural views and practices concerning ways of speaking, thinking and behaving, which can manifest as barriers for those socialised into different social and cultural worlds (Devlin, 2013). Relatedly, institutional barriers to accessing university refer to the barriers embedded in the structures and characteristics of schools and universities, and their associated practices (Armstrong & Cairnduff, 2012).

Figure 7.2 illustrates examples of such barriers with empirical data based on our research. The figure shows how various barriers to university participation that could be identified in LSAY are associated with a lower propensity to enrol into university (for both low and higher socio-economic status students).

Selected barriers to university enrolment

Notes: Hazard ratios from a Cox regression model (Cox regression models are semi-parametric regression techniques of the event-history family, which are useful to determine how different factors influence the occurrence of an event over time (Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, 2004). In the context of higher education research, event history models are commonplace in studies of university student retention/dropout (Bahi et al., 2015; Gury, 2011; Vallejos & Steel, 2017) and time to degree completion (Lassibille & Gómez, 2011; Wao, 2010). They have also been used to examine routes to University amongst non-traditional students (Brändle, 2017) and returns to University after intermissions (Johnson, 2006)) adjusted for gender, Indigenous status, school location and non-English speaking background (NESB), based on analyses included in Tomaszewski et al. (2018). Variables capturing barriers to university participation recorded at Wave 1. University enrolment measured across Waves 2–10. Source: LSAY 2006 sample (n = 9326)

Next, we demonstrate that these common barriers to accessing university are more likely to occur among young people from low socio-economic status backgrounds. Figure 7.3 shows that the likelihood of experiencing these different barriers to university participation is significantly higher among people from low socio-economic status backgrounds, relative to their more advantaged peers. The results confirm that low socio-economic status is consistently associated with increased chances of experiencing the barriers to higher education participation. For example, the odds of low socio-economic status students having low PISA math scores were almost 3 times greater than those of students from more advantaged backgrounds, while the odds of attending a low socio-economic status school or receiving financial support in the form of youth allowance were even higher—around 4 times greater than those of students from more advantaged backgrounds.

Propensity to experience barriers to higher education participation by socio-economic background

Notes: Odds ratios from logistic regression model adjusted for gender, Indigenous status, school location and non-English speaking background (NESB), based on analyses included in Tomaszewski et al. (2018). All ORs are statistically significant in relation to the reference category (higher SES students) at p < 0.005. Variables capturing barriers to university participation and SES recorded at Wave 1 and Wave 2. Source: LSAY 2006 sample (n = 9326)

Socio-Economic Background and Higher Education Participation: Contributions of Individual- and Area-Level Factors

Previous research demonstrates that, compared with their more socio-economically advantaged peers, low socio-economic status students not only have a lower likelihood to enrol into university, but are also less likely to continue their studies once enrolled (Harvey et al., 2016b; Productivity Commission, 2019). While the lower likelihood of higher education participation among low socio-economic status students is a well-established finding, a number of research gaps remain. These include the concrete factors that may be driving continuing participation among disadvantaged students. Specifically, one of the questions that remains unanswered is the relative influence of markers of socio-economic advantage or disadvantage operating at various levels (e.g., the individual, area, or school level).

This section of the chapter presents the results of our recent research aiming to address this question though leveraging data from the Australian Census Longitudinal Dataset (ACLD). Specifically, data from the ACLD 2011–2016 (ABS, 2018) panel were used to investigate university participation for people growing up in disadvantaged areas. We capture university participation at the ages of 18–22 and relate that to the data on socio-economic disadvantage captured 5 years earlier, when the young people were aged 13–17 and most of them still lived with their parents.

The empirical analysis presented here focuses on demonstrating the relevance of different aspects of socio-economic advantage and disadvantage captured at the individual-, local-area and school-sector levels to university participation. The individual-level markers of socio-economic disadvantage include an indicator for a university degree in the family (to approximate the relative disadvantage of being the ‘first in the family’ to attend university) and the information on the occupation of the male parent. Area-based indicators include an indicator of the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) Index of Education and Occupation (IEO) score of the postcode area of a student’s permanent address, which has been a measure commonly applied to monitor socio-economic disadvantage in higher education in Australia.Footnote 2 We capture area disadvantage using deciles, with the lowest, most disadvantaged SEIFA decile 1 as the reference category. We further include a measure of area remoteness, which constitutes a separate dimension of area-level disadvantage (Burnheim & Harvey, 2016). Furthermore, we also include information on the school sector (Government, Catholic and Other Non-Government) that the young person attended in 2011. The systemic role of the school system in maintaining or generating disadvantage in higher education participation has been a topic of considerable debate in Australia (Goss et al., 2016; James et al., 2004; McConney & Perry, 2010) and elsewhere (Hanselman, 2018; Hauser et al., 1976; OECD, 2010; Van de Werfhorst & Mijs, 2010). Figure 7.4 shows the likelihood of participating in higher education depending on these individual-level, area-level and school-level indicators.

Association between university participation and selected individual, area, and school characteristics

Notes: Odds ratios from multiple logistic regression adjusted based on analyses included in Tomaszewski et al. (2018). All ORs are statistically significant in relation to the reference category at p < 0.01. People not attending secondary school in 2011 were excluded from the model. Source: Australian Census Longitudinal Dataset, 2011–2016, data extracted using TableBuilder in June 2018

The results confirm the relevance of individual-level, area-based and school-level indicators of socio-economic status for university participation. Specifically, the chances of participating in higher education decrease with residence in each lower SEIFA decile, as indicated by the increasing magnitude of the odds ratios (which are all greater than 1) in relation to the reference category. Similarly, students from regional and remote areas are less likely to participate in higher education within the 5-year period, compared with students from major cities. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that the added individual-level markers exert an independent statistical effect on the probability of university participation. For example, secondary school students aged 13–17 years in 2011 had more than twice the odds of participating in higher education within 5 years when someone in their family had a degree in 2011 (ORs >2). Similarly, there are independent effects of the father’s occupation, and the type of school they attended in 2011, with students attending Independent or Catholic schools more likely to subsequently participate in higher education.

Taken together, the results suggest the independent effects of multiple individual-level, area-level and school-level markers of socio-economic advantage and disadvantage (parental occupation, ‘first in family’, SEIFA IEO scores, type of school, and area remoteness) on the likelihood of participation in higher education over the next 5 years. Each of these markers has its own independent statistical effect on the probability of university participation.

Beyond Graduation: Long-Term Impacts of Socio-Economic Background on Students’ Post-Graduation Outcomes

Research has consistently demonstrated that university education has positive impacts on individual outcomes. For instance, only 7% of university-educated adults aged 25–34 years are unemployed across OECD countries, compared to 9% of those with upper-secondary or post-secondary education, and 17% of those with lower qualifications (OECD, 2017a). Data for Australia also shows that employment rates are substantially higher for individuals holding postgraduate (82%) and bachelor (80%) degrees, compared with individuals without post-school qualifications (54%) (ABS, 2017). Furthermore, university graduates in Australia and internationally are also more likely to work in more prestigious occupations and earn higher wages (Card, 1999; Cassells et al., 2012; Daly et al., 2015; Desjardins & Lee, 2016; Heckman et al., 2016). The positive effects of higher education qualifications are not limited to the labour market, with research documenting influences across a range of other domains, including, general health (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2008), mental health (Heckman et al., 2017) and subjective wellbeing (Oreopoulos & Petronijevic, 2013; Oreopoulos & Salvanes, 2011). However, few studies have explicitly considered differences in these impacts by socio-economic background of the graduates. The scarce studies that explicitly consider socio-economic differences among graduates, tend to focus on short-term post-graduation outcomes, often due to limited data over long-run trajectories, and only consider labour market outcomes.

Internationally, Hansen (2001) reported higher economic returns to a university degree in Norway for high socio-economic status graduates than for low socio-economic status graduates, net of qualification level and field of study. Similarly, graduates in Norway, Italy and Spain whose parents had university qualifications were shown to be more likely to attain a high-status occupation 5 years after graduation, compared with similar graduates whose parents did not hold university qualifications (Triventi, 2013). Furthermore, a study analysing the effect of parental education on German and British university graduates’ occupational outcomes at the point of entry into the labour market, and 5 years after graduation showed that high socio-economic status individuals had a relative advantage over low socio-economic status graduates in securing high-status occupations (Jacob et al., 2015). However, the effect at the point of entry into the labour market was stronger than 5 years after graduation, suggesting a weakening of the socio-economic status gradient over time.

The limited Australian research in this area provides mixed evidence. For instance, Richardson et al. (2016) showed that low socio-economic status graduates were less likely to be employed 6 months after graduation, compared with high socio-economic status graduates. However, Li et al. (2017) reported no significant differences in employment rates between low and high socio-economic status graduates. Taking a longer perspective, Edwards and Coates (2011) demonstrated that low and high socio-economic status graduates had similar rates of employment and employment in a high-status occupation and median annual salaries 5 years after completing their university studies.

This part of the chapter presents recent empirical evidence drawing on our analysis of longitudinal data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The analysis aims to examine post-university trajectories of low socio-economic status and high socio-economic status graduates over a long run (up to 10 years post-graduation), capturing outcomes across multiple domains, including those that extend beyond indicators of labour-market performance.

HILDA is an annual household panel survey following a sample of individuals aged 15 and older over time. The HILDA Survey sample is largely representative of the Australian population in 2001 (Watson & Wooden, 2012). Data are collected using a complex, multi-stage sampling strategy at the household level, and a mixture of self-complete questionnaires and computer-assisted face-to-face interviews. In the empirical analyses summarised below, we use the first 16 Waves of the HILDA data, covering years 2001 to 2016. We use these data to construct an analytic sample of individuals who were observed at least twice and obtained a Bachelor’s degree during the life of the panel. In order to examine trends in outcomes post-graduation, we only include observations subsequent to individuals obtaining their degrees. We apply growth curve models to estimate the trajectories of post-graduation outcomes for individuals from low socio-economic status and high socio-economic status backgrounds. In this analysis, high socio-economic status graduates are defined as those with at least one parent in a professional or managerial occupation, and low socio-economic status as those where none of the parents are in a professional or managerial occupation.

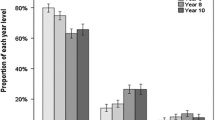

We focus the analyses on four outcome variables spanning labour-market circumstances, health and wellbeing (Fig. 7.5). Specifically, we model:

-

Hourly wages, log transformed to correct for a right-skewed distribution and adjusted to 2016 prices using the Consumer Price Index;

-

Job-security satisfaction determined from a question asking participants about their satisfaction with job security on a scale from 0 [totally dissatisfied] to 10 [totally satisfied];

-

Mental health captured using the mental health subscale of the SF-36, a 5-item additive scale with transformed scores ranging from 0 to 100 (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992); and

-

Financial prosperity, derived from a question asking participants to rate their “prosperity given current needs and financial responsibilities” using the following response options: 1 = Prosperous, 2 = Very comfortable, 3 = Reasonably comfortable, 4 = Just getting along, 5 = Poor and 6 = Very poor.

Selected outcome trajectories for university graduates from low and high SES backgrounds

Notes: Marginal effects from growth-curve models. Covariates held at their means and random effects at zero. Whiskers denote 90% confidence intervals. Source: HILDA Survey (2001–2016). Originally published in Tomaszewski et al. (2021)

The results show that hourly wages and financial prosperity increase with time since graduation for all graduates, while mental health and job-security satisfaction remain stable over time. The picture is somewhat mixed in relation to differences in outcomes by SES. The hourly wages and mental health of low socio-economic status graduates appear to be on par with those of high SES graduates throughout the observation period, that is, no differences between low socio-economic status and high socio-economic status graduates is detected. However, low socio-economic status graduates (red lines) have lower job-security satisfaction and financial prosperity in the first 4 years post-graduation, compared with high socio-economic status graduates (blue lines). These initial differences are statistically significant, as can be inferred from non-overlapping 90% confidence intervals. Subsequently, the trajectories of low and high socio-economic status graduates on these outcomes converge over time. That is, there is evidence of a ‘catch up’ effect for low socio-economic status graduates, which results in the outcomes comparable to those of high socio-economic status backgrounds towards the end of the observation period. Still, it takes a relatively long time—at least 4–5 years after graduation—for the average low socio-economic status graduate to achieve outcomes comparable to the average high socio-economic status graduate.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this chapter, we used a conceptual model of the university student life cycle as an organising framework to present a body of recent Australian evidence on differences in pathways through the higher education system among individuals from low and high socio-economic status backgrounds. The model introduced in the chapter splits individuals’ higher education trajectories into three distinct stages: access, participation and post-participation, with empirical evidence presented for each of these stages on the factors influencing the outcomes of people from low socio-economic status backgrounds. To do so, we leveraged three flagship longitudinal data sources for Australia: the Longitudinal Survey of Australian Youth (LSAY), the Australian Census Longitudinal Dataset (ACLD), and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey.

At the access stage, we used the 2006 LSAY data to investigate the relevance of various barriers to university enrolment identified in previous literature. This analysis demonstrated large gaps in university enrolment by socio-economic status, and confirmed the relevance of various barriers, including material, cognitive, non-cognitive, aspirational, cultural and institutional barriers, to accessing higher education. We further show that these barriers disproportionately manifest among low socio-economic status students at the age of 15, compared to their high socio-economic status peers. At the participation stage, we focused on the relative influence of various markers of socio-economic advantage or disadvantage operating at various levels: the individual, area and school levels. We used ACLD data to demonstrate that socio-economic disadvantage at all these levels matters for university participation at the age of 18–22. At the post-participation stage, we leveraged the HILDA Survey data to assess the differences in post-university outcomes for graduates from low socio-economic status and high socio-economic status backgrounds. We evaluated outcomes spanning the domains of work and health, demonstrating that the effects of socio-economic background extend beyond graduation—at least for some of the outcomes. While we find some evidence of a ‘catch up’ effect for low socio-economic status graduates, it does take them several years to achieve outcomes that are on par with those of their high socio-economic status peers.

The findings collated throughout this chapter bear important implications for educational and social policy. Overall, they suggest that, in contemporary Australia, socio-economic background continues to play a role in shaping outcomes at various points of individual’s educational trajectories. This is manifested by the lower chances that low socio-economic status individuals have to access and participate in higher education, and to find satisfying and secure employment in the first few years post-graduation. Specific findings presented in this chapter point to the presence of various barriers to accessing university, which is already evident among secondary school low socio-economic status students. This finding underscores the need for early intervention to align educational opportunities and trajectories experienced by low socio-economic status students with those of their high socio-economic status peers. For such barriers not to manifest at the age of 15, much earlier interventions—most likely starting in primary school—are required. Further, our analyses demonstrated the presence of multiple barriers that span various domains and dimensions of disadvantage, consistent with the life course principle of interdependence of life domains. This piece of evidence indicates that any interventions must be multi-pronged—focusing on an array of needs, instead of prioritising a single dimension (such as material disadvantage). Further, our analyses of individual-, area- and school-level factors influencing university participation highlight the importance of developing such interventions with attention to particular context—geographical, school and community context. Moreover, because our analyses demonstrate that socio-economic disadvantage across various levels has independent effects on educational outcomes of young people, interventions should ideally be designed to be simultaneously delivered across multiple levels, for instance targeting individual, schools and communities at the same time. Finally, the evidence showing that socio-economic disadvantage extends to the post-graduation stage makes a stronger case for the importance of sustained interventions—even if we do intervene early, many low socio-economic status people will require additional support down the track.

Our research also points to avenues for further research. For instance, we note opportunities to further strengthen the evidence base in this space by leveraging administrative data covering whole populations, rather than large samples from these populations. Only with these data we will be able to estimate more precisely the extent of educational and socio-economic disadvantage, particularly for smaller and vulnerable groups (e.g., Indigenous students or students from refugee backgrounds) (Perales, 2021). Second, we are only able to present a ‘piece-meal’ picture of how student life cycles differ for low and high socio-economic status individuals. As fit-for-purpose data become available, future studies could attempt to track the same individuals over the full course of their student life cycle—from pre-school and school, through university, and beyond. Again, emerging administrative datasets offer distinct opportunities to accomplish this. Such a holistic analysis would also enable more comprehensive engagement with key concepts pertaining to the life course approach, such as consideration of longer-term trajectories, turning points, sensitive and critical periods, and sequences of transitions across multiple statuses.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

The SEIFA IEO combines census data on occupational and educational characteristics of individuals living within communities into a composite index to rank geographic areas. The resulting index is then assigned to individuals living in a given postcode area. Postcodes falling in the bottom 25% of the population aged 15–64 are categorised as low SES in official higher education equity reporting.

References

ABS. (2017, May). Education and work, Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/70E972E1E13FE089CA2581CD000C41D8?opendocument

ABS. (2018). Microdata: Australian census longitudinal dataset, 2011–2016 (2080.0). Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2080.0

Armstrong, D., & Cairnduff, A. (2012). Inclusion in higher education: Issues in university–school partnership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(9), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.636235

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2014). Towards a performance measurement framework for equity in higher education. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Bahi, S., Higgins, D., & Staley, P. (2015). A time hazard analysis of student persistence: A US university undergraduate mathematics major experience. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 13(5), 1139–1160.

Bennett, A., Naylor, R., Mellor, K., Brett, M., Gore, J., Harvey, A., Munn, B., James, R., Smith, M., & Whitty, G. (2015). The critical interventions framework part 2: Equity initiatives in Australian higher education: A review of evidence of impact. Funded by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Education and Training under the Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program.

Ben-Shlomo, Y., & Kuh, D. (2002). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(2), 285–293.

Bok, J. (2010). The capacity to aspire to higher education: ‘It’s like making them do a play without a script’. Critical Studies in Education, 51(2), 163–178.

Box-Steffensmeier, J., & Jones, B. (2004). Event history modelling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

Brändle, T. (2017). How availability of capital affects the timing of enrollment: The routes to university of traditional and non-traditional students. Studies in Higher Education, 42(12), 2229–2249.

Burnheim, C., & Harvey, A. (2016). Far from the studying crowd? Regional and remote students in Higher Education. In A. Harvey, C. Burnheim, & M. Brett (Eds.), Student equity in australian higher education: Twenty-five years of A Fair Chance For All. Springer: Singapore, pp. 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0315-8_1.

Burke, P. J. (2012). The right to higher education: Beyond widening participation. Routledge.

Burke, P. J., Bennett, A., Burgess, C., Gray, K., & Southgate, E. (2016). Capability, belonging and equity in higher education: Developing inclusive approaches. Centre of Excellence for Equity in Higher Education.

Card, D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1801–1863). Elsevier.

Cassells, R., Duncan, A., Abello, A., D’Souza, G., & Nepal, B. (2012). Smart Australians: Education and innovation in Australia. AMP.

Chambers, C. (2009). Each outcome is another opportunity: Problems with the moment of equal opportunity. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 8(4), 374–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X09343066

Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2008). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. In S. H. James, R. F. Schoeni, G. A. Kaplan, & H. Pollack (Eds.), Making Americans healthier: Social and economic policy as health policy. Russell Sage Foundation.

Daly, A., Lewis, P., Corliss, M., & Heaslip, T. (2015). The private rate of return to a university degree in Australia. Australian Journal of Education, 59(1), 97–112.

Desjardins, R., & Lee, J. (2016). Earnings and employment benefits of adult higher education in comparative perspective: Evidence based on the OECD survey of adult skills (PIAAC). UCLA. https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt0jz0k1pp/qt0jz0k1pp.pdf

Devlin, M. (2013). Bridging socio-cultural incongruity: Conceptualising the success of students from low socio-economic status backgrounds in Australian higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(6), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.613991

Dickson, M., Gregg, P., & Robinson, H. (2016). Early, late or never? When does parental education impact child outcomes? The Economic Journal, 126(596), F184–F231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12356

Edwards, D., & Coates, H. (2011). Monitoring the pathways and outcomes of people from disadvantaged backgrounds and graduate groups. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(2), 151–163.

Edwards, D., & McMillan, J. (2015). Completing university in a growing sector: Is equity an issue? Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER).

Elder, G. H. J. (1995). The life course paradigm: Social change and inidvidual development. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder Jr., & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 101–139). American Psychological Association.

Elder, G. H. J., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–22). Kluwer.

Ferraro, K. F., & Kelley-Moore, J. A. (2003). Cumulative disadvantage and health: Long-term consequences of obesity? American Sociological Review, 68(5), 707.

Fishkin, J. (2014). Bottlenecks: A new theory of equal opportunity. Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/bottlenecks-9780199812141?cc=au&lang=en&

Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2018). Student aspiration and transition as capabilities for navigating education systems. In A. Tarabini & N. Ingram (Eds.), Educational choices, transitions and aspirations in Europe (pp. 32–49). Routledge.

Goss, P., Sonnemann, J., Chisholm, C., & Nelson, L. (2016). Widening gaps: What NAPLAN tells us about student progress. Grattan Institute.

Gury, N. (2011). Dropping out of higher education in France: A micro-economic approach using survival analysis. Education Economics, 19(1), 51–64.

Hanselman, P. (2018). Do School learning opportunities compound or compensate for background inequalities? Evidence from the case of assignment to effective teachers. Sociology of Education, 91(2), 132–158.

Hansen, M. N. (2001). Education and economic rewards. Variations by social-class origin and income measures. European Sociological Review, 17(3), 209–231.

Harvey, A., Andrewartha, L., & Burnheim, C. (2016a). Out of reach? University for People from low socio-economic status backgrounds. In A. Harvey, C. Burnheim, & M. Brett (Eds.), Student equity in Australian higher education: Twenty-five years of a fair chance for all (pp. 69–85). Springer Singapore). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0315-8

Harvey, A., Burnheim, C., & Brett, M. (Eds.). (2016b). Student equity in Australian higher education: Twenty-five years of a fair chance for all. Springer.

Hauser, R. M., Sewell, W. H., & Alwin, D. F. (1976). High school effects on achievement. In W. Sewell, R. M. Hauser, & D. Featherman (Eds.), Schooling and achievement in American society (pp. 309–341). Academic.

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900–1902. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/312/5782/1900.full

Heckman, J. J., Humphries, J. E., & Veramendi, G. (2016). Returns to education: The causal effects of education on earnings, health and smoking. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heckman, J. J., Humphries, J. E., & Veramendi, G. (2017). The non-market benefits of education and ability. IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Jacob, M., Klein, M., & Iannelli, C. (2015). The impact of social origin on graduates’ early occupational destinations—An Anglo-German comparison. European Sociological Review, 31(4), 460–476.

James, R., Baldwin, G., Coates, H., Krause, K., & McInnis, C. (2004). Analysis of equity groups in higher education 1991–2002. Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne.

James, R., Bexley, E., Anderson, A., Devlin, M., Garnett, R., Marginson, S., & Maxwell, L. (2008). Participation and equity: A review of the participation in higher education of people from low socioeconomic backgrounds and indigenous people. Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne.

Johnson, I. Y. (2006). Analysis of stopout behavior at a public research university: The multi-spell discrete-time approach. Research in Higher Education, 47(8), 905–934.

Kautz, T., Heckman, J. J., Diris, R., Weel, B. T., & Borghans, L. (2014). Fostering and measuring skills: Improving cognitive and non-cognitive skills to promote lifetime success. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxsr7vr78f7-en

Kuh, D., & Ben-Shlomo, Y. (Eds.). (2004). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Lamb, S., Walstab, A., Teese, R., Vickers, M., & Rumberger, R. (2004). Staying on at school: Improving student retention in Australia (Report for the Queensland Department of Education and the Arts). Centre for Post-compulsory Education and Lifelong Learning, The University of Melbourne.

Lamb, S., Jackson, J., Walstab, A., & Huo, S. (2015). Educational opportunity in Australia 2015: Who succeeds and who misses out. Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University, for the Mitchell Institute

Lamb, S., Huo, S., Walstab, A., Wade, A., Maire, Q., Doecke, E., Jackson, J., & Endekov, Z. (2020). Educational opportunity in Australia 2020: Who succeeds and who misses out. Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University, for the Mitchell Institute.

Lassibille, G., & Navarro Gómez, M. L. (2011). How long does it take to earn a higher education degree in Spain? Research in Higher Education, 52(1), 63–80.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (1993). Turning points in the life course: Why change matters to the study of crime. Criminology, 31(3), 301–325.

Li, I. W., Mahuteau, S., Dockery, A. M., & Junankar, P. N. (2017). Equity in higher education and graduate labour market outcomes in Australia. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(6), 625–641.

McConney, A., & Perry, L. B. (2010). Science and mathematics achievement in Australia: The role of school socioeconomic composition in educational equity and effectiveness. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 8(3), 429–452.

Naylor, R., Baik, C., & James, R. (2013). A critical interventions framework for advancing equity in Australian higher education: Report prepared for the department of industry, innovation, climate change, science, research and tertiary education. Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne.

OECD. (2010). PISA 2009 results: What makes a school successful? – Resources, policies and practices (Vol. IV). OECD.

OECD. (2017a). Education at a Glance 2017: OECD indicators. Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/eag-2017-en.pdf?expires=1523431013&id=id&accname=ocid177546&checksum=E5D651D61AAC7CDE842778117CEB7684

OECD. (2017b). Educational opportunity for all: Overcoming inequality throughout the life course. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264287457-en

OECD. (2019). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD.

Oreopoulos, P., & Petronijevic, U. (2013). Making college worth it: A review of the returns to higher education. The Future of Children, 23(1), 41–65.

Oreopoulos, P., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1), 159–184.

Perales, F. (2021). The road less travelled: Using administrative data to understand inequalities by sexual orientation. Law in Context, 7, 74–87.

Pitman, T., & Koshy, P. (2014). A framework for measuring equity performance in Australian higher education: Draft framework document V1.6. National centre for student equity in higher education, .

Productivity Commission. (2019). The demand driven university system: A mixed report Card. The Productivity Commission..

Richardson, S., Bennett, D., & Roberts, L. (2016). Investigating the relationship between equity and graduate outcomes in Australia. The National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education at Curtin University.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1996). Socioeconomic achievement in the life course of disadvantaged men: Military service as a turning point, circa 1940–1965. American Sociological Review, 61(3), 347–367.

Sellar, S. (2013). Equity, markets and the politics of aspiration in Australian higher education. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 34(2), 245–258.

Sellar, S., & Gale, T. (2011). Mobility, aspiration, voice: A new structure of feeling for student equity in higher education. Critical Studies in Education, 52(2), 115–134.

Sellar, S., & Storan, J. (2013). ‘There was something about aspiration’: Widening participation policy affects in England and Australia. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 19(2), 45–65.

Sellar, S., Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2011). Appreciating aspirations in Australian higher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764x.2010.549457

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Clarendon Press.

Tomaszewski, W., Perales, F., & Xiang, N. (2017). Career guidance, school experiences and the university participation of young people from low socio-economic backgrounds. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 11–23.

Tomaszewski, W., Kubler, M., Perales, F., Western, M., Rampino, T., & Xiang, N. (2018). Review of identified equity groups. ISSR, UQ submitted to the Australian Department of Education and Training.

Tomaszewski, W., Perales, F., Xiang, N., & Kubler, M. (2021). Beyond graduation: Socio-economic background and post-university outcomes of Australian graduates. Research in Higher Education, 62, 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09578-4

Triventi, M. (2013). The role of higher education stratification in the reproduction of social inequality in the labor market. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 32, 45–63.

Vallejos, C. A., & Steel, M. F. (2017). Bayesian survival modelling of university outcomes. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 180(2), 613–631.

Van de Werfhorst, H. G., & Mijs, J. J. B. (2010). Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: A comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 407–428.

Wao, H. O. (2010). Time to the doctorate: Multilevel discrete-time hazard analysis. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 22(3), 227–247.

Ware, J. E., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2012). The HILDA survey: A case study in the design and development of a successful household panel survey. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 3(3), 369–381.

Acknowledgements

Parts of the chapter are based on materials included in Tomaszewski et al. (2018), which was funded by the Australian Department of Education and Training. Parts of the chapter also draw on materials published in Tomaszewski et al. (2021), which was supported from a grant by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tomaszewski, W., Perales, F., Xiang, N., Kubler, M. (2022). Differences in Higher Education Access, Participation and Outcomes by Socioeconomic Background: A Life Course Perspective. In: Baxter, J., Lam, J., Povey, J., Lee, R., Zubrick, S.R. (eds) Family Dynamics over the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-12223-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-12224-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)