Abstract

Adolescence is a time when developmental and contextual transitions converge, increasing the risk for adverse outcomes across the life course. It is during this period that self-concept declines, mental health problems increase and when young people make educational and occupational plans for their future. Considerable research has shown that parent engagement in their child’s learning has positive effects on academic and wellbeing outcomes and may be a protective factor in adolescence. However, it is during adolescence that parent engagement typically declines. Most studies focus on early childhood or use cross-sectional designs that do not account for the high variability in both the child’s development and the parent-child relationship over time. In this chapter, we examine the association between parent engagement and students’ outcomes—self-concept, mental health, and educational aspirations—drawing on national data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, while accounting for the school context—school belonging, peer connection problems, and bullying—and parenting styles using panel fixed effects models. We then explore perceptions of parental engagement and educational aspirations among a sample of adolescent students from highly disadvantaged backgrounds using interviews from the Learning through COVID-19 study. Findings show that parent engagement is important for students’ outcomes such as self-concept, mental health and aspirations in early and middle adolescence, even when accounting for family and school context factors. Further, parent engagement in late adolescence, with students from highly disadvantaged backgrounds, continues to be important for positive student outcomes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Deep and persistent disadvantage in the educational outcomes of students continues to concern developed nations such as Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom (Brownstein, 2016; Thomson, 2013; Weale, 2016; Wilson et al., 2015). Students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to underachieve in school and face an elevated risk for a variety of adverse outcomes across their life course such as delinquent activity and offending, substance misuse, social exclusion and isolation, early parenthood, mental health illnesses, and underemployment (Hatch et al., 2007; Henry & Huizinga, 2007a, b; OECD, 2013; Rocque et al., 2017; Stranger, 2002). In this chapter we apply the life course principle of ‘linked lives’ to investigate how parents’ engagement in their adolescent child’s education and the school environment are related to mental health, specifically anxiety and depression, self-concept, and educational expectations. We draw on data from a general population study and qualitative interviews to explore the interconnected nature of parents, schools, and socio-economic context in influencing adolescents’ aspirations and psychological wellbeing across early, middle, and late adolescence.

Background

There is considerable evidence that parent engagement in their child’s learning has positive effects on student achievement (Benner et al., 2016; Castro et al., 2015; Hill & Tyson, 2009). Parent engagement may be defined as the engagement of parents or primary carers in education-related activities that are expected to foster academic achievement and the social and emotional wellbeing of children (Fishel & Ramirez, 2005). Parent engagement is a multidimensional construct including home-based parent engagement, school-based parent-engagement and academic socialisation (Epstein & Sanders, 2002a, b; Fan & Chen, 2001; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994; Hill & Tyson, 2009; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014). School-based engagement includes drawing on parent expertise and two-way communication with teachers. Home-based engagement includes assisting with schoolwork and fostering other learning opportunities in everyday activities. Academic socialisation is the process through which parents’ foster high educational aspirations and expectations in their child. It involves communicating the importance and value of education (including showing interest in their child’s learning and education) and scaffolding a child’s decision-making and future planning capabilities. A meta-analysis conducted by Hill and Tyson (2009) found that academic socialisation had the strongest positive association with student achievement compared to the other two components of parent engagement. While most research focusses on parent engagement during the primary school years, its positive effect on student achievement continues during adolescence (Hill & Tyson, 2009; Hill & Wang, 2015; Hill et al., 2018; Gordon, 2016; Gordon & Cui, 2012; Wilder, 2014).

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage where physiological changes, changes in the school environment, and changes in relationships with peers and parents occur. These transitions may challenge adolescents’ sense of identity, and thus adolescence is a vulnerable period (Alsaker & Kroger, 2006). The impact of adolescent challenges on adult outcomes has only been recently noted (Due et al., 2011), with many scholars acknowledging adolescence as a ‘turning point’ where life trajectories may be especially malleable (Johnson et al., 2011), and where the impact of previous life stages may combine with adolescent experiences to influence outcomes in adulthood (Pollitt et al., 2005). While previous life stages influence identity formation, in adolescence, education and occupational goals are integral in shaping who adolescents are and would like to be (Flammer & Alsaker, 2006).

Adolescence is also where, for some students, we observe a decline in student engagement with education (Archambault et al., 2009; Fredricks & Eccles, 2002; Lam et al., 2016; Trautwein et al., 2006) and academic performance (Hill & Tyson, 2009). Many adolescents also experience declining self-concept (Nagy et al., 2010) and increased anxiety and depression (Merikangas et al., 2010; Paus et al., 2008; Twenge et al., 2019) linked to extensive physiological and psychosocial transformations and vulnerabilities (Blakemore, 2012; Casey et al., 2008). School (Verhoeven et al., 2019) and family (Beyers & Goossens, 2008; Schachter & Ventura, 2008) contexts play important roles in mitigating these challenges and shaping identity formation.

Key aspects of school context that matter for adolescent identity formation and academic and wellbeing outcomes include school belonging, peer connections and bullying (Gillen-O’Neel & Fuligni, 2013; Bond et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2015). School belonging is ‘the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment’ (Goodenow & Grady 1993, p. 80). Higher levels of school belonging are associated with lower levels of school-dropout (Gillen-O’Neel and Fuligni (2013). Peer connections at school are positively associated with lower rates of anxiety and depressive symptoms, drug use, and disruptive behaviour in adolescents (Bond et al., 2007) while, bullying or peer victimisation amongst school peers adversely impacts outcomes such as school completion and employment (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015; Moore et al., 2015).

Parenting styles play an important role in adolescence, bolstering psychological wellbeing and academic success. Parenting styles such as authoritative parenting (Baumrind, 2005) or autonomy-granting parenting (Darling & Toyokawa, 1997), that foster greater independence while setting and maintaining realistic discipline and rules, are related to adolescents’ positive self-evaluations and self-concept (Cripps & Zyromski, 2009) and lower depression (Yap et al., 2014). In contrast, parenting styles more focused on enforcing higher expectations, sometimes with punitive approaches with a lessened focus on independence, such as authoritarian or demanding parenting, are related to increased anxiety (Yap et al., 2014) and poorer school achievement (Pinquart, 2016). Finally, parenting styles that are sensitive to, and assist with, the emotional needs of adolescents—such as warm or responsive parenting—are related to lower anxiety and depression (Yap et al., 2014).

Despite the positive benefits of parents engaging in their child’s education, such as improved academic achievement and wellbeing, parent engagement in learning progressively declines during primary school (Cheung & Pomerantz, 2011; Shumow & Schmidt, 2014). This may be due to a growing emphasis on student autonomy as students progress in school, and also because parents may feel less able to support their child academically in secondary school (Jensen & Minke, 2017). Parent engagement declines substantially in secondary school and for some students may be non-existent (Daniel, 2015; Green et al., 2007; Napolitano, 2013; Seginer, 2006; Spera, 2005). These declines are steeper among families from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds (Bridgeland et al., 2008). However, parent engagement in adolescence is critical for educational success and long-term outcomes. Kim and Hill (2015) found mothers’ engagement in their child’s learning during secondary schooling to be more strongly associated with academic performance than parent engagement during primary school. A lack of parent engagement in their child’s learning and education during adolescence is also associated with poorer mental health outcomes in adulthood (Bakoula et al., 2009; Mensah & Hobcraft, 2008; Westerlund et al., 2015).

Notwithstanding the evidence on the positive effects of parent engagement, significant gaps in our knowledge remain. Most studies focus on early childhood or use cross-sectional designs that do not account for the high variability in both the child’s development and the parent-child relationship over time. Adolescents undergo many developmental changes and longitudinal methods better account for the within- and between-individual variability that this unpredictable and turbulent period brings. Very few studies also examine how parent engagement with their adolescent child’s education particularly in early and middle adolescence influences mental health, self-concept and educational aspirations or expectations. Further, most studies examining the role of parent engagement on student’s educational outcomes use samples from general populations. Very little research examines how parent engagement in learning can support students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Finally, almost no research examines parent engagement and aspirations of school students in late adolescence who are living in socio-economically disadvantaged circumstances with complex needs. In addition to experiencing a combination of economic hardship, housing instability, physical or mental health conditions, learning difficulties, and language difficulties, some of these young people experience domestic and family violence and may be living away from their nuclear families.

We use the ‘linked lives’ principle to explore each aspect of parenting and engagement in their adolescent’s education and dimensions of the school context to explore how adolescents draw upon their social environment to develop future aspirations and maintain their mental wellbeing. The chapter is in two parts. Part 1 uses a general population sample to examine parent engagement in early and middle adolescence drawing on analyses using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) K cohort sample. Part 2 explores the complexities of parent engagement in student learning in late adolescence and how this influences educational and occupational aspirations and the stressors for mental health among students from highly disadvantaged backgrounds. This section draws on data from qualitative interviews with senior secondary school students (grades 10–12) who experience social disadvantage across multiple dimensions, including housing instability, contact with the child protection system, contact with the youth justice system, early parenthood, learning disability, or being part of a cultural or linguistic minority. These interviews come from the Learning through COVID-19 study funded by the Paul Ramsay Foundation (McDaid et al., 2021). This approach allows us to extend generalizable findings about associations between parental engagement and student outcomes with new insights about how disadvantaged students experience parent engagement during remote learning and how this influences their aspirations and wellbeing.

Early and Middle Adolescence

In early and middle adolescence, adolescents are still strongly influenced by their family context, including parent engagement in their education and parenting styles. Adolescents are also affected by their school setting through peer connections, feelings of school belonging and bullying.

The Study

Using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) K cohort sample, we explore the associations of parent engagement in their child’s learning and education with ability self-concept, mental health, and educational aspirations. These analyses allow for an examination of parent engagement and key family and school factors across two time points in early and middle adolescence. The wave five data were collected in 2012 and 3956 adolescents aged 12–13 years took part in the study. The wave six data were collected in 2014 and 3537 adolescents aged 14–15 years took part in the study. Only adolescents who answered the relevant questions were included in the sample. Forty-one parents from wave five and 162 from wave six, did not give consent for their child to answer questions about stress, anxiety, and emotions and 9 adolescents from wave 5 and 24 from wave 6 chose not to answer these questions.

For our analyses examining parent factors, we use measures of parent engagement in their adolescent’s education and adolescents’ perceptions of their parenting styles. Combined parent engagement in their adolescents’ education is measured using the combination of adolescents’ ratings of their mothers’ and fathers’ interest in their education, rated from “no interest in [their education] at all” to “a lot of interest.” Parenting styles were rated by adolescents using the Parenting Style Inventory II (Darling & Toyokawa, 1997) and scale means of responsive parenting, demanding parenting, and autonomy-granting parenting were constructed.

To examine the school environment, we use measures of peer connection problems, experiences of bullying in the last month, and feelings of school membership. Peer connection problems—i.e., difficulty getting along with and connecting with peers—uses five items from the peer problems subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) and was reported by the adolescent themselves. Example items include “picked on/bullied by children” and “has been solitary”. Experiences of bullying in the last month was reported by the adolescent and constructed into a binary categorical variable of any experience of bullying, using six categorical questions asking about specific acts of bullying (e.g. “hit/kicked”, “threatened to take my things”, “said mean things/called me names”). School membership was measured using the Psychological Sense of School Membership (Goodenow, 1993) scale, comprising twelve items assessing adolescents’ experiences of peer and teacher relationships at school. Example items included “teachers are interested in me” and “other students accept my opinions” and adolescents rated how accurate each statement was to their experience at school.

Self-Concept

In adolescence thinking becomes more abstract, and self-reflection and self-awareness increase. Adolescence is potentially a time of self-concept difficulties, where one’s sense of self develops substantially (Sebastian et al., 2008). Adolescent development also includes adapting to or coping with new tasks including becoming more emotionally independent of parents and other adults, making plans and preparations for a future occupation, and developing values to guide behaviours (Seiffge-Krenke & Gelhaar, 2008).

While related to self-esteem and identity, the construct ‘self-concept’, measures ‘the perception of oneself, including one’s attitudes, knowledge, and feelings regarding abilities, appearance, and social relationships’ (Reynolds, 1993, p. 20). Self-concept is multidimensional meaning an individual can have ‘multiple interrelated self-concepts in a range of domains’ (Mercer, 2012, p. 11). For example, ability or academic self-concept is a broad domain that includes perceptions of abilities more generally as well as specific learning areas (e.g., reading, math, music). The effects of self-concept are stronger when specific to the learning domain, meaning that ability or academic self-concept may be different for the domains of mathematics and reading skills (Arens et al., 2011; Valentine et al., 2004).

To assess adolescent self-concept, we use a short-form measure of academic ability self-concept (Marsh, 1990), measured at waves five and six of LSAC. This measure comprised of three items about their academic ability at school and adolescents were asked to rate their agreement with each statement: “I learn things quickly in most school subjects”, “I’m good at most school subjects”, and “I do well in tests in most school subjects.” We used the scale mean to create a composite measure of academic ability self-concept, with higher values indicating more positive beliefs about academic ability.

Why Self-Concept Is Important for Student Outcomes

Numerous studies have found that self-concept in adolescence predicts higher levels of educational attainment (Guay et al., 2004; Valentine et al., 2004; Vargas et al., 2015; Wigfield et al., 2006) and academic achievement (Susperreguy et al., 2018). Eccles (1987) theorised that positive self-evaluations can foster children’s expectations of future success in academics. The ‘reciprocal effects’ model acknowledges that academic self-concept and achievement both affect each other, or are mutually reinforcing (Seaton et al., 2015). Positive academic self-concept has been found to predict educational attainment level 10 years later, while controlling for academic achievement, family structure and family socio-economic status (SES; Guay et al., 2004). A meta-review of longitudinal studies further demonstrated a significant, although small, effect size between positive self-belief and academic achievement when controlling for prior achievement (Valentine et al., 2004). This relationship was stronger when assessing self-belief within the academic domain, and when measures corresponded to this domain (e.g., by subject area) (Valentine et al., 2004). In addition to academic performance, academic self-concept also influences career related choices (Wigfield et al., 2006).

However, academic self-concept may be more likely to decline during adolescence than other domains of self-concept. Shapka and Keating (2005) measured the differences in domains of self-concept between grade 9 and grade 10, using the Harter Self-Perception Profile for College Students which measures general self-worth, and 12 sub-scales of self-perceived competence in various physical, social and cognitive domains. They found that most measures of self-concept increased with age, except for scholastic competence, which ‘declined over the course of high school’ (p. 88).

Parent Factors and Self-Concept

Given that adolescents typically experience a decrease in their academic self-concept, and that academic self-concept is linked to long-term educational attainment, it is important to consider what may act as a protective factor to maintain academic self-concept during adolescence. Parent engagement in education improves student perceptions of their self-worth and self-efficacy (Cripps & Zyromski, 2009). One pathway that may account for the positive effect of parent engagement on student outcomes is the effect of parent engagement on self-concept as self-concept is often framed with reference to parents and peers.

Examining various dimensions of self-concept, Cripps and Zyromski’s (2009) review found that parent involvement in their child’s education can positively or negatively affect adolescents’ self-concept depending on parenting style. Authoritative parenting led to more positive self-concept and higher levels of intrinsic motivation for learning (Cripps & Zyromski, 2009) than authoritarian and permissive parenting styles. In other words, parents who provided both structure and opportunity for independence fostered positive self-concept and greater internal motivation for learning. Similarly, in a study that examined the relationship between parental involvement, growth-fostering relationships, and self-concept in adolescents, perceived parental involvement significantly contributed to a positive self-concept (Gibson & Jefferson, 2006).

We utilise a panel fixed-effects regression model to account for the high variability in both the child’s development and the parent-child relationship over time when examining parent effects on adolescent academic ability self-concept. As shown in Fig. 6.1, several parental factors are significant predictors of academic ability self-concept. Firstly, parent interest in education—namely the parent engagement dimension relating to home-based engagement—had a positive association with student academic ability self-concept, even when accounting for other parenting, school, and sociodemographic factors. Turning to other parenting factors, responsive and autonomy-granting parenting were both associated with significant increases in positive academic ability self-concept. These findings resonate with past research which suggests that adolescents receiving greater engagement with their education from their parents and experiencing parenting styles that fosters greater self-reliance as well as providing positive feedback on academic performance (Cripps & Zyromski, 2009; Putnick et al., 2008) have more positive beliefs about their abilities.

Relationship between self-concept and factors in the family and school contexts

Notes: Coefficients from a panel fixed effects regression model adjusted for gender and Indigeneity. All black bars in the figure are statistically significant at p < 0.05 and grey bars are not statistically significant. (Source: The Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (Waves 5 and 6) sample (observations n = 6585) (individuals n = 3727))

In addition to psychosocial parenting factors, the findings also highlight how family composition can influence adolescent self-concept. Specifically, the results presented in Fig. 6.1 shows that living in a blended family is associated with a lower academic ability self-concept than living with two biological parents. Previous research with US adolescents has found that, after controlling for key demographics such as gender, race and socio-economic status, family structure is the strongest predictor of academic achievement (Jeynes, 2005). This is the strongest predictor in the model and suggests the influence of family structure extends to academic ability self-concept as well as academic achievement.

School Factors and Self-Concept

Self-concept has been theorised as a mechanism that explains the relationship between peer bullying and academic achievement, given its strong association with both academic outcomes and bullying (Roeleveld, 2011; Valentine et al., 2004). Cross-sectional research suggests that bullying victimisation influences academic achievement indirectly through academic self-concept for adolescent girls (Jenkins & Demaray, 2015). Furthermore, a meta-analysis examining the associations between self-concept and academic achievement found a small effect of positive self-belief on academic achievement that was stronger for self-beliefs specific to the academic domain (Valentine et al., 2004). Quality relationships with peers also exerts an important positive influence on adolescent’s general self-concept (Hay & Ashman, 2003). While there is scant research on the relationship between peer connections and academic ability self-concept, it seems plausible that positive peer connection would contribute to strengthened academic self-concept through positive environmental factors, such as social networks, in the school setting (Jenkins & Demaray, 2015). Finally, in terms of the overall social environment, collegial school contexts may facilitate positive self-beliefs about academic ability. Given that self-concept is influenced by social factors, such as social comparisons, sense of safety at school and teacher-student relationships, school belonging may also influence academic or ability self-concept. Indeed, one study found a moderate correlation between school belonging and academic self-concept (Singh et al., 2010).

Turning to our findings on school factors, as shown in Fig. 6.1, we found that students were more likely to have a poorer academic ability self-concept if they reported more peer connection problems. Unexpectedly, we also found that students who experienced bullying recently had better academic ability self-concept. That is, more positive beliefs about their abilities. This is contrary to findings which suggest that having a more positive self-concept is related to lower reports of peer victimisation (e.g., Jenkins & Demaray, 2012). It may be possible that those with higher academic ability self-concept are targets for bullying, and that is what is driving this result. Nonetheless, this finding warrants further investigation. Finally, increases in feelings of school belonging had a small but significant positive effect on academic ability self-concept.

Mental Health

Adolescent mental health is becoming a global concern, with adolescents having the highest prevalence of mental disorders of all age groups (American Psychological Association, 2018; Australian Government, 2020). The global prevalence of mental health disorders affecting adolescents is 10–20% (World Health Organisation, 2020). In Australia 14% of those aged between 12 and 17 suffer from mental disorders, including depression, anxiety, ADHD, and conduct disorder (Lawrence et al., 2015). The prevalence of anxiety disorders is the highest (7%), followed by ADHD (6%) and major depressive disorders (5%) (Lawrence et al., 2015).

Internationally, rates of internalising mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression are rising (Bor et al., 2014; Gunnell et al., 2018; Mojtabai et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019). For example, large and nationally representative studies of US adolescents have shown an increased rate of major depressive episode of those aged 12–17, from 9% in 2005 to 11% in 2014 and to 13% in 2017 (Mojtabai et al., 2016; Twenge et al., 2019). The actual prevalence of mental health disorders is likely to be higher still as most cases may go unnoticed, because adolescents are less likely to seek help or they or their parents may not know how to recognise symptoms (Kessler et al., 2007; Lawrence et al., 2015).

We examine adolescent mental health through experiences of depression and anxiety, measured at waves five and six of LSAC. To measure depression, we use the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1995) which comprise thirteen statements. Example statements include “I felt miserable or unhappy” and “I found it hard to think properly or concentrate.” Adolescents were asked to evaluate whether each statement was “not true”, “sometimes” true, or “true.” The items were summed to create a measure of depression. For anxiety, we use the short-form Spence Anxiety Scale (Spence, 1998), comprising eight items. Example items include “I worry about things” and “I wake up feeling scared.” These statements were evaluated by adolescents on a scale from “never” to “always”. All items were summed to create a composite measure of anxiety.

Why Mental Health Is Important for Student Outcomes

The impacts of anxiety and depression on adolescent outcomes across the life course are numerous and include low academic achievement, increased risk of dropping out of school, increased risk of anti-social behaviour and diminished employment prospects (Bernal-Morales et al., 2015; Hatch et al., 2007; OECD, 2013). Leaving school before graduating is associated with precarious employment and a reduction in lifetime earning capacity (Lamb & Huo, 2017). A 25-year longitudinal study of New Zealand children found that the impact of poor mental health in adolescence persisted over the life course and was associated with higher rates of welfare dependence and unemployment (Fergusson et al., 2007). Mental health disorders also put individuals at greater risk of intentional self-harm and suicide (Daraganova, 2017; Skegg, 2005). According to the WHO, suicide is the third leading cause of death in adolescents aged 15–19 years old (World Health Organization, 2020). In Australia over the period 2017–2019, suicide accounted for 37% of all deaths among young people aged 15–24 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2021a).

Parent Factors and Mental Health

Numerous studies report that parent engagement in children’s education is a protective factor in reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Kang et al., 2017; Kim, 2016; Madjar et al., 2018; Piña-Watson et al., 2014; Tammariello et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019) and improving adolescent socioemotional functioning (Garbacz et al., 2018). However, few studies have shown how parent engagement in their child’s education can improve emotional functioning, for example decreasing anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescence (Bireda & Pillay, 2017; Matos et al., 2006; Tammariello et al., 2012; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014; Wang et al., 2019; Westerlund et al., 2015).

We used panel fixed-effects regressions to account for the high variability in both the child’s development and the parent-child relationship over time to examine parent factors and adolescent mental health. For depression in adolescents, we see that parent engagement in their child’s education decreases depressive symptoms in adolescence even when accounting for other factors such as school environment and sociodemographic characteristics (see Fig. 6.2). When examining parent factors for anxiety, parent engagement in their child’s education decreases anxiety symptoms in adolescence. However, when school factors like school belonging and experiences of bullying are taken into account (as shown in Fig. 6.3), parent engagement in their child’s education is no longer statistically significant.

Relationship between depressive symptoms and factors in the family and school contexts

Notes: Coefficients from a panel fixed effects regression model adjusted for gender and Indigeneity. All black bars in the figure are statistically significant at p < 0.05 and grey bars are not statistically significant. (Source: The Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (Waves 5 and 6) sample (observations n = 6585) (individuals n = 3727))

Relationship between anxiety symptoms and factors in the family and school contexts

Notes: Coefficients from a panel fixed effects regression model adjusted for gender and Indigeneity. All black bars in the figure are statistically significant at p < 0.05 and grey bars are not statistically significant. (Source: The Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (Waves 5 and 6) sample (observations n = 6585) (individuals n = 3727))

Parenting styles are also significantly associated with adolescent mental health. Adolescents who reported more responsive parenting also reported lower depression (Fig. 6.2) and anxiety (Fig. 6.3). While depressive symptoms were impacted by parental interest in an adolescents’ education, the key parental factor for decreased anxiety was a more general parenting approach that responds more actively towards emotional needs. These findings partially resonate with meta-analyses on parenting styles and adolescent mental health, particularly for warm parenting. Adolescents who report a positive relationship with their parents and where their parents are engaged in their lives, report lower anxiety and depression, with these benefits to mental health extending into young adulthood (Clayborne et al. 2021; Gorostiaga et al., 2019; Yap et al., 2014). However, although previous studies found relatively consistent associations between autonomy-granting parenting and youth depression and anxiety, we did not find a similar association in this study. Given that depression and anxiety are primarily mood-based health factors, responsiveness to emotional needs may have an immediate restorative impact on mental health, as compared to parenting that fosters greater independence.

School Factors and Mental Health

In terms of school factors such as diminished peer connections, past research has found peer conflict, particularly bullying victimisation, leads to both higher depression and anxiety (Halliday et al., 2021; Hawker & Boulton, 2000; Moore et al., 2017). In contrast, good peer connectedness, such as feelings of belongingness with ones’ school, can be associated with improved mental health amongst adolescents. Adolescence is a developmental period marked by transitions away from relying on adults toward peers (Fuhrman & Buhrmester, 1992)—such as classmates—for social support and esteem (McLaughlin & Clarke, 2010). Indeed, a systematic review of longitudinal studies of the impact of school factors on the emotional health of adolescents found that school connectedness was associated with a lower risk of depression for adolescents, regardless of gender, and anxiety for girls (Kidger et al., 2012).

In our models for adolescent depression (see Fig. 6.2) and anxiety (see Fig. 6.3), consistent with past research, adolescents with greater difficulty connecting with peers had higher depression and anxiety. Adolescents who reported recent experiences of bullying had higher anxiety (see Fig. 6.3) but bullying victimisation was not associated with changes in depression (see Fig. 6.2). Regardless, depression is nonetheless linked to difficulty with connecting with peers, highlighting the importance of positive peer relationships in adolescence for mental health outcomes. Indeed, adolescents who experienced increased feelings of school connectedness also reported lower depression (see Fig. 6.2) and anxiety (see Fig. 6.3). In other words, as adolescents progress through secondary school and become more integrated in the wider student body, these social networks subsequently provide benefits to their mental health.

In sum, adolescent mental health is impacted simultaneously by a multitude of social relationships across two central domains: parental factors and school factors. Parental engagement in their child’s education can communicate commitment in an adolescent’s future, leading to direct decreases in depression even when accounting for important school factors. In addition, as adolescents expand their available social resources for support, their mental health still benefits from parenting that is responsive to their emotional needs. School factors such as experiencing conflict with peers are associated with increased depression and anxiety. This may be mitigated by widening social circles, particularly at school, which also provides an avenue through which youth can access social support. Adolescents who report greater belongingness to their student body see improvements in their mental health as they progress through secondary school education.

Educational Aspirations

Adolescence is often the time young people start to consider major future goals. A key decision is whether to continue on to further education or to enter the workforce. Across OECD countries, about half of young people transition out of the education system, with the majority of these individuals entering employment (OECD, 2020). Of those who continue onto further education, most will pursue a tertiary qualification, but others may choose another form of post-secondary non-tertiary option. In Australia, 81% of school leavers completed some form of secondary-level education with 60% enrolled in a form of further study (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Of our sample from the K cohort in LSAC, approximately 71% anticipate seeking a university degree, with 14% seeking to enter trade or vocational training and 15% not considering further education.

Educational aspirations was measured at wave six of LSAC using a re-coded categorical variable where adolescents were asked “Looking ahead how far do you think you will go with your education?” with the categories “complete secondary school” (reference group), “complete a trade or vocational training course”, or “complete a university degree.” Adolescents also responded to a binary question where they indicated if they discussed their futures with their parents. This measure was used as a component of academic socialisation.

Why Educational Aspirations Are Important for Student Outcomes

A wealth of evidence suggests that high educational and career aspirations during adolescence leads to increased educational attainment (Beal & Crockett, 2010; Rojewski, 1999), occupational prestige, and wage attainment in adulthood (Pinquart et al., 2003; Schoon & Parsons, 2002). Furthermore, OECD data suggests that completing post-secondary education, particularly at a tertiary level, is related to higher employment rates, wages, and wage growth later in life (OECD, 2020). These trends highlight the need to understand the motivations and contributing factors to adolescent aspirations for the future, especially as adolescence is a period in which young people develop meaningful understandings of education and future-oriented goals (Anders & Micklewright, 2013; Croll & Attwood, 2013). These educational and occupational goals not only shape who they would like to be, these educational plans have long-term consequences for later life outcomes.

Parent Factors and Educational Aspirations

Parents can play a substantial role in shaping adolescents’ goals for the future. Parenting styles that focus on imposing high expectations on children may lead to increased stress in adolescents, and in turn poorer academic achievement. Alternatively, parenting styles that foster greater independence and trust may be associated with better academic achievement. Indeed, according to a meta-analysis, autonomy-granting and warm parenting was associated with greater academic performance over time (Pinquart, 2016). In contrast, this meta-analysis also found that more controlling or demanding parenting styles were associated with poorer achievement in school.

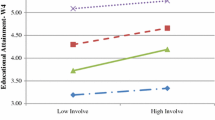

We used a multinomial logistic regression to assess how parent factors influence educational aspirations (see Fig. 6.4). When accounting for schooling and education-specific parenting factors, experiencing more demanding parenting was the only significant parenting style related to aspiring to attend university (Fig. 6.4). In other words, experiencing high expectations from parents, rather than receiving more independence fostering and emotionally responsive parenting, is a driver of pursuing higher education.

Relative risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals of factors in the family and school contexts for adolescents aspiring to pursue tertiary education. (Reference group: Only complete secondary school)

Notes: Relative risk ratios from a multinomial logistic regression model. All black bars in the figure are statistically significant at p < 0.05 and grey bars are not statistically significant. (Source: The Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (Wave 6) sample (n = 2566))

In addition to general parenting styles, parents with higher educational attainment may be more engaged in their children’s education at home, likely because they have directly experienced the benefits of further education themselves (Tan et al., 2020). This increased engagement may be associated with adolescents’ educational expectations, and with being socialised towards a more education-oriented direction, an important factor related to student achievement (Hill & Tyson, 2009). Indeed, extant research has found that adolescents whose parents have higher expectations for their education may have more substantial future aspirations (Hill et al., 2004) and higher academic achievement (Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020; Strom & Boster, 2007). Given that greater academic achievement in secondary school also leads to improved economic outcomes in adulthood (Ashby & Schoon, 2010; Schoon & Parsons, 2002), parents thus play a critical role in the future economic outcomes of their children.

Parental interest in children’s learning can also take the form of direct interest in the education itself, such as children’s academic performance or school activities. This form of parental interest is associated with increased academic success in school (Pinquart, 2016; Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020). In contrast, academic outcomes including educational aspirations post-secondary school may be more influenced by more future-oriented parenting factors. Academic socialisation—the process through which parents foster greater understanding in the value of education, while providing helpful strategies for scholastic success as well as cultivating future plans with their children—is strongly related to academic achievement (Hill & Tyson, 2009; Hill & Wang, 2015; Hill et al., 2018; Gordon, 2016; Gordon & Cui, 2012; Wilder, 2014).

As shown in Fig. 6.4, in contrast to research examining academic achievement, parental interest in learning may not be as strong for influencing aspirations. Specifically, results suggest that parent interest in learning itself is not enough to encourage adolescents to aspire for higher education (see Fig. 6.4). However, our results suggest that academic socialisation, a more future-oriented and values driven parenting factor, is related to higher odds of aspiring to pursue a university degree relative to only completing secondary school (see Fig. 6.4). Specifically, adolescents who report discussing their future plans with their parents have higher odds of aspiring to go to university relative to preferring to only complete secondary school. Together, these results suggest that general interest in an adolescents’ schooling is not enough to foster further educational aspirations. Instead, parent engagement through academic socialisation, specifically through active discussions about the future, is critical in promoting adolescents’ goals to pursue tertiary education. These results hold even when adjusting for living in the most disadvantaged regions.

Finally, it is important to consider that the relationship between discussing future plans with one’s parents and aspiring to go to university (compared to adolescents who have no plans for further education) may reflect having sufficient socio-economic resources that facilitate viewing university as a viable future option. Adolescents from low socio-economic status backgrounds may be averse to aspiring to further education due to the risk of significant downward mobility if they are unsuccessful in completing additional schooling (van de Werfhorst & Hoftstede, 2007). Families who are markedly disadvantaged also experience greater difficulty engaging with their children’s education (Baquedano-López et al., 2013). Contributing factors to this difficulty can range from the structure and culture of schools which better facilitate parental involvement for more advantaged families, to limited time and resources to contribute to their children’s school activities. Thus, another way of interpreting our results is that for adolescents not intending to pursue tertiary education, the role of academic socialisation may be less important in these families, as their resources to engage with their children’s education are far more limited. Despite the fact that pursuing further education leads to better economic outcomes in adulthood (Schoon & Parsons, 2002), familial socio-economic factors during adolescence may nonetheless limit the options that could be considered following secondary school, leading to persistent social disadvantage.

School Factors and Educational Aspirations

Peer problems during adolescence are correlated with poorer employment rates at young adulthood (Bania et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2015), highlighting the need to examine peer and school factors associated with adolescent educational aspirations. Disruptive school environments and greater peer conflict are related to students having more behavioural problems, disengagement from school, and lower educational aspirations (Metsäpelto et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2010). Additionally, having difficulties getting along with peers is related to lower odds of aspiring for full-time education post-secondary school relative to aspiring to enter full-time employment or vocational training (Hartas, 2016). Furthermore, adolescents who have experienced bullying have lower odds of considering completing a secondary school qualification as important (Hartas, 2016; Pinquart et al., 2003). In terms of positive peer and school factors, having a greater sense of school belonging may be associated with better school motivation (Gillen-O’Neel & Fuligni, 2013), having more positive future-orientations (Crespo et al., 2013), and a lower likelihood of not completing secondary school (Bond et al., 2007).

As seen in Fig. 6.4, the results from our multinomial logistic regression suggest that having a greater sense of school belongingness is related to higher odds of aspiring to go to university, relative to only seeking to complete secondary school. However, in contrast to past research, we did not find a significant relationship between experiences of peer disconnection or bullying victimisation with educational aspirations. Furthermore, although school belongingness is statistically significantly related to higher odds of aspiring to attend university relative to no further education aspirations, the effect size is also quite small, suggesting that parent influences may be more important for seeking to enter higher education.

Finally, turning to decisions to pursue further education through vocational study, parent and school factors were not significant correlates (see Fig. 6.5). Instead, the only significant correlate is gender, with girls having a lower odds of aspiring to trade and vocational study relative to boys when compared to having no aspirations for further study following school completion. Trade occupations remain male-dominated in Australian society (WGEA, 2019), suggesting that aspirations towards trades is based on gendered norms. In other words, parental and school factors may influence attitudes towards further education, however, entering the workforce following a non-tertiary education route post-secondary school was found to be only related to gender.

Relative risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals of factors in the family and school contexts for adolescents aspiring to complete trade or vocational study (Reference group: Only complete secondary school)

Notes: Relative risk ratios from a multinomial logistic regression model. All black bars in the figure are statistically significant at p < 0.05 and grey bars are not statistically significant. (Source: The Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (Wave 6) sample (n = 2566))

Together, these results suggest that parents, rather than peers or the school environment have the most impact on adolescent aspirations for pursuing tertiary education. This is in contrast to research that suggests that peers, rather than parents, have greater influence on adolescents engaging in risk behaviours (Dafoe et al., 2018). Interestingly, parent interest in education was not significantly correlated with post-secondary aspirations. Instead, higher parental expectations and the prioritisation of future goals emerged as important determinants of adolescent aspirations. Specifically, greater academic socialisation, through active discussion of plans for the future with parents, plays a critical role in developing future-oriented goals in adolescents such as aspiring to complete a university degree. Furthermore, receiving more demanding parenting from parents was also linked to aspiring to pursue higher education. Collectively, these results suggest that future-oriented parent engagement in the form of academic socialisation, rather than an immediate interest in a child’s school performance (such as school-based parent engagement), is essential for aspiring to pursue further education.

Late Adolescence

One important theme in late adolescence, from a life course perspective, is that of ‘continuity and discontinuity in life pathways’. Late adolescence is a time where individual development can either continue a stable trajectory across life stages or be redirected (Johnson et al., 2011, p. 273). Neither transition is objectively good or bad, but educational plans during late adolescence can have long term consequences for later life outcomes. Educational plans and aspirations can be impacted by familial context and parental-adolescent relationships (Whiston & Keller, 2004). Parenting can influence adolescents’ educational aspirations through socialisation of educational values (Spera, 2005), with children whose parents express higher educational aspirations for them, having higher academic and educational goals than children whose parents have lower educational aspirations (Sawitri et al., 2015).

The Study

In the second part of this chapter, we present new insights into the complexities of parent engagement in late adolescence for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. We also provide a brief overview of how these students perceived support from their parents with their mental health and finally, how they felt about the future and what aspirations they held.

We draw on data from a larger study (Learning through COVID-19 funded by the Paul Ramsay Foundation) consisting of qualitative interviews with 29 senior secondary school students (grades 10–12Footnote 1) from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds from three states in Australia. The interviews were undertaken between September and November 2020 and examined how COVID-19 lockdowns impacted student learning and educational support. Some students experienced high levels of socio-economic disadvantage across multiple dimensions, including housing instability (n = 5), contact with the child protection system (n = 6), contact with the youth justice system (n = 1) and parenting at least one child (n = 6). Nine students were part of a cultural or linguistic minority, and one student identified as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. All participants were recruited through service providers who were briefed to approach students living in socially disadvantaged circumstances who were struggling at school and at risk of disengaging.

The participants were predominantly female (6 male/23 female) and lived with at least one parent (n = 19). One third (n = 10) lived either independently, with extended kinship, in refuges or in residential care, having little or no contact with their parents. The sample composition provided analytical leverage for exploring parent engagement beyond the nuclear family offering potential to further conceptualise what parent engagement entails for students in late adolescence. Some participants were enrolled in mainstream (n = 13) and others in flexi-schools (n = 16). Flexi-schools are an alternative option to mainstream schooling in Australia for students, often from disadvantaged backgrounds, who have struggled with the mainstream schooling system. They come in various forms—some are attached to a mainstream school, while others are completely separate institutions. They are generally characterised by the provision of extra support to help students with their life outside of the classroom (such as counselling or housing support) as well as flexible ways of learning, smaller class sizes and increased access to teachers.

What Does Parent Engagement in Learning Look Like in Late Adolescence in Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Households During Remote Learning?

Parent engagement in student learning decreases as students move up year levels (Daniel, 2015; Murray et al., 2015). Given the increasing expectations placed on maturing students, it is to be expected that this trend is further exacerbated in secondary school. The experiences of the participants in this study illustrate this tendency from their perspective, for example, feeling less supported compared with younger siblings:

Participant: My parents […] don’t really care as much because I’m older. I don’t know.

Interviewer: So, when you compare with your younger brothers, did you feel that they were getting more from your parents to help them out?

Participant: Well probably, because, I don’t know, they need more, I don’t know, attention and learning and everything. Because I already know most things. (#3, female, 18, grade 12)

However, older participants did not necessarily feel they were being overlooked or missing out unfairly. There was a shared understanding that greater academic capacity also justified taking on more responsibilities for keeping up with schoolwork. This understanding is potentially problematic if secondary students see themselves being less able to ask for help when needed, or if support is reductively thought about as ‘assistance with homework’. Indeed, many participants with younger siblings took on responsibilities for supporting their siblings’ learning as well as their own. This was particularly pronounced for participants from a CALD background.

I help my mum raising all of the children, helping out with the cares and also helping the – my younger siblings with homework and things like that. (#18, female, 17, grade 11)

Students from a CALD background were also less likely to draw on their parents for support, due to language barriers or subject knowledge, as explained by this student:

My mum doesn’t understand English, my dad’s [and] my brothers, their English is really, really poor, and my oldest brother, I did ask him for my maths help, but he’s terrible at his maths. (#20, female, 17, grade 11)

This left a gap not easily filled by overworked teachers. This student went on to explain:

They [my teachers] said, ‘Is there any people who could help you with your English?’ Yeah, and I respond, ‘There is nobody.’ Because I live with my mum and dad and I have an older brother and the others are young. They go to primary school, and my youngest brother is age four. Yeah, so this was really hard. (#20, female, 17, grade 11)

In circumstances where parents were available to engage in their children’s learning, mostly at home, participants expressed their appreciation and the positive impact this had on them.

I only live with my mum. I don’t have much to do with my dad […] she was really helpful […] especially because she was doing a lot of things online too, so we could kind of both help each other to stay motivated. And she was a big help in just making sure I was staying on track. She would best try to explain the different things. She’s a primary school teacher, so she couldn’t help as much as my high school teachers would, of course. But she could still try and explain things to me the best she could and, yeah, she was a big, big help. (#29, female, 17, grade 11)

In this excerpt, help is framed as mutual within the parent-adolescent relationship, rather than positioning the participant as a passive recipient of educational support from an adult. Parent engagement needs to account for competence and autonomy within the way that it is implemented (Li et al., 2020; Raftery et al., 2012). These excerpts also illustrate the need to engage with parent engagement practices in contexts where students have limited contact or no parents at all in their lives.

What Does Parent Engagement Look Like in Non-traditional Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Households During Remote Learning?

Ten participants in this study were living independently, had limited or no contact with their nuclear family, or had living arrangements with extended kinship members. Not all adolescents have a connection with their biological parents. According to the Child Protection National Minimum Data Set, at 30 June 2020, 7286 adolescents aged 15–17 were living in out of home care in all of Australia (8.3 per 1000 children). For the states included in our sample, NSW had the highest rate of adolescents aged 15–17 in out of home care (10.7 per 1000 children), followed by Tasmania (8.6 per 1000 children) and Queensland (6.5 per 1000 children) (AIHW, 2021b). This is an important opportunity to gain a better understanding of how adolescents whose experiences do not fit neatly into narrow definitions of parental engagement have their support needs met by drawing on different available sources to enhance their educational engagement. Here, who provides support for learning is less important than the timely access to and level of trust developed in relations with school staff, social workers, service providers or other members of the community. In particular, flexi-school students commented extensively on having access to these sources of support, including crucial emotional support:

I was just sitting in class and [school staff member] just came up and he just put a glass of water and goes, ‘If you need to come and have a chat, just come and chat whenever you need.’ It was just good knowing that they could see that I was upset. I didn’t have to say I was upset, they could just see it, and then they just knew just to not push me. […] It is pretty stressful, but it’s good to know that I am able to do some at home and that if I need help, that I am able just to talk to [school staff member …] even after school hours […] because they know how important this job is to me, and they know how important my Year 10 is to me, and they know how much stressed I am. I feel I could just explode. (#39, female, 16, grade 10)

This experience indicates how needs for social, educational, and emotional support overlap and bear upon educational and occupational aspirations and possibilities. This student was living independently with her partner and his grandmother, after having spent some time homeless and in a refuge. She had no contact with her family of origin and at the time of the interview, was juggling schoolwork with a work placement which she hoped would lead into a career after completing secondary school. She also struggled with anxiety, and the wraparound support provided by the school was crucial for meeting needs that would in other circumstances be covered within the nuclear family.

In the absence of parent caregivers, students turned to the relationships with their school or others in their families. Further strategies to enhance participants’ capacity during remote learning included meeting basic needs for personal space, food, and drink as well as safety. For the participant below and her siblings, while their mother was working, this support was provided by:

My grandma […]. Checking up on us, if we needed anything, like waters, drinks, food while we were working […]. As much as she could. (#2, female, 15, grade unspecified)

Extended kinship support was also significant for academic socialisation, as described by this participant:

My aunty […] I was living with her when my grandma passed away, but then I decided to move out and do my own thing. […] She’s going to help me finish school and then she’s going to try and help me get into TAFE and probably do a few more courses and TAFE and then, yeah, look for a job then. (#21, female, 18, grade unspecified)

This student faced many barriers progressing through school and on to TAFE – she had a young child, had been in the Child Safety system and suffered with multiple mental health disorders. Child Safety played a role in forcing her to attend school again, which she spoke of with resentment, but it was the support of her family member that had helped her to plan for, and have expectations of, a sustainable future.

The temporary involvement of a parent, even when that involvement occurred amidst changing home environments, was helpful for one of the adolescents interviewed in this study. He resided in a youth housing facility, had significant mental health concerns and was in contact with the Child Safety and Justice systems. During some of the time that COVID-19 lockdowns were in place, he lived with his mother, and spoke of her assistance with grateful appreciation:

Interviewer: And you said that your mum helped you. How did – how did she help you during that time?

Participant: She was just reading the questions out for me, like the ones I couldn’t read. Yeah, like sort of like helping me, like she was doing the sounds and like trying to […] break it down into like two […] and then try to put it together yourself? […] Well, that’s what mum was doing.

Interviewer: And had she ever helped you before or was it just during COVID […]?

Participant: It was just during COVID […] Like, she didn’t have to, you know.

(#38, male, 17, grade 10)

Even though this participant was receiving support from the education and Child Safety systems, the temporary engagement of his biological mother in his learning was meaningful to him. The range of sources and practices of support for student engagement in learning during COVID-19 lockdowns highlights how context matters for secondary school students’ educational experiences. Practices included multiple stakeholders and caregivers, temporary or more sustained engagement that often extended beyond simply offering home-work assistance, for example, liaising with school and other partners in the educational system in addition to providing a supportive home environment in which learning takes place.

How Does Parent Engagement in Learning Contribute to or Mitigate School Related Stress During Remote Learning in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Households?

Our qualitative interviews also highlighted some complexities in relationships between parental engagement and student mental health and wellbeing. As this student from a CALD background shared:

Participant: My parents, they don’t speak English, they were like, ‘[…] you can do it. You can do this.’ And I’m thinking, ‘They haven’t been in my position.’ I’m like, ‘Mum, you don’t know even how to do this. Why are you saying it’s easy to do it?’[…] it’s like they want me to do something. […] Most of [ethnic] families want you to be a doctor. They don’t know how hard is […]

Interviewer: Did you feel like that added more stress?

Participant: Yes, I did. Because there was the teachers, us, big pressure. They’re teaching us on this time, and they were like my family, they think I could do it. I was trying to make them happy, like actually doing my work […]. The family loves you, they think you can do it, and so you don’t want to put them down. You don’t want to make them wrong that you can’t do it. (#20, female, 17, grade 11)

This students’ parents offered (well-meaning) encouragement to persist with difficult tasks while learning from home during COVID-19 restrictions. However, their daughter perceived this as misaligned with her lived experience and interpreted it as a lack of family capacity to empathize with her. This was compounded by her parents’ desire for her to follow a specific occupational pathway which required a high level of academic success in secondary school. Parent (and teacher) engagement generated undue pressure and feelings of isolation, triggering anxieties around disappointing those who had expressed a belief in this student’s abilities. In this way, the responsibility to perform well was felt even more acutely. In contrast, we also saw the potential for parent engagement to mitigate performance pressure when attuned to the secondary school students’ experiences. These students below reflected on learning during COVID-19 and the role of their parent:

It was definitely a constant stress. It felt like school was never ending. Especially for me, I’m quite a perfectionist when it comes to it. So no matter what I do, I can’t go, ‘Oh well, that’s good enough.’ I feel like it has to be the absolute best I can do. So that’s why I would sit there for hours and hours trying to do it when I really just couldn’t. My mum’s actually a teacher, and she just doesn’t think that homework is very beneficial. So, she would kind of see how much I was struggling. (#29, female, 17, grade 11)

I know from my dad, he was like really supportive about it, like telling me not to stress, like just try and do as much as I can. (#1, female, 15, grade unspecified).

Parents like these engaged in their children’s learning as much through encouragement to persist as they did in encouragement to take time out. Some participants mentioned support from parents and other caregivers in pacing themselves, taking regular breaks and moderating (unrealistic) expectations. Some participants who were enrolled in flexi-schools commented that their parents’ ability to identify when they were not thriving in the mainstream system, and support them in enrolling in alternative school models, was a significant factor in their continued educational participation and had resulted in improvements in their mental health.

What Were the Educational Aspirations and Expectations of Senior Students from Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Households During Remote Learning?

During late adolescence exploring possible future life plans such as studying further or preparing for a job or career is an important task in the development of identity. These choices shape life course trajectories and may be a source of stress, given that the stakes are perceived as high. Decisions for an educational or occupational pathway often have consequences for many years to come, incur financial and other costs, and may require commitments from immediate family or caregivers for their successful implementation. Such decisions are based on pragmatic constraints (i.e., the resources available to the student and their family) and individual aspirations (i.e., the disposition to pursue an educational or occupational goal over another). We define aspirations as future orientation, planning for a career or educational pathway. Aspirations here are considered separately from expectations, with the former referring to what the individual would like to do in the future, and the latter to what they expect they will do (Almroth et al., 2018). Aspirations are sensitive to socio-economic status (Goldthorpe, 1996; Coates, 2014) with students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds having lower aspirations for educational attainment than students from more advantaged backgrounds.

All adolescents in our sample planned to complete year 12, with most intending to go on to further study at TAFE or university. This was quite remarkable, given the significant level of disadvantage these students were experiencing in their lives. Some expressed their future plans in terms of expectations rather than aspirations, particularly those who were uncertain of what they wished to do but expected to go on to TAFE and hopefully discover an occupational pathway.

I’m thinking of getting a job and then like getting myself into a TAFE course. (#24, female, 16, grade 11).

Participants rarely framed their discussion of aspirations and expectations in terms of support received from their teachers or parents. This may reflect the desire for independence and autonomy that characterises adolescence, although participants also struggled with the responsibilities, they perceived that the next stage of their life would bring. Discussions about educational and occupational futures revealed that for many participants these were areas of considerable uncertainty and, in some cases, worry:

Quite a big worry has been that […] I’m not going to be quite […] smart enough to go to uni or become an adult. I guess that’s quite scary to me, having responsibilities. That’s quite terrifying. […] I only have basically one year left and then I’ll be 18. Just even leaving school is kind of scary to me because everything that I’ve known my whole life it’s going to change. I’ve got to start looking for jobs […] What scares me is kind of just being stuck. That’s something for me, which is really big, is that, yeah, I don’t want to ever feel trapped. What’s scary to me is that I’ll go into a job and maybe I realise that it’s not what I want to do and then I feel like that’s it (#29, female, 17, grade 11)

This excerpt indicates that some participants’ anxieties were fuelled by an understanding of their current life stage as one in which decisions now would be difficult to change later on. There is a sense of being expected to take responsibility accompanied by doubts about being ready for this degree of autonomy. Autonomy here was not longed for as a means of self-actualisation but contrasted with concerns about affordances (e.g., for experimentation or making mistakes) extended to young people in school becoming unavailable once secondary education was completed. These dynamics coincided with pressures to perform well in high stakes’ exams that would influence options for future educational and occupational choices. Participants commented on how conflicting pressures affected other activities they would usually engage in to cope with stress or just feel good:

Sports have been reduced a lot and because I’ve been more focused on my studies, I haven’t been able to […] spend that quality time with them [family and peers] lately […] at school, I’m doing four pre-tertiary subjects and that’s quite hard to manage because I’m trying to get … good grades in all of them and that’s—towards this time when […] exam time is getting really tough and […] it’s quite a large workload for me. (#19, male, 17, grade 11)

It is not surprising that adolescence presents an array of emergent pressures. Parents, family, peers, and school staff are the primary sources of support during this period. At the same time, the demands and emphasis on autonomy in adolescence change how support can be made available further challenging the way parents engage in their children’s learning. High aspirations in early adolescence have been linked to improved mental health (Almroth et al., 2018), so it is possible that despite these emergent stressors, students’ high aspirations will be a protective factor for their mental health, possibly through increasing positive attitudes towards their future life goals.

Conclusion

The convergence of developmental and contextual transitions in adolescence increases the risk for poor outcomes across the life course. It is therefore imperative to identify sources of support in home and school environments that can mitigate risks. Parents from disadvantaged backgrounds are at greater risk of experiencing barriers to both forming partnerships with schools and engaging in their child’s learning more generally (Fox & Olsen, 2014; Kim, 2009; Turney & Kao, 2009), therefore interventions targeted at these families and the support systems they draw on are needed to break the cycles of deep and persistent disadvantage.

Our chapter investigated the role of parent engagement during early, middle, and late adolescence on student outcomes and experiences. Findings from Part 1 show that parental interest in education was related to more positive academic or ability related self-concept, after controlling for family and school factors, although the effect was small. It was also related to lower levels of depression symptoms, although not anxiety after controlling for school factors such as bullying and school belonging. Parental factors, such as academic socialisation through parents discussing adolescents’ futures with them, and perceiving high parental expectations, were predictive of tertiary study aspirations. In contrast, general parental interest in their education was not related to adolescents aspiring for higher education. These results help to illustrate that parent engagement is important in early and middle adolescence, even when accounting for family and school context factors. However, it is also important to remember that the parent engagement or academic socialisation an adolescent receives may be contingent on socio-economic factors. While parent engagement can drive motivation towards higher education—an important facilitator of improved economic outcomes in adulthood—families must have resources to provide this form of engagement.

The findings from Part 2 build on those from Part 1 by allowing us to analyse parent-student engagement for students from highly disadvantaged backgrounds. The findings indicate that being attuned to adolescents’ shifting priorities, experiences and support needs is key. Engagement and support can be provided by parents, but also by significant others such as teachers, service providers, or community members. This engagement in their learning and support is perceived as important by these students. This may be especially true for students who are experiencing social disadvantage, and for whom continued involvement in education may strongly influence their outcomes in later life.

Notes

- 1.

For some participants, exact grade information was not available, however they were all aged 15 or above and this cohort specifically targeted adolescents in grades 10–12.

References

Almroth, M. C., László, K. D., Kosidou, K., & Galanti, M. R. (2018). Association between adolescents’ academic aspirations and expectations and mental health: A one-year follow-up study. European Journal of Public Health, 28(3), 504–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky025

Alsaker, F. D., & Kroger, J. (2006). Self-concept, self-esteem and identity. In S. Jackson & L. Goossens (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent development (pp. 90–113). Psychology Press.

American Psychological Association. (2018). Stress in America: Generation Z. Stress in America™ survey. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2018/stress-gen-z.pdf

Anders, J., & Micklewright, J. (2013). Teenager’s expectations of applying to university: How do they change? (Working Paper No. 13(13)). Institute for Education, Department of Quantitative Social Science.

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., Pickles, A., Winder, F., & Silver, D. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5, 237–249.

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. (2009). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in school: Relationship to dropout. The Journal of School Health, 79, 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00428.x

Arens, A. K., Yeung, A. S., Craven, R. G., & Hasselhorn, M. (2011). The twofold multidimensionality of academic self-concept: Domain specificity and separation between competence and affect components. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 970–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025047

Ashby, J. S., & Schoon, I. (2010). Career success: The role of teenage career aspirations, ambition value and gender in predicting adult social status and earnings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 350–360.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020). https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education-and-work-australia/latest-release. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

Australian Government. (2020). Productivity Commission 2020, mental health (Report No. 95). Canberra.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW]. (2021a). Deaths in Australia. Cat. no. PHE 229. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 25 June 2021, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths-in-australia

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW]. (2021b). Child protection Australia 2019–20. Cat. no. CWS 78. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 18 May 2021, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/young-people

Bakoula, C., Kolaitis, G., Veltsista, A., Gika, A., & Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Parental stress affects the emotions and behaviour of children up to adolescence: A Greek prospective, longitudinal study. Stress, 12(6), 486–498.

Bania, E. V., Eckhoff, C., & Kvernmo, S. (2019). Not engaged in education, employment or training (NEET) in an Arctic sociocultural context: The NAAHS cohort study. BMJ Open, 9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023705

Baquedano-López, P., Alexander, R. A., & Hernandez., S. J. (2013). Equity issues in parental and community involvement in schools: What teacher educators need to know. Review of Research in Education, 37(1), 149–182. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X12459718

Baumrind, D. (2005). Patterns of parental authority and adolescent autonomy. New Directions for Child Adolescent Development, 108, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.128

Beal, S. J., & Crockett, L. J. (2010). Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 258–265.

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., & Sadler, S. (2016). Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: The roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(6), 1053–1064.

Bernal-Morales, B., Rodríguez-Landa, J. F., & Pulido-Criollo, F. (2015). Impact of anxiety and depression symptoms on scholar performance in high school and university students, a fresh look at anxiety disorders. IntechOpen. Retrieved from https://www.intechopen.com/books/a-fresh-look-at-anxiety-disorders/impact-of-anxiety-anddepression-symptoms-on-scholar-performance-in-high-school-and-university-stude

Beyers, W., & Goosens, L. (2008). Dynamics of perceived parenting and identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 165–184.

Bireda, A. D., & Pillay, J. (2017). Perceived parental involvement and well-being among Ethiopian adolescents. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(3), 256–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2017.1321852

Blakemore, S. J. (2012). Imaging brain development: The adolescent brain. NeuroImage, 61, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.080

Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., & Patton, G. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), 357.e9–357.e3.57E18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013